Abstract

Multimodal image feature matching is a critical technique in computer vision. However, many current methods rely on extensive attention interactions, which can lead to the inclusion of irrelevant information from non-critical regions, introducing noise and consuming unnecessary computational resources. In contrast, focusing attention on the most relevant regions (information-rich areas) can significantly improve the subsequent matching phase. To address this, we propose a feature matching method called FmCFA, which emphasizes critical feature attention interactions for multimodal images. We introduce a novel Critical Feature Attention (CFA) mechanism that prioritizes attention interactions on the key regions of the multimodal images. This strategy enhances focus on important features while minimizing attention to non-essential ones, thereby improving matching efficiency and accuracy, and reducing computational cost. Additionally, we introduce the CFa-block, built upon CF-Attention, to facilitate coarse matching. The CFa-block strengthens the information exchange between key features across different modalities. Extensive experiments demonstrate that FmCFA achieves exceptional performance across multiple multimodal image datasets. The code is publicly available at: https://github.com/LiaoYun0x0/FmCFA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Feature matching has been an important research direction in computer vision, especially feature matching between multimodal images1,2,3. Multimodal images include optical images, near-infrared(NIR) images, depth images, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) images, short-wave infrared(SWIR) images, and so on. Many image processing tasks in computer vision need to be realized on the basis of feature matching, such as: image fusion4,5,6, image matching7,8, image retrieval9, image classification10,11 and image embedding12. Due to the complementary information contained in images of different modalities, it is necessary to find an efficient and robust feature matching method for multimodal images. Further, the existing mainstream feature matching methods can be mainly categorized into two types: detector-based methods and detector-free methods.

Detector-based local feature matching methods mainly rely on the use of convolutional neural networks to learn detectors or extract local descriptors. Depending on the means of generating descriptors, detector-based local feature matching methods can be generally categorized into three main groups: handcrafted feature descriptor methods, area-based descriptor generation methods, and learning-based feature descriptor methods. Handcrafted feature descriptor methods13,14,15 mainly rely on human efforts to design and generate effective local feature descriptors by utilizing relevant techniques in the field of computer vision, and furthermore, establish correct correspondences based on spatial geometry knowledge. The area-based method16,17,18 of generating descriptors achieves image feature matching by measuring the similarity between pixels after domain transformation, which makes it possible to achieve good results when the image details are less. However, the performance of the region-based descriptor generation method is poor when there is a high intensity of transformations between image pairs. Learning-based feature descriptor generation methods19,20,21 learn feature information9 through neural networks to generate good feature descriptors. Detector-based methods are generally two-stage approaches, i.e., a keypoint detector is required to detect the keypoints first, and then the feature descriptors are extracted based on the locations of the keypoints. Because of the dependence on the keypoint detector and the correct detection of keypoints directly affects the subsequent matching results, traditional detector-based methods tend to have large errors.

The Detector-free local feature matching method tends to have better matching results than the detector-based local feature matching method, which is a one-stage method unlike the detector-based two-stage method, i.e., it does not need to rely on a keypoint detector but uses pixel-level dense matching to select keypoints. The dense matching approach reduces the matching errors caused by keypoint detection. Transformer was initially proposed in the field of natural language processing (NLP)22. Due to the excellent global modeling capability of transformer, more and more researchers have also incorporated transformer into detector-free local feature matching methods. Numerous studies232425 have shown the importance of implementing intensive global attention interactions in feature matching. However, this interaction does not distinguish between critical and non-critical regions. Undoubtedly, attention information interaction in non-critical regions will introduce noise to affect the subsequent matching effect. In contrast, grasping the key local features can make the feature matching twice as effective with half the effort. At the same time, due to the information variance between the pairs of images to be matched, it is undoubtedly a waste of computational resources to carry out information interaction on some unimportant features. Therefore, for feature matching, if the global information interaction can be focused on ctrtical features while having local information interaction, it will greatly improve the matching efficiency and accuracy.

To address the aforementioned challenges, we propose a novel multimodal image feature matching method, FmCFA. FmCFA integrates both local and global attention interactions effectively. We introduce a new attention mechanism, CF-Attention, which focuses attention interactions on critical features, thereby reducing the computational load of global attention while enhancing matching efficiency and accuracy. Additionally, we propose the CFa-Block, which combines window attention, CF-Attention, and cross-attention. The CFa-Block facilitates coarse-grained information interaction between features. As shown in Fig. 1, extensive experiments demonstrate that FmCFA outperforms existing methods in terms of matching accuracy on multimodal image datasets.

Related work

Due to the complementary information between multimodal images, designing an excellent feature matching method for multimodal images in becomes especially important for many computer vision studies or applications. And the feature matching technique is the most crucial part of it. Recent studies can categorize feature matching methods into two types: detector-based methods and detector-free methods.

