Abstract

Separated endodontics instruments and high-density obturating materials produce metal artifacts on cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scans. This study evaluated a novel methodology to detect separated instruments using artifact suppression and color map algorithms with CBCT post-processing software and compared with periapical radiographs (PRs). Endodontic instruments were incorporated into 168 root canals filled with four sealers. Additionally, 40 root canals were only filled, serving as control. CBCT scans were acquired in PreXion-3D-Elite, and digital PRs were taken in distoradial, mesioradial, orthoradial, and proximal directions. The treated teeth were analyzed using an artifact suppression algorithm combined with a color map algorithm. The separated instruments appear in the color map with larger expansion in red to allow identification. This map provides valuable information by showing dynamic visualization toward the point of expansion of the high-density object, hence suggesting a separated instrument. The chi-square test was used to compare the separated instruments among the imaging methods. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was considered P < 0.05. Overall, CBCT performed significantly better than PRs (P < 0.001) in detecting separated instruments. PR was influenced by all the variables studied (P < 0.05). The artifact suppression and color map algorithms, combined with dynamic navigation, effectively identified separated instrument fragments in all the root canal fillings, regardless of filling material, image view, or root canal. Only 32.3% of the root canal fillings viewed by PR detected separated instrument fragments. This method seems to be useful in the resolution of the problem of viewing separated instruments with CBCT post-processing software.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clinical procedures for root canal treatment (RCT) are complex to manage, since they involve several challenges that can lead to accidents or errors during any operative process1. It is crucial to categorize important clinical factors ongoingly so that potential difficulties can be identified during RCT. Retained separated endodontic instruments inside the root canal are considered a clinical complication that must be well assessed and prevented, since they can impact the therapeutic outcome adversely2,3,4,5. Because they represent an unpredictable event, the real impact on the prognosis is associated with several aspects, which include the clinical condition prior to treatment (inflamed or infected pulp tissue), presence of apical periodontitis, sinus tract, symptoms, the moment the instrument separates in the treatment process (start of, midway through, or after disinfection), location of the separated instrument (cervical, middle or apical third), the type, length and size of the instrument fragment, the anatomical complexity of the teeth (anterior teeth, premolars, molars; curved, straight, or flat canals), etc1,2,3,4,5.

Currently, there are over 200 different models of manual stainless steel and nickel-titanium (NiTi) engine-driven instruments available on the dental market6. They must be selected carefully, making sure to ascertain their characteristics, manufacturing processes, and quality control. Their large supply (hence variable quality) on the global market makes them inevitably prone to risk factors that influence their quality. These factors have been reported in the literature, which has exposed low-cost instruments that are ineffectual in improving functionality6.

The retained fragment creates a barrier that hinders full access to the canal for proper emptying, enlargement, irrigation and decontamination, and for complete sealing of the root canal system. The impact of this operative complication on the prognosis is attributed to potential RCT failures3,4,5. The success rate in recovering separated instruments ranges due to several factors, including the visibility of the separated instrument, the length of the separated instrument in relation to the curvature of the root canal, the degree of infection of the canal and the periapical region, and the techniques applied to each specific case1,5. The future outcome of separated instrument recovery should focus on managing non-visible separated instruments, since the removal of these instruments is considered unpredictable using current techniques. In contrast, the removal of visible separated instruments may have a more predictably favorable recovery7. Separated instruments may not affect the prognosis of endodontically treated teeth when there is no periapical infection1,5,8. However, in the presence of the disease, the healing process is significantly reduced4. Decisions on how separated instruments should be managed should take the following factors into account8: the limitations of the root canal in accommodating the fragment, the location where the instrument separated during root canal preparation, the clinician’s skill level, the available tools, the potential complications of the chosen treatment approach, the importance of the affected tooth (chewing efficiency, aesthetic function, etc.), and whether there is periapical pathosis8.

Accidental fragment separation hinders complete access to and disinfection of the root canal system during the RCT. Once the separated fragment of an endodontic instrument has been identified, new strategic planning is essential for RCT to proceed1,5. Imaging exams have been routinely used before, during, and after RCT5,9. The routine use of conventional two-dimensional imaging models for three-dimensional structures in RCT can lead to misinterpretation. Periapical lesions may be present but not identified, thus remaining hidden and not visible on periapical radiographs. Diagnostic accuracy plays a critical role in the success of the therapy9,10.

