Abstract

During the tunneling process in high-temperature environments, the surrounding rock mass is subjected to periodic pressurization and depressurization, making it prone to instability and failure. To investigate the damage and failure of high-temperature rock under cyclic loading-unloading, uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading tests and ABAQUS numerical simulations were conducted on granite samples at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, 75 ℃, and 100 ℃. The acoustic emission characteristics and Kaiser effect of the granite were studied, along with the changes in mechanical properties and damage failure characteristics under cyclic loading-unloading. The results indicate that: (1) Under cyclic loading-unloading, the peak strength of granite initially decreases and then increases as temperature rises, Notably the minimum peak strength and maximum area of the hysteresis loop are observed at 75 ℃. (2) Under different temperature conditions, the Felicity ratio of granite increases with the number of loading cycles and eventually converging towards a value of 1. However, the rate of increase gradually diminishes progressively, and the Kaiser effect becomes increasingly pronounced. (3) Further numerical simulation studies were conducted on granite at 50 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 80 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃. The identification of Kaiser points through the analysis of fractured unit volume is consistent with the cumulative acoustic emission ringing count methodology, Furthermore, the Felicity ratio of granite exhibits a negative correlation with the extent of damage. (4) As the temperature and the number of cycles increase, the damage variable of granite initially increases before subsequently declining, with its maximum observed at 80 ℃. The results indicate potential risks of structural failure in high-temperature granite subjected to cyclic loading-unloading, thereby offering valuable insights for engineering construction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During tunnel or roadway excavation, rock masses are often subjected to cyclic loading-unloading effects caused by blasting vibrations and mechanical disturbances. This cyclic loading-unloading can induce the initiation, development, and coalescence of microcracks in surrounding rock, eventually leading to instability or rockburst1. Intense acoustic emission activity often accompanies the instability or rockburst of surrounding rock. In recent years, As the number of high-temperature rock engineering projects increases, accompanied by a corresponding rise in construction challenges, which has garnered widespread attention from scholars both domestically and internationally2. The characteristics of real-time damage in high-temperature rock subjected to cyclic stress, as well as the changes in physical and mechanical properties of the rock, remain to be explored. The investigation of the Kaiser effect in rocks subjected to different temperatures under cyclic loading-unloading is essential for predicting instability and provides early warnings for potential disasters. This is of great engineering significance for stability analysis and construction of underground projects3.

The Kaiser effect refers to the phenomenon observed in materials where, during loading and unloading, the material does not show any new stress response or acoustic emission when reloaded below the stress level previously experienced. By studying the Kaiser effect, we can better understand the macroscopic and microscopic damage processes in materials. Numerous researchers have delved into the Kaiser effect in rocks. Tang4 examined the influence of stress level and holding time on the Kaiser effect of granite, discovering that acoustic emission signals for identifying the Kaiser effect originate from crack closure under low stress levels and from crack generation and propagation under high stress conditions. Zhang et al.5 used acoustic emission technology to monitor granite’s uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading tests in real time, demonstrating the reliability of using the Felicity ratio to quantify the Kaiser effect. Miao et al.6 conducted stepwise cyclic loading tests on sandstone under different stress levels, confirming that the compression-rebound effect of pores leads to the failure of the Kaiser effect in sandstone. Zhang et al.7investigated the influence of loading rate on the Kaiser effect through uniaxial compression tests on different rock types under varying confining pressures, revealing that stress corresponding to the Kaiser effect point changes with loading rates for different rock types. However, these studies did not consider the influence of temperature on the Kaiser effect in rocks. Tan8explored the thermal Kaiser effect in different rock materials under various thermal treatment cycles, concluding that granite and marble exhibit significant thermal Kaiser effects after undergoing multiple temperature treatments, whereas red sandstone shows negligible thermal Kaiser effects. Ge9 analyzed the acoustic emission characteristics of Niutitang shale under real-time high-temperature conditions, noting a thermal Kaiser effect threshold temperature of approximately 180℃. Yang et al.10 investigated the effects of temperature on stress-induced damage in granite, demonstrating that the Kaiser effect becomes more pronounced at high stress levels after 120℃ and 250℃ treatments. Wu et al.11 found that the Kaiser effect in granite weakens with increasing temperature after high-temperature treatments, causing the deformation memory of previous stress loads to diminish.

While these studies offer valuable insights into how loading stress, loading rate, rock type, and temperature influence acoustic emission characteristics and the Kaiser effect, most research has focused on ultra-high temperatures above 100 ℃. However, in China’s tunnel construction projects, rock temperatures are generally below 100 ℃12. Consequently, there is a notable deficiency in studies on the acoustic emission characteristics and the Kaiser effect of rocks under cyclic loading-unloading below 100 ℃. Therefore, in this study, granite samples were initially subjected to heating at various temperatures (30 ℃–100 ℃). Uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading tests with varying upper limits were then conducted to analyze the stress-strain curves and acoustic emission characteristics of granite samples under different temperature conditions. Subsequently, numerical simulations of the Kaiser effect were performed to further analyze the influence of temperature. Finally, the relationship between damage failure and the Kaiser effect was discussed. The findings provide theoretical guidance for controlling the stability of high-temperature rocks under cyclic loading-unloading.