Detector-based local feature matching methods

Detector-based methods are the classical methods for feature matching, which can be roughly classified into three categories according to the different ways of extracting feature descriptors: handcrafted feature descriptor methods, area-based descriptor generation methods and learning-based feature descriptor methods.

-

1.

Handcrafted feature descriptor methods: As early as 2004, a classical manual descriptor called Scale-invariant feature transform13 was proposed and used for feature matching. Fu et al.14 in 2019, generated a feature descriptor by combining texture and structural information corresponding to normalized feature vectors. In 2021, Cheng et al.15 proposed a binary-based feature descriptor which is used to retrieve missing features when performing image feature matching.

-

2.

Area-based descriptor generation methods: A feature descriptor with dense local self-similarity and defining similarity metrics based on this descriptor was proposed by Ye et al16. In 2020, Xiong et al.17 generated a feature descriptor based on ranked local self-similarity, which contains local features with high image discriminability. In 2021, a novel local feature descriptor based on discrete cosine transform was proposed by Gao et al.18. It can efficiently and compactly maintain the local information and thus achieved good results.

-

3.

Learning-based feature descriptor methods: In 2020, the classical SuperGlue19 was proposed. SuperGlue estimates the allocation by predicting the cost of the optimal transportation problem via graph neural networks and performs contextual aggregation based on attention. Ma et al20, in 2021, processed multispectral images by generative adversarial network with regularization condition to solve the problem of features between multispectral images. In 2022, GLMNet21 solves the graph matching problem by graph learning network while proposing a new constrained regularization loss on top of Laplace sharpened graph convolution.

Detector-free local feature matching methods

Detector-free methods are one-stage feature matching methods using dense matching implemented pixel by pixel. In 2020, a fully microscopic dense matching in GOCor26 was proposed by Truong et al. as an alternative to the feature correlation layer, which efficiently learns the spatial matching prior. In 2021, Prune Truong et al.27 computed the dense flow field between two images, and then showed the accuracy and reliability of the predictions through a pixel-by-pixel confidence map. Further, they parameterized the prediction distribution into a constrained mixture model to more accurately model flow predictions and outliers. The DualRC-Net28 proposed by Li et al. introduces a dual-resolution correspondence network and obtains pixel-level correspondences by a coarse-to-fine method. Based on this, DualRC-Net improves the accuracy and precision of matching. Sun et al.23 , in 2021, proposed a local feature matching method (LoFTR), which is based on the Transformer. LoFTR first establishes pixel-level dense matching on the basis of a coarse feature map and obtains the coarse matching results. Further, the coarse matching result is adjusted on the fine feature map to obtain the final matching result.

Vision transformer

The rise of the Transformer model began in the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and, due to its exceptional ability to capture global information, has led to the development of numerous transformer-based approaches in various areas of computer vision, including but not limited to semantic segmentation29,30, object detection31,32, and image classification33,34. Similarly, many researchers have applied Transformers to the field of feature matching. For example, LoFTR23 utilizes self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms to perform coarse-grained local transformer interactions on intra-image and inter-image pairs. FeMIP24 leverages the Vision Transformer for multimodal image feature matching and has achieved impressive results across multiple modality datasets. While these methods employ Transformers to address image feature matching, they mainly focus on extracting attention from global features. In contrast, our proposed FmCFA method distinguishes key regions in multimodal images and applies Transformers to capture critical attention on these important features. This approach not only reduces computational cost but also enhances both matching efficiency and accuracy.

The overview of FmCFA. \(x_{q}\) denotes the query image and \(x_{r}\) denotes the reference image. During feature extraction, feature maps of 1/8 and 1/2 sizes are generated. The 1/8 size features are used for coarse matching, while the 1/2 size features are used for fine matching. In the coarse matching phase, the Critical Features Interaction module is applied to enhance attention on coarse-level features, which are then further refined by matching them with the 1/2 size features for fine matching. Finally, the resulting matched features are used to produce the final feature matching.

Methods

A general overview of our proposed FmCFA is shown in Fig. 2. FmCFA is a one-stage detector-free feature matching method, where the input is a pair of images denoted as \(x_q\) and \(x_r\). \(x_q\) denotes the query image and \(x_r\) denotes the reference image. They represent a pair of images of different modals. Firstly, the feature extractor (“Feature extraction”) is used to extract initial features from images \(x_q\) and \(x_r\), resulting in a coarse-grained feature map at 1/8 of their original size and a fine-grained feature map at 1/2. The initial 1/8 coarse-grained feature map is then passed into our proposed critcal feature interaction module (“Critical feature attention block”). This module consists of several critical feature attention blocks stacked together (“Critical feature attention”). After that, in order to achieve critical region attention interaction while effectively reducing the computation of global attention, the critical feature attention block is designed as a feature fusion augmentation block consisting of window attention, CF-Attention (“Coarse level matching module”) and cross-attention together . The initial 1/8 coarse-grained feature map undergoes the critical feature interaction module and the attention-enhanced coarse-level feature is obtained. Further, we implement dense matching on the basis of the coarse-grained feature map to obtain coarse matching results. Finally, on the basis of the fine-grained feature map, pixel-level refinement regression is performed in regions where the probability of coarse matching is greater than a given threshold.

