Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia often treated with cryoballoon ablation. The impact of Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MASLD), a condition newly defined by a fatty liver index ≥ 60, on AF recurrence post-ablation is unclear. We analyzed 303 patients undergoing cryoballoon ablation for AF. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the relationship between MASLD and AF recurrence. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was present in 61.1% of patients and 63% were male. Among the patients, 23.4% had MASLD. These patients exhibited larger left atrial diameter and left ventricular end-diastolic dimension. During a median follow-up of 14 months, AF recurrence was more frequent in MASLD patients (45.1% vs. 20.7%). MASLD independently predicted AF recurrence (HR, 2.24 [95% CI 1.35–3.74], P = 0.002), alongside persistent AF, longer AF duration, and larger left atrial diameter. MASLD consistently demonstrated a significant association with an increased risk of AF recurrence in both paroxysmal (HR, 2.38 [95% CI, 1.08–5.23], P = 0.031) and persistent AF (HR, 2.55 [95% CI, 1.23–5.26], P = 0.011). MASLD significantly increases the risk of AF recurrence after cryoballoon ablation, highlighting the importance of supporting targeted interventions of MASLD in the periprocedural management of AF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common cardiac arrhythmias and significantly increases the risk of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality1. Catheter ablation has emerged as an effective treatment for patients with AF, particularly when antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) are insufficient in controlling arrhythmia recurrence2. Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) is a fundamental strategy in most AF ablation procedures. Cryoballoon ablation has been shown to be as effective as radiofrequency ablation in achieving PVI, offering benefits such as reduced procedure time, reproducibility, and less dependence on operator skill3. Nevertheless, a significant rate of AF recurrence post-ablation has been observed, affecting 20–50% of patients4. AADs, while used, can pose the risk of significant drug-drug interactions and serious side effects, and their use is not strongly recommended in guidelines. Currently recognized risk factors cannot fully explain the risk of AF recurrence5, and therefore, identifying novel triggers of AF recurrence is crucial.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) stands as the most prevalent chronic liver ailment worldwide, affecting up to 25% of the population6,7. It is a primary driver of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and exerts notable impacts on extrahepatic organs. NAFLD elevates the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease8. A growing body of observational studies indicates a robust association between NAFLD and heightened risk of AF9,10,11,12,13,14. Furthermore, recent findings suggest that NAFLD may correlate with a notable increase in arrhythmia recurrence rates post AF ablation7, as well as significantly elevated odds of in-hospital mortality, and readmissions at 30 and 90 days15. No studies have explored the association between fatty liver disease and AF recurrence post-cryoballoon ablation.

While the term “nonalcoholic” is commonly used, it fails to accurately depict the true nature of the disease16. In 2023, three large multinational liver associations proposed “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease” (MASLD) as a more fitting term to replace NAFLD17. Unlike NAFLD, MASLD acknowledges varying levels of alcohol consumption and underscores the role of metabolic abnormalities in liver conditions17,18. Evidence regarding the link between MASLD and cardiovascular outcomes is limited. Few studies, including ours19, have indicated a higher risk of cardiovascular disease19,20 and cardiac arrhythmias19,21 associated with MASLD. However, no research has examined the relationship between MASLD and AF recurrence post-cryoballoon ablation. This study seeks to investigate the impact of MASLD on arrhythmia recurrence rates following AF cryoballoon ablation.

Methods

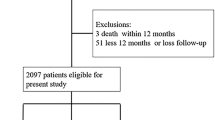

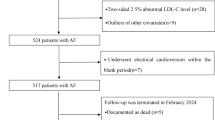

Study population

This study population consisted of consecutive patients who underwent initial cryoballoon ablation for atrial fibrillation at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital between September 1 2020 and September 30 2023. All patients were prospectively followed up for a minimum of 1 year. Exclusions comprised patients aged ≤ 18 years, individuals with moderate-to-severe valve stenosis or severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, those with a history of prior AF catheter ablation, individuals with overt hyperthyroidism, and those presenting with contraindications for PVI (e.g., acute thrombus formation or bleeding)22. Patients who lost to follow-up were also excluded from the analysis. Patients were further identified and divided into 2 groups based on the diagnosis of MASLD at baseline. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board and was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Diagnosis of MASLD

Hepatic steatosis was assessed using the fatty liver index (FLI), based on body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, triglycerides, and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT). FLI has demonstrated good reliability as an alternative to imaging techniques such as ultrasonography and transient elastography, showing a good diagnostic performance with an area under the receiver operator curve (AUROC) of 0.8523. An FLI ≥ 60 indicated hepatic steatosis23. MASLD was defined as the presence of hepatic steatosis along with ≥ 1 pre-defined cardiometabolic risk factor, such as overweight or abnormalities in glucose, blood pressure, lipids, or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, excluding secondary liver steatosis causes24.

