Abstract

This study investigates the genetic structure and demographic history of contemporary Thai populations from Tak and Ranong, two border provinces between Thailand and Myanmar with complex immigration histories. We analyzed 20 Y-SNP markers (327 samples) and 24 Y-STR profiles (241 samples), along with published datasets, and observed significant genetic differentiation between these regions. Tak is dominated by O2a2b1a1a (44.53%) and O1b1a1a (21.17%). The presence of NO1 (14.6%) suggests genetic contributions from nearby populations such as the Karen, Lawa, and Khuen. Notably, Tak shows low gene diversity (GD) at the DYS391 (0.2208), contrasting with Ranong (0.5247) and the overall Thailand population (0.4708). Ranong exhibits a more diverse haplogroup distribution, with prominent frequencies of O1b1a1a (20.75%), F (16.98%) and O2a2b1a1a (13.21%). The presence of haplogroups K (11.32%) and R* (7.55%) reflects a genetic connection with the Maniq or other mainland Negrito groups, as well as historical gene flow from South Asia. These findings enhance our understanding of the genetic landscape shaped by migration and localized admixture. We also expanded the Thailand Y-chromosome database with novel Y-STR haplotypes, updated forensic parameters and Y-haplogroup frequencies, providing valuable resources for paternal ancestry inference and kinship verification in both forensic science and population genetics

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thailand is in central Mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA) with extensive population diversity. There are 62 linguistic groups across Thailand including 24 Tai, 22 Austroasiatic, 11 Sino-Tibetan, 3 Austronesian, and 2 Mien-Hmong groups1. Alongside this diversity, Thailand also hosts one of the world’s largest stateless populations, with over 500,000 registered individuals2. Statelessness is defined as the absence of recognized as a citizen of any country under the operation of its law3. It affects at least 4.6 million people globally, though this number is likely a substantial underestimation4. In Thailand, highland ethnic groups such as the Akha, Lahu, Hmong, Lisu, Karen, and Shan constitute a significant portion of the stateless population5,6. The Thai diaspora in southern Myanmar is another group struggling with citizenship due to insufficient official documentation or evidence7. Similarly, the Moken (sea nomads inhabiting the Andaman Sea coastline and islands, including Chang Island in Ranong province) also face difficulties in acquiring citizenship due to their non-sedentary lifestyle8,9. Migrants from neighboring countries, particularly Myanmar, further contribute to Thailand’s stateless population5. As of April 2023, approximately 2.5 million regular migrants resided in Thailand, 75% of whom originated from Myanmar10. Stateless individuals in Thailand experience significant socioeconomic disadvantages due to their lack of identity cards, limiting their access to essential services like education, employment, and healthcare, and perpetuating cycles of poverty and marginalization11,12,13.

DNA testing has been assisted in verifying familial relationships for visa petitions and migration screening14,15,16. At least 17 European nations and over 20 countries globally have incorporated parental DNA testing into their family reunification and immigration procedures17. For instance, Germany encourages using genetic evidence for family reunification in cases where traditional documentation is insufficient17,18. Comparing the STR profile of a stateless individual with that of established relatives holding citizenship provides corroborative evidence of biological relatedness, supporting identity verification and legal recognition in the absence of traditional documentation. However, this method faces limitations when appropriate comparison individuals are unavailable. Y-chromosome single nucleotide polymorphisms (Y-SNPs) haplogroup analysis is a powerful method for tracing paternal ancestry, offering a complementary approach to Y-STRs. Y-SNPs have significantly lower mutation rates than Y-STRs (0.75–0.89 × 10–9 vs. 0.86–1.25 × 10−4 per locus per year)19. This makes them useful for the reconstruction of paternal lineages over longer timescales. The frequencies of Y haplogroups in different populations provide valuable markers for differentiating paternal lineages and inferring ancestry20. Previous studies have explored the paternal genetic landscape of Thailand, focusing on various aspects of population history and genomic structure21,22,23,24,25,26. The analysis of 928 male-specific portions of the Y chromosome (MSY) samples from 59 populations across diverse geographic regions and ethnic groups, showed the contrast between paternal and maternal genetic histories and postmarital residence patterns25. Previous genome-wide and uniparental markers studies revealed a complex population landscape of Thailand and MSEA21,22,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,32.

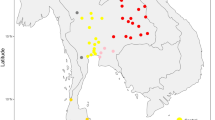

This study investigates the paternal genetic landscape of contemporary Thai populations in Tak and Ranong (Fig. 1), provinces strategically located along the Thailand-Myanmar border and host three of the six permanent border crossings. These regions are particularly significant due to their roles in immigration and statelessness. We utilized SNaPshot technology for Y-SNPs analysis33 targeting specific SNPs to infer Y-haplogroups relevant to our research (Fig. 2), due to the cost-effectiveness, robustness, and established reliability in previous studies34,35,36,37,38,39. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was employed for Y-STR profiling to enhance the resolution of the genetic data. By integrating newly generated Y-SNPs and Y-STRs profiles with published datasets, we aim to expand the Y-chromosome database and contribute a more comprehensive understanding of the genetic structure and demographic history of these populations. Acknowledging the ethical implications of using genetic data, especially in contexts of immigration and statelessness, we stress the need for responsible and ethical applications of our findings.

Geographic Distribution of Samples in current and previous studies. This figure illustrates the geographic origins of samples collected in the present study and those previously reported by Kutanan et al.25. Permanent border crossings are indicated for reference. The map was produced using QGIS 3.34.140 and subsequently refined in Inkscape 1.3.2.

The cladogram of the 20 Y-chromosomal binary polymorphisms analyzed in this study. The Y-SNPs analyzed are indicated on each branch, with the corresponding haplogroups shown at the terminal nodes, based on the Haplogroup Tree 2019–2020 v15.73 (https://isogg.org/tree/index.html).

Results

Y chromosome diversity and its distribution

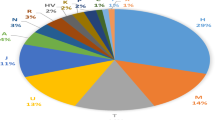

Analysis of 327 Thai male samples from Tak and Ranong (see Supplementary Table S1) identified 17 distinct Y-haplogroups, with frequency distributions summarized in Table 1. The predominant haplogroups were O1b and O2a, comprising 74.45% of the Tak population and 49.06% of the Ranong population. These findings align with previous research, which highlighted the dominance of these haplogroups in Thailand25. However, subhaplogroup distributions varied significantly between the two regions. In Tak, the subhaplogroup frequencies were as follows: O2a2b1a1a (44.53%), O1b1a1a (21.17%), and NO1 (14.23%). In Ranong, the haplogroup frequencies were: O1b1a1a (20.75%), F (16.98%), O2a2b1a1a (13.21%), and K (11.32%). Haplogroup O1b1a1a, present at notable frequencies in both Tak (21.17%) and Ranong (20.75%), suggests potential shared ancestry or gene flow with Austroasiatic-speaking populations such as the Htin, Khmer, Khmu, Lawa, Bru, and Mlabri, where O1b1a1a reaches frequencies exceeding 80%25,41,42. Haplogroup NO1 was relatively frequent in Tak (14.23%) but absent in Ranong. This may reflect genetic contributions from the nearby Lawa hill tribe, where 56% of haplogroups belong to the N clade25. Haplogroup F (M89) was significantly more prevalent in Ranong (16.98%) than in Tak (2.92%), and the K haplogroup was also higher in Ranong (11.32%) compared to Tak (1.82%). The presence of non-Southeast Asian haplogroups, such as R, in both populations (7.55% in Ranong, 0.36% in Tak) highlights the complex genetic landscape of the region.