Preliminary

Attention

Attention mechanism excels in capturing long-distance dependencies. Suppose an input X, three transformation matrices query (Q), key (K) matrix and value (V) matrix are generated by linear transformations of X. The matrix is generated by a linear transformation of X. The matrix is a matrix with a key (K) and a value (V). The computation and output of attention can be realized based on the three matrices:

where \(W_Q\), \(W_K\) and \(W_V\) are learned weight matrices used to transform the input sequence X into a matrix of queries, keys and values. d is the dimensionality of the queries and keys.

Linear attention

Although the attention mechanism has excellent global modeling capabilities, it introduces a large computational complexity. The linear attention mechanism was proposed by Linear Transformer35, which achieves the same excellent results while having a lower computational complexity. The following is the formulation of the linear attention:

where \(k_{j}\) is the jth keywork vector in K.

where \(elu(\cdot )\) denotes the exponential linear unit activation function.

Window attention

Window attention allows the model to focus on more localized information when processing inputs(x). The model considers only the interrelationships between the positions in the input sequence and the current position within the window size, and does not compute global self-attention. Localized windows segment the image uniformly in a non-overlapping manner, and self-attention operations are performed within each window:

where B denotes batch size, H and W denote the height and width of input x, C denotes the number of channels and w denotes the window size. We define \(nw=\frac{H \times W}{w \times w}\). The function win_Partition performs a non-overlapping partition of the input feature map. The size of the partition window is w\(\times\)w, then the shape of the output feature map is \((B \times nw ) \times w \times w \times c\).

where the function win_merge merges the set of windows whose feature maps are of shape \((B \times nw ) \times w \times w \times c\) into a \(B \times H \times W \times C\) feature map.

The above window attention process can be summarized as:

Feature extraction

In the initial feature extraction phase, we adopt a UNet-like36 network structure that utilizes the middle layer of the ResNet37, to go about extracting features. Before inputting images to the network, the image pairs are resized to 320\(\times\)320. The input is represented as \(x_q\) and \(x_r\). 1/8 size feature maps denoted as \(x_q^c\) and \(x_r^c\) are extracted by the intermediate layer of the ResNet37. The fine-grained level feature maps, denoted as \(x_q^f\) and \(x_r^f\) are continually derived from the coarse-grained ones by a series of convolutional, up-sampling and fusion operations.

Critical feature attention block

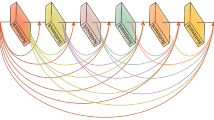

Due to the information variability of multimodal images, it is inevitable that information is interacted between useless features during global transformer interaction. The information interaction between useless features will waste computational resources and have a negative impact on the subsequent matching process. As shown in Fig. 3, the orange area represents critical features and the green area represents non-critical features. It is obvious that the features under the orange region are rich in information. Attention interaction on such features will bring more benefits to the keypoint finding and matching process. On the other hand, the features within the green region do not possess much critical information. This useless information will undoubtedly hinder the keypoint extraction and matching process. Therefore, it is undeniable that focusing the attention interaction on critical fatures as much as possible will improve the accuracy and efficiency of matching under multimodal images.

The overview of critical feature attention block (CFa-Block). In the Critical Feature Attention block, the 1/8 size feature map first extracts window attention. Then, Critical Features Residual (CFR) is applied to obtain Critical Feature attention. Following this, cross-attention is computed between the images from the two modalities to generate a coarse match.

Besides, although some methods can perform local attention interactions at the coarse level, these interactions are completed on the entire coarse feature map, which lacks understanding of information within a certain region. Images are usually composed of various local features, such as edges, textures, corners, etc. These local features are crucial for object recognition and matching. Further, an object usually consists of multiple local parts. The relative positions and relationships between these local parts are important for matching. The local information interaction within the region can be very helpful for the model to understand the relationship between different parts to achieve better matching results.

Based on the above viewpoint, we propose a new block of attention interactions called CFa-Block. With the expectation that the model can focus global information interaction on critical fatures while having the ability to interact with local information. Further, we apply it within the coarse level feature transformer module.

The inputs to the critical feature interaction module are the coarse-grained feature maps (\(x_q^c \in R^{B \times H \times W \times C}\) and \(x_r^c \in R^{B \times H \times W \times C}\)). Assume that the size of the division window is w and the number of critical fatures selected inside each window is k. \(x_q^c\) and \(x_r^c\) are first partitioned into features in non-overlapping window format and self-attention interactions are performed within each window:

where \(x_q^{cw} \in R^{B \times H \times W \times C}\) and \(x_r^{cw} \in R^{B \times H \times W \times C}\). nw denotes the number of windows.