Uniaxial compression test of granite under cyclic loading-unloading at different temperatures

Specimen preparation and testing scheme

Granite samples were collected from the Sangzhuling Tunnel in Tibet. In accordance with the Standard for Test Methods of Engineering Rock Mass (GBT50266-2013)13, the granite was cored, cut, and polished into standard cylindrical specimens in the laboratory. Each specimen had a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm, with end surfaces perpendicular to the central axis and uniformly flat. The specimens exhibited no significant joint abnormalities. To monitor the mechanical behavior and damage characteristics, two strain gauges were attached horizontally and vertically at the side of each specimen, 50 mm from the top and bottom ends. Additionally, six acoustic emission (AE) sensors were adhered at 20 mm from the top and bottom surfaces during uniaxial compression. The arrangement of strain gauges and AE sensors is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the prepared granite specimens are shown in Fig. 2.

The experimental temperatures selected in this study are 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, 75 ℃, and 100 ℃. The current research primarily focuses on rocks subjected to ultra-high temperatures (≥ 150 ℃). However, in the context of tunnel excavation in China, the engineering environment typically involves temperatures below 100 ℃14. There is a lack of studies on the mechanical damage characteristics and constitutive relationships of rocks under cyclic loading and unloading within the temperature range of 28 ℃ to 100 ℃. Considering the impact of cyclic loading on rock masses during tunnel excavation construction, the loading path for the experiments was chosen as a variable upper-limit cyclic loading-unloading. The loading intensity was increased by 10 MPa with each cycle compared to the previous load, until specimen failure occurred.

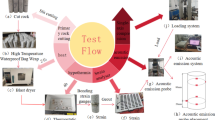

Experimental equipment and procedure

The experimental system comprises three components: a heating and insulation system, a loading system, and a data acquisition system. (1) The heating and insulation system consists of an electric blast drying oven and spring heating coils controlled by a thermal flow path temperature control box. (2) The loading system employs a WAW-1000B microcomputer-controlled servo hydraulic universal testing machine. (3) The data acquisition system includes strain gauges, an acoustic emission transducer, a spoke-type pressure sensor, a Stress-Strain Data Acquisition Instrument, a DATALOGGER TDS-530 high-speed static data acquisition instrument, and an Express8 acoustic emission host.

Standard granite specimens were dried in an electric blast drying oven for 24 h to minimize the impact of internal pore water. Subsequently, the specimens were heated in the oven to the desinated target temperature for an additional 24 h prior to moval15. To avoid temperature drops when exposed to room conditions, which could introduce testing errors, the specimens were insulated using spring heating coils controlled by the thermal flow path temperature control box after removal from the oven. Specimens subjected to the insulation system were placed in the hydraulic testing machine to conduct cyclic loading and unloading tests. During these tests, the stress-strain data and acoustic emission data of the granite specimens were collected using the data acquisition system. The experimental system and process are shown in Fig. 3.

Uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading tests were performed on the rock specimens, with both loading and unloading rates set at 1.0 MPa/s. The schematic representation of the loading and unloading path is shown in Fig. 4.

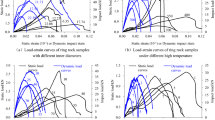

Stress-strain curves of granite after cyclic loading and unloading

Temperature and cyclic loading and unloading affect the generation and development of weak points, such as pores and microcracks, within the rock. Stress-strain curves reflect the mechanical properties and deformation characteristics of rock and can indicate the Kaiser effect observed in granite16. By fitting the peak strength and vertical strain recorded during each loading-unloading cycle of granite, it is possible to derive the complete stress-strain fitting curve for uniaxial compression, as illustrated in Fig. 5(a). The curve can be approximately categorized into five distinct stages: Crack compaction stage (OA); Linear elastic stage (AB); table crack propagation stage (BC); Rapid crack propagation stage (CD); Post-peak failure stage. Stress-strain curves and their corresponding fitted curves for granite samples under different temperatures and cyclic loading-unloading conditions are shown in Fig. 5(b)–(f).

