Abstract

Stirred vessels are considered as the essential equipment in chemical and process industries. This research aims to simulate the impact of 33 distinct impeller designs on the mixing quality of solid–liquid stirred vessels in terms of solid cloud volume by the CFD technique. The RNG \(k-\varepsilon\) model was employed to simulate turbulence, along with the Eulerian–Eulerian approach for multiphase flow. The impeller motion was simulated using the MRF methodology. The influence of various impeller shapes on the solid–liquid mixing was explored across three distinct parts (Part I, II, and III). In Part I, three sets of impeller shapes including pitched blade (Part I—Set I), curved blade (Part I—Set II), and other shapes of impellers (Part I—Set III) were studied. Among the impellers in Part I, the pitched blade impeller with four \(45^\circ\) blades (PB-45d-4B) in Set I, the curved blade impeller with four \(45^\circ\) blades (CB-45d-4B) in Set II, and the A320 impeller in Set III reached the maximum solid cloud volume in their set. In Part II, by changing the blades numbers of Part I impellers, the pitched blade impeller with three \(45^\circ\) blades (PB-45d-3B) increased solid cloud volume up to 72% of vessel volume. In Part III, some geometrical modifications of the PB-45d-3B impeller in terms of twelve new impeller shapes showed adding a vertical blade to the main blades and a ring around the impeller increases the solid cloud volume up to 91.16% of vessel volume.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stirred vessels serve as crucial mixing apparatus in multiphase processes and find extensive application across various industries, including chemical, mineral, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and many other industries. For this reason, studying stirred vessels and optimizing their mixing quality has received a lot of attention from researchers. Meanwhile, solid–liquid mixing systems are extensively employed in the chemical industries to augment mass transfer by homogenization of the dispersion solid phase in the liquid phase. In industrial processes, proper mixing performance is crucial and is achieved both macro and micro mixing. Micro-mixing governs chemical reactions and mass transfer, while macro-mixing occurs through mixing at the macro level. The efficiency of mixing is impacted by various elements, including the critical suspension speed, the velocity of suspension, and the distribution of solids.

In recent decades, the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) technique has been widely used to study the flow field behavior in solid–liquid stirred vessels. During the last few years, researchers have examined various approaches to find a better prediction of the flow field in the liquid–solid stirred vessels. Table 1 shows some recent studies about CFD simulation of solid–liquid stirred vessels and their achievements. According to Table 1, researchers investigated the effect of different simulation approaches such as Eulerian–Eulerian (\(E-E\)) and Eulerian–Lagrangian (\(E-L\)) multiphase models, standard \(k-\varepsilon\), RNG \(k-\varepsilon ,\) and Reynolds Stress Model (RSM) turbulent models to improve the CFD results. Their results show \(E-E\) and \(k-\varepsilon\) are the most widely used approaches for multiphase and turbulent modeling in CFD simulations of solid–liquid stirred vessels, respectively. Additionally, Table 1 shows that Schiller–Naumann and Gidaspow drag models are the most commonly used drag models to predict solid–liquid interphase momentum interaction.

While prior CFD studies on solid–liquid stirred vessel (as summarized in Table 1) have focused on refining CFD simulation methods (e.g., turbulence modeling, drag models, multiphase approaches), comparatively little attention has been paid to systematically evaluating how impeller geometry affects mixing performance. This gap is critical because impeller design directly influences solid phase suspension and performance of stirred vessel. This work provides the comprehensive CFD-based comparison of 33 distinct impeller geometries and their effects on solid cloud volume, a key indicator of mixing quality. The study aims to establish a quantitative framework for selecting optimal impeller designs to maximize solid cloud volume. This directly addresses a practical need in chemical processing, pharmaceuticals, and where impeller choice significantly impacts process efficiency.

CFD model

Governing equations

Continuity and momentum equations

In the current study the Eulerian–Eulerian multiphase model was employed to describe the continuity and momentum equations of the solid and liquid phases as follows:

where \(\alpha\), \(\rho\), \(u\), \(P\), and \(g\) represent the volume fraction, density, velocity, pressure, and gravity acceleration, respectively. The parameter \({\overline{\overline{\tau }}}_{q,eff}\) is the effective stress–strain tensor of the \({q}^{th}\) phase under turbulent conditions and it is defined by the following expression:

where \({\mu }_{lam,q}\) and \({\mu }_{t,q}\) represent the laminar and turbulent flow viscosity of the \({q}^{th}\) phase, respectively. It should be mentioned that according to Tamburini et al.3 the turbulent viscosity \({\mu }_{t}\) for the solid phase is neglected and the solid phase molecular viscosity is assumed equal to the liquid phase.

