Abstract

Domestic animals can harbor a variety of enteric unicellular eukaryotic parasites (EUEP) with zoonotic potential that pose risks to human health. The aim of this study was to evaluate the occurrence and genetic diversity of EUEP of zoonotic relevance in domestic animals in Iran. Faecal samples were collected from cattle, sheep, camels, goats, donkeys, horse, and dogs. A real-time PCR was performed to detect the parasites, followed by sequence-based genotyping analyses on isolates that tested positive for Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Giardia duodenalis, and Blastocystis sp.. Overall, 53 out of 200 faecal samples (26.5%, 95% CI 20.5–33.2) were positive for one or more EUEP. Enterocytozoon bieneusi was found in 23.8%, 12.0%, 26.1%, and 13.3% of cattle, sheep, goats, and camels, respectively. Giardia duodenalis was identified in 19.3% of cattle and 6.7% of camels. Blastocystis sp. was detected in 5.7% of cattle and 16.7% of camels. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes macaque1, J, BEB6, and CHG3 were identified in 3.7% (1/27), 3.7% (1/27), 44.4% (12/27), and 48.2% (13/27) of the isolates, respectively. Giardia duodenalis assemblage B and Blastocystis subtype 10 were identified in one cattle and one camel isolate, respectively. These findings suggest that domestic animals could serve as potential reservoirs for EUEP of zoonotic relevance and might play a significant role in transmitting these parasites to humans and other animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Giardia duodenalis, Blastocystis sp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Cryptosporidium spp. are common enteric unicellular eukaryotic parasites (EUEP) that infect humans and other animals1,2,3. Giardia duodenalis causes clinical manifestations that vary from asymptomatic cases to acute diarrhea and malabsorption4. Blastocystis sp. is most frequently found in asymptomatic hosts, and its pathogenicity profile remains unclear5. Cryptosporidium spp. and E. bieneusi can opportunistically cause disseminated infections in immunocompromised individuals such as AIDS patients6.

The infections are acquired by ingesting cysts, oocysts, or spores in food or water that has been contaminated by faeces7,8. Human infections with G. duodenalis can lead to the excretion of up to 2 × 105 cysts per gram of faeces7. Infected animals, especially young ones, can shed up to 107 Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts per gram of faeces at the peak of the infection9. This demonstrates the significant contribution of livestock to the environmental load of infective (oo)cysts, which can cause waterborne10 and foodborne11 diarrhea outbreaks in humans worldwide.

Accurate identification of EUEP genotypes requires the use of molecular diagnostic tools, which reveal genetic diversity and zoonotic transmission routes. Techniques such as multilocus sequence typing and PCR-based methods have significantly enhanced our understanding of the prevalence and transmission dynamics of the parasites3. These parasites exhibit pronounced intraspecific genetic diversity, reflected in marked differences in host range and specificity, potential for zoonotic transmission, and pathogenicity2,3,12. Giardia duodenalis encompasses eight genetic assemblages (A-H). Assemblages A and B are commonly identified in humans and other mammalian hosts, whereas C to H are considered to be host-specific, predominantly infecting canids (C and D), ungulates (E), felids (F), rodents (G), and marine pinnipeds (H)13. Despite being ‘host-adapted’, assemblages C, D, E, and F have also been reported in humans14. Currently, Cryptosporidium comprises at least 46 taxonomically valid species, among which, over 20 have been identified in humans3,15,16,17. Cryptosporidium hominis and C. parvum are responsible for 95% of human cases of cryptosporidiosis, followed by C. meleagridis, C. felis, and C. canis15,18. Eight species have been reported in ungulates, with C. parvum and C. andersoni being the most prevalent3,19,20. Cattle can also carry C. hominis, which could be responsible for a number of human Cryptosporidium infections21. To date, nearly 600 distinct genotypes of E. bieneusi have been identified and categorized into 11 major phylogenetic groups, among which 9 zoonotic genotypes (A, BEB4, BEB6, D, EbpA, EbpC, I, J, and Type IV) have been found circulating in domestic animals22. Of the 40 identified subtypes of Blastocystis sp. (ST1-ST17, ST21, ST23-ST44)11,23,24,25,26, 12 subtypes (ST1-ST10, ST12, and ST14) have been recognized as zoonotic27,28,29.

Domestic animals harbor a wide variety of EUEP that may be transmitted to humans through faeces. It is therefore essential to understand the occurrence and genetic diversity of these parasites to investigate their zoonotic potential. In Iran, there is a scarcity of data on the molecular epidemiology of EUEP of zoonotic relevance in animal populations, with most of the studies relying on conventional light microscopy for screening, and only a limited number assessing the occurrence and genetic diversity (Table 1). The present study was conducted with the aim of investigating the occurrence, genetic diversity, and zoonotic potential of Blastocystis sp., G. duodenalis, E. bieneusi, and Cryptosporidium spp. in various domestic animals in southeastern Iran.

Results

Microscopic detection of G. duodenalis cysts

In the initial examination of the faecal samples using conventional microscopy, 1.5% (3 of 200, 95% CI 0.3–4.3) were found to be positive for G. duodenalis cysts, originating from two sheep and one goat.

