Abstract

As network intrusion behaviors become increasingly complex, traditional intrusion detection systems face limitations, especially with data imbalance. To address this, we introduce the Nash equilibrium concept from game theory into classifier ensemble optimization, enhancing robustness in multi-class classification tasks. Additionally, we propose a network intrusion detection system based on a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network with Conditional Aggregation Encoder-Decoder Structure (CE-GAN) with a conditional aggregation encoder-decoder structure to mitigate data imbalance and improve classifier performance. The model incorporates a composite loss function to maintain both the authenticity and diversity of generated samples. Experiments on the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets show that CE-GAN effectively augments rare data samples, significantly improving classification metrics for imbalanced datasets, thus providing a superior solution to this challenge in network intrusion detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development and widespread adoption of the Internet, network security issues have become increasingly prominent1. Network intrusion detection systems (IDS) play a critical role in safeguarding systems from attacks that threaten integrity, confidentiality, and availability2. However, traditional IDS methods struggle with the imbalance between normal and anomalous traffic in real-world data. This imbalance leads to poor detection of minority class attack samples, resulting in increased false negatives and false alarms, which limits the effectiveness of IDS in practical applications.3

In recent years, researchers have proposed various GAN-based methods to address the data imbalance issue in Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS)4,5. Gwo-Chuan Lee et al.6introduced a model based on Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) to tackle data imbalance through data augmentation, improving the recognition accuracy of rare attack types. The gradient penalty method enhances training stability and convergence, but the two-stage fine-tuning algorithm increases system complexity and computational cost, with a high dependency on data quality. Zecheng Li et al.7 proposed a GAN-based denoising autoencoder model, which improves semi-supervised anomaly detection models by using pseudo-anomalous data for data augmentation and feature extraction. However, this approach demands significant computational resources and incurs high costs when processing high-dimensional data. Kunda Suresh Babu et al.8 developed an improved conditional GAN combined with Bi-LSTM for multi-class intrusion detection by generating minority class samples to balance datasets. Although this combination improves detection performance, it introduces complexity and relies heavily on data quality and diversity. Similarly, NAIBO ZHU et al.9 introduced an auxiliary GAN-based network intrusion detection strategy, which addresses class imbalance by incorporating class signals into the GAN architecture. While this enhances classification performance for minority classes, maintaining recognition capability for emerging attack behaviors requires continual optimization.

Additionally, Alper Sarıkaya et al.10 proposed a hybrid model combining LightGBM for feature selection and GRU for attack classification, solving the class imbalance problem in NIDS. They introduced an innovative “threshold method” that determines the optimal feature subset by gradually removing unimportant features based on LightGBM’s feature importance function. However, this method focuses primarily on individual feature importance, neglecting potential interactions between features. Hoang V. Vo et al.11 developed a real-time intrusion detection method based on enhanced WGAN and parallel ensemble learning (APELID), improving WGAN’s ability to generate realistic minority class samples and using parallel ensemble learning models to boost detection performance. APELID combines various complex algorithms, such as WGAN, clustering algorithms, parallel ensemble learning models, and sandbox analyzers, increasing system complexity. Xu Liu et al.12 proposed a network anomaly detection scheme based on feature representation and data augmentation. By employing a pixel rearrangement strategy, network traffic features were successfully transformed into images while maintaining spatial relationships between features, aiding deep learning models in capturing higher-order features. However, in high-dimensional feature spaces, it may not capture all critical feature interactions, affecting the comprehensiveness of feature representation. Cheolhee Park et al.13 introduced a GAN-based enhanced NIDS, aiming to address data imbalance and improve detection performance. By using an autoencoder as a feature extractor, the data dimensionality is effectively reduced while retaining essential feature information, improving classifier performance. However, overlapping feature characteristics among certain attack categories might prevent the generative model from fully distinguishing between different categories, impacting the detection accuracy of minority classes.

These studies demonstrate that using GANs for data augmentation shows great potential for addressing data imbalance in NIDS. However, as network attack methods evolve, continual optimization and innovation in GAN models are necessary to enhance their ability to detect new types of attacks.

All of the aforementioned studies have made significant progress in their research, but there are still some issues that need to be addressed.14

-

1.

Existing classification algorithms, being single-method approaches, face limitations in multi-class tasks. When dealing with imbalanced data distribution, the overall classification metrics may appear satisfactory, but the minority classes are not effectively detected, resulting in poor performance. This leads to artificially inflated metrics for the classification algorithm.15

-

2.

Existing data augmentation algorithms mainly rely on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). However, these algorithms lack effective conditional constraints during the training process, which leads to imbalanced generation results, further exacerbating the issue of data imbalance during augmentation.

