Abstract

Dementia rates are projected to increase significantly by 2050, posing considerable challenges for healthcare systems worldwide. Developing efficient diagnostic tools is critical, and machine learning (ML) algorithms have shown potential for improving the accuracy of cognitive impairment classification. This study aims to address challenges in current systems by leveraging readily available electronic medical record (EMR) data to simplify and enhance the classification of cognitive impairment. The analysis includes 283 older adults, categorized into three groups: 144 individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 38 with dementia, and 101 healthy controls. Various ML techniques are evaluated to classify cognitive performance levels based on input features such as sociodemographic variables, lab results, comorbidities, Body Mass Index (BMI), and functional scales. Key predictors for distinguishing healthy controls from individuals with MCI are identified. These are history of myocardial infarction, vitamin D3 levels, the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale, age, and sodium levels. The nonlinear Support Vector Machine (SVM) with a Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel achieve the best performance for MCI classification, with an accuracy of 69%, an AUC of 0.75, and a Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.43. For distinguishing healthy controls from those with dementia, the most influential factors include the IADL scale, the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale, education, vitamin D3 levels, and age. Here, the Random Forest algorithm demonstrates superior performance, achieving 84% accuracy, an AUC of 0.96, and an MCC of 0.71. These two models consistently outperform other ML techniques, such as K-Nearest Neighbors, Multi-Layer Perceptron, linear SVM, Naive Bayes, Quadratic Discriminant Analysis, Linear Discriminant Analysis, AdaBoost, and Gaussian Process Classifiers. The findings suggest that EMR data can be an effective resource for the initial classification of cognitive impairments. Integrating these ML-driven approaches into primary care settings may facilitate the early identification of older patients who could benefit from further cognitive assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The number of people with dementia is expected to increase significantly as the global population ages1,2, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) being the most common cause3. The term Alzheimer’s disease (AD) refers to the presence of beta-amyloid (A\(\beta\)) plaques and pathological tau deposits, marking different stages within the larger continuum of Alzheimer’s, including the early and late phases of the disease4. Cognitive staging divides this continuum into cognitively unimpaired, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia, with dementia further classified into mild, moderate, and severe stages4. Although biomarkers are effective in diagnosing AD before the onset of clinical symptoms, due to their advanced nature and specialized measurement methods, they are not always available in primary care settings 5. Several factors have been recognized as important in identifying patients at the highest risk of developing AD, including lower Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores, higher Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) scores, the presence of an APOE4 allele (Apolipoprotein E epsilon 4), white matter hyperintensities, entorhinal cortex atrophy, higher tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), difficulties with complex daily activities as measured by Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), and female sex, all of which are becoming increasingly important indicators in clinical practice6.

The growing interest in machine learning (ML) algorithms stems from their significant advantages over traditional statistical analysis, particularly when dealing with highly complex data7,8,9. ML can be adapted to enhance accuracy in assessing cognitive performance5,7. Key areas where ML is applied in AD research include: (1) identification of the disease, (2) determination of disease subtypes, (3) prediction of disease progression, (4) discovery of biomarkers, and (5) exploration of new drug applications8,9,10,11. The growing reliance on electronic medical records (EMRs) presents new opportunities for population-level studies exploring disease progression and its causative factors7,12,13. EMRs are digital records that capture a patient’s medical history, diagnoses, treatments, and healthcare data, providing dynamic multidimensional information that makes them a valuable resource for various studies14. Current research often overlooks the secondary use of non-imaging clinical data, such as routinely collected EMR-derived information, despite its potential as a rich, low-cost, and noninvasive resource for identifying dementia risk factors. Instead, the focus has tended to be on more expensive imaging and diagnostic test data for ML-based analyzes9,15. Many established risk factors for AD, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, are already routinely documented in patients’ EMRs2,16,17.

Related work

In the literature, EMRs are highlighted as the primary data source for ML models7. Studies examine various categories of input variables8, including demographic data13,18,19,20; clinical variables21,22,23,24; lifestyle variables18,21,25; neuroimaging data (particularly structural magnetic resonance imaging - MRI)23,26; and genetic factors (primarily APOE4)18,19,23,27. Some research using ML include only neuroimaging in the input data28,29, as its inclusion generally yields better prediction results10. It should be noted that in clinical practice, neuroimaging procedures are usually reserved for patients who already exhibit clinical symptoms or are at high risk. Although brain abnormalities are often identified in patients, these findings are not always effective in diagnosing or predicting the disease at the individual level30. ML models are increasingly relying on easily accessible variables, such as data from questionnaires, physical assessments, and blood tests11,18. Other studies also use variables such as the results of the cognitive function test19,26.

ML classifiers used in AD research include classic models like Logistic Regression (LR)31, Random Forest (RF)19,20,32, Naive Bayes25, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)33, Support Vector Machine (SVM)26,33, and more advanced algorithms, such as Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)23,29, Residual Neural Network (RNN)28, Conditional Restricted Boltzmann Machine27, Gradient Boosted Trees22. Hybrid models that combine deep learning (DL) and classical ML methods are also employed23,34.

The most commonly reported performance indicator for ML algorithms in the systematic review was the area under the curve (AUC), with values ranging from 0.69 to 0.98, and major neurocognitive impairment, dementia, and AD being the most frequently studied conditions7. Another systematic review highlighted that the model accuracies (ACC) for classifying AD patients versus healthy controls ranged from 77.0% to 96.8%, depending on the specific models and input variables used35.

In the literature, ML models are primarily applied to prediction and classification tasks. Most of the research focuses on predicting the progression of AD using publicly available standardized multimodal datasets that combine neuroimaging with non-imaging clinical data10,15. Although classification does not directly predict disease progression, it allows disease detection8,11 and facilitates cross-sectional data analysis by accurately identifying individuals who may require further monitoring (MCI) or treatment (dementia), offering significant value in clinical practice. Using easily accessible data, such as demographic and clinical information, ML models can support early detection and timely interventions15,20. Classification models may be useful in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where dementia often remains underdiagnosed due to limited longitudinal data and unclear prevalence5.

Many studies demonstrate the practical application of ML models in AD classification with varied approaches and results. For example, El-Sappagh et al.19 achieved a multiclass classification accuracy of 93.95% in detecting AD using an RF model trained on cognitive scores, neuropsychological battery results, and genetic data. Akramifard et al.36 achieved 95.57% accuracy and 0.96 AUC to distinguish AD from controls and 78.67% accuracy with 0.79 AUC for MCI versus controls, using SVM to classify multimodal data such as MMSE, positron emission tomography (PET), CSF, personal information and MRI. Alatrany et al.33 identified key features of scales such as the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ), Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), as well as demographic factors. The classification performance varied between tasks, with normal controls vs. AD showing higher ACC values (RF: 97.5%, SVM: 97.3%, KNN: 96.4%, Naive Bayes: 96.1%) compared to normal controls vs. MCI (RF: 88.1%, SVM: 88.1%, KNN: 87.5%, Naive Bayes: 82.9%). Vichanin et al.26 used SVM to classify AD subjects, reporting a highest accuracy of 62.64% with only hippocampal volume and 83–90% with neuropsychological assessments.

