Abstract

Low blood glucose levels and high urea nitrogen levels affect patient prognosis, but few studies have investigated whether the blood urea nitrogen to glucose (BGR) ratio predicts the risk of death.This retrospective research examined the connection between the BGR and 365-day mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 1–4 admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). The study utilized data from 6,380 patients in the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV version 2.2 (MIMIC-IV v2.2), taking into account confounding factors such as demographics, vital signs, laboratory indicators, and comorbidities. The study employed both univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses stratified by BGR quartiles. Additionally, restricted cubic spline regression and inflection point analysis were used to explore the linear relationship between BGR and 365-day mortality, while Kaplan-Meier curve analysis was used to observe mortality changes under different BGR stratifications. Subgroup and mediating effect analyses were performed to evaluate the robustness of BGR’s effect on 365-day mortality. The study found a cumulative 365-day mortality rate of 34.2% among CKD stages 1–4 patients, with a 2.43-fold increase in the risk of death associated with BGR and at least a 44% increase in the risk of death for each unit increase in BGR (P = 0.022). A significant nonlinear relationship was identified, showing a stepwise change in the risk of death with a marked increase in the slope of the curve for BGR values below 0.52 and above 0.9 (P < 0.001). Subgroup analyses indicated interactions between BGR and factors such as age, sepsis, first-day antibiotic use, and cerebrovascular disease (P < 0.05). In conclusion, this study confirms that BGR is a significant and stable predictor of 1-year mortality risk in patients with CKD stages 1–4. Interventions aimed at timely adjustment, correction of metabolic imbalances, reduction of inflammation, and management of BGR levels are beneficial for reducing mortality in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is a progressive disease, and its burden has not declined as much as that of many other important non-communicable diseases over the past three decades. The global prevalence of CKD is approximately 9.1% 1, and its prevalence in Southeast Asia ranges from 4.7 to 17.4%2. In 2017, 12 million patients died of CKD, and an additional 14 million deaths from cardiovascular disease were attributed to impaired renal function1.CKD is ranked as the 12th leading cause of death owing to the disease burden in 20213. CKD is categorized according to the degree of renal decompensation into stages 1–5, with stages 1–4 being the early and intermediate stages. Despite appropriate treatment, these patients face a high risk of death. To better predict and manage the prognosis of these patients, especially those who are critically ill, an ongoing search for biomarkers that can predict the risk of death is essential to improve clinical outcomes and guide therapeutic strategies.

Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) and glucose are commonly used biochemical indicators in clinical practice and are metabolic waste products of protein metabolism in the body, produced by the liver and excreted by the kidneys, reflecting the state of renal function and protein metabolism. Studies have confirmed that BUN is a risk factor for acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients who require renal replacement therapy4,5, which can trigger immune dysfunction by promoting hypercatabolism and activating neurohumoral mechanisms, thereby increasing the risk of death in critically ill AKI patients6. Blood urea nitrogen can be used as a predictor of mortality in myocardial infarction7,8 and is strongly associated with in-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients with intracranial hemorrhage in the ICU9. Glucose is the basic unit of cellular metabolism that generates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via oxidative phosphorylation to supply energy for cellular activities. Adequate sugar intake can avoid the use of proteins for energy supply, thus protecting the structure and function of muscles and other important proteins and reducing BUN production. In addition, tight glycemic control (80–110 mg/dl) reduces morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients10. Plasma glucose level on admission is an independent risk factor for short- and long-term prognosis after myocardial infarction11,12, and the reduction in mortality in critically ill patients may benefit from controlling the upper limit of the patient’s target glucose level (145 mg/dl )13. However, low blood glucose levels, inadequate sugar intake, or metabolic abnormalities leading to increased protein catabolism and elevated BUN levels can also affect patient prognosis. Few studies have investigated whether the ratio of blood urea nitrogen to glucose (BGR) can predict the risk of death. In recent years, the blood urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio (BAR) has been studied extensively, and it has been significantly associated with increased all-cause mortality in patients with AKI14 and has been associated with good mortality predictive ability for a variety of diseases, including pneumonia, sepsis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic heart failure15,16,17,18. Theoretically, BAR, which is the ratio of one risk factor dimension to physiological indicators, and BGR, which is the ratio of two mortality risk factor dimensions, may be associated with mortality in patients with CKD, and their specific correlations and mechanisms require further investigation.