-

3.

Most existing algorithms use simple loss strategies to guide model training. However, for complex Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), more sophisticated loss strategies are often needed to constrain the generator, ensuring the quality of the generated results while simultaneously accelerating the training process.

-

4.

Current Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) algorithms typically use relatively simple network structures to train the generator. However, for complex network attack tasks, this approach struggles to capture deep features. The model requires a more concise data representation method to facilitate feature learning and model training.

Our work

-

1.

To address the limitations of single classification algorithms in handling multi-class classification tasks with poor performance metrics, the concept of Nash equilibrium from game theory is introduced. This enables the optimal strategy combination of classifiers, collectively improving overall performance. By optimizing the classification algorithm’s ability to detect minority class attack samples, this approach effectively mitigates the data imbalance issue and resolves the problem of artificially inflated classification metrics.

-

2.

To address the issue of data imbalance that persists in existing data augmentation algorithms, a Conditional Generative Adversarial Network (CGAN) is introduced. By applying conditional constraints, this approach ensures both the balance and diversity of the generated results, effectively solving the problem of inflated classification metrics caused by data imbalance.

-

3.

To address the limitations of existing simple loss strategies, a composite loss strategy is introduced to guide the training of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). This strategy constrains the generator’s training from multiple dimensions, ensuring the quality of the generated results while simultaneously speeding up the model’s training process.

-

4.

To address the difficulty Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) face in learning superficial features, we propose a conditional constraint-based encoding representation method. This approach facilitates the training of imbalanced data by ensuring the model learns deep features while addressing typical issues with conventional encoding methods.

Dataset description

The NSL-KDD dataset is an important dataset in Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS) research, primarily used in the field of network attacks16,17. As shown in Table 1, the dataset contains a total of 41 network traffic features along with corresponding attack types and their significance. This dataset covers the key characteristics of network traffic, facilitating the analysis of the relationship between feature importance and attack types. The features are mainly divided into four categories: basic features, content features, time-based features, and traffic features.

The NSL-KDD dataset is an improved version of the KDD Cup 99 dataset, addressing the issues of redundant records and data imbalance present in the original version. The dataset contains a total of 125,973 network attack records, with 67,343 normal records and 58,630 abnormal records. The abnormal portion consists of 23 types of attacks. As shown in Fig. 1, while the proportion of normal and abnormal records appears balanced, a more detailed breakdown of the abnormal records reveals severe imbalance across the different subcategories. Some attack types are significantly underrepresented, leading to persistent imbalance in multi-class tasks within the NSL-KDD dataset, which in turn causes inflated performance metrics.

The UNSW-NB15 dataset was created by the Cybersecurity Research Team at the University of New South Wales, Australia, with the aim of simulating various network traffic types in modern network environments, particularly for research in Network Intrusion Detection Systems (NIDS)18. This dataset was generated in a cybersecurity laboratory and includes both normal and attack data, providing researchers and developers a tool to evaluate and improve intrusion detection algorithms. The dataset consists of 175,341 training records and 82,332 test records, totaling 257,673 network traffic records. Each record is composed of 49 features, which are divided into five categories: flow features, basic features, content features, time-based features, and generated features. As shown in Fig. 2, its main characteristics are similar to those of the NSL-KDD dataset, both exhibiting an imbalance in the proportion of abnormal traffic. This study will focus on addressing the data imbalance issues in both the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets to resolve the problem of inflated performance metrics in classification algorithms.

Nash equilibrium-based classifiers

In network intrusion detection, the performance of classifiers is critical to the overall accuracy and reliability of the system. As time progresses, network attacks become increasingly diverse and complex, and a single classifier inevitably faces limitations in multi-class tasks. As shown in Table 2, we list three mature and excellent classification algorithms-DecisionTreeClassifier, ExtraTreesClassifier, and GradientBoostingClassifier. The classification results are quantified using common metrics in classification tasks, as displayed in the Table 2. The results show that all three algorithms perform well in overall metrics, effectively distinguishing between normal and abnormal samples. However, when it comes to multi-class classification, the performance of all three classifiers is less satisfactory. Specifically, when dealing with rare samples, the performance of these algorithms varies significantly, highlighting their limitations.

To overcome the aforementioned limitations, we introduced the concept of Nash equilibrium from game theory. By employing an ensemble learning approach, we optimized the combination strategies of multiple classifiers to enhance their robustness and performance when dealing with imbalanced data. Our research focuses on ensuring that classifiers remain stable and efficient despite changes in initial weights, thereby improving the overall system performance. The classifier structure is shown in Fig. 3.