Motivation and research contributions

Many contemporary ML models utilize complex variables, such as neuroimaging23 or specialized neuropsychological assessments11,19,26, which are often inaccessible to most healthcare providers. Additionally, numerous studies draw data from specialized research repositories like the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI)15,35. In contrast, data from hospitals and memory clinics often exhibit greater variability in quality due to less standardized protocols compared to those used in research settings10,15,35. Numerous studies use single datasets with cross-validation to assess the performance of ML models. However, due to generalization challenges with unseen data, accuracy tends to drop when tested on other research datasets, and even more so when applied to clinical data9.

The aim of this study is to develop practical ML models for identifying cognitive impairments, including MCI and dementia, by utilizing only readily available clinical data from EMRs. The dataset includes sociodemographic variables, comorbidities, laboratory test values, lifestyle factors, and functional scales, excluding additional sources such as neuroimaging or genetic data.

Considering the demonstrated utility of cognitive screening tests and neuropsychological assessments in classifying dementia patients in previous studies19,26,36, this research utilizes the results of cognitive screening tests to generate output labels for the ML models. While recognizing the limitations of screening tests in detecting cognitive impairment in older patients37,38, the proposed models offer an initial ’cognitive screening’ that can be conducted at the primary care level, helping to identify patients for further, more specialized evaluations. Screening tests are one of the methods supporting clinical diagnostic decisions; however, including them as input variables may cause the model to ’learn’ outcomes based on variables that already contain significant diagnostic information, potentially distorting the learning process and leading to biased results, especially in classification tasks. In addition, screening test results are not always available.

Furthermore, the literature reveals that while dementia is the most frequently studied condition, MCI has received considerably less attention7,10. To address this gap, this retrospective analysis places a stronger emphasis on MCI. This study investigates three classification scenarios for older patients with cognitive impairment using EMRs:

-

1.

MCI versus control group,

-

2.

Dementia versus control group,

-

3.

Combined group (MCI + dementia) versus control group (similar combinations have been explored in other studies39).

The primary objective of this research is to evaluate the classification performance of simple, data-efficient ML algorithms. Although more complex DL models provide greater generalization capabilities, they often require large datasets to achieve optimal performance7,10,22, which limits their applicability in smaller research centers and hospital units. To address this limitation, we conducted a comparative analysis of various classical ML algorithms to identify the most suitable approach for our specific problem. Such comparative assessments are frequently proposed in ML studies33,40.

To summarize, the main contributions of our research include:

-

Leveraging readily accessible EMRs data from routine medical practice,

-

Placing greater emphasis on the diagnosis of MCI, a condition studied less frequently than dementia,

-

The use of simple, data-efficient ML algorithms that do not require large input datasets.

Results

Sample characteristics

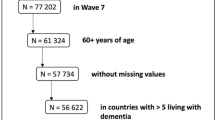

The data utilized in this study comprise 283 patients hospitalized at the John Paul II Geriatric Hospital in Katowice (Poland) between 2015 and 2019. These hospitalizations were performed as part of a comprehensive geriatric evaluation. All participants were assigned to one of three groups:

-

Control (C) (\(n=101\)),

-

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (\(n=144\); amnestic MCI single domain or amnestic MCI multiple domain,41),

-

Dementia (D) (\(n=38\), includes \(n=36\) (mild dementia) and \(n=2\) (moderate dementia),

Based on medical diagnoses and cognitive deficit profiles obtained by screening tests, 27 patients in the study group were identified with AD, 6 with vascular dementia, 2 with mixed dementia (atypical or mixed with AD) and 3 with unspecified dementia. However, due to the absence of comprehensive neuropsychological assessments and neuroimaging in this study, these classifications should be interpreted with caution. Our main goal is to identify dementia, with the classification of specific types of dementia being another goal of ML models10,11. The mean ages were 77.13 (SD = 8.21) in the control group, 78.29 (SD = 6.44) in the MCI group, and 81.10 (SD = 7.56) in the dementia group. The data is posted in the Table 4.

Model classification using important features only

In the initial step, significant characteristics impacting the classification outcomes are identified with a statistical ANOVA test, for all classification scenarios (control vs. MCI, control vs. dementia (D) and control vs. combined group (MCI+D)). These features are depicted in Fig. 1. In the subsequent step, a comparative analysis is performed to assess the discriminative power of different classification algorithms.

When distinguishing between healthy controls and those with MCI, the most influential factors in the final classification are a history of myocardial infarction, vitamin D3 levels, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), age, and sodium levels (Fig. 1a). Nonlinear SVM with Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel achieves the highest accuracy, reaching 69% and an AUC value of 0.75, indicating its superior performance in discriminating between classes. The RF comes next in terms of accuracy, achieving 66% and an AUC of 0.73. Models such as linear SVM, Naive Bayes, Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and AdaBoost did not exceed 60% in ACC or 0.60 in AUC. Detailed results are presented in Table 1.

When the classification is performed between healthy controls and those with dementia, it turns out that the characteristics that have the greatest impact on the final classification are IADL, Activities of Daily Living (ADL), years of education, vitamin D3 levels and age, as depicted in the Fig. 1b). The RF demonstrates the best performance, achieving 84% accuracy and an AUC value of 0.96, which confirms its high discriminative abilities. The nonlinear SVM with RBF also yields strong results, with 77% accuracy and an AUC of 0.95. The linear SVM achieves an accuracy of up to 77% and an AUC score of 0.84, while the LDA reaches an accuracy of 76% and an AUC score of 0.83. Probabilistic classifiers, including Naive Bayes and QDA, show intermediate results for dementia, with Naive Bayes achieving an accuracy of 76% and an AUC score of 0.84, and QDA achieving an accuracy of 79% and an AUC score of 0.86. KNN achieves an accuracy of 71% and an AUC of 0.91, indicating strong class differentiation despite a moderate overall accuracy. The Gaussian Process Classifier achieves an accuracy of up to 83% and an AUC score of 0.93, while AdaBoost reaches an accuracy of 78% and an AUC score of 0.87. The summary of the results obtained is presented in Table 2.

Further differentiating features between the healthy controls group and patients with dementia are the Berg test, Body Mass Index (BMI), stroke, and potassium levels; for patients with MCI: BMI, uric acid, atherosclerosis, and education (Supplementary materials).

