Abstract

Some studies suggest that behavioral variation among animals destined for reintroduction programs could influence their post-release survival and overall reintroduction success. Therefore, we aimed to test whether individual behavioral differences in white-lipped peccaries (Tayassu pecari - WLPs) influence their exploratory and dispersal behavior after reintroduction. Using a standard ethological approach, we described the behavioral traits of 17 captive WLPs along three dimensions: aggressiveness, exploration, and sociability. Then, using spatial and temporal unpredictability of food supply, we subjected the animals to 90 days of pre-release training. Following this, we moved the WLPs to a pre-release enclosure at the release site in a remnant area of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. In this enclosure, we maintained spatial and temporal unpredictability to provide locally available fruits and roots using the soft release technique. After 32 days, we released the WLPs and tracked their movements for the next 12 months. As expected, WLPs displayed individual behavioral variation across the three dimensions analyzed. While sex and age did not affect their behavioral trait scores, an increase in body weight was associated with heightened aggressiveness. The least sociable WLPs were the first ones to explore and disperse in the release site. Our results showed that the individual behavioral variation indeed influences the exploration and dispersal of reintroduced WLPs. Therefore, to increase the chances of successful reintroduction, it is necessary to develop pre-release training strategies that are tailored to the behavioral traits of the individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among individuals within a population, behavioral differences remain stable over time and across various contexts1,2. In their comprehensive review, MacKay and Haskell3explore the nuances of inter-individual behavioral differences, often termed temperament, personality, or behavioral syndromes. Temperament refers to innate behavioral tendencies, while personality encompasses more complex traits shaped by experience3. Behavioral syndromes involve correlated behaviors across different contexts3. A thorough understanding of these distinctions clarifies how consistent individual behavioral variations manifest and are studied in animals. Building on the framework proposed by Laskowski et al.4, we will refer to these differences as individual behavioral differences. These inter-individual variations can significantly influence how individuals engage with their environment5. For example, individuals exhibiting higher levels of boldness tend to be more proactive6,7,8and, therefore, more inclined to explore new resources compared to their shy counterparts9. Evidence suggests that more exploratory individuals exhibit higher survival rates and travel longer distances post-release, as observed in Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii)10. Such behavioral traits may also influence individuals’ responses to approaching predators, potentially exposing them to unnecessary risks6,7, or impact woody plants due to seed dispersal patterns11,12. Variations and correlations in these behavioral traits impact population estimates, resource selection models, population dynamics, responses to disturbances, and reintroduction success13. For these reasons, some studies suggest that individual behavioral differences in animals destined for reintroduction programs may influence their post-release survival, dispersal and reintroduction success14,15,16. Behavior shaped by captivity can significantly impact survival rates, with bold individuals experiencing higher mortality in the wild, underscoring the necessity for careful selection14,15. Therefore, it is crucial to consider both individual behavioral differences and adaptability for successful reintroduction, as these factors influence the ability to adapt to new environments16,17.

In addition to assessing individual behavioral differences, environmental enrichment (EE) techniques18stand out as a practice for pre-release training of animals. These techniques allow for the recovery of behaviors that may be absent or diminished in animals born and raised in captivity, such as exploratory and defensive behaviors19 that are fundamental to their survival. For example, EE techniques that exploit the spatial and temporal unpredictability of food supply are considered promising for success in reintroduction programs for species such as the white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari)20,21.

The white-lipped peccary (WLP), a neotropical artiodactyl, is classified as vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), primarily due to overhunting, deforestation, and habitat fragmentation22,23,24. In Brazil, the species has experienced a reduction of approximately 60% from its historical range25. Oshima et al.25concluded that of the 40% of Brazil’s territory suitable for WLP, only 12% is under protection. In the Atlantic Forest, merely half of the protected areas serve as suitable habitats for WLPs. Consequently, the extirpation of WLP from the Atlantic Forest has been continuously documented26,27,28. The situation is equally severe in other Brazilian biomes, including the Pantanal, Cerrado, and Caatinga, where only 44%, 14%, and 7%, respectively, of these biomes serve as suitable habitats for WLPs25. Moreover, it has recently been reported that the species is subject to an intrinsic dynamic in which environmental and biological factors regulate its population growth29. Herds of WLPs, which can number hundreds of individuals, continuously travel long distances along trails in search of food30,31. Due to the action of these large numbers of animals in creating and maintaining trails, as well as the large ponds in which they wallow, the species is recognized as an ecosystem engineer22. Furthermore, WLPs play critical roles as both dispersers and predators of seeds and seedlings, interacting with diverse plant species and influencing the phytophysiognomy of their habitat32,33,34,35. They also serve as primary prey for large cats like the jaguar (Panthera onca)36. The absence of WLPs can trigger cascading effects on biodiversity, underscoring their significance in maintaining ecological balance within tropical forests37.

Reintroduction programs have been widely implemented, with varying levels of success38. Release protocols can be categorized as either hard or soft, considering factors such as the choice of release site, the source of animals, and the provision of pre- and post-release support39. Soft releases include post-release support such as food, shelter, and water40. This protocol frequently includes an initial phase of on-site confinement, which allows animals to acclimate to their new environment, thus lowering mortality rates41. However, this method can sometimes result in failures. Moseby et al.38proposed a more effective strategy, which involves categorizing the scenarios in which specific reintroduction protocols are most likely to succeed. In this context, key factors to consider include life history and behavioral traits38.

Efforts have been made to reintroduce the WLP to areas from which it has been extirpated, emphasizing its ecological significance42,43. Figueira et al.42 employed a soft-release protocol to reintroduce WLPs to a tropical savanna region (Cerrado) in Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. However, according to one of the study’s authors, even a year after their release, the animals continued to depend on supplemental food provided by researchers (M. Figueira, personal communication, 2004). In response, Nogueira et al.21conducted a study to assess the efficacy of environmental enrichment programs during pre-release training for WLPs born and reared in captivity. The findings indicated that the introduction of spatially and temporally unpredictable food sources enhanced the exploratory behavior of WLPs, a beneficial outcome for reintroduction programs. Furthermore, the use of a whistle to signal the availability of food led to sustained increases in exploratory behavior, thereby enhancing the prospects for successful reintroduction efforts21. However, to date, this pre-release training technique has not yet been tested on animals that are candidates for release. Therefore, here we applied this technique to assess whether WLPs extend their exploratory behavior after release. Additionally, we aimed to determine whether individual behavioral differences influence exploratory and dispersal behavior in a reintroduction program.

Based on the findings of a previous study, which demonstrated that white-lipped peccaries maintained significant interindividual behavioral variability even after several generations in captivity44, it is reasonable to expect that the peccaries in this study will also exhibit considerable behavioral variability. The impact of intrinsic factors such as sex, age, and body weight on individual behavioral differences remains a complex and uncertain phenomenon across species2. In many species, maturity brings distinct challenges and environmental pressures for males and females, resulting in variations in life-history and behavioral traits. For instance, in horses (Equus ferus caballus), sex significantly influences reactions to fear-inducing stimuli, with mares being generally less reactive than stallions45. Conversely, WLPs show no significant sex-based differences in behavioral traits under challenge tests44. Behavioral changes post-maturation are noted in species like guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus)46 and yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris)47. In contrast, stable behavioral traits from juvenile to adult stages are observed in bighorn ewes (Ovis canadensis)48and Wistar rats49, for example. Additionally, while lighter mice (Mus musculus) exhibit more anxious behavior and spatial learning challenges, such as navigating a maze50no relationship exists between body weight and behavioral differences in bighorn ewes48. While intrinsic factors such as sex, age, and body weight may or may not influence individual behavioral differences in WLPs, certain characteristics of this species, combined with previous study findings, enable the formulation of the following predictions. Given the lack of observed behavioral trait differences between male and female WLPs44, we do not expect correlations between sex and behavioral trait scores. Previous studies have identified exploratory and defensive threat/attack patterns as typical responses of WLPs when encountering novel environments and risk challenges51. Consequently, we expect the most aggressive individuals to be the first to explore the environment during the soft release phase and to disperse following release. Furthermore, considering the established positive correlation between body weight and dominance ranking in WLPs52,53,54,55, we anticipate that heavier and older WLPs will exhibit higher aggressiveness scores. Given that WLPs are known to live in cohesive herds30,31, individuals with high sociability scores are likely to show reduced tendencies to disperse when seeking food resources.

