Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) and non-tuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) infections, both caused by acid-fast bacteria, exhibit overlapping clinical presentations and radiological findings, making accurate and swift differentiation imperative for appropriate patient management. The ability to promptly distinguish between TB and NTM is pivotal, particularly in healthcare settings where TB patients require isolation. So, there is a pressing need to identify reliable biomarkers capable of delineating these conditions. In this study, we carefully analyzed a group of 108 patients, including 38 with TB, 29 with NTM, and 41 with other respiratory diseases. We used bacterial 16 S rRNA sequencing to examine the relative amounts of different microbial species in each patient group. We also used advanced methods like co-occurrence analysis, mutually exclusive analysis, and decision tree analysis to explore the complex patterns within the microbial communities. Our investigation revealed intriguing associations between microbial taxa and disease entities. In TB patients, prominent species were Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus mutans, and Snodgrassella alvi, while in NTM, prominent species were Cariobacterium hominis and Prevotella nigrescens. The absence of Mobiluncus curtisii indicated a higher probability of NTM, especially if Olsenella phocaeensis was also absent. This comprehensive analysis unveiled distinct microbial signatures that serve as discerning markers for discriminating TB, NTM infections, and other respiratory ailments. By elucidating microbial patterns unique to each condition, our findings offer valuable insights into the development of diagnostic strategies and therapeutic interventions tailored to specific respiratory infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) and threatens human health. Rapid and accurate diagnosis of TB enables isolation and appropriate treatment of patients with respiratory diseases1. TB is diagnosed by detecting M. tuberculosis using the existing acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear technique. However, due to its low sensitivity, there is a high possibility of misdiagnosis. Bacterial culture is a classic method for detecting M. tuberculosis, but it takes up to 2 months to confirm2. Because it takes a long time to make an accurate diagnosis, it is not conducive to TB control because it can be transmitted by TB patients who have not been isolated before diagnosis. Although TB PCR and Gene Xpert techniques have improved diagnostic accuracy and shortened the diagnostic process3, there remains an unmet need for diagnosing TB in patients with a low bacterial burden4. It is clear that we need additional methods to enhance TB diagnosis. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are acid-fast organisms not caused by M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae5. Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate therapies and complications, given that treatment regimens and disease progression differ significantly between the two6. In the case of NTM patients, symptoms and radiological examination results are like those of TB. However, isolation is not required because it is known that the ability of person-to-person transmission of NTM is very low7. Therefore, it is essential to provide an early differential diagnosis of NTM and TB for better treatment and especially for the decision of isolation.

Many specimens are targeted in the search for better methods to achieve the differential diagnosis of TB and NTM. Other than blood or urine, and offering greater precision than sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) is utilized as a sterile specimen to detect pathogens causing respiratory infections8. BALF is a superior and more accurate specimen for diagnosing mycobacterial diseases because it directly reflects the site of disease pathogenesis. BALF has been utilized as a major factor for the diagnosis of TB or NTM. The BALF metagenome research is crucial because it provides a comprehensive understanding of the microbial composition present. BALF metagenome analysis enables the identification of co-existing microbiomes, which are common in TB or NTM cases and can differential diagnosis and treatment9. Understanding the microbial diversity and functional potential within these infections also sheds light on host-pathogen interactions, contributing to our understanding of disease pathogenesis9,10. Attempts were made for a diagnostic tool of TB based on the microbiome patterns found in BALF, but more samples needed to be analyzed for classification, and there have been no studies related to NTM11,12. Thus, in this study, we tried integrating causative factors using metagenomic analysis in BALF samples from TB and NTM.

LefSe (Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size) analysis is an algorithm used to identify differences in microbial distribution between groups and to determine whether these differences are statistically significant. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) can be used to quantitatively evaluate the effect of each microbial species on the differences between groups, which can be represented as a barplot. The larger the LDA values, the greater the contribution of that species to the differences between groups. Decision Tree is an algorithm that classifies or predicts data in a tree shape, asks questions about each variable, and presents and visualizes conclusions that fit the conditions. It is also used to discover biomarkers that suggest whether microbial distribution is present in a specific group. We performed microbiome analysis on patients with TB, NTM, and afflicted with various other respiratory diseases. LefSe and Decision tree analysis were performed to classify each patient group.