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is an imaging examination that has been integrated into clinical dental practice11, and has greatly improved the accuracy of clinical diagnoses, as opposed to traditional 2D examinations10,11. In complex cases involving internal anatomy, CBCT has become a benchmark examination due to its ability to identify important anatomical areas, periapical lesions, root resorption, and root fracture lines12,13,14,15.

Although CBCT exams offer several advantages compared with periapical radiographs10,11,12,13,14,15, high-density materials (solid dental structures or metal objects) can lead to metal artifacts16,17,18,19, which can compromise the quality of the image and ultimately result in diagnostic errors. Metal artifacts manifest as distortions in CBCT images and affect the gray tones and fidelity to actual structures, thereby reducing image quality, and making diagnosis challenging. The beam hardening effect occurs when X-ray beams pass through high-density materials, causing differential attenuation, and resulting in various types of metal artifacts caused by both beam hardening and scattered radiation16,17,18,19.

Gutta-percha and endodontic sealers are the materials commonly used to fill root canals. These materials are made up of several chemical elements that have varying molecular weights and high density, and that often produce high density artifacts in CBCT images, with volumetric expansion coefficients, striae and dark bands20,21,22,23. Studies have been conducted to minimize these issues and ensure that CBCT images accurately represent the true structures of root canals to maintain precise diagnoses20,21,22,23,24,25,26. In addition to root canal filling materials, intrarradicular posts and other metal materials, such as separated endodontic instruments, may be responsible for the loss of detail in CBCT images, and obscure correct interpretation of imaging examinations22,25,26.

Some studies27,28,29,30 have shown that periapical radiographs perform better than CBCT scans in detecting separated endodontic instruments in teeth that have undergone endodontic treatment. Any complication can be a risk factor for RCT failure1; however, a separated instrument inside a root canal is very concerning and challenging to resolve31. Nonetheless, longitudinal clinical studies on separated endodontic instruments, and on the outcome of managing endodontic problems are scarce31,32. Findings that contrast with what has been observed in studies involving clinical practice point to the accurate identification of a retained separated endodontic instrument provided by imaging examinations with CBCT scans compared with periapical radiographs. This result motivated the implementation of a metal artifact reduction algorithm, the creation of a color map algorithm, and a millimeter-based dynamic navigation strategy along the root canal to identify more accurately the retained separated instrument fragment inside the root canal filling material.

This study described a novel methodology to detect separated endodontic instruments using artifact suppression and color map algorithms with CBCT post-processing software and compared with periapical radiographs (PRs).

Material and method

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Federal University of Goiás (#06486919.0.0000.5083). All the participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample selection

The samples used in the present study were obtained from an image database collected during the study conducted by Sousa et al.33. First, the root canals were filled with various root canal sealers, and then analyzed to determine the potential of CBCT scans versus PR to identify the retained separated instruments in the root canal filling materials. The method used artifact reduction and color map algorithms, with a dynamic navigation strategy.

Analysis of the sample size showed that a minimum sample of 34 specimens was recommended (G*Power software version 3.1.2, an alpha error probability of 0.05, and 80% power; effect size = 0.5, University of Düsseldorf, Germany). The study employed mesiobuccal and mesiolingual root canals of eighty-four mandibular molars extracted for various reasons and preserved in 0.1% thymol. Thus, a total of 104 mandibular molars (208 root canals, MB and ML) were used in this study. Endodontic instruments were incorporated into 84 teeth (168 root canals) that were filled with four different sealers, distributed into 4 groups of 21 teeth each. Additionally, 20 teeth (40 root canals, 5 teeth per sealer) were only filled, serving as a control group. A total of 728 views was examined in PRs, distributed as follows: distoradial (2 views, MB, ML), mesioradial (2 views, MB, ML), orthoradial (1 view, MV/ML overlap), and proximal (2 views, MB, ML) (n = 84 + 20 = 104 × 7 = 728). The reference points for dynamic navigation in the analysis for CBCT exams (728 views) were the same as those established for the PRs examinations.

Subsequently, the teeth were removed from the thymol solution and submerged in 5% sodium hypochlorite for 30 min to remove external organic tissues. The teeth were radiographed and submitted to the inclusion criteria, determined as teeth with a healthy root structure, complete root development, two root canals in the mesial root, absence of root canal treatment, internal or external resorptions, calcifications, abnormal tooth development, perforations, or visible signs of fractures and cracks.