In the classification between healthy controls and individuals with cognitive impairment (MCI and dementia), the key characteristics influencing the accuracy of discrimination are IADL, vitamin D3 level, age, occurrence of myocardial infarction, ADL and BMI. These features are presented in the Fig. 1c). Nonlinear SVM with an RBF kernel achieves the highest accuracy, reaching 75% and an AUC value of 0.85. The RF comes next in terms of accuracy, achieving 70% and an AUC of 0.79. Some ML models achieved limited performance, with SVM, LDA, Naive Bayes, and QDA showing accuracies of 54–61% and AUCs around 0.60 to 0.62. Detailed results are presented in Table 3.

In summary, in two cases (control vs. MCI and control vs. combined group), the nonlinear SVM with the RBF kernel achieves the highest classification accuracy (ACC) and AUC-ROC metrics. In one classification scenario (control versus dementia), the RF demonstrates the best discriminative power. More detailed results for all employed classifiers are presented in the Table 1 (control vs. MCI), Table 2 (control vs. D), and Table 3 (control vs. (MCI+D)). In Fig. 2 we present, for illustrative purposes, the 2–dimensional (with only two most discriminative features for each of the classification scenario) decision boundary surfaces for the nonlinear SVM classificator with the RBF kernel.

The most important features impacting classification tasks among the following patients groups: (a) Control vs. MCI, (b) Control vs. Dementia, (c) Control vs. MCI and D combined, where control refers to subjects not exhibiting any cognitive impairment symptoms, MCI stands for Mild cognitive impairment and D denotes the patients diagnosed with dementia. The vertical line indicates the feature scoring returned by the result of F-test.

Discussion

Medical perspective

This study aims to identify cognitive impairment in patients using EMRs. The findings highlight the importance of various factors in the classification of cognitive performance among older patients, including sociodemographic variables (age, education), comorbidities (history of myocardial infarction), BMI, functional scales (IADL, ADL), as well as electrolyte disturbances and vitamin levels (sodium, vitamin D). Some of these, such as BMI42, age13,18, laboratory test parameters (hemoglobin13, mean corpuscular volume18) and comorbidities21,42, have been identified in other studies that assess the prediction of the incidence of dementia, highlighting the importance of this group of variables.

These results provide valuable insights into the key variables that differentiate these groups, improving the understanding of the data as a target for ML analysis8.For patients with MCI, who experience mild cognitive deficits that do not significantly affect their daily functioning4,41, characteristics such as age, vitamin D3 levels, and specific medical conditions (such as a history of myocardial infarction) are more crucial to distinguish them from individuals with preserved cognitive performance. Dementia, on the other hand, is characterized by more severe cognitive deficits that strongly affect the ability to perform daily activities. Therefore, IADL and ADL measures become crucial in differentiating between healthy subjects and those suffering from dementia. In the combined group of individuals with MCI and dementia, the data exhibit greater heterogeneity due to the diversity in the severity of cognitive deficits. This variability highlights the importance of considering a wide range of characteristics to capture subtle differences within this population.

Age and educational history are key features to distinguish patients with cognitive impairment from those with preserved cognitive performance. These factors have also been identified as significant features in predictive ML models for dementia18,21. Moreover, age is a non-modifiable risk factor5, while education represents a modifiable risk factor for dementia43.

In this study, functional scales are shown to be significant differentiating features between study groups, which is consistent with their importance in clinical practice5.However, it is important to consider that low IADL scores can also be the result of motor limitations rather than cognitive impairment, which requires a careful interpretation of the results. Activities of daily living (ADLs) encompass routine tasks essential for functional independence and play a crucial role in diagnosing dementia. Clinically, ADLs are classified into instrumental ADLs (IADLs), which involve cognitively demanding tasks such as managing finances and shopping, and basic ADLs (BADLs), which include procedural tasks such as bathing and eating44. A meta-analysis revealed that the participants in the AD group faced greater challenges with BADL and IADL compared to the MCI group and healthy controls. Furthermore, individuals with MCI exhibited more difficulties in these activities than healthy controls, emphasizing the importance of considering not only a decline in IADLs, but also a subtle decline in BADL abilities.45. Another meta-analysis in individuals with dementia, MCI, and healthy subjects found that IADLs were strongly related to executive function and processing speed, while ADLs (including BADLs and IADLs) were associated with global cognitive functioning and long-term verbal memory46. Some studies have used FAQ as an input variable in predictive models and classification tasks19,23,33.

BMI is another important feature in differentiating patients with cognitive impairment from those with intact cognitive performance. This study observed varying BMI levels, including obesity (BMI \(\le\) 30) and overweight (25 < BMI < 30). Obesity is recognized as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD), and epidemiological studies suggest that it may also be an independent risk factor for dementia, particularly if it occurs in middle age17,43. The Health and Retirement Study (\(n=23,000\)) found a bidirectional relationship between BMI and cognitive ability—a higher BMI is associated with a steeper decline in cognitive ability in middle and late life47. However, some evidence suggests that a higher BMI in later life may lower the risk of AD, and this process may be driven by AD-related biomarkers48. Another study found that a higher BMI was associated with a higher risk of dementia when measured more than 20 years before diagnosis, but this association reversed when the BMI was evaluated less than 10 years before diagnosis49.

Vitamin D3 levels significantly influence the differentiation between study groups. There is a notable link between vitamin D deficiency and the risk of dementia and AD, with severe deficiency (<10 ng/ml) showing a stronger association with these conditions compared to moderate deficiency (10–20 ng/ml)50. Studies on the relationship between vitamin D, cognitive function and AD suggest that vitamin D positively influences neuronal cell and microglia function, reduces inflammation, and decreases the burden of oxidative stress in the brain51. Although vitamin D plays a role in brain function and is often low in patients with dementia, inconsistencies in study methodologies, measurement techniques, and cognitive assessment criteria limit the clarity and reliability of their findings51.

In the context of ML analyses, serum sodium level has been identified as a significant feature to distinguish patients with MCI. Although average sodium levels appear similar between groups, differences in the distribution may potentially influence the variability of the results.Independent of the findings of this study, laboratory tests are generally valuable in identifying clinical factors that can contribute to cognitive decline5. Low serum sodium levels have been associated with impairments in specific cognitive domains, such as attention and psychomotor function, although no significant association was found with the overall risk of dementia52.In a retrospective cohort study, patients with severe hyponatremia were found to have a higher risk of developing dementia compared to those with non-severe hyponatremia53.