The parameter \({F}_{drag}\) in Eq. (2) is the drag force between solid and liquid phases that is calculated by the following equation:

where \({C}_{D}\) is the drag coefficient. Here, the Schiller-Naumann19 drag coefficient was used to evaluate \({C}_{D}\) as:

Turbulent flow equations

The RNG \(k-\varepsilon\) mixture turbulent model20 was used to resolve the turbulent flow field in the stirred vessel. The \(k\) and \(\varepsilon\) equations based on the mixture properties in the RNG \(k-\varepsilon\) mixture turbulent model is defined by the following equations:

where \({k}_{m}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{m}\) are the mixture turbulent kinetic energy and the mixture turbulent energy dissipation rate, respectively. Also, the parameters \({\sigma }_{k}=0.72\) and \({\sigma }_{\varepsilon }=0.72\) in Eqs. (7) and (8) are the turbulent Prandtl numbers for \(k\) and \(\varepsilon\) equations, and quantities of \({C}_{1\varepsilon }=1.42\) and \({C}_{2\varepsilon }=1.68\) in Eq. (8) are constants, respectively21,22. The parameter \({G}_{k,m}\) in Eqs. (7) and (8) is production of turbulence kinetic energy which is evaluated based on the Boussinesq model as:

where \({\mu }_{t,m}\) is the turbulent viscosity which is calculated by using the following equation:

where \({C}_{\mu }=0.09\) is constant.

Numerical method

To numerically tackle the equation set, the finite volume method was utilized. For the adjustment of the pressure–velocity flow field, the SIMPLE algorithm (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-linked Equations) was applied. The momentum and continuity equations were discretized by the QUICK (Quadratic Upwind Interpolation for Convective Kinematics) scheme. The second-order Upwind method was used to discretize the turbulent model equations. The stirred vessel impeller rotation was simulated using the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) method. The simulations were solved using a time step size of 0.0001 s under dynamic conditions, and the number of \({10}^{5}\) time steps was defined during the calculations. The numerical equations were solved by a computational server including 32 Core (Intel® Xeon 2.2 GHz CPU) and 24 GB RAM DDR3.

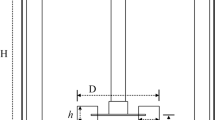

Geometrical specifications of the stirred vessel

Figure 1 illustrates the geometric specifications of the vessel utilized in the CFD simulation. The vessel body is a cylinder with a flat bottom and is equipped with four baffles and one impeller. In this study, the MRF zone dimensions were selected based on established recommendations from prior CFD studies. The vertical extension of the MRF zone was set to approximately 2.5 times the blade height, as recommended by Oshinowo et al.23 and Coroneo et al.24 to minimize artificial swirl formation at the interface. Also, the diameter of the MRF zone was positioned midway between the blade tip and the inner edge of the baffles, ensuring a balanced transition between rotating and stationary regions (Shi and Rzehak25 and Coroneo et al.24).

Geometry of impellers

This study consists of three main parts to investigate the impact of different impeller shapes on the performance of solid–liquid mixing in the stirred vessel. The first part (Part I) comprises three sets of axial flow impellers. The first set (Part I—Set I) includes Pitched Blade (PB) impellers, the second set (Part I—Set II) consists of Curved Blade (CB) axial flow impellers and the third set (Part I—Set III) includes other forms of axial flow impellers. The second part (Part II) involves the geometrical modification of the selected impellers in the first part based on the CFD simulation results and the third part (Part III) introduces new designs that are based on the CFD results from the second part with geometrical improvement in the impeller shape to enhance mixing performance.