Methods

Animals and study sites

Seventeen adult WLPs were observed, 10 males (mean body weight = 38.0 kg; standard deviation (SD) = 3.6) and seven females (mean body weight = 36.4 kg; SD = 6.9), ranging in age from 4.7 to 11.4 years old (mean age 5 years old; SD = 3.8) (Table 1). The animals under investigation comprised a unique group, having undergone captive breeding and rearing processes for six generations at the Laboratory of Applied Ethology at the State University of Santa Cruz (LABET/UESC). In addition to white-lipped peccaries, LABET also studies and maintains in captivity other Neotropical animals, including collared peccaries (Dicotyles tajacu), paca (Cuniculus paca), and chestnut-bellied seed finches (Sporophila angolensis). Selene Nogueira, the principal investigator of this study, possesses extensive experience in managing white-lipped peccaries in captivity. She has authored numerous publications on the behavior and management of this species.

All individuals were marked with plastic ear tags cut into different shapes to allow identification at a distance. Moreover, all animals received systematic treatment under an anti-parasite protocol and underwent periodic veterinary assessments throughout the study. The study comprised three phases: pre-release training and assessment of individual behavioral differences (PT), soft release (SR), and post-release (PR). These phases are described in detail below. The data collection began in August 2022 (PT) and concluded in March 2024 (SR). The PT phase was conducted at LABET-UESC in Ilhéus, Bahia, Brazil (14°47’39”S; 39°10’27”W). At this laboratory, the WLPs were housed in a 940 m² paddock surrounded by a 1.5 m high chain-link fence. The paddock had a dirt floor and was divided into two sections: the refuge area (564 m2) with dense shrubby vegetation and medium-sized trees; and the feeding area (376 m2), with no shrubby vegetation, which allowed for the observation of individuals in a fully visible manner. In the feeding area, there was a corral-trap (10.0 m long x 3.0 m wide), which was employed for the capture of animals when necessary. This section also included nine challenge-feeders (see details below). Additionally, two drinking water troughs (0.3 m long x 0.3 m wide x 0.2 m high) were present, one in the refuge area and the other in the feeding area (Fig. 1A), with an ad libitum water supply.

(A) Schematic drawing of the experimental paddock for the pre-release training and inter-individual behavioral variation assessment at Laboratory of Applied Ethology (LABET/UESC), modified from Nogueira et al. (2014). (B) Schematic drawing of the pre-release enclosure at the Wild Animals Rehabilitation Center of the Brazilian Environmental Agency (CETAS/IBAMA) in Porto Seguro, Bahia, Brazil. Both enclosures included a corral-trap, marked by a hexagonal symbol, used for animal capture when necessary. The refuge area of the experimental paddock and the vegetated section of the pre-release enclosure were densely filled with shrubs, significantly obstructing animal visibility.

The SR phase took place at the Pau-Brazil Ecological Station near the Wild Animals Rehabilitation Center of the Brazilian Environmental Agency (CETAS/IBAMA) in Porto Seguro, Bahia, Brazil (16°23’1”S; 39°10’28”W). The WLPs were placed in a pre-release enclosure (30.0 m long x 20.0 m wide) constructed within the forest in which they were subsequently released. The relatively modest dimensions of this enclosure (600 m²) can be attributed to the financial and logistical challenges encountered in purchasing and transporting the materials utilized for its construction. In contrast, the previous phase employed a larger paddock (940 m²). Despite the constraints imposed by the enclosure, the structural characteristics permitted the gradual acclimatization of the animals to their release area in accordance with the soft-release technique56. One-half of the pre-release enclosure (30.0 m long x 10.0 m wide) was densely vegetated with shrubs (vegetated section), making it impossible to observe the animals within that area. The remaining half (observation section) had sparse shrub vegetation, enabling an observer to view the animals from a 2.0 m platform constructed above the perimeter fence (Fig. 1B). The observation section contained a corral-trap (5.0 m long x 1.5 m wide), four feeders and two drinking troughs, with an ad libitum water supply.

The Pau-Brazil Ecological Station encompasses 11.6 km2 and is contiguous with the Estação Veracel Private Nature Reserve, totaling 60.7 km2. Together, they form a 72.3 km2 fragment spanning Porto Seguro and Santa Cruz Cabrália in Bahia (Fig. 2). This area represents a significant portion of the Atlantic Forest in southern Bahia. Based on camera trap data and direct and indirect signs of mammalian activity, Magioli et al.57found 31 species of medium and large-sized mammals, with 26 species found in Estação Veracel Private Nature Reserve and 31 in Pau-Brazil Ecological Station. The collared peccary, the other peccary, was recorded only in Pau-Brazil Ecological Station. However, the WLP is extinct in both areas, with no records of the species since 201857. Both LABET/UESC and CETAS/IBAMA are situated in regions characterized by an average annual temperature ranging from 22º to 25ºC, consistent with the humid tropical climate of Brazil’s east coast58.

Imagery provided by Google Earth V 7.3.6.9750 (April 14, 2024). Map of the release area, formed by the union of the Pau-Brazil Ecological Station and the Estação Veracel Private Natural Heritage Reserve (RPPN); the arrow indicates the location of the pre-release enclosure built for the soft release phase. https://www.google.com/earth/.

Throughout all three phases (PT, SR, and PR), the animals were fed a basal diet consisting of a mixture of coarsely ground corn grain and coarsely ground soybean meal, supplemented with vitamins and minerals. This formulation contained 12% crude protein within the dry matter (DM) and 13.8 MJ/kg DM of crude energy, designed to fulfill the nutritional requirements of the species, as determined by Nogueira-Filho et al.59. During the SR phase, the basal diet was enhanced with locally sourced fruits and roots collected from the release area, in accordance with the seasonal availability of these resources. These included native and exotic fruits, which are part of the natural diet of WLPs, such as mango (Mangifera indica), jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), guava (Psidium guajava), cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum), and cassava (Manihot esculenta)34,60,61. Furthermore, other locally available fruits were also provided, including papaya (Carica papaya), oil palm fruits (Elaeis guineensis), and jambo (Eugenia malaccensis).

In this study, two types of feeders were employed: conventional-feeders (SR and PR phases) and challenge-feeders (PT phase). The conventional-feeders were constructed from longitudinally split tires (Supplementary Figure S1a), while the challenge-feeders (Supplementary Figure S1b), were based on the model previously tested with peccary (Dicotyles tajacu)20and WLPs21. The challenge feeders were constructed using 1.0 m-long PVC tubes (150 mm in diameter) and were equipped with a sprung door measuring 0.30 m in height by 0.15 m in breadth20. The design of challenge-feeders is such that the animals must exert effort to access the food, which encourages prolonged periods of exploratory behavior and emulates natural foraging behavior21.