Preoperative management

All patients underwent uninterrupted anticoagulation therapy for a minimum of 4 weeks prior to cryoballoon ablation, with non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) or warfarin with a target international normalized ratio between 2.0 and 3.0. Antiarrhythmic therapy, excluding β-blockers, was ceased 4 to 5 half-lives before the PVI procedure to reduce the potential influence of antiarrhythmic medications on the ablation procedure outcomes. Cardiac structure and function were assessed using routine transthoracic echocardiography, which included evaluating parameters such as left atrial diameter (LAD) and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Transesophageal echocardiography was conducted before PVI to exclude intracavitary thrombi. Baseline fasting blood samples were collected from all patients upon hospitalization.

Cryoballoon ablation

The ablations were carried out under conscious sedation, using midazolam and fentanyl as needed. PVI was performed on all patients using a cryoballoon. This procedure was carried out by one of three experienced electrophysiologists (Xinlin Zhang, Zheng Chen, and Wei Xu), each having completed over 100 cryoballoon PVI procedures. The process began with transseptal catheterization, followed by intravenous heparin administration to maintain an activated clotting time of at least 300 s. The cryoballoon catheter was introduced into the left atrium via a 12-Fr steerable sheath (FlexCath Advance, Medtronic, Inc.). Pulmonary veins (PVs) mapping was conducted using an inner lumen mapping catheter (Achieve, Medtronic, Inc.). For each PV antrum, a 28-mm cryoballoon catheter (Arctic Front Advance, Medtronic) was inflated and positioned. To enhance pulmonary vein signal detection, the mapping catheter was positioned close to the balloon’s tip. The quality of PV occlusion was evaluated by the operator on a scale of 1–4, where 4 indicates a complete occlusion with no visible contrast leak into the left atrium. Optimal vessel occlusion was confirmed through radiocontrast dye injection. The number and duration of cryoapplications for each PV ablation were at the physician’s discretion, typically targeting 4 to 5 min based on the time to isolation (TTI). TTI is defined as the duration from the start of freezing to the disappearance of the last recorded PV potentials. When ablating right-sided pulmonary veins, a steerable quadripolar catheter was placed in the superior vena cava to monitor phrenic nerve activity.

Postoperative management and follow-pp

Post-ablation, anticoagulation therapy was maintained for at least 3 months, with continued administration thereafter determined by each patient’s CHA2DS2-VASC score. An AAD was usually prescribed during the initial 3-month blanking period, after which its discontinuation was strongly advised.

Patients were prospectively scheduled for follow-up visits at our outpatient clinic at 3-, 6-, and 12-month post-ablation, and then every 12 months or whenever symptoms reappeared. Rhythm monitoring during these visits included clinical assessments for AF recurrence, routine electrocardiograms, and Holter monitoring. In cases where patients experienced palpitations, an ECG or Holter was performed to detect any arrhythmic recurrence. AF recurrence was defined as any AF, atrial flutter (AFL) or atrial tachycardia (AT) episode lasting at least 30 s, irrespective of AAD use. Clinical recurrence was identified as any electrocardiographic evidence of AF after the 3-month blanking period.