Therefore, we obtained information on patients with CKD stages 1–4 from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV version 2.2 [MIMIC-IV (v2.2)] database19 to conduct a cohort study to investigate the relationship between BGR and the risk of death in critically ill patients with CKD stages 1–4. risk, helping us better understand the role of this ratio in the course of critically ill patients with CKD stages 1–4 and potentially providing clinicians with new prognostic assessment tools for early identification of high-risk patients for more personalized and effective treatment regimens.

Methods

Database introduction

The data in this study were obtained from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV version 2.2 [MIMIC-IV (v2.2)] database, which is the result of collaboration between the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).This database covers information from BIDMC for all patients who were admitted to either the emergency department or an ICU between 2008 and 2019, with all patient Death information was followed up for one year after discharge from the hospital. To protect patient privacy, all personal information was de-identified using randomized codes instead of patient identification; therefore, we did not require patients’ informed consent and ethical approval. The MIMIC-IV (v2.2) database can be downloaded from the Physionet Online Forum (MIMIC-IV v2.2 (physionet.org)). To apply the database to clinical research, the first author of this study, Shenghua Du, completed the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) course and passed the “Conflict of Interest” and “Data or Sample Study” exams (ID: 59379461). After signing the data use agreement, the research team was authorized to use the database and extract the data.

Patient selection criteria

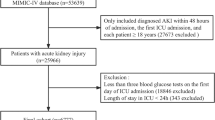

MIMIC-IV (v2.2) recorded 431,231 hospital and 73,181 ICU admissions. Based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD − 9) codes and International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) codes, excluding patients without any staging, CKD stage 5, and pregnancy-related nephropathies, we extracted 6,569 patients with CKD stages 1–4 admitted to the ICUs, excluding patients who were admitted to the hospital for less than 24 h, retaining the demographic information of the first admission, and extracting the in-hospital vital signs, laboratory indicators, and comorbidity information (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

BGR was the primary study variable, and patient death on day 365 was the study endpoint. Potential confounders were extracted, including demographics (age, sex, and race), vital signs[mean temperature(Temp), mean respiration(Resp), heart rate(HR), and average blood pressure(Mbp)], laboratory parameters [hemoglobin (HGB), white blood cell count (WBC), international normalized ratio (INR), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), glucose (Glu), albumin (Alb), anion gap (AG), calcium, sodium, potassium], comorbidities [myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), cerebrovascular disease (CVD), diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic lung disease (CPD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), malignant cancer (MC), severe liver disease (SLD)], and Sepsis and AKI stage 7-day occurrence. Information on bacterial cultures and the use of antibiotics on day 1 was also extracted. Unfortunately, the database could not extract CKD1-4 patients separately by stage. Data were extracted using PostgresSQL (v13.13.1) and Navicat Premium (version 16) in Structured Query Language (SQL).

Management of missing data and outliers

Missing confounder variables were detected during data cleaning and multiple interpolation was used to solve the complex problem of missing values20. When confronted with missing data, a common question is what proportion of missing data is acceptable, and predicting the availability of missing and/or confounding variables associated with missing data may be an important consideration. Even if there is a very high proportion of missing data (up to 90%) in terms of the estimation accuracy of data analysis, the fraction of missing information is more important than the fraction of missing data, thereby reducing unbiased estimation21.

