Abstract

How humans estimate causality is one of the central questions of cognitive science, and many studies have attempted to model this estimation mechanism. Previous studies indicate that the pARIs model is the most descriptive of human causality estimation among 42 normative and descriptive models defined using two binary variables. In this study, we build on previous research and attempt to develop a new descriptive model of human causal induction with multi-valued variables. We extend the applicability of pARIs to non-binary variables and verify the descriptive performance of our model, pARIsmean, by conducting a causal induction experiment involving human participants. We also conduct computer simulations to analyse the properties of our model (and, indirectly, some tendencies in human causal induction). The experimental results showed that the correlation coefficient between the human response values and the values of our model was r = .976, indicating that our model is a valid descriptive model of human causal induction with multi-valued variables. The simulation results also indicated that our model is a good estimator of population mutual information when only a small amount of observational data is available and when the probabilities of cause and effect are nearly equal and both probabilities are small.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans can discover causal relationships inductively from observational (non-interventional) data without conscious calculation, producing insights accurate enough to form the basis of modern sciences such as physics, chemistry, biology, and medicine even before the development of statistical methods for evaluating relationships among variables1. By learning and utilising causal knowledge, humans can predict and sometimes manipulate future events. In this sense, causal knowledge plays a central role in human cognitive functioning2,3, and understanding the human cognitive system that infers causality is a critical issue in cognitive science.

Causal induction is the cognitive process in which we inductively infer a relationship between events from observational data, and many psychologists and cognitive scientists have attempted to explain, using mathematical models, how humans detect causal relationships between events. Representative mathematical models include the ΔP rule and the causal power model, which estimate the causal intensity between events, as well as the causal support model, which estimates the likelihood of causal structures rather than causal strengths1,4,5. These models were derived from the perspective of mathematical rationality; in other words, they are normative models that represent how humans should infer causality in order to satisfy the rationality standards. Meanwhile, Hattori and Oaksford proposed, after pointing out that a normative definition of causality may be irrelevant to human causal cognition, a two-stage hypothesis for modelling human causal induction in terms of descriptiveness, which explains how humans infer causal relationships6. The two stages are (1) extracting plausible causal event pairs through observation (the heuristic stage) and (2) testing whether a causal relationship truly exists by performing intervention manipulations on the extracted event pairs (the analytic stage). They also claimed that what humans perform during the heuristic stage is the detection of covariation between events. They then derived the dual-factor heuristic (DFH) model by applying an extreme manipulation they call the extreme rarity assumption to Pearson’s correlation coefficients. They also performed a meta-analysis on the 42 mathematical models of causal induction proposed so far, including the above-mentioned normative models, by evaluating the results of cognitive experiments on human causal induction reported in the literature. Their results showed that DFH is the most descriptive model of human causal strength judgments from observational data. Takahashi et al. proposed the proportion of assumed-to-be rare instances (pARIs) model, which is simpler than DFH but offers comparable descriptive performance based on the two-stage hypothesis framework proposed by Hattori et al.6,7,8. Higuchi et al. performed a follow-up of the meta-analysis by Hattori et al. in order to verify the descriptive performance of pARIs and found that pARIs is more descriptive of human judgments than DFH9.

Previous studies on human causal induction have led to the development of elaborate models. However, most of those studies used a framework that estimated the causal strength of two events based on the frequencies with which each event did or did not occur. The frequencies are represented by the 2 × 2 contingency table shown in Table 1.

In this table, N(C = 1, E = 1), N(C = 1, E = 0), N(C = 0, E = 1), and N(C = 0, E = 0) denote the occurrence frequencies of each conjunction, designated a, b, c, and d, respectively, with N(C = 1), N(C = 0), N(E = 1), and N(E = 0) denoting the marginal frequencies, and N(Ω) the total frequency. As Table 1 shows, causal induction that utilises the 2 × 2 contingency table is equivalent to inferring a causal relationship between two binary variables. This simplified elementary framework has some advantages, including ease of verification through experimentation and enabling a focus on fundamental problems by ignoring complex factors. However, this framework also has some disadvantages, including the possibility of ignoring essential factors and their interactions, as well as the inability to address the complexity of problems that humans deal with in the real world. For example, humans can infer the strength of the causal relationship between “taking a specific kind of medicine” and “improving a specific symptom” by integrating the influences of each amount of medicine intake. However, it is unclear how humans perform this kind of comprehensive inference, and the framework that utilises the 2 × 2 contingency table does not directly answer this question. In contrast, introducing a framework for multi-valued variables would directly answer this question.

