Abstract

Mn-doped ZnO thin films with varying Mn concentrations were synthesized on glass substrates using the pneumatic spray technique. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis confirmed the substitution of Zn by Mn in the ZnO matrix. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) revealed characteristic spin-orbit energy states of Zn:2p and Mn:3d, indicating strong Mn-ZnO interactions. Microstructural analysis showed non-uniform extended lines and spherical grains, with decreasing grain size as Mn concentration increased. X-ray diffraction (XRD) confirmed a polycrystalline hexagonal structure, with experimentally determined lattice parameters a = 3.1453 Å, c = 5.1353 Å, in agreement with CASTEP calculations. Optical measurements indicated ~ 80% absorbance in the visible range, with a shift from blue to red as Mn content increased, suggesting bandgap modulation. These findings highlight the potential of Mn-doped ZnO films for tunable optoelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zinc oxide (ZnO) is an inorganic material belonging to the family of transparent conductive oxides (TCOs). Its abundance, non-toxicity, and high efficiency make it an ideal candidate for transparent electrical interfaces in solar cells. ZnO is widely preferred due to its wide band gap (~ 3.37 eV), high stability, and ease of synthesis. Mn doping introduces magnetic properties into ZnO, making it a promising material for spintronic devices and magnetic sensors. Additionally, Mn reduces the recombination rate of charge carriers, thereby enhancing ZnO’s performance in photocatalytic degradation and energy conversion applications. As a TCO, ZnO exhibits both electrical conductivity and optical transparency, with approximately 85% transparency in visible light, an optical band gap exceeding 3 eV, and controlled electrical conductivity. Various deposition techniques are employed for ZnO thin films doped with transition metals, including Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE), Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD), Pneumatic Spray Technique (PST), electrochemical deposition, and solid-state reaction methods. The ability of ZnO to alter its properties in response to environmental conditions makes it highly relevant for technological applications. Studies indicate that the electrical and optical properties of metal oxide thin films make them advantageous for photoelectronic devices, data storage, and catalytic applications1. ZnO, as an n-type direct band gap semiconductor, achieves high electronic transparency efficiency2. Researchers have shown particular interest in ZnO doped with 3d transition metals (Co, Ni, Mn, and Cu), which transforms it into a dilute magnetic semiconductor (DMS), making it a valuable material for spintronic applications3. Lu et al.4 reported that Co-doped ZnO films grown by MBE exhibit monocrystalline structures, improving their functional properties. Similarly, the PST method has been used to synthesize Co-doped ZnO films on glass substrates heated to 450 °C. Tietze et al.5 explored the magnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO thin films prepared via PLD. Bacaksiz et al.6 fabricated hexagonally shaped microrods of Co-doped ZnO films with varying doping concentrations (0, 1, 3, and 5%) using the PST method. Mn-doped ZnO thin films with different Mn concentrations (x = 0, 4, 6, 8, and 10%) were synthesized via PST, demonstrating the impact of doping on ZnO’s material properties. Additionally, R. Grothe et al.7 synthesized ZnO films deposited on ZnMgAl substrates using the Spray Coating Process (SCP), utilizing zinc acetate dihydrate (250 g/L) dissolved in ultra-pure water (0.055 µS/cm) for enhanced deposition efficiency. The Spray Pyrolysis Technique (SPT) has also proven effective for depositing thin oxide films on metal substrates within short processing times. Ag- and Au-doped ZnO films were successfully sprayed onto ultrasonically cleaned glass substrates, leading to improved electrical and optical properties8,9,10. Carbon-doped ZnO nanoparticles have been synthesized via the thermal decomposition of a zinc citrate precursor, forming 2D-ZnO nanoparticles with an optical band gap of 2.9 eV11. Al-doped ZnO films have been deposited on glass substrates using the sol-gel method, where all samples crystallized in a polycrystalline structure without impurity phases12. Recent studies have further explored ZnO’s potential in various applications. For instance, T.H. AlAbdulaal et al.13 demonstrated that doping ZnO with Y₂O₃ under visible light significantly enhances its photocatalytic performance for electronic and environmental applications. Silver nanowires-doped ZnO (ZnO: AgNWs) exhibited a higher figure of merit (688 × 10⁻⁶ m³), while aluminum-doped ZnO (ZnO: Al) also showed promising performance (295.4 × 10⁻⁶ m³), making both materials suitable for high-efficiency photovoltaic applications14. Ayana A et al.15 highlighted the critical role of deposition temperature in controlling the microstructural and piezoelectric properties of spray-pyrolyzed ZnO films on p-type silicon substrates. ZnO nanoparticles, synthesized by annealing zinc carbonate hydroxide precursors at four different temperatures (200, 400, 600, and 800 °C), were investigated for their morphology, structure, optical properties, and NO₂ gas-sensing performance. The incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles in gas sensors enhanced their response and selectivity to NO₂16,17. Li et al.18 demonstrated ZnO’s potential for lithium-ion battery electrodes, where its high surface area and conductivity contributed to improved charge/discharge cycles. ZnO, as a semiconductor, possesses a wide band gap, excellent chemical stability, and cost-effectiveness19. Nanostructured ZnO thin films deposited via a simple spray pyrolysis technique (SPT) on glass/FTO substrates at 450 °C exhibited crystalline nature with nano vial-like morphology20. ZnO’s hexagonal crystal structure, synthesized using a microwave-assisted method, led to the formation of ZnO micro flowers with an average size of 5 μm and a band gap of 3.19 eV21. Undoped and cadmium-doped ZnO (Cd-ZnO) thin films were deposited onto glass substrates via a cost-effective spray pyrolysis technique, where all films showed a preferred orientation along the (002) plane and exhibited a decreasing band gap with increasing Cd concentration22. The spray pyrolysis method was also employed to deposit quaternary material films by varying the substrate temperatures from 250 to 450 °C23. A series of ZnO and Mn-doped ZnO thin films were successfully deposited on cleaned glass substrates using the spray pyrolysis technique at different doping percentages (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 at%).

