Abstract

Pinus yunnanensis is an important coniferous species for both ecological and economic purposes in Southwest China. However, its seedlings grow slowly and show low productivity, with notable trait variability under the same cultivation conditions. These characteristics limit its extensive use in reforestation and forest management. Photosynthesis is the foundational process for plant growth and biomass accumulation. Chlorophyll, as the essential pigment in photosynthesis, directly impacts the synthesis of organic materials and the increase in biomass. In this study, the seedlings of P. yunnanensis were classified into three grades (I, II, and III) using the mean value ± 1/2 standard deviation method (H ± 1/2σ). Various growth traits, such as the number of branches, plant height, stem thickness, needle length, root characteristics, and biomass, were measured at multiple time points. The content of photosynthetic pigments was determined using spectrophotometry, endogenous hormone levels were analyzed by LC-MS/MS, and the expression of genes related to chlorophyll metabolism was detected through qRT-PCR. Pearson correlation analysis was employed to quantify the associations between hormone content, gene expression, and the seedlings’ morphological characteristics. The results indicate that Grade I significantly outperform Grades II and III in terms of above-ground growth metrics. During the rapid growth period in March, Grade I seedlings had the highest chlorophyll content, potentially enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and increasing biomass allocation. Hormonal analysis revealed that compared to other grades, Grade I seedlings exhibited higher levels of ABA, JAs, and ACC, while Auxins and SAs were lower; there was no significant difference in CTK content between Grade I and Grade II, both of which were lower than in Grade III. qRT-PCR analysis confirmed that the expression of genes related to chlorophyll synthesis was significantly upregulated in Grade I seedlings. In contrast, the expression of genes associated with chlorophyll degradation was more active in Grade III seedlings. Correlation analysis further emphasized the strong link between hormone levels, gene expression, and growth traits. This study delves into the intrinsic mechanisms of morphological differentiation in P. yunnanensis seedlings by examining the synergistic effects of chlorophyll metabolism and endogenous hormone regulation. These findings can provide valuable references for cultivating high-quality seedlings, optimizing seed source selection, and improving afforestation techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chlorophyll is the core pigment essential for the normal process of photosynthesis. It is primarily found in green plants, algae, and photosynthetic bacteria. It is located within the thylakoid membranes of chloroplasts, where it absorbs, transfers, and converts light energy to facilitate carbon assimilation1,2. The content of chlorophyll (total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b) and accessory pigments such as carotenoids in leaves not only reflects the photosynthetic capacity and resource acquisition efficiency of plants but is also commonly used as a crucial indicator of plant growth condition3. Currently, the biosynthetic pathway of chlorophyll from L-glutamyl-tRNA to chlorophyll a and then to chlorophyll b is relatively well understood. It involves up to 15 enzyme-catalyzed reactions and 27 enzyme-encoding genes. The HEMA1 gene encodes glutamyl-tRNA reductase, a key rate-limiting enzyme in the early stages of chlorophyll synthesis, while the GSA gene regulates the production of 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), directly determining the subsequent synthesis rate4,5. The CAO gene controls the critical reaction converting chlorophyll a to chlorophyll b, thereby regulating the ratio of chlorophyll a to b6. During the degradation phase, the functionality of genes such as CLH (chlorophyllase)7, PPH (pheophytinase)8, PAO (pheophorbide a oxygenase)9, and RCCR (red chlorophyll catabolite reductase)10 is crucial for chlorophyll breakdown. Deficiencies in these genes can lead to the accumulation of toxic intermediates, adversely affecting cell health and plant growth8,9,11. Conversely, the SGR (Stay-green) gene is considered a crucial ‘switch’ for regulating chlorophyll degradation. Overexpression of SGR accelerates leaf senescence and reduces photosynthetic efficiency12,13.

In addition to genetic factors, plant hormones play a crucial role in regulating chlorophyll synthesis and degradation, photosynthetic efficiency, and seedling growth and development14,15,16,17. Existing research indicates that auxins (IAA) and cytokinins (CTK) influence chloroplast development, leaf structure, and photosynthetic efficiency. Variations in their levels or ratios often result in differences in photosynthetic characteristics and growth potential18,19,20. For example, the accumulation of carotenoids during the ripening of tomato fruits is regulated by the balance between auxins and ethylene21. Abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid (JA), and salicylic acid (SA) are more extensively involved in plant perception and response to stress signals, indirectly affecting chlorophyll degradation and the aging process22,23,24.

P. yunnanensis, a light-loving, deep-rooted coniferous tree species, is widely distributed in the southwestern region of China. Due to its high adaptability to poor soils, it has become one of the main species for afforestation and timber production in arid mountainous areas25,26. However, its seedlings exhibit slow growth and low productivity and demonstrate significant phenotypic differentiation under the same environmental conditions. These factors limit its survival rate in afforestation and the quality of forest stands27. Chlorophyll is the key pigment in photosynthesis, and its content directly influences photosynthetic efficiency and the nutritional status of plants, thereby determining plant biomass and productivity28. Currently, research on the differentiation of P. yunnanensis seedlings primarily focuses on analyzing phenotypic variation29 and allometric growth among different provenances30 and the molecular mechanisms of endogenous hormone regulation of axillary bud differentiation31. Research on the impact of chlorophyll metabolism and endogenous hormone regulation on growth has primarily focused on herbaceous and broadleaf species, such as tobacco32, cotton33, Arabidopsis8, and Populus34. Currently, there is a lack of systematic studies to elucidate the intrinsic relationships between endogenous hormones, chlorophyll-related gene expression, and seedling growth in P. yunnanensis. Therefore, this study categorized P. yunnanensis seedlings into three grades (I, II, and III) based on differences in morphological characteristics, using the method of mean ± 1/2 standard deviation. This study combines analyses of seedling phenotypic traits, photosynthetic pigment content, endogenous hormone levels, and chlorophyll metabolism-related gene expression to investigate the intrinsic mechanisms of morphological differentiation and clarify the relationships among genes, hormones, and phenotypes. The goal is to provide a reference for enhancing the quality of P. yunnanensis seedlings and optimizing forest management strategies.