Molecular detection of the parasites

Of the 200 faecal samples analyzed, 53 (26.5%, 95% CI 20.5–33.2) tested positive for one or more EUEP, and 147 (73.7%) were negative by qPCR (Tables 2, 3). Single infections were found in 20.5% (41 of 200), and co-infections by two and three parasite species were detected in 5.5% (11 of 200) and 0.5% (1 of 200), respectively (Table 3), resulting in an overall prevalence of 33.0% (66 of 200, 95% CI 26.5–39.9) (Table 2). The overall prevalences of Blastocystis sp., E. bieneusi, and G. duodenalis in animals were 5.0% (95% CI 2.4–9.0), 18.5% (95% CI 13.4–24.6), and 9.5% (95% CI 5.8–14.4), respectively. All analyzed animal faecal samples were negative for Cryptosporidium spp.. Blastocystis sp. was found in 5.7% of cattle (5 of 88, 95% CI 1.9–12.8) and 16.7% of camels (5 of 30, 95% CI 5.6–34.7). The prevalence rates of E. bieneusi were 23.8% (21 of 88, 95% CI 15.4–34.1), 12.0% (6 of 50, 95% CI 4.5–24.3), 26.1% (6 of 23, 95% CI 10.2–48.4), and 13.3% (4 of 30, 95% CI 3.7–30.7), respectively, in cattle, sheep, goats, and camels. Giardia duodenalis was identified in 19.3% of cattle (17 of 88, 95% CI 11.7–29.1) and 6.7% of camels (2 of 30, 95% CI 0.8–22.0) (Table 2). Statistical analysis revealed a lack of agreement (κ-value: -0.027 [95% CI -0.053 to -0.000]) between microscopy and qPCR for the detection of G. duodenalis cysts (Table 4).

Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotyping

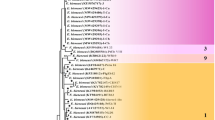

Of the 37 faecal DNA samples (4 camels, 21 cattle, 6 goats, 6 sheep) with Ct values ≤ 35, 27 (72.9%) were successfully amplified at the ITS locus using nested-PCR analysis (Table 3). The sequence analysis identified the presence of genotypes J in 3.7% (1 of 27), BEB6 in 44.4% (12/27), CHG3 in 48.2% (13 of 27), and macaque1 in 3.7% (1 of 27) of the samples. The genotype CHG3 was the most common, found in one camel (7.7%), five cattle (38.5%), two sheep (15.4%), and five goats (38.5%). The genotype BEB6 was identified in nine cattle (75.0%), two camels (16.7%), and one goat (8.3%). The genotypes J and macaque1 were each observed in a single sample from cattle and camel, respectively (Table 3). Figure 1 illustrates the phylogenetic tree constructed using representative sequences from the eleven E. bieneusi ITS groups and genotypes identified to date. The genotypes CHG3, J, BEB6, and macaque1 were distinctly classified into three genetic groups: 2c, 2b, 2c, and 6, respectively.

Phylogenetic relationship among Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes revealed by a maximum likelihood analysis of the partial ITS gene. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrapping values over 70% using 1,000 replicates. The red animal silhouettes indicate the nucleotide sequences generated in the present study. The filled coloured circles indicate the nucleotide sequences of genotypes. Human and animal sequences retrieved from GenBank were included in the analysis for comparative purposes.

Blastocystis sp. subtyping

Among the 10 faecal DNA samples with Ct values ≤ 35 obtained from 5 camels and 5 cattle, 9 (90.0%) were successfully amplified at the ssu rRNA locus using nested-PCR analysis. The sequence analysis identified ST10 in a single camel sample (1 of 9, 11.1%) (Table 3). The phylogenetic analysis revealed a clear distinction among Blastocystis sp. subtypes, which matched the classification obtained from BLAST query, in comparison to the reference subtype sequences available in GenBank (Fig. 2). According to homology analysis, the only camel-derived ST10 sequence (PQ211066) shared 100% and 99.82% identities with those from cattle in China (OL981840) and from goats in Colombia (MZ265404), respectively.

Phylogenetic relationship among Blastocystis sp. subtypes revealed by a maximum likelihood analysis of the partial the ssu rRNA gene. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrapping values over 70% using 1,000 replicates. The red animal silhouette indicates the nucleotide sequence generated in the present study. Human and animal sequences retrieved from GenBank were included in the analysis for comparative purposes.

Giardia duodenalis genotyping

Among the 19 qPCR-positive samples (2 camels, 17 cattle) analyzed by nested-PCR analysis, one cattle isolate (5.3%) that produced an amplicon of the expected size in gdh-PCR was successfully genotyped and classified into zoonotic assemblage B by sequence analysis (Table 3). The phylogenetic analysis consistently grouped the partial nucleotide sequences of the gdh locus into G. duodenalis assemblages A to H, as well as G. ardeae, with strong support indicated by a posterior probability of 100 (Fig. 3).

Phylogenetic relationship among Giardia duodenalis assemblages revealed by a maximum likelihood analysis of the partial the gdh gene. Numbers on branches are percent bootstrapping values over 70% using 1,000 replicates. The red animal silhouette indicates the nucleotide sequence generated in the present study. Human and animal sequences retrieved from GenBank were included in the analysis for comparative purposes.

Discussion

Domestic animals can be infected with a wide range of parasitic pathogens that can also infect humans. It may not be surprising that around 243 out of the 616 pathogens (39%) known to infect livestock are also capable of infecting humans53. Domestic animals with free access to outdoor environments may be at an elevated risk of exposure to pathogens and could serve as neglected reservoirs for zoonotic agents. This study focused on the molecular diversity of Blastocystis sp., E. bieneusi, and G. duodenalis in domestic animals in Iran, particularly assessing their zoonotic potential. There is a lack of molecular data regarding the studied parasite species in animal populations of Iran. The study complements information previously shared by our research group on the epidemiology of gastrointestinal parasites of veterinary health relevance in domestic animal species54.

