Abstract

Detecting cassava leaf disease is challenging because it is hard to identify diseases accurately through visual inspection. Even trained agricultural experts may struggle to diagnose the disease correctly which leads to potential misjudgements. Traditional methods to diagnose these diseases are time-consuming, prone to error, and require expert knowledge, making automated solutions highly preferred. This paper explores the application of advanced deep learning techniques to detect as well as classify cassava leaf diseases which includes EfficientNet models, DenseNet169, Xception, MobileNetV2, ResNet models, Vgg19, InceptionV3, and InceptionResNetV2. A dataset consisting of around 36,000 labelled images of cassava leaves, afflicted by diseases such as Cassava Brown Streak Disease, Cassava Mosaic Disease, Cassava Green Mottle, Cassava Bacterial Blight, and healthy leaves, was used to train these models. Further the images were pre-processed by converting them into grayscale, reducing noise using Gaussian filter, obtaining the region of interest using Otsu binarization, Distance transformation, as well as Watershed technique followed by employing contour-based feature selection to enhance model performance. Models, after fine-tuned with ADAM optimizer computed that among the tested models, the hybrid model (DenseNet169 + EfficientNetB0) had superior performance with classification accuracy of 89.94% while as EfficientNetB0 had the highest values of precision, recall, and F1score with 0.78 each. The novelty of the hybrid model lies in its ability to combine DenseNet169’s feature reuse capability with EfficientNetB0’s computational efficiency, resulting in improved accuracy and scalability. These results highlight the potential of deep learning for accurate and scalable cassava leaf disease diagnosis, laying the foundation for automated plant disease monitoring systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz), commonly known as manioc or yucca, is a vital crop from the spurge family, predominantly cultivated in Africa. Originally native to South America, it is now extensively grown in tropical and subtropical regions, providing affordable nutrition to over 500 million people globally. It is the third-largest source of carbohydrates, provided through its edible tubers, while its green leaves are consumed in some regions like Africa as a source of proteins, vitamin A, and vitamin B1. Cassava thrives in poor soil conditions, with harvest periods ranging from 6 months to 3 years after planting. Besides its role in food security, cassava contributes significantly to economic growth and serves as a low-cost starch source for various industries2. In 2021, global cassava production totalled 324.7 million tonnes, with Africa accounting for 64.7%, followed by Asia (26.7%), America (8.5%), and Oceania (0.1%)3. By 2023, the global cassava processing market had reached 319.9 million tonnes and is projected to grow to 369.7 million tonnes by 2032. However, as of 2024, production has declined in some regions, such as Thailand and Sub-Saharan Africa, primarily due to disease outbreaks, including Cassava Brown Streak Disease (CBSD), Cassava Bacterial Blight (CBB), Cassava Mosaic Disease (CMD), and Cassava Green Mottle (CGM)4,5.

Traditional methods for identifying plant diseases often rely on experts who visit fields, inspect plants manually, and provide assessments. However, these methods have several drawbacks, especially in developing regions where there may not be enough trained professionals or proper infrastructure, making the process slow, expensive, and inefficient6. As a result, detecting cassava diseases in time becomes difficult, leading to lower crop yields and financial losses for farmers. To solve this problem, modern approaches using AI technologies like machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are becoming more popular7. These AI techniques can make disease detection faster, more accurate, and easier to scale. Deep learning models trained on plant images are very effective in identifying diseases and can help overcome issues related to limited resources and infrastructure8,9. In addition to this, combining these models has emerged as a promising approach to leverage the unique strengths of individual architectures. For example, hybrid models can integrate the feature reuse capabilities of the models in achieving superior performance compared to standalone models. Such combinations enhance the ability to capture intricate patterns while maintaining scalability and efficiency, making them highly effective for agricultural applications10.

Existing research methods used to detect cassava plant diseases have several drawbacks which partly explain why there is a need for better approaches. Several methods suffer from high variance and poor transfer of performance over different field environments while as few suffer from several inadequacies such as unbalanced or restricted data results that limit model performance in real-life settings. Other challenges include early and mild signs of the disease; presence of noises or other signals in the background; and lack of proper feature extraction. These limitations call for improved strategies which can boost the efficiency, capacity and steadiness in cassava disease control.

Keeping the above facts in consideration, the aim of the paper is to design an automated system that can accurately detect diseases in cassava plants and classify them into respective categories. The following are the contributions made by this paper:

-

Comprehensive analysis of existing work related to cassava plant disease detection and classification.

-

Preprocessing of around 36,000 images using grayscale conversion and noise removal techniques to enhance image quality.

-

Segmentation of images using Otsu thresholding, distance transformation, and the watershed technique for precise depiction of regions of interest.

-

Contour feature extraction based on image characteristics such as area, perimeter, and other shape descriptors.

-

Application of multiple deep transfer learning techniques for disease classification in cassava plants, with performance evaluation based on multiple measures like accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, loss, learning curves, and confusion matrix.

-

This research provides a foundation for future studies, helping researchers improve the detection and classification of plant diseases through enhanced deep learning methodologies.

Literature work

Many researchers have put forward multiple algorithms of machine learning and deep learning to address the issue of detecting diseases in Cassava leaves accurately. Hence in this part, we have taken few recent papers to understand what techniques researchers have used and what results they have obtained along with the limitations which will be addressed in this research work.

Methodologies employed for disease detection

Several studies have leveraged advanced machine learning and deep learning methods for cassava disease detection, focusing on both pre-trained architectures and custom innovations. Pre-trained CNN models have been widely adopted, such as Alford and Tuba’s (2024)11 application of VGG19 through transfer learning, achieving a test accuracy of 80.27% but showing overfitting to training data. Similarly, Singh et al. (2023)12 employed InceptionResNetV2, reporting an accuracy of 87%, though the model’s potential was constrained by insufficient training epochs. In terms of custom architectures, Tewari and Kumari (2024)5 developed a lightweight model incorporating channel attention mechanisms, which delivered strong validation results but struggled to generalize in real-world scenarios, achieving 75% test accuracy. Zhang et al. (2024)13 introduced MAIANet, utilizing multi-attention methods to reach an impressive accuracy of 95.83%; however, its high computational cost made it impractical for deployment in low-resource environments. Ravi et al. (2021)14 employed attention-based EfficientNet variants and achieved high accuracy on balanced datasets but faced scalability issues in real-world settings due to limited dataset diversity. Additionally, Sholihin et al. (2023)15 used AlexNet as a feature extractor combined with an SVM classifier, achieving 90.7% accuracy but noted challenges due to the small dataset size, which hindered scalability. Haq et al. (2023)16 addressed the critical challenge of early pest detection in agriculture using CNN-based models. They employed the Cov2D library and VGG-16 to identify pest attacks on maize plants. A personal dataset of 7000 pest-attacked leaf images, categorized into two classes, was used for model training and evaluation. Likewise, these researchers17 also presented a real-time weed detection system in wheat crops using deep learning models implemented with TensorFlow and PyTorch. A total of 6000 images were collected from the PMAS Arid Agriculture University research farm under varying weather conditions. Their best-performing model achieved weed detection accuracies of 0.89 and 0.91 with inference times of 9.43 ms and 12.38 ms, respectively, on an NVIDIA RTX2070 GPU for 640 × 640 resolution images.