Pre-release training and individual behavioral variation assessment phase (PT)

During the initial phase of the study (PT), WLPs underwent a seven-day habituation period to acclimate to the presence of the observer. We considered this duration sufficient for habituation because, after the fourth day, the animals’ behavior remained consistent regardless of the observer’s presence. Subsequently, training sessions were conducted to familiarize the animals with challenge-feeders (Supplementary Figure S2). Following this, the WLPs were trained to enter the feeding area upon hearing a whistle as described by Nogueira et al.21. Briefly, the caregiver blew a plastic whistle to signal to the animals that food was being offered in the feeding area. Subsequently, the caregiver would open the door, allowing the WLPs access to the feeding area, thereby reinforcing the association between the whistle and the availability of food. Once trained, the caregiver opened the door, granting the WLPs access to the feeding area, and establishing the association between the whistle and the presence of food. During this phase, we provided the basal diet at 3.5% of the animals’ daily body weight on a dry matter basis. To provide spatial unpredictability, food was distributed daily among six randomly selected challenge-feeders out of the nine available ones, fostering a dynamic search for food, as recommended by Nogueira et al.21. Furthermore, temporal unpredictability was introduced by randomly assigning two feeding times between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m.

The third author of this study assessed individual behavioral differences in the WLPs through two daily observation sessions, one in the morning and one in the afternoon, over 12 days. Observations were recorded using a single GoPro camera (GoPro Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) positioned approximately 10 m from the center of the feeding area, providing comprehensive observation of all group members. Throughout this phase, the observer continuously recorded the focal animals’ behavioral data62. During each session, up to 12 individuals were observed individually for 5-minute periods. The focal observation order was randomly selected, ensuring that individuals previously observed in the same session were excluded. This approach resulted in a total of 60 min of observation per individual and 1,020 min (17 h) of behavioral data collection overall. Given that white-lipped peccaries are continuously observed interacting with one another, both agonistically and affiliatively, as well as exploring their environment52,55, this observation period was sufficient to reveal interindividual differences in their behavior (see Results).

Upon completing the observations, a single observer, unaware of the study’s broader objectives, reviewed the recorded footage using BORIS software63. This observer quantified aggressive actions initiated by focal individuals and their time spent in exploratory and affiliative behavior patterns (Table 2). Two independent observers reviewed 5.1 h (30%) of the recorded footage to validate the findings. The Kappa concordance test was applied to assess the reliability of the behavioral pattern classifications, showing substantial agreement among observers (Kappa = 0.98, p < 0.001 for agonistic behaviors; Kappa = 0.96, p = 0.021 for exploratory behaviors; and Kappa = 0.91, p = 0.023 for affiliative behaviors). Subsequently, the data were centralized using z-score transformation [z-score = (original data point - mean) / standard deviation] to establish scores for the three dimensions of individual behavioral variation: aggressiveness, exploration, and sociability, as outlined by Réale et al.2 (Table 2). The z-score transformation standardizes data, facilitating the comparison of different sets on a common scale by eliminating the influence of varying units or magnitudes. The process centers the data around zero by subtracting the mean from each point, which results in mean values that are at or near zero64.

Following Sowls65 and Nogueira-Filho et al.52, we considered aggressive behavioral patterns among WLPs to be the actions involving postural displays of dominance directed towards others, such as threat and pushing, or threats, attacks, or postural displays of dominance directed towards others (Table 2). As per the cited papers, we defined exploratory patterns as actions undertaken by WLPs to investigate and interact with their environment, such as foraging and investigating the ground (Table 2). Finally, also following Sowls65 and Nogueira-Filho et al.52, we categorized affiliative behavioral patterns as those that promote social bonds and cohesion within a group, such as mutual rubbing and social grooming (Table 2).

Soft-release phase (SR)

The WLPs remained in the PT environmental enrichment program (challenge-feeders and both spatial and temporal unpredictability of food) for a period of three months. This period was deemed sufficient as the animals were fully trained to respond to whistle commands and utilize the challenge feeders. Additionally, during this time, we gathered ample information on individual behavioral differences (see Results). After a veterinary check declared them healthy, they were moved to the SR phase (Supplementary Figure S3). They were transported from LABET/UESC to CETAS/IBAMA on December 7th, 2022, covering 275 km in six hours with three stops to cool them down. Upon arrival, they were fed the basal diet in the pre-release enclosure. The SR phase began on December 8th, 2022, and ended on January 19th, 2023, lasting 32 days. Throughout this period, an observer used scan sampling62 to monitor the location of each individual within the enclosure, distinguishing between those in the vegetated section and those in the observation section. This observation was conducted every 15 min for an hour after food was provided. During this phase, food timing remained unpredictable, with two random feeding times assigned between 8 am and 4 pm. Challenge-feeders were not used to avoid excessive human contact. The basal diet, adjusted to 2% of the animals’ daily body weight on a dry matter basis, was supplemented with locally sourced fruits and roots to compensate for deficiencies. The basal diet was evenly distributed among four conventional feeders for two daily meals. To encourage exploration, these feeders were placed five meters apart in the observation section, and fruits and roots were scattered throughout the enclosure. By the sixth day following their introduction to the pre-release enclosure (see results), behavioral assessments indicated increased exploration and regular consumption of local food, indicative of habituation. Consequently, we concluded this phase on day 32 as no further behavioral changes were observed.

Post-release phase (PR)

Following the conclusion of the SR phase, the animals were released by opening the pre-release enclosure doors on January 10th, 2023, thereby initiating the PR phase (Supplementary Figure S4). The doors of the pre-release enclosure were opened by the first author of this study, who immediately positioned himself on the observation platform and recorded the WLPs’ behavior. Over the subsequent 12-month period, the WLPs were monitored as they gradually acclimatized to the release area. During the PR phase, two water troughs and four conventional feeders were relocated approximately 10 m from the pre-release enclosure. For the initial six months, both water and basal diet were offered once daily at random times between 8 am and 4 pm, maintaining temporal unpredictability to encourage exploration. The amount of basal diet gradually decreased every 30 days, from 2 to 0.5% of the animal’s body weight on a dry matter basis. Similarly, the quantity of fruits and roots offered decreased from 1.5 to 0.5% of their body weight on a dry matter basis (Supplementary Table S1). We stopped providing food in the seventh month after release, while water remained available ad libitum during the 12-month monitoring period. Group members were monitored using radio-collaring techniques, camera traps, and tracking observations within the release area.

The first author of this study conducted monthly monitoring of the group members’ movements using radio-collaring techniques within the release area from January 10th, 2023, to May 10th, 2023, covering the initial four months of the PR phase. Following this period, he continued to monitor the group’s movements monthly through trace tracking and camera traps until January 10th, 2024. This monitoring provided data on individual dispersal patterns, dietary intake, notable behaviors like aggression, and occurrences of births and mortality (Supplementary Table S2). Given the social cohesion among WLPs30,31, monitoring through radio collars, image capture, and signal detection allowed for comprehensive tracking of collective group movements. Before implementing radio-signal monitoring, the release area was mapped and divided into grid lines, creating square plots of 0.02 km2 each. These plots were assigned numerical identifiers, serving as spatial reference points for radiolocation-based surveillance. Throughout the 12-month PR phase, residual imprints within the release area were traced weekly. This tracking involved systematic coverage of animal pathways, from the pre-release enclosure to the furthest extent of discernible traces, including indicators like disturbed foliage, footprints, and fecal deposits. Such efforts facilitated the monitoring of animal dispersal trajectories and guided strategic placement of camera traps and radio receivers. Additionally, tracking provided insights into the animals’ use of local food resources and monitored access to natural water sources, such as springs, pools and streams.