Analyzing Fig. 5(b)–(f), the stress-strain curves of granite after cyclic loading and unloading under various temperature conditions exhibit concave upward shapes. Pre-peak curves exhibit a smooth profile, while some post-peak curves at specific temperatures appear linear, indicating brittle failure as a result of through-going fractures within the specimens. Compared to 30 ℃, stress-strain curves of granite specimens under other temperature conditions exhibit more pronounced initial concavity and prolonged compaction phases, This phenomenon can be attributed to the rise in temperature, which induces thermal damage and results in an increase in internal defects such as pores and cracks within the samples. Under external loading, these internal defects gradually close. As the number of cycles increases, the internal structure of the rock becomes denser, resulting in a gradual increase in the peak strength of granite specimens, steeper curve slopes, and the formation of plastic hysteresis loops in each loading and unloading cycle. The area of these loops initially increases and subsequently decreases with continued cycling, while the slope of the unloading curve (representing the elastic modulus of the rock) gradually increases, indicating enhanced elasticity of the rock material under unloading stress. During reloading after each unloading cycle, the deformation curve continues to rise along the original monotonic loading curve once the load exceeds the maximum load of the previous cycle, demonstrating the deformation memory of granite. The hysteresis loop at 75 ℃ is sparsest and has the largest area. By taking the highest points of stress-strain curves from each cyclic loading and unloading as fitting points, the full stress-strain fitting curves of granite at various temperatures can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 5(b)–(f). Analyzing Fig. 5(b)–(f): The peak strengths of granite at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, 75 ℃, and 100 ℃ are 145.37 MPa, 136.38 MPa, 108.93 MPa, 102.83 MPa, and 158.61 MPa, respectively. The peak strength of granite exhibits an initial decreases followed by an increases as the temperatur rises, reaching a minimum at 75 ℃. In comparison to granite at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, and 100 ℃, the peak strength of 75 ℃ granite exhibits reductions of 30.1%, 25.8%, 5.4%, and 55%, respectively. This is attributed to the sparsest cyclic loading and unloading curves of 75 ℃ granite and the most pronounced hysteresis phenomenon, indicating that specimens at this temperature consume the most energy and enter the crack propagation stage more rapidly, resulting in the lowest peak strength. The cyclic loading and unloading curve of granite at 100 °C becomes denser, with no significant hysteresis loop, indicating that at this temperature, the granite consumes less energy and the crack propagation phase slows down, leading to a rebound in peak strength.

Analysis of acoustic emission characteristics of granite under cyclic loading and unloading

The cyclic stress-strain curve reflects the mechanical properties and deformation characteristics of granite under cyclic loading-unloading at different temperatures. However, the Kaiser effect of rock not only indicates its “memory ability” of past deformation but also emphasizes stress history through rock damage representation17. Using the stress-time-acoustic emission characteristic curves obtained from the experiments during the failure process of granite samples at various temperatures, the damage characteristics of granite at different temperatures can be analyzed, as shown in Fig. 6(b)–(f). The Kaiser points under various temperature conditions were identified using the tangent intersection method. This involves drawing tangents to the horizontal section and the linear sudden increase section of the cumulative ringing count curve of acoustic emission18. The intersection of these two tangents represents the Kaiser point19, which is marked by a green dot in the Figs. The stress corresponding to the Kaiser point is the maximum prior stress experienced by the granite. The method for identifying the Kaiser point is shown in Fig. 6(a).

From Fig. 6(b)–(f), it can be observed that under various temperature conditions, the cumulative ringing count curve of acoustic emission exhibits a consistent trend during the processes of cyclic loading and unloading. In the initial loading stage, only a few acoustic emission events occur. As the load gradually increases, the curve experiences two stages: stable growth and rapid growth. The phenomenon can be attributed to the compaction stage of granite samples, during which the closure of pores and cracks occurs, resulting in a limited number of acoustic emission events. In the elastic-plastic deformation stage, the granite samples experiences deformation and recovery repeatedly during loading-unloading, with stable crack propagation, which results in a gradual increase in acoustic emission events. In the post-peak failure stage, the granite becomes unstable and fails, resulting in an “explosive” increase in the acoustic emission ringing count. The cumulative acoustic emission ringing count exhibits a sudden increase, characterized by a distinct inflection point, indicating a significant Kaiser effect. Among them, the final cumulative ringing count of granite at 75 ℃ is 92 × 10⁵, which is 70.4%, 56%, 46%, and 50% higher than that of granite samples at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, and 100 ℃, respectively. This indicates that as the temperature rises, the degree of damage to granite intensifies, reaching its maximum at 75 ℃.