This work aims to investigate the influence of Mn doping on the structural, optical, and electrical properties of ZnO thin films to assess their potential for advanced applications in optoelectronics, spintronics, and magnetic sensors. By highlighting the impact of doping concentration on crystal structure, optical transmission, and electrical conductivity, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms affecting the performance of Mn-doped ZnO thin films. The findings will help guide the future development of ZnO-based devices optimized for photovoltaic, catalytic, and energy storage applications.

Experimental elaboration and characterization techniques

The spray pyrolysis technique was used to synthesize pure and Mn-doped ZnO thin films grown on cleaned glass substrates. The dimensions of the substrate are fixed at 2 × 2 cm2, and were cleaned before the deposition process with hydrochloric acid, ethanol, acetone, methanol and distilled water for 5 min. The drying of the glass substrate was done using a centrifuge. During the growth of ZnO and Mn-doped ZnO films, a solution of Zinc acetate dehydrate [Zn(CH3COO)2–2H2O] and manganese acetate tetrahydrate [Mn(CH3COO)2–4H2O] were usd as precursors and source of Mn2+ dopant ions. For pure ZnO sample, the precursor was dissolved in isopropanol [(CH3)2CHOH] and monoethanolamide [NH2CH2CH2OH] was added to the solution as stabilizer. Manganese acetate (0.2 M) solution was mixed into zinc acetate solution at various doping percentages with volume (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10%) and the deposited films are denoted by ZnO, Mn0.02Zn0.98O, Mn0.04Zn0.96O, Mn0.06Zn0.94O, Mn0.08Zn0.92O and Mn0.1Zn0.9O respectively. During the growth, the deposition time and speed were set at 10 min and 5 cm3/minute, the distance between the solution and the substrate was 5 cm in order to obtain transparent and uniform films. We note that the temperature substrate was maintained at 350 °C. X-ray diffraction spectra are obtained using a PAN analytical X’Pert (Philips) PRO MPD powder X-ray diffractometer equipped with an X’Celerator detector, which operates at a voltage of 45 kV and a current of 35 mA in the Bragg–Brentano geometry. The radiation used is the Cu-Kα line of wavelength λ = 0.154059 nm and the symmetrical scanning was carried out between 2θ = 20° and 2θ = 80°. Data were processed using X’Pert HighScore software. The optical transmission of the films was measured by a UV-Vis-Nir spectrometer in a wavelength range of 200 nm to 800 nm. FTIR spectra were recorded using a Shumadzu FTIR spectrometer from 1200 cm-1 to 400 cm-1. The morphology of the films was studied using, scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Results and discussion