Comparative analysis of populations from Thailand, South Asia, and East and Southeast Asia (ESEA) revealed distinct Y-haplogroup distribution patterns, as illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4. The O2 lineage was predominant in Tak (53.65%) but less frequent in Ranong (30.20%). The prevalence of O2 clade haplogroups varied significantly across Thai populations, ranging from 66.67% in Palaung to 3.45% in Htin. The notably high frequency of O2 in northern Thailand, particularly among Palaung, Tak, Shan, Karen, Nyahkur, and Khonmueang populations (exceeding 45%)22,25, suggests the influence of historical migrations and demographic factors. This distribution is consistent with the broader East Asian prevalence of O2, particularly among Sino-Tibetan populations where O2-M122 is a dominant lineage. O2-M122 accounts for 50 to 60% of the Han Chinese43. The O2a2b1a1a subclade was particularly prevalent in Tak (44.53%), like its high frequency in the Dai population from Yunnan province, southwest China (41.82%). SOURCEFIND analysis indicates that the Dai population contributed between 2.4 and 22.8% genetic ancestry to the Khonmueang, Khuen, Lue, and Yuan populations29 revealed potential genetic affiliations between the Tak population and these groups. O2* is prevalent in East and Southeast Asia, particularly in Malaysia and Indonesia, but occurs less frequently in South Asia (12.47%), primarily among Austroasiatic and Tibeto-Burman groups. Haplogroup O1a is strongly associated with Austronesian-speaking populations from Taiwan, Philippines, and Indonesia which exhibit high O1a frequencies (47.19%, 42.46%, and 26.42%, respectively)44. The O1a haplogroup is highly prevalent in Taiwan Mountain Tribes Aborigines (TwMtA) (85.35%), while mainland East Asian populations show much lower frequencies (7.59% in China). In Thailand, O1a frequencies also vary significantly, with Ranong showing a higher prevalence (5.66%) compared to Tak (0.73%). Previous studies have identified evidence of Austronesian-related ancestry in the southern Thai population, including the presence of mtDNA haplogroups B4a1a and M7c1c322. They are primarily distributed among aboriginal Taiwanese and Island Southeast Asian (ISEA) populations. The signal of Austronesian-related ancestry in the southern Thai population was also inferred using the autosomal haplotype-based method SOURCEFIND29. These findings collectively suggest a possible Austronesian admixture component within the Ranong population. The higher Y-SNPs haplotype diversity in Ranong (0.8970) compared to Tak (0.7317) indicates greater genetic variation and potentially more gene flow in Ranong.

Pie charts showing Y-haplogroup distributions across South Asian, East, and Southeast Asian populations. Supplementary Table S2 provides details on the published datasets used in the analysis. The map was created using the “rnaturalearth” R package (https://github.com/ropensci/rnaturalearth) with data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

Comparative distribution of major Y-haplogroups. This stacked bar plot illustrates the relative frequencies of the major Y-chromosome haplogroups in different populations from India, Thailand, China, and Taiwan, comparing data from the current study with previously published findings. (see Supplementary Table S2 for the additional details of populations).

Fisher’s exact test assessed haplogroups distribution differences between Tak, Ranong, and other Thai populations. The results (Supplementary Fig. S1) indicated significant deviations in the haplogroup frequencies for Tak compared to all other groups. Although Ranong showed some similarity to southern Thai populations, it also exhibited unique haplogroups profile. These findings underscore the importance of region-specific Y-haplogroup databases for forensic applications, as they can more accurately reflect the genetic diversity within the regions.

Relationship with populations in Thailand, South Asia, and East Asia

Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) of 20 Y-SNP markers shows genetic differentiation among the studied populations (Supplementary Table S3). In comparison between Tak and Ranong, 9.36% of genetic variance was between populations, while 90.64% was within populations (p < 0.05). The broader analysis including 126 populations from Thailand, China, India, and Taiwan reveals that 13.30% of genetic variation arises from differences between countries, while 14.28% is due to variation among populations within the same country. The majority of genetic variation (72.42%) is observed within populations, indicating that genetic diversity primarily occurs at the individual level rather than between populations or countries. These findings align with Kutanan et al.25, who found that 88.88% of genetic variance in 928 individuals from 59 Thai populations was within populations. Notably, a significant test (p = 0.01) indicates that this observed within-population variation is significantly lower than expected under a random mating model, suggesting underlying population structure or other factors reducing genetic diversity within populations.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was employed to visualize genetic relationships among the studied populations based on their Y-SNP profiles. Figure 5 effectively captured the underlying genetic structure, as indicated by a low stress value of approximately 0.0364. Indian populations in the East and Northeast regions who speak Austroasiatic (AA) or Tibeto-Burman (TB) languages, such as Munda, Kharia, Bhumij, and Santhal, along with Bhuiyan (BhuY), who speaks Indo-European, form a cluster that differentiates them from other Indian and ESEA populations. Notably, these Austroasiatic-speaking groups exhibit a closer affinity with Austroasiatic and Kra-Dai-speaking populations in Thailand, including Mon, Lawa, Suay, and Central Thai. This pattern aligns with previous findings of Southeast Asian admixture within the Munda branch of Austroasiatic populations in India45,46,47. The shift of SouthernThai_TK (STTK) towards the Indian cluster in the NMDS plot aligns with previous studies. Southern Thai population exhibits a significant of South Asian mtDNA haplogroups (~ 35 to 45%), approximately 35% of South Asian Y-haplogroups, and a substantial South Asian admixture22,29,48,49. The Indian populations that are in proximity to STTK in the NMDS plot display significant linguistic and geographic diversity, including both Indo-European and Dravidian-speaking groups from various regions. Despite its location in southern Thailand, Ranong shows a closer genetic affinity with Central Thai (CtC, CtE, CtN, CtW), and Mon (MoC, MoN, MoW) populations than with STTK, suggesting a distinct paternal lineage history. The position of Tak in the NMDS plot is notably close to Gelao (Gel), Karen (KR), Shan (Sha), Palaung (PA), Nyahkur (Nya), Han and Taiwan Han (TwH). Despite the geographical distance between Tak and Taiwan, the observed genetic proximity in the NMDS plot (Fig. 5a) is notable and it is clearly illustrated by the Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5b). The Taiwanese populations are primarily descended from Han Chinese migrants originating from various provinces in China. Genetically, they exhibit greater affinity to Southern Han Chinese populations than to Northern Han Chinese populations50. This genetic affinity likely reflects historical interactions and migrations between Kra-Dai populations and Southern Han Chinese. Although a genetic relationship between Southern Thai (Ranong and STTK) and TwMtA was expected due to evidence of bidirectional admixture with the Austronesian-speaking Nayu, who genetically shift toward other Austronesian-speaking groups from Island Southeast Asia (ISEA)29, the TwMtA positioned distinctly apart from other populations and remained distant from the Southern Thai. This distinct placement may be due to their low Y-chromosome diversity, likely driven by genetic drift, setting them apart from other Austronesian-speaking groups44. The NJ phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5b) reveals four main clusters with distinct linguistic and geographic distributions. Cluster I includes populations with diverse linguistic affiliations, such as Sino-Tibetan (e.g., Karen, Han, TwH), Austroasiatic (e.g., Palaung), and Kra-Dai (e.g., Gelao, Tak), indicating genetic connections despite linguistic differences. These relationships may stem from historical interactions or shared ancestry, possibly influenced by Han Chinese. Indian populations form two separate clusters: Cluster II (northeastern and eastern India) features Tibeto-Burman speakers (e.g., Kuki, Mara) and Austroasiatic speakers (e.g., Munda, Santhal), reflecting geographic proximity to Cluster I. Cluster III includes predominantly Thai populations alongside Kra-Dai speakers from China (e.g., Dai, Li), while Cluster IV represents additional Indian groups. The NJ tree complements NMDS analyses, offering a comprehensive view of the paternal genetic landscape of the studied populations.