The outputs \(x_q^{cw}\) and \(x_r^{cw}\) after window attention are passed through CF-Attention. CF-Attention, critical features attention mechanism, focuses the attention interactions on the critical fatures we have selected to avoid the introduction of noise from non-important features. We will describe CF-Attention in detail in “Critical feature attention”.

where \(x_q^{cf} \in R^{B \times ( nw \times k) \times C}\) and \(x_r^{cf} \in R^{B \times ( nw \times k) \times C}\).

Finally, \(x_q^{cf}\) and \(x_r^{cf}\), after format conversion, perform information interaction between image pairs based on cross-attention. For cross-information interactions between image pairs, Q is generated from one image, while K and V are obtained from another. Cross-attention interactions are also realised by linear attention:

where \(Q_q\), \(K_q\) and \(V_q\) are obtained from \(x_q^{cf}\) by linear projection. \(Q_r\), \(K_r\) and \(V_r\) are obtained from \(x_r^{cf}\) by linear projection. This process of cross-attention interaction can be summarised as follows:

Here, we do not implement cross-attention on critical fatures but keep the global cross-information interaction for the whole coarse feature map. Because of the large difference in information between different modal image pairs, the combination of critical fatures disrupts the feature information and location information to some extent. In this case, implementing cross-attention only on important features leads to information disorder. This is detrimental to the cross-information interaction between different modal images and the subsequent matching process.

All of the above processes can be summarised as follows:

We use CFa-Block to represent all the above operations:

\(x_q^e\) and \(x_r^e\) represent the final output. The overview flow of CFa-Block is shown in Figure 4. Our coarse level feature transformer module consists of iterating the CFa-Block N times.

Critical feature attention

Our proposed CF-Attention aims to enable the model to focus attention on critical fatures thus improving the matching accuracy. The overall flow of CF-Attention is shown in Fig. 5. CF-Attention is described in detail in this section.

Critical features selection (CFS)

The process of selecting critical features in CF-Attention is demonstrated as shown in Fig. 6. The input to CF-Attention is the output of the window attention, denoted as \(x_q^{cw} \in R^{(B \times nw) \times w \times w \times C}\) and \(x_r^{cw} \in R^{(B \times nw) \times w \times w \times C}\) . Firstly, the average pooling operation is performed for each window to obtain the representative features inside each window:

where \(x_{q1} \in R^{(B \times nw) \times 1 \times C}\) and \(x_{r1} \in R^{(B \times nw) \times 1 \times C}\). \(x_{q1}\) and \(x_{r1}\) denote the representative features of each window for \(x_q^{cw}\) and \(x_{r1}\), respectively.

Next, all features within each window are computed for similarity with the represented feature of that window, and then the similarity scores are normalised to obtain the corresponding similarity matrix for each window:

Based on the similarity scores, we select the k index locations with the highest scores. Based on the index position, k features are selected as critical fatures inside each window.

Note that the shapes of \(k_q\) and \(k_r\) are \(R^{(B \times nw) \times k \times C}\). The above process is summarised as:

Cretical features interaction (CFI)

The critical fatures inside each window(\(k_q\) and \(k_r\)) are combined to form all the critical fatures of each image. The shapes of \(k_q\) and \(k_r\) are transformed into \(R^{B \times (nw \times k) \times C}\). All of these critical fatures achieve attention interaction between important regions through linear attention:

\(Q_{k_q}\), \(K_{k_q}\), and \(V_{k_q}\) are obtained from \(k_q\) by linear projection. Relatively, \(Q_{k_r}\), \(K_{k_r}\), and \(V_{k_r}\) are generated according to \(k_r\). \(k_{q2} \in R^{B \times ( nw \times k) \times C}\) and \(k_{r2} \in R^{B \times ( nw \times k) \times C}\) are the outputs of CF-Attention.

Cretical features residual (CFR)

The outputs \(k_{q2}\) and \(k_{r2}\) after CFI are residualised with the inputs(\(x_q^{cw}\) and \(x_q^{cf}\)). \(k_{q2}\) and \(k_{r2}\) are done fusion with the input features based on the index position. This process is denoted as CFR:

where the shapes of \(x_q^{cf}\) and \(x_r^{cf}\) have been transformed into \(R^{(B \times nw) \times k \times C}\).

Finally, all of the above processes can be summarised as:

Coarse level matching module

We use the same policy gradient-based reward and punishment strategy as FeMIP24 for training supervision of the coarse matching module. A series of correspondences are established based on the augmented features \(x_q^e\) and \(x_r^e\) after attention interaction. A bidirectional softmax operation is then used to obtain the probability of nearest neighbour matching in both directions, which can be defined as:

where S is a confidence matrix based on the correspondence and P represents the matching probability.