In the study group, people with dementia had higher rates of atherosclerosis, stroke, and hypertension compared to the control group. However, only a history of myocardial infarction is an influential feature in the classification of cognitive impairment. Other studies have also indicated that information on comorbidities plays a key role in accurately classifying different cognitive conditions and predicting the risk of dementia21,24. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has been suggested to accelerate cognitive decline and be a risk factor for dementia17,54. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is associated with subclinical silent myocardial infarctions and ischemic strokes, both of which are associated with an increased risk of dementia. The nervous and cardiovascular systems are interconnected through the ”heart-brain axis,” where neuronal activity, neurohormonal responses, and vasculature coordinate multisystem functions and can contribute to disease processes55. Myocardial infarction not only causes localized heart damage, but also triggers multisystemic inflammation, with evidence suggesting concurrent brain inflammation mediated by mechanisms such as microglial activation and systemic inflammatory responses56.

Perspective of machine learning models

The aim of the study is to select the most useful model to identify cognitive impairment (MCI, dementia) in older patients and to compare different models of ML. Based on the results presented in Tables. 1, 2 and 3, it can be concluded that distinguishing between controls and dementia is significantly easier than between controls and MCI33. ML models demonstrated lower performance in classifying MCI, with accuracies ranging from 50% to 69% and AUCs between 0.53 and 0.75. In contrast, the models achieved notably higher results for dementia classification, with accuracies of 58–84% and AUCs ranging from 0.51 to 0.96. ML models demonstrated varying performance in classifying the combined group (MCI + dementia), with accuracies ranging from 53% (MLP) to 75% (nonlinear SVM) and AUCs between 0.60 (MLP, QDA, LDA) and 0.85 (nonlinear SVM). The AUC and ACC values obtained in this study are consistent with the findings of other studies presented in the systematic review7,35; however, some ML models achieved lower accuracy, particularly when distinguishing between controls and MCI. Classifying patients with MCI as opposed to controls, or distinguishing AD from MCI, are more challenging tasks than classifying AD from controls, which generally results in lower accuracy (0.76–0.87)10. In the present study, lower ACC values are observed, probably due to the exclusion of neuroimaging data (e.g. MRI) and neuropsychological assessments as input variables. Such data, used in other studies, have been shown to contribute to higher ACC and AUC values19,26,36.In this study, the Grid Search method is tuned to maximize the AUC, which is why other metrics may perform weaker.It is crucial to note the variability in AUC measures and the observed accuracy rates, as similar discrepancies in classifier performance have been reported in other studies7,19,30.

Using and comparing different classification algorithms is beneficial33,40, as their effectiveness can vary depending on the specifics of the dataset57. The analysis reveals that certain ML models, particularly the nonlinear SVM and RF, demonstrate superior performance in classifying patients according to cognitive abilities. These models achieve the highest classification accuracies, as shown in Tables. 1, 2 and 3. RF effectively models nonlinear relationships and interactions between features, while nonlinear SVM is capable of capturing complex, nonlinear relationships and is suitable for datasets where patterns are not linearly separable11. These capabilities improve their ability to differentiate between groups of patients7. Specifically, the findings suggest that the nonlinear SVM model is an appropriate choice for MCI classification. In addition, it handles heterogeneous medical data and generalizes from limited training datasets, which makes it especially valuable for small to medium-sized datasets8,26. The nonlinearity of the algorithm employed is especially evident in the created decision boundaries. As depicted in Fig. 2, the boundaries obtained by the transformation of the RBF kernel are highly complex and nonlinear. Other studies also highlight the effectiveness of SVM (both linear and nonlinear) and RF in identifying MCI and AD19,26,30,33,36. Linear SVM was used more frequently15,30, probably because it was more appropriate for neuroimaging11 due to its interpretability, ability to deal with the high dimensionality of the data and lower risk of overfitting. It is important to note that although complex models such as RF and SVM with an RBF kernel demonstrate the highest accuracy, interpretation of their results can be more challenging compared to simpler models such as Naive Bayes or LDA8.

Combining the MCI and dementia groups, though partially contradictory from a medical perspective, leads to a more diverse distribution of characteristics. This approach can be applied in primary care during the initial stage, facilitating the identification of patients who require further differential diagnosis (MCI versus dementia) through neuropsychological assessment. The classification results for the combined group (MCI + dementia) further reinforce the advantages of nonlinear models, such as nonlinear SVM with an RBF kernel and RF, which achieve the highest AUC and accuracy values. Nonlinear SVM with an RBF kernel is particularly effective in modeling subtle decision boundaries, which is crucial for analyzing highly variable medical data. Furthermore, RF’s ensemble approach, based on multiple decision trees, allows it to model variable interactions and adapt to diverse data types, making it suitable for handling heterogeneous medical datasets11.

Decision boundary surfaces for the non–linear SVM classificator with the RBF kernel across three classification scenarios: (a) C vs. MCI, (b) C vs. D, (c) C vs. (MCI+D), based on two most discriminative features. D3 represents the level of vitamin D3 and ’Heart Attack’ indicates whether a patient has a history of myocardial infarction (2) or not (1) IADL and ADL refer for measures of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Activities of Daily Living, respectively.

In all models, performance disparities are evident between clinical contexts, with substantially better results for dementia classification compared to MCI. This disparity arises from the subtler and more variable clinical presentation of MCI, which complicates accurate identification, while the more distinct patterns in the dementia data facilitate classification. Linear classifiers, such as SVM with a linear kernel and LDA, and probabilistic models, including Naive Bayes and QDA, exhibit variable performance, reflecting their sensitivity to specific data features. In the case of the Naive Bayes classifier, its simplicity and the assumption of feature independence11 limit its ability to uncover complex relationships in patients with MCI. Similarly, KNN achieves higher AUC values for dementia due to closer ”neighbors” in this more homogeneous group but shows reduced accuracy and AUC for MCI due to greater variability. Other studies also confirm the effectiveness of these models in detecting cognitive impairments33.

In addition, greater clinical homogeneity among dementia patients simplifies classification. However, nonlinear models, such as RF and nonlinear SVM, excel at capturing complex patterns in multidimensional data, achieving high F1 scores (e.g., RF: F1 = 0.82; nonlinear SVM: F1 = 0.81). However, the challenge remains to identify MCI, where models such as RF and KNN demonstrate moderate performance, with F1 scores of 0.66. The results align with the findings of other studies, where the F1 scores for dementia classification were often higher19,33. In both the MCI and dementia groups, significant differences in precision and recall highlight the variability in model performance. For MCI, nonlinear SVM achieves the highest precision (0.84) but low recall (0.47), indicating that it identifies MCI cases accurately but misses many patients. For dementia, the same model shows excellent recall (0.99) but reduced precision (0.69), increasing the risk of false positives. This could lead to unnecessary pharmacological treatments and expose patients to potential side effects. KNN and RF achieve better balance, with RF showing strong precision (0.88) and recall (0.81), making it a reliable classifier for dementia. The Gaussian Process Classifier also performs well, with high precision (0.90) but moderate recall (0.77), suggesting its ability to minimize false positives while missing some cases.