In this study, we consider a framework in which the target of causal induction is generalised to non-binary variables (that represents not just occurrence/non-occurrence of events). We then propose an extended model of pARIs that can address such a framework. This extension improves the model’s generality by making the model capable of addressing observational data of continuous variables in an approximate way, as well as observational data that include missing values and categorical variables (this point is discussed in more detail below). Marsh and Ahn addressed the problems of causal induction among multi-valued variables10. Both their study and ours point out the gap between the simplified problems of causal induction that utilise the 2 × 2 contingency table and the problems that people deal with in the real world. Marsh and Ahn focused on how humans classify intermediate or ambiguous values of continuous variables into binary values of occurrence/non-occurrence in the inference process of causal induction tasks10. The present study proposes a method of extension that can handle not only cases in which variables take on intermediate or ambiguous values alongside the two extreme values (occurrence/non-occurrence) but also those in which they take on multiple distinct values (e.g. categorical variables). This approach enables us to address issues that cannot be resolved by classifying intermediate values into either of the two extreme values. In other words, it is particularly useful in cases involving categorical variables, as mentioned earlier, and in causal relationships where either only the intermediate values or only the extreme values promote the outcome.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. In the Sect "Theoretical framework", we describe the theoretical framework of the study and propose six candidates for the best-extended pARIs. In the Sect "Experiment", we analyse how well our model candidates describe human causal induction by conducting a cognitive experiment and then select a model based on the results. In the Sect "Simulation", we perform computer simulations to analyse how accurately the adopted model can estimate population dependence based on the sample data, especially with small samples. In the Sect "Discussion", we summarise and discuss the results. Finally, In the Sect "Conclusion", we present our conclusions.

Theoretical framework

Here, we note two points regarding our use of terminology. First, cognitive science is a research field that attempts to understand human cognitive functions by assuming they are computations or information-processing tasks. We refer to what information processing computes as a “computational goal,” using the terminology of rational analysis, a widely known methodology in cognitive science research11. Second, the term “correlation” commonly refers to linear relationships in statistics but, in a broader sense, refers to any kind of dependency between random variables, including, for example, linear, monotonic and non-linear functional forms. In this study, to avoid confusion, we use the term “dependence” to refer to correlation in this broader sense.

Two-stage hypothesis of causal induction

Hattori and Oaksford argued that causal induction, the process by which humans identify the cause of an event, can be accounted for in two stages: the heuristic stage and the analytic stage6. In the heuristic stage, we narrow down the likely causes from a myriad of events based on observational data on the occurrence or non-occurrence of events. In the analytic stage, we verify whether the narrowed-down candidate causal events are genuine causes by performing intervention operations (i.e. manipulating the occurrence of the candidate causal events). Regarding the effort required to obtain data, the analytic stage, which artificially controls the occurrence of events, is more expensive than the heuristic stage, which merely observes the occurrence of events. In the real world, an event may occur due to a myriad of earlier events, and it is practically impossible for humans to perform costly intervention operations on all of them. In practice, however, humans can obtain observational data on events at a relatively low cost and use these data to narrow down the range of possibilities to a few candidate events that are likely to be the actual causes. In this way, narrowing down based on observation data enables humans to efficiently determine the target of intervention operations.

According to the two-stage hypothesis, the role of the heuristic stage is to detect, using observational data, the strength of suspicion that one event is causally related to another. Note here that if there is a causal relationship between two events, they are generally dependent. In other words, we do not miss genuine causes if we extract events in a dependent relationship. Accordingly, Hattori and Oaksford assume that the computational goal of their model is to detect dependence between events6,12.

The phi coefficient, in Eq. (1), is a typical measure of dependence between two binary variables.

This measure’s value is a special case of Pearson’s correlation coefficient in the 2 × 2 contingency table, as shown in Eq. (2)13. In general, however, linear and dependent relationships are not equivalent, and we must distinguish between the two when extending the contingency table from 2 × 2 to m×n. Linearity is a sufficient condition for dependency; if two events are linearly related, they are dependent, but if two events are dependent, they are not necessarily linearly related. In other words, dependence can capture more relationships between variables than linearity can. For these reasons, in the m×n framework, it is more appropriate to assume dependence detection as a computational goal to allow for more precise event narrowing in the heuristic stage. In this study, assuming that the computational goal in the heuristic stage is dependence detection, we propose a generalised form of pARIs for the m×n contingency table and verify its performance.

pARIs model

Most studies of causal induction have used the 2 × 2 contingency table. In frameworks that utilise the 2 × 2 contingency table, the function of the causal induction model is to estimate the causal strength between two binary variables from four frequencies included in the contingency table, as shown in Table 1. As mentioned earlier, many models have been proposed using this framework to explain human causal induction. Among them, pARIs has the simplest definition but high descriptive performance for human judgments of causal strength. pARIs is defined as follows.

This equation can be transformed as follows:

where N(Ω) is the sum of the frequency of occurrence of all conjunction events. For two events, C = 1 and E = 1, pARIs is the conditional probability value that both events occur given that at least one occurs. N(C = 0, E = 0) is the number of times nothing happened concerning C and E. Counting such a frequency is generally more difficult than counting the number of times something has happened, and such counting can be indefinite8. In this regard, pARIs, which do not include N(C = 0, E = 0) in its definition, have the advantage of ignoring problems related to counting.