Root canal filling and preparation

The mandibular molar crowns were opened to gain root access, and all the root canals were emptied and enlarged up to 400 μm using nickel-titanium (NiTi) engine-driven instruments. The patency was established using a #15 K-file. The mesiobuccal and mesiolingual root canals were irrigated with a 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution, with the tip of the instrument 2 mm short of the working length. The root canals were dried and filled with 17% EDTA for 3 min to remove the smear layer. After root canal preparation, all the teeth were randomly distributed into groups (n = 21), based on the root canal filling materials tested: Sealapex® (Sybron Endo, Orange, CA), AH Plus® (Dentsply, De Tray, Konstanz, Germany), Endofill® (Dentsply, Petropolis, Brazil), and Bio C-sealer (Angelus, Londrina, Brazil). Stainless steel hand files (#25 to 30 K-Files, Dentsply Sirona, Ballaigues, Switzerland), and nickel-titanium engine-driven instruments (Protaper Next X2 #25, X3 #30, Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) were cut 2 mm from the tip using a double-sided diamond disc. These separated instruments had previously been used in the root canal preparations performed for the pre-clinical laboratory course, and were unused stock. A fragment of these instruments was randomly placed 5 mm from the tip of each size 40.04 main gutta-percha point (Dentsply Maillefer, Sirona, Switzerland). Subsequently, the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual canals were obturated using the lateral condensation technique, and one of the sealers was evaluated. The endodontic sealers were manipulated according to the recommendations provided by their respective manufacturers. The root canals were filled using the lateral condensation technique and calibrated gutta-percha points size 40.04 (Dentsply Maillefer, Sirona, Switzerland). Twenty mesial roots (five of each root canal sealer) served as control, with no fractured instrument. Figure 1 shows the flowchart illustrating the experimental design.

Acquisition of the imaging exams

Digital PRs were obtained from each tooth that had undergone endodontic treatment using the Focus Periapical Unit (0.7 mA, 70 KVp, 2.5 mm Al, exposure time of 0.2 s, focal spot 0.7 mm [IEC 60336], KaVo Dental, Bieberich, Germany). The images were processed with the plate reader from the same manufacturer. The radiographs were standardized using a special platform for both root canals (mesiobuccal and mesiolingual) to ensure a parallel procedure. PRs were obtained in the distoradial, mesioradial, orthoradial, and proximal directions.

The CBCT scans were acquired in DICOM format using high-resolution tomography (PreXio, San Mateo, CA). The parameters for the 13-bit PreXion 3D Elite scanner included an isotropic voxel size of 0.100 mm, a field of view (FOV) measuring 52 mm × 56.00 mm (height by diameter), exposures lasting 33.5 s with 512 exposures per capture, X-ray output set at 90 kVp, a current of 4 mA, a focal spot measuring 0.20 mm × 0.20 mm, and a total beam filtration of > 2.5 mm Al. Subsequently, image capture of the bases and volume reconstruction used the PreXion 3D Elite. The DICOM files were post-processed using the following software packages: e-Vol DX 2.0 (CDT Software, São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil; https://cdtsoftware.com.br/index.php/produtos/e-vol-viewer). These software packages ran on a desktop computer equipped with Windows 10 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), featuring a 4.1-GHz i7-8750 processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA), and an 8-GB NVIDIA GTX 1070 graphics card (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA). All the images were displayed and analyzed on a 27-inch P2719H monitor with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels (DELL, Eldorado do Sul, Brazil).

Imaging methods (application of the artifact suppression and color map algorithms, together with the dynamic navigation strategy)

Two examiners (a radiologist and an endodontist), each with over 15 years of experience and expertise in using the e-Vol DX CBCT software, evaluated the images to identify any separated instruments. They were not involved in the preparation or incorporation of the separated instrument fragments into the filling material.

The PRs of each root canal were initially analyzed individually at various angles (distoradial, mesioradial, orthoradial, and proximal directions). The examiners recorded their findings on the presence or absence of separated instrument fragments on an Excel spreadsheet for further statistical analysis. The same image analysis environment and computer monitor were used for both methods (PR and CBCT).

The separated instrument fragment from the root canal fillings could be identified with CBCT scans by exporting the DICOM files acquired from each scanner with their original resolution, bit depth, and orientation, and subsequently importing them into the e-Vol DX software. CBCT scans of the teeth were reconstructed using a display voxel thickness of 0.1 mm. All the CBCT images followed the same positioning sequence. Each specimen was isolated from those acquired by using the “cut” tool, and then tilted in the three anatomical orientation planes (axial, coronal, and sagittal) so that the cut surface (slice) was parallel to the ground, so oriented to correct the Parallax bug. All images obtained were viewed and analyzed using the same monitor described previously.