By calculating the number of Kaiser points in Fig. 6(b)–(f) for granite at various temperatures, the values are 11, 11, 7, 6, and 13 for 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, 75 ℃, and 100 ℃, respectively, as shown in Fig. 7. From Fig. 7 indicate that, under cyclic loading and unloading, the number of Kaiser points initially decreases and subsequently increases with rising temperature. Granite at 100 ℃ has the most Kaiser points and the most pronounced Kaiser effect, while granite at 75 ℃ has the fewest Kaiser points and the least pronounced Kaiser effect. This observation indicates that after thermal damage, granite at 75 ℃ develops more pores and cracks. In comparison to alternative temperature conditions, the ratio of the compaction and elastic stages is greater. During its failure process, the first five cycles of loading and unloading belong to the compaction and elastic stages, with almost no acoustic emission events occurring. Hence, there are fewer Kaiser points. In contrast, during the crack initiation and propagation stages as well as the post-peak failure stage, acoustic emission events increase “explosively.” This observation indicates that for granite at 75℃, only the last two cycles of loading and unloading can effectively identify Kaiser points. Consequently, the Kaiser effect is least pronounced under this temperature condition. The mechanical properties of granite at 100 °C show a significant rebound, leading to a noticeable increase in the number of cyclic loading and unloading cycles. As the granite progresses into the crack propagation and post-failure stage, the cumulative ring count curve of the granite gradually adopts a “staircase” shape. Consequently, the number of Kaiser effect points in the 100 °C granite increases.

Felicity ratio during cyclic loading and unloading

The Felicity ratio is a direct expression of the memory degree of materials and is often used to measure the effectiveness of the Kaiser effect20. A Felicity ratio in the range of 0.9–1.10 indicates a significant Kaiser effect, while values in the range of 0.85–0.9 and 1.10–1.15 suggest the Kaiser effect is present but not significant. Values outside these ranges indicate the absence of the Kaiser effect21. The Felicity ratio is defined as22:

In the equation: \({F_{\text{i}}}\) represents the Felicity ratio in the i-th cycle; \(\sigma _{i}^{{AE}}\) denotes the stress value, in MPa, corresponding to the acoustic emission burst during the i-th loading process; \(\sigma _{{i - 1}}^{m}\) indicates the maximum stress, in MPa, experienced during the (i-1)-th loading process. Based on the stress-time-acoustic emission characteristic curve, the \(\sigma _{i}^{{AE}}\)values under different temperatures and cyclic stresses are identified, allowing for the construction of the Felicity ratio versus cycle number curve23, as shown in Fig. 8.

Analysis of Fig. 8 reveals the following: Under 30 ℃, most Kaiser points of granite have a Felicity ratio in the range of 0.9–1.10, indicating a significant Kaiser effect. Under 40 ℃, the Felicity ratio of Kaiser points in the first five cycles is below 0.85, but it increases with the number of cycles in the subsequent five cycles. Under 55 ℃ and 75 ℃, the Felicity ratio of Kaiser points also increases with cycle number. However, the overall Kaiser effect under these temperatures is not significant, with the least significant Kaiser effect observed at 75 ℃. Under 100 ℃, the Felicity ratio sharply increases with cycles, and the Kaiser effect becomes significant after the seventh cycle.

Overall, in the temperature range of 30 ℃ to 100 ℃, the Felicity ratio of granite increases with the number of cyclic loading and unloading steps, eventually approaching 1. This phenomenon can be attributed to in the early stage of cyclic loading and unloading, during which internal particle sliding in granite produces friction, resulting in a series of ongoing, minor acoustic emission occurrences. This “friction-type” acoustic emission signal makes it difficult to accurately identify Kaiser points, resulting in low Felicity ratios. In the later stages, each cycle induces the generation and development of microcracks, leading to numerous acoustic emission events. The cumulative ring count in the acoustic emission characteristic curve exhibits a distinct “stepped” pattern, which signifies a pronounced Kaiser effect.

Numerical simulation of granite at different temperatures under cyclic loading and unloading

The preceding analysis indicates that temperature has a substantial impact on the Kaiser effect by granite when subjected to cyclic loading and unloading. To further analyze the influence of temperature, uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading tests of granite at different temperatures were simulated using ABAQUS.

Numerical model and validation

The dimensions of the numerical model match those of the granite samples used in the experiments. Compression plates with a diameter of 80 mm are established at the upper and lower ends of the model, and a hexahedral element neutral axis algorithm is used for mesh generation, as shown in Fig. 9. The material properties of the model are consistent with the experimentally measured values, and the failure criterion follows the Griffith fracture criterion. The temperatures and material properties of the model are shown in Table 1. In the load setting module, a load-time relationship is established in Table 2. The load varies with time during loading, achieving a cyclic loading and unloading compression mode.

The ultimate failure modes of granite under uniaxial cyclic loading and unloading conditions at various temperatures, as obtained through experimental and simulated results, are compared in Fig. 10.

Analysis of Fig. 10, Both physical experiments and numerical simulations indicate that tensile failure is the predominant mode of failure in granite across all temperatures. At the same temperature, the distribution and quantity of cracks are similar, demonstrating that the numerical simulation effectively reproduces the failure characteristics of granite observed in laboratory tests. In the numerical simulation results, the through-cracks observed in the physical experiments on granite did not appear. This discrepancy is attributed to the fact that actual rocks contain fractures and microstructures, whereas the numerical model assumes a homogeneous medium. As a result, the simulation outcomes cannot fully capture the fracture processes of real rocks. Stress-strain curves during the uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading failure process of granite were extracted from numerical simulations and compared with the stress-strain curves obtained from physical experiments. The results are illustrated in Fig. 11(a)~(e), and the fitted stress-strain curve is depicted in Fig. 11(f), with the correlation coefficients listed in Table 3.

