Abstract

The LX tight gas reservoir displays significant heterogeneity, with a lack of alignment between engineering treatment and geological evaluation, leading to an unsatisfactory development outcome. Focusing on the Shihezi Formation of LX, a new comprehensive evaluation method is proposed for identifying sweet spots, taking into consideration both geological and engineering factors. The objective function utilized is post-frac production, and the grey correlation method was employed to quantitatively characterize the weight coefficients of geological and engineering parameters. The dual sweet spots index F was obtained through a normalized process. Utilizing the Petrel integrated exploration and development platform, the dual sweet spots index was incorporated into the geological model using coarse-interpolation. Subsequently, a dual sweet spots evaluation model was established to enhance the overall assessment process. The findings indicate the following: (1) There is a strong correlation between open flow production and the F-value, and the model’s predicted value closely aligns with the actual value. (2) A section with an F-value greater than 0.5 is identified as the optimal sweet spot, prioritizing development in this area. Sections with F-values within the range of 0.3 to 0.5 may be considered for fracturing but are not the primary choice. Sections with an F-value below 0.3 are deemed inefficient areas. (3) Based on the dual sweet spots evaluation model, it is recommended to focus on single layers He2, He5, and He6 in the LX area due to their superior quality compared to other layers. The research results offer crucial technical support for assessing fracability in this region, and hold significant importance for the selection of fracturing wells and the optimization of frac design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Being an unconventional oil and gas resource, tight gas is currently one of the most promising fields due to its extensive distribution range and abundant reserves. However, due to its complex geological environment, poor reservoir physical properties, and challenging development1,2,3, the horizontal well staged fracturing technology is generally adopted. This approach focuses on identifying the reservoir sweet spot as the primary basis for well location deployment and optimizing reservoir fracturing staging and perforation locations. It encompasses both geological.

Currently, there is a lack of a precise definition for fracability, fracability, and fracturing behavior in unconventional oil and gas reservoirs. In the early stages, the industry did not make a clear distinction between rock brittleness and fracability, often relying on the brittleness index to characterize the challenges associated with creating complex fractures4. At present, five primary methods for evaluating rock brittleness have been developed, including mineral content, elastic parameters, stress–strain curve, fractal statistics, and fracture energy5,6,7). Based on this foundation8, has developed a comprehensive fracability evaluation model that takes into account geological formations and rock brittleness. Reference9 introduced natural weak surface characteristics and proposed a fracability evaluation method that takes into consideration the brittleness of rocks and minerals, mechanical brittleness, and natural weak surface characteristics. Reference10 proposed an energy brittleness index to comprehensively evaluate the fracability of tight sandstone. Reference11 investigated the induced effect of fracturing and introduced construction parameters to establish an evaluation model. Reference12 developed a brittleness index evaluation method that comprehensively reflects the mechanical characteristics of pre-peak deformation and post-peak damage stages of rocks. This method takes into account the changes in various properties and energy during the process from plastic deformation to brittle fracture. Reference13 utilized machine learning to predict Young’s modulus and integrated it with fracture modeling to assess fracability. Reference14 introduced the hydraulic fracturing induction coefficient to accurately reflect the impact of stimulation displacement, reservoir seepage, fluid viscosity, horizontal principal stress difference, and other relevant parameters on fracturing performance. This approach effectively couples rock brittleness, fracture toughness, and the hydraulic fracturing induction coefficient to establish a comprehensive fracability evaluation method. Reference15 introduced tensile strength factors, in combination with fracture toughness and horizontal stress difference coefficients, to characterize the complexity of forming fracture networks after reservoir fracturing. Furthermore, an analytic hierarchy process was utilized to establish a frac evaluation model for offshore low permeability sandstone reservoirs. Reference16 studied the accumulation mechanism in the LX area. And the primary controlling factors influencing gas production in this area had been summarized. The relationship between the fracability and the final production were closely related.