Statistical analysis

All data in this study were statistically analyzed using the R statistical package (http://www.R-project.org, R Foundation) and Fengrui statistical software version 1.9.2. A two-tailed test was used, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Several covariates were collected with missing data, with a high percentage of Alb and INR missing data, and multiple interpolation was performed on the missing data using Bayesian regression to minimize bias. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (%). Raw data were analyzed for baseline characteristics, continuous variables were compared using t-tests or one-way ANOVA, and categorical variables were tested using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. BGR values were calculated for interpolated data, potential risk factors were analyzed using one-way Cox regression, and variables with p values less than 0.1 were included in the multifactorial COX regression analysis. In the multifactorial regression analysis, the BGR was quartile-stratified in order of magnitude and modeled for multivariate analysis, and the model was gradually adjusted based on whether the HR was less than 1.0 in Table 2 of the univariate analysis, vital signs, laboratory tests, and comorbidity groupings. Model 1 was not adjusted; model 2 was adjusted according to gender, Abp, Temp, HGB, Alb, calcium, and antibiotics day1; model 3 added Age, HR, Resp, WBC, INR, BUN, AG, Cr, and potassium to model 2 adjustment; Model 4 added MI, CHF, PVD, CVD, DM, CPD, PUD, MC, SLD, sepsis3, aki stage 7 day, bacterial culture based on model 3. We also applied a restricted cubic spline regression model and inflection point analysis to analyze the linear relationship between BGR and 365-day mortality and applied the K-M curve to analyze the changes in mortality rate using BGR inflection point stratification. Further stratification was based on Age, BRG inflection point, sex, sepsis3, antibiotics day1, bacterial culture, CHF, CVD, CPD, DM subgroups, and mediation analyses to investigate the robustness of the effect of BRG on 365-day mortality in patients with CKD 1–4 stage.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

A total of 6380 patients were finally included in the study, including 3954 (63.2%) males and 2426 (36.8%) females, aged 75.5 ± 12.3 years. The missing rates for serum albumin, INR, and blood calcium levels in the included patients were 60.4%, 7.9%, and 7.3%, respectively. The missing rates of antibiotic use on the first day and bacterial culture results were 33.2%, and the remaining variables were below 5%. Cox regression was used to perform multiple interpolations with five interpolated sets of five, and the first set of data was extracted and analyzed. The cumulative 365-day mortality rate of patients with chronic kidney disease stages 1–4 was 34.2% (Table 1). Age and HR were higher in deceased patients than in survivors (P < 0.001), and Abp was lower in deceased patients than in survivors (P = 0.01). WBC, INR, BUN, Cr, AG, sodium, and potassium levels were higher in deceased patients than in survivors (P < 0.001); however, the levels of HGB and Alb were low (P < 0.001). Among the deceased patients, the prevalence of sepsis and AKI stage 7 days was 60.6% and 73.4%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of the surviving patients (P < 0.001), and the proportion of comorbidities (comorbidities) was higher, in which CVD, CPD, PUD, MC, and SLD were statistically significant (P < 0.001). It is worth mentioning that the prevalence of DM was higher in the study population, with the prevalence of DM in surviving and deceased patients being 50.6% and 48%, respectively (P = 0.0046).

Univariate Cox analysis

Cox univariate regression analysis showed a 2.43-fold increase in the risk of death based on the urea nitrogen to glucose ratio (P < 0.001; Table 2). Each unit increase in Resp was associated with a 7% increase in the 365-day risk of death, and each 1 mmHg increase in Abp was associated with a 2% decrease in the risk of death (HR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99), P < 0.001.Among the laboratory indices, the risk of death increased by 1%, 7%, and 9% for each unit increase in BUN, Cr, and AG, respectively. HGB and Alb reduced the risk of death by 4% and 35%, respectively, but the effect of Glu was not statistically significant. Except for DM, patients had HRs greater than 1 for comorbidities, including CHF 1.62 (95% CI: 1.49–1.77), SLD 2.13 (95% CI: 1.78–2.55), and MC was 2.05 (95% CI: 1.84–2.27). The higher the staging grade in AKI stage 7-day patients, the higher the 365-day risk of death, with HRs of 2.71 (95% CI: 2.42–3.03) for AKI stage 3 and 1.54 (95% CI: 1.42–1.68) for patients with sepsis-3, P < 0.001. Patients who were administered antibiotics on the first day had a 33% reduction in the risk of death, and bacterial culture-positive patients had a 44% increase in the risk of death.

Cox multifactor analysis

In the stratified and multivariate-adjusted analyses of BGR, BGR was significantly associated with 365-day patient death (Table 3), with each unit increase in BGR associated with at least a 44% increase in the risk of death (P = 0.022).After stratification by BGR quartile, the subgroup with the highest BGR (Q4) had a 1.13-fold higher risk of 365-day death than the subgroup with the lowest BGR (Q1) (P < 0.001).