Analysis of Fig. 11(a)–(e) reveals that the peak strengths of granite at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 55 ℃, 75 ℃, and 100 ℃ from numerical simulations are 152.89 MPa, 136.52 MPa, 115.02 MPa, 110.35 MPa, and 165.68 MPa, respectively, with differences from the experimental results within 3.2%. Moreover, as the temperature rises, the density of the cyclic stress-strain curves exhibits an initial decrease (reaching a minimum at 75 ℃), following by an increase. Therefore, the trends observed in the numerical simulation are consistent with those of the physical experiments. From Fig. 11(f) and Table 3, the comparison of the fitted stress-strain curves derived from simulations and experimental data demonstrates a strong correlation, as evidenced by correlation coefficients approximating 95%. Consequently, the comparison of the failure modes and stress-strain curves of granite specimens between laboratory tests and numerical simulations, substantiates the validity of the numerical model, This validation facilitates subsequent research into the Kaiser effect in granite.

Mechanical properties and Kaiser effect of granite at different temperatures

To accurately study the influence of temperature on the Kaiser effect, further numerical simulations were conducted for uniaxial cyclic loading-unloading tests of granite under temperatures of 50℃, 60℃, 70℃, 80℃, 90℃, and 100℃. The cumulative fractured volume and acoustic emission cumulative ringing count were used as effective indicators of granite damage and failure24. The tangent intersection method was employed to identify the Kaiser point by locating the intersection of the horizontal section and the linear sudden increase section of the cumulative fractured volume curve. The stress-cumulative fractured volume characteristic curves of the specimen during the failure process are shown in Fig. 12 where green dots indicate the Kaiser points.

Analysis of Fig. 12, At different temperatures, as the cyclic loading-unloading stress of granite increases, the cumulative fractured volume curve rises slowly. Under conditions of low stress, granite exhibits behavior characteristic of crack compaction and linear elastic stages, resulting in a minimal volume of fractures. As the stress increases to 120 MPa, 110 MPa, 103 MPa, 90 MPa, 100 MPa, and 114 MPa, the volume of the fractured granite unit experiences a sudden expansion, marking the transition to the crack propagation and instability failure stages. As temperature rises, the cumulative fractured volume curve slope begins to increase significantly at stresses of 120 MPa, 110 MPa, 103 MPa, 90 MPa, 100 MPa, and 114 MPa under 50 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 80 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃, respectively. The fractured volume reaches its maximum value of 3.26 × 10⁵ mm³ at 80℃ during granite instability failure, representing 163%, 143%, 122%, 117%, and 134% of the fractured volumes at 50 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃, respectively. This indicates that the failure intensity of granite is greatest at 80 ℃. Concurrently, the number of Kaiser points for granite decreases initially and then increases with temperature. At 80 ℃, granite specimens fail after five cycles of loading-unloading, having only four Kaiser points. This is six, four, two, two, and three fewer than the Kaiser points observed at 50 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃, respectively. The Kaiser points are concentrated within the section of the fractured volume curve where the slope increases sharply. This phenomenon occurs because the peak stress is the lowest at 80 ℃, resulting in the fewest loading cycles.

Analysis of Figs. 13 and 14, To investigate the relationship between granite temperature and Kaiser effect under numerical simulations, the relationships between the number of cycles and Felicity ratio (Fig. 13) and between temperature and the number of Kaiser points (Fig. 14) were plotted.

From Fig. 13, the trend of Felicity ratio changes under various temperature conditions in numerical simulations aligns with that observed in physical experiments. For granite at 50 ℃, the Felicity ratio increases from 0.43 to 0.89 as the number of cycles increases. At 60 ℃ and 70 ℃, the number of cycles decreases by one and five cycles compared to 50 ℃, respectively, with the number of Kaiser points decreasing to three and one, respectively. Granite at 80 ℃ exhibits the lowest number of cyclic loadings, while at 90 ℃ and 100 ℃, the number of cycles increases again to seven and eight, respectively. Concurrently, the Felicity ratio at these temperatures exhibits a progressive increase in relation to the number of cycles. In Fig. 14, the number of Kaiser points at 80℃ is zero, while for granite at 50 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃, there are four, three, one, two, and four more Kaiser points, respectively, compared to granite at 80 ℃.

As temperature rises, the number of cyclic loadings during granite failure initially decreases, subsequently increases, and attains a minimum at 80 ℃ before rising once more. This behavior is due to the dependency of cyclic loading numbers on the peak strength of granite, with higher peak strengths resulting in more cycles. Similarly, the number of Kaiser points decreases initially and then increases with temperature, reaching a minimum at 80 ℃. This indicates that at 80 ℃, granite exhibits an extended crack compaction phase and fewer loading cycles, making Kaiser points difficult to accurately identify.