Most of the fracture evaluation models and methods mentioned above are primarily focused on the single well scale. However, they do not fully account for the heterogeneity of three-dimensional reservoirs, nor do they adequately consider key geological factors such as natural fractures and crustal stress characteristics. Aiming to address the challenges posed by the strong heterogeneity of tight gas reservoirs, localized development of natural fractures, significant variations in in-situ stress characteristics across different regions, and the absence of a single effective reservoir prediction method in the LX block, we have developed a geological sweet spot prediction model. This model takes into account reservoir thickness, gas saturation, reservoir physical properties, and the degree of natural fracture development as the primary influencing factors. A multi-scale point-line (logging section) -body (seismic body) engineering sweet spot evaluation method is proposed based on the integration of core, logging, and seismic data. Additionally, a “geology-engineering” dual sweet spot evaluation method for tight sandstone reservoirs is established. Based on logging, core, and geological data, this method introduces a dual sweet spot evaluation approach that integrates geological and engineering perspectives. It derives a dual sweet spot index by employing a multi-factor analysis technique to assess the interactions among various factors. Subsequently, the accuracy of the model is validated through filed cases. According to the dual sweet spot index, it is possible to predict a well’s production and adjust the fracturing proposal based on these results. The model is capable of adjusting the corresponding coefficients for both geological and engineering sweet spots based on regional variations. This allows for the derivation of a dual sweet spot index that is tailored to local conditions, thereby ensuring alignment with the fundamental characteristics of the area. This provides theoretical support for predicting sweet spots and optimizing development schemes in the three-dimensional space of the entire research block.

Methodology

Geology-engineering dual sweet spots evaluation method

Due to the significant heterogeneity of LX tight gas reservoirs, the effectiveness of fracturing is influenced by a combination of factors including lithology, reservoir physical properties, ground stress, and degree of fracture development. Therefore, it is essential to consider both geological and engineering factors when developing a fracturing plan (Fig. 1). Based on the characteristics of the LX region, the parameters for identifying geological sweet spots primarily consider four factors: reservoir physical properties, gas saturation, reservoir thickness, and degree of fracture development. The engineering sweet spot index parameters mainly consider three aspects: brittleness index, horizontal stress difference and fracture toughness. We collected core data from 12 wells and conducted laboratory experiments to assess reservoir physical properties and rock mechanical characteristics. The results of these investigations are referred to as static parameters. Due to the limited core data, it is challenging to accurately represent the reservoir characteristics of the entire area solely based on the results from lab tests. Therefore, utilizing logging data from 82 wells (100 layers) in LX area, we calculated the reservoir physical properties and rock force parameters, collectively referred to as dynamic parameters. Since the static parameters are derived from experimental test results that exhibit high accuracy and reliability, the static parameters of an individual well are employed to adjust the dynamic parameters used in log calculations. This approach facilitates the establishment of a transformation relationship between dynamic and static parameters within the LX area. Ultimately, the results obtained from dynamic calculations are interpolated to derive the distribution of attribute parameters across the entire LX block.

Firstly, the optimized geological parameters of the desert and engineering parameters were standardized. Due to the varying evaluation criteria regarding the influence of different parameters on production, it is essential to normalize each parameter in order to establish unified standards. In the normalization process, parameters are categorized into Z-type and N-type parameters. A Z-type parameter signifies that a higher value is more advantageous for the post-frac production, whereas an N-type parameter indicates the contrary—namely, that a lower value is more beneficial for the ultimate production. The Z-type parameters are normalized using Eq. (1), while the n-direction parameters are normalized using Eq. (2).

In Eqs. (1), (2), Zn represents the result of Z-type parameter normalization without dimensionality; Z denotes the normalized Z-type parameter, with Zmax being the maximum value and Zmin being the minimum value in the normalized Z-type parameter. Similarly, Nn signifies the result of N-type parameter normalization without dimensionality, with N represents normalized N-type parameters; Nmax is the maximum value and Nmin is the minimum value of the normalized N-type parameter.

After normalization, grey correlation method is utilized to calculate the weights of geological sweet spot parameters and engineering sweet spot parameters. Subsequently, comprehensive calculations are conducted for both the geological sweet spot evaluation model and engineering sweet spot evaluation model. Finally, the dual sweet spot index set is obtained by coupling the two models. The dual sweet spot index set is then restored to the geological model according to the depth. The “geology-engineering” dual sweet spots evaluation model is achieved through the use of Petrel integrated exploration and development platform. Reference17 used Smooth Generalized Additive Model (SGAM) to model the core permeability as a function of the same log record. Utilizing this research methodology, the permeability for each well in the LX block has also been calculated. Through the fitting of the relationship between the production set and the dual sweet spot index set, the model has been successfully verified to possess high accuracy. As a result, this model can be used to inversely calculate the sweet spot distribution of other spatial locations within tight gas reservoirs. This provides a scientific theoretical basis for subsequent well location deployment and fracturing reconstruction location.