Population relationships based on the Y-SNP genetic distance matrix of 126 populations. The three-dimensional non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot shows Dimensions 1 and 2. (a) Neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree. (b) Branch lengths are proportional to genetic distance. NMDS plots of Dimensions 1 vs. 3 and Dimensions 2 vs. 3 are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. Population details are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Incorporating Y-STR analysis for enhanced genetic diversity assessment

The Y-STR profiles from Tak and Ranong are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Among 327 samples, we identified 289 distinct profiles, with 23 haplotypes shared by multiple individuals. One haplotype associated with haplogroup O2a2b1a1a (O-M133) was found six times in Tak, indicating recent common ancestry. Forensic statistical parameters were calculated, and the results are detailed in Supplementary Table S4. Y-STRs haplotype diversity is 0.9964 and 0.9987 in Ranong and Tak, respectively. These values align with previous studies in various populations from Thailand21,26,51. This significant genetic variation within these populations is valuable for forensic applications. The average GD across all markers is 0.6478 in Tak and 0.7402 in Ranong. Kampuansai et al.21 observed similar variability in GD values across different populations. Lawa and Lua showed lower GD values of 0.5037 and 0.4532, respectively, while Shan exhibited the highest GD of 0.7039. The multicopy marker DYS385ab showed the highest GD value in the Ranong and Tak populations, with 30 and 42 haplotypes, respectively. Conversely, DYS391 showed the lowest GD across all markers, with a significant difference in values: 0.2208 in Tak, 0.5247 in Ranong, and 0.4708 in the overall Thailand population.

We conducted NMDS analysis using Y-STR haplotypes, which included 10 shared STR loci from 127 populations in 13 countries. In an ideal scenario, the Y-STR data would be derived from the same populations used in the Y-SNPs analysis. However, due to limitations in data availability, the Y-STR data utilized in this NMDS analysis originates from a distinct set of populations across Asia. Despite this, this approach can still provide complementary insights into recent genetic relationships and the population history of Tak and Ranong. The result of the NMDS analysis is presented in Fig. 6a. As expected, populations from the same country or region tend to cluster together, reflecting shared genetic ancestry. For example, Cambodian populations form a tight cluster, indicating a close genetic relationship (Fig. 6a). While South Asian admixture in Cambodians has been reported47, the cluster of Cambodians and Indians is exclusively observed in the NMDS2 vs. NMDS3 plot (supplementary Fig. S3). Its absence from NMDS1 vs. NMDS2, NMDS1 vs. NMDS3, and the NJ tree indicates that this relationship is driven by weaker genetic signals reflecting subtle or localized admixture events. Indian populations exhibit high genetic diversity, reflected in their dispersed distribution in the NMDS space. However, they form a distinct cluster separate from other populations, suggesting a unique overall genetic signature (Fig. 6). Notably, Tamil and Irula (Dravidian ethnolinguistic populations from southern India) form a distinct subcluster closer to the Ranong population in the NMDS space. This observation suggests that these southern Indian populations represent a potential source for the Y-haplogroup R* observed in Ranong. Previous studies corroborate this, showing South Asian admixture in various Thai populations, such as SouthernThai_TK (Thai-speaking), and SouthernThai_AN (Malay-speaking group from Southern Thailand, also known as “Nayu”)29,30,49. Changmai et al. employed ADMIXTURE analysis and revealed a component of South Asian ancestry that exceeds 5% in Thai populations, potentially linked to southern Indian groups such as Irula and Mala30. The NMDS analysis revealed a closer affinity of the Tak population with East Asian populations, particularly Han Chinese (various locations) and Dai (Yunnan, China), based on their spatial proximity in the NMDS plot. This finding aligns with their geographic distribution and potentially reflects shared ancestry. Furthermore, the observed genetic relationship between Tak and Dai supports the previously proposed two-route dispersal model for certain Kra-Dai languages29, which complements the historical linguistic scenario outlined by Baker and Phongpaichit52. Interestingly, the Tak population also exhibits a genetic connection to the Dhimal, a Sino-Tibetan speaking group residing in West Bengal, India. Although unexpected based on geographic distance, this finding warrants further investigation to explore potential historical connections or ancestral migrations. Ranong shows genetic alignment with populations from China including Han, Wa, Lahu, and Lisu (Fig. 6). This suggests possible recent interactions or admixture with Chinese migrants. The NMDS plot shows shared ancestry between Ranong and Malay (MY_1), while the NJ tree places them in separate clusters. This discrepancy reflects methodological differences: NMDS captures overlapping genetic signals and admixture, whereas the NJ tree simplifies relationships hierarchically. The NMDS result aligns with previous studies indicating that Southern Thai populations, including Ranong, derive significant ancestry (~ 65%) from the Malay-speaking Nayu, closely related to Austronesian groups from Island Southeast Asia29. The NJ tree based on Y-STR Rst distances for 127 populations reveals four broad clusters (Fig. 6b). Indian populations forming a distinct group, except for Irula, Tamil, Rajbanshi, Paliya, and Dhimal, which cluster with Thai and Chinese populations. The remaining clusters predominantly comprise populations from Taiwan and Cambodia. These clusters exhibit higher diversity and are less distinct compared to the Y-SNP-based NJ tree. To further explore genetic diversity, we conducted Network analyses for the O1b1a1a and O2 clades using Y-STR haplotype data. These analyses revealed substantial haplotype diversity within these clades, with multiple overlapping reticulations indicating complex paternal lineage relationships (supplementary Fig. S4).