Key findings and performance trends

Overfitting and generalization problems were often highlighted, accentuating the need for models that generalize well on unseen data. Most especially, the lightweight model of Tewari and Kumari (2024)5 suffers alarming performance drops during testing that it exposes the generalization of lightweight architectures. In contrast, Prashanth et al. (2024)18 came up with impressive accuracy (99.02%) with their newly introduced model, MPCSAR-AHH, but the advanced hardware requirement limits its usability within low-resource environments. Likewise, such Enhanced Convolutional Neural Networks (ECNN) were introduced by Lilhore et al. (2022)19 using depth-wise separable convolutions and gamma correction, with an impressive result of 99.3% accuracy on a balanced dataset, but faced scalability and real-world deployment issues. Quality and diversity of datasets are critical factors in model life performance; many studies have shown high accuracy with well-curated datasets but have difficulty validating the results with diverse real-world data. For example, Ravi et al. (2021)14 and Sapre et al. (2023)20 state that models trained on imbalanced datasets or simpler architectures like ANN tend to lose their generalization ability and exhibit poor performance. Lanjewar & Parab (2024)21 illustrated deep learning (CNN and transfer learning) to detect diseases in citrus leaves using models like ResNet152V2, InceptionResNetV2, DenseNet121, and DenseNet201 for classification. The models achieved augmented data with high performance of 98% accuracy, F1 score 99%, and ROC-AUC 0.99.

Emerging trends and practical implications

Hybrid and ensemble approaches have gained traction in leveraging complementary strengths of multiple architectures. For example, Ravi et al.‘s (2021)14 ensemble meta-classifier demonstrated effectiveness in improving classification performance by combining predictions from multiple models. However, these methods often encounter challenges in computational efficiency, making them less suitable for real-time applications.

Conversely, there is a growing focus on lightweight and scalable solutions. Models like MobileNetV2 and Tewari and Kumari’s lightweight architecture are favoured for low-resource environments due to their emphasis on mobility and edge deployment. Despite their advantages in efficiency, these models sometimes compromise on accuracy, as reflected in studies reporting suboptimal F1 scores and performance drops during testing. Additionally, Prashanth et al. (2024)18 and Zhang et al. (2024)13 highlighted the trade-off between accuracy and computational demands, particularly when employing advanced attention mechanisms. Panchbai et al. (2024)22 developed a system to predict diseases in cashew nuts and fruits to help ensure food security, particularly during times of rapid population growth. A new model, CAS-CNN, was developed, along with a modified version of MobileNetV2 (CAS-MODMOBNET) and achieved an impressive 99.8% accuracy and an AUC of 1.0 on the Test subset. Additionally, the researchers analyzed the model’s size, number of layers, and parameters against those of existing TL models. Lanjewar et al. (2024)23 focused on detecting healthy and diseased citrus leaves using deep learning models. Four pre-trained deep CNN models—ResNet152V2, InceptionResNetV2, DenseNet121, and DenseNet201—were used for classification out of which the modified DenseNet achieved high performance with 98% accuracy, 99% F1 score, and an AUC of 0.99.

Gaps addressed by current research

Most of the existing models demonstrated overfitting with a high training accuracy coupled with lower test or validation accuracy, which is extremely problematic when it comes to generalization for the real world. In addition, the limitation due to computational demands was another point where advanced architectures using attention across the models or ensemble approaches require heavy resources that limit scalability and feasibility of deployment. A vital issue was dataset imbalance; for example, many classes remained underrepresented amongst diseased classes resulting in biased models and skewed results across categories. Also, environmental variability, such as variety in image quality and lighting conditions, in addition to background noise, adds to disease detection complexity and underscores the demand for robust and adaptable solutions in real-world agricultural settings.

Research methodology

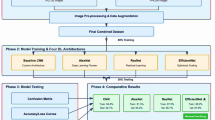

This section covers the description of various phases that are used for the development of an automated cassava leaf disease detection and classification using multiple image processing, segmentation, feature extraction, and deep learning techniques, as shown in Fig. 1.

Dataset

The Cassava Leaf Disease Dataset is a collection of images designed for identifying and classifying various diseases affecting cassava plant leaves such as Cassava Bacterial Blight, Healthy, Cassava Green Mottle, Cassava Mosaic Disease, and Cassava Brown Streak Disease, as shown in Fig. 2. The dataset is divided into training and test images, where the training images are labelled and used to train machine learning models, and the test images are used to evaluate model performance. The dataset contains 21,397 training images and 15,000 testing images. Besides the dataset al.so has two “.csv” files i.e. train.csv which has name of images as well as their corresponding unique id codes of diseases and sample_Submission.csv which has images files with predicted labels. Moreover, the dataset has also the images in TFRecord format for mapping the labelID of each disease to its actual name. Figure 3 illustrates the number of images per class24.

Preprocessing

Preprocessing of images is a very crucial step in the image detection and classification task. In this research, we have initially converted the RGB image into grayscale to reduce the complexity and the computational load. In this process, all the three-color channels of the original image of cassava leaf are converted into single channel. Further, the pixel of the image is being assigned a grayscale value based on their combination of RGB values (Fig. 4). Equation (1) is used to convert RGB into grayscale values.

After converting into grayscale, another important factor is to remove or reduce the noise as it can impact the classification of cassava plant disease. Here we have used Gaussian filter which works on the average of the pixel values of an image calculated using Gaussian distribution. Gaussian filter has been used because of its ability to smoothen the image and reduce high frequency noise (Fig. 5). This filter is applied by computing convolution operation between image and Gaussian function which is being represented by bell shaped curve. Generally, this technique works on the principle that those pixels which are closer to the target pixel has more contribution to the weighted average while as those which are far have less contribution25. Mathematically, it is calculated by eq(ii).

Here, x and y are co-ordinates, \(\:\sigma\:\) is the standard deviation.

Segmentation

For segmentation, three techniques have been used i.e. Otsu thresholding, Distance transformation, and watershed segmentation. In case of Otsu binarization, the grayscale is converted into binary image in which the pixel values are either in the form of 0 or 1 (black and white respectively). Here optimal threshold value is being determined either on the basis of two-pixel values i.e. foreground(object) and background or minimizing the intra class variance. From all the possible threshold values, this technique selects the value which separates the intensities of pixel into two groups26. Further, the technique computed the distance between the two groups by maximizing the inter class variance and provides a clear difference between object and background (Fig. 6). Equation (3) is used to compute the Otsu binarization technique.

Within-Class Variance

Here

Between-Class Variance

Here

Optimal threshold

\(\:p\left(i\right)=\:\)probability of pixel intensity i, \(\:{\omega\:}_{1}\left(t\right),\:{\omega\:}_{2}\left(t\right)\) = cumulative weight of background and foreground class, \(\:{\mu\:}_{1}\left(t\right),\:{\mu\:}_{2}\left(t\right)\) = mean intensity of background and foreground class respectively.

The second technique used is distance transform which is used for computing the distance of each pixel in a binary image to the nearest foreground or background pixel. In this research work, the Euclidean Distance Transform (EDT) has been used to generate a new image where each pixel’s value reflects its distance from the nearest foreground pixel. In a binary image, foreground pixels represent the objects of interest, while background pixels are those that do not contain these objects. EDT calculates the Euclidean distance for each background pixel to the closest foreground pixel, resulting in a distance map. In this map, the values assigned to each pixel are proportional to their distance from the nearest foreground pixel, effectively creating a smooth gradient that highlights the proximity to the objects (Fig. 7). This transformation aids in various image processing tasks, such as segmentation and feature extraction, by providing a clear spatial relationship between foreground and background regions27.

Here D(x, y) = Eulidean distance, F = set of coordinates.