After positioning the tooth correctly for analysis, the tool developed with the color map was applied. This tool used in regular mode displays gray shade images in various colors to represent the signal of the high density of both the instrument fragment (molecular weight) and the root-canal-filled obturating material, now interpreted by the software. The obturating material and the instrument fragment in the root canal, appearing as white or hyperdense on the color map, are predominantly represented by red. The metal contrast artifact produced by the obturating material, and the high-density endodontic instrument fragment causes the blooming to increase the volume of the material body and make it expand in all directions. In turn, this makes the material whiter and more voluminous. Subsequently, the application of the color map makes the material turn red. All initially red images are then subjected to successive tests using the developed algorithm, called blooming artifact reduction (BAR), and blooming is verified at different intensities of the algorithm (BAR 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4). Each intensity level involves unique adjustments of brightness, contrast, enhancement, and dynamic range. In the present study, the final validation included an examination of the grayscale image to visually confirm the contour of the object without the invasion of the hyperdense image into adjacent structures. The algorithm was selected based on color reformatting, by ensuring that the peripheral area of the specimen under evaluation appeared in a color distinct from red. Following the initial evaluation, the BAR 0.5 algorithm was selected to analyze the instrument fragments embedded in the obturating materials of the root canals. Brightness, contrast, and enhancement levels were previously determined by the software (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5, Supplemental Video S1).

The effects of ray hardening and inherent radiation scattering in the CBCT scan acquisition, together with concomitant application of the artifact reduction algorithm and the color map algorithm, called for adopting an important strategy to establish an image navigation protocol of 0.1 × 0.1 mm in the axial, sagittal, and coronal sections from coronal to apical thirds (or from apical to coronal thirds). The separated instrument fragment can be identified in the color map as a larger expansion in red (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5). This map provides valuable information by showing dynamic visualization toward the point of expansion of the high-density object, hence suggesting a separated instrument fragment (Supplemental Video S1). The values indicating presence or absence of the separated instrument were computed by and recorded in Excel.

Statistical analysis

The Excel spreadsheet for statistical analysis (Excel 2022, v2405; Microsoft Corporation, Richmond, WA, USA) was used to record the data. All the data were first analyzed descriptively, and then classified with a qualitative dichotomous variable (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows 20.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

The chi-square test was applied to compare the presence or absence of separated instruments shown on PRs versus CBCT images. Bonferroni correction addressed multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. The kappa values were used to assess intraexaminer variability.

Results

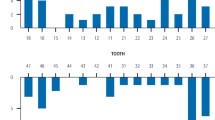

The kappa values for intraexaminer agreement were 0.86 and 0.96 for PR and CBCT images, respectively. Both kappa values corresponded to very good agreement. The presence or absence of separated instruments was evaluated in 1456 image views. Overall, CBCT was significantly superior to the PR (P < 0.001) for detecting separated instruments (Table 1). Moreover, CBCT tended not to be influenced by the endodontic sealer, image view or root canal (P > 0.05) (Table 2). On the other hand, PR revealed to be influenced by image view and root canal (P < 0.05). The lowest frequency of fractured instrument detection was on orthoradial view (n = 2; 1.9%) and when the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual root canals were overlapping (n = 2; 1.9%) (Table 3).

Discussion

The combined management of CBCT DICOMs, using post-processing software, together with tools that include artifact suppression algorithms (BAR 0.5), color map algorithms, and a dynamic navigation strategy, successfully identified the presence of separated instrument fragments in all the root canal fillings, compared with PRs, regardless of the sealer material used, image view or root canal (Tables 1 and 2). PRs were influenced by image view, and root canal. The lowest frequency of fractured instrument detection on orthoradial view (n = 2; 1.9%) and when the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual root canals were overlapping (n = 2; 1.9%) (Table 3).

The e-Vol DX software was created to improve the quality of images obtained by CBCT34. One of the benefits of this software is its compatibility with all current CBCT scanners, and its ability to export data in DICOM format. Its brightness and contrast adjustments are more comprehensive, thus enabling more precise control over the DICOM dynamic range, compared with other software having more limited options. It also offers customized settings for slice thickness and sharpness, features often restricted in other applications. The software incorporates an advanced noise reduction algorithm to enhance image quality34. Based on the current literature, two previous studies25,26 have used only one of these algorithms successfully for artifact reduction (BAR) when analyzing intraradicular posts. The application of the BAR algorithm in the e-Vol DX software did not modify the dimensions of intracanal posts (such as anatomically customized prefabricated glass fiber posts, low-fusion alloy posts, and gold alloy posts) in CBCT scans, in comparison with the measurements taken on the original posts with a micrometer25. Additionally, the effectiveness of the PreXion3D® Image Analysis System and the e-Vol DX software in reducing blooming artifacts in intracanal posts were assessed using the PreXion 3D Elite and the Carestream 9000 C 3D scanners26. The results showed that using the e-Vol DX CBCT software and DICOM images from Carestream 9000 C 3D and PreXion 3D Elite scanners successfully decreased blooming artifacts in images of metal structures.