No single metric fully captures the performance of the model, highlighting the importance of understanding the nuances of each metric and its clinical relevance8,9. To complement traditional metrics, the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is used as a more comprehensive measure of classification quality58. Unlike AUC, which remains the most widely used metric despite its limitations, MCC evaluates all key confusion matrix metrics-sensitivity, specificity, precision, and negative predictive value, providing a balanced view of model performance7,58.For MCI classification, MCC values are low (e.g., RF: 0.34, KNN: 0.28), reflecting limited effectiveness in distinguishing MCI patients from healthy individuals. In contrast, dementia classification achieves higher MCC values, with RF (0.71) and nonlinear SVM (0.60) performing well. The consistency of nonlinear SVM between tasks, despite moderate results, suggests robustness, while RF excels in scenarios with clearer class separations (such as dementia classification).

The comparison between AUC and MCC underscores the importance of balanced metrics in assessing ML models. Although AUC values suggest strong classification capabilities for dementia (e.g., RF: 0.96, nonlinear SVM: 0.95), MCC values (e.g., RF: 0.71, nonlinear SVM: 0.60) provide a more realistic assessment of model performance. These findings highlight the need to report both metrics to ensure a comprehensive evaluation, particularly in clinical applications where misdiagnosis can have significant consequences.

Due to clearer symptoms and more uniform patient profiles, identifying dementia in primary care can seem easier, although this approach can overlook early stages, such as MCI4. Therefore, considering models that classify both early and advanced stages of neurodegeneration is valuable, especially in terms of relevance to clinical practice.

Perspective of everyday clinical practice

EMRs data, with variables recognized as significant in the classification process, can serve as a preliminary step in detecting patients who may benefit from further neuropsychological assessment or neuroimaging5,20,24,31. Identifying dementia and conducting the necessary evaluations are essential for effective chronic disease management and planning the capacity of healthcare systems15,31,32.

Primary care physicians are encouraged to diagnose dementia and keep records to ensure adequate patient care5,25. Although the potential benefits of routinely collected EMRs data are recognized14, there are concerns about the additional documentation burden this may impose on already overburdened medical personnel59. Delegating EMR-related tasks to other team members can allow physicians to focus more effectively on diagnosing and treating patients60. Furthermore, developing research questions that can be addressed using routine EMRs data in the context of dementia should involve a multidisciplinary team, including data analysts and other healthcare professionals9,12. The application of artificial intelligence (AI) and ML to EMRs has the potential to improve disease diagnosis and symptom classification14. However, challenges such as data quality issues, missing observations, data entry errors, the potential limitations of these methods, and concerns about the ethics and safety of AI in healthcare must also be addressed7,11,14,27.

Limitations and future study

A notable limitation of this study is the small sample size of patients with dementia (n=38) and the underrepresentation of men in the study population. Initially, the goal was to identify only MCI using EMRs data; however, patients with dementia were subsequently included to determine whether the relevant classification variables would change. The small dataset in this study may affect the comparisons between models8,57. The combined group (MCI+dementia) is dominated by patients with MCI, which can affect the results. Expanding the sample size in future research would help address these issues.

Furthermore, the study’s reliance on data from a single research center may limit the generalizability of its findings. External validation is also essential to evaluate the applicability of these ML models to larger populations8,11,35. In addition, the relative homogeneity of the Polish population in terms of race and ethnicity can restrict the generalizability of the model to more diverse demographic groups8,11.

A limitation of this study is that the input data encompass a wide range of variables, including sociodemographic variables, laboratory results, comorbidities and functional scales, while the output data are limited to the results of cognitive screening tests (which are described in more detail in the Methods section). These screening tests provide only a partial view of the clinical picture; therefore, the ML models presented for classifying cognitive impairment based on EMRs should be considered only as a preliminary screening tool to be followed by further diagnostic assessments.It should also be noted that the input data lacked the parameters identified by ML models that predict dementia (such as mean corpuscular volume18) or those reported to modify the risk of dementia (e.g., high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in middle age43). Diagnoses are performed by psychologists; however, this process is susceptible to human error due to challenges such as the difficulty of detecting MCI and the risk of misclassifying it11. Despite efforts to simplify the variables as much as possible, the distinguished features identified in the analysis were functional scales (ADL and IADL), which must be completed by a qualified healthcare professional (such as a physician, nurse).

Future studies should consider a larger number of comorbidities, including estimates of their duration, and incorporate additional environmental variables, such as exposure to heavy metals, pesticides, medical factors like infectious diseases17, and polypharmacy18,61. Although including data on the duration of comorbidities was an initial assumption, obtaining this information from the EMRs was not always feasible. Using findings from studies that have elucidated risk factors for AD17,43, can help identify variables to be extracted from EMRs and collected in future studies for a more accurate classification of cognitive performance and dementia prediction. Inclusion of variables collected in the EMRs that were not previously listed as risk factors for dementia can contribute additional information18.

It is possible that alternative factors may be more critical for classifying patients according to the stage of cognitive impairment (MCI vs mild dementia)4. Furthermore, while this study aimed to identify MCI from EMRs, the traditional view of cognitive impairment as a unidirectional and progressive process is increasingly challenged by research indicating that not all patients with MCI will convert to dementia6,41,62. Future research utilizing EMRs should address the heterogeneity of MCI and the varied trajectories of cognitive decline,focusing on differentiating patients expected to remain stable from those with a higher probability of progression to dementia6,11,35. In addition, targeting the diagnosis in the preclinical stages4, which precede the onset of MCI, presents a significant challenge for ML models. It would also be valuable for future studies to investigate the influence of sex-related factors on the identified characteristics, as highlighted in previous work20. Furthermore, exploring the potential of EMRs for classifying cognitive impairment in younger patients (60 to 70 years) could provide further information.

It should be noted that EMRs are mainly used to document the clinical care of people with AD, not for research, so the use of EMRs in this area requires appropriate data completion16. In future research, data preprocessing will remain a challenge8, particularly in studies using EMRs20, and initial feature selection will be crucial to develop more precise ML models, as indicated by other studies9,19,33.

Methods

Study inclusion, exclusion and diagnostic criteria

The analysis included patients diagnosed with MCI, dementia, and healthy controls. Exclusion criteria for participation in the study were: hearing and vision impairments that hindered the evaluation of cognitive function according to the protocol, epilepsy, cancer, decompensated circulatory, respiratory, and renal failure, current oncological or palliative cancer treatment, psychiatric disorders (including depression, schizophrenia, alcohol dependence syndrome) and use of neuroleptics. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the research.