At the end comes the watershed segmentation which segments or separates the objects of an image within the boundary. In watershed segmentation, markers are placed at local minima (valleys) of the intensity values, and the algorithm then simulates the flooding of the valleys, where water fills from the lowest points upward. As the flooding progresses, the water from different valleys starts to meet. To prevent the merging of water from different regions, dams are built at the meeting points, and these dams form the boundaries of the segmented regions. This technique is particularly useful in images where different regions have well-defined boundaries, but it can be sensitive to noise and over-segmentation if the image has many local minima. Preprocessing steps such as smoothing or using markers (manual or automatic) can help improve the effectiveness of watershed segmentation (Fig. 8)28.

Here k = kth marker associated with D(x, y).

Contour feature extraction

In the domain of detecting cassava plant disease, contour feature extraction plays a crucial role to analyse and classify various diseases based on shape characteristics of the leaves. Table 1 includes the parameters whose values are derived from contour analysis of cassava leaf images, and they provide information of different features linked with different diseases and healthy leaves.

Area defines the size of the contour region. In Table 1, Cassava Green Mottle (CGM) indicates a larger contour region with the area of 0.5 as compared to other conditions where the area is zero, such as in Cassava Bacterial Blight (CBB) and Cassava Mosaic Disease (CMD). Perimeter is used for measuring the boundary length of the contour like Cassava Brown Streak Disease (CBSD) has the highest perimeter value of 4.0 and it suggests a more complex contour boundary compared to the healthier leaves, which have a perimeter of 2.0. Further, approximation error in contour detection is defined by epsilon. Here, CBSD reflects more irregularities because of having the highest epsilon value of 0.4 compared to other diseases and healthy leaves. The Width and Height are for describing dimensions of the bounding box around the contour. In the table the largest value has been described in case of CBSD with a width of 3 and a height of 1. The Aspect Ratio provides information on the shape of the contour by calculating width by height. CBSD, with an aspect ratio of 3.0, suggests a more elongated shape compared to other conditions with aspect ratios closer to 1.0 which indicates a more uniform shape. Extent is used for measuring the ratio of the contour area to the bounding box area such as CGM has an extent of 0.125 and it indicates a smaller proportion of the bounding box area covered by the contour. Equivalent Diameter quantifies the diameter of a circle with the same area as the contour. CGM has a significant equivalent diameter of 0.797 which suggests a more substantial contour area compared to other diseases and healthy leaves. The Min Value and Max Value parameters refer to the minimum and maximum pixel intensities within the contour, while Min Value Location and Max Value Location denote their positions. For example, the min and max values for healthy leaves are 131.0 and 135.0, respectively, with their locations indicating where these values are found within the contour. The Mean Color represents the average color intensity within the contour region. For instance, CGM has a mean color value of 149.6 that reflects a different average color compared to other diseases and healthy leaves. Finally, Extreme Points (Leftmost, Rightmost, Topmost, Bottommost) provide the coordinates of the contour’s outer boundaries, which are essential for understanding the contour’s spatial orientation. For example, the extreme points for Cassava Mosaic Disease (CMD) are consistently at (480,599), indicating a specific positioning of the contour within the image.

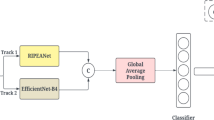

Applied models

This section covers the architectural description (Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18) of the models that have been used for the classification of multiple Cassava leaf diseases.

EfficientNetB0 is the first model of EfficientNet family which starts with stem convolution layer. Stem convolution layer is the first feature extractor; it extracts basic features and textural elements from the input cassava Images. This is succeeded by multiple MBConv blocks that employ depthwise separable conlutions. These convolutions split the standard convolution one into depthwise convolution, which separately filters the input channel to read, and pointwise convolution which consolidates the output of the depthwise convolution. This kind of separation greatly decreases the amount of parameters and computational load with the features maps, yet the feature extraction ability remains highly efficient. The MBConv blocks in EfficientNetB0 are more precisely able to detect optimal features from the cassava images such as the fine details in the images of cassava leaves that are very useful to identify different types of cassava diseases. Finally to aggregate all the features obtained from the extraction process, EfficientNetB0 incorporates Global Average Pooling. This layer down samples the given feature maps from previous convolutional layers in an average manner and retains only the most important features. The consequence of this method is a less detailed vector yet it focuses on important features needed for disease differentiation. The final output is then forwarded to a dense classification layer where the presence as well as the type of disease will be identified29.

Moving to the next is DenseNet169 which ensures that every layer receives information from all the previous layers and transfers information to all the subsequent layers thus creating a dense connection of the layers resulting in efficient information flow and gradients. A structure addresses the problems of deep neural networks, including gradient vanishing and redundancy of features to enhance feature reuse as well as gradient backpropagation. Dense Blocks are central in the performance of DenseNet169. In these blocks, each layer connects all the previous layer’s feature maps to construct complex features incrementally, which are beneficial for the network. This dense connection pattern helps the model in achieving better results of identifying more complex patterns in the cassava leaf images which is very important for identifying the early signs of the disease30. Architecturally, DenseNet169 can incorporate from all smaller features of previous layers to a large set of information to aid in classification leading to enhanced performance in identification of different diseases affecting leaves. The Transition Layers used in the network are placed in-between the dense blocks to control the network’s computational demands. These layers of operation undertake dimensionality reduction with the use of the convolutional layers accompanied by the average pooling operation. This reduction step assists in reducing the computational load and the memory usage while it retains certain salient features for disease categorization. Transition layers maintain a balance between retention of certain features and control of the model’s complexity and computational requirements for implementing the DenseNet169 on large-scale images datasets31.

Then we used the Inception extended model – Xception which integrates depthwise separable convolutions which improves both, efficiency and accuracy. This approach refines the traditional convolutional operations by breaking them into two distinct processes: the depthwise convolutions and the pointwise convolutions. As it has been explained, Depthwise Separable Convolutions are the key constituent of the Xception architecture. As different from the standard convolutions, which convolve each input channel with the same filter, depthwise separable convolutions adhere to a depthwise convolution, where all the input channels are processed separately. This is succeeded by a pointwise convolution through which the results of the depthwise step are combined32. Such separation not only decreases the computational load and the quantity of parameters but also enhances the model’s capacity to abstract intricate patterns and other characteristics. For cassava leaf disease detection, this capability allows Xception to detect fine disease patterns and cues that may hint at other diseases in the cassava leaves. Inception Modules are another important ingredient of Xception deep learning model. These modules involves parallel convolution operations with various kernel sizes to enable the network to sample a range of features and textures at the same time. In reference to images related to cassava leaves, it enhances the model’s ability to interpret other attributes of the leaves in a single image such as different symptoms of a disease or changes in texture. Through the combination of the different feature extractions, the redundancies therein are reduced and Xception provides a more effective diagnosis of disease on the leaves33.

Likewise, we also applied MobileNet V2 which has its focus set towards mobility and edge compute platforms, all the while offering high accuracy in a resource sparing manner. This architecture proposes the depthwise separable convolutions, as well as linear bottleneck layers, to accomplish this objective, yet remains effective for other processes, for example, disease recognition in cassava leaves. Architecture wise, Depthwise Separable Convolutions are at the core of MobileNet V2. These convolutions split the convolution operation into two stages: Standard convolution commonly used in deep learning architecture including depthwise convolutions and pointwise convolutions. The depthwise convolution uses a single filter per input channel and the pointwise convolution uses 1 × 1 convolution to fuse these outputs. This separation drastically reduces the amount of calculations and the number of parameters to be learned compared to regular convolutions making the model a perfect fit for applications in real-time on low-powered devices. In terms of cassava leaf disease detection, this efficiency enables mobile net v2 to process faster through high-resolution images while using low-density matrices to capture features disease. There are also Linear Bottlenecks other than inverted residual branches in MobileNet V2. They are intended to retain key characteristic and avoid information loss during dimensionality reduction. The linear bottleneck concept is something similar to implementations of depthwise separable convolution followed by linear layer where essential feature detail is preserved; however, dimensionality of feature maps is reduced. This is especially useful, especially when trying to recognize the disease symptoms on the cassava leaves, as it preserves the correspondence between the features, which are important for distinguishing between healthy and diseased state34.