In the present study, 26.5% of the samples tested positive for one or more EUEP using qPCR. In the only comparable molecular-based study on Iranian livestock populations to date, an overall prevalence of 46.2% (80/173) was found in the provinces of Kordestan and Lorestan44.

The initial microscopic screening of the samples for G. duodenalis cysts revealed an overall prevalence rate of 1.5%, while the subsequent molecular screening detected the parasite at a higher prevalence rate of 9.5%. This difference was predictable, as qPCR demonstrates superior diagnostic performance compared to conventional microscopy due to its higher sensitivity and specificity, enabling the detection of low quantities of cysts and reducing false positives55. Furthermore, unlike microscopy, which relies on the technician’s skill and experience for cyst identification—leading to subjective interpretation and variability in results—qPCR provides objective measurements that significantly minimize this variability.

Interestingly, none of the microscopy-positive samples for G. duodenalis were detected by qPCR, and the opposite was also true (κ-value: -0.027). The difference in diagnostic accuracy between the two screening techniques being compared is supported by the discrepancies noted in previous comparative studies56,57. The amount of specimen analyzed may have influenced the results, as the amount of faeces analyzed by microscopy is 100–200 mg. For qPCR, 1.7–2.5 mg of faeces is analysed, assuming that 1 mg equals 1 µL56.

Microscopy-based studies have reported G. duodenalis prevalences ranging from 0.6% to 40.0% among domestic animal populations in Iran (Table 1). In the only molecular-based study examining the presence of G. duodenalis in ruminant animals in Iran, prevalences of 6.2% (12/192), 5.0% (5/100), and 4.2% (8/192) were reported in sheep, goats, and cattle, respectively, in Yazd Province31. In the present study, the characterized G. duodenalis isolate was identified as belonging to the zoonotic assemblage B. In the study area, a rural lifestyle is predominant, with many households keeping ruminant animals in the courtyards of their mud-walled homes, likely contributing to the cross-transmission of zoonotic assemblage B between animals and humans. This finding contrasts with the existing evidence in the country (Table 1), where assemblages A and E have previously been identified in hoofed animals30,31,58, and assemblages A, C, and D in dogs33,34. Many studies have shown that assemblage E is the predominant assemblage found in cattle worldwide, followed by assemblage A, and less commonly, assemblage B14. Furthermore, three studies have identified assemblages C, D, and F in cattle from the UK, the USA, and Spain59,60,61. In a study on cattle in Scotland62, assemblage B was found to be the second most prevalent (18.2%) following assemblage E (77.2%) at the bg locus. Remarkably, some assemblage B isolates of bovine origin had 100% sequence identity with a human isolate (KX960128) from Spain62. In the current study, the assemblage B isolate was found to have sequence identities of 99.46% and 99.43% with human isolates from Iran (LC184469) and Japan (LC507387), respectively. This suggests that cattle may act as a reservoir for this assemblage, which could have potential public health consequences.

E. bieneusi was found in 13.3% of camels, 23.8% of cattle, 12.0% of sheep, and 26.1% of goats, with an overall prevalence rate of 18.5%. Enterocytozoon bieneusi infections in livestock populations in Iran have previously been reported in the range of 5.1–34.4% by PCR (Table 1). Molecular studies in different parts of the world have shown that infection rates vary from 2.7% to 91.2%63,64,65,66,67,68,69. The variations in prevalence rates likely reflect changes in epidemiological scenarios, influenced by differences in parasite genotypes, host populations, environmental conditions, and transmission routes. Our molecular analyses identified the E. bieneusi genotypes CHG3, J, BEB6, and macaque1 circulating in the ruminant populations studied. This finding aligns with existing evidence from the country, where E. bieneusi genotype BEB6 was previously identified in cattle and sheep from Lorestan and Kordestan Provinces44, and genotype J was found in cattle from Ardabil and Fars Provinces51,70. The genotypes CHG3 and BEB6 were the most predominant types and displayed a broader animal host range than other genotypes, which aligns with findings from various studies around the world71,72,73. The genotypes CHG3, BEB6, and macaque1 were detected in camels. Molecular investigations of E. bieneusi in camelids have thus far been limited to six studies conducted in Algeria, Australia, China, and Peru74,75,76,77,78,79. The presence of zoonotic genotypes in ruminants70, along with sporadic infections in humans from ruminant-adapted genotypes (CHG3, J, and BEB6)80,81, highlights the significance of these livestock animals in the zoonotic transmission of E. bieneusi. Recently, the genotype BEB6 has been identified in raw milk from dairy cattle and sheep82, increasing concerns about its potential zoonotic transmission to humans. Several studies have also reported genotype J in various host species, including cattle, yaks, goats, Tibetan sheep, Przewalski’s gazelle, birds, and humans83,84,85,86,87.