Structure and morphology

Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was used to determine the composition of the manganese (Mn)-doped zinc oxide (ZnO) samples. EDX shows that the samples are quasi-stoichiometrFig. ure 1 depicts the typical Energy-Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis spectra of Mn0.02Zn0.98O thin films deposited by PST at 350 °C in air. The deposited sample is composed of O, Mn and Zn, where the Mn ion replaces Zn ion in ZnO matrix. This substitution influences the electrical and optical properties. The data revealed a slight variation in the ratios with increasing manganese concentration. We note that a slight decrease in the zinc content as the manganese concentration increased. The weight% of oxygen remained relatively stable across the sample, indicating that the addition of manganese had no significant effect on the oxygen content. The stability of the oxygen ratio preserves the crystal structure of ZnO, where oxygen is a primary lattice element, despite changes in other elemental compositions. The gradual increase in the manganese content reflects the strong interaction between Mn and ZnO and enhances the chemical properties and catalytic activity of the sample. Sample with higher manganese content show improved electrical conductivity. The spin-orbit coupling means that the Zn-2p peak splits into Zn:2p (3/2) and Zn:2p (1/2) peaks in the EDX spectrum. The EDX spectrum of Mn-3d exhibits two peaks connected to the J = 5/2 and 3/2 spin-orbit coupled energy states. For Mn0.02Zn0.98O films, the Mn:3d (5/2) and Mn:3d (3/2) appear at 5.8 keV and 6.5 keV with binding energy difference of 700 eV.

Figure 2 shows an Electronic Scanning Microscope (SEM) micrograph of the ZnO (a), Mn0.02Zn0.98O (b), Mn0.04Zn0.96O (c), Mn0.06Zn0.94O (d), Mn0.08Zn0.92O (e) and Mn0.1Zn0.9O (f) thin films at x 20000 magnification. The morphology of Mn-doped ZnO confirmed the low aggregation, better distribution and spherical nanocrystallites. The hexagonal wurtzite crystal structure was achieved for Mn-doped ZnO nanomaterials. EDAX analysis of the nanoparticles was consistent with the formation of Mn doped ZnO. We study the evolution of the surface microstructure as a function of the Mn/Zn ratio (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10%). We clearly observe on the micrograph different atomic rearrangements surrounded by the manganese nanoparticles. The formation of Mn–ZnO nanocomposites were confirmed by EDX. It is observed that the surface of ZnO thin film is homogeneously covered by the agglomerated grains, where the size is 15 nm. Furthermore, we note that each agglomeration is made up of small spherical grains of 15 nm. It has been observed that when the Mn doping concentration increases, the crystallite size of ZnO and Mn-doped nanoparticles produced using the sol–gel auto combustion process drops from 38.42 to 27.54 nm24.

An AFM image describes the topography of a sample surface and generates a topographic map of the surface features. Figure 3 shows the AFM images of ZnO, Mn0.02Zn0.98O, Mn0.04Zn0.96O, Mn0.06Zn0.94O, Mn0.08Zn0.92O and Mn0.1Zn0.9O. The samples consist of non-uniform extended lines with heights between 3 nm and 40 nm and widths between 5 nm and 60 nm and spherical grains, where the size decreases as the Mn concentration increases. The development of ZnO was done using a pure material, but the growth was obtained in several orientations. We note that the preferential orientation is (002). X-Ray powder diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed using Cu-Kα (λ = 0.154059 nm). Bragg’s law relates the reticular distance between atoms of a crystal and the angle θ at which waves sent to the crystal are diffracted following the [hkl] direction:

n, θ and\(\lambda\) are the diffraction order, the diffraction angle and the wave length.

The lattice parameters are calculated according to the direction [hkl]\(\theta\) by the relation25:

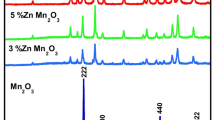

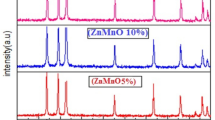

The study of (XRD) identifies the structural changes of thin films ZnO, Mn0.02Zn0.98O, Mn0.04Zn0.96O, Mn0.06Zn0.94O, Mn0.08Zn0.92O and Mn0.1Zn0.9O. The synthesized samples exhibit a polycrystalline nature with hexagonal crystal structure as shown in Fig. 4. The XRD patterns of the films show peaks corresponding to (1 0 0), (0 0 2), (1 0 1), (1 0 2), (1 0 3), (1 1 2) and (0 0 4) planes in the hexagonal ZnO structure. The (002) peak position of ZnO doped Mn concentration ≥1% is closer to that of ZnO powder 34.426°26, this value is in good agreement with our value 34.672 °. When the Mn dopant fraction rises to 6%, the (002) peak’s intensity falls and its nit grows. This indicates that the crystallinity is deteriorating because to the stresses introduced by the difference in ionic radii between Mn and Zn. Careful XRD analysis reveals that the lattice characteristics of Mn-doped ZnO thin films have somewhat changed, and the peak’s position has shifted towards the higher 2θ values. For every sample, the peaks unmistakably display a hexagonal wurtzite structure. The doping of Mn into ZnO samples is confirmed by a negligible shift in the first three peaks of the doped samples when compared to pure ZnO. Since there is no additional peak in any of the patterns, doping has no influence on the structure of ZnO. Additionally, the dopant Mn is evenly distributed throughout the whole surface of ZnO, confirming that there are no impurities present in the crystal. The intensity of peaks do not show a linear relationship with the increasing Mn concentration. This can be attributed to several factors such as saturation doping (8 or 10%), where the incorporated Mn atoms are not in regular manner. The ionic radius difference between Zn²⁺ and Mn²⁺ introduces internal lattice strain as Mn concentration increases, affecting the intensity peaks. We also studied theoretically the effect of doping with Mn on the lattice parameters as clarified in the Fig. 5. It is reported that our lattice parameters a and c increase linearly with the increase in the amount of Mn doping. Our values of the lattice parameters for undoped ZnO are \(a=3.1453\) Å and\(c=5.1353\) Å deduced experimentally from x-ray diffraction pattern are in good agreement with those calculated theoretically\(a=3.275\) Å and \(a=5.283\) Å. X-ray diffraction revealed that the cell parameters, a and c, increased with the increase in Mn content27. The morphological structure of Mn-ZnO NPs described using TEM images revealed that the sizes of the produced particles were in the range of 20–80 nm28. The XRD pattern shows only the peaks correspond to the wurtzite crystal structure of ZnO29.

Electronic properties

The structure of the bands is a determining spectrum for a material in its application in the photovoltaic field as an absorber, which is related to the band gap. This band gap must be estimated with precision, hence the use of the GGA-mBJ potential, which gives a value closer to the experimental one30,31. The band structures of ZnO, ZnO0.99Mn0.01 and ZnO0.90Mn0.10 for an equilibrium experimental lattice constant are shown in Fig. 6. For ZnO and ZnO0.99Mn0.01, there are no bands around the Fermi level in the first conduction band, suggesting their direct Г- Г band gap semiconductor, while ZnO0.90Mn0.10 shows a metallic character. Figure 5 shows that the lattice parameters a and c increase with increasing Mn concentration. While, Fig. 6 depicts that band gap decreases with increasing Mn concentration. Consequently, the band gap is inversely proportional to the lattice parameters. We visualize in Fig. 7 the effect of doping with Mn impurities on the band gap. We practically see a linear decrease of band gap with the increase in doping up to 8% and it becomes metal.

Figure 8 shows the effect of doping with Mn impurities on the band gap in the Brillouin zone. The effect is more important for Mn doping in the range 0 to 4%, especially at Г point. The direct band gap is less sensitive to concentrations located between 5 and 10%. When the composition increases, the band gap decreases up to 8% and it becomes metal. We compute the total and partial densities of states as a function of energy for undoped ZnO in order to understand the band structure, as shown in Fig. 9. The upper valence band consists of Zn: d and O: p. The zero value of electronic total density of states (TDOS) at the Fermi level confirms the semiconducting behavior of ZnO. ZnO is a semiconductor, the nature of the compound and the band gap are affected by the electrons in the d orbital of the Mn dopant as shown in Fig. 10.

We see that the concentration of Mn has no effect on the intensity of the peaks and their corresponding energies below the Fermi level and in the first conduction band which extends up to 2.5 eV. The intensity of the peaks of the Mn: d orbitals and their energy positions affect the conduction bands located beyond 5 eV. The concentration of the Mn dopant increases the intensity of the peaks, which shift towards low energies, resulting in a reduction of the band gap.