In the impellers of Part I—Set I, four 4-bladed pitched blade (PB) impellers with blade angles of 15 (PB-15d-4B), 30 (PB-30d-4B), 45 (PB-45d-4B) and 60 (PB-60d-4B) degrees were examined. Figure 2 presents the impellers’ geometry and dimensions of Part I—Set I. The impellers of Part I—Set II consist of six 4-curved blade impellers with curvature angles of 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, and 90° and blade rotation angle of \(30^\circ\). The geometry and dimensions of Part I—Set II impellers are presented in Fig. 3. At the final set of Part I (Part I—Set III), six axial flow impellers with different structures were examined. Figure 4 shows the geometry of the impellers in Part I—Set III.

In the second part (Part II), the effect of the blades numbers for selected impellers in Part I was investigated on the quality of mixing. It should be noted that the selected impellers in Part I were investigated by CFD simulation results that will be presented in "Impellers of part II" section (The selected impellers are: PB-45d-4B and A320-30d-3B). Figure 5 presents the geometry of PB-45d and A320 impellers with two blades (PB-45d-2B and A320-45d-2B), three blades (PB-45d-3B and A320-45d-3B), and four blades (PB-45d-4B and A320-45d-4B).

In the third part (Part III), the effect of various geometrical modifications including blade angle, blade edge sharpness, blade curvature, ring around blades, and adding vertical blades to the main blade were studied on the mixing quality. These modifications were implemented on the PB-45d-3B impeller which is the best impeller of Part II ("Impellers of part III" section). In Part III, twelve new geometries were presented under the titles of Case-A to Case-L. Figure 6 shows the geometry of the studied impellers in Part III. In Case-A a 90° angled edge was added to the blade tip of the PB-45d-3B impeller. In Case-B, the PB-45d-3B impeller blades were designed with sharp tips. In Case-C, the edges of the PB-45d-3B impeller were designed as a curve shape. In Case-D, a ring was added around the PB-45d-3B impeller blades to prevent radial flow behavior. Case-E applied upward and downward flow by changing the blade angle at the end of the PB-45d-3B impeller blade. In Case-F, a vertical blade with a \(45^\circ\) angle was added to the lower surface of each PB-45d-3B impeller blade to improve the flow circulation in the lower part of the vessel. The impeller of Case-G was similar to that of Case-F, except that the additional blade does not rotate \(45^\circ\) with respect to the main blades. Cases H and I were two models of impeller with broken blades. Case-J was a combination of Cases B and D. The impeller of Case-K was a combination of Cases D and G. In Case-L, the features of cases B, G, and D were combined.

Boundary and operational conditions

The simulation employed the no-slip boundary condition for vessel walls and the standard wall function method was applied to investigate the wall effects on the flow field. The impeller rotation speed of 700 rpm was considered in all simulations. The density of liquid and solid phases was defined as \({\rho }_{L}=1000\, \text{kg}/{\text{m}}^{3}\) and \({\rho }_{S}=1300\, \text{kg}/{\text{m}}^{3}\), respectively. Also, the solid phase includes particles with the same diameter of \({d}_{p}=1\, \text{mm}\) with loading of 3% (v/v).

Mesh independency

To investigate mesh independency from the grid size, five different mesh sizes were examined through five groups sizes, Fig. 7A. The unstructured tetrahedral meshes were used in the current study Fig. 7B. The relative error was evaluated to be less than 1.3%, between the Mesh 4 and Mesh 5 for the time averaged of impeller power number and standard deviation of solid volume fraction. So, Mesh 4 was selected for CFD simulations as the appropriate mesh due to its faster solution time and accuracy.

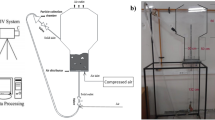

CFD model validation

To validate the CFD simulation models and numerical methods, Micheletti et al.26 experimental data was used in this work. They used a flat bottomed and cylindrical tank with internal diameter T = 290 mm and the height of H = T. Four equally spaced vertical wall baffles of width B = T/10 and thickness W = T/100 were located around the tank. The Rushton impeller with six-flat-blade impeller of diameter D = 0.098 m set at C = T/3 from bottom was used at their experimental work. Micheletti et al.26 used 600–710 \(\upmu m\) particles at 9.2% concentration in water. In the CFD validation model at this work, the average diameter of 655 \(\upmu m\) was used for the particles (solid phase). The CFD simulation results and experimental data26 are presented in Fig. 8 at three different impeller speeds. The average error between CFD results and experimental data was achieved by about 28%. Discrepancies between CFD results and experimental data may arise from neglecting lift, virtual mass, and turbulent dispersion forces. This exclusion was proposed by Ljungqvist and Rasmuson27 due to the insignificance of these forces compared to the drag force. Additionally, the use of a constant particle diameter in the CFD model may contribute to discrepancies between experimental data and numerical results.