Results

Patient information

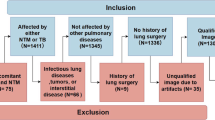

Table 1 shows the baseline information for 38 patients with TB, 29 NTM, and 41 others. Mean age of three category patients were early 60s. Other comorbidities and symptoms presented were described in the Table 1. Age and BMI did not differ significantly among the three groups, and the proportion of women was higher in NTM. Among the three groups, the proportion of smoking and alcohol drinking was higher in TB. The proportion of hypertension was similar among the three groups, and the proportion of diabetes was highest in TB.

Microbiome landscape of three groups

The overall microbiome distribution (phylum level) by metagenome analysis of TB, NTM, and others is shown in the figure (Fig. 1A). The dominant species in all three groups were Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria were prominently observed. In most patients, the most dominant species was Firmicutes, but in only five patients the most dominant species was Actinobacteria. In one patient, the most dominant species was Actinobacteria, followed by Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria. LefSe was used to visualize the microbiome frequently seen in each group of TB, NTM, and others. Bifidobacterium, Snodgrassella alvi, Hyphomicrobiales, and Enterococcus faecalis were mainly found in TB patients. In contrast, Cariobacterium hominis, Staphylococcus, Peptidiphaga gingivicola, Capnocytophaga, and Flavobacteriaceae were frequently found in patients with NTM lung disease (Fig. 1B). In the left circos plot of LefSe, out of a total of 14 taxa, one taxon each from NTM and TB was presented at the order level. At the family level, three taxa were presented only from NTM, and at the genus level, four, three, and two taxa were presented from NTM, Others, and TB, respectively. Taxa displayed in the right barplot of LDA score included three, four, and two taxa at the species level from NTM, Others, and TB, respectively. So, total 11, seven, and five taxa were indicated.

Distinct patterns by three groups

Using heatmaps, we represented strains specifically found in TB, NTM, and others at the species and genus levels. From the ANOVA analysis for the three groups, 10 species and nine genera were presented with p-value < 0.05. If found, the cells are marked in pink; if not, they are marked in yellow (Fig. 2A).

(A) Heatmap of abundance in genus and species levels. (B) Co-occurrence and mutually exclusive detection patterns of 10 species in TB, NTM, others, and all samples. (C) Proportion of three groups. (D) The values for TB, NTM, and others for each of the five diversity indices are presented as boxplots. The mean and median of each value are indicated by dots and horizontal lines. (E) The principal component analysis (PCA) results are visualized, and the dimensionality reduction results corresponding to PC1 and PC2 are presented on the x and y axes, respectively.

We conducted network analysis for ten strains shown in the heatmap at the species level. A total of four network analyses were performed, and co-occurrence and mutually exclusive patterns in the 108 total patients, TB (n = 38), NTM (n = 29), and others (n = 41) samples were visualized from left to right. If the color of each node is the same, it indicates inclusion in the same phylum. Four phylums were observed, and each node was indicated with a color key. A red line represents co-occurrence, while a green line indicates strains that are mutually exclusive in abundance. A solid line indicates high statistical significance (p-value < 0.05), and a dotted line means no statistical significance (p-value > = 0.05) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2C summarizes the microbiomes that show differences among the three groups at the species level. In TB patients, prominent species were Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus mutans, and Snodgrassella alvi, while in NTM, prominent microbes were Cariobacterium hominis and Prevotella nigrescens. Alpha diversity was presented as a boxplot in the form of five indices, observed operational taxonomic unit (OTU), Chao1, Shannon, GiniSimpson, and GoodsCoverge. Each diversity value was presented as a boxplot, and the mean and median of each group were presented as points and horizontal lines, and no critical difference was found among the three groups (Fig. 2D). Dimensionality reduction was performed on the abundance of each taxon in the form of principal component analysis (PCA) and visualized (Fig. 2E).