Blastocystis sp. was found in 16.7% of camels and 5.7% of cattle, with an overall prevalence rate of 5.0%. In a recent study conducted in Iran48, a prevalence of 12% (18/150) was reported in dromedary and Bactrian camels in Ardabil Province. Blastocystis sp. infections in Iranian bovine populations have been previously documented to range from 6.0 to 50.6% using PCR (Table 1). In this study, ST10 was identified in one camel sample, which aligns with existing evidence in Iran, where ST10 was previously detected in 50.0% of camels (9/18) in Ardabil Province48. In a recent study conducted among zoo animals in China, 18.2% (2/11) of alpacas were found to be infected with ST1088. Although ST10 is commonly isolated from ruminant livestock45,47,48,48, two recent studies have reported the presence of this animal-specific subtype among human populations from Thailand and Senegal89,90, giving the impression of zoonotic transmission.

The study found no Cryptosporidium spp. in the animal populations examined, which contrasts with previous reports from Iran. Cryptosporidium oocysts were microscopically identified in 1.5% to 63.7% of animal faecal samples (Table 1). The failure to identify Cryptosporidium spp. in the current study could be attributed to the small sample sizes, especially for canines and equines.

The main strength of this study is the reporting of molecular epidemiological data on EUEP infections in domestic animals from a geographical region in Iran, where such information was previously lacking. However, the study also has limitations that might have compromised the accuracy of some of the results obtained. First, negative samples examined with direct smear were not subjected to further testing using permanent staining techniques (e.g., trichrome and modified acid-fast staining methods). Second, the sample size for each animal was limited, particularly for canines and equines, which is why we did not find any of the EUEP in these animals.

Conclusion

This is the first study investigating the molecular epidemiology of EUEP in southeastern Iran. The presence of zoonotic genotypes of E. bieneusi (CHG3, BEB6, and J), G. duodenalis (assemblage B) and Blastocystis sp. (subtype 10) in ruminant animals in this study could contribute to the understanding of the transmission dynamics of these parasites among animals and humans who are in close contact with livestock. However, any conclusions about zoonotic transmission should be drawn with caution, as the presence of similar or different genotypes/subtypes dispersed across various sources does not, by itself, provide conclusive evidence that zoonotic transmission is occurring or not.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from the owners of the animals involved in this study. Samples were collected during veterinary medical care or checkups. All experimental protocols were approved by the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, and all procedures performed in this study adhered to the ethical standards (IR.SBMU.RIGLD.REC.1402.011) set forth by the Ethical Review Committee of the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Furthermore, all methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and all authors complied with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Study area

This study was conducted in Iranshahr County, located in the central area of Sistan and Baluchestan province in southeastern Iran4,54. The area has a low density of domestic animals, with local families usually raising up to five cattle in a semi-intensive manner in their backyards. Ruminants graze freely in hay fields during the day and are kept at night in small, partially covered structures.

Sample collection

A total of 200 faecal samples were collected between May and September 2022 from various domestic animal species, including 88 cattle, 55 sheep, 30 camels, 23 goats, 5 donkeys, 3 stray dogs, and one horse. Individual faecal samples (10–20 g of faeces per animal) were taken directly from the rectum of ruminant animals with sterile plastic gloves and placed into 50 mL conical-bottom tubes. Freshly voided faecal samples from canines and equines were collected immediately after defecation from the ground. Faecal samples were excluded from the study if they were collected from the ground and could not be associated with a specific host species. Each faecal sample was given a distinct identification code.

Microscopic examination

Direct wet mount microscopy was the first method used to detect Giardia cysts in faecal samples. All collected samples were then shipped to the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (Tehran) for downstream molecular testing. Faecal samples were stored at 4 °C without preservatives until molecular analysis, for a maximum period of 20 weeks.

DNA extraction and purification

Total DNA was extracted from an aliquot of approximately 250 mg from each faecal sample using the Stool DNA Extraction Kit (Yekta Tajhiz Azma, Tehran, Iran) following the manufacturer’s instructions91. The extracted and purified DNA samples were then stored at -20 °C until molecular analysis.

Molecular detection

To identify Blastocystis sp., Cryptosporidium spp., G. duodenalis and E. bieneusi, a real-time PCR (qPCR) assay was employed to amplify gene fragments of different sizes using specific primers selected for these parasites, as detailed in Table 592,93,94,95. This qPCR protocol was conducted on a Rotor Gene Q system (QIAGEN, Germany). The assays were carried out in a total reaction volume of 15 μL, consisting of 7.5 μL of 2X Real-Time PCR Master Mix (BIOFACT, Korea), 0.5 μL of each forward and reverse primer (5 ρmol/μL), 3 μL of template DNA, and 3.5 μL of double distilled water. The cycling profile involved an initial activation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 25 s, annealing at 59 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 20 s. Additionally, there was a temperature ramp from 70 °C to 95 °C at a rate of 1 °C per second. Positive and negative controls were included to ensure the validity of the results, and the assays were performed in duplicate to enhance reliability. Post-amplification melting-curve analyses were performed to detect any primer-dimer artifacts and to confirm reaction specificity. Results were regarded as negative if the cycle threshold (Ct) value was greater than 38 or if no amplification curve was observed.

Genetic characterization

Samples with Ct values of 35 or lower were re-evaluated through sequence-based genotyping analyses utilizing specific markers to assess the molecular diversity of Blastocystis sp., E. bieneusi, and G. duodenalis. A direct PCR protocol targeting a 600-bp partial sequence of the ssu rRNA gene of Blastocystis sp. was conducted as described by Scicluna et al.96. A 410-bp fragment of the ITS gene of E. bieneusi was amplified using a previously described nested PCR protocol97. A nested-PCR protocol was employed to amplify the glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) gene of G. duodenalis, resulting in a final PCR product of 530 bp98.