Restricted cubic spline regression model

The curve showed a nonlinear relationship between BGR and 1-year mortality (P < 0.001;Fig. 2a). Inflection point analysis showed that the slope of the curve before the BGR inflection point of 0.52 was HR 13.025 (3.375–3.884), P = 0.0154; the curve was flat between 0.52 and 0.90, with a slope of HR 8.57 (0.653–4.305), P = 0.2824, which was statistically insignificant; and the slope of the curve was significantly increased when the BGR was above 0.9, P < 0.001 (Table 4; Fig. 2b).

(a) Linear dose-response relationship between BGR and 365 days mortality. (b) Breakpoint Analysis Curve, Break Point 1 = 0.52, Break Point 2 = 0.9. (c) Kaplan-Meier curve illustrating the relationship between BGR and 365-day mortality. (d) Kaplan-Meier curve demonstrating the association between Sepsis-3 and 365-day mortality. The curves along the shaded areas depict the estimated values and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Survival analysis

Survival curves showed the highest probability of survival in patients with BGR < 0.52, which declined more slowly over time. Patients with BGR between 0.52 and 0.9 had a survival rate of 51.6% (362/701) at 300 days, and with BGR greater than 0.9, the 300-day survival rate declined to 44.3% (74/167), and the difference in survival between the three groups was significant (P < 0.001; Fig. 2c). The 300-day survival rate was 62.2% (2092/3361) in patients with combined Sepsis3 and 73.4% (2215/3019) in patients without combined sepsis (P < 0.001; Fig. 2d).

Subgroup and mediation analysis

Subgroup analyses of the incidence of death based on BGR included age, sex, sepsis, whether antibiotics were administered on the first day, bacterial culture results, 7-day AKI staging, and whether there was a combination of CHF, CPD, CVD, and DM. Bacterial culture, 7-day AKI staging, CHF, CPD, and DM subgroups had p-values of 0.202–0.998, with no interaction (Fig. 3), whereas there was a statistically significant difference in age, sepsis, antibiotics on the first day, and CVD subgroups (P < 0.05),with an interaction effect. Mediation effect analysis of the effect factors with interaction showed a direct effect value of 1.8048 for BGR and indirect effect values of 0.0423, 0.4793, -0.3669, and 0.3430 for age, sepsis, first-day antibiotic use, and CVD, respectively (P < 0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, we investigated data from the mimiciv2.2 database of patients admitted to the ICU with CKD stages 1–4 and found a high 365-day mortality rate of 34.2%, with a high prevalence of comorbid CHF, DM, and CPD (51.8%, 49.7%, and 30.2%, respectively). Antibiotics were administered to 89.2% of patients on the first day, indicating a high prevalence of infections in patients admitted to the ICU with CKD stages 1–4, with a positive bacterial culture of 21.4%, a prevalence of sepsis of 52.7%, and an incidence of 7-day acute kidney injury of 66.2%. Univariate analysis confirmed that all of these factors were associated with 365-day mortality. In addition, this study found that vital signs and other laboratory indicators, except blood glucose, were associated with the study endpoint indicators. More notably, the main observed variable of the study, BGR, had an HR of 3.43 (95% CI: 2.95–3.98) in the univariate Cox analysis, which was higher than all the impact factors. Using stratified multivariate modeling, we further confirmed the robustness of BGR in predicting the risk of death.