Optical properties and transmission measurements

Transmission measurements in thin films are important in the field of electroniFig. ig. 11 shows a schematic view of the optical transmission as a function of wave length for various Mn content. It measures the amount of light that passes through a material. Light scatters and attenuates due to the high absorption of the material. The optical transmission exhibits resonance peak, which is shifted toward the lower wave length when the percentage of Mn doping increases. It is reported that the resonance peak will have a redshift due to the fact that the wavelength of the photons and the percentage of Mn doping increase. Optical performance is linked to the absorption of multiphonons at high wavelengths. Photons with sufficient energy are absorbed by excited electrons across the band gap. ZnO films doped Mn are highly transparent in the visible range with an average transmittance value located between 84 and 95%.

Using the following formula, the transmittance T and the film thickness provide the absorption coefficients of ZnO doped Mn films32:

And

where\(hv\) is the incidence photon energy, \({E_g}\) is the band gap energy, and A is a constant33. A plot of\({\left( {\alpha hv} \right)^2}\) against \(hv\) is made to determine\({E_g}\) using the linear fit. The detailed fitting process is shown in Fig. 12, for various Mn content. It is reported that \({\left( {\alpha hv} \right)^2}\) increases with the increase in hv and this increase is not very sensitive for lower values of hv. The effect of Mn doping on \({\left( {\alpha hv} \right)^2}\) is not uniform. The optical band gap (Eg) is estimated by taking the origin of the extrapolation at zero absorption with the photon energy axis, that is to say\({\left( {\alpha hv} \right)^2}\) 0.

The excitonic absorption peak changes towards the lower wavelength side with the Mn-doped ZnO nanoparticles, according to the absorbance spectra displayed in Fig. 13. Undoped ZnO’s PL spectra show wide visible emission at 560 nm and UV emission at 388 nm, both of which have different relative peak intensities.

Figure 14 shows the effect of percentage Mn doping on optical band gap (Eg). The estimated band gap value of ZnO is 3.271 eV which is in agreement with the reported value 3.3 eV cited by V. Srikant and D. R. Clarke at room temperature34.

The incorporation of Manganese improves the crystallinity of ZnO films. The optical band gap value decreases from 3.22 eV to 3.15 eV when the average grain size decreases from (76 ± 1) nm to (25 ± 05) nm35. Analysis of the absorption limit indicates that the optical band gap is 3.20 to 3.21 eV and the electronic transition is direct36. A plot of \({\left( {\alpha hv} \right)^2}\) against \(hv\) is made to determine\({E_g}\) using the linear fit (Fig. 12). The \({E_g}\)is derived from the cross point at the \(hv\)-axis with the tangent to (alphv)2. We have calculated the band gap of these sample from linear fitting to the\({\left( {\alpha hv} \right)^2}\) against energy \(hv\) plot and the value of band gap obtained are between 3.18 and 3.25 eV which is slightly lower in generally reported value 3.4 eV37. The native n-type ZnO semiconductor doped with Mn impurities acts as a donor by substituting Zn. Excess electrons ionized by impurities that fill the minimum conduction band of ZnO. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy provide information about the molecular interactions and structural changes induced by the incorporation of Mn into the ZnO matrix. Figure 15 illustrates the Normalized absorbance as a function of the wave number for various Mn doping concentrations in the wave number range of 500 to 4000 cm⁻¹. Various peaks characteristic of specific vibrational modes within the ZnO matrix and at the sites where the Mn atoms are doped. The primary peaks are observed at low frequencies (500 to 600 cm⁻¹) which correspond to the fundamental stretching and bending vibrations of the Zn–O bond. Upon incorporation of Mn into the ZnO matrix, it alters the local bonding environment of Zn–O and slight changes are noted in the position and intensity of these peaks. The increase in Mn concentration shifts peaks toward lower wave numbers, suggesting a weakening of the Zn–O bond or a change in the bond length due to the introduction of Mn. This behavior reflects the structural distortions and interactions induced by the dopants. The bending vibrations of the O–Zn–O linkages is observed in the range 1300 to 1500 cm⁻¹. These vibrations provide insight into the symmetry of the ZnO crystal structure. The broadening of peaks suggests that Mn atoms introduce local structural changes, which influence the lattice dynamics and affect the vibrational behavior of the O–Zn–O bonds. In the higher frequency range of 2000–4000 cm⁻¹, the FTIR spectra show bands related to the stretching vibrations.