Damage and Kaiser effect of granite under cyclic loading-unloading conditions

Relationship between damage and kaiser effect

The Kaiser effect in rocks reflects the stress “memory capacity” of the rock through internal damage25. Analyzing the relationship between the Kaiser effect and damage characteristics contributes to the understanding of the mechanisms through which temperature affects the Kaiser effect in granite26. Based on experimental and numerical simulation results, the cumulative ringing count and fractured volume were used as indicators of damage intensity, while the average Felicity ratio was used to represent the Kaiser effect of granite27. The trends of damage intensity and Kaiser effect for granite under various temperatures during cyclic loading-unloading, as observed in physical experiments and numerical simulations, are shown in Fig. 15.

From Fig. 15(a), the cumulative ringing count of granite increases gradually with rising temperature, reaching a maximum of 9.2 × 106 times at 75 ℃, before sharply dropping to 1.5 × 106 times at 100 ℃. The Felicity ratio exhibits an opposite trend, decreasing continuously from 30 ℃ to 75 ℃ to a minimum of 0.4885 and then sharply increasing to 0.7782 at 100 ℃. Figure 15(b) illustrates that the trends observed in fractured volume and the average Felicity ratio obtained from numerical simulations mirror those from experimental results. The fractured volume of granite is 1.42 × 106 mm3 at 30 ℃ and increases initially as temperature rises, reaching a maximum of 3.3 × 106 mm3 at 80 ℃, before decreasing to 2.7 × 106mm3 at 100 ℃. The average Felicity ratio decreases from 0.986 at 30 ℃ to a minimum of 0.483 at 80 ℃, then rises to 0.758 at 100 ℃.

In laboratory experiments, the average Felicity ratio of granite at 75 ℃ is the lowest because this temperature corresponds to the highest cumulative acoustic emission ringing count, as shown in Fig. 6. Higher ringing counts indicate more severe damage, lower peak strength, and fewer loading cycles, resulting in the lowest number of Kaiser points and the lowest average Felicity ratio. Similarly, in numerical simulations, the lowest average Felicity ratio at 80 ℃ can be attributed to the largest fractured volume, confirming that the damage is most severe at this temperature. Figure 12 further shows that the peak strength and cyclic loading numbers at 80 ℃ are the lowest, leading to the lowest average Felicity ratio. This demonstrates the equivalence of identifying Kaiser points through fractured volume and cumulative ringing counts. It can thus be concluded that the temperature range of 70 ℃ to 90 ℃ represents the most severe damage and failure in granite.

Damage of granite under different temperatures during cyclic loading and unloading

The results from physical experiments and numerical simulations indicate that temperature significantly affects the severity of granite damage. The severity of this damage determines the Felicity ratio of granite. Consequently, it is possible to establish a functional relationship between the Felicity ratio and the damage variable associated with granite. Through this expression facilitates the prediction of the extent of damage to granite, enabling the assessment of whether it has reached the critical threshold of instability, which can help avert engineering-related accidents.

By analyzing the average Felicity ratio and fracture element volume curve in Fig. 15(b) using Origin software, the fitted curves exhibit the following relationship with temperature:

where F represents the average Felicity ratio of granite; T denotes the temperature of the granite specimen, in ℃; \({j_d}\) refers to the volume of the fractured unit at the point of granite instability failure, in mm³.

Continue to use the volume of the fractured unit to represent the damage variable of granite D.

where D represents the damage variable of granite; \({j_0}\) denotes the total volume of the granite specimen, in mm³, which is 196,349.54 mm³ for the standard cylindrical specimen.

Finally, combining Eq. (2) and Eq. (5), the relationship between the damage variable and the average Felicity ratio is established:

Using Eq. (6), the damage variable values of granite under different temperatures and varying cycles of loading and unloading are obtained, as shown in Figs. 16 and 17.

Analysis of Fig. 16: As the temperature rises, the damage variable of granite exhibits an initial increase followed by a subsequent decreases. The damage variables for granite at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 50 ℃, 55 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 75 ℃, 80 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃ are 0.123, 0.136, 0.148, 0.155, 0.172, 0.192, 0.243, 0.328, 0.285, and 0.211, respectively. The damage variable of granite at 80 ℃ is the highest, being greater than that of granite at 30 ℃, 40 ℃, 50 ℃, 55 ℃, 60 ℃, 70 ℃, 75 ℃, 90 ℃, and 100 ℃ by 62.5%, 58.5%, 54.9%, 52.7%, 47.6%, 41.5%, 25.9%, 13.1%, and 35.7%, respectively. This indicates that the damage severity of granite at 80 ℃ is the greatest, consistent with the changes in the fracture unit volume curve. Within the temperature range studied (30 ℃~100 ℃), granite exhibits the most severe damage at 80 ℃.