Statistical analysis

We presented categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies, while continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Baseline characteristic comparisons employed independent Student’s t-test or χ2 tests, where appropriate. To illustrate freedom from AF, we estimated unadjusted survival curves using the Kaplan-Meier method, comparing groups with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models assessed the association between baseline MASLD status and AF recurrence, including potential confounders identified in univariate analyses (with P < 0.10) as baseline patient characteristics, as well as previously identified predictors from the literature. Certain covariates such as waist circumference, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia were not adjusted for, as they were already incorporated into the definitions of MAFLD and MASLD to avoid overadjustment25,26. Subgroup analyses were performed in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF. We set the threshold for statistical significance at P ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 10.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 303 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing cryoballoon ablation were included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of the MASLD and non-MASLD cohorts are shown in Table 1. In the study cohort, 63% were male, with a mean age of 60.8 ± 9.66 years. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation was present in 61.1% of patients. The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 1.79 ± 1.37, with no significant difference between groups (P = 0.843). Mean BMI was 25.0 ± 3.2 kg/m2, and AF duration was 24.5 ± 37.5 months. The mean LAD measured 40.6 ± 4.06 mm, and LVEF was 58.64 ± 4.31%.

All cryoballoon ablation procedures employed a 28-millimeter balloon, successfully isolating all PVs. Mean procedure and fluoroscopy times were 102.1 ± 31.3 and 23.2 ± 13.1 min, respectively. TTI for left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV), left inferior pulmonary vein (LIPV), right inferior pulmonary vein (RIPV), and right superior pulmonary vein (RSPV) averaged 41.39 ± 10.21, 30.37 ± 15.95, 43.14 ± 23.75, and 35.41 ± 18.26 s, respectively. Lowest temperatures achieved during ablation were − 51.15 ± 4.68 °C for LSPV, − 46.65 ± 4.75 °C for LIPV, − 49.56 ± 5.85 °C for RIPV, and − 53.45 ± 4.01 °C for RSPV. Ablation of the right middle pulmonary vein (RMPV) was performed in 17 patients (5.6%) (Table 2).

Baseline characteristics between MASLD and non-MASLD groups

The diagnosis of MASLD was established based on FLI ≥ 60 in 71 individuals (23.4%). Patients in the MASLD group tended to be younger (57.7 vs. 61.8 years, P = 0.002), with a higher prevalence of smoking (25 [35.2%] vs. 48 [20.7%], P = 0.016) and alcohol consumption (23 [32.4%] vs. 31 [13.4%], P < 0.001). Similarly, coronary artery disease (15 [21.1%] vs. 21 [9.1%], P = 0.011), heart failure (19 [26.8%] vs. 32 [13.8%], P = 0.017), and dyslipidemia (27 [38%] vs. 43 [18.5%], P = 0.001) were more commonly diagnosed in those with MASLD (Table 1).

Mean TSH levels (2.28 vs. 2.65 mIU/L, P = 0.051) and hemoglobin levels (145.1 vs. 139.3 g/L, P = 0.004) were higher in patients with MASLD. Among patients with MASLD, median LAD (42.3 vs. 40.1 mm, P < 0.001) and LVDD (51.04 vs. 49.04 mm, P < 0.001), IVSTD (9.6 vs. 8.78 mm, P < 0.001), and LVPWTD (9.43 vs. 8.65 mm, P < 0.001) were larger compared to those in the non-MASLD cohort. Mean LVEF (57.3 vs. 59.04%, P = 0.013) was lower in those with MASLD compared to those without. The characteristics of cryoablation procedures were similar between the MASLD and non-MASLD groups (Table 2).

Recurrence

During a median follow-up of 14 months, recurrent arrhythmia was observed in 32 (45.1%) patients with MASLD compared with 48 (20.7%) without MASLD. In univariate analysis, a higher recurrence rate was observed in patients with MASLD, male, and those with persistent AF, a larger LAD, a longer AF duration, a lower LVEF, a higher hemoglobin, and in patients with an alcohol habit. After multivariable adjustment, MASLD remained independently associated with a higher risk of AF recurrence (hazard ratio [HR], 2.24 [95% CI, 1.35–3.74], P = 0.002) (Fig. 1). Persistent AF (HR, 1.87 [95% CI, 1.16–3.02], P = 0.01), a longer AF duration (HR, 1.01 [95% CI, 1.01–1.02], P < 0.001), and a larger LAD (HR, 1.07 [95% CI, 1.00–1.14], P = 0.046) were identified as significant predictors of AF recurrence (Table 3).

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was conducted to identify independent variables associated with AF recurrence in patients with paroxysmal and persistent AF. Notably, MASLD consistently demonstrated a significant association with an increased risk of AF recurrence in both paroxysmal (HR, 2.38 [95% CI, 1.08–5.23], P = 0.031) and persistent AF (HR, 2.55 [95% CI, 1.23–5.26], P = 0.011) (Table 4). Moreover, sensitivity analysis excluding individuals with alcohol consumption habits yielded consistent results (HR, 2.25 [95% CI, 1.35–3.78], P = 0.002) (Fig. S1).