In addition to this, two variants of ResNet have been also used. The first one is ResNet50 currently uses residual connections to make it easier to train very deep networks. The Residual Blocks are essentially the building block of the ResNet50 V2 architecture. Every residual block is made up of a several convolutional layers and a shortcut connection which skips one or some layers35. The major difference in this case is that learning is performed not the desired output, but the residual between it and the input. It also makes the gradients to flow through the network in the backpropagation process much easier especially in very deep networks thus preventing the vanishing gradient problem. In the case of cassava leaf disease detection, the residual blocks in ResNet50 V2 help the model learn the hierarchical and more abstract features from the input images to improve the model’s learning capacity and to identify more visible and obscure tapestry of disease patterns and symptoms. Skip Connections also enhance the model’s performance by giving extra routes for the training gradient to progress through. These connections basically establish a way of connecting the output of a layer to another, deeper layer in the network which serve to retain high level of features and enables training of deeper representations. When it comes to diseases in leaves, it helps in defeating the contextual variation in the cassava leaf texture and structure that the skip connection tries to capture to tell the difference between healthy and adulterated leaves36.

Similarly, ResNet152 V2 extends the depth to 152 layers and Deeper Residual Blocks are the characteristic of ResNet152 V2. By extending the network depth, this architecture provides a greater capacity for feature extraction. Every residual block inside the network is trained to learn residual mappings and as such, the depth of the network increases, the model can learn complex patterns and features in cassava leaf images. It is important because the deeper networks, as it has been pointed out earlier, may not easily pick symptoms of diseases compared to the heightened capacity that comes with having a wider network. The deeper residual blocks enhance the learning of the highly implicit relationship in the cassava leaves data for the identification as well as differentiation of a variety of diseases. In the presented work, to improve the performance of the model, Enhanced Skip Connections are used. ResNet152 V2 includes the use of skip connections where input feature maps are connected to the deeper layers of the network in a way that caters for problems normally associated with vanishing gradients thus allowing for efficient training and gradients flow during training. Such connections retain information from previous layers which are very important for feature learning and classification37.

VGG19 architecture can be described as the use of small convoluted kernels combined with pooling layers which allows for fine details of images to be identified and processed. Other features of Convolutional Layers in VGG19 are that the filters used are small and are 3 × 3 in size, stride of 1 and padding of 1 to preserve the spatial dimension of the input in the convolution process. This enables the network to learn a framework of features in stages at different levels of abstraction through stacking of small filters. In the context of identifying cassava leaf diseases, these convolutional layers play an important role of identifying details, texture, and patterns in the provided leaf images. These are important in making a differential diagnosis of early symptoms of the disease and or to tell the difference between a healthy and a diseased leaf. There is no specific name for them, however Max Pooling Layers are usually applied to downsample the feature maps usually by 2 × 2 filter and with a stride of 2. Downsampling layers downsample the feature maps while passing only the important feature to the next successive layers of the network. This feature reduction in a manner also aids to reduce on the computational complexity and focuses only the critical features for the classification. When dealing with cassava leaves the max pooling helps the model to concentrate on the important features that are needed to detect diseases while excluding the less significant details, which in turn enhances the models recognition of different types of diseased leaves38.

Inception V3 uses a variety of convolution operations within its inception modules. It helps the model to extract various features from the input images and is especially useful for difficult image recognition problems like cassava diseases identification. Inception Modules are the basic building blocks of Inception V3. Every Inception module is the result of the parallel performance of several convolution operations with different kernel sizes as well as several pooling operations39. This design means that the network can scan the images for features of different sizes all at once thus will be able to capture the finer as well as the more complex features within the images. In case of cassava leaf disease detection, this capability is very important since the model can understand various forms and colors of the diseases that may appear at various scales and orientations to the cassava leaves. The primary technique called Factorization Techniques are shown to be incorporated and used in optimizing the computational speed of the InceptionV3. This efficiency is especially favorable when it comes to the detection and classification of diseases in the cassava leave because it provides the interact capability to process images of high resolution without compromising much of the computational resources40.

InceptionResNetV2 is one of the more complex approaches of deep learning models that combines the Inception modules with the residual connections. Inception-Residual Blocks form the basis of designing InceptionResNetV2. These blocks incorporate Inception modules that engage in convolution with different kernel that enables the model to capture features of different sizes while the residual links assist in better gradient flow. The Inception modules receive inputs of features at multiple scales and resolution and are consequently capable of identifying detailed patterns in the cassava leaves. The residual connections on the other hand allow training of deeper networks as gradients are allowed to pass through the network with minimal disruption. Another strength of InceptionResNetV2, is Hybrid Architecture. Through the incorporation of the various feature extraction mechanisms that encompass Inception modules together with resilient gradient flow from the residual connections, the model acquires high productivity combined with accuracy. It is seen that this type of design allows the network to handle other complicated image data and even identify very small disease symptoms on cassava leaves41,42.

EfficientNetB3 model has been designed to improve the high-level feature extraction performance while at the same time being computationally effective. The EfficientNetB3 architecture has been replaces some of the standard MBConv blocks with Enhanced MBConv Blocks. These blocks which employ depthwise separable convolution are supposed to learn finer features of the input images. Compared with EfficientNetB0, through tuning the depth and width of the blocks of EfficientNetB3, the model obtains higher accuracy in identifying the feature of cassava leaf images43. This enhancement enables the model to identify and categorize numerous symptoms of disease more effectively than before to distinguish between healthy and infected leaves. The process of Scaling in EfficientNetB3 means an equal increase in the model’s depth, width, and resolution. This type of scaling is balanced which has the effect that the model gains more capacity and resolution and at the same time does not become computationally too expensive. The scaling of the model is improved to enable efficient processing of images with a high resolution or intricate disease presentation since this is essential in the practice of cassava leaf disease detection44.

Performance metrics

While diagnosing the cassava disease, several evaluation metrics assist in the assessment of a classification model such as Accuracy is used to determine the overall performance of the model and it is the ratio of sum of total diseased and total healthy accurately diagnosed to total number of instances. It gives an overall idea about the quality of the model performs among all the classes available. Loss deals with the model’s error by computing the distinctness between the predicted labels and actual labels. If the value of the loss is lowest, it indicates that the model’s prediction is closer to the true values. As this research is based on multiclass classification so categorical cross entropy loss has been used to compute the loss values of model during training and validation phase. Moving to the another set of metrics, Precision identifies the positive instance of a particular disease correctly among all instances. On the other hand, Recall identifies all actual positive cases of a disease. At the end, F1 score provides a balanced view of the model’s performance by combining precision and recall together45,46,47.

Here n = total number of samples, \(\:{y}_{i,c}\:and\:{\widehat{y}}_{i,c}\) = actual and predicted label respectively, C= number of classes

Result and discussion

This section contains the most crucial part of the paper, where the results generated by the models, as discussed in “Applied models” section, are presented after training. It showcases the models’ performance across various metrics (as outlined in “Performance Metrics” section), along with the learning curves, confusion matrix, and the error rates generated during test case.

Table 2 presents the performance analysis of various deep learning models for classification of multiple cassava leaf diseases.

