Abstract

The genus Quercus with over 1,000 species, is extensively dispersed throughout the temperate woodlands of the Northern Hemisphere and tropical climate zones. The Quercus genus is rich in phenolic acids, triterpenoids, and plant-based polyphenolic compounds. It also has numerous biological effects, such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, liver-protective, gastroprotective, anticancer, antidiabetic, and antioxidant activities. To investigate the morphological and phytochemical diversity of Iranian oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) populations from ten different geographic regions in Iran were collected. Morphological, phytochemical and cytotoxic traits were measured and analyzed. Among morphological and phytochemical traits, dry leaf weight (69.21%) had the maximum coefficient of variation. In addition, the highest total phenol (100.17 mg GAE/g DW), total flavonoid content (74.6 mg RE/g DW), and total tannin (56.60 mg GAE/g DW) were found in the Sardasht population, with the minimum in the Piranshahr population. The IC50 values of the populations ranged from 5.52 to 18.65 µg/mL, with the lowest in the Sardasht population and the most elevated in the Ilam population. Gallic acid, salicylic acid, rutin, and rosmarinic acid were identified as the principal phenolic compounds. Cluster analysis of populations based on morphological and phytochemical data represented 3 main groups. Principal component analysis revealed that the first and second components explained 38.52% and 30.01% of the total variance, respectively. Oak fruit extracts were not cytotoxic at concentration of 100 µM. Based on the results of this study, the best oak population can be selected to achieve the highest yield, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and total tannin content, according to the needs of the pharmaceutical and food industries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For centuries, humans have relied on plants to meet vital needs such as nutrition and healthcare. Traditional medicine has utilized medicinal plants to manage and prevent a variety of health issues. Roughly 80% of people worldwide depend on traditional medicine as their main source of healthcare1,2. While the use of these herbs is expanding, concerns regarding their safety still persist3. Given the extensive history of herbal product usage, they are often regarded as safe or of low toxicity4. Nevertheless, contemporary research indicates that many herbal remedies used in traditional medicine may also lead to negative side effects5. Therefore, the research regarding the toxic effects of medicinal plant extracts that are consumed by humans and livestock is very important to determine their safety characteristics2.

Oaks (Quercus sp.) consists of evergreen or deciduous trees from the family Fagaceae, comprising approximately 450 species distributed throughout the Asian, European, North African, and North and Central American regions6. In many regions around the world, distinct segments of the oak tree have been employed as disinfectants and for the remediation of gastrointestinal disorders such as gastric ulcers, diarrhea, hemorrhoids, laryngopharyngitis diseases, menorrhagia, toothache, gastropathies, and as a healing agent in burns7,8,9,10. Various pharmacological impacts including antioxidant, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, dermatological disorders, anti-obesity, anti-cancer and neurological effects have been reported for the oaks (Quercus sp.). These outcomes are related to certain chemical substances, predominantly comprising triterpenoids, flavonoids, and tannins11,12,13,14,15,16. Quercus brantii Lindl. (Persian oak) is recognized as one of the principal tree species in this genus, found in the Zagros Mountains of Iran and encompassing over 50% of the nation’s western forests17. The fruit of the oak, known as acorn, is rich in minerals, vitamins, carbohydrates (45–85%), tannins, phenolic compounds, catechin, epicatechin, and gallocatechin18,19. In prior eras, acorn was regarded as a secondary food source, flour (to produce bread) or beverage (substitute for coffee after the roasting process) in the human diet. Nowadays, acorn fruit is extensively utilized as a highly nutritious source for the production of livestock and poultry feed as well as fodder20,21. The composition of acorn is greatly guided by climatic factors and the soil conditions21. The phytochemical diversity and plant growth traits are strongly influenced by temperature, precipitation, soil type, and other environmental factors22,23. Moreover, these components considerably affect the quantity and quality of pharmacologically relevant constituents (namely saponins, tannins, phenolic compounds and flavonoids)24. Preserving existing genetic diversity has become a global and international concern25. On the other hand, the raw materials required by the pharmaceutical industries and consumables for livestock and poultry feed are sourced from native environments. For this reason, to defend the natural habitats of oaks and accommodate basic needs, cultivation and revitalization of this plant in natural habitats and underutilized lands are deemed essential. However, having sufficient information regarding genetic diversity plays a vital role for breeders to choose the optimal populations with respect to performance, phytochemical properties, and with the least cytotoxicity, for use in cultivation and revitalization programs26. This investigation intended to investigate the morphological diversity and phytochemical compounds of the acorn in different populations of Persian oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) for the purpose of choosing the optimal population for breeding programs, cultivation, and revitalization of this plant, and to meet the needs of the medicinal manufacturing and agro-food sector.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

According to the research and investigation of Iran’s flora, the indigenous habitats of Iranian oak were identified. 10 populations were collected from 6 provinces of Iran. Each population included 10 individual, one tree was randomly selected as the central sample, and other samples were sampled from the same area at a distance of more than 100 m from each other. Leaf and fruit samples from different populations were collected to evaluate morphological traits. Fruits were used to investigate phytochemical traits. The collected samples were conveyed to the Ecophysiology Laboratory, Medicinal Plants and Drug Research Institute (MPH), Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran and dried in an oven at 40 °C. Herbarium samples were prepared from different populations and stored in the Herbarium of MPH and an herbarium code was assigned to each population. Climatic and geographical characteristics of the collection site of different Iranian oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) populations provided in Table 1; Fig. 1. The authors confirm that the necessary permissions to collect and cultivation the samples have been obtained and also the present study complies with the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Morphological traits

Eight traits related to leaf and fruit traits were evaluated. From each tree, 20 leaf samples and 10 fruit samples were measured and their average was considered. Morphological traits were measured visually and using a ruler27. The traits of fruit length and fruit width were determined using a digital measuring instrument. Performance characteristics such as fresh and dry weight of leaves, fresh and dry weight of fruits in each sample were also measured using a digital scale that has a precision of 0.01 g.