Discussion

In this study, we further highlighted that MASLD, proposed as a replacement for NAFLD, independently predicts a heightened risk of AF recurrence following cryoballoon ablation, even after adjusting for traditional risk factors such as age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, and BMI. Our investigation marks the first endeavor to explore the link between liver disease and AF recurrence post-catheter ablation, within the context of transitioning from NAFLD to the etiology-based definition of MASLD. Importantly, our findings confirm the consistent prognostic significance of MASLD across patients with both paroxysmal and persistent AF, providing compelling evidence for targeted interventions in the periprocedural management of AF.

Growing evidence implicates metabolic disturbances in the pathogenesis of AF, driving structural and electrophysiological remodeling27. Prior studies have underscored the impact of metabolic disorders, such as diabetes mellitus and obesity, on AF risk. Diabetes elevates the risk of AF by up to 34%29, with higher baseline glycated hemoglobin associated with increased rates of arrhythmia recurrence post-AF ablation, irrespective of diabetes status, as revealed in our previous study22. Oral diabetes medications, including sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, have demonstrated efficacy in reducing AF risk and recurrence post-ablation28,29. Similarly, obesity has emerged as a modifiable risk factor for AF, with weight loss linked to reduced AF incidence and recurrence post-ablation7,30. The ABC pathway outlined in recent AF guidelines emphasizes optimization of cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities, with comprehensive interventions targeting metabolic conditions yielding reductions in AF burden and recurrence after ablation31.The relationship between NAFLD and diabetes is intricate and bidirectional. Previous investigations have highlighted a robust association between NAFLD and an increased incidence of AF, independent of conventional cardiometabolic comorbidities32,33. Several studies have explored the impact of NAFLD, and its associated advanced liver fibrosis, on AF recurrence following radiofrequency (RF) catheter ablation. In a retrospective analysis involving 267 patients undergoing ablation, Donnellan et al. found that NAFLD independently correlated with heightened rates of arrhythmia recurrence (HR 3.01, P < 0.0001)7. Similarly, Agarwal et al. utilizing the National Readmissions Database and a larger cohort comprising 709 patients with NAFLD and approximately 50,000 without, corroborated that NAFLD presence was associated with significantly increased odds of in-hospital mortality and 90-day all-cause readmissions15. Additionally, two other retrospective cohort studies, albeit with modest sample sizes, demonstrated a positive correlation between higher liver scores and increased AF recurrence burden6,11. Liver fibrosis remains an important driver of systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and atrial remodeling, contributing to AF recurrence34,35. Interestingly, Ballestri et al. suggested these patients, given that both NAFLD and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are independently associated with AF and venous thromboembolism, may benefit from anticoagulation therapy as potential candidates36. Based on the potential inclusion bias or disparities in population distribution, the limited number of high-risk liver fibrosis cases in this study (Table S1) might have influenced the results, leading to the absence of significant group differences or associations with AF recurrence (Figs. S2 and S3).

In contrast to the previous definitions of NAFLD/metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), MASLD provides a nuanced approach to characterizing fatty liver disease by integrating various metabolic abnormalities. This not only distinguishes liver steatosis associated with metabolic dysfunction but also has important implications for AF recurrence risk stratification. Despite this, few studies have investigated the impact of MASLD on the risk of cardiovascular diseases. In our previous work, we demonstrated that MASLD was associated with a heightened risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR 1.3, P < 0.0001), heart failure (HR 1.7, P < 0.0001), and atrial fibrillation (HR 1.27, P < 0.0001)19, findings consistent with other research20,21. Notably, to our knowledge, there is a paucity of studies investigating the association between MASLD and AF recurrence following catheter ablation, and no study investigated the association between any liver disease with recurrence following cryoballoon ablation. In this study, we validated the significant prognostic impact of MASLD on AF recurrence following cryoballoon ablation, regardless of AF status. With new AF catheter ablation techniques like RF37 and pulsed field ablation (PFA)38,39, our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence identifying MASLD as a modifiable risk factor for AF recurrence. Intensive management of this metabolic syndrome prior to and post-AF ablation, incorporating newly discovered medications such as oral, liver-directed, thyroid hormone receptor beta–selective agonist resmetirom40, Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) analogue pegozafermin41, novel agonists of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors42,43, or lifestyle interventions, may offer valuable ways for reducing the risk of AF recurrence.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study should be acknowledged. Firstly, hepatic steatosis was defined using the FLI rather than liver biopsy or imaging. Nonetheless, the FLI has shown strong correlation with ultrasound diagnosis of NAFLD in several studies44,45. Only a limited amount of imaging data was available for the cohort, which was insufficient for meaningful analysis in this study. Secondly, despite controlling for a wide range of confounders, potential residual confounding may persist. Thirdly, the assessment of MASLD was conducted only at baseline, with a lack of data on exposure durations and any changes during the follow-up period. Fourthly, the observational natural of our study precludes establishment of causality, and further study are needed to determine whether modulating MASLD could improve outcomes after ablation.