Sequence analyses

The PCR products of the expected size were directly sequenced in both directions using the internal primer sets described above on an ABI 3130 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). The results of the sequencing were refined and trimmed using BioEdit software version 7.2.6.1. The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/) was employed to compare the generated nucleotide consensus sequences with reference sequences available in GenBank. All sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database under the following accession numbers: PQ137008 to PQ137034 (E. bieneusi), PQ211066 (Blastocystis sp.) and PQ139658 (G. duodenalis).

Phylogenetic analyses

Nucleotide sequences generated in this study, along with relevant reference sequences retrieved from GenBank, were used to construct phylogenetic trees. The neighbor-joining method was employed to assess the phylogenetic relationships among genotypes and subtypes, with genetic distances calculated with the Jukes-Cantor model. Branch reliability was evaluated through bootstrapping with 1,000 replicates. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using MEGA XI software99.

Statistical analysis

Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) was used to evaluate the agreement between microscopy and qPCR in detecting Giardia infection, with interpretations ranging from no agreement (κ ≤ 0) to almost perfect agreement (0.81 < κ ≤ 1). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Data availability

All sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/) under the following accession numbers: PQ137008 to PQ137034 (E. bieneusi), PQ211066 (Blastocystis sp.) and PQ139658 (G. duodenalis).

References

Clark, C. G., van der Giezen, M., Alfellani, M. A. & Stensvold, C. R. Recent developments in Blastocystis research. Adv. Parasitol. 82, 1–32 (2013).

Li, W., Feng, Y. & Santin, M. Host specificity of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and public health implications. Trends Parasitol. 35, 436–451 (2019).

Ryan, U. M., Feng, Y., Fayer, R. & Xiao, L. Taxonomy and molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium and Giardia—A 50 year perspective (1971–2021). Int. J. Parasitol. 51, 1099–1119 (2021).

Hatam-Nahavandi, K. et al. Occurrence and assemblage distribution of Giardia duodenalis in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in southeastern Iran (2019–2022). Gut Pathog. 16, 68 (2024).

Hublin, J. S. Y., Maloney, J. G. & Santin, M. Blastocystis in domesticated and wild mammals and birds. Res. Vet. Sci. 135, 260–282 (2021).

Didarlu, H. et al. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium and microsporidial infection in HIV-infected individuals. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 118, 293–298 (2024).

Smith, H. V., Caccio, S. M., Cook, N., Nichols, R. A. & Tait, A. Cryptosporidium and Giardia as foodborne zoonoses. Vet. Parasitol. 149, 29–40 (2007).

Ma, J. Y. et al. Waterborne protozoan outbreaks: an update on the global, regional, and national prevalence from 2017 to 2020 and sources of contamination. Sci. Total. Environ. 806, 150562 (2022).

Geurden, T. et al. The effect of a fenbendazole treatment on cyst excretion and weight gain in calves experimentally infected with Giardia duodenalis. Vet. Parasitol. 169, 18–23 (2010).

Bourli, P., Vafae-Eslahi, A., Tzoraki, O. & Karanis, P. Waterborne transmission of protozoan parasites: a review of worldwide outbreaks—an update 2017–2022. J. Water Health 21, 1421–1447 (2023).

Budu-Amoako, E., Greenwood, S. J., Dixon, B. R., Barkema, H. W. & McClure, J. Foodborne illness associated with Cryptosporidium and Giardia from livestock. J. Food. Prot. 74, 1944–1955 (2011).

Stensvold, C. R. & Clark, C. G. Pre-empting Pandora’s box: Blastocystis subtypes revisited. Trends Parasitol. 36, 229–232 (2020).

Cacciò, S. M., Lalle, M. & Svärd, S. G. Host specificity in the Giardia duodenalis species complex. Infect. Genet. Evol. 66, 335–345 (2018).

Ryan, U. & Zahedi, A. Molecular epidemiology of giardiasis from a veterinary perspective. Adv. Parasitol. 106, 209–254 (2019).

Feng, Y., Ryan, U. M. & Xiao, L. Genetic diversity and population structure of Cryptosporidium. Trends Parasitol. 34, 997–1011 (2018).

Ježková, J. et al. Cryptosporidium myocastoris n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae), the species adapted to the Nutria (Myocastor coypus). Microorganisms 9, 813 (2021).

Zahedi, A., Bolland, S. J., Oskam, C. L. & Ryan, U. Cryptosporidium abrahamseni n. sp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiiae) from red-eye tetra (Moenkhausia sanctaefilomenae). Exp. Parasitol. 223, 108089 (2021).

Ryan, U., Fayer, R. & Xiao, L. Cryptosporidium species in humans and animals: current understanding and research needs. Parasitoloy 141, 1667–1685 (2014).

Fallah, E., Mahdavi Poor, B., Jamali, R., Hatam-Nahavandi, K. & Asgharzadeh, M. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium Isolates from cattle in a slaughterhouse in Tabriz, northwestern Iran. J. Biol. Sci. 8, 639–643 (2008).

Hatam-Nahavandi, K. et al. Microscopic and molecular detection of Cryptosporidium andersoni and Cryptosporidium xiaoi in wastewater samples of Tehran Province, Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 11, 499–506 (2016).