As mentioned in the introduction, BUN and Glu are commonly used biochemical indicators in clinical practice. BUN is a waste product of protein metabolism, and Glu is metabolized to generate adenosine triphosphate to supply energy for cellular activities. Adequate sugar intake and normal metabolism can reduce the production of BUN. As early as 1985, urea nitrogen was recognized as a key factor for patient survival after resuscitation for cardiac arrest combined with coronary artery disease22. In recent years, there have been more relevant studies6,23,24,25, and critically ill patients are more likely to have comorbid metabolic abnormalities; Kevin Beier reported that patients with BUN > 40 mg / dl had a 4.12-fold increased risk of death relative to patients with BUN 10 ~ 20 mg / dl26. Our study did not stratify BUN, but univariate analysis showed a 1% increase in the risk of death for every 1 mg/dl increase in BUN, consistent with previous studies. The possible mechanisms include the cytotoxic effects of BUN, inflammation, and oxidative stress, which can lead to tissue cell damage27,28. Most studies have similarly confirmed that the ideal control of Glu reduces mortality10,13. However, the Mikhail Kosiborod study found no significant association between elevated blood glucose levels and mortality in elderly (mean age 79.4 years) hospitalized heart failure patients29, which is consistent with the results of our study population (Wald’s test, P = 0.705).This may be related to the fact that both study populations were of an advanced age and had a high number of comorbidities. Currently, there is a growing body of research exploring the relationship between the blood urea nitrogen-to-albumin ratio (BAR), the blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio, and disease prognosis14,30,31,32, primarily focusing on the dimensions of protein metabolism and renal function. Studies have demonstrated that these markers are useful in evaluating disease outcomes. Unfortunately, we were unable to find any literature on the blood urea nitrogen-to-glucose ratio (BGR) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). In our daily management of critically ill patients, we observed that many experienced decreased serum albumin and increased non-renal blood urea nitrogen (BUN) due to factors such as poor nutritional intake, infection, and organ decompensation. This raises the question: Are these changes linked to an imbalance in energy metabolism in these patients? And how does this imbalance relate to their prognosis? To investigate this, we selected the albumin metabolites BUN and glucose for the study. In our univariate Cox regression analysis, we found that the hazard ratios (HR) for BUN and BAR were 1.01 (1.01–1.01) and 1.03 (1.03–1.03), respectively. In comparison, the HR for BGR was 3.43 (2.95–3.98), suggesting a stronger association between BGR and 1-year mortality in critically ill patients with stage 1–4 CKD. This finding indicates that BGR may have greater clinical relevance than BUN or BAR, which was further validated in the Cox multivariate model and restricted cubic spline regression model. To further understand the pattern of BGR and 365-day mortality of admission to the ICU CKD1-4, this study conducted restricted cubic spline regression modeling analysis, which showed that the risk of death increased with increasing BGR, and there was a significant nonlinear relationship between the two. Inflection point analysis suggested that the increase in risk of death was relatively flat with a BGR between 0.52 and 0.9, P = 0.3138, and the increase in risk of death was significant with a BGR lower than 0.52 and higher than 0.9(P < 0.001). Survival analysis based on inflection point stratification showed that the higher the BGR, the lower the 1-year survival rate. Therefore, BGR is important for assessing the prognosis and management of ICU patients with CKD stage 1–4. In addition, based on the calculation structure of the BGR ratio, we can presume that elevated BUN is associated with a higher risk of death than elevated blood glucose.

In response to the high prevalence of comorbidities and infections in the included population, this study further validated the consistency and reliability of the findings by repeating the analyses of the main observational variables in different subgroups. The results revealed an interaction between age, sepsis, first-day antibiotic use, CVD and the effect of BGR on mortality. Age is a natural risk factor for patient mortality, and the effect of BGR in this group of patients over 65 years of age may be associated with progressive physiological decline, diminished immune system, comorbidities, and the occurrence of infections. Sepsis is the most common cause of death in most ICUs, resulting in more than 250 thousand deaths per year in the United States33, and sepsis-related deaths accounted for 19.7% of global deaths in 20171; the sepsis prevalence in this study was as high as 52.7%. Survival analysis showed a 300-day survival rate of 62.2%, which was significantly lower than that of non-sepsis patients, of whom 1,327 patients died within one year, accounting for 60.6% (1327/2188) of the patients who died. Sepsis significantly reduces renal blood flow and function, further elevating BUN levels34,35, and its stressful state and inflammatory response lead to increased protein catabolism and decreased synthesis36. Meanwhile, the release of glucagon, catecholamines, and cortisol hormones caused by sepsis leads to stress, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance36. Although timely and rational antibiotic administration can alleviate the inflammatory response in sepsis, it can significantly improve survival37,38, and patients who received antibiotics on the first day of this study showed a 33% reduction in the risk of death. The mediated effect analysis showed a direct effect value of 1.8048 for BGR and indirect effect values of 0.0423, 0.4793, − 0.3669, and 0.3430 for age, sepsis, antibiotic use on the first day, and CVD, respectively, which provided a more intuitive view of each factor’s 1-year mortality rate in CKD stage 1–4 effect.