Further, if the sample is a positive sample in the ground truth matrix and the match probability P is greater than a given threshold u, we consider the match to be correct and give it a positive reward \(\alpha\). In contrast, if the sample is a negative sample and the match probability P is less than u, we do not give it a reward. In all other cases we consider the match to be incorrect and give a negative reward \(\beta\). The value of \(\beta\) is set according to the number of training epochs(n) in order to train the network smoothly:

The policy gradient formula is as follows:

where \(M_{q \leftrightarrow r}\) represents the correspondence and \(P(i \leftrightarrow j | x_q^e,x_r^e)\) is the distribution of matches between \(x_q^e\) and \(x_r^e\). \(\nabla _{\theta \phi _{ij}}\) is the logarithmic gradient of the action sequences. And \(\phi _{ij}\) represents the three motion sequences: \(x_q^e\) from \(x_q\), \(x_r^e\) from \(x_r\), and establishing a match between \(x_q^e\) and \(x_r^e\).

Finally, the loss function for coarse level matching can be expressed as:

where t is the given confidence threshold.

Fine level regression re-fine

The results of coarse matching are based on 1/8 coarse feature maps, which results in them not being accurate. Therefore, we use regression to regress the feature maps with high accuracy so that our method can perform accurate pixel-level matching. Similarly to FeMIP24, we employ the same implementation approach.

Specifically, when dealing with each pair of coarse-level matching results, we map their coordinates onto the fine-level feature map \({x_q^f, x_r^f}\) and extract two sets of local feature windows. Then, we extract two collections of local feature windows for each pair of coarse-level matching results. These windows are then utilized to blend the coarse-level and fine-level feature maps, resulting in the creation of fused feature maps denoted as: \(x_q^{fc},x_r^{fc}\)

Subsequently, the fused feature maps \(x_q^{fc},x_r^{fc}\) are passed through an interaction module, which comprises self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms. This interaction module refines the feature maps and produces the refined feature maps \(x_{qA}^{fc},x_{rA}^{fc}\).

Ultimately, the refined fine-level matching results are obtained through regression using a fully connected layer. We determine the outcome of fine regression, denoted as \((\nabla x, \nabla y)\), by calculating the difference between the predicted coordinates \((i_p, j_p)\) and the actual coordinates \((i_a, j_a)\).

The loss of the fine regression re-fine module can be defined as:

where m is the number of feature points, \(\nabla x\) and \(\nabla y\) are the difference between the horizontal and vertical coordinate positions obtained from the fine regression, respectively.

Our total loss is defined as:

where \(\delta _1\) and \(\delta _2\) denote the weights of the two losses L1 and L2, respectively.

Experiment

Implementation details

We use AdamW with CosineAnnealingLR to train the model. The learning rate is \(1 \times 10^{-3}\) and the batch size is 4. The value of t is taken to be 0.2. \(\delta _1\) and \(\delta _2\) are both set to 1. The training is performed on an Nvidia RTX 3090 GPU.

Dataset

We selected five multimodal datasets to validate our model. These multimodal image types include RGB, depth, optical, near-infrared, synthetic aperture radar (SAR), and short-wave infrared (SWIR) images.

-

(1)

SEN12MS: The dataset SEN12MS38 provides multiple modalities of an image. Therefore, we perform validation between many different modalities on this dataset.The SEN12MS dataset has multimodal images including RGB, SAR, NIR, and SWIR images. We selected 16000 pairs of images for training and 600 pairs of images for testing.

-

(2)

Optial-SAR: The optical-sar dataset39 is an important benchmark dataset for multimodal image feature matching. This dataset includes a variety of scenes: plains, harbors, airports, cities, islands, and rivers. The image size of this dataset is 512\(\times\)512. where we select 16,000 pairs of images for training and 500 pairs of images for testing.

-

(3)

WHU-OPT-SAR: The WHU-OPT-SAR dataset40 contains the following scene categories: farmland, deep forest, road, village, water and city. It was collected in Hubei Province, China. Since the size of the original images of the dataset is too large, we crop it to generate 4400 pairs of images. Among them, we randomly selected 3800 pairs of images for training, 300 pairs of images for validation, and the remaining 300 pairs for testing.

-

(4)

RGB-NIR scene: The RGB-NIR Scene41 contains 477 image pairs consisting of RGB and NIR images. It contains 9 scenes: countryside, street, field, forest, mountain, water, city, indoor and old building. Among them, we choose 400 pairs of images from this dataset for training and 48 pairs of images for testing.

-

(5)

NYU-Depth V2: The NYU-Depth V2 dataset42 is captured from video sequences of indoor scenes. 1449 pairs of RGB and depth images are densely labeled and pairs of them. We select 1049 pairs of images for training and 400 pairs for testing.