NMDS plot and a neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree derived from the 10 STR Rst genetic distance matrix of 127 populations. The NMDS plot displays Dimension 1 versus Dimension 2 (a) A neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree of 127 populations. The lengths of bars represent genetic distances. NMDS 1 vs NMDS3 and NMDS2 vs NMDS3 plots can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3. Refer to supplementary table S6 for additional information for each population.

Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor (TMRCA) was computed using Y-STRs profiles (Supplementary Table S5). The TMRCA estimated for haplogroup O2a2b1a1a-M133 in the Tak population is 4572.3–4647.6 years before present (YBP), which are in accordance with previous findings for Thai populations (6210 ± 3590 YBP) reported by Trejaut et al.44. The TMRCAs for haplogroup O1b1a1a-M95 in the Ranong (5,099.9–5,253.8 YBP) and Tak (5315.6–5404.9 YBP) populations are relatively close, indicating a shared paternal lineage divergence within a similar timeframe. However, the broader 95% confidence interval TMRCA for O1b1a1a-M95 reported by YFull.com is 8300–13,300 YBP. This discrepancy highlights the need for further studies in TMRCA estimation. The younger TMRCA estimate (7042.7–7209.8 YBP) for haplogroup NO1 in Tak, compared to the 34,300–39,300 YBP range from YFull.com, suggests potential misidentification of haplotypes. This may result from the absence of markers for N clade haplogroup determination in our multiplex PCR method, leading to incorrect classification of N clade haplogroups as NO1. Thus, the TMRCA for NO1 in Tak appears unusually young. The high frequencies of haplogroup N in geographically neighboring populations, such as the Lawa (21.28%) and Khuen (17.65%)22, suggest a potential ancestral connection. This is supported by the NMDS analysis (Fig. 3), which shows the genetic affinity between Tak and Khuen. Therefore, the NO1 haplogroup in Tak may represent various N clade haplogroups inherited from these neighboring populations.

Discussion

This study investigates the paternal genetic landscape of Tak and Ranong provinces to provide insights into regional population history and assess the potential of Y-chromosome data to support claims of belonging and facilitate access to essential services for stateless individuals. Our analysis revealed significant differences in Y-haplogroup distribution between Tak and all other populations examined. In contrast, Ranong showed no significant difference in Y-haplogroup distribution from seven populations, including SouthernThai_TK (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Notably, haplogroup K was observed at a frequency of 11.32% in Ranong, compared to only 1.82% in Tak. Haplogroup K-M9 is an ancient lineage with an estimated origin in the Middle East approximately 40,000–53,900 years ago53. The Y chromosomes of two ancient Eurasian individuals, Ust’-Ishim and Oase 1, belong to haplogroups K(xLT) and F (a lineage closely related to K), respectively54,55. In Thailand, haplogroup K was detected at 100% in the Maniq, a hunter-gatherer Negrito group from Southern Thailand, and at lower frequencies in Kalueang (5.88%), SouthernThai_TK (5%), and HtinPray (3.45%)24,25. ADMIXTURE and qpAdm analyses inferred the presence of Onge-related ancestry in the Maniq (74%) and Htin (18%)30. This suggests a link between this ancient East Eurasian lineage and haplogroup K in these groups, as well as in Ranong and, to a lesser extent, Tak. This suggests a very ancient connection, possibly reflecting early migrations into Southeast Asia. The Maniq’s geographical proximity to Ranong and Htin’s proximity to Tak suggests potential gene flow. The presence of basal ancient mtDNA lineages (M21d and M46) in Moken females56 raises the possibility of similar ancient Y-chromosome lineages, such as K, in Moken males, potentially contribute to the Ranong gene pool. The presence of haplogroup K in the Moken, Maniq, and established Ranong population suggests shared regional ancestry, which can be used as supporting evidence in citizenship contexts, particularly when traditional documentation is lacking. This deep-rooted presence suggests a long-term association of these groups with the region.

The presence of Y-haplogroup R* (7.55%) in Ranong provides genetic evidence of West Eurasian or South Asian ancestry. This aligns with the prevalence of haplogroup R in India and Pakistan57 where R1a1* reaching high frequencies (up to 72.22%) in Brahmins58. While specific historical records are limited, archaeological finds from the ancient Ranong port of Phu Khao Thong (first-fourth centuries AD) provide evidence of extensive maritime trade with South Asia. These finds include Indian Srivatsa seals, beads of glass, stone, and gold (from Vietnam, India, and Persia), and Roman carnelian intaglios59. These provide tangible evidence of South Asian influence in the region. The presence of R* in Ranong thus likely reflects these long-standing interactions and suggests that Ranong was part of this broader network of cultural and genetic exchange. This aligns with genome-wide studies that have detected South Asian admixture in various present-day Southeast Asian populations. The admixture proportions ranging from 4 to 12% and admixture dates between ~ 450 and 1600 years before present (YBP) were determined in various population from Thailand22,25,29,30,49. Although Y-haplogroups R2 (11%) and R1a1a1b2a2a (6%) were observed in LaoIsan25, genome-wide autosomal analysis using fastGLOBETROTTER provided further confirmation of South Asian admixture in this population, supporting the association of Y-haplogroup R* with Indian ancestry29. Both the NMDS analysis of Y-STR data (Fig. 6a) and the NJ phylogenetic tree (Fig. 6b) show a relationship between Ranong and Indian populations. The absence of R* does not rule out South Asian admixture, as demonstrated in Khonmueang and Palaung by Changmai et al.29. The presence of R* in stateless individuals in Ranong, especially if found in other established local populations, could provide valuable evidence of historical ties to the region, relevant in certain citizenship contexts.