Root canal preparation involves the use of instruments and irrigation strategies to control endodontic inflammation or infection, and thus allow effective endodontic and coronal sealing. The impact of this operative process on the predictability of success is high5. An operative accident such as a separated instrument constitutes a risk factor for RCT failure, depending on the preoperative state of the pulpal and/or periapical condition1. Additionally, some characteristics of separated instruments can make it difficult to predict their removal or analyze the prognosis, such as the moment when the instrument became separated (start of, midway through, or after cleaning and shaping), the location of the fracture (cervical, middle or apical third), the type, length and size of the separated instrument fragment, and the anatomical complexity of the tooth (anterior teeth, premolars, molars; curved, straight, and flat canals). In this sense, an appropriate diagnosis after the instrument fracture occurs is essential to conduct new therapeutic strategic planning, since a decision must be made to avert hassles, including judicial lawsuits1,2,3,4,5.

The significant difference between the results of the present study and the controversial results of others27,28,29,30, which showed that PRs allowed better visualization of the fragments of separated instruments within the root canals, can probably be attributed to the methodology used, and their non-application of algorithms or navigation through images. Rosen et al.27 assessed the diagnostic accuracy of CBCT imaging and PRs in identifying retained separated instruments in the apical third of filled root canals. Sixty single-rooted human teeth were prepared to size #25 and allocated to either a group where a 2 mm segment of a #30 K-file (made of SS or NiTi) was separated at the apical third, or to a control group with no separated instrument. The root canals were filled either to the separated instrument or to the working length for teeth without an instrument, using gutta-percha with AH26 or Roth sealer. The teeth were placed in a jaw model mimicking bone density, and imaged using CBCT and PR. PR was found to be more effective than CBCT in detecting retained separated instruments in the apical third of single-rooted human teeth with filled canals. Ramos-Brito et al.28 compared the detection of separated instruments in root canals with and without filling using PRs from 3 digital systems and CBCT images with different resolutions. Thirty-one human molars (80 canals) were divided into the control group with no fillings, the fracture group without fillings but with fractured files, the fill group with fillings, and the fill/fracture group with fillings and fractured files. Digital radiographs were taken in the ortho-, mesio-, and distoradial directions using two semi-direct systems (VistaScan and Express) and one direct system. CBCT images were obtained with voxel sizes of 0.085 mm and 0.2 mm. The PRs were accurate in detecting separated instruments inside the root canal, regardless of whether or not it was filled. For this reason, the PR technique and the direct digital radiographic system were recommended as the primary choice. Therefore, in cases where there is a filling, the decision to perform a CBCT examination should be made carefully due to its low accuracy. Costa et al.29 examined the impact of the metal artifact reduction (MAR) tool on detecting fractured instruments in the root canals of extracted mandibular molars, with or without root canal fillings. The root canals of 31 mandibular molars were distributed into the control group (no root fillings), fracture group (no fillings, with fractured files), fill group (with root filling), and fill/fracture group (root filled, with fractured files). Separated instruments such as SS hand files, NiTi reciprocating files, and NiTi rotary files were used in the study. Each tooth was placed in a dry mandible for CBCT imaging using CBCT OP300 3D Maxio and Picasso Trio, with and without the MAR tool. The results showed that the MAR tool did not improve the detection of fractured endodontic instruments or reduce image noise in extracted mandibular molars. Therefore, the MAR tool is not recommended for evaluating separated instruments in mandibular molars with or without root fillings. Baratto-Filho et al.30 evaluated the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of both CBCT and digital periapical radiography (DPR) images in detecting separated instruments in filled root canals. The 108 root canals of 36 prepared and filled mandibular molars were examined. Of these, 84 were filled without any separated instruments, while 24 were filled with separated instruments (either SS hand files or reciprocating instruments). The different CBCT imaging protocols included those of the following instruments: i-CAT Classic (ICC) with 0.25-mm isotropic voxel size, i-CAT Next Generation (ICN) with 0.125-mm isotropic voxel size, and PreXion 3D (PXD) with 0.09-mm isotropic voxel size. Additionally, an exam was obtained with DPR using the parameters of 08 mA, 70 kVp, and 0.2 s of exposure time. Only nine instruments were identified in the DPR images (37.5%), while none were detected in the CBCT protocols. The type of separated instrument did not affect the ability to identify it. DPR had the highest accuracy and sensitivity rates of 83.3% and 37.5%, respectively, compared with the CBCT protocols. DPR was found to be the superior imaging technique for detecting separated instruments within root canals. However, most of the separated instruments were not detected in any of the imaging exams.