Analysis of Fig. 17: As the number of loading cycles increases, the damage variable of granite rises across all temperatures. Granite at 30℃ exhibits the smallest damage variable (0.123), while granite at 80 ℃ shows the largest (0.328). Consequently, under cyclic loading and unloading, granite at 80 ℃ suffers the highest degree of damage deterioration, which aligns with the finding presented in Sect. "Mechanical properties and Kaiser effect of granite at different temperatures". The above research indicates that the Felicity ratio effectively reflects the damage level of granite under cyclic loading and unloading at different temperatures, providing a reference for early warning of rock failure.

During the tunneling process, the damage or failure of the surrounding rock mass results in the most direct consequence: the collapse or instability of the surrounding rock. This occurs because, under the combined effects of internal stresses and external forces, the surrounding rock fails to maintain adequate structural stability, leading to localized or overall collapse. Additionally, rock mass damage may lead to secondary hazards such as rock bursts, gas emissions, or water-related disasters. This is particularly concerning under complex geological conditions, where dangerous substances like groundwater or gas may be present within rock fissures. Therefore, under cyclic loading and unloading conditions, the damage variable of granite can be calculated using the Felicity ratio through Eq. (6) for real-time monitoring, especially when the temperature of the granite reaches 80 °C. If a rapid increase in the calculated damage variable is detected, rapid support and reinforcement should be implemented to prevent further escalation of the damage, ensuring the safety of both personnel and equipment.

Discussion

The cumulative acoustic emission ring count of granite at various temperatures from physical experiments and the fractured element volume of granite at different temperatures from numerical simulations are shown in Fig. 18.

Analysis of Fig. 18shows that as temperature rises, the cumulative acoustic emission ring count observed in granite during experimental investigations exhibits an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease, with the maximum occurring at 75 ℃, indicating the most severe damage and destruction. Numerical simulations reveal that the cumulative fractured element volume of granite exhibits a comparable trend, peaking at 80 ℃. This is attributed to the increase and subsequent decrease in connected porosity of granite within the temperature range of 30 ℃ to 100 ℃, with the highest connected porosity observed at 80 ℃28, corresponding to the maximum damage extent. This suggests that under cyclic loading and unloading, granite exhibits a temperature damage threshold within the range of 80 ℃ to 90 ℃. Determining the precise threshold is the objective of future research.

Conclusions

-

1.

As temperature rises, the spacing density of stress-strain curves for granite under cyclic loading and unloading exhibits an initial decreases followed by an increase. The concavity of the compaction phase becomes more pronounced in granite specimens. As the number of cycles increases, the peak strength of granite specimens initially decreases and then increase, while the area of the plastic hysteresis loop initially increases and then decreases, with the largest hysteresis loop area observed at 75 ℃. At this temperature, stress memory significantly diminishes.

-

2.

As temperature rises, the cumulative acoustic emission (AE) ringing count produced during the entire failure process of granite initially increases and then decreases. The cumulative AE ringing count reaches its maximum at 75 ℃. The “friction-type” AE ringing counts generated in the early stages of cyclic loading and unloading hinder Kaiser point identification, whereas the “step-like” cumulative AE counts observed in the later stages of loading and unloading effectively facilitate Kaiser point identification.

-

3.

In the numerical simulation, The number of Kaiser points in granite specimens initially decreases and then increases as temperature rises, while the fracture unit volume initially increases and then decreases. Granite at 80 ℃ exhibits the fewest Kaiser points and the largest fracture unit volume.

-

4.

In the numerical simulation, As temperature rises and cyclic loading times increase, the damage variable of granite generally shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. The damage variable of granite at 30 ℃ is the smallest, while at 80 ℃ it is the largest. Granite exhibits a temperature damage threshold, which lies in the range of 80 ℃ to 90 ℃.

Data availability

Data Availability All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yu, Y., Wang, Z. & Wang, J. Study on acoustic emission characteristics of granite under incremental repeated loading and unloading. J. Beijing Jiaotong Univ. 46 (06), 123–131 (2022).

Zhao, K., Yang, D. & Huang, Z. Investigations and new insights on the relation between the valid interval of the Kaiser effect and the characteristic stress. Earth Sci. Rev. 249, 04673 (2024).

Wang, H., Ren, X. & Tao, R. Mechanism of rock deformation memory effect in low stress region based on frictional sliding. J. Cent. South. University(Science Technology). 43 (11), 4464–4471 (2012).

Tang, J. Experimental Study on the Effect of Stress Level and Holdup Time on Using Kaiser Effect and DRA Method to Measure Granite Prestress (Chongqing University, 2018).