This study found a substantial frequency of haplogroup NO1 (14.23%) in Tak, but it was absent in Ranong. Given our limited marker panel (M175 for O, lacking M231 for N), we suspect these individuals in Tak belong to the N clade. Previous research supports this, showing NO1 at low frequency (1.28%) only in LaoIsan. However, haplogroup N* (N, N1, and N1a2) has a wider distribution across Thailand (1.28–21.28%). Haplogroup N-M231 is prevalent in the Lawa (21.28%), moderately frequent in the Karen (7.02%), and N1a2 is dominant in Khuen (17.65%)22. While historical migration records for the Tak area are scarce, geographically proximate groups like Karen, Lawa, and Khuen are potential sources of N* in Tak. NMDS analysis reveals closer genetic affinity between Tak and Karen compared to Lawa and Khuen (Fig. 5), corroborated by the NJ tree, which shows Tak clustering closely with Karen subgroups Skaw and Pwo (Fig. 6b).This suggests a stronger potential Karen contribution. Although haplogroup N (specifically N1b*) is a major paternal lineage among Tibeto-Burman populations60,61,62, its high frequency (21.28%) in the Austroasiatic-speaking Lawa suggests admixture between Lawa and Tibeto-Burman groups, possibly via contact with the Karen. This hypothesis is supported by historical records and genetic analysis. The significant Skaw Karen migrated into Lawa territories around 1850, resulting in intermarriage and cultural exchange63,64,65. SOURCEFIND and qpGraph analysis have also identified Tibeto-Burman-related ancestry within the Lawa population, supporting the admixture hypothesis30. This suggests a potential Lawa contribution of N to Tak. The high N1a2 prevalence in Khuen (17.65%) represents another potential source. Therefore, NO1/N* in Tak likely reflects complex gene flow from multiple sources: Karen, Lawa, and Khuen. More comprehensive markers are needed for further investigation. The presence of N clade haplogroups in our Tak samples provides a reference for comparison with individuals lacking Thai citizenship. Shared haplogroups could provide genetic evidence supporting kinship claims with the established Tak population, particularly for minority groups like the Karen, Lawa, and Khuen, especially in the absence of traditional documentation.

Analysis of Y-STR diversity revealed a significantly lower GD at DYS391 in Tak (0.2208) compared to the global average (0.521)66 and the overall Thai population (0.4708). We observed similarly lower GD in Skaw (0.1660), Pwo (0.2821), and Padong (0.3273), all subgroups of the Karen ethnic tribe who reside in the north of Tak21. This hints at a potential relationship between the Tak and Karen populations. The observed disparity in haplotype diversity between Y-STRs and Y-SNPs in Tak and Ranong populations (Y-SNPs: Tak = 0.7317, Ranong = 0.8970; Y-STRs: Tak = 0.9987, Ranong = 0.9964) reflects the fundamental differences in mutation rates and evolutionary patterns of these markers. The higher Y-SNP haplotype diversity in Ranong suggests historical admixture, likely due to its role as a maritime trade hub facilitating interactions with diverse populations. Conversely, Tak’s inland location and relative isolation may account for its lower Y-SNP diversity. The elevated Y-STRs haplotype diversity in both regions indicates significant recent genetic variation. This highlights the importance of localized genetic databases for accurate comparisons when assessing potential kinship ties for stateless individuals.

We acknowledge that the geographical focus of our study on Tak and Ranong provinces limits its generalizability. The absence of Myanmar populations in comparative analyses, due to data unavailability, restricts insights into admixture, migration, and statelessness. To better support kinship claims and establish belonging for stateless individuals, future research should prioritize expanding sampling to Myanmar population and other regions to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of regional genetic diversity.

In summary, this study identifies distinct paternal genetic patterns in Tak and Ranong and their relevance to statelessness. We expand the Y-chromosome database of Thailand, enhancing tools for paternity testing and lineage tracing. Critically, our expanded Y-STR database provides a valuable resource for stateless individuals lacking documentation. The closely matching profiles can support their connection to established populations in Thailand and strengthen kinship claims relevant to citizenship rights. Shared genetic markers between stateless individuals and specific ethnic groups can further strengthen claims of belonging. The differentiation of Tak and Ranong underscores the need for localized genetic databases. Y-chromosome analysis should complement other evidence, with ethical considerations ensuring responsible genomic data usage.

Materials and methods

DNA samples

The selection of Tak and Ranong provinces was based on their demographic and geographic significance, particularly concerning stateless populations. Tak has a total population of 691,714, including 143,156 stateless individuals, making it the province with the second-largest stateless population in Thailand after Chiang Mai (162,084)67. As Chiang Mai was already extensively sampled in previous studies (Fig. 1), Tak was prioritized for this study. On the other hand, Ranong has a total population of 193,371, including 13,677 stateless individuals67. It is the southern province with the largest stateless population that was not previously sampled. To ensure proportional sampling, we considered the population sizes of these provinces. The total population ratio between Tak and Ranong is approximately 3.6:1 (691,714:193,371), and the stateless population ratio is approximately 10.5:1 (143,156:13,677). Accordingly, 327 unrelated Thai male participants holding Thai ID cards were recruited, with 274 from Tak and 53 from Ranong, resulting in a sampling ratio of approximately 5.2:1. The research project and all experimental protocols received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (IRB No. 0671/65), and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The informed consent was obtained from all participants before blood sample collection. Samples were stored on Whatman™ FTA™ cards (GE Healthcare, USA), and DNA was extracted and preserved at 4 °C for subsequent analysis.

Y-SNPs selection

The selection of SNP loci was guided by previous studies that identified haplogroups within clade O (O2a and O1b1) as predominant in various Thai populations21,25,44,68. Based on these findings, we selected 16 SNP markers specific to haplogroup O to ensure comprehensive coverage within this clade. Additionally, we included 4 SNP markers for detecting haplogroups related to South Asian ancestry, as suggested by our hypothesis regarding potential genetic contributions from South Asia. To validate and refine this initial selection, Y-STR data from 33 samples were analyzed using the YHRD database (https://yhrd.org). Utilizing Y-STRs data for preceding haplogroups is a strategic approach due to its cost-effectiveness, efficiency, and the well-established correlation between Y-STRs haplotypes and specific Y-SNPs-defined haplogroups. By employing Y-STRs data to guide Y-SNPs markers selection, the study balances broad initial screening and precise subhaplogroup identification, fostering reliable and detailed genetic insights. The final panel of 20 Y-SNP markers included 16 markers specific to subhaplogroup O (M145, RPS4Y711, M89, M9, M214, M175, M119, P31, M95, SRY465, M122, M324, P201, M159, M134, and M133) and 4 markers specific to subhaplogroup R (M173, M417, SRY10831.2, and M207). Figure 2 illustrates the phylogenetic relationships among these 20 Y-chromosomal binary polymorphisms.

Primer designation for PCR amplification and SBE

The primer design for PCR amplification and single base extension (SBE) adhered to established protocols. Details of the primers used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S7. For subhaplogroup O, 16 primers targeting specific SNPs (M145, RPS4Y711, M89, M9, M214, M175, M119, P31, M95, SRY465, M122, M324, P201, M159, M134, M133) were modified from Park et al.34. Subhaplogroup R primers (M173, M417, SRY10831.2, and M207) were sourced from previous studies69,70,71. These primers were classified into four multiplex PCR assays and rigorously tested for primer dimer formation using a multiple primer analyzer (ThermoFisher).

PCR amplification and purification of PCR products

PCR amplification was performed in a 25 µL reaction volume containing 1 punch of purified FTA card, 12.5 µL of AmpliTaq Gold® 360 Master Mix (ThermoFisher), and primers at optimized concentrations. Amplification was conducted on a GeneAmp™ PCR System 9700. The PCR protocol included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 11 min, followed by 33 cycles of 22 s at 94 °C, 1 min at 60 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C. The procedure concluded with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT (ThermoFisher) through incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by enzymatic inactivation at 80 °C for 15 min.