A distinguishing feature of this pioneering study was the joint application of the blooming artifact reduction and the color map algorithms, developed and incorporated into the post-processing software. Another strategy that also showed an impact on the results was dynamic navigation through CBCT scans. The existence of high-density materials (such as solid dental structures or metal objects) in the root canal, such as gutta-percha, root canal filling materials, or separated instrument fragments, can lead to the creation of metal artifacts16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. These artifacts have the potential of impacting the quality of the image, and potentially leading to diagnostic errors. Metal artifacts appear as distortions in CBCT images, alter the gray tones, and impair the accuracy of structures, ultimately diminishing image quality and hindering diagnosis. The beam hardening effect occurs when X-ray beams pass through high-density materials, causing beams to harden, scattering radiation and resulting in varied metal artifacts16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26.

The artifact suppression algorithm was developed as an additional tool in the e-Vol DX software34. When applied, it restores normal grayscale contrast in the image, and preserves clarity by reducing the white areas in the original image, thereby preventing metal material or root canal filling materials from creating artifacts. This tool, called blooming artifact reduction (BAR), allows adjustments to be made in brightness, contrast, enhancement, and dynamic range at four different intensities (BAR 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4). Final verification of the grayscale image confirms the visual delineation of the object without interference from the hyperdense image in adjacent structures. In this study, endodontically treated teeth were analyzed using BAR 0.5 settings. Additionally, a color map algorithm was integrated into this tool, and serves to reformulate colors based on the molecular weight of the separated instrument fragment, thereby ensuring that the peripheral area of the specimen retains a distinct color other than red. An important strategy when using artifact reduction algorithms is to establish an image navigation protocol in all planes to counter the effect of hardening of rays and inherent radiation scattering in acquiring the CBCT scan. The separated instrument fragment appears in the color map with a larger expansion in red to allow identification. Therefore, this map provides valuable information by showing dynamic visualization at the point of expansion of the high-density object, which indicates a separated instrument fragment34.

A crucial aspect that must be considered in using e-Vol DX software effectively is understanding the basic principles of image capture, which are similar to those used in traditional photographic cameras. The RAW (native) image format contains both detailed information on the captured object and a large number of pixels from the sensor. The e-Vol DX package includes various algorithms specifically designed to align with the principles of the RAW format, thus helping to maintain the quality of the captured image, and potentially recovering areas that were either underexposed or overexposed. These filters prevent loss of image quality, while improving the saturation and brightness of specific areas, especially in bright regions that may take up a significant amount of file space34.

The software not only applies artifact-reducing and color-mapping algorithms, but also features dynamic navigation of 0.1 × 0.1 mm in all thirds of the image, as opposed to static image template visualization, thus providing a greater amount of information. Other factors that should be taken into consideration include the required widening of the root canal. In our study, the canals were widened by 400 μm, and the instruments were incorporated into the main gutta-percha cone #40.04 and filled using the lateral condensation technique. The 2 mm separated instrument fragments were accommodated in the apical region 5 mm apically from the preparation. This level of widening and the different positions of the instrument fragments were challenging for the evaluators to consider. These factors may explain the contradictory results, which attributed better performance to PR27,28,29,30 than in our results, in which CBCT scans detected the fractured instruments better.

The variables examined (image view and root canal) affected the results only in the PR. The lowest frequency in detecting separated instruments occurred in the orthoradial view (n = 2; 1.9%), and when the mesiobuccal and mesiolingual root canals overlapped (n = 2; 1.9%). Clark’s technique allows the separation of three-dimensional-structured images viewed two-dimensionally in PR, thus facilitating the observation of overlapping objects. Although this technique was implemented in this study, only 32.3% of the cases using PR were able to identify separated instrument fragments.