Phytochemical analysis

Extraction

500 mg of oak fruits were milled and then dispersed in 20 ml of 80% (v/v) methanol, followed by ultrasonic treatment (Elma, S120H, Germany) for 20 min at 40ºC. The acquired specimen was centrifuged in a cooled centrifuge (R5702; Eppendorf) at 3000 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatant was preserved in the refrigerator until subsequent analysis.

Total phenol content

To measure the overall phenol content, the Folin-Ciocalteu method was utilized. In this assay, 0.5 ml of the fruit extract were combined with 2.5 ml of the Folin reagent and left at room temperature for 5 min. Subsequently, 2 ml of a 75 g/l sodium carbonate solution was added. Once the samples had been incubated for 60 min, their absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a Shimadzu double beam UV-visible spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Japan). A calibration curve was plotted using the extinction values versus gallic acid concentrations, and the total phenolic content of the samples was expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry weight (mg GAE/g DW)28.

Total flavonoid content

The flavonoid content was determined by reacting the fruit extract with aluminum chloride. A mixture was prepared by adding 1.5 ml of methanol, 0.1 ml of a 10% ethanol solution of aluminum chloride, 0.1 ml of potassium acetate (1 M), and 2.8 ml of distilled water to 0.5 ml of the extract. The samples were then incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and their absorbance was recorded at 415 nm. A standard calibration curve was generated from various concentrations of rutin as the reference standard. The results of the flavonoid analysis were calculated and presented as mg of rutin equivalent per g of dry matter (mg RE/g DW)29.

Antioxidant activity

Radical-scavenging capacity of the samples using the DPPH method and spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Japan) were measured against standard antioxidant gallic acid30,31. 2.7 ml of the DPPH (6 × 10− 5 M) solution was mixed with 0.3 ml of the fruit extract at various concentrations (3.125, 6.25, 12.50, 25, 50, and 100 µg/ml). The solution was stirred continuously for 60 min in the absence of light. Subsequently, the absorbance of the solutions was measured at a wavelength of 517 nm using a spectrophotometer. The antioxidant activity, expressed as the free radical scavenging capacity (RSC) of DPPH, was determined by calculating the IC50 value based on the following formula:

DPPH scavenging effect (%) = (Abs0 – Abs1/Abs0) × 100.

Abs0 = Control absorbance.

Abs1 = Sample absorbance.

Total tannin content

A total of 100 mg of powdered fruit was combined with 5 ml of diethyl ether containing 1% acetic acid and stirred on a magnetic stirrer for 15 min. Following this, the mixture was centrifuged (centrifuge Rotanta 460r, Hettich, Germany) at 2000 rpm for a period of 10 min. The resulting supernatant was removed, and the remaining precipitate was re-suspended in a 5 ml solution of 70% acetone (v/v). The mixture was then gently agitated on a shaker at a speed of 90 rpm for one hour. This was followed by an additional centrifugation step at 2000 rpm for 20 min. The total phenolic content present in the acetone extract was then determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay method as described by Slinkard and Singleton28. A 25 µl aliquot of the extract was mixed with 125 µl of 10% (v/v) Folin reagent and 100 µl of 7.5% (w/v) sodium carbonate. Following 90 min of shaking at 40 rpm in the dark, the absorbance was read at 765 nm. Additionally, 2 ml of the acetone extract was diluted with 100 ml of polyethylene glycol to precipitate tannins and stored at 4°C for 15 min. After centrifuging at 3000 rpm, the absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 725 nm. The total tannin content was calculated by subtracting the phenolic content before and after polyethylene glycol treatment32.

Assay of phenolic compounds using HPLC

Phenolic compounds were determined using a high-performance liquid chromatography (Knauer, Germany) photodiode array, with a Waters 2695 separations module equipped with a C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm) and a UV detector (Waters 2487). The mobile phase consisted of methanol (solvent A) and distilled water (solvent B). HPLC solvents both contained TFA (0.02%, v/v), and the flow rate was 0.5 ml/min. The gradient program was begun with 20%A: 80%B followed by 20:80–30:70 over 10 min, 30:70–50:50 over 10 min, 50:50 for 20 min, 50:50–100:0 over 2 min, 100:0 for 6 min, 100:0–20:80 over 7 min. The analysis was conducted under optimized conditions, with a 20 µl injection volume and a column temperature of 25 °C, to ensure accurate and reliable results. To detect phenolic compounds, the UV absorption peaks at 200–600 nm were investigated. Standard samples were used as references to identify compounds based on their characteristic retention times under equivalent analytical conditions. Pure standards of phenolic compounds were prepared from Sigma Aldric Co. (Buchs, Switzerland). Calibration curves were constructed by injecting standard mixture solutions at the seven concentrations of 2, 10, 50, 100, 250, 500, and 1000 ppm (Table 2). The results were presented in mg/g DW.