Purification of SBE and SBE products

The SBE reaction was performed in a final volume of 10 µL, comprising 1 µL of PCR product, 5 µL of SNaPshot™ Multiplex kit (ThermoFisher), and the appropriate concentration of SBE primers as specified in Supplementary Table S7. The reaction was conducted on the GeneAmp™ PCR System 9700 (ThermoFisher) under the following conditions: an initial step at 96 °C for 10 s, followed by 25 cycles of 50 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The SBE product was purified using SAP (ThermoFisher) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Y-SNPs genotyping and Y-Haplogroup estimation

Y-SNPs genotyping was performed by mixing 1 µL of the SBE product with 8.7 µL of Hi-Di™ Formamide (ThermoFisher) and 0.3 µL of the GeneScan™ 120 LIZ™ Size Standard (ThermoFisher). SNPs were detected using the 3500xL Genetic Analyzer (ThermoFisher) and analyzed with GeneMapper ID-X Software v1.6, applying an allele interpretation threshold of 150 relative fluorescent units (RFU). Mutations in each Y-SNPs were identified and used for haplogroup assignment with yHaplo v1.1.2, referencing the International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree 2019–2020 v15.73 (https://isogg.org/tree/index.html). To validate the Multiplex kit, we used control DNA templates to ensure reliable performance. These templates were tested to confirm the accuracy of SNP typing across all loci.

Validation of the multiplex kit

To ensure reliable performance, the Multiplex kit was validated using control DNA templates. These templates were tested to confirm the accuracy of SNP typing across all loci, ensuring consistent and reproducible results. Although a formal sensitivity test was not conducted, the high-quality DNA extracted from blood samples on FTA cards provided sufficient quantity and reliability for SNP typing, ensuring the robustness of the kit for our study samples.

Y-STR markers and genotyping protocols

Y-STR profiling was conducted using the ForenSeq™ DNA Signature Prep Kit (Verogen), a commercially available NGS-based kit designed for compatibility with the MiSeq FGx platform. All NGS data were analyzed using the Universal analysis software (Verogen), and the allele number of the Y-STR marker was obtained from the sample detail report. The reliability and performance of this kit have been validated in the Thai population26.

Statistical analysis of forensic and population genetics features

To investigate the paternal genetic relatedness between Tak, Ranong, and other Asian populations, we combined our dataset of 327 new samples (Supplementary Table S1) with 8,773 Y-haplogroup samples from previous studies. Supplementary Table S2 provides details of the 9,100 samples from 12 Asian countries. Haplogroup frequency distributions were calculated by simple counting and visualized through pie charts on maps (Fig. 3). We then subset the data to focus on Thailand, China, Taiwan, and India populations, resulting in a final dataset of 126 populations with 7,568 samples. To examine relationships within Thailand, we included 33 additional Thai populations. We also incorporated 8 Chinese populations, a crucial consideration to account for historical migrations from South China27,28, 80 Indian populations considering the observed South Asian admixture in specific Thai populations and mitochondrial haplogroup sharing22,29,30,32,49, and 3 Taiwanese populations due to Austronesian-speaking admixture in southern Thailand29. The Y-haplogroups were defined according to ISOGG hierarchy using 20 SNP markers, assigning individuals to haplogroups based on specific mutations. Fisher’s exact test was performed using “fisher.test” in R72 to assess the significance of differences in haplogroup distribution among Thai populations, with significance set at p < 0.05.

To ensure sample independence, which cannot be determined solely through interviews when recruiting, we removed samples with identical Y-STR profiles from each dataset. This is crucial for population genetic analyses like AMOVA and NMDS, which rely on diversity. By removing duplicates, we retained only one sample per unique Y-STR profile, preventing bias and ensuring that our analysis represents a diverse set of paternal lineages. AMOVA was then conducted using the “poppr.amova” function from the “poppr” package in R. The statistical significance of the observed variances was determined using the “randtest” function, with 99 permutations, to assess the deviation from what would be expected under the null hypothesis of no genetic differentiation73. NMDS was used to simplify multivariate genetic data, facilitating pattern recognition and interpretation. NMDS analysis was performed using the “metaMDS” function from the Vegan74 which utilized a genetic distance matrix calculated with the “dist.genpop” function from the “Adegenet” package75 and visualized with ggplot276. Y-STR markers with < 25% genotype information and samples with > 25% missing genotype information were excluded from the analysis. Allele frequencies and forensic statistical parameters, including GD, discrimination power (PD), match probability (PM), probability of exclusion (PE), and polymorphism information content (PIC), were calculated using an online software, STR Analysis for Forensics (STRAF)77. The haplotype diversity (h) was calculated according to the previously described method by Nei78. The Y-STRs data was used to estimate the Time TMRCA of each Y-SNPs haplogroup using the MODIFIED Y-Utility: Y-DNA Comparison Utility, FTDNA 111 Mode BETA79, assuming a generation time of 31 years and a mutation rate was set to McDonald Rates. Age estimates were not calculated for haplogroups with less than 10 individuals.

Y-STRs data was incorporated in our analysis. We compiled 25,858 Y-STR profiles, including published data and new samples from this study (Supplementary Table S8). We then subset this dataset to include 8,108 Y-STRs profiles from populations of interest across 13 Asian countries based on 10 shared Y-STR markers: DYS389I, DYS389II, DYS390, DYS391, DYS437, DYS438, DYS439, DYS448, YGATAH4, and DYS635 (Supplementary Table S6). A genetic distance matrix based on the sum of squared differences (Rst) was calculated using Arlequin. This Rst matrix was then used for NMDS analysis, following the same protocol applied to the Y-SNP data. The phylogenetic relationships among populations were constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method applied to the Rst genetic distance matrix. This analysis was performed with the “nj” function in the “ape” package in R, and the tree was visualized using Interactive Tree of Life v5 (iTOL). While Y-SNPs offer deep-rooted ancestry insights, Y-STRs provide a recent lineage differentiation with their higher mutation rate. This integrated approach enhances our understanding of the demographic history of the studied populations. Median-Joining (MJ) networks were constructed for the O1b1a1a and O2 clades using Y-STR haplotype data from this study and previous research on Thai populations. These networks were generated using NETWORK 10.2.0.0, focusing on the clades with the highest frequencies in the dataset. The MJ network revealed high diversity within these haplogroups, resulting in several overlapping reticulations. To address this, we applied the post-processing Maximum Parsimony (MP) calculation method available in the software. The reconstructed MJ networks for the O1b1a1a and O2 clades are presented in supplementary Fig. S4.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed in this study are provided in the supplementary files and have been deposited in publicly accessible repositories. The complete dataset, encompassing all samples, is available on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/14195042.