From Table 2, in the training phase, MobileNet V2 demonstrates the highest accuracy at 89.59% while maintaining a low loss of 0.16, indicating its robust performance and efficient learning capability. Xception follows closely with an accuracy of 89.52% and a slightly higher loss of 0.46, suggesting strong predictive ability but with a bit more uncertainty in its predictions compared to MobileNet V2. EfficientNet B0, ResNet50 V2, and ResNet152 V2 each achieve an accuracy of 89.49%, yet their loss values vary significantly, with ResNet152 V2 showing the highest loss at 0.76, which might imply that it struggles more with accurate predictions compared to the others. DenseNet 169 lags with an accuracy of 79.46% and a loss of 0.49, reflecting its relatively lower performance compared to the other models. VGG 19 and InceptionResNetV2 both exhibit decent performance with accuracies of 89.46% and 89.35%, respectively, and comparable loss values of 0.16 and 0.26. Notably, the hybrid model combining DenseNet169 and EfficientNetB0 achieves an accuracy of 89.26% and a loss of 0.26, which is slightly lower in accuracy but shows a good balance between accuracy and loss.

In the validation phase, the Hybrid (DenseNet169 + EfficientNetB0) model excels with the highest validation accuracy of 89.94% and the lowest loss of 0.23, indicating superior performance and stability in validation compared to the other models. MobileNet V2 and DenseNet 169 both achieve a validation accuracy of 89.46%, with MobileNet V2 showing a loss of 0.50, slightly higher than DenseNet169’s 0.491, which might suggest that DenseNet 169 has a marginally better generalization on the validation set. Xception also performs well, with an accuracy of 89.26% and a notably low loss of 0.19, indicating it maintains strong predictive performance with minimal uncertainty. EfficientNet B0 and ResNet152 V2 both exhibit an accuracy of 89.49%, but their losses are higher, at 0.76 and 0.60 respectively, suggesting that these models might have a higher degree of prediction error on the validation set. VGG 19 shows a balanced performance with an accuracy of 89.46% and a loss of 0.29, reflecting stable results across the validation data. In contrast, Inception V3 and InceptionResNetV2 show lower accuracy values of 88.23% and 87.59%, respectively, with InceptionResNetV2 having a higher loss of 0.59, indicating that these models struggle more with generalization on the validation set.

Overall, the results reveal that EfficientNetB0, MobileNetV2, and DenseNet169 exhibit strong overall performance with high accuracy and low loss values during training. EfficientNetB0 and MobileNetV2 achieve the highest accuracy rates with low training loss. The hybrid model combining DenseNet169 and EfficientNetB0 achieves the highest as well as lowest validation accuracy and loss respectively, indicating superior generalization and performance. In contrast, models like InceptionV3 and InceptionResNetV2 show a drop in validation accuracy compared to training accuracy, which suggests overfitting or other model-specific issues.

Figure 19 displays two graphs that illustrate the training and validation performance of applied learning models over 10 epochs. The left graph shows the training and validation loss, where the red line represents the training loss, and the green line represents the validation loss. The right graph depicts the training and validation accuracy, with the red line representing the training accuracy and the green line representing the validation accuracy.

The training loss of the models begins at relatively high values, ranging from 5 to 13, but decreases steadily throughout the epochs, reaching between 0 and 6 by the 10th epoch. In contrast, the validation loss also decreases but at a slower rate, starting around 5 and reducing to about 2 by the end of the training process. The optimal validation loss is marked at epoch 10, indicating the best performance for validation. Notably, some models, such as DenseNet169, MobileNetV2, and VGG19, exhibit higher initial validation losses around 8. Xception starts with an even higher validation loss of approximately 11, reflecting an initial gap between training and validation performance and a noticeable disparity in the loss curves across epochs. This suggests that Xception faced challenges in generalization early on. Additionally, models like ResNet152V2, MobileNetV2, and VGG19 show a significant gap between their training and validation loss curves throughout the epochs, which may indicate overfitting. In contrast, models such as EfficientNetB3, InceptionResNetV2, InceptionV3, ResNet50V2, DenseNet169, and EfficientNetB0 demonstrate more stable and favorable performance, with their validation loss curves converging more closely with their training loss curves. These observations suggest that while some models struggle with convergence and overfitting, others exhibit better generalization capabilities and stability.

On the other hand, In EfficientNetB0, the training accuracy begins relatively low at around 0.5 but increases rapidly, approaching 1 by the 10th epoch. The validation accuracy starts around 0.7, fluctuates, peaking near 0.8, and then stabilizes. The best validation accuracy is marked at epoch 9. In contrast, DenseNet169 starts with validation accuracy below 0.2, which gradually improves to between 0.6 and 0.7 by the 10th epoch. The accuracy curve exhibits substantial fluctuations, with notable peaks at epochs 3 and 8. Xception demonstrates a significant gap between training and validation accuracy, achieving a training accuracy of 0.95 while validation accuracy lags at 0.70, indicating issues with generalization. MobileNetV2 shows its peak validation accuracy at the 3rd epoch, but both training and validation accuracy curves diverge thereafter. ResNet152V2 starts with a low training accuracy of around 0.28, which steadily increases to about 0.5 by the 5th epoch. The validation accuracy, represented by the green line, starts higher at around 0.55, peaks at 0.6 around epoch 4, but then drops sharply by the 5th epoch. This drop suggests potential overfitting, where the model’s performance on unseen data declines despite improved training accuracy. Among the remaining models, such as VGG19, EfficientNetB3, ResNet50V2, InceptionV3, and InceptionResNetV2, there is overall improved performance, but some divergence between training and validation metrics suggests possible overfitting.

Additionally, the performance analysis of the models based on precision, recall, and F1 score reveals varying levels of effectiveness, and its values are presented in Table 3.

EfficientNetB0 stands out with balanced precision, recall, and F1 score, all at 0.78, indicating a consistent and reliable performance across these metrics. DenseNet169 shows strong recall (0.78) and precision (0.76), but its F1 score drops significantly to 0.51, suggesting it struggles with balancing precision and recall, possibly due to a large disparity between true positives and false positives/negatives. Xception, VGG19, and InceptionV3 all demonstrate balanced performance with precision, recall, and F1 score around 0.72–0.73, reflecting stable generalization across the metrics. MobileNetV2 shows an imbalance, with a reasonable precision of 0.73, but its recall is significantly lower at 0.50, resulting in an F1 score of 0.54, indicating the model is good at correctly predicting positives but misses a significant portion of actual positive instances. ResNet50V2 performs well with a precision of 0.78, but its recall is lower at 0.67, leading to a moderately strong F1 score of 0.69, reflecting some trade-off between precision and recall. On the other hand, ResNet152V2 and InceptionResNetV2 show poor performance, with both models having low precision (0.57), recall (0.36), and F1 score (0.40), indicating they struggle to correctly classify instances and generalize poorly on unseen data. Finally, EfficientNetB3 matches the precision (0.78) of EfficientNetB0, but its recall (0.67) is lower, resulting in a lower F1 score of 0.69, suggesting that while it makes accurate predictions, it may miss a significant number of true positives.

Table 4 exhibits the performance of the models employed in the process of detection of multiple cassava plant disease based on precision, recall and F1 score.