Conclusion

Mn-doped ZnO thin films were analyzed using UV-visible spectrophotometry, atomic force microscopy, and X-ray diffraction. The lattice parameters increase linearly with doping concentration. The band gap decreases progressively with increasing Mn content, reaching a metallic state at 80% doping. ZnO and ZnO0.99Mn0.01 exhibit a direct (Г-Г) band gap, while ZnO0.90Mn0.1 shows metallic behavior. The effect of Mn doping on the band gap is more pronounced between 0 and 4%, particularly at the Г point. For concentrations between 5 and 10%, the impact becomes less significant. The band gap reduction is attributed to the interaction of Mn d-orbital electrons. The Mn concentration does not affect the upper valence band below the Fermi level. Mn-doped ZnO exhibits strong optical transmission. However, excessive doping reduces its photoluminescence.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Tarwal, N. L. et al. Growth of multifunctional ZnO thin films by spray pyrolysis technique. Sens. Actuators Phys. 199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2013.05.003 (2013).

Wager, J. F. Transparent Electronics. Science 300, 1245, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1085276 (2003).

Lu, Z. L. et al. The origins of ferromagnetism in Co-doped ZnO single crystalline films: from bound magnetic Polaron to free carrier-mediated exchange interaction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3224911 (2009).

Tarwal, N. L. et al. Structure, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and photoluminescence investigations of the spray deposited Cobalt doped ZnO thin films. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 106, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3224911 (2014).

Tietze, T. et al. XMCD studies on Co and Li doped ZnO magnetic semiconductors. New. J. Phys. 10. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/10/5/055009 (2008).

Bacaksiz, E. et al. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Zn1–xCoxO thin films prepared by spray pyrolysis. Thin Solid Films 516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsf.2008.03.042 (2008).

Grothe, R. et al. Spray pyrolysis of thin adhesion-promoting ZnO films on ZnMgAl coated steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2020.125869 (2020).

N. L. Tarwal, V. L. Patil, J. R. Rani, K. V. Gurav, J. S. Shaikh, M. S. Khandekar, N. S. Harale, P. S. Patil, J. H. Jang, Plasmonic DSSC performance of spray deposited Ag-ZnO and Au-ZnO films. Chin. J. of Phys. 73, 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjph.2021.03.031 (2021).

Y. Bouznit, A. Henni, Enhanced photoelectrochemical performance of Al-doped ZnO thin films prepared by co-spray technique. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 118, 1052088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2020.105208 (2020).

Bharat, T. C. et al. Synthesis of doped zinc oxide nanoparticles: A review. Mater. Today: Proc. 11, 767–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.03.041 (2019).

Hosni, N. M., gomaa, I., Elmahgary, M. G. & Ibrahim, M. A. ZnO doped C: facile synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic degradation of dyes. Sci. Rep. 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41106-4 (2023).

Munawaroh, H., Wahyuningsih, S. & Ramelan, A. H. Synthesis and characterization of al doped ZnO (AZO) by Sol-gel method. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 176, 012049. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/176/1/012049 (2017).

AlAbdulaal, T. H., AlShadidi, M., Hussien, M. S. A., Bouzidi, A. & Yahia, I. S. Enhancement of the photocatalytic performance of Y2O3–ZnO nanocomposites under visible light: towards multifunctional materials for electronic and environmental applications. Opt. Mater. 139, 113751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2023.113751 (2023).

Kumar, D., Stoichkov, V., Brousseau, E., Smith, G. C. & Kettle, J. Correction: high performing AgNW transparent conducting electrodes with a sheet resistance of 2.5 Ω Sq–1 based upon a roll-to-roll compatible post-processing technique. Nanoscale 11 (12), 5771. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NR90049G (2019).

Ayana, A., Fei, H., Jan, S., Rajendra, B. V. & Pankaj, S. Microstructural and piezoelectric properties of ZnO films. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 146https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2022.106680 (2022).

Fan, F. et al. Synthesis and gas sensing properties to NO2 of ZnO nanoparticles, Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 185, 377–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2013.05.020 (2013).

Kumar, D., Singh, M., Kushwaha, M., Makarana, G. & Yadav, M. R. Integrated use of organic and inorganic nutrient sources influences the nutrient content, uptake and nutrient use efficiencies of fodder Oats (Avena sativa). Indian J. Agron. 66 (4), 466–473 (2021).