The selection of the sealer materials analyzed was based on their high usage in clinical practice, and more specifically, due to the presence of chemical components in their formulations that may induce metallic artifacts in CBCT scans20. The chemical components of the tested sealers that may affect the quality of imaging examinations for each material include: Sealapex (containing calcium oxide), EndoFill (based on zinc oxide and eugenol), AH Plus (an epoxy resin containing zirconia and tungsten), and BioC Sealer (a cement composed of various elements, including tricalcium silicate, dicalcium silicate, and tricalcium aluminate)35.

A limitation of this new method for detecting separated instruments in the root canal based on in post-processing CBCT software is related to the learning curve of the professional. The adoption of new technologies requires familiarity and experience, which can affect diagnostic accuracy, particularly during the early stages of implementation. Although the software is intuitive, user adaptation may vary, necessitating continuous training and an adjustment period to ensure effectiveness. Inadequate interaction with the technology in complex clinical settings may compromise the accuracy of the results.

The clinical relevance of this study lies in its application of biological responses to routine practice in diagnosing separated instruments using computational analysis and artificial intelligence in advanced CBCT software. The algorithms in the CBCT software can process raw data to create images that minimize metal artifacts, highlight high-density materials with color maps, and allow multidimensional navigation. CBCT imaging is crucial for diagnosis, decision-making, planning, prognosis, and management of root canal treatments. The reliability and validity of CBCT have made it a highly valuable imaging tool in clinical practice.

Conclusions

The artifact suppression and color map algorithm of post-processing CBCT software, combined with dynamic navigation, effectively identified separated instrument fragments in all the root canal fillings, regardless of the filling material, image view, or root canal. Only 32.3% of the filling images viewed by PR were able to detect separated instrument fragments. This methodology seems to be useful in the resolution of the problem of viewing separated instruments with CBCT post-processing software.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Estrela, C. et al. Common operative procedural errors and clinical factors associated with root canal treatment. Braz. Dent. J. 28, 179–190 (2017).

Hülsmann, M. & Schinkel, I. Influence of several factors on the success or failure of removal of fractured instruments from the root canal. Endod. Dent. Traumatol. 15, 252–258 (1999).

Spili, P., Parashos, P. & Messer, H. H. The impact of instrument fracture on outcome of endodontic treatment. J. Endod. 31, 845–850 (2005).

McGuigan, M. B., Louca, C. & Duncan, H. F. The impact of fractured endodontic instruments on treatment outcome. Br. Dent. J. 214, 285–289 (2013).

Estrela, C. et al. Characterization of successful root canal treatment. Braz. Dent. J. 25, 3–11 (2014).

Arias, A. & Peters, O. A. Present status and future directions: Canal shaping. Int. Endod. J. 55, 637–655 (2022).

Terauchi, Y., Ali, W. T. & Abielhassan, M. M. Present status and future directions: Removal of fractured instruments. Int. Endod. J. 55, 685–709 (2022).

Madarati, A. A., Hunter, M. J. & Dummer, P. M. Management of intracanal separated instruments. J. Endod. 39, 569–581 (2013).

Bender, I. B. Factors influencing the radiographic appearance of bony lesions. J. Endod. 8, 161–170 (2013).

Estrela, C., Bueno, M. R., Leles, C. R., Azevedo, B. C. & Azevedo, J. R. Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography and panoramic and periapical radiography for detection of apical periodontitis. J. Endod. 34, 273–279 (2008).

Arai, Y., Tammisalo, E., Iwai, K., Hashimoto, K. & Shinoda, K. Development of a compact computed tomographic apparatus for dental use. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 28, 245–248 (1999).

Benjamin, G., Ather, A., Bueno, M. R., Estrela, C. & Diogenes, A. Preserving the neurovascular bundle in targeted endodontic microsurgery: A case series. J. Endod. 47, 509–519 (2021).

Estrela, C., Bueno, M. R., Azevedo, B. C., Azevedo, J. R. & Pécora, J. D. A new periapical index based on cone beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 34, 1325–1331 (2008).

Estrela, C. et al. Method to evaluate inflammatory root resorption by using cone beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 35, 1491–1497 (2009).

Estrela, C. R. A. et al. Frequency and risk factors of maxillary sinusitis of endodontic origin evaluated by a dynamic navigation and a new filter of cone-beam computed tomography. J. Endod. 48, 1263–1272 (2022).

Barrett, J. F. & Keat, N. Artifacts in CT: Recognition and avoidance. Radiographics 24, 1679–1691 (2004).