Conclusions

Our study showed that MASLD predicted an increased risk of AF recurrence after cryoballoon ablation, independent of whether patients have paroxysmal or persistent AF. Further research is necessary to support targeted interventions of MASLD in the peri-procedural management of AF.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Nattel, S. et al. Early management of atrial fibrillation to prevent cardiovascular complications. Eur. Heart J. 35, 1448–1456. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu028 (2014).

Hindricks, G. et al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 42, 373–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612 (2021).

Providencia, R. et al. Results from a multicentre comparison of cryoballoon vs. radiofrequency ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: is cryoablation more reproducible? Europace 19, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw080 (2017).

Turagam, M. K. et al. Assessment of Catheter ablation or antiarrhythmic drugs for first-line therapy of Atrial Fibrillation: a Meta-analysis of Randomized clinical trials. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 697–705. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0852 (2021).

Andrade, J., Khairy, P., Dobrev, D. & Nattel, S. The clinical profile and pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation: relationships among clinical features, epidemiology, and mechanisms. Circ. Res. 114, 1453–1468. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211 (2014).

Wang, Z. et al. Impact of advanced liver fibrosis on atrial fibrillation recurrence after ablation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 960259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.960259 (2022).

Donnellan, E. et al. Impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on Arrhythmia Recurrence following atrial fibrillation ablation. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 6, 1278–1287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2020.05.023 (2020).

Powell, E. E., Wong, V. W. S. & Rinella, M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet 397, 2212–2224. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32511-3 (2021).

Ohno, R. et al. Association of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease with risk of HF and AF. JACC Asia. 3, 908–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacasi.2023.08.003 (2023).

Carbone, R. G. & Puppo, F. Atrial fibrillation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 378, 879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.02.033 (2023).

Decoin, R. et al. High liver fibrosis scores in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease patients are associated with adverse atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation recurrence following catheter ablation. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 13, 957245. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.957245 (2022).

Huang, W. A., Dunipace, E. A., Sorg, J. M. & Vaseghi, M. Liver disease as a predictor of New-Onset atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e008703. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.008703 (2018).

Pastori, D. et al. Prevalence and impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Atrial Fibrillation. Mayo Clin. Proc. 95, 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.08.027 (2020).

Wijarnpreecha, K., Boonpheng, B., Thongprayoon, C., Jaruvongvanich, V. & Ungprasert, P. The association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 41, 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2017.08.001 (2017).

Agarwal, S. et al. Outcomes and readmissions in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 21, 502–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.12.019 (2024).

Wong, V. W., Ekstedt, M., Wong, G. L. & Hagstrom, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 79, 842–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036 (2023).

Rinella, M. E. et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 79, 1542–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.06.003 (2023).

Hirata, A. & Okamura, T. New insights into the relation between metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease. JACC Asia 3, 922–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacasi.2023.08.013 (2023).

Zhang, X. L., Bao, X. & Xu, B. Association of MASLD and MAFLD with cardiovascular and mortality outcomes: a prospective study of the UK biobank cohort. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 1729 (2024).

Lee, H. H. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and risk of cardiovascular disease. Gut 73, 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2023-331003 (2024).

Simon, T. G. et al. Incident cardiac arrhythmias associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a nationwide histology cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 343. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02070-5 (2023).