Grey correlation method

Grey correlation method18 is a multi-factor statistical analysis method, it is based on the sample data of each factor, using grey correlation degree to describe the strength, size and order of the relationship between factors. The basic idea of grey correlation method is to judge whether the relationship is close according to the similarity of geometric shapes of sequence curves. It calculates the correlation coefficient and correlation degree between the reference sequence and the comparison sequence through dimensionless processing of the data series of each factor in the system, so as to analyze the influence degree of each factor on the system behavior.

In Eqs. (3)–(5), r[X0,Xi] is the grey correlation coefficient. Δij is the difference sequence between the i-th comparison sequence and the reference sequence. A1 is the largest difference; A2 is the minimum difference; ξ is the resolution coefficient, usually 0.5; roi is the correlation degree between the i-th comparison sequence and the reference sequence. WA(i) is the weight of influencing factors calculated by grey correlation method.

The geological sweet spot evaluation model

The porosity φ is a key indicator of reservoir performance, while the permeability k provides valuable insight into the flow characteristics of the reservoir19. The gas content of a reservoir is the most direct factor influencing the enrichment and ultimate production of tight gas reservoirs, and it is determined by numerous factors. The thickness of the reservoir can indicate the abundance of gas in the stratum, with greater thickness indirectly suggesting better foundation conditions for the reservoir.

Fracturing with a high degree of fracture development can lead to the creation of a more intricate fracture network and significantly increase production. Therefore, the degree of fracture development is also considered as one of the main parameters for identifying geological sweet spots. Fracture density is introduced in this context to assess the degree of fracture development. The fracture density is introduced in this study to assess the extent of fracture development. Fracture density is defined as the quantity of fractures present within a specified thickness and radius surrounding the well. The process of quantitatively characterizing fracture density is outlined as follows: Firstly, the unit value of the ant body is extracted, followed by obtaining the normalized ant body value through a normalization process. The fracture strength factor is introduced to establish a quantitative characterization model of natural fractures based on the attribute parameters of the ant body. In this study, the fracture strength factor is specified as 3 based on the imaging logging data. In LX block, if the average fracture density exceeds 2, it is regarded as an indication of strong development. Fracture density range from 1 to 2 is classified as moderately developed. In contrast, average density below 1 is considered to exhibit weak development. (Fig. 2).

Based on the grey correlation method, the correlation coefficient and correlation degree of porosity, reservoir thickness, permeability and gas saturation with post-frac production are calculated respectively. The weight coefficient of each geological factor is determined as the ratio of the correlation degree of each factor to the total correlation degree. Finally, the geological sweet spot evaluation model is established, as shown in Eq. (6):

In Eq. (6), the weight coefficient of gas saturation is represented by a, the weight coefficient of permeability is represented by b, the weight coefficient of reservoir thickness is represented by c, and the weight coefficient of porosity is represented by d. Sgn represents the normalized gas saturation, kn represents the normalized permeability, hn represents the normalized reservoir thickness, φn represents the normalized porosity, and Nf represents the degree of fracture development.

The engineering sweet spot evaluation model

Brittleness index

The brittleness index serves as a crucial parameter for assessing the brittleness of rock. It serves as a key parameter in characterizing the capacity to develop complex fractures by hydraulic fracturing. Furthermore, it is closely associated with the effectiveness of the fracturing process20,21. Therefore, the brittleness index is regarded as the primary controlling factor. The static mechanical properties of the rock were evaluated through acoustic wave testing, as well as uniaxial and triaxial compression tests. While the dynamic mechanical properties of rock are determined through the analysis of logging data. The dynamic and static parameters obtained were subsequently fitted using polynomial equations to derive the conversion formulas for both dynamic and static parameters. The dynamic Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio are calculated as follows:

In Eqs. (7), (8), Ed represents the dynamic Young’s modulus, Vp denotes compressional wave slowness, Vs stands for shear wave slowness, μd signifies dynamic Poisson’s ratio.