Takahashi et al. claimed pARIs to be an efficient approximation of the statistical non-independence under the extreme rarity assumption and that pARIs and DFH behave differently in terms of how they connect the two extreme values of 0 and 18.

pARIs has the same definition as the Jaccard index (also known as Intersection over Union (IoU)), which is a standard measure of similarity between finite sets14. This index is known as one of the standard measures for the similarity of habitats in ecology15, and in the field of machine learning, it is used as a representative measure of prediction accuracy, particularly in object detection and segmentation tasks16. Furthermore, pARIs is the most basic special case of Tversky’s set-theoretic similarity measure when its parameters α and β are equal to 117. We think that the normativity of pARIs can be explained if we reinterpret the covariation detection between variables as the similarity detection. When event C is the only strong cause of event E, a relationship holds between the two variables, in which E almost always occurs after C occurs (i.e. P(E = 1|C = 1) is large), and C almost always occurs before E occurs (i.e. P(C = 1|E = 1) is large). Such a relationship between two variables implies a high degree of similarity in the behaviour (i.e. the way in which they take on the values of presence or absence) of the two variables. In fact, DFH, which represents the degree of this relationship as the geometric mean of the two conditional probabilities, has the same definition as another measure of similarity known as the ‘Ochiai index’ in ecology18. Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, which is one of the normative indicators of covariation detection and is defined as the ratio of the covariance of two variables and the product of their standard deviations, also indicates the degree to which two variables tend to show similar behaviour. In fact, the cosine similarity \(\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}(\text{x},\:\text{y})=\frac{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{N}{x}_{i}{y}_{i}}{\sqrt{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{N}{x}_{i}^{2}}\sqrt{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{N}{y}_{i}^{2}}}\), which is the standard similarity measure between vectors, is called the ‘centred cosine similarity’ when each vector is normalised by its mean value and is equivalent to Pearson’s correlation coefficient \(\:r=\frac{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{N}\left({x}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{x}\right)\left({y}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{y}\right)}{\sqrt{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{N}{\left({x}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{x}\right)}^{2}}\sqrt{{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{N}{\left({y}_{i}-\stackrel{-}{y}\right)}^{2}}}\)19.

In addition, we think that the normative status of pARIs can be explained in the framework of probabilistic logic. The above relationship between variables C and E can be logically expressed as the two propositions: ‘If C, then E’ and ‘If E, then C’. According to de Finetti’s subjective probability theory20, which is a normative and descriptive theory of probabilistic logic (see, e.g.21) , the probability of these two propositions simultaneously true is the ‘biconditional probability (\(P\left(\right(E\left|C\right)\wedge\:\left(C\right|E\left)\right)\)),’ and pARIs is identical to this8,22,23,24,25.

Six model candidates for extended pARIs

We have already pointed out the problems with the elemental causal induction framework that utilises the 2 × 2 contingency table. Here, we consider a framework in which the subject of causal induction is two multi-valued variables and propose an extended model of pARIs for this framework aimed at improving the model’s generality in three respects. First, the model can address observational data on continuous variables thriftily. The assumption that even a vast number of candidate causal variables can take continuous values is considered unrealistic from the standpoint of observation cost, computational resources and memory capacity. In general, we need dedicated instruments to capture the values of continuous variables, and it may be beyond human cognitive limits to accurately memorise and use those values for inference. However, humans can roughly discretise continuous values based on their senses (e.g. hot, mild, and cold temperature). By doing so, humans can save much of the costs required during inference, including observation costs, computational resources, and memory capacity. In this way, humans can employ a minimal framework depending on the problem involved, and we can consider binary variables to be the most extreme case of such thrift. Extending the framework to multi-valued variables can account for efficient causal induction that humans perform. Second, the model can handle observational data, even when they contain missing values. Here, “missing values” refers to instances where a variable’s value is indeterminate due to limitations in observability, forgetting, or other factors. In the m×n framework, missing values can be addressed by introducing a third value (realisation) for the variables, which indicates that their occurrence is unknown21. We can then consider how humans complement missing data, such as by treating it as evidence to increase or decrease the estimated causal strength or ignoring it altogether. Third, the model can deal with categorical variables. Here, categorical variables are those for which there is no ordinal relationship between values. Its observational data might include data on the use of the same type of fertiliser made by different manufacturers and data on plant growth. We can consider the question of how humans make integrated assessments of the efficacy of a certain type of fertiliser based on such data.

In this study, we focus on the first of the three points and deal with causal induction when there is some ordinal relationship among the values of multi-valued variables. To simplify the procedure for verification by experiment or simulation, we consider the case of a minimal extension in which a candidate cause is three-valued, and an outcome variable is binary. In this case, a 3 × 2 contingency table, such as Table 2, represents the co-occurrence information between variables.

Let a candidate causal variable C take the values large (C = 1), small (C ≈ 0.5), and absent (C = 0), where the expressions “large” and “small” imply only an ordinal relationship between them. We let N(C = 1, E = 1), N(C = 1, E = 0), N(C ≈ 0.5, E = 1), N(C ≈ 0.5, E = 0), N(C = 0, E = 1), and N(C = 0, E = 0) denote a, b, m, n, c, and d, respectively.