Katsumata, A. et al. Image artifact in dental cone-beam CT. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 101, 652–657 (2006).

Schulze, R. et al. Artefacts in CBCT: A review. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 40, 265–273 (2011).

Bechara, B. B., Moore, W. S., McMahan, C. A. & Noujeim, M. Metal artefact reduction with cone beam CT: An in vitro study. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 41, 248–253 (2012).

Decurcio, D. A. et al. Effect of root canal filling materials on dimensions of cone-beam computed tomography images. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 20, 260–267 (2012).

Brito-Júnior, M., Santos, L. A., Faria-e-Silva, A. L., Pereira, R. D. & Sousa-Neto, M. D. Ex vivo evaluation of artifacts mimicking fracture lines on cone-beam computed tomography produced by different root canal sealers. Int. Endod. J. 47, 26–31 (2014).

Bueno, M. R., Estrela, C., Figueiredo, J. A. P. & Azevedo, B. C. Map-reading strategy to diagnose root perforations near metallic intracanal posts by using cone beam computed tomography. J. Endod.. 37, 85–90 (2011).

Vasconcelos, K. F. et al. Artefact expression associated with several cone-beam computed tomographic machines when imaging root filled teeth. Int. Endod. J. 48, 994–1000 (2015).

Celikten, B. et al. Comparative evaluation of cone beam CT and micro-CT on blooming artifacts in human teeth filled with bioceramic sealers. Clin. Oral Investig.. 23, 3267–3273 (2019).

Estrela, C. et al. Potential of a new cone-beam CT software for blooming artifact reduction. Braz. Dent. J. 31, 582–588 (2020).

Rabelo, L. E. G. et al. Blooming artifact reduction using different cone-beam computed tomography software to analyze endodontically treated teeth with intracanal posts. Comput. Biol. Med. 136, 104679 (2021).

Rosen, E. et al. A comparison of cone-beam computed tomography with periapical radiography in the detection of separated instruments retained in the apical third of root canal-filled teeth. J. Endod.. 42, 1035–1039 (2016).

Ramo-Brito, A. C. et al. Detection of fractured endodontic instruments in root canals: Comparison between different digital radiography systems and cone-beam computed tomography. J. Endod.. 43, 544–549 (2017).

Costa, E. D. et al. Use of the metal artefact reduction tool in the identification of fractured endodontic instruments in cone-beam computed tomography. Int. Endod. J. 53, 506–512 (2020).

Baratto-Filho, F. et al. Cone-beam computed tomography detection of separated endodontic instruments. J. Endod.. 46, 1776–1781 (2020).

Panitvisai, P., Parunnit, P., Sathorn, C. & Messer, H. H. Impact of a retained instrument on treatment outcome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Endod.. 36, 775–780 (2010).

Venskutonis, T., Plotino, G., Juodzbalys, G. & Mickevičienė, L. The importance of cone-beam computed tomography in the management of endodontic problems: A review of the literature. J. Endod.. 40, 1895–1901 (2014).

Sousa, V. C. et al. Evaluation in the danger zone of mandibular molars after root canal preparation using novel CBCT software. Braz. Oral Res. 36, e038 (2022).

Bueno, M. R., Estrela, C., Azevedo, B. C. & Diogenes, A. Development of a new cone-beam computed tomography software for endodontic diagnosis. Braz. Dent. J. 29, 517–529 (2018).

Sampaio, F. C. et al. Chemical elements characterization of root canal sealers using scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray analysis. Oral Health Dent. Manag.. 13, 27–34 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This study received the partial support of grants provided by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq grants 308632/2021-4 to C.E.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R.A.E., M.R.B., and C.E. conceptualized and designed the study. L.R.A.E., M.R.B., B.C.A., V.C.S., O.A.G., and C.E. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data. L.R.A.E., M.R.B., B.C.A., O.A.G., and C.E. drafted the manuscript. L.R.A.E., M.R.B., B.C.A., V.C.S., O.A.G., and C.E. provided resources. L.R.A.E., M.R.B., and C.E. revised the manuscript and provided supervision and project administration. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Estrela, L.R.d.A., Bueno, M.R., Azevedo, B.C. et al. A novel methodology for detecting separated endodontic instruments using a combination of algorithms in post-processing CBCT software. Sci Rep 15, 6088 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90652-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90652-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Photon-counting CT outperforms dental CBCT in detecting small accessory canals in root-filled teeth in a phantom study

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Expert consensus on management of instrument separation in root canal therapy

International Journal of Oral Science (2025)