Normalized Young’s modulus (En) and Poisson’s ratio (vn) along the wellbore are determined, and the rock mechanical brittleness index is calculated using Rickman’s equations, as depicted in Eqs. (9) to (11):

In Eqs. (9) to (11), Bn represents the brittleness index, En denotes the normalized Young’s modulus, vn stands for the normalized Poisson’s ratio, E signifies the Young’s modulus and v indicates the Poisson’s ratio. Emax and Emin refer to the maximum and minimum Young’s modulus respectively, while vmax and vmin represent the maximum and minimum Poisson’s ratio respectively.

Fracture toughness

Fracture toughness refers to the ability of rock material containing fractures or defects to resist the propagation of fractures until failure occurs. During the process of fracturing, the difficulty of fracture expansion is contingent upon the fracture toughness. Specifically, a higher value of fracture toughness corresponds to a greater level of difficulty in achieving fracture expansion22,23. The fracture toughness of the LX area ranges from 0.171 to 0.331 MPa∙m1/2. The core test results indicate that the LX area has low fracture toughness and limited resistance to fracture extension.

Horizontal stress difference

The horizontal stress difference refers to the difference between the two perpendicular principal stresses in the horizontal direction of rock, which directly affects the expansion direction and extension distance of hydraulic fractures. Under varying horizontal stress differentials, the opening and closure of fractures exhibit distinct patterns, with fracture extension aligning along the direction of maximum horizontal stress24,25. However, when the difference in horizontal stress is not significant, it becomes difficult to determine the direction of crack extension and accurately predict the complexity of cracks. This ultimately impacts the production.

The engineering sweet spot evaluation model

Based on the grey correlation method, with the post-frac productivity as the objective function, the weight coefficients of horizontal stress difference, brittleness index and fracture toughness were determined using the same calculation method as that of geological formations. The evaluation model for engineering formations was ultimately derived, as shown in Eq. (12):

In Eq. (12), W1 represents the weight coefficient for the brittleness index, W2 epresents the weight coefficient for fracture toughness, and W3 represents the weight coefficient for horizontal principal stress difference. Bn denotes the brittleness index, KICn denotes normalized fracture toughness, and σn denotes normalized horizontal principal stress difference.

The geology-engineering dual sweet spots evaluation model

The geological sweet spot refers to a region characterized by an abundance of oil and gas resources, coupled with favorable physical properties. This area serves as the fundamental basis for achieving efficient development of oil and gas resources. The engineering sweet spot is the area conducive to forming complex fracture network after frac, which is the guarantee of efficient development. Due to the significant heterogeneity and poor alignment between engineering and geology in the LX area, a dual sweet spot index is proposed, which involves coupling both models to obtain a ‘geology-engineering’ dual sweet spots evaluation model, as depicted in Eq. (13):

In Eq. (13), F represents the dual sweet spot index, FI stands for the geological sweet spot index, and FII denotes the engineering sweet spot index. α is the coefficient for the geological desert weight, while β is the coefficient for the engineering desert weight. α and β vary across different study areas; therefore, adjusting the values of α and β in accordance with the specific study area can effectively illustrate the interaction between engineering and geological factors.

Results

The tight gas reservoir in LX area is characterized by a continental sedimentary environment. Due to the complex and heterogeneous lithology of the Shihezi Formation, a singular evaluation model for geological sweet spots fails to provide adequate theoretical support for the subsequent fracturing program of the gas reservoir26.

Sensitivity analysis

In order to analyze the relationship between the parameters mentioned above and the production, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. (Fig. 3) It can be observed that the relationship between porosity and production is not pronounced, indicating a weak positive correlation. The same methodology is employed to examine permeability, gas saturation and thickness. The findings indicate that each factor exhibits a weak positive correlation with production.

Simulation results by geological sweet spot model

Figure 4a,b illustrate the distribution of porosity and permeability. The majority of porosity values are below 2.5%, while permeability predominantly remains under 0.3 mD. In the eastern region, gas content is relatively concentrated; however, its distribution in other areas appears to be more scattered. (Fig. 4). The relationship between porosity, permeability, reservoir thickness, gas saturation and production is established respectively. The weight coefficients of each geological parameter in LX were obtained using the grey correlation method (Table 1).

According to the weight coefficients of geological factors presented in Table 4, the corresponding geological sweet spots are calculated using Eq. (6). The distribution of these geological sweet spots across the entire LX block is determined through an interpolation method. It is evident that the geological sweet spots within the LX block are not evenly distributed, the geological properties in both the central and southern regions exhibit poor quality. (Fig. 5).