Zhang, Y., Cao, L. & Li, Z. Experimental study on Kaiser effect characteristics of granite under different cyclic loading stresses. J. Experimental Mech. 36 (01), 123–132 (2021).

Sheng, M., Dao, X. & Peng, Y. Characteristics of Stress Memory and Acoustic Emission for Siltstone under different previous stresses. Int. J. Geomech. 24(3), 0402403 (2024).

Yan, Z. & Guan, C. O. J. S., Effect of loading rates on accurate in-situ stress determination in different lithologies via Kaiser effect. Arab. J. Geosci. 14, 14 (2021).

Tan, X. Research of Response Mechanism of Temperature Memory Effect on Rocks for Different Temperature Paths (Central South University, 2022).

Ge, Z. Research on high Temperature Physical Property Response and Thermal Damage Mechanism of Shale Thermally Assisted Development (Xi’an University of Science and Technology, 2022).

Fu, Y., Shi, C. & Ke, Z. Study on the mechanism of mechanical property strengthening of Beishan granite under mild temperature condition. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering. 40, 02554 (2022).

Ru, W., Shi, C. & Fu, Y. Experimental study on the Thermal Healing Effect on stress-damaged Granite. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56 (9), 6615–6629 (2023).

Hu, X., Ma, D. & Xie, N. An improved damage constitutive model for pre-heated rocks under uniaxial compression considering the initial compaction effect and residual strength. Int. J. Damage Mech. 34 (1), 52–80 (2025).

Tang, D. Study on Engineering Geology Properties and main problems of Yelei Hydropower Station Dam Foundation Extra-thick Overburden Q3. Des. Hydroelectric Power Stn. 25 (02), 87 (2009). Baotou: Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology.

Shi, M. Study on Mechanical Properties and Failure Characteristics of Granite under Temperature Stress (Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology, 2022).

Shi, X., Cai, W. & Meng, Y. Weakening laws of rock uniaxial compressive strength with consideration of water content and rock porosity. Arab. J. Geosci. 9, 5 (2016).

He, Z., Kun, L. & Wu, Z. Directional independence of the Kaiser effect of sandstone with high diameter–thickness ratios. Measurement. 196 (2022).

Gustavo, P., Amélia, D. & Ângela, L. Felicity ratio as a fingerprint of the thermal-induced decay on a Portuguese granite. J. Building Eng. 43, 103158 (2021).

Mohammadmahdi, D., Majid, N. & Kamran, G. Application of wavelet transform in evaluating the Kaiser effect of rocks in acoustic emission test. Measurement. 2022, 192. (2022).

Zhao, K., Liu, Y. & Yang, D. Fatigue mechanical properties and Kaiser effect characteristics of the saturated weakly cemented sandstone under different loading rate conditions. Eng. Geol. 41, 07732 (2024).

Choi, N., Kim, T. & Rhee, K. Kaiser effects in acoustic emission from composites during thermal cyclic-loading. NDT and E Int. 38 (4), 268–274 (2004).

Wang, C. Study on the Damage Evolution Law of Red Sandstone under Different Cyclic Loading and Unloading Paths (Shaoxing University of Arts and Sciences, 2021).

Qin, T. & Ren, K. Mechanical and acoustic emission characteristics of sandstone under cyclic loading and unloading. J. Heilongjiang Univ. Sci. Technol. 32(03), 275–279 (2022).

Lu, K., Zhang, W. & Xu, X. Kaiser effect of cracked sandstone under different loading rotating angles. Arab. J. Geosci. 4, 18 (2021).

Liu, W. Research on the Propagation Mechanism of Hydraulic Fractures in Heterogeneous Shale and the Optimization Method of Multi-fracture Balanced Propagation (Northeast Petroleum University, 2023).

Qing, M., Ming, Z. & Li, H. Acoustic Emission characteristics of red sandstone specimens under Uniaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51 (4), 969–988 (2018).

L N B., Studying the Kaiser Effect During Modeling of Rock Loading Conditions Using the NX-borehole Jack. Journal of Physics: Conference Series.1945(1): (2021).

Geofluids, B. E. Retracted: A Simple and Accurate Interpretation Method of In Situ Stress Measurement Based on Rock Kaiser Effect and Its Application. Geofluids. 2022. (2022).

Géraud, Y., Mazerolle, F. & Raynaud, S. Comparison between connected and overall porosity of thermally stressed granites. J. Struct. Geol. 14 (8–9), 981–990 (1992).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiankai Bao: Funding acquisition, Writing-Review and Editing, Resources. Shunjia Huang: Investigation, Writing-Original Draft. Yongjun Lv: Investigation. Yue Huang: Investigation, Resources. Lizhi Wang: Investigation, Resources. Xiaofan Zhang: Investigation, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, X., Huang, S., Lv, Y. et al. Study on Kaiser effect of granite under cyclic loading and unloading at different temperatures. Sci Rep 15, 11898 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90733-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90733-6