Change history

26 June 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08061-8

References

Premsirat, S., Deepadung, S., Suwannaket, E. & Choosri, I. Phaenthi Phasa Khong Kloom Chattiphan Tang Tang Nai Prathet Thai [Echnolinguistic Maps of Thailand] (Khurusapha, 2004).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). How Thailand’s Grassroots Organizations Are Working to End Statelessness. https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2022/11/6363e8c74/thailands-grassroots-organizations-working-end-statelessness.html#:~:text=Thailand%20has%20a%20registered%20stateless,from%20the%20mountainous%20border%20areas (2022).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons. (2023).

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Appeal 2024. https://reporting.unhcr.org/global-appeal-2024 (2024).

Kitchanapaibul, S. et al. Status of the stateless population in Thailand: How does stigma matter in their life? PLoS One 17 (2022).

Cheva-Isarakul, J. Contextualising statelessness: Contingent citizenship and the politics of (non)Recognition in Thailand. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia (2023) https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2023.7.

Phongsiri, M. & Thongyou, M. Thai Diaspora: What happens when they return ‘home’?. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 21, 59–69 (2012).

Sperfeldt, C. Statelessness and governance at the periphery. in Statelessness, Governance, and the Problem of Citizenship (eds. Bloom, T. & Kingston, L. N.) 196–209 (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2021). https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526156426.00026.

Cheva-Isarakul, J. & Sperfeldt, C. Citizenship and statelessness among mobile maritime populations: The case of the Moken in Thailand. Citizensh Stud 27, 530–547 (2023).

United Nations Development Programme. Seeking Opportunities Elsewhere: Exploring the Lives and Challenges of Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand. Bangkok. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-12/undp-mmr_seeking-opportunities-elsewhere_nov_2023_final.pdf (2023).

Yeo, S. S., Gagnon, T. & Thako, H. Schooling for a stateless nation: The predicament of education without consensus for Karen refugees on the Thailand-Myanmar border. Asian J. Peacebuilding 8, 29–55 (2020).

Flaim, A., Williams, L. B. & Ahlquist, D. B. How statelessness, citizenship, and out-migration contribute to stratification among rural elderly in the highlands of Thailand. Soc. Forces 99, 333–365 (2020).

Harris, J. Uneven inclusion: Consequences of universal healthcare in Thailand. Citizensh Stud 17, 111–127 (2013).

Travis, J. Scientists Decry isotope, DNA testing of ‘nationality’. Science 1979(326), 30–31 (2009).

Wagner, J. K., Madden, D., Oray, V. & Katsanis, S. H. Conversations surrounding the use of DNA tests in the family reunification of migrants separated at the United States-Mexico Border in 2018. Front. Genet. 10 (2019).

Katsanis, S. H. DNA in immigration and human trafficking. Forensic DNA Appl. 459–476 (2023).

Oray, V. & Katsanis, S. H. Ethical considerations for DNA testing as a proxy for nationality. Global Bioethics 32, 51–66 (2021).

Lee, C. & Voigt, T. H. DNA testing for family reunification and the limits of biological truth. Sci Technol Human Values 45, 430–454 (2020).

Balanovsky, O. Toward a consensus on SNP and STR mutation rates on the human Y-chromosome. Hum. Genet. vol. 136 575–590 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1805-8 (2017).

Köksal, Z. et al. Testing the Ion AmpliSeqTM HID Y-SNP Research Panel v1 for performance and resolution in admixed South Americans of haplogroup Q. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 59 (2022).

Kampuansai, J. et al. Paternal genetic history of the Yong population in northern Thailand revealed by Y-chromosomal haplotypes and haplogroups. Mol. Genet. Genomics 295, 579–589 (2020).

Woravatin, W. et al. South Asian maternal and paternal lineages in southern Thailand and the role of sex-biased admixture. PLoS One 18 (2023).

Brunelli, A. et al. Y chromosomal evidence on the origin of northern Thai people. PLoS One 12, (2017).

Kutanan, W. et al. Contrasting maternal and paternal genetic variation of hunter-gatherer groups in Thailand. Sci. Rep. 8 (2018).

Kutanan, W. et al. Contrasting paternal and maternal genetic histories of Thai and Lao populations. Mol Biol Evol 36, 1490–1506 (2019).

Sathirapatya, T., Sukawutthiya, P. & Vongpaisarnsin, K. Massively parallel sequencing of 24 Y-STR loci in Thai population. Forensic Sci Int Genet Suppl Ser 6, e310–e313 (2017).

McColl, H. et al. The prehistoric peopling of Southeast Asia. Science 1979(361), 88–92 (2018).

Lipson, M. et al. Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory. Science 1979(361), 92–95 (2018).

Changmai, P., Phongbunchoo, Y., Kočí, J. & Flegontov, P. Reanalyzing the genetic history of Kra-Dai speakers from Thailand and new insights into their genetic interactions beyond Mainland Southeast Asia. Sci. Rep. 13 (2023).

Changmai, P. et al. Indian genetic heritage in Southeast Asian populations. PLoS Genet 18 (2022).

Kutanan, W. et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of Thai and Lao populations indicate an ancient origin of Austroasiatic groups and demic diffusion in the spread of Tai-Kadai languages. Hum Genet 136, 85–98 (2017).

Jaisamut, K. et al. Unraveling the mitochondrial phylogenetic landscape of Thailand reveals complex admixture and demographic dynamics. Sci. Rep. 13 (2023).

Fondevila, M. et al. Forensic SNP genotyping with SNaPshot: technical considerations for the development and optimization of multiplexed SNP assays. Forensic Sci. Rev. 29, 57–76 (2017).

Park, M. J. et al. Y-SNP miniplexes for East Asian Y-chromosomal haplogroup determination in degraded DNA. Forensic Sci Int Genet 7, 75–81 (2013).

Blanco-Verea, A., Jaime, J. C., Brión, M. & Carracedo, A. Y-chromosome lineages in native South American population. Forensic Sci Int Genet 4, 187–193 (2010).

Geppert, M. et al. Identification of new SNPs in native South American populations by resequencing the y chromosome. Forensic Sci Int Genet 15, 111–114 (2015).

Inagaki, S. et al. Typing of Y chromosome single nucleotide polymorphisms in a Japanese population by a multiplexed single nucleotide primer extension reaction. Leg Med 4, 202–206 (2002).

Sanchez, J. J. et al. Multiplex PCR and minisequencing of SNPs: A model with 35 Y chromosome SNPs. Forensic Sci Int 137, 74–84 (2003).

Onofri, V. et al. Development of multiplex PCRs for evolutionary and forensic applications of 37 human Y chromosome SNPs. Forensic Sci Int 157, 23–35 (2006).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Preprint at http://qgis.org (2023).

Wang, C. C. & Li, H. Inferring human history in East Asia from Y chromosomes. Investigative Genetics vol. 4 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1186/2041-2223-4-11 (2013).