To confirm the diagnostic role in distinguishing TB, NTM, and others, we conducted machine learning at the species level to differentiate the three groups based solely on the microbiome. The presence of Enterococcus faecalis indicated a higher likelihood of TB. In comparison, the absence of Mobiluncus curtisii and the presence of Cardiobacterium hominis indicated a higher probability of NTM, especially if Olsenella phocaeensis was also absent (Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study explored the intricate landscape of the microbiome present in BAL samples collected from patients undergoing evaluation for suspected TB as their initial presentation of respiratory illness, alongside individuals presenting with other respiratory conditions. By analysis, we revealed substantial disparities in BAL microbiomes among three distinct patient cohorts. Those three cohorts consist of diagnosed with TB, NTM, and afflicted with various other respiratory diseases.

Within the subset of TB patients, a notable prevalence of specific microbiomes emerged, notably including Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus mutans, and Snodgrassella alvi. Conversely, in individuals diagnosed with NTM infections, distinct species of interest included Cariobacterium hominis and Prevotella nigrescens, the latter exhibiting a noteworthy co-occurrence pattern. Employing advanced machine learning techniques, we identified Enterococcus faecalis as the primary species significantly abundant in TB cases, while the absence of Mobiliuncus curtisii and the presence of Cariobacterium hominis emerged as pivotal factors facilitating the diagnosis of NTM infections.

In terms of the correlation between TB and Enterococcus, in previous research, the association between the gut microbiome Enterococcus and TB was demonstrated, showing that Enterococcuscan modulate TB expression13. Within the gastrointestinal tract, the secretions of Enterococcus bacteria can influence tuberculosis expression, revealing a possible anti-TB effect and suggesting protective benefits for humans14. Although Enterococcus faecalisis a common bacterium in the human gut, it can become pathogenic in other organs, including the respiratory tract, in individuals with weakened immune systems15. There are no previous studies that explain the co-occurrence of TB and Enterococcus. However, our study revealed that the abundance of the Enterococcus faecalis could be correlated to the microbiome environment in TB patients.

For NTM patients, we could find a correlation with oral microbiomes, including Provotella nigrescens. A previous study examined the NTM microbiome found that oral microbiota such as Prevotella and Veillonellawere significantly present in BAL fluid16, not just in oral secretions or sputum. This presence is linked to increased inflammation17. The study suggests that microaspiration of the oral cavity microbiome may lead to changes in the microbiota of the lower respiratory tract, potentially affecting the host immune phenotype of the airway mucosa15,18. The lungs selectively eliminate Prevotellabacteria from the upper airways, a process not seen in the stomach19. Subclinical lung inflammation might foster an environment conducive to retaining Prevotellain the lungs20,21.

Conversely, the presence of Prevotellacould induce subclinical lung inflammation, a hypothesis suggested by Larsen and colleagues20,22. This interaction highlights a complex relationship between lung microbiota and inflammation. Similarly, COVID-19 and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis metagenomic studies have identified that anaerobic bacteria like Prevotellacan colonize the lungs, disrupting homeostasis and potentially causing chronic and acute severe symptoms23,24.

In this study, over half of the patients with NTM infections showed the presence of Cardiobacterium in their microbiome, suggesting a strong association with NTM development and growth. This is the first time such a connection has been demonstrated. Cardiobacterium species, resembling Pasteurella, are commonly found in the microbiota of the nose, mouth, throat, and occasionally in the gastrointestinal tract25. The frequent occurrence of gut microbiota in these patients, considering factors like gastroesophageal reflux disease or aspiration from drinking water in NTM pathogenesis, suggests that these gastrointestinal tract bacteria might migrate to the lungs in immunocompromised NTM patients, thereby altering the lung microbiome.