Cytotoxicity assay

Normal cell lines (HDF) and gastric cancer cells (MKN45) were obtained from Iran National Cell Bank (Pasteur Institute, Iran). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium sourced from Gibco, supplemented with 10% Gibco fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (streptomycin at 100 µg/ml and penicillin at 100 units/ml). These cells underwent incubation at 37 °C within a humid atmosphere enriched with 5% CO2 to facilitate growth. After reaching 80% concentration, the cells were cultured using X1 trypsin/EDTA (Gibco) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solutions.

Cell viability assay (MTT)

The survival of cultured cells after treatment was measured using the MTT method. Briefly, the cells were first separated from the cell culture flask with trypsin/EDTA solution. Then the cells were harvested, resuspended in the medium and planted in a 96-well plate. The final volume of medium and seed cells were 200 µl per well and 1.4 × 104 cells per well, respectively. After 24 h incubation, when the plated cells were formed as a monolayer, the plate wells were treated with 6.25–100 µg/ml extract in three replicates for 48 h. Following incubation, with the intact cell monolayer still in place, the culture medium was extracted. Each well then received 200 µl of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml in phosphate buffered saline, and the plate was further incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the MTT mix was removed, and 100 µl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was introduced. The plate was then agitated at 37 °C until full dissolution of the formed crystals occurred. The impact of the extract on cell viability was assessed by reading the absorbance at 570 nm using an ELISA plate reader (xs2 wave, BioTek, USA). The IC50 value, corresponding to the extract concentration that reduces cell growth by 50%, was derived from the dose-response curve generated from the data.

Statistical analysis

The studies were executed using a Completely Randomized Design (CRD), incorporating five repeats for each treatment. Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS software (version 9.2), and the means were compared using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test to identify significant differences. Diagram of correlation coefficients (Pearson correlation), cluster analysis (Ward’s method) and factor analysis (Varimax rotation procedure) for morphological and phytochemical traits were performed using software R version 4.3.2. All graphs were drawn by software R version 4.3.2.

Results and discussion

Morphological traits

Significant diversity was observed among Iranian oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) populations in terms of morphological traits, allowing for selection of these traits across different populations (Table 3). The findings from the mean comparison across the investigated groups indicated that the highest fresh leaf weight was in the YAS population (1.17 g), and the lowest was in the BAN population (0.24 g). The comparison of dry leaf weight indicated that the YAS population had the highest average dry leaf weight (0.76 g), while the BAN population had the lowest (0.10 g). The mean comparison of fresh fruit weight showed that the BAN population had the highest average (13.45 g), and the TEH population had the lowest (2.29 g). In terms of dry fruit weight, the TEH population had the lowest average (1.28 g), while the BAN population had the highest (9.20 g). Leaf length varied between 5.32 and 10.3 cm, and leaf width varied between 2.19 and 6.75 cm. The YAS population had the longest fruit length (4.85 cm), while the TEH population had the shortest (1.83 cm). The largest fruit diameter was found in the BAN population (2.44 cm), and the smallest in the TEH population (0.65 cm) (Table 4; Fig. 2). Earlier research has consistently shown the extensive variation in morphological traits among Quercus sp. populations33,34,35,36. Khadivi et al.36 noted that the wild edible fruits of these plants exhibit significant genetic diversity. This indicates that wild species may play a crucial role in the genetic diversity of crops37. Furthermore, the natural process of repeated dispersal of wild fruit seeds promotes their genetic variability.

Phytochemical traits

Total phenolic and total flavonoid content

The total phenolic and flavonoid concentrations were determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent method and the aluminum chloride method, respectively. Notable variations in the total phenolic and flavonoid levels of the fruit extract were detected among different oak populations (P < 0.01). The SAR population exhibited the highest total phenolic content at 17.100 mg GAE/g DW, while the ILA, PIR and SAQ populations had the lowest, with values of 46.92 mg GAE/g DW, 50.2 mg GAE/g DW and 51.15 mg GAE/g DW respectively, with no significant difference between them (Fig. 3). According to a study by Maslova et al.37, the highest known concentration of total phenolic compounds in acorns was found in Quercus suber, with a remarkable value of 233,350 mg per 100 g of dry weight. In contrast, Tejerina et al.38 observed a comparatively lower content of total phenolic compounds, ranging from 840 to 9163 mg/100 g DW, in the acorns of Quercus rotundifolia. This variation was attributed to the timing of seed harvest throughout the year and over two consecutive years, suggesting that the composition of acorns varies with their maturity level and indicating an ongoing maturation process both during tree growth and post-harvest38,39.

Polyphenolic compounds exhibit robust antioxidant activity attributed to their proficiency in capturing free radicals. and form complexes with metal ions, a property attributed to their chemical structure. Various methods exist for producing polyphenolic constituents in plants, and their arrangement within plant tissues is governed by multiple mechanisms. Several factors, including genetic factors, environmental and climatic conditions, as well as the choice of extraction solvent, significantly influence the concentration of phenolic and flavonoid compounds in plants40. Flavonoids form the largest category of naturally occurring phenolic substances found throughout different parts of plants and possess numerous biological activities41. The SAR population exhibited the highest average of 74.06 mg RE/g DW in total flavonoid content, while the ILA and PIR populations had the lowest (30.48 and 28.78 mg RE g DW, respectively) (Fig. 3). Taib et al.42 indicated that Q. faginea had a total flavonoid content of 6.2 mg/g of dry extract, while Q. rotundifolia had 10.3 mg/g. Seasonal fluctuations and the various stages of maturity have consistently been identified as influential factors in the variability of phenolic and flavonoid compounds within Quercus species43,44,45. However, the majority of research on Quercus brantii extracts has primarily focused on comparing the compositional differences of these compounds among different plant parts or in relation to other Quercus taxa.