Comparison between CFD simulation results with Micheletti et al. 26 experimental data at different impeller speed.

Results and discussion

Impellers of part I

Impellers of part I—set I

Figure 9 depicts the time averaged solid volume fraction contours and liquid velocity vector in the \(x-y\) plane for the impellers of the Part 1—Set—1 (Fig. 2). In the current study, the time averaged method was used to report all figures and data. The cloud volume was evaluated by the summation of the computational cells volume that have time averaged solid volume fraction between \({10}^{-6}\) up to 1. Also, Table 2 illustrates the percentage of the vessel volume that is occupied by the solid cloud volume. The percentage of occupied volume by the solid cloud is defined as a criterion of impeller ability for the flotation of the solid particles. As Fig. 9 and Table 2 indicate the PB-30d-4B impeller has the smallest solid cloud volume in comparison with other impellers in Part I—Set I. On the other hand, the PB-45d-4B and PB-60d-4B impellers have the highest solid cloud volume compared to the PB-15d-4B and PB-30d-4B impellers. Also, the velocity vectors in Fig. 9 indicated that the direction and dominant velocity vectors beneath the PB-45d-4B and PB-60d-4B impellers were towards the bottom of the vessel, whereas they were not for the PB-15d-4B and PB-30d-4B impellers. Therefore, the solid phase of the vessel bottom cannot float well for the PB-15d-4B and PB-30d-4B impellers. In comparing the performance of PB-45d-4B and PB-60d-4B impellers, it should be noted that PB-60d-4B impeller has greater rotation in blade angle. Consequently, the lower downward axial flow rate is achieved for the PB-60d-4B impeller and its solid cloud indicates a lower height with respect to the PB-45d-4B impeller. According to the quantitative results of Table 2 for impellers of Part I—Set I, the PB-45d-4B impeller has the highest percentage of occupied volume by the solid cloud in comparison with other impellers of Part I—Set I. So, the PB-45d-4B impeller was selected as the superior impeller among pitched blade impellers in this set.

Impellers of part I—set II

Figure 10 represents the contours of the solid cloud and fluid velocity vectors in the \(x-y\) plane for the Part I—Set II impellers (Fig. 3). The percentage of the vessel volume that is occupied by the solid cloud volume is presented in Table 3 for Part I—Set II impellers. Figure 10 shows that CB-15d-4B, CB-30d-4B, CB-75d-4B, and CB-90d-4B impellers have less solid accumulation in the vicinity of the impeller. As Fig. 10 depicts, the velocity vectors of CB-15d-4B, CB-30d-4B, CB-75d-4B, and CB-90d-4B impellers did not point towards the bottom of the vessel. As a result, the solid suspension ability decreases by these impellers. Furthermore, by comparing the solid volume fraction contours and velocity field vectors of two other impellers including CB-45d-4B and CB-60d-4B impellers, it could be observed that these two impellers created almost identical solid volume fraction patterns and velocity fields in the vessel. In addition, the CB-45d-4B and CB-60d-4B impellers are expected to improve solid phase flotation in the vessel due to their velocity vectors towards the bottom of the vessel. As Table 3 shows, the CB-45d-4B impeller has the highest percentage of occupied volume by solid cloud compared to other impellers of Part I—Set II. Consequently, the CB-45d-4B impeller was selected as the preeminent impeller between Part I—Set II impellers.

