Abstract

There were no pediatric oncology centers in Northwest Ethiopia before 2019. This retrospective cross-sectional study aims to describe the magnitude and associated factors of childhood cancer treatment abandonment at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the first pediatric oncology unit in Northwest Ethiopia. Survival rates of childhood cancer in low and middle-income countries are as low as 30%. Treatment abandonment is the main reason for low childhood cancer survival rates. Multivariate complementary log-log regression analysis was used to determine factors associated with childhood cancer treatment abandonment. The statistical association between dependent and. independent variables were declared at a p-value of ≤ 0.05. The magnitude of treatment abandonment was 39.2%. The disbelief cancer is incurable (AOR = 2.33), child looked cure (AOR = 4.22), the occurrence of treatment-related toxicities (AOR) = 1.77 ), any of cancer relapse or cancer progression or stable diseases (AOR) = 2.74), being in active treatment phase (AOR) = 15.37), having health insurance (AOR = 0.46), and primary caregivers have a job (AOR = 0.34 ) were significantly associated with childhood treatment abandonment. The study result showed that the magnitude of childhood cancer treatment abandonment was a significant problem at the UOGCSH. Having health insurance and employed primary caregivers were associated with reduced treatment abandonment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Each year, it is estimated that 400,000 children develop cancer globally (age range, 0–19 years ). 90% of childhood cancer occur in low- and middle-income countries, where survival rates can be as low as 30%1.

Some of the factors contributing to the disparity in childhood cancer care and survival rates include lack of access to appropriate cancer care facilities, untimely and inaccurate diagnoses, and high rates of treatment abandonment2,3.

Cancer is becoming a major public health problem globally and a leading cause of disease-related mortality and morbidity in children worldwide. Childhood cancer incidence has increased by 13% globally. However, little is known about the epidemiology of childhood cancer in Ethiopia. The overall incidence rate of childhood cancer in Ethiopia from one population-based study is 81.9 cases per million4.

With early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, more than 70% of children with cancer in the developed world are cured. In low and middle-income countries, treatment abandonment is the main reason for both childhood cancer treatment failure and low survival rates5.

Due to a lack of resources and organizational facilities, childhood cancer is at high risk of under-treatment6.

Though factors contributing to treatment abandonment vary across the globe, treatment toxicity and financial constraints are among the many7.

Treatment abandonment rates average 3% in HICs and 30% in LMICs.

and are predicted by lower Gross National Product per capita, absence of national health insurance schemes, and high prevalence of economic hardship. Other predictors include low socio-economic status, poor literacy, increased hospital travel time, and lack of affordable local treatment8.

The perceived mean abandonment rate in Ethiopia is 34%. The risk of treatment abandonment is dependent on the type of cancer (high for bone sarcoma and brain tumor), the phase of treatment, and treatment outcome. The major influencing risk factors in Ethiopia include high cost of care, low economic status, long travel time to treatment centers, long waiting time, belief in the incurability of cancer, and poor public awareness about childhood cancer9.

Improving the healthcare system, and increasing awareness of childhood cancer will increase the number of reported cases of pediatric cancer10.

The cure rate of childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa is often less than 25%11.

Because of their need for more specialized treatment, childhood cancer treatment abandonment determinants are various. Out of the many causes, guardians’ knowledge and beliefs about cancer treatment and outcome are the main factors12.

Method

An institution-based retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted on 403 children with cancer at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, the only Pediatric Hematology Oncology Treatment center in the Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia, serving around 23.3 Million People.

Source population

All patients admitted to the UOGCSH pediatrics wards, pediatric hematology-oncology ward, PICU, and NICU and who came for follow-up between July 30, 2019, and August 1, 2023.

Study population

All children aged less than 19 years admitted to the UOGCSH pediatric hematology-oncology ward and or who came for follow-up with cancer in the study period.

Inclusion criteria

All children aged less than 19 years with a diagnosis of cancer admitted to pediatric hematology-oncology ward and/or follow-up.

Exclusion criteria

Children with no access to their primary caregivers’ contact information, primary caregivers refused telephone conversations, and missed medical files were excluded from the study. Medical record review and phone conversations of primary caregivers/legal guardians were used for data collection. The questionnaires we used to collect data were developed for this study not published elsewhere. Data were collected by 3 trained general practitioners using a structured questionnaire.

Upon phone conversation, informed consent was taken from.

Primary caregivers /legal guardians or assent was taken from the patients who were older than 15 years.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the School of Medicine Ethical Review Committee of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Sciences with reference number 634/2023.