In case of Cassava Bacterial Blight, between the two models, InceptionResNetV2 and ResNet152V2 show high precision at 0. 87, recall of 0. 88 and the F1 score of 0. 82 thereby showing robustness in this classification task. Xception and InceptionV3 also enables good result with F1 score of 0. 86 and the precision-recall values are near to 0. 82 − 0. 81 proving how reliable these models are in determining the disease is. MobileNetV2 can be considered also very efficient having an F1 score of 0. 78, and a recall value of 0. 88 However, the precision of this number is slightly lower, and stands at 0. 73, implying that it gets the positive one right while, in the process, it may get some incorrect. DenseNet169 and EfficientNetB3 are also moderate with the F1 scores of 0. 79 and 0. 76 respectively which is fair accuracy in the classification of the disease. EfficientNetB0, while achieving a good high recall of 0. 86 and, the precision rate of the method demonstrated at 0. 44 produced lower F1 score of 0. 89 which suggests most of the cases it predicts high positives. At the lower end of the performances, ResNet50V2 and VGG19 perform particularly poorly with a low F1 score of 0. 46, precision of 0. 52, and a recall score of 0. 41. Resnet50V2 has a reasonably high F1 score of 0. 86 demonstrates high loss rate which is equal to 0. 54; it is a sign that the model fails to recognize a vast amount of positively labelled instances.

In case of Cassava Brown Streak Disease, the models which show the best performance features are InceptionV3 and Xception where the F1 score is 0. 89, and of the same level of precision – 0. 89. These models proved to possess high reliability when classifying both positive and negative instances, but there is moderate recall rate of 0. 65 meaning that they tend to overlook some actual positives. ResNet152V2 and InceptionResNetV2 algorithms are equally efficient as they have precision, recall, and F1-score equalling 0. 80. Right behind is the ResNet50V2 which also has a relatively high F1 score of 0. 84, a good recall of 0. 82 and a good precision of 0. 74 for most of the cases, although it may be slightly off on classifying cases. MobileNetV2 while has a remarkable recall of 0. 89 and the precision is at 0. 40 with the F1 score as 0.88. This means most of the positive cases are predicted correctly by the model while most of the non-disease cases are incorrectly classified hence high false positives. On the other hand, efficient net B3 and efficient net B0 give balanced but relatively average performance as they have F1 score (0. 74 as well as 0. 64), respectively. These models reasonably well on the reliability range but still less than those at the top of the charts. DenseNet169 yields the lowest F1 score of 0. 55, recall of 64% and precision of 0. 79. It shows that the model performs well on the positive cases but poor performance on disease cases and thus a lower capability to classify than the other algorithms. Lastly, VGG19 has the lowest F1 score of 0. 49 due to low precision 0. 39 and moderate recall 0. 65. This model’s performance for classifying the disease is not very good, it tends to give more false positives and has found to be less accurate than other models.

When evaluating for Cassava Green Mottle, all the models have variations in the precision, recall and F1 score. Last but not the least, InceptionResNetV2 and ResNet152V2 models score the total accuracy of the precision equal to 0. 82, recall as 0.83 as well as F1 score as 0. 89. The findings of the above models are good and give consecutive results with excellent results of both providing the right number of positive cases and false positives. Xception is a bit close with regards to the F1 score with a measure of 0. 84 with a high precision of 0. 90 and recall of 0. 87 represents it as one of the best performing models which is least likely to misclassify the disease. MobileNetV2 was also ranked high with F1 score of 0. 85, precision of 0. 83, while recall is slightly lower and equal to 0. 68. Though it is very accurate, it could lower detection of true positive cases leading to concerns to its reliability. InceptionV3 works well in classification as it has high recall of 0. 81 and the F1 score of 0. 84 but the precision of only 0. 47. This makes suggest that while it is highly effective at predicting true positives but at the same time the model is also highly prone to false positives, giving its predictions low precision. EfficientNetB0 provides approximately precision of 0. 83, 0.62 as recall, and F1 score of 0. 57, which prove that the given method tends to fail to classify all positive instances, although in the beginning it classifies them with a relatively low rate of error. DenseNet169 is moderate and yet again the precision sits at 0. 71, recall of 0.47 but with high F1 score of 0.82. This all points to a relatively high variance between true positive and true negative rates which render the model quite inconsistent. ResNet50V2 and EfficientNetB3 have moderate to low results with a higher level of the false positive rate with lower precision of 0. 58 and a recall of 0. 47, while having a relatively higher F1 score of 0. 82 which means that it is likely to misclassify most of the negatives. EfficientNetB3 obtained F1 score 0. 72, yet it yields low accuracy in terms of both precision and, even more so, recall. VGG19 achieved the lowest accuracy of 0. 47 for precision and 0. 41 for recall while its F1 score was of 0. 44, which is the lowest for the given model in terms for identification of Cassava Green Mottle.

For the detection of Cassava Mosaic Disease, EfficientNetB0 has the highest value of precision with 0. 91, recall of 0. 89, and F1 score at 0. 90. This indicates that the model correctly identifies the positive cases and coupled with the low value for FPR makes this the best balanced and most accurate model for this purpose. It is clearly seen that performances of DenseNet169, Xception, VGG19, and InceptionV3 are quite close to each other with having the precision value of approximately 0. 88 to 0. 90, recall of 0. 75, precision of 0.85, recall of 0.87, and an F1 score of 0. 88 respectively. These models are very accurate at identifying the disease thus giving a very stable classification whereby precision and recall are not traded off heavily. MobileNetV2 also has the exactness value of precision this is equal to 0. 94, while the recall of the same model is reduced to 0. 85, that makes the F1-score much lesser than in the previous case, equal to 0. 61. This shows that while, it is very effective in correctly classifying a high percentage of the positive cases, its low recall means that it misses on more actual positives hence compromising on the overall accuracy of the classification. Finally, it is worthy of checking the achieved level of precision: For ResNet50V2 it is 0. 93 but the recall of the subjects reduces to 0. 76 resulting in an F1 Score of 0. 84. In general, these models are accurate in terms of the precision and recall, but to achieve this, the recall factor is compromised making them capable of leaving out positive cases while at the same time ruling out all the negative cases. InceptionResNetV2 and ResNet152V2 achieved almost equal recall values of 0. 88, however, InceptionResNetV2 is found to be more accurate with a balanced F1 score of 0. 82 while ResNet152V2 gave F1 score of 0. 52. It is because the latter has a lower F1 score with a precision of only 0. 81 thus the difference between the total number of correctly identified cases and false positive number is much large.

In the case of the Healthy samples, Xception computed the 0. 86 precision, 0. 80 recall, and 0. 83 F1score. This suggests a good balance of true positive rates over false positive rates which make this tool very reliable. InceptionV3 as well as ResNet50V2 have a moderately high value of F1 Score at 0. 83. In InceptionV3, the precision is comparatively low at 0.46 but the recall is high at 0.80 implying that most true positives are identified while for ResNet50V2, the precision is 0.89; recall is slightly low at 0.78. These models give high accuracy in either precision or recall that resulting in high overall accuracy. ResNet152V2 and InceptionResNetV2 are on equal ranking – The precision is close to 0. 83, recall of 0. 82 and F1 scores of 0. 82. They have good levels of accuracy and completeness and are recommended for healthy instance identification with minimal prejudice of false positive or false negatives. MobileNetV2 is rather remarkable in question of recall that is 0. 89 and rather low precision is 0. 81 that resulted in F1 score 0. 54. It effectively recognises most true positives but at the same time overly generates many false positives thus reducing on its accuracy. EfficientNetB0 makes a reasonable performance with the precision of 0. 87 with recall being at 0. 59, that in average achieved an F1 score equal to 0. 58. DenseNet169 has relatively balanced, but less accuracy and a lower precision is slightly less, 0. 76, recall of 0. 78, and F1 score of 0. 51. However, its F1 score indicates that it is not of high clarity in the classification of cases, especially the healthy ones. EfficientNetB3 is almost equivalent to the DenseNet169, with 0.79 as precision, 0. 78 as recall, and 0. 72 as F1 score. It is slightly more balanced and nonetheless not superior to Xception and ResNet derivatives. VGG19 is the weakest performer, with low precision (0.46), recall (0.40), and an F1 score of 0.43. It struggles significantly with both precision and recall, making it less suitable for classifying healthy instances.