Impellers of part I—set III

Based on the findings of the two previous sections, the PB-45d-4B and CB-60d-4B impellers were selected as the top impellers in terms of occupied volume by solid cloud in the solid–liquid stirred vessel, respectively. In this sections, other shapes of axial flow impellers including three-blade A310-30d-3B, A320-30d-3B, A6000-30d-3B, SP-30d-3B, four-blade MP-30d-4B, and PB-ST-30d-4B impellers were investigated (Fig. 4). The angle of rotation of the blades in this part is 30°. The PB-ST-30d-4B impeller is a redesigned version of the PB-30d-4B impeller, featuring blades with sharp tips. The A310-30d-3B impeller is similar to PB-30d-3B impeller with a section of the blade being trimmed. The A6000-30d-3B impeller is identical to the A310-30d-3B impeller, except for the addition of a vertical edge at the tips of the blades. The A320-30d-3B impeller bears a resemblance to the PB-ST-30d-4B impeller, with its blade edge trimmed in a semicircular. The SP-30d-3B and MP-30d-4B impellers are propeller-style, comprising three and four blades, respectively. The results of the solid cloud volume and velocity vector for the impellers in Part I—Set III are shown in Fig. 11.

According to Fig. 11, it can be observed that the A310-30d-3B, A6000-30d-3B, PB-ST-30d-4B, SP-30d-3B, and MP-30d-4B impellers are less effective in keeping solids suspended. Furthermore, the flow vectors show that the flow direction under these impellers is not towards the bottom of the vessel. Among the other impellers examined in this set, the velocity vectors under the A320-30d-3B impeller are mostly directed toward the bottom of the vessel which causes better suspension of the solid phase at the vessel. Also, the solid cloud contour of the A320-30d-3B impeller shows a larger volume of the solid phase in the vessel compared to other impellers examined in this part. As a result, it is anticipated that the A320-30d-3B impeller will exhibit superior mixing capabilities compared to other impellers in Part I—Set III. Table 4 presents the quantitative values representing the percentage of occupied vessel volume by solid cloud for impellers in Part I—Set III. Based on the data presented in Table 4, the A320-30d-3B impeller has significantly greater capacity in suspending the solid phase in the vessel compared to other impellers in Part I—Set III.

Impellers of part II

An examination of the axial flow impellers of the first part impellers (Part I—Set I, Set II, and Set III) showed that the PB-45d-4B and A320-30d-3B impellers have a better ability in the suspension of the solid phase compared to other impellers. Considering that the PB-45d-4B impeller is composed of 4 blades arranged at a 45 angle, while the A320-30d-3B impeller encompasses 3 blades positioned at a 30 angle, this section incorporates an assessment and comparison of the influence of blade numbers mixing quality. To this aim, the geometries of these two impellers (PB-45d-4B and A320-30d-3B) have been studied with two, three, and four blades. Also, according to reported results in Part I- Set I (Pitched blade impellers) and Part I—Set II (Curved blade impellers), the best blade angle for solid–liquid mixing was achieved at 45°. So, in Part II impeller’s blade angle was fixed at 45°. Therefore, the A320-30d-3B impeller blade angle has been modified from 30 to 45 (A320-45d-3B). The geometry of the impellers in Part II was presented in Fig. 5. Figure 12 shows the contours of solid cloud volume and velocity vector for the pitched blade impellers, including the PB-45d-2B, PB-45d-3B, and PB-45d-4B impellers. According to the appropriate pattern of flow velocity vectors under pitched blade impellers of Part II (Fig. 12), the performance of pitched blade impellers was assessed using the data from Table 5. The results of Table 5 showed that the PB-45d-3B impeller has the highest percentage of the occupied volume by solid cloud in the vessel. So, the PB-45d-3B impeller has been selected as the best impeller in comparison to the pitched blade impellers of Part II.

Figure 13 illustrates the contour of the solid cloud and the velocity vector for A320-45d-2B, A320-45d-3B, and A320-45d-4B impellers. Like the assessment of pitched blade impellers, the performance of A320 impellers in Part II is evaluated by the percentage of the occupied volume by the solid cloud which is presented in Table 6. The data in Table 6 indicates that the A320-45d-3B impeller has the largest solid cloud volume within the vessel. As a result, the A320-45d-3B impeller is the most efficient impeller to fluidize solid phase in compared to the A320-45d-2B and A320-45d-4B impellers.