Materials and methods

Research location and experimental species

The seeds used in this experiment were sourced from the Dali National P. yunnanensis Breeding Base in China and were sown in the nursery of Southwest Forestry University (Kunming, N 25°04’00”, E 102°45’41”). In January 2022, after measuring the ground diameter and height of 1,200 P. yunnanensis seedlings, the seedlings were classified into three grades based on national or local nursery quality standards: Grade I ≥ H + 1/2σ, H − 1/2σ ≤ Grade II < H + 1/2σ, Grade III < H − 1/2σ. Here, H represents the average height of the seedlings, and σ is the standard deviation of this height population (Fig. 1). After classification, the seedlings were further cultivated under uniform garden conditions. The area experiences long sunshine hours and a short frost period, with an elevation of 1,945 m. It features a subtropical semi-humid plateau monsoon climate, with an average annual temperature of 14.7 °C, average annual precipitation of 883.8 mm, and an average relative humidity of 68.2%.

Measurement of seedling growth indices

In 2022, based on the seasonal growth characteristics of P. yunnanensis and the climatic conditions of the study area, the growth indices of seedlings from three grades were measured in January, March, May, August, and December35. A ruler (accurate to 0.1 cm) measured plant height and needle length. A caliper (accurate to 0.01 mm) measured the ground diameter. The number of nodes on all seedlings was counted and recorded. The root systems were scanned using an Epson root scanner to obtain images, which were then analyzed using WinRHIZO software36.

Measurement of photosynthetic pigment content in seedlings

Fresh tender needles from three grades of P. yunnanensis were collected, and according to the method described by Porra et al.’s37, 0.5 g of the sample were weighed and then ground with a small quantity of quartz sand and calcium carbonate powder. After grinding, 2 mL of 80% acetone was added and the grinding continued until the mixture became a uniform slurry. An additional 10 mL of 80% acetone was added, and the mixture was left at room temperature in the dark until it turned white. The entire mixture was then transferred to a 25 mL brown volumetric flask and made up to volume with 80% acetone. The absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 470, 645, and 663 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-16 A, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), with acetone serving as the blank control. The content of photosynthetic pigments was computed using the formulas provided by Lichtenthaler38 and Bao39:

\(\begin{aligned} & {\text{Chlorophyll a }}\left( {{\text{mg/g}}} \right){\text{ }}=({\text{12}}.{\text{72}} \times {\text{A663}} - {\text{2}}.{\text{59}} \times {\text{A645}}) \times {\text{V}}/({\text{1}}000 \times {\text{W}}) \\ & {\text{Chlorophyll b }}\left( {{\text{mg/g}}} \right){\text{ }}=({\text{22}}.{\text{88}} \times {\text{A645}} - {\text{4}}.{\text{67}} \times {\text{A663}}) \times {\text{V}}/({\text{1}}000 \times {\text{W}}) \\ & {\text{Total chlorophyll }}\left( {{\text{mg/g}}} \right){\text{ }}=({\text{2}}0.{\text{29}} \times {\text{A645}}+{\text{8}}0.0{\text{5}} \times {\text{A663}}) \times {\text{V}}/({\text{1}}000 \times {\text{W}}) \\ & {\text{Carotenoid }}\left( {{\text{mg/g}}} \right)=({\text{1}}000 \times {\text{A47}}0 - {\text{3}}.{\text{27}} \times {\text{Chlorophyll a }} - {\text{1}}0{\text{4}} \times {\text{Chlorophyll b}})/{\text{229}} \\ \end{aligned}\)

In these formulas, A470、A645 and A663 represent the absorbance at the respective wavelengths. (V) is the extract’s total volume (mL), and (W) is the fresh weight of the needles used for extraction (g).

Biomass measurement

At each time interval, 15 seedlings were randomly collected from different grades. The roots, stems, and leaves were separately measured for fresh weight using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.0001 g. After 30 min of drying at 110 °C in an oven, the samples were dried again at 80 °C until their mass remained constant. The biomass of each component was recorded, and the distribution of biomass among the components was calculated.

Plant hormone analysis

The content of plant hormones was measured using LC-MS/MS. During the rapid growth phase in March, concentrations of various cytokinins, auxins, jasmonates, salicylates, abscisic acid (ABA), and ethylene (ACC) were determined in the shoot tips of P. yunnanensis seedlings of different grades, each tested in triplicate. The cytokinins measured included isopentenyl adenine (IP), dihydrozeatin (DZ), isopentenyl adenosine (IPA), trans-zeatin (TZ), and trans-zeatin riboside (TZR). The auxins included indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), methyl indole-3-acetate (Me-IAA), and indole-3-carbaldehyde (ICAId). Jasmonates consisted of jasmonic acid (JA) and JA-Ile (N-jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine). Salicylates measured were salicylic acid (SA) and its glycosylated form, salicylic acid glucoside (SAG). Additionally, abscisic acid (ABA), and ethylene (ACC) were quantified. The hormone extraction and LC-MS/MS method are as follows: after freezing the shoot tips in liquid nitrogen and grinding into powder, 1 mL of methanol and a mixed internal standard reserve solution were added. The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and ultrasonicated for 10 min, then transferred to a metal bath to oscillate for 4 h40. After centrifugation for 10 min (12000 rpm, 4 °C) and filtration through a 0.22 μm filter, the supernatant was analyzed. Chemical analysis was performed using the ExionLC high-performance liquid chromatography system (AB Sciex, USA); data was collected using an AB SCIEX 6500 + Qtrap mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, USA) in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) model. Raw data was captured using Analyst 1.7.2 software, and results were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed using SCIEX OS V2.0.1.48692 software.