Table 5 highlights the error distribution across different cassava leaf disease classes. The highest misclassification rate was observed in the Cassava Mosaic Disease (CMD) class, with nearly 300 errors. This indicates a challenge for models in distinguishing CMD, possibly due to overlapping visual features with other diseases or limited CMD-specific training data. Cassava Green Mottle (CGM) and Healthy classes also showed noticeable errors, albeit at lower levels compared to CMD. This could be attributed to variability in leaf appearance caused by environmental factors, which the models might struggle to generalize. In contrast, Cassava Brown Streak Disease (CBSD) and Cassava Bacterial Blight (CBB) exhibited the fewest errors, suggesting that these classes have distinct features enabling the models to achieve higher classification accuracy.

These findings emphasize the need for improved data representation, particularly for classes with high error rates, and further fine-tuning of the models to enhance their ability to differentiate overlapping features across classes.

Moreover, as shown in Fig. 20, the performance of the model that outperformed the others has also been evaluated in predicting the class of Cassava leaf disease for random images to assess its generalization.

Apart from this, in this section, the underperformance of certain models has been also seen because of the various factors related to their architecture, dataset characteristics, and task-specific challenges. Architecturally, deeper networks such as ResNet152V2 and InceptionResNetV2, while capable of learning complex patterns, are more prone to overfitting due to their high parameter counts, as evidenced by their drop in performance between training and validation phases. This issue is compounded by the dataset’s imbalance, where underrepresented disease classes skew the models’ learning process, leading to biased performance. Lightweight architectures like MobileNetV2, although computationally efficient, struggle to capture the subtle differences between disease classes due to their simplified feature extraction mechanisms, resulting in lower accuracy. Additionally, while preprocessing techniques like noise reduction and segmentation improve image quality, not all models, particularly those with basic feature extraction layers, effectively leverage these enhancements. The hybrid DenseNet169 + EfficientNetB0 model, on the other hand, excels by combining DenseNet’s robust feature reuse capability with EfficientNet’s computational efficiency, achieving superior generalization and performance. However, resource-intensive models like InceptionV3 and ResNet50V2, despite their strong performance, may face limitations in real-world scenarios due to their high computational demands. These findings highlight the critical interplay between model design, data quality, and task complexity, suggesting that future work should focus on strategies like data augmentation, class-weighted loss functions, and ensemble learning to address these challenges effectively.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have successfully implemented deep learning techniques for detecting and classifying diseases in cassava plants using multiple transfer learning architectures. Our approach analyzed images of cassava leaves affected by diseases such as Cassava Green Mottle, Cassava Bacterial Blight, Cassava Mosaic Disease, Cassava Brown Streak Disease, alongside healthy leaves. Among the tested models, EfficientNetB3, Xception, InceptionV3, and ResNet50V2 performed well, but the hybrid model combining DenseNet169 and EfficientNetB0 achieved superior accuracy. The models were evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score, collectively demonstrating their effectiveness in distinguishing between healthy and diseased leaves. These findings highlight the potential of deep learning in providing a scalable and robust framework for real-time cassava disease detection, offering significant benefits for agricultural practices.

Automating the disease detection process can enable farmers and agricultural experts to monitor crop health efficiently, allowing for early detection, timely interventions, and reduced crop losses. This can ultimately contribute to food security and economic growth in cassava-dependent regions. However, certain challenges were encountered, including class imbalance, where some diseases were underrepresented, leading to biased models favoring more frequent classes. Additionally, variations in image quality and environmental conditions impacted model generalizability, while some models showed signs of overfitting, performing well on training data but less effectively on validation data. Addressing these limitations in future work is crucial to improving model performance. Increasing dataset diversity by incorporating images from different regions and cassava varieties, along with employing techniques to mitigate overfitting, would enhance model robustness and reliability.

Furthermore, the proposed framework could be adapted for real-time implementation by integrating the disease detection system with mobile applications, drones, or IoT-enabled devices, enabling on-field monitoring and diagnosis for large-scale farming operations. By leveraging advancements in deep learning, this study presents a scalable and impactful solution for sustainable agricultural management, paving the way for technology-driven approaches to tackle critical challenges in agriculture.

Data availability

The data used in this study is publicly available at the following link: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/cassava-leaf-disease-classification/data.

References

Brimer, L. Cassava Production and Processing and Impact on Biological Compounds. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 81–87). (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-404699-3.00010-x

Shaik Khajavali, M. L., Sneha Snigdha, P., Roshini, B., Srilakshmi, A. & Gopi, B. D. H. Developing of CNN Model for Disease Detection on Cassava leaves using VGG-16 algorithm. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. Eng. 12 (3), 2366–2379 (2024).

https://www.krungsri.com/en/research/industry/industryoutlook/agriculture/cassava/io/cassava-2024-2026

Global Cassava Processing Market to Grow at 1.4% During 2024–2032. (2020). https://www.imarcgroup.com/global-cassava-processing-market

Emmanuel, A., Mwangi, R. W., Murithi, P., Fredrick, K. & Danison, T. Classification of cassava leaf diseases using deep gaussian transfer learning model. Eng. Rep., 5(9), 1-13. (2023).

Khakimov, A., Salakhutdinov, I., Omolikov, A. & Utaganov, S. Traditional and current-prospective methods of agricultural plant diseases detection: A review. In IOP Conference series: earth and environmental science (Vol. 951, No. 1, p. 012002). IOP Publishing. (2022).

Uke, A. et al. Cassava mosaic disease and its management in Southeast Asia. Plant Mol. Biol.. 109, 301–311 (2022).

Jafar, A., Bibi, N., Naqvi, R. A., Sadeghi-Niaraki, A. & Jeong, D. Revolutionizing agriculture with artificial intelligence: plant disease detection methods, applications, and their limitations. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1356260 (2024).

Lokesh, G. H. et al. A. Intelligent Plant Leaf Disease Detection using Generative Adversarial networks: a case-study of Cassava leaves. Open. Agric. J., 18(1). 1-15 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Land use policy implications of demographic shifts: analyzing the impact of aging rural populations on agricultural carbon emissions in China. Land. Use Policy. 147, 107340 (2024).

Alford, J. & Tuba, E. Cassava Plant Disease Detection Using Transfer Learning with Convolutional Neural Networks. In 2024 12th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024), April.

Singh, R., Sharma, A., Sharma, N., Sharma, K. & Gupta, R. A Deep Learning-Based InceptionResNet V2 Model for Cassava Leaf Disease Detection. In International Conference on Emerging Trends in Expert Applications & Security (pp. 423–432). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2023), February.

Zhang, J. et al. MAIANet: signal modulation in cassava leaf disease classification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 225, 109351 (2024).

Ravi, V., Acharya, V. & Pham, T. D. Attention deep learning-based large‐scale learning classifier for Cassava leaf disease classification. Expert Syst. 39 (2). https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.12862 (2021).

Sholihin, M., Fudzee, M. F. M. & Ismail, M. N. AlexNet-Based feature extraction for Cassava classification: a Machine Learning Approach. Baghdad Sci. J. 20 (6 (Suppl.)), 2624–2624 (2023).

Haq, S. I. U., Raza, A., Lan, Y. & Wang, S. Identification of Pest Attack on Corn crops using machine learning techniques. Eng. Proc. 56 (1), 183 (2023).