Simulation results by engineering sweet evaluation spot model

Distribution of brittleness index in LX block

The geological model of brittleness index indicates that the overall distribution range of brittleness index in the LX area, our study area, is 40 ~ 55%, with local variations reaching 80 ~ 90%. The distribution of brittleness index varies across different layers, indicating strong interlayer heterogeneity (Fig. 6). The brittleness index generally exhibits a low value, with an overall distribution range of 40 to 55%. However, there are localized areas characterized by a high brittleness index, primarily concentrated within the He3 to He7 layer s. These elevated brittleness indexes are predominantly found in the southwestern and northern regions of LX, with a smaller proportion located in the eastern area.

Distribution of fracture toughness in LX block

The fracture toughness of the LX area is relatively low, which facilitates the propagation of fractures. Taking the LXD-5 and LXD-13 as examples (Table 2), their fracture toughness ranges from 0.171 to 0.331 MP·m0.5. This suggests that the Shihezi formation permits a comparatively easy extension of hydraulic fractures.

Distribution of horizontal stress in LX block

The in-situ stress within the LX block was determined through a combination of laboratory experiment and model calculation. The results derived from Huang’s model were refined using data from Kaiser experiments, leading to the establishment of a three-dimensional principal stress model for the study area. This was accomplished utilizing the Visage geomechanics module within the Petrel integrated exploration and development platform, thereby enabling the assessment of maximum and minimum horizontal stress distributions in the LX block. This information is illustrated in Fig. 7.

The results indicate that the in-situ stress in the southwestern region exceeds 30 MPa, whereas in the northeastern region it is below 27 MPa. The longitudinal stress exhibits significant variation across different small layers, with a minimum horizontal principal stress distribution range of 26 to 35 MPa and a maximum horizontal principal stress distribution range of 27 to 38 MPa. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the He2 and He3 layer s of the upper Shihezi Formation demonstrate high-stress characteristics. Furthermore, the overall horizontal stress difference across the entire study area is around 2 MPa. Due to this slight horizontal stress differential, determining the initiation direction of artificial fractures becomes uncertain, thereby increasing the likelihood of multiple fractures occurring near the wellbore.

The weight coefficients of each engineering sweet spot parameter in LX were determined using the grey correlation method (Table 3).

The distribution of engineering sweet spots in the LX block is derived using Eq. (12), employing the same methodology as that used for geological sweet spots. It is evident that the engineering sweet spots in the LX area are generally favorable, with most FII values exceeding 0.5. (Fig. 8).

Simulation results by geology-engineering dual sweet spots model

Based on Eq. (13) and the gas-phase attributes in the geological model as constraints, a coarsening of differences in the geological model was conducted, leading to the establishment of a dual sweet spot model for geological-engineering integration. It is generally observed that when the dual sweet spot index F exceeds 0.5, there is a high level of production, making this range the primary recommendation. In the interval where F falls between 0.3 and 0.5, it is regarded as a recommended area; conversely, when F is below 0.3, it indicates an inefficient zone with typically no industrial oil and gas production. The dual sweet spot analysis of each interval within the Shihezi Formation indicates that the key layers He2, He5, and He6 exhibit significant potential. It is evident that the dual sweet spot index for layers He1, He7, and He8 in most regions falls below 0.3, while the distribution of layers He3 and He4 appears excessively dispersed (Fig. 9).

Discussion

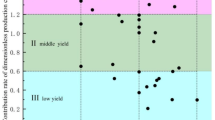

In accordance with the industrial oil flow production evaluation standard (Q/SY TZ 0026-2000), the low/medium/high well boundaries of 3000 and 10,000 m3/d have been defined for depths ranging from 1000 to 2000 m. The dual sweet spot index of each well is calculated using Eq. (8), and the relationship between the dual sweet spot index of each well and the production is established (Fig. 10).

A strong correlation is evident between the single-layer dual sweet spot index and the gas production (Fig. 10). The results have been fitted with a regression prediction model, leading to the derivation of a quantitative evaluation model for the post-frac effect in the LX area, as illustrated in Eq. (14):

Based on the calculations for single-layer fracturing. The dual sweet spot index, error and predicted coincidence of fractured Wells in the LX area (Table 4). When F < 0.3, the forecasted output falls below 3000 m3/d, failing to meet industrial air flow standards; therefore, specific production capacity forecasts are not carried out at this time. The analysis of single-layer fracturing reveals a strong correlation between production and F. A regression model was fitted based on production capacity to predict well production rates and compared with actual gas production. With an error limit set at 20%, it was found that the predicted coincidence rate reached 85.7%.