In this study, socio-demographic variables of primary caregivers and children were included in the questionnaire. The types of cancer, treatment phase, duration of treatment, and possible reasons for treatment abandonment were also assessed.

Operational definition

Children

The child is a human being who is below the age of 19 years13.

Canceris a broad term given to a collection of related diseases involving the abnormal growth and division of cells in an uncontrolled way with the potential to invade nearing tissue or spread to other parts of the body14.

Treatment abandonment is the failure to either begin or complete cancer therapy that would cure or contain the disease and/or missing treatment appointments for ≥ 4 consecutive weeks that impact the ability to cure or contain the disease15.

Urban

Regional capitals, Zonal capitals, and Wereda capitals16.

Rural- comprises all areas not classified as urban16.

Data processing and analysis.

Data were entered into Epi info version 7 and then exported to STATA version 14 for statistical analysis after it was double-checked for consistency and completeness.

Descriptive statistics like median and interquartile range were computed to summarize baseline socio-demographic variables.

Variables with a p-value of less than 0.2 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis.

A complementary log-log regression model was used to identify factors associated with treatment abandonment.

Adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated and variables with a p-value less than 0.05 in the multi-variable analysis were considered to declare factors associated with treatment abandonment.

Result

Background characteristics of patients and primary caregivers

We studied 403 children with cancer who visited the UOGCSH Pediatric Hematology Oncology Unit with a response rate of 96.3%. Treatment status was documented in 388 patients. One hundred fifty-two (39.2% ) abandoned treatment.

The median age of the patients was 6 years and the interquartile range of 3 and 10 years. Of the participants included in the analyses, 256 (66%) were males. Most of these patients 323 (83.2%) were residing in rural.

The median age of the caregivers was 39 years and the interquartile range of 35 and 44 years.

Three hundred sixty-one (93%) of the attendants had their job. The majority (55.4%) of the primary caregivers didn’t attend formal education.

Most of the patients 230 (59.3%) didn’t have health insurance the remaining 40.7% were insured. Among patients who abandoned treatment 122 (80.3%) didn’t have health insurance. Table 1.

Disease distribution and treatment status

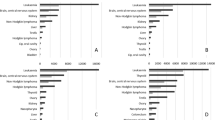

In this study, the 6 most common childhood cancers were Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (21.9%), Wilms Tumor (11.9%), Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (11.3%), Retinoblastoma (10.8%), Hodgkin Lymphoma (9.3%) and Bone Sarcomas (9%). Figure 1.

Males account for 96 (63.2% ) of treatment abandonment. Childhood cancers with the most frequent treatment abandonment rates were Acute lymphoblastic leukemia 28 (18.4%), Retinoblastoma 19 (12.5%), Wilms tumor and bone sarcoma each 16 (10.5%), Rhabdomyosarcoma 15 (9.9%) followed by Non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma each 13 (8.6%).

The most common treatment phase when patients abandoned their treatment was in active treatment 279 (71.9%) followed by follow-up after treatment completed 67 (17.3%) and before chemotherapy was initiated 42 (10.8%). Sixty-seven (17.3%) patients completed treatment and they all are alive on follow up while 169 ( 43.6%) are on active treatment.

Reasons for treatment abandonment

One hundred fifty-two (39.2%) reported reasons for treatment abandonment with a 95% confidence interval (34.3–43.3%).

The most common reasons were the disbelief that cancer is incurable 108 (71.1%), financial constraints ( transport, hospital bed, laboratory, and medicine costs) 46 (30.3%), fear of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures 36 (23.7%), seek of alternative treatment 34 (22.4%), clinical deterioration (imminent death ) 22 (14.5%) and long treatment course 14 (9.2%).Table 2.

Factors Associated with Treatment Abandonment

From the multivariate complementary log-log regression analysis,

In perception and awareness-related factors on childhood cancer: the disbelief that cancer is incurable, the child looked a cure (caregivers’ premature declaration of cure before the intended treatment is completed ), the occurrence of treatment-related complications, disease relapse or progressive disease or stable disease, seek for alternative treatment, being on active treatment phase and duration of treatment less than 6 months were significantly associated with childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

In social factors, health insurance status and employment status of primary caregivers were significantly associated with childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

Children whose parents believed cancer was incurable were 2.33 times at high risk for treatment abandonment (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 2.33 (95% confidence interval [CI]: (1.44,3.74); p = 0.001 ), children whose parents declared premature cure before the intended treatment completed were 4.22 times high risk for treatment abandonment (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 4.22 (95% confidence interval [CI]: ( 1.51, 11.77); p = 0.006 ) and children with any of treatment-related complications were 1.77 times high risk for treatment abandonment [AOR] = 1.77 (95% confidence interval [CI]: ( 1.08,2.91) ; p = 0.024 ).