When we look at the correlation of each microbiome, Cardiobacterium co-occurred with Prevotella nigrens but was counter to Mobiluncus curtisii. Cardiobacterium and Prevotellaare notably problematic in immunocompromised patients, like NTM infections21. These bacteria, which usually don’t dominate the lower respiratory tract in healthy individuals, appear to become prevalent in NTM patients with weakened immune systems. In NTM, protective bacteria like Lawsonibacter asaccharolyticus, Alistipes finegoldii, and Snodgrassella alvi were notably absent. Snodgrassella alviis known for its potential beneficial effects on gut health and immune function15. The scarcity of such protective microbiota in NTM cases suggests that their absence could contribute to the progression of NTM infections.

Although this study is not clinically applicable at present, it has certain strengths that could have future clinical implications. First, the co-detection of Enterococcus faecalis may provide additional diagnostic value for TB, while Cardiobacterium or Prevotella could serve as supplementary tools for diagnosing NTM. Second, protective bacteria such as Lawsonibacter asaccharolyticus, Alistipes finegoldii, and Snodgrassella alvi could be potential targets for the treatment of NTM.

However, this study also has several limitations. First, there is a possibility of contamination from upper respiratory samples. Additionally, there could be heterogeneity in the samples, as a single sample may not represent the entire microbial community. Nonetheless, BALF is a more targeted sample, so contamination is likely to be much lower compared to sputum, making BALF more suitable for metagenomic studies. Second, biases inherent in metagenomic analysis, such as DNA extraction bias, could affect the results. However, we optimized DNA extraction protocols to target a broad range of organisms. Third, there could be algorithmic limitations affecting the accuracy of machine learning models and bioinformatics biases related to taxonomic resolution or read assembly.

In conclusion, our study illuminates the intricate and nuanced microbiome patterns that can serve as discriminatory markers for differentiating between diseases such as TB and NTM infections, even when the predominant lung microbiome is not directly involved. Enterococcus might have a relation with pathogenesis of TB. Also, bacteria such as Cardiobacterium and Prevotella with NTM infections underscore their potential roles in dictating disease progression trajectories. Moreover, the conspicuous absence of protective microbiota like Lawsonibacter asaccharolyticus, Alistipes finegoldii, and Snodgrassella alvi in NTM cases underscores their putative contributory role in facilitating NTM infection progression. Further diagnostic or therapeutic endeavors may stand to gain substantial insights and efficacy through validation via sophisticated methodologies such as shotgun sequencing, thus paving the path toward more precise and personalized management strategies for these complex respiratory conditions.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Korea University Guro Hospital (2017GR0012). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. Informed consent was obtained after a thorough explanation of the study’s objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participants were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without any impact on their current or future care. Confidentiality and anonymity of the participants were maintained throughout the study. All patients were selected by the Pulmonology Department at the Korea University Guro Hospital to undergo fiberoptic bronchoscopy and BALF collection for diagnostic purposes. BALF was collected as a standard protocol8,26. BALF was collected by inserting a bronchoscope, instilling 30 to 50 mL of sterile saline into the bronchial segment, and then aspirating the fluid using low negative pressure to minimize trauma. The procedure is conducted under sedation, and the fluid is collected into sterile containers with gentle suction, while monitoring for any complications. Patients who had a peripheral arterial pulse oximetry value (SpO2) less than 90% in room air setting were excluded in this study. Subjects with tracheostomy, requiring home oxygen therapy or mechanical or noninvasive ventilation, nasal or nasopharyngeal disease, not able to express themselves clearly, and pregnant individuals were excluded from the study. 16 S metagenomics sequencing was performed on 108 samples, and the demographic and basal characteristics of the enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1.