As mentioned in the “Theoretical framework” section, pARIs is the conditional probability that two events “occur at the same time” given that “at least one of them occurs.” We propose an extended model of pARIs that applies this definition to the m×n contingency table. For this purpose, we consider how humans deal with the “different kinds of occurrences (e.g. large and small quantities)” taken by variables. There are a total of three patterns for dealing with these differences: (1) Humans lump together multiple values that correspond to occurrence, (2) Humans distinguish between multiple values and use only one of them for inference, (3) Humans distinguish between multiple values and use all of them for inference. To propose an extended model that is most compatible with human estimation in the Sect "Experiment", we proposed six model candidates for extended pARIs that align with these patterns.

Hereafter, c′ denotes that a cause is present (i.e. C ≠ 0), and e′ denotes that an outcome is present (i.e. E ≠ 0). For example, in Table 2, c′ is “C ≈ 0.5 or 1”, and e′ is “E = 1”. The model candidate corresponding to the pattern (1) is defined as pARIs when focusing on c′ and e′ and is shown in Eq. (8). Applying this definition to the 3 × 2 contingency table yields Eq. (9).

This model candidate is equivalent to the pARIs of 2 × 2 contingency tables obtained by combining multiple rows or columns of m×n contingency tables. For this reason, we refer to this model candidate as pARIsmerge.

The model candidates corresponding to patterns (2) and (3), as opposed to (1), distinguish between multiple values that correspond to occurrence. Let ΩX denote the sample space of variable X (i.e. the set of possible values), while ΩX′ denotes the sample space excluding values that correspond to non-occurrence (i.e. ΩX′ := ΩX∖{0}). For the 3 × 2 contingency table, ΩC={0, 0.5, 1}, ΩE={0, 1}, ΩC′={0.5, 1} and ΩE′={1}. We define the second model candidate as the pARIs value, that is, Eq. (10) for all pairs of i in ΩC′ and j in ΩE′.

If we apply this definition to the 3 × 2 contingency table, we can compute the values of pARIs for two pairs: C = 1 and E = 1, and C ≈ 0.5 and E = 1.

We define pARIsmean, pARIsweighted, pARIsmax, and pARIsmin as the arithmetic mean, weighted mean, maximum value and minimum value of Eq. (10), and we show them in Eqs. (15), (17), (19), and (21), respectively. Also, if we apply these definitions to the 3 × 2 contingency table, we obtain Eqs. (16), (18), (20), and (22), respectively.

where w1 and w2 are the weights assigned to the two terms, respectively.

pARIsC=i, E=j, pARIsmax, and pARIsmin are model candidates that reflect the assumption that humans distinguish between multiple values that correspond to occurrence and consider only one of them as an estimator of the causal strength. However, pARIsmean reflects the assumption that humans consider all of them as equally important pieces of information and that their mean value is an estimator of causal strength. Table 3 shows the correspondence between the above six model candidates and the ways to deal with different kinds of occurrences (e.g. large and small quantities).

We can identify the extended model that best fits human judgement by calculating the fitness between the model candidates and the experimental result. Depending on which model fits best, we can see how humans employ the co-occurrence information when inferring the causal relationships.

Experiment

We conducted an experiment on observational causal induction with human participants to examine which of the six model candidates for the extended pARIs best fits the results.

Methods

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent by selecting a checkbox in the web application before the experiment. The study did not require ethical approval in accordance with the guidelines of the ethics committee of Tokyo Denki University.

We recruited 63 participants via a crowdsourcing service to conduct a web application–based experiment. Although we did not impose any conditions on the participants, such as their native language, all communication regarding the experiment was conducted in Japanese. We requested that participants use a personal computer to access the web application rather than a smartphone or tablet device. We paid the participants 165 Japanese yen (a little bit more than 1 US dollar) as a reward. We repeated the following procedure for the six stimuli listed in Table 4.

We presented events contained in each stimulus one by one to the participants and asked them to assess the strength of the influence of the cause variable C on the outcome variable E as an integer value of {0, 1, …, 100}, with 0 being no influence at all and 100 being definitely influential, using a slider. The order of presentation was randomised for both the stimuli and the events contained within them. Regarding the cover stories, we designated the candidate causes as the administration of six novel chemical substances named A-88, B-23, C-99, D-64, E-55, and F-98, and the outcomes as the occurrence of abdominal pain, fever, skin rash, and improvement in awakening, physical performance and concentration, and we randomly assigned them to each stimulus.

We show the actual sentences presented to the participants here and explain the details of the experiment. The original sentences were in Japanese, and the sentences shown below are their English translations. Before describing each of the cover stories, we presented the following preamble, which was common to all six stories.

You are a researcher at a pharmaceutical company. The company has conducted experiments to study the effects of six novel substances by administering them to participants. Please use the experimental results that will be presented to infer the effects of these substances. These experiments are entirely fictional and have no connection to any real people or events. Please do not take any notes when working on this task.

For each of the six cover stories, we explained the story, presented the stimulus, and asked for a judgment. We will explain here, as an example, one of the cases where the cause candidate is the administration of the chemical substance A-88, and the effect is abdominal pain. First, we presented the following explanation to the participants.