Real-time fluorescent quantitative qPCR analysis

The expression of genes linked to chlorophyll metabolism in the tips of the shoots is investigated using qRT-PCR. Total RNA is extracted from the shoot tips using a polysaccharide polyphenol plant total RNA extraction kit, and cDNA is synthesized using a reverse transcription kit, which then serves as the template for real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR. This cDNA is diluted tenfold and stored at -20 °C for subsequent use. Primers for the genes are designed using Primer 5.0 software (Supplementary Table S1), with the TUBA1 gene acting as the internal reference control. Using Taq Pro Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, real-time fluorescence quantitative expression analysis was carried out. The reaction system totaled 20 µL, including 1 µL of cDNA template, 0.4 µL each of F and R primers, 10 µL of SYBR Mix, and 8.2 µL of sterile water. The relative expression levels of the genes were calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method. Variance analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 software.

Correlation statistical analysis

To elucidate the relationships between endogenous hormone levels, chlorophyll metabolism gene expression, and seedling growth traits, this study employed https://www.omicshare.com to create a network heatmap, including the use of SPSS 24 to perform Pearson correlation analysis on gene expression and seedling growth traits to assess the linear relationships between them. Additionally, the Mantel test assessed the overall correlation between endogenous hormone levels, chlorophyll metabolism gene expression, and seedling growth traits. The Mantel test calculates the correlation coefficient (r) based on different matrices, with values ranging from − 1 to 1. An r > 0 indicates a positive correlation, with higher values denoting stronger relationships; an r < 0 indicates a negative correlation, with larger absolute values signifying more significant negative relationships; when r ≈ 0, it suggests no apparent linear correlation between the matrices. The test evaluates statistical significance using a permutation test, typically considering p < 0.05 as the threshold for significance.

Results analysis

Analysis of phenotypic traits of P. yunnanensis seedlings of different grades

Distinct differences in above-ground traits are evident among different grades of P. yunnanensis seedlings (Fig. 2). Grade I seedlings exhibit significantly greater plant height (Fig. 2B), ground diameter (Fig. 2C), and average number of branches (Fig. 2A) compared to Grades II and III. In terms of needle length, significant differences between Grade I and Grade III seedlings are only evident in January and December (Fig. 2D), with no significant differences observed during other periods. Overall, both plant height and average number of seedlings exhibit a ‘slow-fast-slow’ growth rhythm, accelerating from March, peaking around August, and then decelerating (Fig. 2A and B). In contrast, the growth in ground diameter and needle length displays a certain lag (Fig. 2C and D). Despite some fluctuations across different months, Grade I seedlings consistently maintained a significantly superior above-ground growth performance throughout the various monthly stages. Analysis of the data on the below-ground parts (Table 1) reveals that the differences are relatively limited. In January and May, the average root diameters of Grade I and Grade II seedlings were similar, and both were significantly greater than those of Grade III. By August, Grade I is markedly higher than both Grade II and Grade III, with no significant differences between the latter two. Total root volume only shows significant differences in August, with Grade I being the highest. Apart from the aforementioned time points, the root growth of seedlings across different grades does not exhibit clear gradational characteristics in most months.

Changes in growth indicators of P. yunnanensis seedlings of different grades. (A) average number of buds, (B) seedling height, (C) stem diameter, and (D) needle length. The figure displays the average value ± standard data. Distinct letters signify notable discrepancies among various grades of P. yunnanensis (p < 0.05).

Analysis of photosynthetic pigment content in seedlings of different grades

In March, the content of photosynthetic pigments generally reaches a peak, followed by a gradual decline, with levels dropping to their lowest by December (Fig. 3). From March to August, the contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids exhibit a trend of ‘Grade I > Grade II > Grade III.’ In contrast, December shows a trend of ‘Grade I < Grade II < Grade III’ (Fig. 3A, B, C and D). Additionally, the chlorophyll a/b ratio in Grade I seedlings remains consistently lower than in Grade II from January to August and is also significantly lower than in Grade III during March and May (Fig. 3E). Figure 3F shows that in January, the carotenoid/chlorophyll ratio in Grade I seedlings was significantly higher than in Grade III, with no significant difference from Grade II. There are no significant differences in this ratio among the grades in March and December. However, in May and August, the ratio for Grade II is significantly higher than for Grade I; in August, there is no significant difference compared to Grade III. Grade I seedlings have higher photosynthetic pigment levels during most of the growing season (January to August), while these indices are generally lower in December. In contrast, Grade II typically maintains intermediate levels of photosynthetic pigments, whereas Grade III initially has lower levels than the other two grades, with some indices only increasing later in the season.

Variations in the photosynthetic pigment content of different grades of P. yunnanensis seedlings. (A) Chlorophyll a content, (B) Chlorophyll b content, (C) Total chlorophyll, (D) Carotenoid content, (E) Chlorophyll a/b, and (F) Carotenoid/Chlorophyll. Each dot represents the actual data point for each sample, with black lines connecting the average values of each grade. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between grades at the same time point (p < 0.05).