Li, H. et al. A male germ-cell-specific ribosome controls male fertility. Nature 612, 725–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05508-0 (2022).

Wei, T. et al. Nanosized zinc oxides-based materials for electrochemical energy storage and conversion: batteries and supercapacitors. Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2), 714–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.06.037 (2022).

Tarwl, N. L. et al. Spray deposition of the nanostructured ZnO thin films for non-volatile resistive switching memory applications. Appl. Phys. A. 129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00339-022-06253-x (2023).

Pawar, S. S., Redekar, R. S. & Tarwal, N. L. Exploring the photocatalytic activity of surfactant-free ZnO micro-flowers synthesized by microwave-assisted method. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112106 (2024).

Tarwal, N. L. et al. Gas sensing performance of the spray deposited Cd-ZnO thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 598, 282–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.01.200 (2014).

Patil, K. V. et al. Effect of substrate temperature on the properties of spray-deposited Cu2NiSnS4 films. Mater. Lett. 357, 135689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2023.135689 (2024).

Kanwal, S. et al. Room-Temperature ferromagnetism in Mn-Doped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by the Sol–Gel method. ACS Omega. 8 (31), 28749. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c03418 (2023).

Epelboin, Y. Andre Authier (1932–2023). Acta Cryst. A 79. https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053273323005120 (2023).

Ahmed, S. A. Structural, optical, and magnetic properties of Mn-doped ZnO samples. Results Phys. 7, 604–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2017.01.018 (2017).

Zahid, A. et al. Synthesis of Mn-Doped ZnO nanoparticles and their application in the transesterification of Castor oil. Catalysts 13 (1), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13010105 (2023).

Otadi, M., Shayegh, Z. P. & Monajjemi, M. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 115, 12471–12482, https://doi.org/10.33263/BRIAC115.1247112482 (2021).

Guomei, T., Hua, L. & Wei, Z. The variation of optical band gap for ZnO:In films prepared by sol-gel technique. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/348601 (2013).

Vijayaprasath, G. et al. Role of nickel doping on structural, optical, magnetic properties and antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Bull. 76, 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2015.11.053 (2016).

Yassin, O. A. Electronic and optical properties of Zn. Optik 127, 1817–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2015.11.073 (2016).

Pancove, J. I. & Work, N. Optical Processes in Semiconductors, Dover Publication, Inc., (Unabridged republication of the work originally published by Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1971). (1975).

Tauc, J., Grigorvici, R. & Vancu, A. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Germanium. Physica Status Solidi (b) 15, 627-637. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.19660150224 (1966).

Srikant, V. & Clarke, D. R. On the optical band gap of zinc oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 83, 5447–5451. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.367375 (1998).

Dutta, S. et al. Defects and the optical absorption in nanocrystalline ZnO. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 19 (23), 236218. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/19/23/236218 (2007).

Natsume, Y. & Sakata, H. Zinc oxide films prepared by sol-gel spin-coating. Thin Solid Films. 372https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6090(00)01056-7 (2000).

Look, D. C. Recent advances in ZnO materials and devices. Mat. Sci. Eng. B. 80, 383–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5107(00)00604-8 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-208).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: (A) Rahal, I. Bouchama Data curation: M.A. Ghebouli Formal analysis: (B) Ghebouli, M. FatmiMethodology: T. Chihi, Talal M. AlthagafiValidation: Faisal Katib AlanaziVisualization: Khatir Khettab.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahal, A., Bouchama, I., Ghebouli, M.A. et al. Experimental investigation of structural and optical properties of Mn-doped ZnO thin films deposited by pneumatic spray technique. Sci Rep 15, 7086 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90425-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90425-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A comparative study on the effect of thickness in sol–gel deposited ZnO, SnO₂, and TiO₂ thin films and their photocatalytic performance in methylene blue decolorization

Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology (2026)

-

Biogenic Zinc nanoparticles: green approach to synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial applications

Microbial Cell Factories (2025)

-

Investigation of structural elastic electronic optical and thermoelectric properties of LiInS₂ and LiInTe₂ for optoelectronic and energy conversion

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Tuning the band gap and metallic phase via Ni/Mn co-doping of Zn0.8Ni0.20-xMnxO nanoparticles

Applied Physics A (2025)