Radio collars were fitted onto four males and two females (Table 1) 18 days before their release. The animals were captured and immobilized in a trap pen, then chemically restrained by a veterinarian using a combination of ketamine (4.0 mg/kg of body weight), midazolam (0.5 mg/kg of body weight), and xylazine (0.2 mg/kg of body weight) injected via a syringe attached to an applicator stick. Each radio-collar, weighing 0.14 kg, operated within the ultra-high frequency range (UHF) of 2.4 GHz (Bluetooth technology), with a range of approximately 5.0 m. The signal was monitored with a set of 20 compatible receivers, including smartphones with a Bluetooth signal monitoring app, each equipped with an additional battery accessory. The radio collars were equipped with a self-release mechanism that employed a biodegradable clasp constructed from suture and latex rubber hose.

Monitoring using radio collars was limited to the first four months of the PR phase, aligning with the battery life of the transmitters and the decomposition of the biodegradable clasps, leading to collar release. The receivers were relocated monthly in woodland plots surrounding the enclosure, selected based on previous animal trace monitoring. The data from each receiving station were plotted on a map monthly to generate graphs illustrating the individual movements of the animals during the radio monitoring period. The radio receivers were also used to record the sequence order in which the WLPs approached the receivers as they gradually moved away from the pre-release enclosure in the forest. Typically, animals that reach the new receivers’ location first are the most daring explorers. Concurrently, continuous camera trapping was conducted throughout the PR phase, using 10 trap cameras (model 801 A, HC, China).

Due to the intensity and time-consuming nature of the activities conducted during both the SR and PR phases, the CETAS/IBAMA personnel available for animal monitoring were fully occupied. Consequently, no other mammal species were released in the study area throughout the entire release period.

Data analysis and statistics

We confirmed the normal distribution of scores for the three dimensions of individual behavioral variation—aggressiveness, exploration, and sociability—using Shapiro-Wilk tests. To assess the variability of the scores for these behavioral trait dimensions, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV%) for each dimension. The coefficient of variation is obtained by dividing the standard deviation by the mean and multiplying by 100, providing a measure of relative variability. A lower CV% indicates low variability, while a higher CV% indicates high variability66. However, as previously mentioned, the z-score transformation results in mean values that are at or near zero64. Because calculating the coefficient of variation (CV%) for a data set with a mean of zero results in a division by zero, which is mathematically undefined, we calculated the CV% for the original behavioral data of each dimension before applying the z-score transformation. Following this, we used Student’s t-tests to assess sex differences in individual behavioral trait scores across the three evaluated dimensions. Spearman’s rank correlation tests were employed to examine the associations between the individual behavioral trait scores, body weight, and age. We also used Spearman’s rank tests to assess the associations between individual behavioral trait scores, body weight, and age, with the latency in days they took to be observed in the observation section during the SR phase.

During the PR phase, extensive data were collected on mating, births, deaths, food consumption (both supplied and from natural resources), and the dispersal of group members. Using the monthly recorded data of each radio-collared individual (N = 6), we calculated the mean sequence order in which individuals approached the radio receivers as they gradually moved away from the pre-release enclosure in the forest (Supplementary Table S3). Subsequently, we employed Spearman’s rank correlation tests to investigate the relationship between the mean sequence order of approach and the individual behavioral trait scores, body weight, and age of the six WLPs fitted with radio transmitters. Statistical analyses were conducted using Minitab v. 21.4.3, with a significance level set at α ≤ 0.05.

Results

Individual behavioral trait scores

The individual behavioral trait scores for the aggressiveness dimension ranged from − 0.64 for the least aggressive individual (Preta) to 1.68 for the most aggressive individual (Peixe) (Table 1). For the exploration dimension, scores ranged from − 0.30 for the least exploratory individual (Topete) to 0.26 for the most exploratory individual (Branca) (Table 1). In the sociability dimension, scores ranged from − 1.00 for the least sociable individual (Losango) to 1.24 for the most sociable individual (Preta) (Table 1). The original data, including aggressive actions initiated by focal individuals and their time spent in exploratory and affiliative behavior patterns, showed high variability across the three behavioral trait dimensions (aggressiveness: CV = 56.9%; sociability: CV = 73.8%; exploration: CV = 195.1%). No significant differences were found between males and females regarding age (males: mean = 8.1 years, SD = 1.9, females: mean = 8.3 years, SD = 2.1, t-Student = 0.18, p = 0.86), body weight (males: mean = 38.0 kg, SD = 3.6, females: mean = 36.4 kg, SD = 6.9, t-Student = -0.55, p = 0.60), or individual behavioral trait scores across the three evaluated dimensions (aggressiveness – males: mean = 0.14, SD = 0.60, females: mean = −0.21, SD = 0.49, t-Student = -1.55, p = 0.15; sociability – males: mean = −0.21, SD = 0.65, females: mean = 0.31, SD = 0.80, t-Student = 1.44, p = 0.10; exploration – males: mean = 0.00, SD = 0.19, females: mean = 0.00, SD = 0.22, t-Student = −0.02, p = 0.98). Additionally, no correlation was detected among the individual behavioral trait scores of the three dimensions (Table 3). Nevertheless, a positive correlation was observed between the aggressiveness scores and the body weight of WLPs (Table 3). Thus, as body weight increases, the aggressiveness of WLPs also increases (Fig. 3). Moreover, there was a positive correlation between the body weight of WLPs and their age (Table 3).

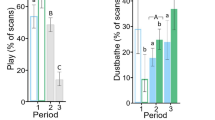

Relationship between individual behavioral trait scores, body weight and age and the exploration behavior of white-lipped peccaries during the SR phase

Following their introduction to the pre-release enclosure utilized in the SR phase, all WLPs remained within the vegetated section of the enclosure for the first two days (Fig. 4). On the third day, two individuals (Losango and Peixe) were observed exploring the observation section of the enclosure. On the fifth day, three other individuals (Branca, Baleia and Árvore) were also seen in the observation section (Fig. 4). From the sixth day, all WLPs were observed exploring the observation section (Fig. 4).

There was no correlation between individuals’ behavioral trait scores in the three dimensions analyzed (aggressiveness, exploration and sociability) and the latency they took to be spotted exploring the observation section of the pre-release enclosure (Table 4). However, negative correlations were observed between the age and body weight of the individuals and the latency in days they took to be seen in the observation section of the enclosure used in the SR phase (Table 4). Consequently, the younger and lighter animals required a shorter period to explore the observation section of the pre-release enclosure.

Relationship between individual behavioral trait scores, body weight and age and the dispersion of WLPs during the PR phase

All WLPs spontaneously left the pre-release enclosure 25 min after the doors were opened. The first individual to leave was the female Seta, the third most exploratory individual in the group (Table 1), followed by the other animals who left the pre-release enclosure almost at the same time.

Although no mating behavior had been observed during the PT and SR phases, on March 14th, 2023, the presence of a juvenile was documented in the center of the group through camera trap images. A copulation was recorded by the camera traps on the fifth day of the PR, on January 15th, 2023, in the vicinity of one of the conventional feeders in the release area. On September 3rd, 2023, a second juvenile was observed in the middle of the group. On September 25th, 2023, 260 days after the WLPs were released, the male Naruto was observed with the group, showing signs of injury and limping. This observation was made by one of the field assistants while following the tracks left in the release area. The animal was attracted by the offer of food inside the pre-release enclosure, along with the use of the whistle used during training at PT. It was subsequently recaptured. A veterinarian conducted an examination that revealed deep bite marks inconsistent with those of WLPs. Despite treatment, the wounds caused sepsis and the animal died three days after capture.

We identified different feeding sites in the release area by following the tracks left by the animals. These tracks were identified by the presence of overturned soil, traces of fruit, and root consumption. The first natural food resource available in the release area and consumed by the WLPs was the fruit of the sapucainha (Carpotroche brasiliensis) (Supplementary Table S4). Tracking also revealed that although the animals gradually moved away from the release area, they consistently returned to the pre-release enclosure to consume the food (basal diet) placed in the conventional feeders. No leftover food was observed during the entire seven-month period that food was provided.