Razakandrainibe, R. et al. Common occurrence of Cryptosporidium hominis in asymptomatic and symptomatic calves in France. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, e0006355 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Koehler, A. V., Wang, T. & Gasser, R. B. Enterocytozoon bieneusi of animals-With an “Australian twist”. Adv. Parasitol. 111, 1–73 (2021).

Maloney, J. G., da Cunha, M. J. R., Molokin, A., Cury, M. C. & Santin, M. Next-generation sequencing reveals wide genetic diversity of Blastocystis subtypes in chickens including potentially zoonotic subtypes. Parasitol. Res. 120, 2219–2231 (2021).

Hernández-Castro, C. et al. Identification and validation of novel Blastocystis subtype ST41 in a Colombian patient undergoing colorectal cancer screening. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 70, e12978 (2023).

Yu, M. et al. Extensive prevalence and significant genetic differentiation of Blastocystis in high- and low-altitude populations of wild rhesus macaques in China. Parasit. Vectors 16, 107 (2023).

Santin, M. et al. Division of Blastocystis ST10 into three new subtypes: ST42-ST44. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 71, e12998 (2024).

Shams, M. et al. Current global status, subtype distribution and zoonotic significance of Blastocystis in dogs and cats: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasit. Vectors 15, 225 (2022).

Deng, L. et al. Experimental colonization with Blastocystis ST4 is associated with protective immune responses and modulation of gut microbiome in a DSS-induced colitis mouse model. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79, 245 (2022).

Deng, L. et al. Colonization with ubiquitous protist Blastocystis ST1 ameliorates DSS-induced colitis and promotes beneficial microbiota and immune outcomes. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 22 (2023).

Jafari, H., Razi Jalali, M. H., Seyfi Abad Shapouri, M. & Haji Hajikolaii, M. R. Determination of Giardia duodenalis genotypes in sheep and goat from Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 38, 81–84 (2014).

Kiani-Salmi, N. et al. Akrami-Mohajeri, Molecular typing of Giardia duodenalis in cattle, sheep and goats in an arid area of central Iran. Infect. Genet. Evol. 75, 104021 (2019).

Jafari, H., Razi Jalali, M. H., Seyfi Abad Shapouri, M. & Haji Hajikolaii, M. R. Prevalence and genotyping of Giardia duodenalis among Arabian horses in Ahvaz, southwest of Iran. Arch. Razi. Inst. 71, 177–181 (2016).

Homayouni, M. M., Razavi, S. M., Shaddel, M. & Asadpour, M. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia intestinalis in household dogs and cats from Shiraz, Southwestern Iran. Vet. Ital. 55, 311–318 (2019).

Esmailzadeh, R., Malekifard, F., Rakhshanpour, A. & Tavassoli, M. Frequency and genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in dogs of Urmia, northwest of Iran. Vet. Res. Forum 14, 335–340 (2023).

Pirestani, M., Sadraei, J., Dalimi Asl, A., Zavvar, M. & Vaeznia, H. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium isolates from human and bovine using 18S rRNA gene in Shahriar county of Tehran, Iran. Parasitol. Res. 103, 447–467 (2008).

Fotouhi Ardakani, R., Fasihi Harandi, M., Solayman Banai, S., Kamyabi, H. & Atapour, M. Epidemiology of Cryptosporidium infection of cattle in Kerman/Iran and molecular genotyping of some isolates. J. Kerman Univ. Med. Sci. 15, 313–320 (2008).

Keshavarz, A., Haghighi, A., Athari, A., Kazemi, B. & Abadi, A. Prevalence and molecular characterization of bovine Cryptosporidium in Qazvin province, Iran. Vet. Parasitol. 160, 316–318 (2009).

Asadpour, M., Razmi, G., Mohhammadi, G. & Naghibi, A. Prevalence and molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. in pre-weaned dairy calves in Mashhad area, khorasan razavi province, Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 8, 601–607 (2013).

Mirzai, Y., Yakhchali, M. & Mardani, K. Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium andersoni infection in naturally infected cattle of northwest Iran. Vet. Res. Forum 5, 55–60 (2014).

Mahami Oskouei, M. et al. Molecular and parasitological study of Cryptosporidium isolates from cattle in Ilam, west of Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 9, 435–440 (2014).

Firoozi, Z. et al. Prevalence and genotyping identification of Cryptosporidium in adult ruminants in central Iran. Parasit. Vectors 12, 510 (2019).

Badparva, E., Sadraee, J. & Kheirandish, F. Genetic diversity of Blastocystis isolated from cattle in Khorramabad, Iran. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 8, e14810 (2015).

Sharifi, Y., Abbasi, F., Shahabi, S., Zaraei, A. & Mikaeili, F. Comparative genotyping of Blastocystis infecting cattle and human in the south of Iran. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 72, 101529 (2020).

Mohammad Rahimi, H., Mirjalali, H. & Zali, M. R. Molecular epidemiology and genotype/subtype distribution of Blastocystis sp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Encephalitozoon spp. in livestock: concern for emerging zoonotic infections. Sci. Rep. 11, 17467 (2021).

Rostami, M. et al. Genetic diversity analysis of Blastocystis subtypes and their distribution among the domestic animals and pigeons in northwest of Iran. Infect. Genet. Evol. 86, 104591 (2020).

Salehi, R., Rostami, A., Mirjalali, H., Stensvold, C. R. & Haghighi, A. Genetic characterization of Blastocystis from poultry, livestock animals and humans in the southwest region of Iran—zoonotic implications. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 69, 1178–1185 (2022).