Children with either of the events like disease relapse or disease progress or stable diseases were 2.74 times high risk for treatment abandonment (AOR) = 2.74 (95% CI: (1.26,5.96);P = 0.011),children who seek alternative treatment were 1.17 times high risk for treatment abandonment (Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.17 (95% confidence interval [CI]: (0.65, 2.10); p = 0.595 ),children who were on active treatment phase were 15.37 times high risk for treatment abandonment compared to those completed treatment [AOR] = 15.37(95% confidence interval [CI]: (2.02, 116.88); p = 0.008),children with cancer during the first 6 months of treatment were 1.13 times high risk for treatment abandonment (Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.13 (95% confidence interval [CI]: (0.65 1.95); p = 0.668 ) and children with clinical deterioration (imminent death ) were 1.54 times high risk for treatment abandonment (AOR = 1.54 (95% CI:0.85,2.78);p = 0.15).

The odds of treatment abandonment for those who had health insurance was : (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 0.46 (95% confidence interval [CI]: (0 0.27,0 0.76); p = 0.003 ), and those whose primary caregivers had a job was (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 0.34 (95% confidence interval [CI]: (0 0.18,0 0.65); p = 0.001 ).Table 3.

Note : *** = P value < 0.01, **= P value between 0.01 and 0.05 and * = P value > = 0.05.

Discussion

Although treatment abandonment is complex and multi-factorial, understanding and addressing it is found to be mandatory to narrow the survival gap between HIC and LMIC. The results of our study identified statistically significant factors associated with childhood cancer treatment abandonment such as the employment status of the caregivers, health insurance status, treatment phase, duration of treatment, and caregivers’/legal guardians’ beliefs on cancer treatment outcome.

In our study, there was no statistically significant association between the age of both patients and primary caregivers/legal guardians, sex of both patients and primary caregivers/legal guardians, residence of both patients and primary caregivers/legal guardians, primary caregivers/legal guardians educational status, relation of caregivers/legal guardians to the patient, and type of cancer and the childhood cancer treatment abandonment. In this study, the majority of our patients were from rural residences, but it was not found to have a statistically significant association with childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

The treatment abandonment rate in this study was 39.2% which is similar to the other studies done in Kenya (34%)17 and in Ethiopia, the perceived mean abandonment rate in Ethiopia is (34%)(SE 2.5%)9.

It is lower than other studies done in Kenya cross-sectional study 54%18, Indonesia 48%19. The Kenyan treatment abandonment is higher it could be due to the negative beliefs of families on cancer treatment and its outcome and patient retention policy in Kenya18.

On the contrary, it is higher than in the studies done in North East India at 27.1%20, in Pediatric Patients at a Low-Resource Cancer Center in India treatment abandonment rate was 20%10, an online survey study of the treatment abandonment rate was 15%21and in Colombian study it was 21%22. This could be due to a difference in socioeconomic status, treatment setup, and caregivers’ perception of cancer treatment and outcome.

Out of the factors we assessed in this study, the employment status of caregivers, phases of treatment, treatment-related complications, health insurance status, seeking for alternative treatment, duration of treatment, and the disbelief that cancer is incurable were statistically significant.

Children who were insured (have health insurance ) had a 54% reduced treatment abandonment rate compared to those who were not insured. In our study 80.3% of children with cancer who were not insured abandoned treatment. This finding is supported by a retrospective study done in Kenya17. This could be due to financial constraints as health insurance in our country covers hospital beds, medicines, and laboratory costs so being insured reduces financial constraints.

Children who sought alternative treatment had 1.17 times higher odds of treatment abandonment compared to those who didn’t seek alternative treatment which is consistent with a study done in Indonesia19. This could be due to the primary caregivers/legal guardians thought the health of the child was beyond medicine. Traditional healers and religious options could be among the reasons that children with cancer seek alternative treatment.

Treatment abandonment among children with cancer who had either disease relapse, progression, or stable disease was 2.74 higher compared to those who had neither of these events. This finding was supported by an online survey23and another study in East India20. This could be due to the primary caregivers/legal guardians’ loss of hope of cure as there are limited treatment options for refractory, relapse, and stable childhood cancer in our treatment center.