Biomass investment and allocation in seedlings of different grades

Significant differences are observed in the stem, leaves, above-ground parts, non-photosynthetic organs, and overall biomass of seedlings across different grades in January and December (Table 2). No significant differences are observed in March; in May, only stem biomass shows significant variation; by August, differences emerge in the leaves, above-ground parts, and overall plant biomass. Overall, the biomass investment across different ages shows that Grade I seedlings invest the most, while Grade III invest the least.

Considering the biomass distribution among different organs (Fig. 4), significant differences in the allocation ratio of the stem are observed only in January, May, and December between Grade I and Grades II and III (Fig. 4A, C and E). Between photosynthetic (leaf) and non-photosynthetic organs, the allocation ratios in January and December are generally similar (Fig. 4A and E). During the rapid growth period in March, except for Grade II, the other grades exhibit a higher allocation ratio in photosynthetic organs (Fig. 4B). Regarding the allocation structure between above-ground and below-ground parts, seedlings exhibit relatively balanced distribution in the early stages. In contrast, the middle and late stages show a greater tendency towards above-ground parts. In summary, the biomass investment and distribution patterns of seedlings at different ages vary by grade and growth stage. Grade I focuses more on increasing biomass investment and enhancing above-ground growth.

Biomass allocation in different grades of P. yunnanensis seedlings. RB represents root biomass; SB represents stem biomass; LB represents leaf biomass; AB represents above-ground biomass; NPB represents non-photosynthetic biomass. Note: Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between grades within the same organ (p < 0.05), while different uppercase letters highlight significant variations between organs within the same grade (p < 0.05).

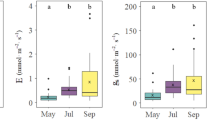

Hormone analysis

Significant differences exist among different grades of seedlings in terms of various endogenous hormone contents and ratios (Fig. 5). Compared to Grade II, Grade I seedlings exhibit 1.46 times higher levels of ABA and 1.39 times higher levels of ACC (Fig. 5E and F), while the contents of Auxins and SAs are respectively 1.10 times and 3.39 times lower (Fig. 5B and D).Compared to Grade III, Grade I seedlings show a 7.15-fold increase in JAs, a 1.48-fold increase in ABA, and a 1.16-fold increase in ACC (Fig. 5C, E, F), while their levels of CTKs, Auxins, and SAs are significantly lower (Fig. 5A, B, D).In comparisons between Grade II and Grade III, Grade II exhibits JAs and SAs levels that are 7.07 times and 1.30 times higher, respectively (Fig. 5C and D), while Grade III has 1.09 times higher CTKs and 1.20 times higher ACC levels (Fig. 5A, F).

In terms of hormone ratios, seedlings of different grades also exhibit clear differentiation (Fig. 5G–L). Grade I seedlings exhibit the highest JAs/SAs ratio (Fig. 5K) and show significant differences in most ratios compared to Grades II and III; Grade III displays higher CTKs/ABA and CTKs/JAs ratios (Fig. 5I and L).Grade I seedlings exhibit the highest JAs/SAs ratio (Fig. 5K) and show significant differences in most ratios compared to Grades II and III; Grade III displays higher CTKs/ABA and CTKs/JAs ratios (Fig. 5I and L).

Plant hormone content and ratio of P. yunnanensis seedlings of different grades. (A) Cytokinin content, (B) Auxins content, (C) Jasmonic acid content, (D) Salicylic acid content, (E) Abscisic acid content, (F) Ethylene content, (G) Auxins/Cytokinin, (H) Auxins/Abscisic acid, (I) Cytokinin/Abscisic acid, (J) Auxins/Ethylene, (K) Jasmonic acid/Salicylic acid, (L) Cytokinin/Jasmonic acid. The figure displays the average value ± standard data. Distinct letters signify notable discrepancies among various grades of P. yunnanensis (p < 0.05).

qRT-PCR gene expression analysis

Different grades of P. yunnanensis exhibit diversity in the expression of genes related to chlorophyll metabolism (Fig. 6). Compared to Grade II, Grade I exhibits significantly upregulated expression levels of GSA, CHLM, and CHLG, while Grade II shows relatively increased expression of genes such as HEMA1, CLH, and SGR. In the comparison between Grade I and Grade III, only the expression levels of CHLH and PPH show no significant changes, while most other genes exhibit significant differences. Between Grade II and Grade III, statistical differences are observed in the expression of most genes. HEMA1, GSA, CHLH, and CRD1 are higher in Grade II, while the expression levels of CLH, PAO, RCCR, and SGR are significantly upregulated in Grade III.

Metabolic pathways of chlorophyll-related gene expression in different grades of P. yunnanensis seedlings. Chlorophyll synthesis-related genes: HEMA1, GSA, CHLH, CHLM, CRD1, CHLG, CAO; Chlorophyll degradation-related genes: CLH, PPH, PAO, RCCR, SGR. The graph displays data as mean values ± standard deviation. Different letters indicate significant differences between the grades of P. yunnanensis (p < 0.05).