Through the analysis of wells that exhibit deviations from predicted values, it has been observed that some wells’ production exceeds anticipated levels. This discrepancy can be attributed to the development of natural fractures surrounding the wellbore. The artificial fractures created through hydraulic fracturing interact with nearby natural fractures, thereby enhancing reservoir stimulation and contributing to additional productivity. Meanwhile, the wells exhibiting actual production levels lower than the predicted values are attributed to fluid damage. The prolonged flowback period leads to fracturing fluids being trapped within the formation, which consequently results in reservoir damage.

The production evaluation of single layer post-frac is in line with high reliability. The actual working area is utilized through partial pressure and combined tests to verify the accuracy of the model by comparing post-frac production with the theoretical value predicted by the model (Table 5). The production of the combined layer also follows the regression model, confirming the accuracy of the dual sweet spot index model and aligning with the actual situation of LX area. Clearly, the fracturing quality evaluation model demonstrates high reliability for tight gas reservoirs in the LX area and provides a crucial foundation for optimizing fracturing programs in later stages.

This model allows for the adjustment of main control factors based on the specific characteristics of the study area, thereby enabling the development of a comprehensive evaluation model tailored to that region. In cases where the main controlling factors are not clearly identified, one can calculate the grey correlation degree of most parameters using the grey correlation method. Subsequently, the controlling factors can be determined by ranking these degrees of grey correlation.

Conclusion

Compared to other methods, this approach takes into account a broader range of factors and can be adapted to varying conditions across different regions. A dual sweet spot evaluation model integrating geological and engineering aspects was developed within the three-dimensional space of the entire research block. This model effectively illustrates the comprehensive distribution of sweet spots in various gas-bearing areas, thereby providing theoretical support for predicting and optimizing development strategies for sweet spots in three-dimensional space.

-

1.

In LX block, a strong correlation is observed between production and the dual sweet spot index F. The comparison of theoretical and actual production for each well demonstrates an 85.7% predictive agreement. This finding indicates that the evaluation model is highly reliable.

-

2.

Based on the dual sweet spot evaluation model, we established the critical threshold for the dual sweet spot index. When the F exceeds 0.5, the corresponding area is designated as a priority development zone. Conversely, when the F falls below 0.3, the corresponding area is deemed to have no developmental potential.

-

3.

The simulation results indicate that He2, He5, and He6 layers of the Shihezi Formation in the LX area demonstrate favorable fracability. Consequently, these three formations should be prioritized when developing fracturing plans.

In the short term, by considering geological and engineering factors, we can more accurately identify areas with high potential for fracturing operations, thereby reducing ineffective efforts. In the long term, precise models offer a comprehensive understanding of reservoir characteristics, allowing fracturing operations to align more effectively with reservoir geology. This ultimately enhancing gas recovery, prolonging the production life of the field, and achieving optimal resource development.

Limitations: (1) The accuracy of a geological model is contingent upon the quality of the data, which is inherently limited by factors such as accuracy, resolution, and coverage. (2) The relationship between geological and engineering factors is intricate and nonlinear. Consequently, when addressing this coupling relationship, certain simplifications and approximations may be necessary within the model.

In the future, this model can be further deepened: (1) Utilizing high-precision seismic imaging technology to acquire more detailed information regarding formation structures and fracture distributions, while closely integrating this data with geological engineering models, enhances the resolution and reliability of sweet spot identification. (2) Enhance the model’s capacity to comprehend intricate relationships between geological structures and engineering factors.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Chu, C. & Xie, Q. Productivity evaluation of fractured horizontal Wells in tight gas reservoirs. China Petrol. Chem. Stand. Qual. 44(03), 11–13 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Progress and application of unconventional reservoir fracturing technology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 33(S1), 149–158 (2012).

Xia, X. et al. Application of array acoustic logging in gas bearing evaluation of tight sandstone gas reservoirs. Nat. Gas Explor. Dev. 47(03), 77–84 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Logging evaluation of brittleness index of tight oil reservoir in Yanchi area. Petrol. Geol. Eng. 38(01), 6–12 (2024).