Treatment abandonment among children whose primary caregivers declared premature cure before the intended treatment was completed (the child looked cured) was 4.22 times higher than among those whose primary caregivers didn’t think so. The reasons for the premature declaration of cure could be due to the treatment-induced resolution of symptoms which the primary caregivers perceived as a cure before the treatment is completed.

Abandonment among children whose primary caregivers believed that cancer was incurable was 2.33 times higher than those who believed cancer was curable. In our study, it was reported by 71.1% of caregivers of treatment abandoned children as a main reason. This finding was supported by a study done on treatment refusal and abandonment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Indonesia24. This could be due to primary caregivers’ /legal guardians’ low perception of cancer curability. Their disbelief that cancer is incurable could be due to previous bad experiences they heard or had. The odds of treatment abandonment among patients who experienced treatment-related complications (side effects ) were 1.77 times higher than those who didn’t experience side effects. This finding was supported by a study done on treatment refusal and abandonment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Indonesia24. This could be due to the primary caregivers/legal guardians worried more about side effects than the primary disease.

Childhood cancer during the first 6 months of treatment had 1.13 times higher odds of treatment abandonment as compared to after 6 months of treatment which is supported by a study done in West Kenya which 52% of treatment abandonment was during the first 6 months of therapy period25and supported by another study26. The possible reasons for the high rate of treatment abandonment during the first 6 months of therapy can be due to the higher frequency of treatment-related toxicities as more intensive treatment is given in the early phases of almost all cancer types, more frequent diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are done early in the treatment phases and frequent hospital admissions due to treatment-related toxicities or for intensive treatment per protocol early in the treatment course than late in the treatment course. Children whose primary caregivers have a job (regular income) had a 66% treatment abandonment reduction compared to children whose primary caregivers didn’t have a job. This is supported by a study done in West Kenya which 70% of children with childhood cancer treatment abandoned their parents who had no regular income25. This could be explained by reduced financial challenges. Children who were on active treatment had 15.37 times higher odds of treatment abandonment compared to those who didn’t start treatment and who completed treatment. This finding is supported by a study ‘The magnitude and perceived reasons for childhood cancer treatment abandonment in Ethiopia: from health care providers’ perspective9. This could be explained by, children in active cancer treatment periods, having frequent occurrences of treatment-related toxicities, financial problems, frequent hospital visits, and prolonged hospital stays.

Conclusion

The study result showed that the magnitude of childhood cancer treatment abandonment was a significant problem at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. Having health insurance and employed primary caregivers were associated with reduced treatment abandonment while the disbelief that cancer is incurable, seeking alternative therapy, the child looked cure, being in the active treatment phase, the first 6 months of the treatment phase, the occurrence of treatment-related complications, disease relapse/progression/stable disease and clinical deterioration was found positively associated with increased childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

Limitations of the study

Since it was a retrospective study, it was quite difficult to trace some of the caregivers due to missing or outdated contact. Some of the medical records were incomplete.

Recommendations: Based on the findings of this study, we recommend that governments ensure that more families get enrolled in health insurance as this was shown in our study to have a reduction in childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

We believe social/economic/psychological support to the primary caregivers/legal guardians who don’t have a regular income (job) will reduce childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

Improving public awareness of childhood cancer treatment and its outcome is essential to convince families to adhere to therapy.

Further prospective studies are recommended to identify more predictors of childhood cancer treatment abandonment.

Data availability

Data Material is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARs:

-

Abandonment rates

- GC:

-

Gondar College

- UOGCSH:

-

University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- HIC:

-

High Income Countries

- LMIC:

-

Low and Middle-Income Countries

- NICU:

-

Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

- PICU:

-

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- TxA:

-

Treatment abandonment

References

Cayrol, J., Ilbawi, A., Sullivan, M. & Gray, A. The development and education of a workforce in childhood cancer services in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review protocol. Syst. Rev. 11 (1), 167 (2022).

Hordofa, D. F. et al. Childhood cancer presentation and initial outcomes in Ethiopia: findings from a recently opened pediatric oncology unit. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 4 (7), e0003379 (2024).

Nanteza, S. et al. Treatment abandonment in children with Wilms tumor at a national referral hospital in Uganda. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 40 (1), 162 (2024).

Belay, A. et al. Incidence and pattern of childhood cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2012–2017). BMC Cancer. 23 (1), 1261 (2023).

RS ARORA* BPATE. Understanding Refusal and Abandonment in the Treatment of Childhood Cancer. (2010).

Valsecchi, M. G. et al. Clinical epidemiology of childhood cancer in Central America and Caribbean countries. Ann. Oncol. 15 (4), 680–685 (2004).