Shams, M. et al. First molecular characterization of Blastocystis subtypes from domestic animals (sheep and cattle) and their animal-keepers in Ilam, western Iran: a zoonotic concern. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 71, e13019 (2024).

Asghari, A. et al. First molecular subtyping and zoonotic significance of Blastocystis sp. in dromedary (C. dromedarius) and Bactrian (C. bactrianus) camels in Iran: a molecular epidemiology and review of available literature. Vet. Med. Sci. 10, e1442 (2024).

Mohammadpour, I. et al. First molecular subtyping and phylogeny of Blastocystis sp. isolated from domestic and synanthropic animals (dogs, cats and brown rats) in southern Iran. Parasit. Vectors 13, 365 (2020).

Kord-Sarkachi, E., Tavalla, M. & Beiromvand, M. Molecular diagnosis of microsporidia strains in slaughtered cows of southwest of Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 42, 81–86 (2018).

Shafiee, A., Shokoohi, G., Saadatnia, A. & Abolghazi, A. Molecular detection of microsporidia in cattle in Jahrom, Iran. Avicenna. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10, 126–130 (2023).

Delrobaei, M. et al. Molecular detection and genotyping of intestinal microsporidia from stray dogs in Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 14, 159–166 (2019).

Cleaveland, S., Laurenson, M. K. & Taylor, L. H. Diseases of humans and their domestic mammals: Pathogen characteristics, host range and the risk of emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356, 991–999 (2001).

Hatam-Nahavandi, K. et al. Gastrointestinal parasites of domestic mammalian hosts in southeastern Iran. Vet. Sci. 10, 261 (2023).

Bouzid, M., Halai, K., Jeffreys, D. & Hunter, P. R. The prevalence of Giardia infection in dogs and cats, a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies from stool samples. Vet. Parasitol. 207, 181–202 (2015).

Schuurman, T., Lankamp, P., van Belkum, A., Kooistra-Smid, M. & van Zwet, A. Comparison of microscopy, real-time PCR and a rapid immunoassay for the detection of Giardia lamblia in human stool specimens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13, 1186–1191 (2007).

Elsafi, S. H. et al. Comparison of microscopy, rapid immunoassay, and molecular techniques for the detection of Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitol. Res. 112, 1641–1646 (2013).

Malekifard, F. & Ahmadpour, M. Molecular detection and identification of Giardia duodenalis in cattle of Urmia, northwest of Iran. Vet. Res. Forum 9, 81–85 (2018).

Minetti, C. et al. Occurrence and diversity of Giardia duodenalis assemblages in livestock in the UK. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 61, e60–e67 (2014).

Cardona, G. A. et al. Unexpected finding of feline-specific Giardia duodenalis assemblage F and Cryptosporidium felis in asymptomatic adult cattle in Northern Spain. Vet. Parasitol. 209, 258–263 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Statewide cross-sectional survey of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in California cow-calf herds. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 72, 461–466 (2019).

Bartley, P. M. et al. Detection of potentially human infectious assemblages of Giardia duodenalis in fecal samples from beef and dairy cattle in Scotland. Parasitology 146, 1123–1130 (2018).

Santin, M. & Fayer, R. A longitudinal study of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in dairy cattle. Parasitol. Res. 105, 141–144 (2009).

Juránková, J., Kamler, M., Kovařčík, K. & Koudela, B. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV) infected and noninfected cattle herds. Res. Vet. Sci. 94, 100–104 (2013).

Stensvold, C. R., Beser, J., Ljungström, B., Troell, K. & Lebbad, M. Low host-specific Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype BEB6 is common in Swedish lambs. Vet. Parasitol. 205, 371–374 (2014).

Ye, J. et al. Dominance of Giardia duodenalis assemblage A and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype BEB6 in sheep in Inner Mongolia, China. Vet. Parasitol. 210, 235–239 (2015).

Valenčáková, A. & Danišová, O. Molecular characterization of new genotypes Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Slovakia. Acta Trop. 191, 217–220 (2019).

Udonsom, R. et al. Identification of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in goats and cattle in Thailand. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 308 (2019).

Wegayehu, T., Li, J., Karim, M. R. & Zhang, L. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in lambs in Oromia special zone, central Ethiopia. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 6 (2020).

Askari, Z. et al. Molecular detection and identification of zoonotic microsporidia spore in fecal samples of some animals with close-contact to human. Iran. J. Parasitol. 10, 381–388 (2015).

Li, W. C., Wang, K. & Gu, Y. F. Detection and genotyping study of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sheep and goats in east-central China. Acta Parasitol. 64, 44–50 (2019).

Zhou, H. H. et al. Genotype identification and phylogenetic analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in farmed black goats (Capra hircus) from China’s Hainan Province. Parasite 26, 62 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in farmed goats and sheep in Ningxia, China. Infect. Genet. Evol. 85, 104559 (2020).

Gómez Puerta, L. A. Caracterizacón molecular de genotipos de Enterocytozoon bieneusi y ensamblajes de Giardia duodenalis aislados de heces de crías de alpaca (Vicugna pacos). MSc thesis, Universidad Nacionl Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru. 120. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12672/4815 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium spp., Giardia duodenalis, and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive wildlife at Zhengzhou Zoo, China. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 62, 833–839 (2015).