Analysis of the correlation between endogenous hormones, chlorophyll metabolism, and seedling indices

Pearson correlation analysis indicates that genes related to chlorophyll synthesis are significantly positively correlated with most seedling traits (Fig. 7). Among them, the CHLG and CHLM genes show a robust positive correlation with RB (r = 1, p < 0.01). CHLM is also significantly positively correlated with NPB (r = 0.998, p < 0.01) and CHLG with total root volume (r = 0.999, p < 0.01). Additionally, the CAO gene is significantly positively correlated with SD and ANB (r = 0.999, p < 0.05; r = 0.998, p < 0.05), and the GSA gene also shows significant positive correlations with NI and SD (r = 0.998, p < 0.05). Conversely, genes associated with chlorophyll degradation generally exhibit negative correlations with seedling traits. RCCR and PAO show a significant negative correlation with Total Chl (r = -1, p < 0.05), and CLH is negatively correlated with NI (r = -0.999, p < 0.05).

Further Mantel test results indicate significant associations between ABA, JAs, Auxins, CTKs, gene expression, and seedling indicators. ABA exhibits a strong positive correlation with primary root length (PRL); JAs show a significant positive correlation with Total Chl and are most notably negatively correlated with RCCR. Auxins are positively correlated with PPH expressions and negatively correlated with PRL and CHLG. Meanwhile, CTKs show the most significant negative correlation with Chl c and Chl a. Other hormones, such as SAs and ACC, also exhibit positive or negative correlations with several genes or traits, though these are not statistically significant. Overall, there is a close relationship between hormone levels, gene expression, and seedling growth traits. Hormones such as ABA, JAs, Auxins, and CTKs may play a key role in regulating the expression of chlorophyll-related genes and influencing seedling phenotypes.

Network heatmap of the correlations between hormones, chlorophyll metabolism, and seedling growth traits. The color of the lines indicates Mantel R, representing the strength of correlation, while the thickness of the lines denotes Mantel P, which is used to signify the level of significance. PRL primary root length, TRL total root length, AD average root diameter, RSA root surface area, RTV total root volume.

Discussion

As an important ecological and economic tree species in Southwest China, P. yunnanensis exhibits slow growth and distinct trait differentiation during the seedling stage, limiting its potential for afforestation and utilization27. This study found that Grade I reach peak chlorophyll content during the rapid growth period (March), coupled with a lower carotenoid/chlorophyll ratio, indicating higher photosynthetic efficiency and thus outstanding performance in above-ground growth metrics. Correspondingly, the expression levels of key synthesis genes such as GSA, CHLM, and CHLG in Grade I are significantly higher than in other grades, potentially enhancing chlorophyll synthesis by boosting the production of critical intermediates such as 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and magnesium protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester41,42. Higher levels of gene expression may enhance chlorophyll synthesis capacity and photosynthetic efficiency, thereby promoting seedling growth and development. Grade I surpasses other grades in traits such as plant height, ground diameter, and branch number. In contrast, the high expression of degradation genes such as CLH, PAO, RCCR, and SGR in Grade III accelerates chlorophyll degradation, reducing photosynthetic capacity and consequently limiting growth43,44. This indicates that differences at the genetic level are directly reflected in the seedlings’ photosynthetic performance and above-ground morphological indices.

In environments with limited resources, plants optimize their survival and reproductive capacity by adjusting biomass allocation. The above-ground parts of P. yunnanensis seedlings, such as stems and leaves, which serve as the principal organs for energy acquisition through photosynthesis, exhibit a significant growth advantage in competing for light resources45,46. Conversely, the root system, primarily responsible for the absorption of water and nutrients, often shows less significant growth variations. However, the growth strategies of the primary and lateral roots vary across different growth stages47. Under the cold conditions and low soil temperatures of January, the growth of the primary root is inhibited, while some lateral roots may maintain their earlier growth state, causing the primary root length to be shorter than the total root length initially. However, as temperatures rise, the growth of P. yunnanensis seedlings accelerates, with the primary root rapidly extending to access deeper water sources and nutrients. In contrast, the growth rate of lateral and other roots is relatively slower, leading to the primary root length gradually surpassing the total root length. In this study, Grade I responded more quickly during the rapid growth period in March, exhibiting earlier primary root growth than other grades. The primary root growth in other grades typically accelerated significantly from May. By December, as plants enter a dormant phase, most of the delicate and transient roots diminish or even disappear due to reduced water, temperature, and carbon allocation, resulting in a sharp decline in total root volume48.

Endogenous hormones play a key role in regulating the growth process of seedlings49,50. This study shows that hormone levels of ABA, JAs, and ACC are significantly elevated in Grade I, potentially enhancing stress tolerance and photoprotection to sustain rapid growth51,52,53,54. Conversely, Grades II and III, which have higher levels of Auxins and SAs, may have advantages in root growth and pathogen defense, but this appears to inhibit above-ground growth to some extent18,55,56. From a genetic perspective, Mantel tests and correlation analyses demonstrate significant associations between these hormones and chlorophyll metabolism-related genes. For instance, JAs are positively correlated with CHLM and CHLG, as well as with total chlorophyll content, suggesting that JAs may promote chlorophyll accumulation by upregulating the expression of chlorophyll synthesis genes57,58,59. Furthermore, high levels of Auxins are positively correlated with specific degradation genes, suggesting that Auxins may have a negative regulatory effect on photosynthetic pigment metabolism60. Excessive levels of CTKs are significantly negatively correlated with Chl Cc and Chl a, potentially exerting adverse effects61. This indicates that hormones and gene expression form a synergistic or antagonistic network in seedling photosynthesis and growth development. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of the role of plant hormones in natural and managed forest ecosystems, providing a scientific basis for future forestry management and breeding.