Baseline and metrics

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our proposed method in feature matching on multimodal graph datasets, we compared it with several other excellent methods: FeMIP24, LoFTR23, LNIFT43, HardNet44, TFeat45, MatchosNet46, and MatchNet47. We train and test different methods in the same environment, training set, and testing set, and evaluate them using the same evaluation indicators. The evaluation indicators are as follows:

Homography estimation

Homography estimation is computed using OpenCV and further RANSAC is used as robust estimation. In this, the correct identifier is calculated based on the angular error between the predicted result and the groundtruth. We compute the average reprojection error for the four corners of the image and report the regions under the cumulative curve(AUC)48 where the angular error reaches different thresholds (@3 px, @5 px and @10 px).

Mean matching accuracy (MMA)

MMA is a method that assesses the quality of feature matching between pairs of images. It does this by only considering feature matches that are mutual nearest neighbors. In MMA evaluation, the x-axis represents the matching threshold in pixels, while the y-axis shows the average accuracy of matching for image pairs. A correct match is one where the reprojected error of the homography estimate is below the specified matching threshold. MMA calculates the average percentage of correct matches for various pixel error thresholds and provides an overall score based on the average performance across all image pairs.

Homography estimation experiments

In the experiment of homography estimation, we conducted the AUC of angular errors at 3, 5, and 10 pixel thresholds.

Based on the SEN12MS dataset, we select four modal image data pairs (NIR-RGB,NIR-SWIR,SAR-NIR,SAR-SWIR) for the homography estimation experiments. As shown in Table 1, the experimental results of FmCFA in all four modalities achieve optimal results.

In addition, we conducted homography estimation tests on the Optical-SAR, RGB-NIR, WHU-OPT-SAR, and NYU-Depth V2 datasets. As shown in Table 2, under these datasets, FmCFA has significant improvements compared to other methods at 3, 5, and 10 pixel thresholds.

Mean matching accuracy experiment

Based on the SEN12MS dataset, we select four modal image data pairs (NIR-RGB,NIR-SWIR,SAR-NIR,SAR-SWIR) to perform the mean matching accuracy experiments. The experimental results are shown in Fig. 7. The horizontal coordinate (x-axis) of the image is the pixel threshold and the vertical coordinate (y-axis) is the ratio of correct matching. According to the figure, it can be seen that FmCFA, FeMIP and LoFTR are the most competitive methods. In most cases, FmCFA achieved better results.

Next, we conducted experiments on the average matching accuracy under several other modal datasets. These datasets include RGN-NIR Scene, NYU-Depth V2, Optical-SAR, and WHU-OPT-SAR. The results of the experiments are shown in Fig. 8. FmCFA, FeMIP, and LoFTR are the most competitive methods. FmCFA has a better matching accuracy in most cases at both low and high thresholds.

However, as shown in Figs. 7 and 8, FmCFA still exhibits some limitations when handling feature matching between near-infrared (NIR) images and optical RGB images. Specifically, when the pixel threshold is low, FmCFA does not achieve optimal results in NIR-RGB image feature matching. This is because the texture of infrared images is less pronounced, making it challenging for FmCFA to extract sufficient key features. In the future, we will focus on improving the extraction of key features from infrared images and aim to further enhance the performance of FmCFA.

Multimodal image matching visualization

We compare it with an excellent method, FeMIP24. We demonstrated matching performance in four modal image pairs (NIR-RGB, SAR-SWIR, SAR-NIR, and NIR-WIR) of SEN12MS, as shown in Fig. 9. Compared with FeMIP, FmCFA has more and more accurate matching connections, proving its better matching ability.

In addition, we also demonstrated visual matching performance under four other types of image data. These four types of data are: NYU Depth V2, Optical SAR, RGB NIR Scene, and WHU OPT-SAR. As shown in Fig. 10, FmCFA also has better matching performance.

Ablation experiment

We make several ablation comparisons in the way we select critical fatures. The selected benchmarks include: feature vector modulus, feature vector variance, average pooling and maximum pooling. As shown in Table 3, all of these approaches achieved good results, but average pooling is the best. We perform a homography estimation experiment on the Optical-SAR dataset to make a comparison.

Conclusion

This parper proposes a new feature matching method called FmCFA for multimodal image datasets. We propose a new attention interaction mechanism (CF-Attention) that concentrates interactions in critical areas and apply it to the CFa-Block. We have conducted a large number of experiments on various modal datasets. In these experiments, FmCFA achieved excellent matching results. This further proves the effectiveness and robustness of FmCFA.

Data availability

The datasets examined in this study can be accessed from the following publicly available resources: https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/1474000; https://cs.nyu.edu/ silberman/datasets/nyu_depth_v2.html; https://ivrlwww.epfl.ch/supplementary_material/cvpr11/index.html; https://github.com/AmberHen/WHU-OPT-SAR-dataset.