Cai, X. et al. Human migration through bottlenecks from Southeast Asia into East Asia during last glacial maximum revealed by Y chromosomes. PLoS One 6 (2011).

Yao, X. et al. Improved phylogenetic resolution for Y-chromosome Haplogroup O2a1c-002611. Sci. Rep. 7 (2017).

Trejaut, J. A. et al. Taiwan Y-chromosomal DNA variation and its relationship with Island Southeast Asia. BMC Genet. 15 (2014).

Chaubey, G. et al. Population genetic structure in indian austroasiatic speakers: The role of landscape barriers and sex-specific admixture. Mol Biol Evol 28, 1013–1024 (2011).

Tätte, K. et al. The genetic legacy of continental scale admixture in Indian Austroasiatic speakers. Sci. Rep. 9 (2019).

Changmai, P. et al. Ancient DNA from protohistoric period cambodia indicates that South Asians admixed with local populations as early as 1st–3rd centuries CE. Sci. Rep. 12 (2022).

Vongpaisarnsin, K., Listman, J. B., Malison, R. T. & Gelernter, J. Ancestry informative markers for distinguishing between Thai populations based on genome-wide association datasets. Leg Med 17, 245–250 (2015).

Kutanan, W. et al. Reconstructing the human genetic history of mainland Southeast Asia: Insights from genome-wide data from Thailand and Laos. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3459–3477 (2021).

Lo, Y. H. et al. Detecting genetic ancestry and adaptation in the Taiwanese Han people. Mol Biol Evol 38, 4149–4165 (2021).

Vongpaisarnsin, K., Saengkaeotrakul, P., Boonlert, A. & Tansrisawad, N. Gene and haplotype diversity of 23 Y-chromosomal short tandem repeat loci in the central Thai population. Forensic Sci Int Genet 14, 191–193 (2015).

Baker, C. & Phongpaichit, P. A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108120197.

Karafet, T. M. et al. New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree. Genome Res 18, 830–838 (2008).

Fu, Q. et al. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514, 445–449 (2014).

Fu, Q. et al. An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature 524, 216–219 (2015).

Seetaraso, T., Kutanan, W., Kampuansai, J., Muisuk, K. & Srikummool, M. Unique genetic structure of Y-chromosomal Lineage of the Moken from the Andaman Sea of Thailand. CMUJ. Nat. Sci. 19, 1066–1079 (2020).

Mahal, D. G. & Matsoukas, I. G. The geographic origins of ethnic groups in the indian subcontinent: Exploring ancient footprints with Y-DNA haplogroups. Front. Genet. 9 (2018).

Sharma, S. et al. The Indian origin of paternal haplogroup R1a1* substantiates the autochthonous origin of Brahmins and the caste system. J Hum Genet 54, 47–55 (2009).

Won-In, K. et al. Characterization on mosaic glass excavated from Phu Khao Thong (Ranong), Thailand. in Physics Procedia vol. 48 30–37 (Elsevier B.V., 2013).

Rootsi, S. et al. A counter-clockwise northern route of the Y-chromosome haplogroup N from Southeast Asia towards Europe. EJHG 15, 204–211 (2007).

Wang, F. et al. Genetic reconstruction and phylogenetic analysis by 193 Y-SNPs and 27 Y-STRs in a Chinese Yi ethnic group. Electrophoresis 42, 1480–1487 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Multiple Human Population Movements and Cultural Dispersal Events Shaped the Landscape of Chinese Paternal Heritage. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41, (2024).

Nahhas, R. W. Sociolinguistic Survey of Lawa in Thailand. (2011).

Kauffmann, H. E. Some social and religious institutions of the Lawa (Northwestern Thailand). J SIAM Soc 60, 237–306 (1972).

Kunstadter, P. Subsistence agricultural economies of Lua’ and Karen hill farmers, Mae Sariang District, Northwestern Thailand. in Farmers in the forest. (eds. Kunstadter, P., Chapman, E. & Sabhasri, S.) 118–208 (University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 1978).

Purps, J. et al. A global analysis of Y-chromosomal haplotype diversity for 23 STR loci. Forensic Sci Int Genet 12, 12–23 (2014).

The Bureau of Registration Administration (BORA), D. of P. A. M. of I. Population statistics. https://stat.bora.dopa.go.th/stat/statnew/statMenu/newStat/sumyear.php (2023).

Kutanan, W. et al. Cultural variation impacts paternal and maternal genetic lineages of the Hmong-Mien and Sino-Tibetan groups from Thailand. EJHG 28, 1563–1579 (2020).

Geppert, M. & Roewer, L. SNaPshot ® minisequencing analysis of multiple ancestry-informative Y-SNPs using capillary electrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol 830, 127–140 (2012).

Bouakaze, C., Keyser, C., Amory, S., Crubézy, E. & Ludes, B. First successful assay of Y-SNP typing by SNaPshot minisequencing on ancient DNA. Int J Legal Med 121, 493–499 (2007).

Underhill, P. A. et al. Separating the post-Glacial coancestry of European and Asian y chromosomes within haplogroup R1a. EJHG 18, 479–484 (2010).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Preprint at (2021).

Kamvar, Z. N., Tabima, J. F. & Gr̈unwald, N. J. Poppr: An R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partially clonal, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ 2014, 1–14 (2014).

Oksanen Jari et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. Preprint at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2022).

Jombart, T. & Bateman, A. adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008).

Wickham, H. ggplot2. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 3, 180–185 (2011).

Gouy, A. & Zieger, M. STRAF: A convenient online tool for STR data evaluation in forensic genetics. Forensic Sci Int Genet 30, 148–151 (2017).

Nei, M. Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70, 3321–3323 (1973).

McGee, MODIFIED Y-Utility: Y-DNA Comparison Utility, FTDNA 111 Mode BETA. https://dna.cfsna.net/HAP/Modified-yUtility.htm

Acknowledgements

This research project is supported by the Second Century Fund (C2F), Chulalongkorn University, and the Center of Excellence in Forensic Genetics, Department of Forensic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand. The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Mgr. Piya Changmai, Ph.D., for his invaluable advice and suggestions throughout this research. The author used Gemini and ChatGPT to improve the language and clarity of this manuscript. The author then reviewed and edited the content, taking full responsibility for the published article.

Funding

This research project is funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovationovation Fund Chulalongkorn University (Grant no: CU_FRB640001_01_30_6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J., K.R., R.P., and K.V. conceptualized and designed the study. K.R., R.P., and P.S. conducted sample collection and laboratory work. R.P., T.S., and W.W. contributed to library preparation and sequencing. K.J. performed data analysis, visualization, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. K.R. and H.N. conducted additional data analysis and visualization. K.V. supervised the study and contributed to data interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the order of the Figures. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaisamut, K., Rasmeepaisarn, K., Pitiwararom, R. et al. Paternal genetic landscape of contemporary Thai populations in the borderland provinces of Thailand and Myanmar. Sci Rep 15, 6300 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90398-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90398-1