Data collection and instruments used

A multidisciplinary team of specialists was actively involved in the data collection process. A nurse completed the functional ADL63 and IADL scales64, while a physiotherapist administered the Berg Balance Scale to assess balance in older individuals65. Data on somatic comorbidities were derived from medical diagnoses recorded at hospital discharge. Cognitive assessments, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)66, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)67, and the Clock Drawing Test (CDT), were conducted by a psychologist. The scores were adjusted for age and educational level, and the Sunderland scale was used to evaluate the CDT.

Screening tools assess cognitive functions and are intended to support the identification of cognitive impairment37. Recommendations suggest that the MoCA scale is particularly effective in detecting MCI38, while the combination of MMSE and MoCA can improve diagnostic sensitivity37. In this study, both tests were used, although the MoCA was omitted in cases where it was deemed too difficult for the patient due to the advanced age or the low educational level. In these situations, only MMSE and CDT were administered to the patient.

It should be mentioned that the results of the screening test were used as labels in the output data, but not as input variables, a distinction from the common practices in other ML studies19,23,26. This approach highlights the study’s focus on leveraging sociodemographic factors, lab results, comorbidities, and functional scales for classification purposes.

Dataset

Input data included:

-

Sociodemographic variables: age, sex, education level (years),

-

Laboratory test results: levels of sodium, potassium, creatinine, hemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), vitamins D and B12, uric acid, glycated hemoglobin, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH),

-

Comorbidities: hypertension, diabetes type 2, history of myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, stroke, atherosclerosis,

-

Stressors: a variable indicating whether the patient has experienced a stressful event in the past two years,

-

BMI,

-

Functional scales: ADL, IADL, Berg scale.

The dataset includes both categorical and numerical variables. Some variables, such as the presence or absence of comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes), were encoded in binary form, while others, such as laboratory measurements (e.g., sodium and potassium levels), were recorded as numerical values. The data and its corresponding statistics are presented in Table 4.

Statistical analysis

During our statistical analysis, we exclude glycated hemoglobin due to numerous missing values. For other parameters, to handle the unavailable data points, we employ the KNN imputer algorithm. This method consists in replacing the missing parameters by the mean of N, which we find to be more appropriate than the simple substitution by the mean or median of the remaining data points. In such a manner, we derive 23 parameters that describe the state of each patient (their number after reduction is equal to n=5). Such a large number of data points makes the straightforward application of an ML algorithm impractical, as it would likely lead to overfitting. To prevent it, we reduced the number of features from 23 to 5 using the ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) test, retaining only 5 parameters with the highest F-values. This feature selection process ensures that the retained variables contribute most significantly to the classification task.

These parameters are (in descending order of significance): previous myocardial infarction (heart attack), IADL, Age, level of D3 vitamin in the blood, and Sodium in the case where classification is made between healthy patients and those diagnosed with MCI. On the other hand, when discrimination is performed between healthy patients and those suffering from dementia, the statistical test indicates that IADL, ADL, Years of Study, level of D3 vitamin in the blood, and Age are the most discriminative features. Ultimately, when comparing the control group and the group of patients diagnosed with MCI or dementia, the most significant features are: IADL, level of D3 vitamin in the blood, Age, previous myocardial infarction (heart attack), and BMI. These results are presented in Fig. 1.

In the next step, as there is a great disproportion between the number of patients assigned to the two different categories, we apply the SMOTE method (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique)11,68, to artificially elevate the number of samples in a minority class. The data preprocessed in such a manner is subsequently fed into various classification algorithms. The results are then validated on the test set with the 10-cross-validation technique. In each case, the hyperparameters of the applied model are tuned with the Grid Search method. The scheme of the applied procedure is shown in Fig. 3.

The general scheme used during ML classification involves several steps. Initially, patients are assigned to one of three categories: C (control), MCI (mild cognitive impairment), D (dementia). Then the discrimination is performed either between patients labeled as C and MCI, C and D or C and MCI+D, based on their medical records. Next, missing values in the data are handled with the KNN imputation algorithm. Subsequently, the most significant features are derived from the dataset using the univariate statistical test. To address data imbalance, the SMOTE technique is applied. Such prepared data is then fed into a ML classifier. To optimize the results, the best hyperparameters of the model are selected using Grid Search combined with k-fold Cross Validation.

The results obtained with the aforementioned strategy using scikit–learn69 Python library are introduced in the Tabs. 1 (discrimination between control and those with MCI) and 2 (discrimination between control and those with dementia).

As can be inferred from the findings presented in the Tabs. 1, 2, 3, the highest classification accuracy is obtained with nonlinear SVM (Support Vector Machine). In general, SVM are class of machine learning techniques that aim to find a hyperplane \({\textbf{w}}x+{\textbf{b}}=0\) that separates classes with a maximum margin. This means that the algorithm seeks to maximize the distance between the hyperplane and the closest data points (called support vectors) representing two categories70 (see Fig. 4). In practice, it comes down to optimizing the following loss function L:

where \(y^{(i)}({\textbf{w}}\mathbf {x_{i}}+b) \ge 1-\xi _{i}\), N denotes the number of samples and w and b are free parameters of the model to be determined during the training process. The first term in Eq. 1 is responsible for finding a maximum margin defined as the distance between the hyperplane and support vectors (presented in Fig. 4). The limitation to this term is completely sufficient for the linearly separable data and corresponds to the so–called hard–margin case. However, for the real–world data sets it is rarely the case. Therefore, it is often necessary to introduce the second term in the loss function \(C\sum _{i=1}^{N}\xi _{i}\), which violates the margin at the cost of \(C\xi _{i}\) and can be viewed as the L2 norm regularization71. \(\xi _{i}\) variable is equal to zero when the \(i^{\text {th}}\) point is correctly classified. Otherwise, its value is associated with the distance of wrongly classified samples to the margins corresponding to the correct classes. This means \(0<\xi _{i}<1\) when the margin is violated but the sample is on the right side of the hyperplane and \(\xi _{i}>1\) when it is misclassified. In summary, the loss function (Eq. 1) consists of two components. The first is associated with the minimization of the margin error (the margin maximization), while the second term is responsible for the correct data classification. To obtain the best trade–off between these two terms, it is essential to properly tune the parameter C through the GridsearchCV and cross-validation methods.

Although the above–description suggests that the support vector machines are exclusively applicable to linearly separable data, this is not the case. The most intriguing feature of this algorithm is that, after some manipulation with the loss function, we are able to successfully deal also with the samples which cannot be isolated simply with the straight line. To achieve it, we use the so–called Kernel–Trick. The process involves transforming the lower (in which the data resides) to a higher dimension space with some quadratic (kernel) functions.