In this study, we analyzed and evaluated the risk of BGR in predicting death within 365 days of CKD stage 1–4 using multiple statistical methods and approaches, showing good consistency and stability, which may be superior to BUN and BAR in assessing patients’ prognosis and provide guidance for clinical treatment. To the best of our knowledge, no literature has been reported on the association between BGR and CKD. This study had some limitations. First, as mentioned previously, most patients with CKD were diagnosed with stage I to IV chronic kidney disease, and we were unable to analyze CKD with more specific stages, which is a limitation of retrospective studies that cannot exclude as many confounding factors as possible. Second, regarding the effect of missing confounding variables on the study results, we used multiple interpolations to reduce the loss of confounders, avoid greater bias, and stabilize the results. Third, the study had a high mean patient age, and further studies with more age groups and time are needed to validate our conclusions. In addition, this study was a single-center clinical study, and the study population had severe disease; therefore, the prognosis of patients from different regions and younger patients requires further study.

In conclusion, our findings reveal the validity and stability of BGR in predicting the risk of death within 365 days of CKD1-4 stage, and intervening in the level of BGR may be helpful in reducing mortality in this patient population. Critically ill patients with CKD1-4 stage are prone to sepsis, which is significantly associated with the risk of death. Therefore, timely adjustment, correction of protein and glucose metabolism imbalance, reduction of inflammatory response, and control of BGR between 0.52 and 0.90 may be beneficial in reducing mortality. However, the level of BGR should be controlled to improve patient survival. Further analysis is needed to determine whether this is the cutoff value for the relatively flat phase of risk increase, as shown by the BGR inflection point analysis curve in this study.

Data availability

This research analyzed datasets that were publicly accessible (MIMICIV 2.2). Although the datasets used in the study were not publicly available during the study period, they are currently available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Bikbov, B. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 395, 709–733 (2020).

Liyanage, T. et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Asia: A systematic review and analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 7, e007525 (2022).

Naghavi, M. et al. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 403, 2100–2132 (2024).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Clinical factors in predicting acute renal failure caused by rhabdomyolysis in the ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 31, 1062–1066 (2013).

Perianayagam, M. C., Seabra, V. F., Tighiouart, H., Liangos, O. & Jaber, B. L. Serum Cystatin C for prediction of Dialysis requirement or death in acute kidney injury: A comparative study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 54, 1025–1033 (2009).

Kazory, A. Emergence of blood Urea nitrogen as a biomarker of neurohormonal activation in heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 106, 694–700 (2010).

Richter, B. et al. Blood Urea nitrogen has additive value beyond estimated glomerular filtration rate for prediction of long-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 59, 84–90 (2019).

Zhu, Y. et al. Blood urea nitrogen for short-term prognosis in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 9396088 (2022).

Luo, H. et al. Blood creatinine and Urea nitrogen at ICU admission and the risk of in-hospital death and 1-year mortality in patients with intracranial hemorrhage. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 967614 (2022).

Van Den Berghe, G. et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl. J. Med. 354, 449–461 (2006).

Kosiborod, M. et al. Admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: Implications for patients with and without recognized diabetes. Circulation 111, 3078–3086 (2005).

Malmberg, K., Norhammar, A., Wedel, H. & Rydén, L. Glycometabolic state at admission: Important risk marker of mortality in conventionally treated patients with diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction: Long-Term results from the diabetes and Insulin-Glucose infusion in acute myocardial infarction (DIGAMI) study. Circulation 99, 2626–2632 (1999).

Finney, S. J. Glucose control and mortality in critically ill patients. JAMA 290, 2041 (2003).

Shi, Y. et al. Blood Urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio is associated with all-cause mortality in patients with AKI: A cohort study. Front. Nutr. 11, 1353956 (2024).

Ryu, S. et al. Utility of the blood Urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio as a prognostic factor of mortality in aspiration pneumonia patients. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 43, 175–179 (2021).

Cai, S. et al. Association between blood Urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio and in-hospital mortality of patients with sepsis in intensive care: A retrospective analysis of the fourth-generation medical information Mart for intensive care database. Front. Nutr. 9, 967332 (2022).

Zeng, Z. et al. Blood Urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio: A good predictor of in-hospital and 90-day all-cause mortality in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 22, 476 (2022).

Lin, Z. et al. Blood Urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio as a new prognostic indicator in critical patients with chronic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 9, 1360–1369 (2022).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10, 1 (2023).

Austin, P. C., White, I. R., Lee, D. S. & Van Buuren Missing data in clinical research: A tutorial on multiple imputation. Can. J. Cardiol. 37, 1322–1331 (2021).