At the start of training,three classifiers are initialized: the Random Forest Classifier, the Extra Trees Classifier, and the Gradient Boosting Classifier. The initial weights for each classifier are as follows: \(w_i\), satisfy \(w_1+w_2+w_3=1\).For each classifier, the error rate is calculated. Assume the error rates for each classifier are as follows: \(error_k\) , \(k \in \left\{ rf, et, gb\right\}\), The error rate formula is as follows:

Here, \(x_i\) represents the feature vector of the i-th sample, \(y_i\) represents the true label of the i -th sample. \(\textrm{II}\) is an indicator function,When the classifier’s prediction \(M_1\) for sample \(x_i\) differs from the true label \(y_i\) ,the value of \(\textrm{II}\) is 1,otherwise, it is 0. The payoff for each classifier is calculated based on its error rate, where a lower error rate results in a higher payoff. The payoff formula is as follows:

The weights of the three classifiers are defined as follows \(w_1,w_2,w_3\) .The weights are adjusted based on the payoff of each classifier. The weight update formula is as follows:

\(w _ { i } ^ { ( t ) }\)represents the weight of the i-th classifier at the t-th iteration, \(p a y o f f _ { k } ^ { ( t ) }\) represents the payoff of the i-th classifier at the t-th iteration. Repeat the steps of calculating error rate, payoff, and updating the strategy until the change in weights is smaller than a small threshold \(\epsilon\) ,indicating that Nash equilibrium has been reached:

After reaching Nash equilibrium, the final prediction result is the weighted average of the predictions from each classifier:

Here, \(w _ {rf} ^ { * },w _ {et} ^ { * },w _ {gb} ^ { * }\) represents the optimal weight of the i -th classifier in the Nash equilibrium state.

To better demonstrate the performance advantages of our proposed classifier, we compared its performance on the KDDTrain+ and KDDTest+ datasets. As shown in Table 3 , our optimization strategy outperforms traditional single classifiers in classification tasks, particularly in the recognition of rare samples, where it exhibits significant performance improvement. This further proves the effectiveness and practicality of optimizing classifier combinations using game theory strategies.

Furthermore, we have listed the various metrics for the multi-class tasks in ensemble learning, as shown in Table 4. The overall accuracy of the model reaches 99.62%, which is excellent compared to similar fields. However, when specifically distinguishing each subclass, the classification performance for smaller categories is significantly lower. Categories such as rootkit, bufferoverflow, imap, land, loadmodule, and perl, due to the limited representation in the dataset, result in very low classification metrics, or even complete failure to detect them. In network attack simulations, the failure to detect any type of attack can potentially lead to serious consequences.

Additionally, due to the impact of the extremely small representation of certain categories, the performance metrics for these classes fluctuate significantly. Take loadmodule as an example: since there is only one instance recorded in the dataset, the test accuracy for this category can only be 0 Therefore, when evaluating classification models using datasets, the overall evaluation metrics are not suitable for describing rare samples. Instead, data augmentation algorithms are needed to expand the number of rare samples, allowing the model’s performance to be evaluated across a larger, more balanced sample size. In this case, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) become the best tool for data augmentation. Through the adversarial training between the generator and discriminator networks, the generator is able to create realistic data samples, effectively compensating for the lack of rare class samples in the dataset. This approach not only increases the number of rare samples but also preserves the diversity of the samples, making the classification model’s performance on minority classes more stable and reliable. By introducing GANs, we can significantly expand the number of rare samples without altering the structure of the original dataset, resulting in more representative performance metrics when evaluating classification models. Additionally, GAN-generated samples retain the key features of the original data, avoiding the risk of model overfitting that can occur with simple duplication or excessive augmentation. Therefore, the application of GANs not only overcomes the limitations of traditional data augmentation methods but also lays a solid foundation for further improving the generalization ability of classification models.

Conditional-based generative adversarial network

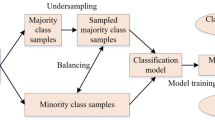

Based on the distribution analysis of the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets and the limitations of classification algorithms, this study utilizes a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) as the primary method to augment the minority class samples in both datasets. The process flow is illustrated in Fig. 4. After normalizing the dataset, it is divided into majority and minority classes. The minority class samples, along with normal samples, are input into the GAN to generate new samples. Once validated, these new samples are merged with the majority class, completing the dataset augmentation. The augmented dataset is then fed into the classification algorithm, and if the classification performance improves, it demonstrates the effectiveness of the GAN algorithm proposed in this study.