Such an operation allows the identification of a nonlinear decision boundary correctly diving data points representing two categories. Various kernel functions such as polynomial, sigmoid, anova or Bessell can be employed during SVM classification. However, the most popular in real–world applications is the RBF (radial basis function) kernel defined as:

where \(||x_{1}-x_{2}||\) denotes the distance between two samples \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{2}\) and \(\sigma\) is the variance serving as the hyperparameter for the model.

Conclusions and recommendation

This study demonstrates the potential of EMRs to classify patients with cognitive impairments (MCI, dementia). The focus was on using data readily available in the medical records of the patients. The importance of various sociodemographic factors (such as age, education) and health-related variables (vitamin D levels, sodium levels, and comorbidities) in distinguishing cognitive impairment is highlighted.

In MCI classification, models show low AUC and MCC values, probably due to the heterogeneity of the group of patients. In contrast, dementia classification yields higher AUC and MCC scores, indicating that models are more effective in distinguishing dementia patients from healthy individuals. Nonlinear models, such as SVM with an RBF kernel and RF, have proven to be the most effective for analyzing EMR data, as they excel at differentiating between classes in complex datasets. Simpler models, such as KNN and Naive Bayes, perform better when dealing with more homogeneous groups, such as patients with dementia only. When both MCI and dementia groups are combined, nonlinear SVM emerges as the most accurate model.

The ML models validated in this study to classify cognitive impairments using EMRs can serve as an initial screening tool to identify cognitive decline in older patients in primary care. Neuropsychological evaluation or neuroimaging should be performed in the following stages. Although screening tests can be useful as a basis for labeling in ML models due to their availability, simplicity, and low cost, their limited accuracy and inability to reflect the full clinical picture are significant drawbacks.

Advancements in technology and computational tools enable researchers to create deep learning-driven hypotheses that can support clinical decision-making15. Moreover, quantum computing has already begun to be applied in AD diagnosis, providing a more efficient model for various disease classification tasks compared to classical ML methods72. Quantum ML has been used to evaluate neuroimaging studies, and the next challenge may be its use in the context of EMRs.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study together with the corresponding software prepared in Python is available in the Zenodo repository under the link https://zenodo.org/records/13378346.

References

Brück, C. C., Wolters, F. J., Ikram, M. A. & de Kok, I. M. Projected prevalence and incidence of dementia accounting for secular trends and birth cohort effects: a population-based microsimulation study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 37, 807–814 (2022).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the lancet commission. Lancet 396, 413–446 (2020).

Prince, M., Albanese, E., Guerchet, M. & Prina, M. World Alzheimer Report 2014. Dementia and Risk Reduction: An analysis of protective and modifiable risk factors. Ph.D. thesis, schoolAlzheimer’s Disease International (2014).

Jack, C. R. Jr. et al. Nia-aa research framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia 14, 535–562 (2018).

Gauthier, S., Rosa-Neto, P., Morais, J. A. & Webster, C. World Alzheimer report 2021: Journey through the diagnosis of dementia. Alzheimer’s Dis. Int. 2022, 30 (2021).

Tahami Monfared, A. A., Byrnes, M. J., White, L. A. & Zhang, Q. Neurol. Ther. 11, 553–569 (2022).

Chowdhury, M., Cervantes, E. G., Chan, W.-Y. & Seitz, D. P. Use of machine learning and artificial intelligence methods in geriatric mental health research involving electronic health record or administrative claims data: A systematic review. Front. Psych. 12, 738466 (2021).

Bucholc, M. et al. Artificial intelligence for dementia research methods optimization. Alzheimer’s Dementia 19, 5934–5951 (2023).

Winchester, L. M. et al. Artificial intelligence for biomarker discovery in Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimer’s Dementia 19, 5860–5871 (2023).

Li, Z., Jiang, X., Wang, Y. & Kim, Y. Applied machine learning in Alzheimer’s disease research: Omics, imaging, and clinical data. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 5, 765–777 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Understanding machine learning applications in dementia research and clinical practice: A review for biomedical scientists and clinicians. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 16, 175 (2024).

Todd, O. M. et al. New horizons in the use of routine data for ageing research. Age Ageing 49, 716–722 (2020).

Park, J. H. et al. Machine learning prediction of incidence of Alzheimer’s disease using large-scale administrative health data. NPJ Digit. Med. 3, 46 (2020).

Bednorz, A., Mak, J. K., Jylhävä, J. & Religa, D. Use of electronic medical records (EMR) in gerontology: Benefits, considerations and a promising future. Clin. Interv. Aging 18, 2171–2183 (2023).

Kumar, S. et al. Machine learning for modeling the progression of Alzheimer disease dementia using clinical data: A systematic literature review. JAMIA Open 4, 052 (2021).

Zhang, R., Simon, G. & Yu, F. Advancing Alzheimer’s research: A review of big data promises. Int. J. Med. Inform. 106, 48–56 (2017).

Breijyeh, Z. & Karaman, R. Comprehensive review on Alzheimer’s disease: Causes and treatment. Molecules 25, 5789 (2020).

You, J. et al. Development of a novel dementia risk prediction model in the general population: A large, longitudinal, population-based machine-learning study. EClinicalMedicine 53, 101665 (2022).

El-Sappagh, S., Alonso, J. M., Islam, S. R., Sultan, A. M. & Kwak, K. S. A multilayer multimodal detection and prediction model based on explainable artificial intelligence for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 2660 (2021).

Tang, A. S. et al. Leveraging electronic health records and knowledge networks for Alzheimer’s disease prediction and sex-specific biological insights. Nat. Aging 4, 379–395 (2024).

Zhou, J. et al. Identifying dementia from cognitive footprints in hospital records among Chinese older adults: A machine-learning study. Lancet Reg. Health-Western Pac. 46, 101060 (2024).

Nori, V. S., Hane, C. A., Sun, Y., Crown, W. H. & Bleicher, P. A. Deep neural network models for identifying incident dementia using claims and EHR datasets. PLoS ONE 15, e0236400 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. A high-generalizability machine learning framework for predicting the progression of Alzheimer’s disease using limited data. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 43 (2022).

Abuhantash, F., Abu Hantash, M. K. & AlShehhi, A. Comorbidity-based framework for Alzheimer’s disease classification using graph neural networks. Sci. Rep. 14, 21061 (2024).

Ford, E. et al. Automated detection of patients with dementia whose symptoms have been identified in primary care but have no formal diagnosis: a retrospective case-control study using electronic primary care records. BMJ Open 11, e039248 (2021).

Vichianin, Y. et al. Accuracy of support-vector machines for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, using volume of brain obtained by structural mri at siriraj hospital. Front. Neurol. 12, 640696 (2021).

Fisher, C. K., Smith, A. M. & Walsh, J. R. Machine learning for comprehensive forecasting of Alzheimer’s disease progression. Sci. Rep. 9, 13622 (2019).