Madley-Dowd, P., Hughes, R., Tilling, K. & Heron, J. The proportion of missing data should not be used to guide decisions on multiple imputation. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 110, 63–73 (2019).

Goldstein, S. et al. Predictive survival models for resuscitated victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with coronary heart disease. Circulation 71, 873–880 (1985).

Schriefl, C. et al. Blood Urea nitrogen kinetics in the early postcardiac arrest phase are associated with clinical outcome: A retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 39, 405–407 (2022).

Jawad, B. N. et al. Development and validation of prognostic machine learning models for short- and long-term mortality among acutely admitted patients based on blood tests. Sci. Rep. 14, 5942 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Prognostic value of blood Urea nitrogen for Short-Term mortality in patients with infective endocarditis. Infect. Dis. Ther. 12, 2353–2366 (2023).

Beier, K. et al. Elevation of blood Urea nitrogen is predictive of long-term mortality in critically ill patients independent of normal creatinine*. Crit. Care Med. 39, 305–313 (2011).

Zhang, Z., Yang, X. Y. & Cohen, D. M. Urea-associated oxidative stress and Gadd153/CHOP induction. Am. J. Physiol. -Ren Physiol. 276, F786–F793 (1999).

D’Apolito, M. et al. Urea-induced ROS cause endothelial dysfunction in chronic renal failure. Atherosclerosis 239, 393–400 (2015).

Kosiborod, M. et al. Elevated admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation 119, 1899–1907 (2009).

Ugajin, M., Yamaki, K., Iwamura, N., Yagi, T. & Asano Blood Urea nitrogen to serum albumin ratio independently predicts mortality and severity of community-acquired pneumonia. Int. J. Gen. Med. 583 https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S33628 (2012).

Lin, H. J. et al. Elevated blood Urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio increased the risk of hospitalization and all-cause death in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 98, 487–492 (2009).

Brookes, E. M. & Power, D. A. Elevated serum urea-to-creatinine ratio is associated with adverse inpatient clinical outcomes in non-end stage chronic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 12, 20827 (2022).

Martin, G. S., Mannino, D. M. & Moss, M. The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis*. Crit. Care Med. 34, 15–21 (2006).

Seely, K. A. et al. Hemodynamic changes in the kidney in a pediatric rat model of sepsis-induced acute kidney injury. Am. J. Physiol. -Ren Physiol. 301, F209–F217 (2011).

Waltz, P., Carchman, E., Gomez, H. & Zuckerbraun, B. Sepsis results in an altered renal metabolic and osmolyte profile. J. Surg. Res. 202, 8–12 (2016).

Kushimoto, S. et al. Impact of blood glucose abnormalities on outcomes and disease severity in patients with severe sepsis: An analysis from a multicenter, prospective survey of severe sepsis. PLoS ONE. 15, e0229919 (2020).

Weinberger, J., Rhee, C. & Klompas, M. A. Critical analysis of the literature on Time-to-Antibiotics in suspected Sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 222, S110–S118 (2020).

Im, Y. et al. Time-to-antibiotics and clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis and septic shock: A prospective nationwide multicenter cohort study. Crit. Care. 26, 19 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Dr. Jun Lyu (Department of Clinical Research, the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine Informatization) for the study design. Liu Jie (People’s Liberation Army of China General Hospital, Beijing, China) and Dr. Qilin Yang (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University) for helping with the statistical support and data extraction.The authors would like to thank all the reviewers who participated in the review, as well as MJEditor (www.mjeditor.com) for providing English editing services during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

The National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC2304800), Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (No. 2023A03J0539, 2023A03J0992, 2024A03J0580).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.X.H. was responsible for funding, reviewing, and editing this manuscript. S.H.D. and N.S. initiated and designed the study, and drafted and edited the manuscript. Z.X. Y., J.H. L., Y.Y. J., and J.W. reviewed, critiqued, and revised the original paper. All authors reviewed the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, S., Yu, Z., Li, J. et al. Association of blood urea nitrogen to glucose ratio with 365-day mortality in critically ill patients with chronic kidney disease: a retrospective study. Sci Rep 15, 6697 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91012-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91012-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prognostic value of albumin-corrected anion gap in severe chronic kidney disease with sepsis: association with mortality and clinical outcomes

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)