References

Feng, Y. et al. Occluded visible-infrared person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Multim. 25, 1401–1413. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2022.3229969 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. Visible-infrared person re-identification via cross-modality interaction transformer. IEEE Trans. Multim. 25, 7647–7659. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMM.2022.3224663 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. Homogeneous and heterogeneous relational graph for visible-infrared person re-identification. Pattern Recognit. 158, 110981. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PATCOG.2024.110981 (2025).

Jiang, L., Fan, H. & Li, J. A multi-focus image fusion method based on attention mechanism and supervised learning. Appl. Intell. 52(1), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10489-021-02358-7 (2022).

Puente-Castro, A., Rivero, D., Pazos, A. & Fernández-Blanco, E. UAV swarm path planning with reinforcement learning for field prospecting. Appl. Intell. 52(12), 14101–14118. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10489-022-03254-4 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Attention-guided progressive neural texture fusion for high dynamic range image restoration. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 2661–2672. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2022.3160070 (2022).

Liao, Y. et al. Feature matching and position matching between optical and SAR with local deep feature descriptor. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 15, 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3134676 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Shape-Former: Bridging CNN and transformer via ShapeConv for multimodal image matching. Inf. Fusion. 91, 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.INFFUS.2022.10.030 (2023).

Liu, G., Li, Z., Yang, J. & Zhang, D. Exploiting sublimated deep features for image retrieval. Pattern Recognit. 147, 110076. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PATCOG.2023.110076 (2024).

Ma, Y., Liu, Z. & Chen, P. C. L. Hybrid spatial-spectral feature in broad learning system for hyperspectral image classification. Appl. Intell. 52(3), 2801–2812. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10489-021-02320-7 (2022).

Hong, D. et al. More diverse means better: multimodal deep learning meets remote-sensing imagery classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 59(5), 4340–4354. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2020.3016820 (2021).

Feng, K. et al. Mosaic convolution-attention network for demosaicing multispectral filter array images. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging. 7, 864–878. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCI.2021.3102052 (2021).

Lowe, D. G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 60(2), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:VISI.0000029664.99615.94 (2004).

Fu, Z., Qin, Q., Luo, B., Wu, C. & Sun, H. A local feature descriptor based on combination of structure and texture information for multispectral image matching. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16(1), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2018.2867635 (2019).

Cheng, M. & Matsuoka, M. An enhanced image matching strategy using binary-stream feature descriptors. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 17(7), 1253–1257. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2019.2943237 (2020).

Ye, Y., Shen, L., Hao, M., Wang, J. & Xu, Z. Robust optical-to-SAR image matching based on shape properties. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 14(4), 564–568. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2017.2660067 (2017).

Xiong, X., Xu, Q., Jin, G., Zhang, H. & Gao, X. Rank-based local self-similarity descriptor for optical-to-SAR image matching. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 17(10), 1742–1746. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2019.2955153 (2020).

Gao, K., Aliakbarpour, H., Seetharaman, G. & Palaniappan, K. DCT-based local descriptor for robust matching and feature tracking in wide area motion imagery. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 18(8), 1441–1445. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2020.3000762 (2021).

Sarlin, P.E., DeTone, D., Malisiewicz, T. & Rabinovich, A. SuperGlue: Learning feature matching with graph neural networks. In 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 4937–4946 (2020).

Ma, T., Ma, J., Yu, K., Zhang, J. & Fu, W. Multispectral remote sensing image matching via image transfer by regularized conditional generative adversarial networks and local feature. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 18(2), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2020.2972361 (2021).

Jiang, B., Sun, P. & Luo, B. GLMNet: Graph learning-matching convolutional networks for feature matching. Pattern Recogn. 121, 108167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2021.108167 (2022).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A.N. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2017, December 4-9, 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA (eds. Guyon, I. et al.). 5998–6008. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/hash/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Abstract.html (2017).

Sun, J., Shen, Z., Wang, Y., Bao, H. & Zhou, X. LoFTR: Detector-free local feature matching with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 8922–8931 (2021).

Di, Y. et al. FeMIP: detector-free feature matching for multimodal images with policy gradient. Appl. Intell.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-023-04659-5 (2023).

Wang, Q., Zhang, J., Yang, K., Peng, K. & Stiefelhagen, R. MatchFormer: Interleaving attention in transformers for feature matching.

Truong, P., Danelljan, M., Gool, L.V. & Timofte, R. GOCor: Bringing Globally Optimized Correspondence Volumes into Your Neural Network. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, December 6–12 (eds. Larochelle, H. et al.) https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/a4a8a31750a23de2da88ef6a491dfd5c-Abstract.html (2020).