Abrol, A. et al. Deep residual learning for neuroimaging: An application to predict progression to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. Methods 339, 108701 (2020).

Basaia, S. et al. Automated classification of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment using a single MRI and deep neural networks. NeuroImage Clin. 21, 101645 (2019).

Arbabshirani, M. R., Plis, S., Sui, J. & Calhoun, V. D. Single subject prediction of brain disorders in neuroimaging: Promises and pitfalls. Neuroimage 145, 137–165 (2017).

Shao, Y. et al. Detection of probable dementia cases in undiagnosed patients using structured and unstructured electronic health records. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19, 1–11 (2019).

Miled, Z. B. et al. Predicting dementia with routine care EMR data. Artif. Intell. Med. 102, 101771 (2020).

Alatrany, A. S., Khan, W., Hussain, A., Kolivand, H. & Al-Jumeily, D. An explainable machine learning approach for Azheimer’s disease classification. Sci. Rep. 14, 2637 (2024).

Mohammed, B. A. et al. Multi-method analysis of medical records and MRI images for early diagnosis of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease based on deep learning and hybrid methods. Electronics 10, 2860 (2021).

Martin, S. A., Townend, F. J., Barkhof, F. & Cole, J. H. Interpretable machine learning for dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dementia 19, 2135–2149 (2023).

Akramifard, H. et al. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on clinical trials, three-dimensional imaging data, and personal information using autoencoders. J. Med. Signals Sens. 11, 120–130 (2021).

Larner, A. Manual of Screeners for Dementia: Pragmatic Test Accuracy Studies (Springer Nature, 2020).

De Roeck, E. E., De Deyn, P. P., Dierckx, E. & Engelborghs, S. Brief cognitive screening instruments for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Alzheimer’s Rese. Ther. 11, 1–14 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Generalizable deep learning model for early Alzheimer’s disease detection from structural MRIS. Sci. Rep. 12, 17106 (2022).

Jordan, M. I. & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 349, 255–260 (2015).

Petersen, R. C. Mild cognitive impairment. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 22, 404–418 (2016).

Walters, K. et al. Predicting dementia risk in primary care: Development and validation of the dementia risk score using routinely collected data. BMC Med. 14, 1–12 (2016).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet 404, 572–628 (2024).

Yemm, H. et al. Instrumental activities of daily living scales to detect cognitive impairment and dementia in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 83, 451–474 (2021).

Altieri, M., Garramone, F. & Santangelo, G. Functional autonomy in dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy aging: A meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 42, 1773–1783 (2021).

Raimo, S. et al. The relation between cognitive functioning and activities of daily living in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: A meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 45, 2427–2443 (2024).

Karlsson, I. K., Gatz, M., Arpawong, T. E., Dahl Aslan, A. K. & Reynolds, C. A. The dynamic association between body mass index and cognition from midlife through late-life, and the effect of sex and genetic influences. Sci. Rep. 11, 7206 (2021).

Sun, Z. et al. Late-life obesity is a protective factor for prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: A longitudinal study. Aging (Albany NY) 12, 2005 (2020).

Kivimäki, M. et al. Body mass index and risk of dementia: Analysis of individual-level data from 1.3 million individuals. Alzheimer’s Dementia 14, 601–609 (2018).

Chai, B. et al. Vitamin d deficiency as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: An updated meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 19, 1–11 (2019).

Bivona, G. et al. The role of vitamin d as a biomarker in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Sci. 11, 334 (2021).

Van Der Burgh, A. C. et al. Serum sodium, cognition and incident dementia in the general population. Age Ageing 52, afad007 (2023).

Chung, M.-C. et al. Hyponatremia and increased risk of dementia: A population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 12, e0178977 (2017).

Schievink, S. H. et al. Cognitive changes in prevalent and incident cardiovascular disease: A 12-year follow-up in the Maastricht aging study (MAAS). Eur. Heart J. 43, e2–e9 (2022).

Thong, E. H. E. et al. Acute myocardial infarction and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: A review. Biology 12, 1154 (2023).

Chandrashekhar, Y. & Narula, J. Imaging dynamic heart-brain interactions: Getting to the heart of the matter, gray and white. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71(3), 276–278 (2018).

Fernández-Delgado, M., Cernadas, E., Barro, S. & Amorim, D. Do we need hundreds of classifiers to solve real world classification problems?. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 3133–3181 (2014).

Chicco, D. & Jurman, G. The Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) should replace the ROC AUC as the standard metric for assessing binary classification. BioData Min. 16, 4 (2023).

Johnson, K. B., Neuss, M. J. & Detmer, D. E. Electronic health records and clinician burnout: A story of three eras. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28, 967–973 (2021).

Singh, N., Lawrence, K., Sinsky, C. & Mann, D. M. Digital minimalism-an RX for clinician burnout. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1158–1159 (2023).

Rawle, M. J., Cooper, R., Kuh, D. & Richards, M. Associations between polypharmacy and cognitive and physical capability: A British birth cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 916–923 (2018).

Ganguli, M. et al. Mild cognitive impairment that does not progress to dementia: A population-based study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 232–238 (2019).

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A. & Jaffe, M. W. Studies of illness in the aged: The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185, 914–919 (1963).

Lawton, M. Assessment of older people; self-maintaining and instrumental activites of dialy living. Gerontologist 9, 279–286 (1969).

Berg, K., Wood-Dauphine, S., Williams, J. & Gayton, D. Measuring balance in the elderly: Preliminary development of an instrument. Physiother. Can. 41, 304–311 (1989).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Chawla, N. V., Bowyer, K. W., Hall, L. O. & Kegelmeyer, W. P. Smote: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 16, 321–357 (2002).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Boser, B. E., Guyon, I. M. & Vapnik, V. N. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. in Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on Computational learning theory, 144–152 (1992).

Bishop, C. M. & Nasrabadi, N. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning Vol. 4 (Springer, 2006).

Jenber Belay, A., Walle, Y. M. & Haile, M. B. Deep ensemble learning and quantum machine learning approach for Alzheimer’s disease detection. Sci. Rep. 14, 14196 (2024).

Funding

The study was funded by the Development Fund of the Cracow Institute of Technology and the subsidy from Akademia Humanitas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.-L. analysed the results, wrote the software, wrote the draft of the manuscript, visualized the results, E.S. wrote the draft of the manuscript, A.B. collected the data, wrote the draft of the manuscript, supervised the project and analysed the obtained results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Committee of Bioethics for Scientific Research of the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice (Resolutions No. 2/1/2015 and No. 1/2015). All participants provided their informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Richter-Laskowska, M., Sobotnicka, E. & Bednorz, A. Cognitive performance classification of older patients using machine learning and electronic medical records. Sci Rep 15, 6564 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90460-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90460-y