According to the results of Part II impellers, the PB-45d-3B and A320-45d-3B impellers were selected as the efficient impellers in this part. However, due to the similarity in their ability to fluidize the solid phase, as indicated by the occupied volume by solid cloud (Tables 5 and 6), further analysis of their power (\({N}_{P}\)) and pumping (\({N}_{Q}\)) numbers was conducted. The power and pumping numbers were evaluated by the following equations:

where \(T\), \(D\), \(N\), \(\rho ,\) and \(Q\) are torque, impeller diameter, rotational speed, liquid density, and volumetric flow rate, respectively. Figure 14 shows the power and pumping numbers of the PB-45d-3B and A320-45d-3B impellers. As shown in Fig. 14A, the PB-45d-3B impeller’s power number is approximately 1.2% greater than that of the A-320-3B impeller. A higher power number may suggest a greater pumping capacity for the impeller. When comparing the pumping numbers of the PB-45d-3B and A320-45d-3B impellers, it is evident that the PB-45d-3B impeller’s pumping capacity exceeds that of the A320-45d-3B impeller by about 3%. According to the results, although there is not much difference between the power and pumping numbers between PB-45d-3B and A320-45d-3B impellers, considering the importance of pumping ability and solid cloud volume, the PB-45d-3B impeller has been selected as the best impeller in Part II.

Impellers of part III

In the previous section (Part II impellers), the PB-45d-3B impeller was determined as the most effective axial flow impeller to fluidize solid particles. This part examines the performance of modified impellers for improvement of solid–liquid mixing by adding features such as a curved edge, vertical edge, sharp tip blade, ring around the impeller, and a break in the impeller blades to the PB-45d-3B impeller geometry. Finally, by comparing the results of CFD simulations, the best impeller in terms of occupied volume by solid cloud is introduced. The geometry of the impellers examined in Part III (Case-A to Case-L) was shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 15 shows the solid cloud contour and velocity vectors for Cases A to L. By comparing the solid cloud contour results, it can be seen that Cases A, B, C, K, and L can suspend more solid phases and form the larger solid clouds. To quantify the results, Table 7 presents the percentage of the occupied volume by the solid cloud in the vessel for impellers of Part III. The results show that Case-K possesses the highest capacity for suspending solid phase. Nonetheless, the difference between Case-K and Cases A, B, C, and L is less than 4%. As a result, to identify the optimal impeller among those mentioned, their power and pumping numbers have been examined. Figure 16 presents the power and pumping numbers of Part III impellers. As depicted in Fig. 16, the Case-K impeller registers the maximum power usage in comparison to the other impellers in Part III. The power consumption of Case-K impeller is approximately 5.2% greater than the average power consumption of Cases A, B, C, and L impellers. Also, it should be noted that the pumping number of Case-K is about 0.5% higher than the average pumping number of Cases A, B, C, and L impellers. As a result, the impeller of Case-K can be considered the most efficient impeller of Part III based on the studied hydrodynamic parameters and suspension of the solid phase.

Conclusion

This article investigated the effects of various impeller shapes on the mixing quality of a two-phase solid–liquid stirred vessel by the CFD technique. The impact of impeller designs on the quality of mixing was investigated for 33 different shapes of impellers in three main parts (Part I (including three sets), Part II, and Part III). The most important findings by CFD simulation are as follows:

-

In Part I—Set I (pitched blade impellers), the best angle of blade rotation for attaining the highest solid cloud volume was achieved at 45° (PB-45d-4B impeller).

-

In Part I—Set II (curved blade impellers), the best curvature angle for achieving the highest solid cloud volume was found to be 45° (CB-45d-4B).

-

In Part I—Set III (other shapes of axial flow impellers), the highest solid cloud volume was achieved by the A320-30d-3B impeller.

-

In Part II, according to CFD simulation results of Part I, with selection of angle blade of \(45^\circ\) as the best angle to reach the highest solid cloud volume, the effect of numbers of impeller blades on the performance of the pitched blade and A320 impellers was studied. Results showed the PB-45d-3B impeller (three blades with \(45^\circ\) angle) have the highest solid cloud volume between impellers of Part I and Part II impellers.