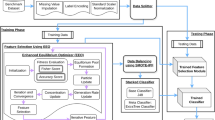

Traditional machine learning and deep learning models rely on large amounts of high-quality, balanced data for training. Therefore, while performing data augmentation, it is crucial to ensure that the augmented data does not reintroduce imbalance. Additionally, network traffic data is characterized by high complexity and diversity, which makes it challenging for Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to capture surface-level features. To address this, a dimensionality reduction encoding method is required, combined with conditional constraints to distinguish between normal and anomalous data. As illustrated in Fig. 5, we propose a CE-GAN, which integrates conditional encoding. This model comprises four networks: Encoder, Decoder, Generator, and Discriminator. The Encoder and Decoder are responsible for converting between high- and low-dimensional feature data, while leveraging data condition types to further distinguish between normal and anomalous samples. This helps to mitigate the potential impact of data imbalance from the input stage. The Encoder reduces the data’s dimensionality, while the Decoder remaps the data back into high-dimensional space. The Generator and Discriminator are mainly responsible for generating and evaluating data: the Generator produces data samples that meet specific conditions, and the Discriminator evaluates the authenticity of the generated data and whether it meets the conditional constraints. By incorporating this process of conditional dimensionality reduction and restoration, the model effectively preserves key data features and reduces the impact of data imbalance on model training. After receiving the low-dimensional features processed by the Encoder along with the conditional information, the Generator produces new data samples that meet the given conditions. To ensure the diversity and authenticity of the generated samples, the Generator employs adversarial training to continuously optimize its generation capability. The Discriminator is used to distinguish between real and fake input samples while also determining whether the samples meet the given conditions. In this way, the Discriminator not only improves its ability to identify generated samples but also ensures that the generated samples maintain consistency with the feature distribution of the real data.

CE-GAN consists of four key components: an encoder, decoder, generator, and discriminator. While the encoder-decoder pair handles dimensional transformation, the generator creates samples based on low-dimensional features, and the discriminator evaluates both sample authenticity and conditional constraints. The system is trained through multiple loss functions and incorporates modules such as normalization and classifier evaluation to achieve conditional generation.

In data augmentation tasks, enhancing the diversity of the augmented data should be the primary goal. Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis between the improvement in classification performance and the similarity between the generated and original samples. The pseudocode of the CE-GAN model is shown in Table 5, and the improvement in classification model metrics serves as evidence of the effectiveness of the data augmentation algorithm. Additionally, we employed three evaluation metrics for data augmentation: Precision-Recall Distance (PRD), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to validate and quantify the data augmentation effect of CE-GAN. These generation metrics must remain within a reasonable range-neither too high, which would compromise authenticity, nor too low, which would sacrifice diversity. This ensures that the generated samples strike the optimal balance between diversity and authenticity.

During model training, we introduced multiple loss functions to constrain the training outcomes, including adversarial loss, reconstruction loss, diversity loss, and temporal loss. Each loss function plays a crucial role in different parts of the model, contributing to the overall effectiveness of the training process.

Adversarial loss is the core of the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Through the game between the Generator and the Discriminator, the Generator continuously improves the authenticity of the generated samples, while the Discriminator enhances its ability to distinguish between real and fake samples and ensure condition matching. Specifically, the conditional adversarial loss can be described as shown in Eq. (6):

Here, x represents the real data, z represents the random noise vector, c represents the conditional information,G represents the Generator, and D represents the Discriminator.

Reconstruction loss ensures effective data dimensionality reduction and restoration between the Encoder and Decoder. By combining data with conditional information, it enlarges the distribution gap between normal and anomalous samples during the dimensionality reduction process. The reconstruction loss is described in Eq. (7):

Diversity loss is used to ensure the diversity of the generated samples, preventing overfitting and thus maintaining the significance of the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). It also helps to make the generated samples as realistic as possible. The form of the diversity loss is described in Eq. (8):

Here, \(\sqrt{\sum _{k=1}^{d} \left( X_{i,k} - X_{j,k} \right) ^2}\) represents the Euclidean distance between samples \(X_i\)and \(X_j\) , represents the minimum distance between each sample \(X_i\) and other samples \(X_j\) , \(\mathcal {L}_{\text {cst}}\) represented in the form of a small negative mean in the overall training process, Thus, it prevents the generated samples from losing authenticity in the pursuit of model diversity.

Temporal loss is used to ensure that the generated samples in the low-dimensional space are overall similar to the original data, enhancing the reliability of the generated data. The form of this loss is described in Eq. (9):

By combining the four loss functions, the model’s training process is constrained from multiple aspects, accelerating the convergence speed and ensuring both the authenticity and diversity of the generated samples. This balance between authenticity and diversity enhances the quality of the samples generated by the CE-GAN.