Analysis of the footprints of the animals showed that the water in the water troughs was consumed at a minimal rate from the ninth month after the animals were released. This was indicated by the small change in water level observed from one day to the next. In contrast, the use of various natural water sources in the release area was evidenced by WLPs’ tracks leading to springs, ponds, and streams (Supplementary Table S4). Additionally, footprints belonging to other species, including the puma (Puma concolor), the tapir (Tapirus terrestris), and the collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu), were observed along the trails left by the animals. Furthermore, the presence of a feral dog (Canis lupus familiaris) was recorded in camera trap images 25 days after the animals were released, indicating that the dog was roaming the area during the PR phase.

Radio-collared monitoring conducted during the first four months after release indicated that individuals were present at locations that were progressively further away from the pre-release enclosure. Linking the coordinates of each of these fixed stations (Fig. 5A) resulted in polygons whose areas gradually increased from 0.02 to 0.53 km² (Table 5). The sequence order in which individuals approached the radio receivers was negatively correlated with their sociability scores (Table 6). Consequently, the least sociable individuals were the first to approach the receivers as they moved away from the pre-release enclosure (Fig. 6).

Imagery provided by Google Earth V 7.3.6.9750 (April 14, 2024). (A) Polygons formed by linking the coordinates of the monitoring stations that recorded the animals’ radio signal during the first four months of radio monitoring. (B) Polygon formed on Jan 10th 2024 by linking the coordinates of the trace tracking and camera trapping after the end of the monitoring period (polygon # 5 in light green); in the center of the image is the area occupied by the white-lipped peccaries at the end of the radio monitoring on May 10th 2023 (polygon # 4, in purple), as well as the location of the pre-release enclosure. https://www.google.com/earth/.

Radio monitoring was discontinued after the fourth monthly measurement in May 2023, when the transmitter batteries ran out. The biodegradable clasps on the collars gradually opened after the fifth month of the PR phase, when two collars were found on one of the trails opened by the animals. Although no other collars were found, the animals were not wearing collars from the sixth month of PR. From the fifth measurement, in June 2023, no signs of the animals were captured at the reading stations. Tracking and camera trap monitoring continued throughout the PR, providing dispersal data after the radio-collar period ended. As a result, it was possible to verify that the animals used an area of 244.72 ha (2.45 km²) around the pre-release enclosure at the end of the study in January 2024. This area, identified by polygon # 5 (Fig. 5B), is bounded to the north and east by a tributary of the Camuruji stream, to the south by cupuaçu (Theobroma grandiflorum) plantations at the Pau-Brazil Ecological Station, and to the west by the access road to the RPPN Veracel Station.

The ear tags used to identify WLPs at a distance during the PT and SR phases were lost during the PR due to friction with native vegetation, preventing individualization of the animals using the camera traps. Monitoring of the group for this study ended on January 10, 2024, one year after their release. At that time, the group contained 18 animals, 16 of which were from the original reintroduction group and two young born after the reintroduction. Even after the end of the data collection phase of this study, the first author continued to monitor the animals monthly and recorded the birth of two more young on March 1st, 2024.

Discussion

As expected, WLPs exhibited individual behavioral variation across the three dimensions analyzed. The absence of a deliberate selection process44likely contributed to the maintenance of this diversity, as such processes can reduce behavioral variation and negatively impact reintroduction success67. Factors inherent to captive breeding that typically led to a loss of diversity were not present in this population. Normally, captive breeding favors individuals that are more adaptable to the captive environment, inadvertently selecting traits advantageous in captivity, thereby reducing wild fitness68,69. Additionally, predictable and controlled environments typically lead to habituation and reduced diversity67. However, in this laboratory setting, WLPs were raised in a semi-captive environment and exposed to a wide range of stimuli, such as foraging for fruits in the refuge area, which provided environmental enrichment and allowed for the expression of a broader range of natural behaviors, thus maintaining higher behavioral diversity.

Additionally, our findings revealed no differences between females and males in the scores for aggressiveness, sociability, and exploration, confirming the prediction that sex does not affect these dimensions of individual behavioral variation in WLPs. This outcome aligns with previous studies that have shown no behavioral trait differences between male and female WLPs when subjected to challenge tests44. Furthermore, male and female WLPs exhibit no apparent sexual dimorphism65. Both sexes compete equally for resources, with sex playing no role in determining hierarchy or behaviors such as exploration and affiliative interactions52,54,55. Our results also indicated that heavier individuals exhibited higher aggressiveness scores, consistent with previous studies that have verified a positive correlation between body weight and rank in WLPs, with the most dominant individuals asserting their dominance through aggression52,53,54,55.

Our results empirically support the hypothesis that individual behavioral variation influences the exploration and dispersal of WLPs. Specifically, during the post-release phase (PR), initial exploration and dispersal were primarily driven by individuals exhibiting lower levels of sociability. These individuals demonstrate higher levels of boldness and curiosity compared to those arriving later. We predicted this result due to the high cohesiveness observed in WLP herds, as noted by Fragoso30,31. Consequently, it is reasonable to infer that highly sociable individuals are more inclined to remain with the group rather than wander off on their own to find food. The relationship between sociability and dispersal is important for the comprehension of animal resource utilization and spatiotemporal movement patterns70,71. Therefore, the behavioral traits of the species may provide an explanation for the death of the male Naruto, which occurred 261 days after its release. It should be noted that this animal was the youngest male in the group, as well as one of the least sociable and one of the individuals who led the dispersal of the group. It is reasonable to assume that it remained isolated from the group, thereby becoming more vulnerable to predator attacks. Individuals in a group of WLPs collectively defend themselves against predation by large felids such as the jaguar65, which may explain the proverb that states: “a white-lipped peccary out of the pack is jaguar food”.

The species that caused the animal’s injuries could not be confirmed with certainty. The possibility that this animal was attacked by other individuals in the group does not seem likely, as the wounds are inconsistent with WLP bites. Therefore, it is possible that the bites found on this animal were the result of a predatory attack when it was isolated from its group. A photograph of a feral dog was captured by a camera trap during the PR. Although the occurrence of feral dogs in the area is relatively infrequent, they do occur, and this raises the possibility of an aggressive encounter. However, given the documented behavior of WLPs in confronting and even killing dogs72, it seems unlikely that a feral dog would have attacked the animal in question. An alternative hypothesis suggests that the bite wounds on Naruto’s body may have been inflicted by a puma (Puma concolor), supported by the presence of footprints found at the release site. Despite the absence of anti-predation training in our protocol, Naruto’s death occurred more than six months after its release, indicating some success in evading predators. This suggests that the reintroduction of WLPs has restored natural prey-predator interactions at the site, as occurred alongside the reintroduction of wolves (Canis lupus) into parts of Yellowstone National Park73.

However, contrary to expectations, there was no correlation between the individual exploration scores and the latency it took the most exploratory individuals to explore the observation section of the pre-release enclosure in the soft-release phase (SR) or to disperse in the post-release phase (PR). The answer may lie in the fact that the exploration dimension is not necessarily linked to ‘risk-prone’, and it needs to be assessed by a different approach, considering biological and ecological circumstances46. An alternative hypothesis suggests that the more exploratory individuals may have ventured into the observation section beyond our scan sampling, making it impossible to watch them. Conversely, although no correlation was observed between age and individual exploration scores, we identified a negative correlation between individuals’ age and the latency in days before they were observed in the pre-release enclosure. The findings suggest that younger individuals exhibit shorter latency periods before exploring the observation section of the pre-release enclosure, likely due to their naivety. This behavior indicates that age may influence initial exploration tendencies in a controlled environment, as observed in guinea pigs46and yellow-bellied marmots47. However, it is important to note that no correlation was found between age and the sequence order in which individuals approached the radio receivers during the post-release phase. This implies that while younger individuals may be quicker to explore initially, age does not appear to significantly affect their behavior in the post-release context. These insights underscore the complex interplay between age and exploratory behaviors, emphasizing the need for further investigation to fully understand the factors driving these patterns.