Gupta, S. et al. The magnitude and predictors of abandonment of therapy in pediatric acute leukemia in middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer. 49 (11), 2555–2564 (2013).

Atwiine, B. et al. Money was the problem: caregivers’ self-reported reasons for abandoning their children’s cancer treatment in southwest Uganda. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 68 (11), e29311 (2021).

Mirutse, M. K. et al. The magnitude and perceived reasons for childhood cancer treatment abandonment in Ethiopia: from health care providers’ perspective. BMC Health Serv. Res. 22 (1), 1014 (2022).

Sinha, S. et al. Treatment adherence and abandonment in Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Pediatric patients at a low-resource Cancer Center in India. Indian J. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 40 (04), 501–506 (2021).

Slone, J. S. et al. Pediatric malignancies, treatment outcomes and abandonment of pediatric cancer treatment in Zambia. PLoS One. 9 (2), e89102 (2014).

Stanley, C. C. et al. Risk factors and reasons for treatment abandonment among children with lymphoma in Malawi. Support Care Cancer. 26 (3), 967–973 (2018).

<978-3-030-84647-3.pdf>.

.

Meaghann, S. et al. MPH. <weaver2015.pdf></weaver2015.pdf> (MD, 2015).

Meaghann, S. et al. Urban and Rural definition.pdf>.

& GOHAMFNSLSMJS, T. Vik3 & G. J. L. Kaspers 2 SM. Influence of health insurance status on childhood cancer treatment.

outcomes in Kenya. Supportive Care in Cancer.

https:/. /doiorg/101007/s00520-019-04859-1. (2019).

Mostert, S. et al. Two overlooked contributors to the abandonment of childhood cancer treatment in Kenya: parents’ social network and experiences with hospital retention policies. Psychooncology 23 (6), 700–707 (2014).

Mostert1, S. & *, S. G. Kaspers1 S. Socio-economic status plays important roles in childhood cancer treatment outcomes in Indonesia. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 13 (12), 6491–6496 (2012).

Hazarika, M. 1 et al. Causes of Treatment Abandonment of Pediatric Cancer.

Patients – Experience in a Regional Cancer Centre in North.

East & India.

Asian Pac J. Cancer Prev., 20 (4), 1133–1137. (2019).

Friedrich, P. et al. The magnitude of treatment abandonment in Childhood Cancer. PLoS One. 10 (9), e0135230 (2015).

Ospina-Romero, M., Portilla, C. A., Bravo, L. E., Ramirez, O. & group Vw. Caregivers’ self-reported absence of Social Support Networks is related to treatment abandonment in Children with Cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 63 (5), 825–831 (2016).

Friedrich, P. et al. Determinants of treatment abandonment in Childhood Cancer: results from a global survey. PLoS One. 11 (10), e0163090 (2016).

Sitaresmi, M. N., Mostert, S., Schook, R. M. & Sutaryo, Veerman, A. J. Treatment refusal and abandonment in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Indonesia: an analysis of causes and consequences. Psychooncology 19 (4), 361–367 (2010).

Choonara, I. Abandonment of childhood cancer treatment in Western Kenya. crossMark 99 (7), 605–606 (2014).

RS ARORA* BPATE. Understanding Refusal and Abandonment in the treatment of Childhood Cancer. Indian Pediatr. ;47. (2010).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the study participants, data collectors, supervisors, The Aslan Project, and hospital administrators of the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

Funding

The data collection of this study was funded by the University of Gondar,the institution (University of Gondar) doesn’t have a role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the decision to publish or preparation of manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yalew Melkamu Molla designed the study, performed data analysis, visualized, and validated the whole work, and prepared the manuscript. Mulugeta Ayalew Yimer, Aziza T. Shad, and Rabia Wali all participated in designing the study, visualization, and validation of the whole work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the methods and procedures in this study were carried out by the Helsinki and ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar (ref.no 634/2023). As the study was retrospective (medical record review and phone conversation for additional information that was not available on the medical record), informed consent was taken upon phone conversation from the primary caregivers/legal guardians, and assent was taken from the patients who are older than 15 years. All information retrieved was used only for study purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Molla, Y.M., Shad, A., Wali, R. et al. The magnitude and associated factors of childhood cancer treatment abandonment at the university of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 10534 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90493-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90493-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Strengthening the Pediatric Germ Cell Tumor Care Landscape in LMICs

Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2025)

-

From Interaction to Intervention: Intentional CYP Inhibition as a Scalable Strategy to Expand Access to High-Cost Therapies

European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics (2025)