Beyond individual hormones, complex synergistic and antagonistic relationships exist among various hormones, which are crucial for regulating seedlings’ growth and defense responses51,62,63,64. This study observed that an increase in JAs/ACC is often accompanied by a decrease in SAs and a rise in ABA levels, supporting the synergistic role of JAs with ACC and ABA in plant defense64. The defense pathway mediated by SAs is antagonistic to the ET/JAs pathway, reflecting how plants rely on different hormonal pathways to regulate their defense strategies when faced with various pathogen attacks63. In sugarcane, a high Auxins/CTKs ratio promotes root growth, while a low ratio favors above-ground growth, highlighting the role of hormonal balance in plant morphogenesis65. Similarly, the JAs/SAs ratio is closely linked to plant defense responses; a high JAs/SAs ratio enhances resistance to insect pests66, while a low ratio favors defense against pathogens67. The dynamic balance of these hormones finely controls photosynthetic efficiency, nutrient allocation, and overall growth by regulating transcription levels and activating specific signaling pathways68. Adjusting these hormonal ratios through genetic improvements or management practices can enhance plant growth performance and yield, although the specific mechanisms still require further investigation.

Conclusion

This study focuses on different grades of P. yunnanensis seedlings, exploring variations in their growth characteristics, photosynthetic pigment content, endogenous hormone levels, and related gene expression. It reveals the synergistic regulatory mechanisms between chlorophyll metabolism and endogenous hormones during the growth process of seedlings. Grade I exhibits high expression of chlorophyll synthesis genes and optimal endogenous hormone levels, facilitating efficient photosynthesis and superior growth performance. Conversely, in lower-grade seedlings, high expression of chlorophyll degradation genes accelerates chlorophyll breakdown, limiting their photosynthetic capacity. Variations in hormone levels, particularly changes in ABA, JAs, Auxins, and CTKs, significantly influence the growth strategies and adaptability of seedlings. For afforestation and forest management, the regulatory network of genes, hormones, and phenotypes reveals critical factors influencing early seedling growth. Future strategies could involve precisely regulating key gene expression and optimizing endogenous hormone levels to promote ideal trait expression in seedlings, enhance their environmental adaptability, and thereby improve the productivity and ecological benefits of managed forests.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article, and the gene sequences involved are from the biological project PRJNA1065384.

References

Kim, S. et al. Arabidopsis chlorophyll biosynthesis: an essential balance between the methylerythritol phosphate and tetrapyrrole pathways. Plant. Cell. 25, 4984–4993. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.119172 (2013).

Reinbothe, C. et al. Chlorophyll biosynthesis: spotlight on protochlorophyllide reduction. Trends Plant. Sci. 15, 614–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2010.07.002 (2010).

Croce, R. & van Amerongen, H. Natural strategies for photosynthetic light harvesting. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.1555 (2014).

Matters, G. L. & Beale, S. I. Structure and light-regulated expression of the gsa gene encoding the chlorophyll biosynthetic enzyme, glutamate 1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Mol. Biol. 24, 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00023558 (1994).

Tanaka, R. & Tanaka, A. Tetrapyrrole biosynthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 58, 321–346. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105448 (2007).

Li, Q. et al. A chlorophyll a oxygenase 1 gene ZmCAO1 contributes to grain yield and waterlogging tolerance in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 3155–3167. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erab059 (2021).

Harpaz-Saad, S. et al. Chlorophyllase is a rate-limiting enzyme in chlorophyll catabolism and is posttranslationally regulated. Plant. Cell. 19, 1007–1022. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.107.050633 (2007).

Schelbert, S. et al. Pheophytin Pheophorbide Hydrolase (Pheophytinase) is involved in Chlorophyll Breakdown during Leaf Senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 21, 767–785. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.108.064089 (2009).

Pružinská, A., Tanner, G., Anders, I., Roca, M. & Hörtensteiner, S. Chlorophyll breakdown: pheophorbide a oxygenase is a Rieske-type iron–sulfur protein, encoded by the accelerated cell death 1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 15259–15264. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2036571100 (2003).

Hortensteiner, S. Chlorophyll degradation during senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 57, 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105212 (2006).

Wüthrich, K. L., Bovet, L., Hunziker, P. E., Donnison, I. S. & Hörtensteiner, S. Molecular cloning, functional expression and characterisation of RCC reductase involved in chlorophyll catabolism. Plant J. 21, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00667.x (2000).

Sakuraba, Y. et al. STAY-GREEN and chlorophyll catabolic enzymes interact at light-harvesting complex II for chlorophyll detoxification during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant. Cell. 24, 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.111.089474 (2012).

Xue, S. et al. MdSGR2 negatively regulates chlorophyll degradation in Apple. Horticulturae 10, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10050439 (2024).

Elliott, A. M. The influence of certain plant hormones on growth of protozoa. Physiological Zool. 11, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/physzool.11.1.30151438 (1938).

Liu, X., Li, Y. & Zhong, S. Interplay between light and plant hormones in the control of Arabidopsis seedling chlorophyll biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01433 (2017).

Pieterse, C. M., Van der Does, D., Zamioudis, C., Leon-Reyes, A. & Van Wees, S. C. Hormonal modulation of plant immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 28, 489–521. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154055 (2012).

Scartazza, A. et al. The role of Euglena gracilis paramylon in modulating xylem hormone levels, photosynthesis and water-use efficiency in Solanum lycopersicum L. Physiol. Plant. 161, 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12611 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Rice GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR7 modulates Plant Architecture through regulating GA and Indole-3-Acetic acid metabolism. Plant. Physiol. 184, 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.20.00302 (2020).

Malbeck, J., Machchov, I. & Nebesov, J. Three-dimensional reconstruction of anomalous chloroplasts in transgenic ipt tobacco. Planta 223, 659–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-005-0119-6 (2006).