Li, W. et al. Multilocus genotypes and broad host-range of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in captive wildlife at zoological gardens in China. Parasit. Vectors 9, 395 (2016).

Baroudi, D. et al. Divergent Cryptosporidium parvum subtype and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in dromedary camels in Algeria. Parasitol. Res. 117, 905–910 (2018).

Koehler, A. V. et al. First cross-sectional, molecular epidemiological survey of Cryptosporidium, Giardia and Enterocytozoon in alpaca (Vicugna pacos) in Australia. Parasit. Vectors 11, 498 (2018).

Zhang, Q. et al. Molecular detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in alpacas (Vicugna pacos) in Xinjiang, China. Parasite 26, 31 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Concurrent infections of Giardia duodenalis, Enterocytozoon bieneusi, and Clostridium difficile in children during a cryptosporidiosis outbreak in a pediatric hospital in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2437 (2013).

Zhang, T. et al. Molecular prevalence and genetic diversity analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in humans in Hainan Province, China: High diversity and unique endemic genetic characteristics. Front. Public Health. 10, 1007130 (2022).

Yildirim, Y. et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi in raw milk of cattle, sheep and water buffalo in Turkey: Genotype distributions and zoonotic concerns. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 334, 108828 (2020).

Santín, M., Dargatz, D. & Fayer, R. Prevalence and genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in weaned beef calves on cow-calf operations in the USA. Parasitol. Res. 110, 2033–2341 (2012).

Zhang, Q. et al. Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotypes in Tibetan sheep and yaks. Parasitol. Res. 117, 721–727 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Identification and genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 2006–2008 (2011).

Shi, K. et al. Molecular survey of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in sheep and goats in China. Parasit Vectors 9, 23 (2016).

Jian, Y. et al. First report on the molecular detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in livestock and wildlife around Qinghai Lake in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau area, China. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 21, 110–115 (2023).

Deng, L. et al. First identification and molecular subtyping of Blastocystis sp. in zoo animals in southwestern China. Parasit Vectors 14, 11 (2021).

Khaled, S. et al. Prevalence and subtype distribution of Blastocystis sp. in Senegalese school children. Microorganisms 8, 1408 (2020).

Jinatham, V., Maxamhud, S., Popluechai, S., Tsaousis, A. D. & Gentekaki, E. Blastocystis one health approach in a rural community of Northern Thailand: Prevalence, subtypes and novel transmission routes. Front. Microbiol. 12, 746340 (2021).

Hatam-Nahavandi, K. et al. Subtype analysis of Giardia duodenalis isolates from municipal and domestic raw wastewaters in Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 12740–12747 (2017).

Verweij, J. J., Ten Hove, R., Brienen, E. A. & van Lieshout, L. Multiplex detection of Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Encephalitozoon spp. in fecal samples using real-time PCR. Diag. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 57, 163–167 (2007).

Jothikumar, N., da Silva, A. J., Moura, I., Qvarnstrom, Y. & Hill, V. R. Detection and differentiation of Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum by dual TaqMan assays. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 1099–1105 (2008).

Mohammad Rahimi, H. et al. Development and evaluation of high-resolution melting curve analysis for rapid detection and subtyping of Blastocystis and comparison the results with sequencing. Parasitol. Res. 118, 3469–3478 (2019).

Bahramdoost, Z., Mirjalali, H., Yavari, P. & Haghighi, A. Development of HRM real-time PCR for assemblage characterization of Giardia lamblia. Acta Trop. 224, 106109 (2021).

Scicluna, S. M., Tawari, B. & Clark, C. G. DNA Barcoding of Blastocystis. Protist 157, 77–85 (2006).

Mirjalali, H. et al. Genotyping and molecular analysis of Enterocytozoon bieneusi isolated from immunocompromised patients in Iran. Infect. Gen. Evol. 36, 244–249 (2015).

Mohammad Rahimi, H., Javanmard, E., Taghipour, A., Haghighi, A. & Mirjalali, H. Multigene typing of Giardia duodenalis isolated from tuberculosis and non-tuberculosis subjects. PLoS ONE 18, e0283515 (2023).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the Foodborne and Waterborne Diseases Research Center for their supports. The current study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, with approval ID: IR.SBMU.RIGLD.REC.1402.011.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant Number: 43007796).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT authorship contribution statement Conceptualization: KHN, MR, HM, EA, MB. Methodology: HM, HMR. Formal analysis: KHN. Writing-original draft preparation: KHN. Writing-review and editing: EA, MB, HM. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hatam-Nahavandi, K., Mohammad Rahimi, H., Rezaeian, M. et al. Detection and molecular characterization of Blastocystis sp., Enterocytozoon bieneusi and Giardia duodenalis in asymptomatic animals in southeastern Iran. Sci Rep 15, 6143 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90608-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90608-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Extracellular vesicles in intestinal protozoa: hidden mediators of host-parasite communication

Gut Pathogens (2025)

-

Genotyping and molecular profiling of intestinal microsporidiosis and cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected patients in Alborz Province, Iran

Gut Pathogens (2025)

-

Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection among patients with beta-thalassemia major: a case-control study in Southeastern Iran

BMC Infectious Diseases (2025)

-

Epidemiological aspects of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southeastern Iran from 2019 to 2023

Journal of Parasitic Diseases (2025)

-

First Data on the Occurrence and Genotyping of Enterocytozoon bieneusi in Wrestling Camels in Türkiye

Acta Parasitologica (2025)