One month after their release, the WLPs began using an area of 0.02 km², gradually increasing their range to 2.4 km² over the course of a year. Nevertheless, they continued to frequent the vicinity of the pre-release enclosure. This result is consistent with the observations of Fragoso30, who recorded that WLP herds return regularly and predictably to their preferred feeding grounds. This natural behavior of the species persists even in sixth-generation animals in captivity, and it has increased the likelihood of individuals accessing both the provided food and water as well as the naturally available resources in the reintroduction site, which has contributed to their survival to date. The continued visitation of the area near the pre-release enclosure by the animals may be attributed to a potential association between this location and the anticipation of food provision, even in the absence of provision. Furthermore, during the PR, it was observed that the food provided in the conventional feeders was entirely consumed by the animals, with no evidence of leftovers or consumption by other species. This indicates that, although WLPs exhibited a pattern of increasing dispersal and a record of consuming natural foods, they continued to use supplementary feeding during the period in which it was offered.

To reduce dependence on the provided food supply, which has been verified previously (M. Figueira, personal communication, 2004), in the present study the supplementary food provision was suspended seven months after the animals were released (July 2023). This period coincided with the highest fruit supply in the region, from June to September74, thus ensuring the presence of fruit, which is the main food consumed by white-lipped peccaries in tropical rainforests75. The release site, situated at the Pau-Brazil Ecological Station, had previously been used as an experimental unit for the cultivation of fruit. The presence of animal traces at the site indicated that the animals were feeding on fruit in the forest plots with jackfruit and cupuaçu plantations. Although evidence of root consumption was also observed, it was not possible to identify the species consumed. Despite the continued provision of water in the water troughs in proximity to the enclosure throughout the PR, the animals exhibited a gradual cessation in their consumption of this resource, with minimal consumption recorded from the ninth month following their release. This suggests that, following the suspension of supplementary food provision, the artificially supplied water was no longer perceived as an attractive factor once natural water sources had been discovered. However, the study was conducted in a specific location (a remnant area of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest). The results might not be directly applicable to other regions or environmental contexts without further validation.

The white-lipped peccary is widely distributed across Central and South America, ranging from southeastern Mexico to northern Argentina35. Consequently, the Pau-Brazil Ecological Station, a remnant area of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest selected as the pre-release site, meets the ecological requirements of the species. Additionally, the pre-release site is located near the CETAS/IBAMA facility in Porto Seguro, Bahia, Brazil. The region experiences minimal human disturbances, ensuring a safe and stable environment for the pre-release process. Moreover, as previously described, the Pau-Brazil Ecological Station is well-connected to the Estação Veracel Private Nature Reserve. Together, these areas form a 72.3 km² fragment, promoting natural dispersal and increasing the likelihood of long-term population sustainability. Until 2018, the selected region historically supported the species57, making it a potentially suitable site for reintroduction. Furthermore, local communities have expressed strong support for the project, which is crucial for the successful implementation and long-term monitoring of the pre-release site. It is also important to note that the stable temperature and rainfall conditions in the region during the data collection period ensured that the behavior of the white-lipped peccaries remained unaffected by climatic factors during both the pre-release and post-release phases.

Two litters were observed during the PR phase, with one infant in each litter. This was corroborated by images captured by camera traps. According to Mayor et al.76, female peccaries typically have litters with one to two infants (with an average of 1.6 ± 0.5 infants per litter). Given that the gestation period of the species is approximately 158 days65, it can be inferred that the first litter was originally conceived while still on the premises of LABET/UESC during the PT phase. However, the second infant was conceived after the animals’ release from captivity. Beck et al.40 found that the five reintroductions that were successful in reintroducing mammals were with artiodactyls. Therefore, the positive results found herein were somewhat expected. Regrettably, the loss of ear tags used to identify the animals from a distance rendered it impossible to correlate the reproductive activity of females with their individual behavioral variation, creating a significant data gap. Therefore, future research should prioritize accurate animal identification to effectively capture long-term trends and variations in reproductive behavior and success. This will facilitate the extension of post-release monitoring to observe how individual behavioral traits influence long-term survival, reproduction, and integration into wild populations, providing deeper insights into the role of behavioral diversity in reintroduction success over an extended timeframe.

The findings of this study demonstrate that implementing a protocol involving temporal and spatial food unpredictability, coupled with classical conditioning and the use of a whistle for safe signaling, led to a notable increase in exploratory behavior, particularly in foraging activities within the natural habitat. This increase is likely to have contributed to the survival and reproductive success of reintroduced WLPs, indicating a relative achievement in their reintroduction efforts thus far. However, our study lacked a control group of WLPs that were not subjected to the pre-release training. This makes it difficult to ascertain the specific impact of the training on the observed outcomes. Moreover, the efficacy of the whistle in this context remains uncertain. In areas where reintroduced animals are afforded a certain level of protection, the whistle proved effective in facilitating the recapture of an injured animal. However, in other circumstances, the conditioning of attracting animals with the whistle can be exploited by illegal hunters. Consequently, prior to implementing this measure, a comprehensive evaluation of the potential safety concerns at the reintroduction site is essential.

In conclusion, the study highlights the importance of assessing the individual behavioral variation in predicting the behavior of WLPs within a reintroduction program. As anticipated, individuals exhibiting lower levels of sociability were observed to lead dispersal after release. Consequently, to enhance the probability of successful reintroduction, it is essential to devise pre-release training strategies that are specifically tailored to the behavioral traits of the individuals in question. For example, future research should test the efficacy of various behavioral interventions, such as socialization programs or specific training protocols, aimed at enhancing desirable traits like exploration and sociability. This approach could lead to more effective preparation of animals for release. Additionally, comparative studies across different species and habitats are recommended to determine the generalizability of the findings. Such studies could help develop species-specific reintroduction strategies and identify universal principles for improving reintroduction outcomes.

Data availability

Data AvailabilityThe data for this article are available via: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28311860.

References

Gosling, S. D. From mice to men: what can we learn about personality from animal research? Psychol. Bull. 127, 45–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.4 (2001).

Réale, D., Reader, S. M., Sol, D., McDougall, P. T. & Dingemanse, N. J. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. 82, 291–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00010.x (2007).

MacKay, J. R. D. & Haskell, M. J. Consistent individual behavioral variation: the difference between temperament, personality and behavioral syndromes. Animals 5, 455–478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani5030366 (2015).

Laskowski, K. L., Chang, C. C., Sheehy, K. & Aguiñaga J.Consistent individual behavioral variation: what do we know and where are we going? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 53, 161–182. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102220- (2022).

Smith, B. R. & Blumstein, D. T. Fitness consequences of personality: A meta-analysis. Behav. Ecol. 19, 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arm144 (2008).

Sih, A., Bell, A. & Johnson, J. C. Behavioral syndromes: an ecological and evolutionary overview. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.009 (2004).

Dingemanse, N. J. et al. Individual experience and evolutionary history of predation affect expression of heritable variation in fish personality and morphology. Proc. Royal Soc. B. 276, 1285–1293. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.1555 (2009).

Koolhaas, J. M. & Van Reenen, C. G. Animal behavior and well-being symposium: interaction between coping style/personality, stress, and welfare: relevance for domestic farm animals. J. Anim. Sci. 94, 2284–2296. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2015-0125 (2016).