As shown in Fig. 6, we have outlined the model architectures used by each network in CE-GAN. Given the high complexity and diversity inherent in network attacks, the multi-head attention mechanism of the Transformer allows for flexible extraction of rich feature representations from the input data. To ensure that both the Generator and Discriminator in the CE-GAN model have equal capabilities, we utilized the Transformer architecture for both, enabling them to handle complex data with consistent feature extraction and representation abilities. Through the multi-head attention mechanism, the model can focus on different parts of the data simultaneously, identifying hidden attack features within a broader feature space. This capability is crucial for recognizing complex network attack behaviors.

Results and analysis

To evaluate the quality of the samples generated by CE-GAN, we selected three commonly used metrics in the field of data augmentation: Precision-Recall Distance (PRD), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). These metrics can quantify the results of CE-GAN using formulas, indirectly reflecting the authenticity and diversity of the generated samples. PRD is used to measure the similarity between the feature distribution of the generated samples and the real samples. By calculating the percentage root mean square difference between the generated and real samples, it assesses whether the generated samples maintain both authenticity and diversity. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. (10).

Here, \(h_i\) represents the real samples,\(s_i\) represents the generated samples, n is the number of samples. PRD is sensitive to the deviation in the overall distribution of the generated samples, reflecting the accuracy of their overall distribution. A smaller PRD value indicates a higher degree of authenticity, but at the same time, a lower level of diversity. RMSE represents the numerical difference between the generated samples and the real samples. It reflects how closely the generated samples match the real samples in terms of value. The calculation formula is shown in Eq. (11).

MAE typically represents the absolute error between the generated samples and the real samples, providing a straightforward reflection of the quality of the generated samples. The formula is shown in Eq. (12).

The smaller the MAE value, the higher the quality of the generated samples, but similarly, the lower the diversity. MAE is equally sensitive to all error values, making it a relatively stable and straightforward measure of error.

K-fold validation

In this section, we first validate the effectiveness of the model through K-fold cross-validation experiments. Using PRD, RMSE, and MAE as the three evaluation metrics, the experiments focus on augmenting rare attack samples in individual classes. As shown in Table 6, we combined buffer_overflow and normal samples to create new datasets. These datasets were divided into K parts, with \(K-1\) parts used as the training set and 1 part as the test set, thereby cross-validating the model’s effectiveness and generalization. According to the metrics, the CE-GAN model generated network attack samples with an average PRD of 64.3868, an average RMSE of 0.1964, and an average MAE of 0.1264, demonstrating good overall performance. These generation metrics confirm the effectiveness of the CE-GAN model.

Multi-loss value experiment

As shown in Fig. 7, we plotted the loss curves for both the Generator’s various loss values and the Discriminator’s loss values. The adversarial loss of the Generator rises rapidly at the beginning of training, while the Discriminator’s loss decreases quickly. Around 400 iterations, the two losses reach a state of balance. The Moment loss and Contrastive loss exhibit a weak adversarial trend throughout the process-one enhancing data diversity and the other enhancing data authenticity. When the two curves reach a balanced and stable state, the model maintains diversity while being grounded in realistic data generation. At this point, the Generator is able to produce diverse samples that meet authenticity standards, effectively augmenting the dataset.

In the experiment, we conducted multiple tests on the composition of the Generator’s loss values. The Generator’s loss function is formulated as shown in Eq. (13), where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are used to control the loss coefficients,typically set to \(\alpha =0.1,\beta =0.01\) , At this value, the balance between the two components remains stable and does not significantly impact the overall training process, However, when \(\beta\) is set to a higher value, the model’s stability decreases, leading to frequent mode collapse issues. Therefore, the degree of diversity should be controlled within a smaller range to minimize its impact on the training process, while still enhancing diversity.

Conditional encode experiment

In current data augmentation research, mainstream approaches predominantly rely on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), typically either inputting the raw dataset directly into the model or applying conditional constraints to the GAN. However, these models commonly face a significant issue: the imbalance in the input data directly affects the learning process of the GAN, leading to the generated distribution being similarly affected by the imbalance problem.

Therefore, this paper aims to improve this issue by addressing it from the model input stage, enhancing the learning distribution of the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). By applying conditional encoding to the input data, the boundaries between different categories can be distinguished after dimensionality reduction, preventing them from being mixed together during the encoding process. As an example, the five main attack categories and their five subcategories in the NSL-KDD dataset are used to verify the changes in data distribution before and after applying conditional encoding.