Metagenomic analysis: 16 S rRNA and its diversity

From BALF, DNA was extracted by DNeasyPowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s manuals. The extracted DNA was quantified using Quant-IT PicoGreen (Invitrogen). The sequencing libraries were prepared by the Illumina 16 S Metagenomic Sequencing Library protocols to amplify the V3 and V4 regions. Paired-end (2 × 300 bp) sequencing was performed using the MiSeq™ platform (Illumina). We processed the FASTQ files using FastQC to perform quality control of the raw sequences. The raw 16 S amplicon sequences were processed by QIIME2 v1.8.0 with default parameters27. We then used SHI7 for trimming Nextera adapters and stitching paired-end reads and performed quality trimming at both ends of the stitched reads until a minimum Phred score of 32 was reached28. These merged and filtered reads were used for closed-reference OTU picking, and the OTUs were determined by de novoclustering of the sequences with a 97% sequence identity cut-off by QIIME. We performed alpha- and beta-diversity analyses in R using the vegan and phyloseq packages29. Based on the OTU table, we calculated the average richness estimate for each alpha-diversity metric (Chao1, observed OTUs, and Shannon). To confirm the species diversity and uniformity of microbial communities in each sample, Shannon Index and Inversed Simpson Index were obtained. Alpha diversity information was confirmed by the Rarefaction curve and the Chao1 value. The beta diversity between samples was visualized by PCA, and we used three default R function, “prcomp”, “plot” and “legend” functions to perform PCA and its visualization.

Visualize abundance of microbiomes

We obtained the abundance corresponding to each taxon in the form of a dataframe in R. We excluded M. tuberculosis, known to cause TB, from the species level within Mycobacterium. To visualize the distribution of the microbiome, we used the ggplot2 package in R for a proportional barplot. We utilized LefSe to discover a taxon that stands out prominently between each group30. To run LefSe, we connected to Galaxy LefSe (http://galaxy.biobakery.org/) and uploaded the microbiome data after modifying it to fit the LefSe input format. All parameters used default values, and the generated figure was exported. For boxplot visualization, R “ggboxplot “function was used. For visualizing each abundance as a heatmap, we used the pheatmap package. To build a model distinguishing the three groups, we used the rpart package and the rpart.plot for visualization.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are accessible through GEO accession number GSE278953. Any questions regarding the data should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

Nahid, P., Pai, M. & C. Hopewell, P. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 3, 103–110 (2006).

Huang, Y., Ai, L., Wang, X., Sun, Z. & Wang, F. Review and updates on the diagnosis of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11195826 (2022).

Steingart, K. R. et al. Xpert® MTB/RIF assay for pulmonary tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009593.pub3 (2014).

The Lancet, M. The unsustainable anachronism of tuberculosis diagnosis. Lancet Microbe. 4, e379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00153-2 (2023).

To, K., Cao, R., Yegiazaryan, A., Owens, J. & Venketaraman, V. General Overview of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Opportunistic Pathogens: Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium abscessus. J. Clin. Med. 9 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9082541 (2020).

Gopalaswamy, R., Shanmugam, S., Mondal, R. & Subbian, S. Of tuberculosis and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections – a comparative analysis of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. J. Biomed. Sci. 27, 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-020-00667-6 (2020).

Chin, K. L., Sarmiento, M. E., Alvarez-Cabrera, N., Norazmi, M. N. & Acosta, A. Pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections: current state and future management. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39, 799–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03771-0 (2020).

Davidson, K. R., Ha, D. M., Schwarz, M. I. & Chan, E. D. Bronchoalveolar lavage as a diagnostic procedure: a review of known cellular and molecular findings in various lung diseases. J. Thorac. Dis. 12, 4991–5019. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-651 (2020).

Xiao, G. et al. Insights into the Unique Lung Microbiota Profile of Pulmonary Tuberculosis patients using Metagenomic Next-Generation sequencing. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0190121. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01901-21 (2022).

Wolak, J. E., Esther, C. R. Jr & O’Connell, T. M. Metabolomic analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from cystic fibrosis patients. Biomarkers 14, 55–60 (2009).

Liu, X. et al. Indicators for prediction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis positivity detected with bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-018-0403-x (2018).

Wang, J., Xu, H., Wang, X. & Lan, J. Rapid diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary diseases by metagenomic next-generation sequencing in non-referral hospitals. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 1083497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.1083497 (2022).