Werner, T. et al. Cytokinin deficiency causes distinct changes of sink and source parameters in tobacco shoots and roots. J. Exp. Bot. 59, 2659–2672. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ern134 (2008).

Su, L. et al. Carotenoid accumulation during tomato fruit ripening is modulated by the auxin-ethylene balance. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0495-4 (2015).

Hirosawa, Y. et al. Salicylic acid acts antagonistically to plastid retrograde signaling by promoting the accumulation of photosynthesis-associated proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 62, 1728–1744. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcab128 (2021).

Tan, X. et al. Association of BrERF72 with methyl jasmonate-induced leaf senescence of Chinese flowering cabbage through activating JA biosynthesis-related genes. Hortic. Res. 5, 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-018-0028-z (2018).

Terfa, M. T., Olsen, J. E. & Torre, S. Blue light improves stomatal function and dark-induced closure of rose leaves (Rosa x Hybrida) developed at high air humidity. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1036. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01036 (2020).

Chen, J., Wu, Z., Yu, Z., Ma, H. & Wu, J. First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma asteris’ associated with witches’-broom disease of Pinus yunnanensis in China. Plant. Dis. 107, 3276. https://doi.org/10.1094/PDIS-04-23-0732-PDN (2023).

Qiu, J., Chen, L., Yi, X. & Li, M. The complete chloroplast genome of Pinus Yunnanensis Franchet (Pinaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 4, 2600–2601. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802359.2019.1565929 (2019).

Liu, Z., Gao, C., Li, J., Miao, Y. & Cui, K. Phenotypic Diversity Analysis and Superior Family Selection of Industrial Raw Material Forest species-Pinus yunnanensis Franch. Forests 13, 618. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13040618 (2022).

Croft, H. et al. Leaf chlorophyll content as a proxy for leaf photosynthetic capacity. Glob Chang. Biol. 23, 3513–3524. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13599 (2017).

Qibo, W. et al. Variation of growth traits and allometric growth of seedlings of Pinus yunnanensis from different provenances. J. Southwest. Forestry Univ. 44, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.11929/j.swfu.202304 (2024).

Lu, Z. et al. Endogenous phytohormone and transcriptome analysis provided insights into Seedling Height Growth of Pinus yunnanensis. Forests 15, 489. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15030489 (2024).

He, H., Xu, J., Cai, N. & Xu, Y. Analysis of the molecular mechanism endogenous hormone regulating axillary bud development in Pinus yunnanensis. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-05819-6 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Effect of chlorophyll biosynthesis-related genes on the leaf color in Hosta (Hosta plantaginea Aschers) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L). BMC Plant Biol. 21, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02805-6 (2021).

Yang, K. et al. Morphological and physiological mechanisms of melatonin on delaying drought-induced leaf senescence in cotton. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 7269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24087269 (2023).

An, J., Wei, X. & Huo, H. Transcriptome analysis reveals the accelerated expression of genes related to photosynthesis and chlorophyll biosynthesis contribution to shade-tolerant in Phoebe Bournei. BMC Plant Biol. 22, 268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-022-03657-y (2022).

XIE, M., YAO, Y. & PENG, Q. Characterization of Seasonal Changes in Low-Latitude Plateau Climate–Taking Kunming Dali in Yunnan as an Example. Journal of Tropical Meteorology (1004–4965) 39, 171–182. (2023). https://doi.org/10.16032/j.issn.1004-4965.2023.017

Fan, C. et al. Response of root and root hair phenotypes of cotton seedlings under high temperature revealed with RhizoPot. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1007145. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1007145 (2022).

Porra, R. J., Thompson, W. A. & Kriedemann, P. E. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenergetics. 975, 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80347-0 (1989).

Hartmut, K. & Alan, R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Analysis 4, 142–196. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst0110591 (1983).

Bao, W., Leng, L. J. C. & J. A. E. B. determination methods for photosynthetic pigment content of bryophyte with special relation of extracting solvents. 11, 235–237, (2005).

Li, E. et al. The roles of hormone signals involved in Rhizosphere pressure response induce corm expansion in Sagittaria trifolia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 12345. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24151234 (2023).

Beale, S. I. Green genes gleaned. Trends Plant. Sci. 10, 309–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2005.05.005 (2005).

Kobayashi, K. & Masuda, T. in Advances in Botanical Research Vol. 91 133–161Elsevier, (2019).

Gan, L., Han, L., Yin, S. & Jiang, Y. Chlorophyll metabolism and gene expression in response to submergence stress and subsequent recovery in Perennial Ryegrass accessions Differing in Growth habits. J. Plant Physiol. 251, 153195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153195 (2020).

Hu, X., Gu, T., Khan, I., Zada, A. & Jia, T. Research Progress in the interconversion, turnover and degradation of Chlorophyll. Cells 10, 3134. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10113134 (2021).

Freschet, G. T., Violle, C., Bourget, M. Y., Scherer-Lorenzen, M. & Fort, F. Allocation, morphology, physiology, architecture: the multiple facets of plant above- and below-ground responses to resource stress. New. Phytol. 219, 1338–1352. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15225 (2018).

Wang, Y., Donovan, L. A. & Temme, A. A. Plasticity and the role of mass-scaling in allocation, morphology, and anatomical trait responses to above- and belowground resource limitation in cultivated sunflower (Helianthus annuus L). Plant. Direct. 4, e00274. https://doi.org/10.1002/pld3.274 (2020).