As shown in Fig. 8, we randomly selected 5,000 samples from the NSL-KDD dataset and visualized the changes in sample distribution using T-SNE dimensionality reduction. From the figure, it is clear that in the original dataset, the data distribution of different categories is mixed, with unclear boundaries between categories. This distribution pattern may lead the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to learn a similarly imbalanced distribution. However, after applying conditional encoding, the data distribution becomes more distinct, and the boundaries between categories are much clearer. This demonstrates that conditional encoding effectively mitigates the impact of data imbalance while performing dimensionality reduction.

When performing augmentation training on network attack data, relying solely on conditional encoding may still result in an overwhelming influence of dominant categories due to the disproportionate quantities of different data types. To further alleviate this issue, during data augmentation, we conducted separate augmentation experiments for each type of network attack, using an equal number of normal network attack types to minimize the impact of imbalance on the data distribution. We selected five attack categories from the NSL-KDD dataset that had fewer samples: buffer_overflow, guess_passwd, land, pod, and warezmaster. These categories effectively demonstrate the boundary distinctions brought by conditional encoding while avoiding the difficulty in visualization due to overly small sample sizes. The effectiveness of conditional encoding was verified for each category. As shown in Fig. 9 conditional encoding, while performing dimensionality reduction, makes the distribution boundaries between different categories clearer, effectively mitigating the impact of data imbalance on model performance.

Single-class data enhancement experiment

When performing augmentation training on network attack data, relying solely on conditional encoding may still result in an overwhelming influence of dominant categories due to the disproportionate quantities of different data types. To further alleviate this issue, during data augmentation, we conducted separate augmentation experiments for each type of network attack, using an equal number of normal network attack types to minimize the impact of imbalance on the data distribution. We selected five attack categories from the NSL-KDD dataset that had fewer samples: buffer_overflow, guess_passwd, land, pod, and warezmaster. These categories effectively demonstrate the boundary distinctions brought by conditional encoding while avoiding the difficulty in visualization due to overly small sample sizes. The effectiveness of conditional encoding was verified for each category. As shown in Table 7, conditional encoding, while performing dimensionality reduction, makes the distribution boundaries between different categories clearer, effectively mitigating the impact of data imbalance on model performance.

Similarly, we performed single-class data augmentation on the UNSW-NB15 dataset using the same approach. We selected six types of rare attack categories from the dataset: Worms, Shellcode, Backdoor, Analysis, Reconnaissance, and Dos. The results are shown in Table 8. For categories like Worms, the phenomenon observed is similar to that in the NSL-KDD dataset, where the augmentation ratio reflects the degree of data scarcity.

After completing the augmentation of the two datasets, we summarized the distributions of the augmented datasets in Table 9. The NSL-KDD augmented dataset showed significant changes in sample data, with categories such as Spy expanding from single digits in the original dataset to hundreds. This increase in recorded data was achieved without overshadowing other categories, and the overall proportion of anomalies in the dataset remained around 50%. Similarly, the UNSW-NB15 dataset saw a notable increase in sample data, effectively addressing the classification model’s performance issues.

Additionally, we redrew the class proportions for both datasets, as shown in Fig. 10. It is visually apparent that the minority samples in the NSL-KDD dataset were effectively augmented through data enhancement. This ensured that while the rare samples were significantly expanded, the overall structure of the dataset remained unchanged. We also increased the proportions of the five major categories-Normal, Dos, Probe, U2r, and R2l. Even U2r, the smallest category by proportion, now contains 3,643 samples, including four subcategories of rare samples, each with around 900 examples. This provides sufficient samples for each class in the dataset, allowing classification models to learn effectively. The UNSW-NB15 dataset’s proportions are similarly shown in Fig. 11.

As shown in Fig. 11, the UNSW-NB15 dataset’s various subcategories were effectively augmented. Even the smallest category, Worms, now contains 20,174 samples. The CE-GAN augmentation not only significantly increased the rare sample categories but also maintained the original structure of the dataset, ensuring that the dataset’s integrity and distribution were preserved. As we can see in Fig. 12, the processed NSL-KDD dataset becomes more robust after augmentation.

Expanded results for multi-category comparison experiment

To further validate the effectiveness of CE-GAN’s dataset augmentation, we input the augmented NSL-KDD dataset into the previously proposed ensemble learning classification algorithm. If the classification metrics improve compared to the original dataset, it would confirm the effectiveness of the CE-GAN data augmentation algorithm, while also indirectly validating the proposed classification strategy. As shown in Table 10 , we conducted comprehensive multi-class experiments on the CE-GAN-augmented NSL-KDD dataset. The results indicate that, after augmentation, CE-GAN showed better performance in Precision, Recall, and F1-score for most attack types. The visualization in Fig. 13 clearly demonstrates the performance enhancement across different metrics before and after applying CE-GAN. Categories like ftpwrite, multihop, and warezmaster saw significant improvements in these metrics, demonstrating CE-GAN’s advantage in handling small or imbalanced sample classification tasks. While some metrics, such as Precision for Normal and Warezclient categories, showed a slight decrease, this reduction is acceptable compared to pre-augmentation results, where categories like loadmodule were entirely unrecognizable. The overall comparative analysis reveals substantial improvements in classification performance, particularly for minority classes. The significant improvements in classification metrics for small sample classes and the enhanced accuracy of the balanced dataset after CE-GAN augmentation demonstrate superior performance, further validating the effectiveness of the CE-GAN model.