Dall, S. R. X., Houston, A. I. & McNamara, J. M. The behavioural ecology of personality: consistent individual differences from an adaptive perspective. Ecol. Lett. 7, 734–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00618.x (2004).

Allard, S., Fuller, G., Torgerson-White, L., Starking, M. D. & Yoder-Nowak, T. Personality in zoo-hatched Blanding’s turtles affects behavior and survival after reintroduction into the wild. Front. Psychol. 10, 2324. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02324 (2019).

Herrera, C. M. Seed dispersal by vertebrates. In: Plant–Animal Interactions: an Evolutionary Approach, 1st edn. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford (ed Herrera, C. M.) (Pellmyr O.) 185–208. (2002).

Zwolak, R. How intraspecific variation in seed-dispersing animals matters for plants. Biol. Rev. 93, 897–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12377 (2018).

Merrick, M. J. & Koprowski, J. L. Should we consider individual behavior differences in applied wildlife conservation studies? Biol. Conserv. 209, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.01.021 (2017).

Bremner-Harrison, S. B., Prodohl, P. A. & Elwood, R. W. Behavioural trait assessment as a release criterion: boldness predicts early death in a reintroduction programme of captive-bred swift Fox (Vulpes velox). Anim. Conserv. 7, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1367943004001490 (2004). https://zslpublications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/

Watters, J. V. & Meehan, C. L. Different strokes: can managing behavioral types increase post-release success? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 102, 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.036 (2007).

Wilson, B. A. et al. Personality and plasticity predict post release performance in a reintroduced mesopredator. Anim. Behav. 187, 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2022.02.019 (2022).

Wu, X. Y., Lloyd, H., Dong, L., Zhang, Y. Y. & Lyu, N. Moving beyond defining animal personality traits: the importance of behavioural correlations and plasticity for conservation translocation success. Glob Ecol. Conserv. e02784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2023.e02784 (2023).

Newberry, R. C. Environmental enrichment: increasing the biological relevance of captive environments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 44, 229–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(95)00616-Z (1995).

Silva, R. S. et al. Temperament assessment and pre-release training in a reintroduction program for the turquoise-fronted Amazon Amazona aestiva. Acta Ornithol. 55, 199–214. https://doi.org/10.3161/00016454AO2020.55.2.006 (2020).

Nogueira, S. S. C., Calazans, S. G., Costa, T. S. O., Peregrino, H. & Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G. Effects of varying feed provision on behavioral patterns of farmed collared peccary (Mammalia, Tayassuidae). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 132, 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2011.04.002 (2011).

Nogueira, S. S. C., Abreu, S. A., Peregrino, H. & Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G. The effects of feeding unpredictability and classical conditioning on pre-release training of white-lipped peccary (Mammalia, Tayassuidae). PLoS ONE. 9, e86080. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086080 (2014).

Beck, H., Thebpanya, P. & &Filiaggi, M. Do Neotropical peccary species (Tayassuidae) function as ecosystem engineers for anurans? J. Trop. Ecol. 26, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467410000106 (2010).

Keuroghlian, A. et al. Avaliação do Risco de extinção do Queixada Tayassu pecari link, 1795, no Brasil. BioBrasil 2, 84–102 (2012).

Keuroghlian, A. et al. Tayassu pecari. IUCN Red List. Threatened Species. e.T41778A44051115 https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T41778A44051115.en (2013). Accessed 12 January 2023 (2013).

Oshima, J. E. et al. Setting priority conservation management regions to reverse rapid range decline of a key Neotropical forest ungulate. GEC 31, e01796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01796 (2021).

Norris, D. et al. How to not inflate population estimates? Spatial density distribution of white-lipped peccaries in a continuous Atlantic forest. Anim. Conserv. 14, 492–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2011.00450.x (2011).

Canale, G. R. et al. Pervasive defaunation of forest remnants in a tropical biodiversity hotspot. PLoS ONE 7(8): (2012). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone. 0041671 PMID: 22905103.

Mendes Pontes, A. R. et al. Mass extinction and the disappearance of unknown mammal species: scenario and perspectives of a biodiversity hotspot’s hotspot. PLoS One. 11, e0150887. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150887 (2016).

Fragoso, J. M. V. et al. Large-scale population disappearances and cycling in the white-lipped peccary, a tropical forest mammal. PLoS ONE. 17, e0276297. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276297 (2022).

Fragoso, J. M. V. Home range and movement patterns of white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) herds in the Northern Brazilian Amazon. Biotropica 30, 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.1998.tb00080.x (1998).

Fragoso, J. M. V. A long-term study of white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) population fluctuations in Northern Amazonia: anthropogenic vs.natural causes. In (eds Silvius, K., Bodmer, R. & Fragoso, J. M. V.) People in Nature: Wildlife Conservation in South and Central America, 1st edn. Columbia University, 286–296 (2004).

Silman, M. R., Terborgh, J. W. & Kiltie, R. A. Population regulation of a dominant rain forest tree by a major seed predator. Ecology 84, 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084 (2003). [0431:PROADR]2.0.CO;2.

Keuroghlian, A., Eaton, D. P. & Longland, W. S. Area use by white-lipped and collared peccaries (Tayassu pecari and Tayassu tajacu) in a tropical forest fragment. Biol. Conserv. 120, 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.016 (2004).

Galetti, M. et al. Diet overlap and foraging activity between feral pigs and native peccaries in the Pantanal. PLoS ONE. 10, e0141459. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141459 (2015).

Altrichter, M. et al. White-lipped Peccary Tayassu pecari. In: Ecology, conservation and management of wild pigs and peccaries, 1st edn. Cambridge UniversityPress (eds Meletti M. & Meijaard E.) 191–207. (2017).

Flores-Turdera, C., Ayala, G., Viscarra, M. & Wallace, R. Comparison of big Cat food habits in the Amazon Piedmont forest in two Bolivian protected areas. Therya 12, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.12933/THERYA-21-1024 (2021).

Whitworth, A. et al. Disappearance of an ecosystem engineer, the white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari), leads to density compensation and ecological release. Oecologia 199, 937–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-022-05233-5 (2022).

Moseby, K. E., Hill, B. M. & Lavery, T. H. Tailoring release protocols to individual species and sites: one size does not fit all. PLoS One. 9, e99753. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099753 (2014).

Soorae, P. S. Global re-introduction Perspectives: Additional case-studies from around the Globe (IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group, 2010).

Beck, B. B., Stanley, P. M. R., Rapaport, L. G. & Wilson, A. C. Reintroduction of captive-born animals. In: Creative Conservation: Interactive Management of Wild and Captive Animals. Chapman & Hall, London (eds Olney, P. J. S., Mace, G. M. & Fleistner) 265–286. (1994).

Bright, P. W. & Morris, P. A. Animal translocation for conservation: performance of dormice in relation to release methods, origin and season. J. Appl. Ecol. 31, 699–708. https://doi.org/10.2307/2404160 (1994).

Figueira, M. D. L. D. O. A., Carrer, C. R. O. & Silva Neto, P. B. Ganho de peso e evolução do Rebanho de Queixadas Selvagens Em Sistemas de Criação semi-extensivo e extensivo, Em reserva de Cerrado. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 1, 191–199 (2003).

Instituto Água e Terra. Projeto no Parque das Lauráceas visa reforçar população dos mamíferos queixada e cateto. Secretaria do Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Governo do Paraná. January (2023). https://web.archive.org/web/20240407211041/https://www.iat.pr.gov.br/Noticia/Projeto-no-Parque-das-Lauraceas-visa-reforcar-populacao-dos-ma. Accessed 10 (2022).