Polyphenolic compounds and flavonoids possess a chemical structure that enables them to neutralize free radicals, resulting in significant antioxidant properties. The fruits obtained from the investigated Iranian oak populations displayed a diverse array of phenolic and flavonoid compounds. Plants synthesize these polyphenolic compounds through a variety of mechanisms. Furthermore, the distribution of these compounds across different plant tissues varies46. The extraction of phenolic and flavonoid compounds from plants is significantly impacted by various factors, with environmental and climatic conditions being among the most influential determinants of their concentrations47.

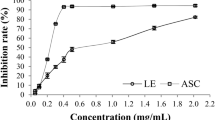

Antioxidant activity

The assessment of antioxidant capacity through the DPPH radical method is a widely recognized assay for measuring the antioxidant potential of different compounds. This technique relies on the ability of antioxidants to reduce the DPPH free radical in an environment devoid of other free radicals. A significant variation in antioxidant activity was observed among the different oak populations (Fig. 4). According to the results, the percentage of DPPH free radical inhibition ranged from 5.52 to 18.65% across the populations. The ILA, SAQ, and PIR populations (with the highest IC50 values) exhibited the lowest antioxidant activity, whereas the GAC, SAR, and MAR populations, with the lowest IC50 values, demonstrated the strongest antioxidant activity. Variability in acorn extract properties likely reflects differences in nutritional and phytochemical profiles. High phenolic content is consistently linked to enhanced antioxidant capacity in acorn extracts21,48. Numerous studies have found a consistent positive association between the antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of fruits and vegetables, indicating that the phenolic compounds present in these foods are key contributors to their overall antioxidant potential19,42,49. Antioxidants are incorporated into food products to mitigate degradation resulting from the oxidation of unsaturated fats. There has been a growing preference for natural antioxidants over synthetic alternatives due to their reduced side effects. As a result, there has been an increased emphasis on the discovery of natural antioxidants compared to previous years. In contrast, synthetic antioxidants have been associated with adverse effects on the blood coagulation, thyroid, liver, lungs, as well as exhibiting carcinogenic properties. Phenolic compounds are the primary constituents of natural antioxidants, and these compounds are prevalent in numerous medicinal plants47. Research has consistently shown that extracts rich in phenolic compounds exhibit significantly enhanced antioxidant properties compared to those with lower phenolic content, underscoring the key role of these compounds in mediating antioxidant activity50.

Tannin content

The tannin content in various populations was measured using methanolic extracts based on the Folin-Ciocalteu method. Based on the findings, the maximum total tannin content was recorded in the SAR (56.60 mg GAE/g DW), MAR (48.29 mg GAE/g DW), and GAC (47.05 mg GAE/g DW) populations, while the lowest total tannin content was found in the ILA (26.87 mg GAE/g DW), PIR (27.25 mg GAE/g DW) and SAQ (27.95 mg GAE/g DW) populations (Fig. 5). Phenolic compounds are among the most complex plant compounds, recognized as protective agents against free radicals. The category of phenolic compounds consists of simple phenols, phenolic acids, quinones, tannins, coumarins, and flavonoids. Tannins are a general term for a large group of polymeric phenols, with molecular weights ranging from 500 to 300051. In a study by Rakić, et al.52, the total tannin content in the acorns of Quercus robur was found to be 20,400 mg per 100 g DW. Tejerina, et al.38 reported that the acorns of Quercus rotundifolia contained 950–1150 mg of hydrolyzable tannins per 100 g DW, along with 50–140 mg of condensed tannins per 100 g DW. Among the hydrolyzable tannins, gallotannins were measured at levels reaching 860 mg/100 g DW, while ellagitannins were found at up to 290 mg/100 g DW. Hydrolyzable tannins are primarily found in sources such as oak, grape seeds, and pomegranate peels, which are not easily incorporated into a regular diet53. As a result, there is a need for a plant rich in Hydrolyzable tannins, along with efficient extraction methods to meet growing demand. Research has revealed that oak species contain a significant proportion of Hydrolyzable tannins in their tissues54,55. The high tannin content, ample reserves, and easy availability of oak raw materials have made oaks a focus of interest.

Phenolic compounds

To investigate the phenolic acid content of different oak populations, 14 standard (gallic acid, 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, salicylic acid, p-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, benzoic acid, syringic acid, ferulic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, and rutin) phenolic compounds were analyzed using HPLC. A total of four principle phenolic compounds were identified: gallic acid, salicylic acid, rosmarinic acid, and rutin (Figs. 6 and 7). The content of gallic acid ranged from 1.10 to 5.22 mg/g dry weight across the various oak populations, with the DAS population exhibiting the highest concentration and the TEH population showing the lowest (Table 5). The concentrations of ellagic and gallic acids in acorns are closely associated with the tannin content, as these acids are released through processes including temperature exposure, enzymatic activity, and the influence of acids and alkalis, among other factors39.