-

In Part III, twelve new shapes of impellers (Cases A to L) based on PB-45d-3B impeller were designed. The CFD simulation results demonstrated that the addition of a blade oriented perpendicularly to the primary blades of the impeller, along with the inclusion of a ring encircling the blade (Case-K) enhances the solid cloud volume to 91.16% of the vessel volume. So, the Case-K impeller was selected as the best impeller between Parts I, II, and III impellers to maximize solid suspension in the solid–liquid stirred vessel.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \({C}_{D}\) :

-

Drag coefficient (Dimensionless)

- \({C}_{1\varepsilon }, {C}_{2\varepsilon }\) and \({C}_{\mu }\) :

-

Constants (Dimensionless)

- \(D\) :

-

Impeller diameter (m)

- \({d}_{p}\) :

-

Particle diameter (m)

- \({F}_{drag}\) :

-

Solid–liquid interphase drag force (kg/m2 s2)

- \({G}_{k,m}\) :

-

Turbulent kinematic energy production (kg/m s3)

- \(g\) :

-

Gravity \((\text{m}/{\text{s}}^{2})\)

- \(k\) :

-

Turbulent kinetic energy \(({\text{m}}^{2}/{\text{s}}^{2})\)

- \(N\) :

-

Impeller rotation velocity \((\text{rpm})\)

- \({N}_{p}\) :

-

Power number (Dimensionless)

- \({N}_{Q}\) :

-

Pumping number (Dimensionless)

- \(P\) :

-

Pressure (kg/m s2)

- \(Q\) :

-

Volumetric flow rate \(({\text{m}}^{3}/\text{s})\)

- \(R{e}_{p}\) :

-

Particle Reynolds number (Dimensionless)

- \(T\) :

-

Torque (kg m2/s2)

- \({\alpha }_{q}, {\overline{\alpha }}_{q}\) :

-

Volume fraction and time averaged volume fraction for \({q}{th}\) phase

- \({\alpha }_{k} \,and\, {\alpha }_{\varepsilon }\) :

-

Inverse of turbulent Prandtl numbers for \(k\) and \(\varepsilon\)

- \(\beta\) :

-

Constant \((\beta =0.012)\)

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Turbulent dissipation rate \(({\text{m}}^{2}/{\text{s}}^{3})\)

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density (kg/m3)

- \({\eta }_{0}\) :

-

Constant \(({\eta }_{0}=4.377)\)

- \(\mu\), \({\mu }_{t}\) and \({\mu }_{eff}\) :

-

Laminar, turbulent, and effective viscosity (kg/m2 s)

- \(\overline{\overline{\tau }}\) :

-

Effective stress–strain tensor (kg/m s2)

References

Hosseini, S., Patel, D., Ein-Mozaffari, F. & Mehrvar, M. Study of solid−liquid mixing in agitated tanks through computational fluid dynamics modeling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 49, 4426–4435 (2010).

Sardeshpande, M. V., Juvekar, V. & Ranade, V. V. Solid suspension in stirred tanks: UVP measurements and CFD simulations. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 89, 1112–1121 (2011).

Tamburini, A., Cipollina, A., Micale, G., Brucato, A. & Ciofalo, M. CFD simulations of dense solid–liquid suspensions in baffled stirred tanks: Prediction of suspension curves. Chem. Eng. J. 178, 324–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.10.016 (2011).

Feng, X., Li, X., Cheng, J., Yang, C. & Mao, Z.-S. Numerical simulation of solid–liquid turbulent flow in a stirred tank with a two-phase explicit algebraic stress model. Chem. Eng. Sci. 82, 272–284 (2012).

Tamburini, A., Cipollina, A., Micale, G., Brucato, A. & Ciofalo, M. Influence of drag and turbulence modelling on CFD predictions of solid liquid suspensions in stirred vessels. Chem. Eng. Res. Design 92, 1045–1063 (2014).

Wadnerkar, D., Pareek, V. K. & Utikar, R. P. CFD modelling of flow and solids distribution in carbon-in-leach tanks. Metals 5, 1997–2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/met5041997 (2015).

Wadnerkar, D., Tade, M. O., Pareek, V. K. & Utikar, R. P. CFD simulation of solid–liquid stirred tanks for low to dense solid loading systems. Particuology 29, 16–33 (2016).

Mishra, P. & Ein-Mozaffari, F. Using computational fluid dynamics to analyze the performance of the Maxblend impeller in solid-liquid mixing operations. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 91, 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2017.01.009 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Numerical simulation of flow behavior of particles in a liquid–solid stirred vessel with baffles. Adv. Powder Technol. 28, 1611–1624 (2017).