Sili, C. et al. Analysis of root morphological characteristics of Pinus yunnanensis seedlings at different stump-ages. J. Zhejiang A&F Univ. 41, 322–332. https://doi.org/10.11833/j.issn.2095-0756.20230466 (2024).

SHI, J. L., YANG, S., ZHUANG, C. & GU, K. Effect of Nitrogen Application on Soil Nitrate Nitrogen Content, Root Growth and Nitrogen utilization of Winter in Rice-Wheat Rotation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 26, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.13870/j.cnki.stbcxb.2012.05.054 (2012).

Piotrowska, A. & Bajguz, A. Conjugates of abscisic acid, brassinosteroids, ethylene, gibberellins, and jasmonates. Phytochemistry 72, 2097–2112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.08.012 (2011).

Zhang, W. et al. Grain filling characteristics and their relations with endogenous hormones in large- and small-grain mutants of Rice. PLoS One. 11, e0165321. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165321 (2016).

Chen, H., Bullock, D. A. Jr., Alonso, J. M. & Stepanova, A. N. To fight or to Grow: the Balancing Role of Ethylene in Plant Abiotic stress responses. Plants (Basel). 11, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11010033 (2021).

Hou, Y. et al. Dissecting the effect of ethylene in the transcriptional regulation of chilling treatment in grapevine leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 196, 1084–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.03.015 (2023).

Jia, D. et al. Abscisic acid activates transcription factor module MdABI5-MdMYBS1 during carotenoid-derived apple fruit coloration. Plant. Physiol. 195, 2053–2072. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiae188 (2024).

Sun, L. R., Wang, Y. B., He, S. B. & Hao, F. S. Mechanisms for Abscisic Acid Inhibition of Primary Root Growth. Plant. Signal. Behav. 13, e1500069. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592324.2018.1500069 (2018).

Kononowicz, H. Cytological study of inhibitory effects of IAA on the root growth in the Pinus silvestris. Folia Histochem. et Cytochem. 16, 109–122 (1978).

Vinod, K. & Sabah, A. Plant defense against pathogens: the role of salicylic acid. Res. J. Biotechnol. 13, 97–103 (2018).

Qiu, X. et al. Effects of exogenous methyl jasmonate on the synthesis of endogenous jasmonates and the regulation of photosynthesis in citrus. Physiol. Plant. 170, 398–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.13170 (2020).

Salavati, J., Fallah, H. & Niknejad, Y. Barari Tari, D. Methyl jasmonate ameliorates lead toxicity in Oryza sativa by modulating chlorophyll metabolism, antioxidative capacity and metal translocation. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 27, 1089–1104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-021-00993-5 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Effects of Preharvest Methyl Jasmonate and Salicylic Acid treatments on growth, Quality, Volatile Components, and Antioxidant Systems of Chinese Chives. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 767335. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.767335 (2022).

Luo, W. G. et al. Auxin inhibits chlorophyll accumulation through ARF7-IAA14-mediated repression of chlorophyll biosynthesis genes in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1172059. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1172059 (2023).

Hewelt, A., Prinsen, E., Schell, J., Van Onckelen, H. & Schmülling, T. Promoter tagging with a promoterless ipt gene leads to cytokinin-induced phenotypic variability in transgenic tobacco plants: implications of gene dosage effects. Plant J. 6, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.1994.6060879.x (1994).

Ge, W. et al. Changes in endogenous hormone contents during seed germination of Anemone Rivularis var. Flore-minore. Global Ecol. Conserv. 24, e01200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01200 (2020).

Li, N., Han, X., Feng, D., Yuan, D. & Huang, L. J. Signaling Crosstalk between Salicylic Acid and Ethylene/Jasmonate in Plant Defense: do we understand what they are whispering? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20030671 (2019).

Wang, J., Song, L., Gong, X., Xu, J. & Li, M. Functions of Jasmonic Acid in Plant Regulation and response to Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21041446 (2020).

Zhou ChuanFeng, Z. C. & Li YangRui, L. Y. & Yang LiTao, Y. L. Changes of IAA and CTK in sugarcane sprayed with ethephon at early tillering stage. (2007).

Zhang, P. J., Huang, F., Zhang, J. M., Wei, J. N. & Lu, Y. B. The mealybug Phenacoccus Solenopsis suppresses plant defense responses by manipulating JA-SA crosstalk. Sci. Rep. 5, 9354. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09354 (2015).

Ding, P. & Ding, Y. Stories of salicylic acid: a Plant Defense hormone. Trends Plant. Sci. 25, 549–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2020.01.004 (2020).

Wilkinson, S., Kudoyarova, G. R., Veselov, D. S., Arkhipova, T. N. & Davies, W. J. Plant hormone interactions: innovative targets for crop breeding and management. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 3499–3509. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers148 (2012).

Funding

This work was funded by the Yunnan Provincial First-Class Discipline Construction Fund for Forestry at Southwest Forestry University (LXXK-2024Z07); Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (202401BD070001-023); Yunnan Province Ten Thousand People Plan Youth Top Talent Project Funding (YNWR-QNBJ-2019-075); Yunnan Graduate Tutor Team Building Project (2022-97).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruilian Li conceptualized the study, processed the data, designed the experiment and wrote the original draft. Qibo Wang processed the data and analyzed results. Yulan Xu collected data, provided resources and edited the manuscript. Nianhui Cai analyzed results. Lin Chen and Sunling Li edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, R., Wang, Q., Li, S. et al. Study on the growth characteristics of Pinus yunnanensis seedlings based on hormonal regulation and chlorophyll metabolism. Sci Rep 15, 6195 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90589-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90589-w