CE-GAN model ablation analysis

In CE-GAN, Transformer is used as the primary component in all four parts: Encoder, Decoder, Generator, and Discriminator. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed network architecture, we used the NSL-KDD dataset as an example and replaced the Transformer with more commonly used modules such as GRU, LSTM, MLP, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). Additionally, we tested the removal of the Encoder and Decoder. By comparing the PRD, RMSE, and MAE metrics, we verified the effectiveness of CE-GAN while demonstrating the advantage of using Transformer in all four components of the model.

In CE-GAN, Transformer is used as the primary component in all four parts: Encoder, Decoder, Generator, and Discriminator. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed network architecture, we used the NSL-KDD dataset as an example and replaced the Transformer with more commonly used modules such as GRU, LSTM, MLP, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). Additionally, we tested the removal of the Encoder and Decoder.The comparisons of PRD, RMSE, and MAE metrics across different configurations are presented in Table 11, we verified the effectiveness of CE-GAN while demonstrating the advantage of using Transformer in all four components of the model.

Comparative analysis with classical GAN variants

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of CE-GAN, we conducted systematic comparisons with representative variants from the GAN family. The selected benchmark models include DCGAN, WGAN, CGAN, and InfoGAN. We employed three key metrics - PRD, RMSE, and MAE - for evaluation. As shown in Table 12, the experimental results demonstrate that CE-GAN achieves optimal performance with PRD and MAE values of 64.3868 and 0.1264, respectively. Although WGAN shows a slight advantage in RMSE (0.1932), CE-GAN exhibits more balanced overall performance. These results validate the effectiveness of our conditional encoding and composite loss function while highlighting CE-GAN’s unique advantages in addressing data imbalance issues in network intrusion detection.

Conclusion

In the past decade, artificial intelligence has made significant strides in the field of network attacks, with machine learning algorithms achieving effective results in tasks such as detecting and classifying network attacks. This progress largely depends on the quality of network attack datasets. In this study, we first analyzed the imbalance in the distributions of the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets and proposed a game theory-based classification algorithm to address the imbalance, improving classification performance to some extent. However, when applied to multi-class tasks, the model struggled to recognize rare samples. To address this, we introduced a Conditional Encoding-based Generative Adversarial Network (CE-GAN), which combines an encoder-decoder structure with conditional GAN. Unlike traditional encoder-decoder structures, we incorporated a conditional aggregation method to prioritize the separation of different categories during the learning process, effectively addressing the imbalance issue. The model was trained using a composite loss function to ensure both the authenticity and diversity of the generated samples, while Transformer architecture was used in all components to enhance feature extraction. In experiments, we evaluated CE-GAN using PRD, RMSE, and MAE metrics and compared classification results before and after data augmentation. The results demonstrated the effectiveness of CE-GAN. Additionally, ablation experiments further confirmed the value of the conditional aggregation encoder-decoder method, providing an effective approach for improving network attack datasets.In future work, we plan to evaluate the performance of the CE-GAN model on more representative network attack datasets, such as CICIDS2017, CICIDS2018, and IoT-23, to further validate its generalization capabilities. These datasets encompass diverse attack characteristics across various network environments, which will help comprehensively assess the model’s adaptability and effectiveness in different network attack scenarios. Additionally, we aim to explore the potential application of the model in real-time network traffic analysis, providing more reliable technical support for cybersecurity defense.

Limitations of the study

The limitations of this study are primarily reflected in the following aspects. First, although the CE-GAN model effectively addresses the issue of data imbalance, the diversity and authenticity of the generated samples remain somewhat constrained, particularly when dealing with extremely rare samples, where the model’s performance may not be ideal. Second, The experiments were conducted only on the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets. These datasets may not fully represent attack characteristics in other complex network environments, thus limiting the model’s generalizability. Finally, the complexity of the model is relatively high, especially in practical applications where computational resources and training time could pose challenges. Therefore, its effectiveness in resource-constrained environments may be limited.