Xia, H. et al. Prediction of shale oil reservoir sweet spot based on well logging data. J. Southwest Petrol. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 43(04), 199–207 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Predicting the engineering sweet spot of coal-bed methane reservoirs: a case study from Central China. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-09751-7 (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. Analysis of tight oil accumulation conditions and prediction of sweet spots in Ordos Basin: A case study. Energy Geosci. 03(04), 417–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engeos.2021.09.002 (2022).

Jiang, X. et al. Research and application of evaluation method of shale gas geology-engineering fracability. Nat. Gas Oil 40(04), 68–74 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. A new method for shale gas reservoir fracability evaluation. Nat. Gas Geosci. 26(06), 1165–1172 (2015).

Huang S. Evaluation of fracability of tight sandstone reservoir in S area. Northeast Petroleum University (2022).

Zhou, Q. et al. Fracturing ability evaluation of shale reservoir engineering considering fracturing induced effect. Petrol. Geol. Dev. Daqing 43(06), 155–162 (2024).

Huang, F. et al. A logging data based method for evaluating the fracability of a gas storage in Eastern China. Sustainability 16, 3165. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16083165 (2024).

Gong, Y., El-Monier, I. & Mehana, M. Machine learning and data fusion approach for elastic rock properties estimation and fracturability evaluation. Energy AI 16, 100335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyai.2024.100335 (2024).

Zeng, F. et al. Fracability evaluation of shale reservoirs considering rock brittleness, fracture toughness, and hydraulic fracturing-induced effects. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 229, 212069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2023.212069 (2023).

Peng, C. et al. Evaluation of tight sandstone mechanical properties and fracability: An experimental study of reservoir sand−stones from Lufeng Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, Northern South China Sea. Processes 11, 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11072135 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Upper Paleozoic tight gas sandstone reservoirs and main controls, Linxing block. Oil Gas Geol. 42(5), 1146–1158 (2021).

Al-Mudhafar, J. Integrating lithofacies and well logging data into smooth generalized additive model for improved permeability estimation: Zubair formation, South Rumaila oil field. Mar. Geophys. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11001-018-9370-7 (2019).

Sun, F. The method of grey relational degree analysis and its application are briefly discussed. Sci. Technol. Inf. 17, 880–882 (2010).

Zhang, H. et al. Reservoir characteristics and main controlling factors of Chang 6 Member in Yule area, Ordos Basin. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 51(04), 531–542 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Research progress and prospect of unconventional reservoir brittleness. Geophys. Prospect. Petrol. 58(06), 1499–1507 (2023).

Wu, B. et al. Effect of fracability index on fracture propagation: A case study of LF oilfield in South China Sea. Petrol. Drill. Tech.. 51(3), 105–112 (2023).

Zhao, N. et al. Fracturing ability evaluation of tight sandstone based on mechanical tests under formation conditions. Well Logg. Technol. 46(02), 127–134 (2022).

Gao, H. et al. Evaluation of fracturing property of shale oil reservoir based on logging data. Prog. Geophys. 33(02), 603–612 (2018).

Xiong, J. et al. Study on influencing factors of stress sensitivity of artificial fracture in deep tight reservoir. Nat. Gas Geosci. 35(04), 563–572 (2024).

Yin, S. et al. Study on opening conditions and expansion rules of natural and hydraulic fractures in fractured reservoir. Petrol. Drill. Tech. 52(03), 98–105 (2024).

Sun, Q. et al. Physical characteristics and influencing factors of Upper Paleozoic reservoir in LinxingShenfu block, eastern margin of Ordos Basin. Coal Geol. China 33(01), 42–51 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Hubei Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Engineering (Yangtze University) (Grant No.: YQZC202410) for the financial support of this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hubei Key Laboratory of Oil and Gas Drilling and Production Engineering (Grant No.: YQZC202410).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Yi Liu, Shanyong Liu; Writing—original draft: Yi Liu; Writing—review and editing: Yi Liu, Shanyong Liu; Validation: Biao Yin, Yan Zhang; Software: Biao Yin; Project administration: Yishan Lou; Investigation: Shanyong Liu; Data curation: Yi Liu, Shanyong Liu, Biao Yin.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Liu, S., Lou, Y. et al. A novel approach for evaluating geology-engineering dual sweet spots in tight gas reservoirs in the LX block of China. Sci Rep 15, 6061 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90371-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90371-y