Fellag, M. et al. Culturomics discloses Anti-tubercular Enterococci Exclusive of Pulmonary Tuberculosis: a preliminary Report. Microorganisms 8 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8101544 (2020).

Achache, W., Mege, J. L., Fellag, M. & Drancourt, M. The Enterococcus secretome inhibits the growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex mycobacteria. Access. Microbiol. 5 https://doi.org/10.1099/acmi.0.000471.v3 (2023).

Zafar, H. & Saier, M. H. Understanding the relationship of the human bacteriome with COVID-19 severity and recovery. Cells 12, 1213 (2023).

Sulaiman, I. et al. Evaluation of the airway microbiome in nontuberculous mycobacteria disease. Eur. Respir J. 52 https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00810-2018 (2018).

Segal, L. N. et al. Enrichment of lung microbiome with supraglottic taxa is associated with increased pulmonary inflammation. Microbiome 1 https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-2618-1-19 (2013).

Dickson, R. P. et al. Cell-associated bacteria in the human lung microbiome. Microbiome 2, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-2618-2-28 (2014).

Bassis, C. M. et al. Analysis of the upper respiratory tract microbiotas as the source of the lung and gastric microbiotas in healthy individuals. mBio 6, e00037. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00037-15 (2015).

Larsen, J. M. et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma-associated Proteobacteria, but not commensal Prevotella spp., promote toll-like receptor 2-independent lung inflammation and pathology. Immunology 144, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12376 (2015).

Larsen, J. M. The immune response to Prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology 151, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/imm.12760 (2017).

Larsen, J. M. et al. Divergent pro-inflammatory profile of human dendritic cells in response to commensal and pathogenic bacteria associated with the airway microbiota. PLoS One. 7, e31976. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031976 (2012).

Chakraborty, S. et al. SARS-Cov2 enables anaerobic bacteria (Prevotella, to colonize the lungs disrupting homeostasis, causing long-drawn chronic symptoms, and acute severe symptoms (ARDS, septic shock, clots, arterial stroke) which finds resonance, with key differences, in the ‘forgotten disease’Lemierre Syndrome, enabled by Epstein Barr Virus. Open Science Framework (2020).

Rogers, G. B. et al. Clinical measures of disease in adult non-CF bronchiectasis correlate with airway microbiota composition. Thorax 68, 731–737. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203105 (2013).

Steinberg, J. P. & Burd, E. M. Other gram-negative and gram-variable bacilli. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases, 3015–3033 (2010).

Bhargava, M. et al. Proteome Profiling in Lung Injury after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 22, 1383–1390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.04.021 (2016).

Hall, M. & Beiko, R. G. 16S rRNA gene analysis with QIIME2. Methods Mol. Biol. 1849, 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8728-3_8 (2018).

Al-Ghalith, G. A., Hillmann, B., Ang, K., Shields-Cutler, R. & Knights, D. SHI7 is a Self-Learning Pipeline for Multipurpose Short-Read DNA Quality Control. mSystems 3 https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00202-17 (2018).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 8, e61217. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217 (2013).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1C1C1009250).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2022R1C1C1009250).

Institutional Review Board Statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea University Guro Hospital (approval number: 2017GR0012) and was performed by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y.O., Y.K.K., J.-A.G.; methodology, J.Y.O. and J.-A.G.; formal analysis, J.Y.O., Y.K.K., M.H.J., H.M.D.; investigation, Y.K.K., M.H.J., H.M.D.; resources, J.Y.O., Y.K.K., M.H.J.; data curation, J.Y.O., Y.K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.O., Y.K.K., J.-A.G.; writing—review and editing, M.H.J., H.M.D., S.R.; visualization, S.R., and J.-A.G.; supervision, J.Y.O.; project administration, J.-A.G.; funding acquisition, J.Y.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oh, J.Y., Ko, Y.K., Jeon, M.H. et al. Distinguishing tuberculosis from non-tuberculous mycobacteria and other respiratory conditions by microbiome patterns. Sci Rep 15, 36129 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90776-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90776-9