The highest salicylic acid (SA) concentration was noted in the BAN population (0.87 mg/g DW), while negligible amounts were detected in the ILA, TEH, DAS, GAC, and PIR populations. Skwarek-Fadecka’s findings indicate that reactive oxygen species (ROS) can stimulate the production and accumulation of SA, a phytohormone that participates in the process of developing systemic acquired resistance in plants56. SA plays a pivotal role in the signaling pathways activated in response to the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns in plants, serving as a critical mediator of plant defense response. These hormones are involved in various signaling pathways57,58,59. Rosmarinic acid (RA) was only detected in the PIR population (0.54 mg/g DW). RA and coumarins had previously only been detected in Quercus glabrescens, which suggests their potential as species-specific markers60. This study represents the first report of RA presence in Iranian oak. The rutin content varied from 0.34 to 2.71 mg/g DW, with the lowest concentration found in the SAQ population and the highest in the GAC population. Rutin is recognized for its P-vitamin activity, its ability to enhance blood vessel elasticity, and its notable antioxidant, antitumor, and radioprotective properties61. The phenolic profiles vary greatly among species. In a study conducted on the leaves of five different Quercus species (Q. acuta, Q. glauca, Q. myrsinifolia, Q. phylliraeoides, and Q. salicina), authors reported high levels of gentisic and chlorogenic acids, as well as of the flavonoids naringin and rutin in Q. salicina; but none of these compounds was detected in any other Quercus species62. On the other hand, Brossa et al.63 reported flavanols as the major constituents in holm oak (Q. ilex) leaves. Likewise, Cantos et al.64 reported different gallic acid derivatives in Q. ilex, Q. rotundifolia, and Q. suber.

Correlation and multivariate analyses

The fresh leaf weight shows a significant and positive correlation at the 5% level with dry leaf weight and leaf width. However, it does not show a significant correlation with fresh fruit weight, dry fruit weight, leaf length, fruit length, fruit diameter, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, total tannin content, or antioxidant activity (IC50). Antioxidant activity is positively and significantly correlated at the 5% level with total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and total tannin content. Fresh fruit weight is positively and significantly correlated at the 5% level with dry fruit weight, fruit length, and fruit diameter, but it does not show a significant correlation with other traits (Fig. 8). The overall yield of phytochemicals from a plant is determined by the effectiveness of its specialized organs, which are specifically adapted for the synthesis and accumulation of these valuable compounds, and because the metabolites of the Iranian oak are primarily formed in its fruit, any factor that increases fruit yield in this plant can effectively enhance metabolite production. Therefore, traits that influence the increase in fruit weight should be considered by breeders61.

Cluster analysis, a key technique for categorizing various populations based on their morphological and phytochemical characteristics, was performed (Fig. 9). The findings indicated that the populations were classified into three primary groups. Group A included four populations, BAN, YAS, DAS, and THE which were superior in traits such as fresh and dry fruit weight, fresh and dry leaf weight, and fruit length and diameter compared to the other populations. Groups B and C each contained three populations. Populations MAR, GAC, and SAR were placed in Group B, and populations PIR, ILA, and SAQ were in Group C. Populations in Group B were superior in phytochemical traits, including total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, tannin content, and antioxidant activity, whereas populations in Group C had the lowest levels of phytochemical compounds. The impact of environmental and geographical factors on gene expression levels, as well as the diversity of morphological traits and phytochemical compounds among plant populations, is well-recognized. Diversity within plants of the same plant species is affected by environmental factors and gene structure, as demonstrated by cluster analysis, where similar populations are positioned close to each other47.

The biplot generated using the first (PC1) and second (PC2) principal components demonstrated the diversity among the populations and divided them into two main groups (Fig. 10). The first and second components accounted for 38.52% and 30.01% of the total variance among the populations, respectively. The biplot derived from morphological and phytochemical traits corroborated the findings from the cluster analysis. In the study by Eghlima et al.65, PCA was used to evaluate different ecotypes of Equisetum arvense, where the morphological traits under study were categorized into three principal components, collectively accounted for 96.77% of the total variance. In another study on Rosa canina, morphological and phytochemical traits were classified into seven principal components using PCA, accounting for 93.53% of the total variance41.

Cytotoxicity assay

The diverse traditional uses and abundant phytochemical composition of the Quercus genus make these plants noteworthy for biological and toxicological studies. The MTT assay were performed to evaluate the inhibitory effect of acorn extracts from different oak populations on the viability of normal cell line (HDF) and gastric cancer cells (MKN45). The survival rate of HDF cells varied between 79.06 and 90.75% under the influence of various extracts. In addition, the survival rate of MKN45 cells was between 74.69 and 88.57% (Fig. 11). All the extracts demonstrated minimal cytotoxicity against the normal cell line. This suggests that these extracts may be relatively safe for non-cancerous cells. Oak various parts and products especially its fruits are used traditionally in Iranian herbal medicine to alleviate inflammation and pain and other ailments of gastro intestinal tract. MKN45 cell line is an established cell line for gastric cancer. Previous studies especially on oak fruit (acorn) extracts reported that it has moderate anti proliferative effect on AGS (a gastric cancer cell line). Therefore, in this study we tried to examine the anti-proliferative effect of extracts obtained from acorns on MKN45 gastric cancer cell line. However, our findings did not show significant cytotoxicity toward MKN45 cells66,67. Certain plant antioxidants are believed to play a role in their anti-cancer properties, and it has been reported that their flavanols can inhibit the growth of cancer cells in laboratory settings67,68.

Conclusion

Growing demand from pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries is driving innovation in the breeding of medicinal and spice plants. To identify and develop such genotypes in Iranian oak, the morphological and phytochemical diversity of its wild populations in Iran was investigated. Considerable variations in morphological traits, TPC, TFC, antioxidant activity and phenolic compound were observed among the studied oak populations that help the breeder to select the desired genotype. Gallic acid and rutin were the most abundant phenolic compounds in Iranian oak fruit extract. Also, the TPC and TFC in the fruit of the Iranian oak populations were significantly contributed to their antioxidant capacity. Based on the results of this study, the SAR, SAR, MAR, GAC and BAN populations were identified as superior populations in terms of phytochemical and functional traits, which can be used in future breeding programs according to the needs of the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 4, 177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2013.00177.20 (2014).