Data availability

This study utilizes two publicly available datasets: NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15. The NSL-KDD dataset is provided by the NSL-KDD project and can be accessed via the following link: NSL-KDD. The UNSW-NB15 dataset is provided by the University of New South Wales’ Cybersecurity Research Center, with detailed information and download options available at: UNSW-NB15.

References

He, K., Kim, D. D. & Asghar, M. R. Adversarial machine learning for network intrusion detection systems: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 25, 538–566 (2023).

Alhajjar, E., Maxwell, P. & Bastian, N. Adversarial machine learning in network intrusion detection systems. Expert Syst. Appl. 186, 115782 (2021).

Magán-Carrión, R., Urda, D., Diaz-Cano, I. & Dorronsoro, B. Improving the reliability of network intrusion detection systems through dataset integration. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 10, 1717–1732 (2022).

Dunmore, A., Jang-Jaccard, J., Sabrina, F., Kwak, J. A comprehensive survey of generative adversarial networks (gans) in cybersecurity intrusion detection. IEEE Access (2023).

Yinka-Banjo, C. & Ugot, O.-A. A review of generative adversarial networks and its application in cybersecurity. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 1721–1736 (2020).

Lee, G.-C., Li, J.-H. & Li, Z.-Y. A wasserstein generative adversarial network-gradient penalty-based model with imbalanced data enhancement for network intrusion detection. Appl. Sci. 13, 8132 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Abnormal traffic detection: Traffic feature extraction and dae-gan with efficient data augmentation. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 72, 498–510 (2022).

Babu, K. S. & Rao, Y. N. Mcgan: modified conditional generative adversarial network (mcgan) for class imbalance problems in network intrusion detection system. Appl. Sci. 13, 2576 (2023).

Zhu, N., Zhao, G., Yang, Y., Yang, H. & Liu, Z. Aec_gan: unbalanced data processing decision-making in network attacks based on acgan and machine learning. IEEE Access 11, 52452–52465 (2023).

Sarıkaya, A., Günel Kılıç, B. & Demirci, M. Gru-gbm: A combined intrusion detection model using lightgbm and gated recurrent unit. Expert. Syst. 39, e13067 (2022).

Vo, H. V., Du, H. P. & Nguyen, H. N. Apelid: Enhancing real-time intrusion detection with augmented wgan and parallel ensemble learning. Comput. Secur. 136, 103567 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Nads-ra: network anomaly detection scheme based on feature representation and data augmentation. IEEE Access 8, 214781–214800 (2020).

Park, C. et al. An enhanced ai-based network intrusion detection system using generative adversarial networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 10, 2330–2345 (2022).

Tanha, J., Abdi, Y., Samadi, N., Razzaghi, N. & Asadpour, M. Boosting methods for multi-class imbalanced data classification: an experimental review. J. Big data 7, 1–47 (2020).

Bichler, M., Fichtl, M., Heidekrüger, S., Kohring, N. & Sutterer, P. Learning equilibria in symmetric auction games using artificial neural networks. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 687–695 (2021).

Su, T., Sun, H., Zhu, J., Wang, S. & Li, Y. Bat: Deep learning methods on network intrusion detection using nsl-kdd dataset. IEEE Access 8, 29575–29585 (2020).

Mohammed, B. & Gbashi, E. K. Intrusion detection system for nsl-kdd dataset based on deep learning and recursive feature elimination. Eng. Technol. J. 39, 1069–1079 (2021).

Kasongo, S. M. & Sun, Y. Performance analysis of intrusion detection systems using a feature selection method on the unsw-nb15 dataset. J. Big Data 7, 105 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Research Projects of the Jilin Provincial Department of Education under Grant Numbers JJKH20241705KJ and JJKH20241706KJ. We sincerely thank the Jilin Provincial Department of Education for their generous support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yang Yang led the overall research project, contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, and supervised the entire process, including data analysis and model development. Xiaoyan Liu played a key role in the theoretical framework and methodology, providing significant input in the model construction and optimization process. Dianli Wang was responsible for performing the experiments, conducting data augmentation, and evaluating the model’s performance on various datasets. Qingru Sui contributed to the literature review and provided crucial insights into the application of game theory and Nash equilibrium in classification algorithms. Chao Yang was involved in data preprocessing and preparing the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets for experimentation. Hengxu Li assisted in the implementation of the CE-GAN model and supported the coding and debugging phases. Yifeng Li contributed to the statistical analysis and provided technical support for the experiment setup. Tianyun Luan helped with manuscript editing and formatting, ensuring the overall coherence and quality of the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Liu, X., Wang, D. et al. A CE-GAN based approach to address data imbalance in network intrusion detection systems. Sci Rep 15, 7916 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90815-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90815-5