Chen, Z., Zhang, R., Zhang, X. & Xu, W. Association between baseline glycated hemoglobin level and atrial fibrillation recurrence following cryoballoon ablation among patients with and without diabetes. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 24, 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-024-03784-4 (2024).

European Association for the Study of the, L. European Association for the Study of, D. & European Association for the study of, O. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 64, 1388–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004 (2016).

Bedogni, G. et al. The fatty liver index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol. 6, 896. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-6-33 (2006).

Zhao, Q. & Deng, Y. Comparison of mortality outcomes in individuals with MASLD and/or MAFLD. J. Hepatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.08.003 (2023).

Lee, H., Lee, Y. H., Kim, S. U. & Kim, H. C. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and incident cardiovascular disease risk: a Nationwide Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19(e2110), 2138–2147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.12.022 (2021).

Bode, D., Pronto, J. R. D., Schiattarella, G. G. & Voigt, N. Metabolic remodelling in atrial fibrillation: manifestations, mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-024-01038-6 (2024).

Zelniker, T. A. et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on atrial fibrillation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial. Circulation 141, 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044183 (2020).

Abu-Qaoud, M. R. et al. Impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on AF recurrence after catheter ablation in patients with type 2 diabetes. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 9, 2109–2118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacep.2023.06.008 (2023).

Powell-Wiley, T. M. et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, e984–e1010. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973 (2021).

Romiti, G. F. et al. Clinical complexity and impact of the ABC (Atrial fibrillation Better Care) pathway in patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the ESC-EHRA EURObservational Research Programme in AF General Long-Term Registry. BMC Med. 20, 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02526-7 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging driver of Cardiac Arrhythmia. Circ. Res. 128, 1747–1765. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319059 (2021).

Mantovani, A. et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of atrial fibrillation in adult individuals: an updated meta-analysis. Liver Int. 39, 758–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.14044 (2019).

Park, H. E., Lee, H., Choi, S. Y., Kim, H. S. & Chung, G. E. The risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and a high hepatic fibrosis index. Sci. Rep. 10, 5023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61750-4 (2020).

van Kleef, L. A. et al. Liver stiffness not fatty liver disease is associated with atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. J. Hepatol. 77, 931–938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.05.030 (2022).

Ballestri, S. et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with liver disease in the era of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease global epidemic: a narrative review. Adv. Ther. 37, 1910–1932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01307-z (2020).

Parameswaran, R., Al-Kaisey, A. M. & Kalman, J. M. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: current indications and evolving technologies. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 18, 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-00451-x (2021).

Reddy, V. Y. et al. Pulsed field or conventional thermal ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 389, 1660–1671. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2307291 (2023).

Verma, A. et al. Pulsed field ablation for the treatment of atrial fibrillation: PULSED AF pivotal trial. Circulation 147, 1422–1432. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.063988 (2023).

Harrison, S. A. et al. A phase 3, randomized, controlled trial of resmetirom in NASH with liver fibrosis. N Engl. J. Med. 390, 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2309000 (2024).

Loomba, R. et al. Controlled trial of the FGF21 Analogue Pegozafermin in NASH. N Engl. J. Med. 389, 998–1008. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2304286 (2023). Randomized.

Loomba, R. et al. Tirzepatide for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis with liver fibrosi. N Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2401943 (2024).

Sanyal, A. J. et al. A phase 2 randomized trial of survodutide in MASH and fibrosis. N Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2401755 (2024).

Jones, G. S., Alvarez, C. S., Graubard, B. I. & McGlynn, K. A. Agreement between the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver Disease determined by transient elastography and fatty liver indices. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20(e222), 227–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2020.11.028 (2022).

Koehler, E. M. et al. External validation of the fatty liver index for identifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 1201–1204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.031 (2013).

Funding

This work was supported by Fundings for Clinical Trials from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School (2022-LCYJ-PY-06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ and WX designed the study. YW and XZ contributed to data collection and analyses, drafted the first version of the manuscript and revised the manuscript. ZC, BW and RZ collected the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University Medical School. Each patient has signed an informed consent before enrolling into the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Chen, Z., Wei, B. et al. Metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease is associated with atrial fibrillation recurrence following cryoballoon ablation. Sci Rep 15, 6287 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90667-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90667-z