Ugwah-Oguejiofor, C. J. et al. Acute and sub-acute toxicity of aqueous extract of aerial parts of Caralluma dalzielii NE Brown in mice and rats. Heliyon 5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01179 (2019).

Ifeoma, O. & Oluwakanyinsola, S. Screening of herbal medicines for potential toxicities. New. Insights into Toxic. drug Test. 244, 63–88. https://doi.org/10.5772/54493.22 (2013).

Ibrahim, J., Muazzam, I., Jegede, I. & Kunle, O. Medicinal plants and animals sold by the Yan-Shimfidas of Sabo Wuse in Niger State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 4, 386–39471 (2010).

Koduru, S., Grierson, D. & Afolayan, A. The Foliar micro-morphology of Solanum aculeastrum. Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 9, 1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjbs.2006.1056.1060.48 (2006).

Burlacu, E., Nisca, A. & Tanase, C. A comprehensive review of phytochemistry and biological activities of Quercus species. Forests 11, 904. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11090904.23 (2020).

Joshi, A. K. & Juyal, D. Traditional and ethnobotanical uses of Quercus leucotrichophora a. Camus (Quercus Oblongata D. Don) in Kumaun and Garhwal regions of Uttarakhand, India: a review. Int. J. Herb. Med. 5, 06–0824 (2017).

Kim, Y-H. & Kim, J-W. Distributional uniqueness of deciduous oaks (Quercus L.) in the Korean Peninsula. J. Korean Soc. Environ. Rest. Tech. 20, 37–59. https://doi.org/10.13087/kosert.2017.20.2.37.27 (2017).

Moon, H. R. et al. Antiasthma effects through anti-inflammatory action of acorn (Quercus acutissima Carr.) In vitro and in vivo. J. Food Biochem. 37, 108–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-4514.2012.00652.x.25 (2013).

Khennouf, S., Amira, S., Arrar, L. & Baghiani, A. Effect of some phenolic compounds and quercus tannins on lipid peroxidation. World Appl. Sci. J. 8, 1144–114926 (2010).

Gezici, S. & Sekeroglu, N. Neuroprotective potential and phytochemical composition of acorn fruits. Ind. Crop Prod. 128, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.10.082.31 (2019).

Rocha-Guzmán, N. E. et al. Antioxidant activity and genotoxic effect on HeLa cells of phenolic compounds from infusions of Quercus resinosa leaves. Food Chem. 115, 1320–1325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.01.050.28 (2009).

Sati, S. C., Tripathi, A. N. & Kumar, P. Influence of different solvents on antibacterial potential of three species of Himalayan Oaks. Int J. Pharma Sci Res. 13 (1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.13 (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Seed germination schedule and environmental context shaped the population genetic structure of subtropical evergreen oaks on the Yun-Gui Plateau, Southwest China. Heredity 124, 499–513. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-019-0283-2.30 (2020).

Liu, C., Li, Y., Xu, L., Chen, Z. & He, N. Variation in leaf morphological, stomatal, and anatomical traits and their relationships in temperate and subtropical forests. Sci. Rep. 9, 5803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42335-2.32 (2019).

Sánchez-Moreno, C. Methods used to evaluate the free radical scavenging activity in foods and biological systems. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 8, 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1106/108201302026770.33 (2002).

Heydari, M., Pourbabaei, H., Rostami, T., Faghir mB, Salehi, A. & Ostad, R. Plant species in Oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) Understory and their relationship with physical and chemical properties of soil in different altitude classes in the Arghvan valley protected area, Iran. Casp. J. Env Sci. 11, 97–11034 (2013).

Karimi, A. & Moradi, M-T. Total phenolic compounds and in vitro antioxidant potential of crude methanol extract and the correspond fractions of Quercus brantii L. Acorn. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 4, 35–3935 (2015).

Popović, B. M., Štajner, D., Ždero, R., Orlović, S. & Galić, Z. Antioxidant characterization of oak extracts combining spectrophotometric assays and chemometrics. Sci. World J. 2013, 134656. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/134656 (2013).

Lopes, I. M. & Bernardo-Gil, M. G. Characterisation of Acorn oils extracted by hexane and by supercritical carbon dioxide. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 107, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/EJLT.200401039.36 (2005).

Vinha, A. F., Barreira, J. C., Costa, A. S. & Oliveira, M. B. P. A new age for Quercus spp. fruits: review on nutritional and phytochemical composition and related biological activities of acorns. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 15, 947–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/1541-4337.12220 (2016).

Chelghoum, M. et al. Influence of altitude, precipitation, and temperature factors on the phytoconstituents, antioxidant, and α-amylase inhibitory activities of Pistacia atlantica. J. Food Meas. Charact. 15, 4411–4425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-021-01006-5.38 (2021).

Suyal, R., Bahukhandi, A., Bhatt, I. D. & Rawal, R. S. Comparative analysis of biochemical attributes of genus polygonatum in Western Himalaya. Nat. Acad. Sci. Lett. 44, 457–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40009-020-01028-5.39 (2021).

Rawat, S., Bhatt, I. D. & Rawal, R. S. Variation in essential oil composition in rhizomes of natural populations of Hedychium Spicatum in different environmental condition and habitats. J. Essent. Oil Res. 32, 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/10412905.2020.1750497.40 (2020).