Administration of the novel chemical substance A-88 may cause abdominal pain. We will present you with the results of an experiment in which multiple participants were administered A-88, and their condition was observed afterwards. For A-88, we will present the results in three levels: ‘large amount’, ‘small amount’, and ‘none’. For abdominal pain, we will present the results in two levels: ‘occurred’ and ‘did not occur’. Check each observation result, click ‘Next’, and repeat the procedure. Once you have reviewed all the observation results, you will be asked to infer and specify the effect of administering the substance A-88 on the occurrence of abdominal pain.

After the explanation, each of the events included in the stimulus was presented one at a time. There were six types of events, as shown below, and we presented these with the frequencies corresponding to a, b, m, n, c, and d in Table 4, respectively.

(a-type) A large amount of A-88 was administered, and abdominal pain occurred.

(b-type) A large amount of A-88 was administered, and no abdominal pain occurred.

(m-type) A small amount of A-88 was administered, and abdominal pain occurred.

(n-type) A small amount of A-88 was administered, and no abdominal pain occurred.

(c-type) no A-88 was administered, and abdominal pain occurred.

(d-type) no A-88 was administered, and no abdominal pain occurred.

Finally, we asked for a response to the following question.

Do you think that administering the substance A-88 will influence the occurrence of abdominal pain? Please answer intuitively on a scale of 0 to 100, with 0 meaning no effect at all and 100 meaning an extremely strong influence.

For this experiment, we used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rS) as a measure of monotonicity and mutual information (MI) as a more comprehensive measure of dependence. We then designed the stimuli as all combinations of cases where the rS and MI values are high, medium, and low, respectively. Because monotonicity is a sufficient condition for dependence, the case in which rS is high but MI is low is not valid; therefore, we used six stimuli. We randomly determined the mapping between stimuli and cover stories, the presentation order of the stimuli, and the presentation order of the events in the stimuli for each participant. To remove outliers, we excluded the top 5% and the bottom 5% of data in terms of the total response time for 57 participants in our analysis.

We calculated the corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) between the mean of the response values and the model candidates. We used a linear mixed model that assumed two random effects (random slope and random intercept) to account for the individual effects of the participants. This model formula is shown in Eq. (23).

Here, \(\:{Y}_{ij}\) is the i-th participants’ response value to the j-th stimulus, \(\:{X}_{j}\) is the model value, and \(\:ϵ\) is the error. \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) are the intercept and slope of the fixed effects and are parameters that are common to all participants. \(\:{\gamma\:}_{0i}\) and \(\:{\gamma\:}_{1i}\) are the intercept and slope of the random effects and differ for each participant. This model means that we assume that the responses of each participant were made based on different baseline and dynamic range settings.

AICc and BIC allow for a relative assessment of multiple models’ descriptive performance but do not indicate the extent to which these models can describe the data. Hence, we also calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient r between the mean of the response values and the model candidates.

Results

Table 4 shows the mean of response values for each stimulus, and Table 5 shows the fit between the mean of response values and the six model candidates except pARIsweighted.

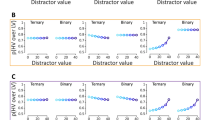

Figure 1 shows the fits for pARIsweighted, that is, the weighted mean of Eqs. (12) and (14) when the weight of the former term is varied. We varied the weight exhaustively over the range [0.0, 1.] in 0.1 increments.

As a result, pARIsweighted best fits the data when the weights of the two terms are both 0.5 (i.e. the arithmetic mean). These results show that pARImean fits the data best when accounting for individual effects and that values of this candidate and mean responses are highly correlated at r = .976.

Simulation

For pARIsmean, which best fits the data among the model candidates of extended pARIs, we performed a simulation to evaluate how accurately the model would estimate a population parameter based on artificial data sampled from a population. Sometimes, model values cannot be calculated from a given sample for reasons such as dividing by zero. To account for this problem, we also evaluated the proportion at which the model values could be computed.

Methods

We employed mutual information, a measure of dependence, as a population parameter. Hereafter, we denote mutual information as a population parameter as MI0 to distinguish it from the mutual information MI calculated from the sample.

First, let N be a sample size, that is, the total frequency of events in each contingency table shown in Table 2. We set sample size N to three different levels {10, 100, 1000} to evaluate the model’s estimation performance across a range from small to sufficiently large sample sizes. To confirm the influence of the rarity assumption, we set P(C = c′) and P(E = e′) at nine levels from 0.1 to 0.9 in increments of 0.1. The c′ and e′ indicate that the cause and effect are present, respectively, and therefore, the rarity assumption holds when P(C = c′) and P(E = e′) are small.

We then determined the population underlying the contingency table from which to sample. Here, the population underlying 3 × 2 contingency tables refers to the probability of each of the six events in Table 2 occurring: P(C = 1, E = 1), P(C ≈ 0.5, E = 1), P(C = 0, E = 1), P(C = 1, E = 0), P(C ≈ 0.5, E = 0), and P(C = 0, E = 0). We determined the marginal probabilities P(C = 1) and P(C ≈ 0.5) for the cause variable based on the uniform distribution.

We then determined the joint probabilities based on the uniform distributions.