Truong, P., Danelljan, M., Gool, L.V. & Timofte, R. Learning Accurate Dense Correspondences and When To Trust Them. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2021, virtual, June 19-25, 2021 5714–5724. https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content/CVPR2021/html/Truong_Learning_Accurate_Dense_Correspondences_and_When_To_Trust_Them_CVPR_2021_paper.html (Computer Vision Foundation/IEEE, 2021).

Li, X., Han, K., Li, S. & Prisacariu, V. Dual-resolution correspondence networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, NeurIPS 2020, December 6-12 (eds. Larochelle, H. et al.). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2020/hash/c91591a8d461c2869b9f535ded3e213e-Abstract.html (2020).

Liu, Z., Hu, H., Lin, Y., Yao, Z., Xie, Z., Wei, Y. et al. Swin Transformer V2: Scaling Up Capacity and Resolution.

Chen, Z., Duan, Y., Wang, W., He, J., Lu, T., Dai, J. et al. Vision Transformer Adapter for Dense Predictions.

Zhang, H., Li, F., Liu, S., Zhang, L., Su, H., Zhu, J. et al. DINO: DETR with Improved DeNoising Anchor Boxes for End-to-End Object Detection.

Zong, Z., Song, G. & Liu, Y. DETRs with Collaborative Hybrid Assignments Training.

Bao, H., Dong, L., Piao, S. & Wei, F. BEiT: BERT Pre-Training of Image Transformers.

Tu, Z., Talebi, H., Zhang, H., Yang, F., Milanfar, P., Bovik, A. et al. MaxViT: Multi-Axis Vision Transformer.

Katharopoulos, A., Vyas, A., Pappas, N. & Fleuret, F. Transformers are RNNs: Fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning. vol. 119 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research (ed. Singh, A.) 5156–5165. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/katharopoulos20a.html (PMLR, 2020).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015—18th International Conference Munich, Germany, October 5–9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III. vol. 9351 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science (ed. Navab, N.) 234–241 (Springer, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28.

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. CoRR. (2015). arxiv:1512.03385.

Roßberg, T. & Schmitt, M. Estimating NDVI from Sentinel-1 Sar data using deep learning. In IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, IGARSS 2022, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, July 17–22, 2022 1412–1415. https://doi.org/10.1109/IGARSS46834.2022.9883707 (2022).

Liao, Y. et al. Feature matching and position matching between optical and SAR with local deep feature descriptor. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 15, 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3134676 (2022).

Zhang, G. et al. MCANet: A joint semantic segmentation framework of optical and SAR images for land use classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Observ. Geoinf. 106, 102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2021.102638 (2022).

Brown, M.A. & Süsstrunk, S. Multi-spectral SIFT for scene category recognition. In The 24th IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2011, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2011.5995637 (2011).

Silberman, N., Hoiem, D., Kohli, P. & Fergus, R. Indoor segmentation and support inference from RGBD images. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2012—12th European Conference on Computer Vision, Florence, Italy, October 7–13, 2012, Proceedings, Part V. vol. 7576 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science (eds. Fitzgibbon, A. W. et al.) 746–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33715-4_54 (2012).

Li, J., Xu, W., Shi, P., Zhang, Y. & Hu, Q. LNIFT: locally normalized image for rotation invariant multimodal feature matching. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2022.3165940 (2022).

Mishchuk, A., Mishkin, D., Radenovic, F. & Matas, J. Working hard to know your neighbor’s margins: Local descriptor learning loss. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 30 (ed. Guyon, I.) (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017). https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/831caa1b600f852b7844499430ecac17-Paper.pdf.

Vassileios Balntas DP Edgar Riba, Mikolajczyk K. Learning local feature descriptors with triplets and shallow convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC) (ed. Richard, C.) 119.1–119.11. https://doi.org/10.5244/C.30.119 (BMVA Press, 2016).

Liao, Y. et al. Feature matching and position matching between optical and SAR with local deep feature descriptor. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 15, 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2021.3134676 (2022).

Han, X., Leung, T., Jia, Y., Sukthankar, R. & Berg, A.C. MatchNet: Unifying feature and metric learning for patch-based matching. In 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 3279–3286 (2015).

Sarlin, P.E., DeTone, D., Malisiewicz, T. & Rabinovich, A. SuperGlue: Learning feature matching with graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Open Foundation of Yunnan Key Laboratory of Software Engineering under Grant No.2020SE307, and the Scientific Research Foundation of Education Department of Yunnan Province under Grant No.2021J0007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.: Hardware and methodology; X.W.: Software and writing; J.L.: Data preparation; P.L.: Experimentation; Z.P.: Formal analysis; Q.D.: Investigation;

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical and informed consent for data used

This submission does not include human or animal research.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, Y., Wu, X., Liu, J. et al. FmCFA: a feature matching method for critical feature attention in multimodal images. Sci Rep 15, 6640 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90955-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90955-8