Nogueira, S. S. C., Macêdo, J. F., Sant’Anna, A. C. & Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G. Paranhos Da Costa, M.J.R. Assessment of temperament traits of white-lipped (Tayassu pecari) and collared peccaries (Pecari tajacu) during handling in a farmed environment. Anim. Welf. 24, 291–298. https://doi.org/10.7120/09627286.24.3.291 (2015).

Budzyńska, M., Kamieniak, J., Krupa, W. & Sołtys, L. Behavioral and physiological reactivity of mares and stallions evaluated in performance tests. Acta Vet. -Beograd. 64, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.2478/acve-2014-0031 (2014).

Guenther, A. Life-history trade-offs: are they linked to personality in a precocial mammal (Cavia aperea)? Biol. Lett. 14, 20180086. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0086 (2018).

Petelle, M. B., McCoy, D. E., Alejandro, V., Martin, J. G. & Blumstein, D. T. Development of boldness and docility in yellow-bellied marmots. Anim. Behav. 86 (6), 1147–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.09.016 (2013).

Réale, D., Gallant, B. Y., Leblanc, M. & Festa-Bianchet, M. Consistency of temperament in Bighorn Ewes and correlates with behaviour and life history. Anim. Behav. 60, 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2000.1530 (2000).

Ray, J. & Hansen, S. Temperamental development in the rat: the first year. Dev. Psychobiol. 47, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20080 (2005).

Wirth-Dzięciołowska, E., Lipska, A. & Węsierska, M. Selection for body weight induces differences in exploratory behavior and learning in mice. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 65, 243–253 (2005).

Nogueira, S. S. C. et al. The defensive behavioral patterns of captive white-lipped and collared peccary (Mammalia, Tayassuidae): an approach for conservation of the species. Acta Ethol. 20, 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10211-017-0256-5 (2017).

Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G., Nogueira, S. S. C. & Sato, T. A estrutura social de Pecaris (Mammalia, Tayassuidae) Em Cativeiro. Rev. Etol. 1, 89–98 (1999).

Dubost, G. Comparison of the social behaviour of captive sympatric peccary species (genus Tayassu); correlations with their ecological characteristics. Mamm. Biol. 66, 65–83 (2001).

Nogueira, S. S. C., Soledade, J. P., Pompéia, S. & Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G. The effect of environmental enrichment on play behaviour in white-lipped peccaries (Tayassu pecari). Anim. Welf. 20, 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962728600003146 (2011).

Leonardo, D. E. et al. Third-party conflict interventions are kin biased in captive white-lipped peccaries (Mammalia, Tayassuidae). Behav. Process. 193, 104524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2021.104524 (2021).

Porter, B. A. & Texas Evaluation of collared peccary translocations in the Texas hill country. A & M University, College Station, Texas (2006).

Magioli, M., Morato, R. G. & de Camargos, V. L. Mammals from biodiversity-rich protected areas in the Brazilian discovery Coast. Braz J. Mammal. 91, e91202273. https://doi.org/10.32673/bjm.vi91.73 (2022).

Novais, G. Climas do Brasil: classificação climática e aplicações (1a). Totalbooks. (2023).

Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G., Borges, R. M., Mendes, A. & Dias, C. T. S. Nitrogen requirements of white-lipped peccary (Mammalia, Tayassuidae). Zoo Biol. 33, 320–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21141 (2014).

Lazure, L., Bachand, M., Ansseau, C. & Cortez, A. Fate of native and introduced seeds consumed by captive white-lipped and collared peccaries (Tayassu pecari, link 1795 and Pecari tajacu, Linnaeus 1758) in the Atlantic rainforest. Brazil Braz J. Biol. 70, 47–53 (2010).

Silva, R. et al. Manejo e alimentação de Caitetus (Tayassu tajacu) e Queixadas (T. pecari) Em Cativeiro Na Amazônia central. REMFAUNA 1, 1–31 (2009).

Altmann, J. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour 49, 227–266 (1974).

Friard, O. & Gamba, M. BORIS: a free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1325–1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12584 (2016).

Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics 5th edn (SAGE Publications Ltd., 2013).

Sowls, L. K. & Texas, A. Javelinas and other peccaries: their biology, management, and use. & M University, College Station, Texas (1997).

Dodge, Y. Coefficient of variation. In: The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics. Springer, New York, NY. 95–96 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-32833-1_65 (2008).

McDougall, P. T., Réale, D., Sol, D. & Reader, S. M. Wildlife conservation and animal temperament: causes and consequences of evolutionary change for captive, reintroduced, and wild populations. Anim. Conserv. 9, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2005.00004.x (2006).

Frankham, R. et al. Selection in captive populations. Zoo Biol. 5, 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.1430050207 (1986).

Christie, M. R., Marine, M. L., French, R. A. & Blouin, M. S. Genetic adaptation to captivity can occur in a single generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 109, 238–242. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.111107310

Peignier, M. et al. Space use and social association in a gregarious ungulate: testing the conspecific attraction and resource dispersion hypotheses. Ecol. Evol. 9, 5133–5145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2018.05.023 (2018).

Gartland, L. A., Firth, J. A., Laskowski, K. L., Jeanson, R. & Ioannou, C. C. Sociability as a personality trait in animals: methods, causes and consequences. Biol. Rev. 97, 802–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12823 (2022).

Ojasti, J. Wildlife Utilization in Latin America: Current Situation and Prospects for Sustainable Management. FAO Conservation Guide 25 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1996).

Laundré, J. W., Hernández, L. & Altendorf, K. B. Wolves, elk, and Bison: reestablishing the landscape of fear in Yellowstone National park, USA. Can. J. Zool. 79, 1401–1409. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-79-8-1401 (2001).

Catenacci, L. S., Pessoa, M. S., Nogueira-Filho, S. L. G. & De Vleeschouwer, K. M. Diet and feeding behavior of Leontopithecus chrysomelas (Callitrichidae) in degraded areas of the Atlantic forest of South-Bahia, Brazil. Int. J. Primatol. 37, 136–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-016-9889-x (2016).

Kiltie, R. A. Stomach contents of rain forest peccaries (Tayassu Tajacu and T. pecari). Biotropica 13, 234–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388133 (1981).

Mayor, P., Bodmer, R. E. & Lopez-Bejar, M. Reproductive performance of the wild white-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) female in the Peruvian Amazon. Eur. J. Wildl. 55, 631–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-009-0312-1 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the information provided by Maria de Lourdes de Oliveira Andrade Figueira in 2004. The authors Sérgio Nogueira-Filho and Selene Nogueira received support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) during the study (Processes # 304593/2022-2 and # 303320/2022-2, respectively). This study was financed in part by the National Institute of Science and Technology in Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Studies in Ecology and Evolution (IN-TREE – Process National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) #465767/2014-1 and Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES) #23038.000776/2017-54), Bahia, Brazil.

Funding

The authors Sérgio Nogueira-Filho and Selene Nogueira received support from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) during the study (Processes # 304593/2022-2 and # 303320/2022-2, respectively). This study was financed in part by the National Institute of Science and Technology in Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Studies in Ecology and Evolution (IN-TREE – Process National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) #465767/2014-1 and Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (CAPES) #23038.000776/2017-54), Bahia, Brazil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study conception and design were made by S. Nogueira. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by C. Cavalcante Neto, L. Ilg, A. Nogueira, and S. Nogueira-Filho. The first draft of the manuscript was written by C. Cavalcante Neto and L. Ilg, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals (CEUA)/ State University of Santa Cruz (UESC) (#037/20) and Biodiversity Authorization and Information System (SISBIO) (#8741). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neto, C.J.T.C., Nogueira-Filho, S.L., Nogueira, A.L.G. et al. Impact of behavioral differences on white-lipped peccary reintroduction success in the Atlantic forest. Sci Rep 15, 7705 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90853-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90853-z