The lower bounds of the uniform distributions restrict populations to ones in which the events included in ΩC′ and ΩE′ are in a generative relationship (i.e. ΔP = P(e|c) − P(e|¬c) ≥ 0 for all c∈ΩC′, e∈ΩE′). The upper bounds of the uniform distributions are set to avoid inconsistency with P(C = 1), P(C ≈ 0.5), and P(E = 1). Equations (24) and (25) determine the other joint probabilities.

The set of Eqs. (24), (25), (26), (27), (28), (29), (30), (31) defines a discrete probability distribution and the population from which the contingency tables are sampled. We determined 100,000 discrete probability distributions for each N, P(C = c′) and P(E = e′) combination. We calculated the value of the mutual information MI0 for each discrete probability distribution. We then sampled a contingency table with sample size N from each discrete probability distribution and calculated the model values for each table. Finally, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient r between each model and MI0.

Results

Figure 2 shows Pearson’s correlation coefficients between pARIsmean and MI0 and between MI and MI0, as well as their differences.

When P(C = c′) and P(E = e′) are nearly equal, pARIsmean functions well as the estimate of the population parameter MI0. From the difference of correlation coefficients (right column of the figure), the closer the difference value is to 1 (or red), the better pARIsmean is, and the closer it is to − 1 (or blue), the better the MI is for estimation performance. Focusing on the difference, we find that pARIsmean is superior when the sample size is small (N = 10) and that the difference decreases as the sample size increases (N = 100) and eventually inverts (N = 1000). This inversion is natural because the definitions of MI and MI0 are identical and because MI is a measure of normative dependence, whereas pARIs is a heuristics. Because human memory capacity is limited and immediacy is required, high estimation accuracy with a small sample is an essential feature that cognitive models must satisfy. The results show that pARIsmean has this feature.

The result shown in Fig. 2 is obtained only in cases where the model is calculable for sampled contingency tables. However, the performance of models in population estimation should be evaluated not only in terms of accuracy but also in terms of the range of situations in which they work. Figure 3 shows the proportion of cases where model values can be calculated.

The result indicates that the computable proportions of pARIsmean outperform the proportions of MI in all cases. The result also indicates that the proportion difference is particularly pronounced in the small sample (N = 10) and becomes smaller with increasing sample size (N = 100, 1000). Quantitatively, in the small sample case (N = 10), pARIsmean is calculable in at least 66% of cases, whereas MI is calculable in only 6% of cases at most. In the large sample case (N = 1000), pARIsmean is almost always calculable. In contrast, the proportions of MI are only 48% at minimum and 96% at maximum, and the cases where the calculability of MI is still limited even with such large samples. Figure 3 shows that pARIs is a more efficient population estimation model compared with MI in terms of calculability, which Fig. 2 does not consider.

Discussion

Studies of cognitive models of human causal induction have traditionally focused on binary variables. However, the binary variable framework is inherently limited in its capacity to tackle the complex tasks that people routinely encounter in the real world. Focusing on pARIs, which is the model reported to best replicate human causal induction among the 42 models proposed in a binary variable framework9, this study provided a method for applying pARIs to a multi-valued variable framework. We first presented possible patterns of how humans handle multi-valued variables and introduced six candidate models corresponding to the patterns.

Summary of experimental results

We examined which of the six model candidates best fits the results of our cognitive experiment. As shown in Fig. 1; Table 5, our experiment revealed that pARIsmean best fits human causal induction (r = .976). pARIsmean is the arithmetic mean of the pARIs values calculated for all possible combinations of the two multi-valued variables, excluding cases where both variables are absent. If we explain it in line with the cover story of our experiment, pARIsmean reflects the hypothesis that humans recognise a strong causal relationship when the following two conditions are met. The first condition is that if either low-dose administration or abdominal pain occurs, the other is also likely to occur at the same time, and the second condition is that the same tendency also appears with high-dose administration. Unlike pARIsmerge, which identifies these two types of administration as a single case—namely, the case of administering an arbitrary amount of the substance—pARIsmean distinguishes between the two conditions and takes on a high value when both are met. The high correlation between the model and the experimental data suggests that human causal strength estimation may be based on a method that is similar to pARIsmean. These findings are consistent with those of Marsh and Ahn, whose study showed that people do not ignore intermediate or ambiguous values as unimportant but instead use them as evidence to strengthen or weaken the plausibility of a causal relationship10.

Summary of simulation results

Our simulations revealed that, as Fig. 2 shows, pARIsmean performs well as an estimator of population mutual information when the occurrence probabilities of both variables are small or almost equal and few observational data are available. Furthermore, Fig. 3 shows that pARIsmean outperforms MI itself in that the model works in a greater number of situations. These properties have been reported as properties of pARIs on the 2 × 2 contingency table9, and the simulation results suggest that the proposed model inherits these properties from the original model.