Duan, C. et al. Chitosan as a preservative for fruits and vegetables: a review on chemistry and antimicrobial properties. J. Bioresour Bioprod. 4, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.21967/jbb.v4i1.189.41 (2019).

Deperi, S. I. et al. Discriminant analysis of principal components and pedigree assessment of genetic diversity and population structure in a tetraploid potato panel using SNPs. PloS One. 13, e0194398. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194398.42 (2018).

Bruschi, P., Grossoni, P. & Bussotti, F. Within-and among-tree variation in leaf morphology of Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. Natural populations. Trees 17, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-002-0218-y.43 (2003).

Slinkard, K. & Singleton, V. L. Total phenol analysis: automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 28, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.5344/ajev.1977.28.1.49.44 (1977).

Arvouet-Grand, A., Vennat, B., Pourrat, A. & Legret, P. Standardization of propolis extract and identification of principal constituents. J. Pharm. Belg. 49, 462–46845 (1994).

Liyana-Pathirana, C. M. & Shahidi, F. Antioxidant activity of commercial soft and hard wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) as affected by gastric pH conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 2433–2440. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf049320i.46 (2005).

Babashpour-Asl, M. & Piryaei, M. Free radical scavengering and phenolic compounds of peel and pulp of quince. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 8, 91–101. https://doi.org/10.22059/ijhst.2020.285851.308.72 (2021).

Abdouli, H., Hadj-Ayed, M., Elham, M., Nabila, B. & Remedios Alvir Morencos, M. Proximate composition, and total phenols, tannins, flavonoids and saponins, and in vitro ruminal fermentation activity of fenugreek cut at three maturity stages. Livest Res. Rural Dev (2012). 24.47.

Abassi, M., Zouaoui, R., Mguis, K., Youssef, A. & Bejaoui, Z. Morpho-physiological and anatomical responses of cork oak (Quercus suber L.) seedlings under shade and drought stress 51 (2019).

Laoué, J. et al. Leaf morpho-anatomical adjustments in a Quercus pubescens forest after 10 years of partial rain exclusion in the field. Tree Physiol. 44, tpae047. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpae047 (2024).

Ramos, A., Leticia, M. & Bandala, V. M. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Ectomycorrhizas of Phylloporus (Boletales) and Quercus sapotifolia from Tropical Oak Forest of Eastern Mexico. Symbiosis 91, 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-023-00943-7.50 (2023).

Khadivi, A., Mirheidari, F. & Moradi, Y. Morphological variation of Persian oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) in Kohgiluyeh-va-Boyerahmad province, Iran. Trees 1–16 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-024-02528-3.52

Maslova, N. P. et al. Variations in morphological and epidermal features of shade and sun leaves of two species: Quercus Bambusifolia and Q. myrsinifolia. AM. J. BOT. 108, 1441–1463. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajb2.1706.53 (2021).

Tejerina, D., García-Torres, S., de Vaca, M. C., Vázquez, F. & Cava, R. Acorns (Quercus Rotundifolia Lam.) And grass as natural sources of antioxidants and fatty acids in the montanera feeding of Iberian pig: Intra-and inter-annual variations. Food Chem. 124, 997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.07.058.9 (2011).

Szabłowska, E. & Tańska, M. Acorns as a Source of Valuable Compounds for Food and Medical Applications: a review of Quercus species Diversity and Laboratory studies. Appl. Sci. 14, 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14072799.10 (2024).

Nađpal, J. D. et al. Phytochemical composition and in vitro functional properties of three wild rose hips and their traditional preserves. Food Chem. 241, 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.111.6 (2018).

Bakhtiar, Z., Eghlima, G., Hatami, M. & Mirjalili, M. H. Quantification of fatty acids in seed oil and important bioactive compounds in Iranian Rosa canina L. ecotypes for potential cosmetic and medicinal uses. Sci. Rep. 13, 22721. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50135-y.2 (2023).

Taib, M., Damiri, F., Rezzak, Y., Berrada, M. & Bouyazza, L. Chemical Composition, Nutritional, and antioxidant activity of two Quercus species acorns growing in Morocco. Lett. Appl. Nanobiosci. 13, 15 (2023).

Aung, T., Bibat, M. A. D., Zhao, C-C. & Eun, J-B. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities of Quercus Salicina Blume extract. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 29, 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10068-020-00755-1.19 (2020).

Brossa, R., Casals, I., Pintó-Marijuan, M. & Fleck, I. Leaf flavonoid content in Quercus ilex L. resprouts and its seasonal variation. Trees 23, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-008-0289-5.17 (2009).

Makkar, H. P. S., Dawra, R. K. & Singh, B. Tannin levels in leaves of some oak species at different stages of maturity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 54, 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2740540403.18 (1991).

Gharibi, S., Tabatabaei, B. E. S. & Saeidi, G. Comparison of essential oil composition, flavonoid content and antioxidant activity in eight Achillea species. J. Essent. Oil-Bear Plants. 18, 1382–1394. https://doi.org/10.1080/0972060X.2014.981600.5 (2015).

Pourhosseini, S. H. et al. Diversity of phytochemical components and biological activities in Zataria multiflora Boiss.(Lamiaceae) populations. S Afr. J. Bot. 135, 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2020.08.024.7 (2020).