Li, G. et al. Particle image velocimetry experiments and direct numerical simulations of solids suspension in transitional stirred tank flow. Chem. Eng. Sci. 191, 288–299 (2018).

Maluta, F., Paglianti, A. & Montante, G. RANS-based predictions of dense solid–liquid suspensions in turbulent stirred tanks. Chem. Eng. Res. Design 147, 470–482 (2019).

Kazemzadeh, A., Ein-Mozaffari, F. & Lohi, A. Effect of impeller type on mixing of highly concentrated slurries of large particles. Particuology 50, 88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.partic.2019.07.004 (2020).

Gu, D., Ye, M. & Liu, Z. Computational fluid dynamics simulation of solid-liquid suspension characteristics in a stirred tank with punched circle package impellers. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 18, 20200026 (2020).

Stuparu, A., Susan-Resiga, R. & Bosioc, A. CFD simulation of solid suspension for a liquid-solid industrial stirred reactor. Appl. Sci. 11, 5705 (2021).

Mishra, P. & Ein-Mozaffari, F. Using flow visualization and numerical methods to investigate the suspension of highly concentrated slurries with the coaxial mixers. Powder Technol. 390, 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2021.05.078 (2021).

Jadhav, A. J. & Barigou, M. Eulerian–Lagrangian modelling of turbulent two-phase particle-liquid flow in a stirred vessel: CFD and experiments compared. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 155, 104191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2022.104191 (2022).

Gu, D., Song, Y., Xu, H., Wen, L. & Ye, M. CFD simulation and experimental analysis of solid-liquid mixing characteristics in a stirred tank with a self-similarity impeller. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 146, 104878 (2023).

Yin, C. et al. Improved suspension quality and liquid level stability in stirred tanks with Rotor-Stator agitator based on CFD simulation. Particuology 82, 64–75 (2023).

Schiller, L. & Naumann, Z. A drag coefficient correlation. Z. Ver. Deutsch. Ing, 77–318 (1935).

Yakhot, V. & Orszag, S. A. Renormalization group analysis of turbulence. I. Basic theory. J Sci. Comput. 1, 3–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01061452 (1986).

Yakhot, V. & Smith, L. M. The renormalization group, the ɛ-expansion and derivation of turbulence models. J. Sci. Comput. 7, 35–61 (1992).

Yakhot, V., Orszag, S., Thangam, S., Gatski, T. & Speziale, C. Development of turbulence models for shear flows by a double expansion technique. Phys. Fluids A Fluid Dyn. 4, 1510–1520 (1992).

Oshinowo, L., Jaworski, Z., Dyster, K. N., Marshall, E. & Nienow, A. W. In 10th European Conference on Mixing (eds H. E. A. van den Akker & J. J. Derksen) 281–288 (Elsevier Science, 2000).

Coroneo, M., Montante, G., Paglianti, A. & Magelli, F. CFD prediction of fluid flow and mixing in stirred tanks: Numerical issues about the RANS simulations. Comput. Chem. Eng. 35, 1959–1968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2010.12.007 (2011).

Shi, P. & Rzehak, R. Bubbly flow in stirred tanks: Euler-Euler/RANS modeling. Chem. Eng. Sci. 190, 419–435 (2018).

Micheletti, M., Nikiforaki, L., Lee, K. C. & Yianneskis, M. Particle concentration and mixing characteristics of moderate-to-dense solid–liquid suspensions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 42, 6236–6249 (2003).

Ljungqvist, M. & Rasmuson, A. Numerical simulation of the two-phase flow in an axially stirred vessel. Chem. Eng. Res. Design 79, 533–546 (2001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Heidari conceptualized the research framework, designed, conducted the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), and provided overall supervision for the project. He also critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. A. Risheh conducted the Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations and performed data analysis. He contributed significantly to the writing of the methodology and results sections of the manuscript. Z. Mehdiabadi contributed significantly to the writing of the paper and some general analysis in the simulation results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heidari, A., Risheh, A. & Mehdiabadi, Z. CFD simulation of impeller shape effect on the solid cloud volume in the solid and liquid stirred vessel. Sci Rep 15, 6674 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90700-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90700-1