We can also perform rational analysis, a methodology of cognitive science, to evaluate our results11. Rational analysis accounts for the rationalities of cognitive systems in terms of optimality for their environment, based on the assumption that cognitive systems have undergone evolutionary optimisation processes within the environment. Our simulation results show that pARIsmean performs well when the occurrence probabilities of both variables are small or nearly equal and few observational data are available. In the following, we explain how these three situations can be interpreted in the context of rational analysis. First, the situation in which the probabilities of occurrence for both variables are low corresponds to the assumption that, in reality, the probabilities of events subject to causal induction are low (the rarity assumption). This assumption has appeared in various forms in cognitive science, and there is abundant empirical evidence that humans assume rarity6,26,27. Navarro and Perfors provided a theoretical explanation for the assumption (i.e. the basis for considering that rarity is a real-world feature) by showing that sparsity is a logical consequence of category formation, which is based on family resemblance28. Second, regarding the situation where the probabilities of occurrence of both variables are roughly equal, although there is empirical evidence that people assume equal probability in the context of optimal data selection29,30, to our knowledge, there is no theoretical explanation suggesting that this is a property of the environment. However, the rarity assumption leads to the assumption of equal probability. For example, if the probabilities of occurrence of two events, p and q, are both less than 0.5, then their probability difference is at most 0.5. Finally, the situation in which few observational data are available necessarily corresponds to the fact that when rarity holds, it is harder to obtain the data that pARIsmean uses for inference (the frequency with which at least one of the causes or effects occurs). Alternatively, this situation might correspond to the fact that human memory capacity and computational capacities are limited, as Hattori and Oaksford argued6. In addition to environmental properties, rational analysis can include the computational limitations of a system in terms of optimisation constraints. However, such constraints must be minimal and limited to claims that nearly all information-processing theories agree on, including the limits of short-term memory. In summary, the fact that our model describes human causal induction well suggests that human causal induction is optimised for the real-world characteristics of the rarity of events as well as the limitations of human memory and computational capacity.

Relevance to Bayesian networks

pARIs and pARIsmean are descriptive models of how people estimate the causal relationship between a single cause and a single effect. This type of framework, called elemental causal induction1, has been used in a wide range of research, and most of that research has focused on the ‘strength’ of the relationship between two events. Meanwhile, there are also many studies that have focused on estimating the causal relationships between three or more events, and approaches that utilise causal Bayesian networks are especially popular. Causal Bayesian networks are a probabilistic model that employs conditional independence between variables to specify causal structures, and it enables us to infer the effects of interventions based solely on observational data31. Some previous studies have shown that humans judge the effects of interventions based only on observational data, and causal Bayesian networks can account for such human judgements, unlike frameworks that only consider the causal strength between two events32,33. Causal Bayesian networks assume that, conditional on the set of all its direct causes, a variable is independent of all variables that are not effects or direct causes of it, and this assumption is called the causal Markov condition31. Several studies, however, have shown that human judgements partially violate the causal Markov condition and that it is difficult for humans to identify causal structures using observational data alone without strong assumptions of determinism and the sole root cause in the causal systems34,35,36.

Causal Bayesian networks, which can consider multiple multi-valued variables, seem to be superior to elemental causal induction in terms of generality. However, since causal Bayesian networks focus on structures and elemental causal induction focuses on strength, the types of problems they handle are different, and it is not possible to simply compare their generality. Griffiths and Tenenbaum showed how the frameworks of causal Bayesian networks and elemental causal induction can be related to each other as follows1. We assume a causal Bayesian network consisting of three nodes (a cause C, a background cause B, and an effect E) and assign parameters wC and wB to the directed edges of the graph, which correspond to the strength of the causal relationship. We then assume that the probability of occurrence of E is determined by a linear function defined by the values of C and B and their coefficients wB and wC. In this case, Griffiths and Tenenbaum showed that the maximum likelihood estimate of the parameter wC corresponds to ΔP and that, when the noisy-OR function is used in place of the linear function, the estimate corresponds to the causal power model.

Our results may indicate the relationship between ‘strength’ and ‘structure’ in human causal induction from a different context. Takahashi et al. showed that pARIs can be interpreted, based on the definition of independence in probability theory, as an indicator of dependence under the rarity assumption8,9. However, since the descriptive performance of pARIs has traditionally been assessed within the framework of 2 × 2 contingency tables, it was unclear whether its high descriptive performance was merely because pARIs functions as a measure of correlation, or because it functions as a broader measure of dependency. The high descriptive performance of pARIsmean, which is shown in the Sect "Experiment", and the behaviour of pARIsmean as an efficient approximation of MI under rarity and small samples, which is shown in the Sect "Simulation", together support the possibility that humans detect dependencies between variables when performing causal induction. In this way, our results are consistent with the claim of the studies that utilised causal Bayesian networks, which showed that humans infer causality based on conditional independence. In the framework of elemental causal induction, which only considers two variables, cause and effect, there is no third variable for conditioning, and conditional independence is necessarily equal to mere independence. We will need to verify whether “conditional pARIs” and “conditional pARIsmean” can actually describe human causal inductions through cognitive experiments with three or more variables to generalise the framework proposed in this paper and deepen the discussion on its possible relations with causal Bayesian networks.