Rtibi, K. et al. Phytochemical properties and pharmacological effects of Quercus ilex L. aqueous extract on gastrointestinal physiological parameters in vitro and in vivo. Biomed. Pharmacother. 94, 787–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.008 (2017).

Şöhretoğlu, D. & Renda, G. The polyphenolic profile of Oak (Quercus) species: a phytochemical and pharmacological overview. Phytochem Rev. 19, 1379–1426 (2020).

Roby, M. H. H., Sarhan, M. A., Selim, K. A. H. & Khalel, K. I. Evaluation of antioxidant activity, total phenols and phenolic compounds in thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.), sage (Salvia officinalis L.), and marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) extracts. Ind. Crop Prod. 43, 827–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.08.029.4 (2013).

Döner, D. & Icier, F. Exergoeconomic analysis of ultrasound-assisted extraction of tannins from acorn fruit. J. Food Eng. 367, 111851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2023.111851.3 (2024).

Rakić, S. et al. Influence of thermal treatment on phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties of oak acorns from Serbia. Food Chem. 104, 830–834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.025.8 (2007).

Fischer, U., Dettmann, J., Carle, R. & Kammerer, D. Impact of processing and storage on the phenolic profiles and contents of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 233, 797–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00217-011-1560-3.58 (2011).

Wang, Y. et al. Genome-wide identification of TCP transcription factors and their potential roles in hydrolyzable tannin production in Quercus variabilis Cupule. Front. Plant. Sci. 15, 1444081. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1444081 (2024).

Yin, P. et al. Bioactive components and antioxidant activities of oak cup crude extract and its four partially purified fractions by HPD-100 macroporous resin chromatography. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.09.018.57 (2019).

Skwarek-Fadecka, M., Nawrocka, J., Sieczyńska, K., Patykowski, J. & Posmyk, M. M. Effect of Oak Powdery Mildew on ascorbate–glutathione cycle and other antioxidants in Plant—Erysiphe alphitoides Interaction. Cells 13, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13121035 (2024).

Kaur, S. et al. How do plants defend themselves against pathogens-biochemical mechanisms and genetic interventions. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants , 485–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12298-022-01146-y (2022).

Turczański, K. et al. Resistance inducers for the protection of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur L.) seedlings against powdery mildew Erysiphe alphitoides. Plants 12 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030635.63 (2023).

Zeng, Y., Song, H., Xia, L., Yang, L. & Zhang, S. The responses of poplars to fungal pathogens: a review of the defensive pathway. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 1107583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1107583.60 (2023).

Castillo-Mendoza, E., Zamilpa, A., González-Cortazar, M., Ble-González, E. A. & Tovar-Sánchez, E. Chemical constituents and their production in Mexican Oaks (Q. Rugosa, Q. Glabrescens and Q. Obtusata). Plants 11 (2610). https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11192610 (2022).

Konovalova, O. et al. Investigation of the polyphenol composition of red oak (Quercus rubra L.) raw materials. ScienceRise Pharm. sci. 75–81. https://doi.org/10.15587/2519-4852.2023.277969.65 (2023).

Kim, J. J. et al. Comparison of phenolic compounds content in indeciduous Quercus species. J. Med. Plant. Res. 6, 5228–5239 (2012).

Brossa, R., Casals, I., Pintó-Marijuan, M. & Fleck, I. Leaf flavonoid content in Quercus ilex L. resprouts and its seasonal variation. Trees 23, 401–408 (2009).

Cantos, E. et al. Phenolic compounds and fatty acids from acorns (Quercus spp.), the main dietary constituent of free-ranged Iberian pigs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 6248–6255 (2003).

Eghlima, G., Esmaeili, H., Frzaneh, M. & Mirjalili, M. H. Multivariate analysis of Equisetum arvense L. ecotypes based on silicon content, phytochemical and morphological characterization. Silicon 16, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-023-02660-8.1 (2024).

Bidaki, A. Z. et al. Examining the effect of extract of oak fruit jaft on AGS Cell lines. Iran. J. Ped Hematol. Oncol. 13 (3), 166–171 (2023).

Moradi, M., Karimi, A. & Alidadi, S. In vitro antiproliferative and apoptosis-inducing activities of crude ethyle alcohole extract of Quercus brantii L. Acorn and subsequent fractions. Chin. J. Natu Med. 14, 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1875-5364(16)30016-4 (2016).

Scalbert, A., Johnson, I. T. & Saltmarsh, M. Polyphenols: antioxidants and beyond. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 215s–217s. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/81.1.215S.66 (2005).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Research Council of Shahid Beheshti University for their financial support.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Farzaneh Shakuri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft. Ghasem Eghlima: Supervision, Investigation, Editing-original draft, Data curation, Data analysis. Hossein Behboudi: Methodology and Validation Writing-review. Marzieh Babashpour-Asl: Editing and Writing-review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shakuri, F., Eghlima, G., Behboudi, H. et al. Phytochemical variation, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of wild populations of Iranian oak. Sci Rep 15, 6534 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90991-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90991-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Variability in lutein and zeaxanthin content, fatty acid and phytosterols profiles, and genetic parameters of some Tagetes spp. cultivars

BMC Plant Biology (2026)

-

Agro-morphological and phytochemical diversity among Alcea Kurdica populations using multivariate analyses

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Evaluation of performance, essential oil composition, and genetic parameters of Grammosciadium platycarpum populations toward developing high-linalool industrial cultivars

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Variability in seed oil content, fatty acids profile, phytochemical properties, mineral and proximate composition of Iranian cultivars of vitis vinifera L

Scientific Reports (2025)