Haq, S. I. U., Tahir, M. N. & Lan, Y. Weed detection in wheat crops using image analysis and artificial intelligence (AI). Appl. Sci. 13 (15), 8840 (2023).

Prashanth, J. S. et al. MPCSAR-AHH: a hybrid deep learning model for real-time detection of cassava leaf diseases and fertilizer recommendation. Comput. Electr. Eng. 119, 109628 (2024).

Lilhore, U. K. et al. Enhanced convolutional neural network model for Cassava Leaf Disease Identification and classification. Mathematics 10 (4), 580. https://doi.org/10.3390/math10040580 (2022).

Sapre, M., Jatti, V. S., Tiwari, P., Kodachakki, N. & Undale, A. Disease classification in Cassava Plant by Artificial neural network. In Machine Learning and Optimization for Engineering Design by Apoorva S. Shastri, Kailash Shaw, Mangal Singh (75–84). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2023).

Lanjewar, M. G. & Parab, J. S. CNN and transfer learning methods with augmentation for citrus leaf diseases detection using PaaS cloud on mobile. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83 (11), 31733–31758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-16886-6 (2023b).

Panchbhai, K. G., Lanjewar, M. G., Malik, V. V. & Charanarur, P. Small size CNN (CAS-CNN), and modified MobileNetV2 (CAS-MODMOBNET) to identify cashew nut and fruit diseases. Multimedia Tools Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-024-19042-w (2024).

Lanjewar, M. G., Morajkar, P. & P, P. Modified transfer learning frameworks to identify potato leaf diseases. Multimedia Tools Appl. 83 (17), 50401–50423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-023-17610-0 (2023).

Cassava Leaf Disease Classification. (n.d.). Kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/cassava-leaf-disease-classification/data

Fennell, J. et al. A method for real-time classification of insect vectors of mosaic and brown streak disease in cassava plants for future implementation within a low-cost, handheld, in-field multispectral imaging sensor. Plant. Methods. 14, 1–12 (2018).

Dhasan, D. B., Karthik, K., Reddy, M. L. & Yadav, M. G. S. Identification and classification of cassava plant leaf disease using deep learning technique. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2519, No. 1). AIP Publishing. (2022), October.

Sangbamrung, I., Praneetpholkrang, P. & Kanjanawattana, S. A novel automatic method for cassava disease classification using deep learning. J. Adv. Inform. Technol. Vol. 11 (4), 241–248 (2020).

Tusubira, J. F., Akera, B., Nsumba, S., Nakatumba-Nabende, J. & Mwebaze, E. Scoring root necrosis in cassava using semantic segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.03367. (2020).

Shahriar, H., Shuvo, P. S., Fahim, M. S. H., Sordar, M. S. & Haque, M. E. Cassava leaf disease classification using deep learning and convolutional neural network ensemble (Doctoral dissertation, Brac University). (2022).

Ahmad, A., El Gamal, A. & Saraswat, D. Toward generalization of deep learning-based plant disease identification under controlled and field conditions. IEEE Access. 11, 9042–9057 (2023).

Paiva-Peredo, E. Deep learning for the classification of cassava leaf diseases in unbalanced field data set. In International Conference on Advanced Network Technologies and Intelligent Computing (pp. 101–114). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. (2022), December.

Rani, B. V. N. et al. Plant Disease Detection and Classification with Deep Learning. (2021).

Gómez-Pupo, S. M., Patiño-Saucedo, A., Agudelo, M. A. F. & Mesa, E. C. & Patiño-Vanegas, A. Convolutional neural networks for the recognition of diseases and pests in Cassava leaves (Manihot esculenta).

Surya, R. & Gautama, E. Cassava leaf disease detection using convolutional neural networks. In 2020 6th international conference on science in information technology (ICSITech) (pp. 97–102). IEEE. (2020), October.

Kiruthika, V., Shoba, S., Madan, S., Kishore, S. & Punetha, D. Hybrid ensemble-deep transfer model for early cassava leaf disease classification. Heliyon. (2024).

Hessane, A., Boutahir, M. K., Youssefi, E., Farhaoui, A., Aghoutane, B. & Y., & Empowering date Palm Disease Management with Deep Learning: a comparative performance analysis of Pretrained models for Stage-wise White-Scale Disease classification. Data Metadata. 2, 102–102 (2023).

Varma, T., Mate, P., Azeem, N. A., Sharma, S. & Singh, B. Automatic mango leaf disease detection using different transfer learning models. Multimedia Tools Appl. 17, 1–34. (2024).

Sharma, M., Rastogi, M., Srivastava, P. & Saraswat, M. Intelligent pesticide recommendation system based on plant leaf disease and pests. In International Conference on Advancements in Interdisciplinary Research (pp. 352–361). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. (2022), May.

Ramcharan, A. et al. Deep learning for image-based cassava disease detection. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1852 (2017).

Rajalakshmi, R., Shinow, A. B., Murali, A., Nair, K. S. & Bhuvana, J. An efficient convolutional neural network with Image Augmentation for Cassava Leaf Disease Detection. In Recurrent Neural Networks by Amit Kumar Tyagi, Ajith Abraham (289–305). CRC. (2022).

Mohanraj, G., Prabakaran, K. & Rajkumar, M. Comparative Study on Cassava Leaf Disease Classification. In 2024 Second International Conference on Emerging Trends in Information Technology and Engineering (ICETITE) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024), February.

Karthik, R. et al. A deep feature fusion network using residual channel shuffled attention for cassava leaf disease detection. Neural Comput. Appl. 35 (30), 22755–22770 (2023).

Saleki, S. & Tahmoresnezhad, J. Agry: a comprehensive framework for plant diseases classification via pretrained EfficientNet and convolutional neural networks for precision agriculture. Multimedia Tools Appl. 1, 39 (2024).

Gopi, A. Disclosing the Potential of Deep Learning in Cassava Leaf Disease Analysis by using CNN and Neural Networks Approach. In 2024 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT) (pp. 188–193). IEEE. (2024), April.

Changela, A., Kumar, Y. & Koul, A. Machine Learning-based Approaches for Crop Recommendations and Prediction. In 2023 International Conference on Communication, Security and Artificial Intelligence (ICCSAI) (pp. 370–376). IEEE. (2023), November.

Kumar, Y., Singh, R., Moudgil, M. R. & Kamini A systematic review of different categories of plant disease detection using deep learning-based approaches. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 30 (8), 4757–4779 (2023).

Kanna, G. P. et al. Advanced deep learning techniques for early disease prediction in cauliflower plants. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 18475 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Xiamen University Malaysia (XMUM) under the XMUM Research Fund (XMUMRF) (Grant number: XMUMRF/2024-C13/IECE/0051).

Funding

This work was supported by Xiamen University Malaysia (XMUM) under the XMUM Research Fund (XMUMRF) (Grant number: XMUMRF/2024-C13/IECE/0051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. Sambasivam: Drafted the article, designed the experiments, and contributed to methodology development. G. Prabu Kanna: Conducted model training and optimization and contributed to data analysis. Munesh Singh Chauhan: Handled the preprocessing techniques and image segmentation tasks. Prem Raja: Worked on model evaluations and helped with statistical validation of results. Yogesh Kumar: As corresponding author, critically revised the manuscript and ensured research integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sambasivam, G., Prabu kanna, G., Chauhan, M.S. et al. A hybrid deep learning model approach for automated detection and classification of cassava leaf diseases. Sci Rep 15, 7009 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90646-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90646-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Leveraging retinanet based object detection model for assisting visually impaired individuals with metaheuristic optimization algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhancing citrus crop protection via hybrid CNN model combining EfficientNetB0 and MobileNetV2

International Journal of Information Technology (2025)