Future work

This study leaves two main areas for future study. First, although causal induction from multi-valued variables is assumed theoretically in this study, its empirical verification is limited to the specific framework of the 3 × 2 contingency table. Therefore, the conclusions reached in this study do not guarantee generality in any multi-valued variables, indicating the necessity of exhaustive experimentation regarding the size of the contingency table. Exhaustive validation is not a realistic solution, given that validation using large contingency tables would require an excessive cognitive load on the participants. We need to ascertain which properties of our model are independent of table size and assess their intrinsic validity by verifying whether they explain how humans infer causal relationships. Second, our model has the potential to provide a unified explanation of causal induction, regardless of whether the variables are nominal or the observational data contain missing values. We need to conduct additional experiments on the two cases to determine whether the model can describe these data in a unified manner.

Conclusion

pARIs is a descriptive model of human causal induction in the framework of binary variables7,8,9. We improved the model’s generality by extending pARIs to a form applicable to multi-valued variables. We proposed six candidates for the extended model and examined which best fits human judgments obtained in the cognitive experiment. Our analysis revealed that pARIsmean demonstrated an exceptional fit (r = .976) to the data, underscoring its potential in cognitive modelling. We also performed the computational simulations and found that pARIsmean, like the original pARIs, shows better population estimation performance when there are few available observational data and when the probabilities of cause and effect are nearly equal and both are small. These results show that the proposed model is a valid descriptive model of human causal induction on multi-valued variables and also suggest the conditions under which human causal induction is effective.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed in the current study and the codes for analysis and simulations are available on GitHub at the following URL: https://github.com/cyisnf/higuchi2025.

References

Griffiths, T. L. & Tenenbaum, J. B. Structure and strength in causal induction. Cogn. Psychol. 51, 334–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2005.05.004 (2005).

Sloman, S. A. Causal Models: How People Think about the World and its Alternatives (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gershman, S. J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behav. Brain Sci. 40, e253. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X16001837 (2017).

Jenkins, H. M. & Ward, W. C. Judgment of contingency between responses and outcomes. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 79, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093874 (1965).

Cheng, P. W. From covariation to causation: A causal power theory. Psychol. Rev. 104, 367–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.104.2.367 (1997).

Hattori, M. & Oaksford, M. Adaptive non-interventional heuristics for covariation detection in causal induction: model comparison and rational analysis. Cogn. Sci. 31, 765–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/03640210701530755 (2007).

Takahashi, T., Kohno, Y. & Oyo, K. Causal induction heuristics as proportion of Assumed-to-be Rare Instances (pARIs). In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Cognitive Science. ICCS, 361–362. (2010).

Takahashi, T., Oyo, K., Tamatsukuri, A. & Higuchi, K. Correlation detection with and without the theories of conditionals: A model update of Hattori and Oaksford In Logic and Uncertainty in the Human Mind. (Routledge, 2020).

Higuchi, K., Oyo, K. & Takahashi, T. Causal intuition in the indefinite world: Meta-analysis and simulations. Biosystems https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystems.2023.104842 (2023).

Marsh, J. K. & Ahn, W. K. Spontaneous assimilation of continuous values and Temporal information in causal induction. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 35, 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014929 (2009).

Anderson, J. R. The Adaptive Character of Thought (Erlbaum, 1990).

McKenzie, C. R. & Mikkelsen, L. A. A bayesian view of covariation assessment. Cogn. Psychol. 54, 33–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2006.04.004 (2007).

Guilford, J. P. Psychometric Methods (McGraw–Hill Book Company, (1936).

Jaccard, P. The distribution of the flora in the alpine zone. New. Phytol. 11, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1912.tb05611.x (1912).

Hubálek, Z. Coefficients of association and similarity, based on binary (presence-absence) data: an evaluation. Biol. Rev. 57, 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1982.tb00376.x (1982).

Taha, A. A. & Hanbury, A. Metrics for evaluating 3d medical image segmentation: analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med. Imaging. 15, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-015-0068-x (2015).

Tversky, A. Features of similarity. Psychol. Rev. 84, 327–352. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.4.327 (1977).

Ochiai, A. Zoogeographical studies on the soleoid fishes found in Japan and its neighbouring regions-ii. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 22, 526–530. https://doi.org/10.2331/suisan.22.526 (1957).

Zhelezniak, V., Savkov, A., Shen, A. & Hammerla, N. Correlation coefficients and semantic textual similarity. Proc. 2019 Conf. North. Am. Chapter Assoc. Comput. Linguist. Hum. Lang. Technol. 1 (Long and Short Papers) 951–962. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/N19-1100 (2019).

Finetti, B. D. & Angell, B. The logic of probability. Philos. Stud. 77, 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00996317 (1995).

Baratgin, J., Politzer, G., Over, D. E. & Takahashi, T. The psychology of uncertainty and three-valued truth tables. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01479 (2018).

McGee, V. Conditional probabilities and compounds of conditionals. Philos. Rev. 98, 485–541. https://doi.org/10.2307/2185116 (1989).

Kaufmann, S. Conditionals right and left: probabilities for the whole family. J. Philos. Log. 38, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10992-008-9088-0 (2009).

Gilio, A. & Sanfilippo, G. Conditional random quantities and compounds of conditionals. Stud. Log. Int. J. Symb. Log. 102, 709–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11225-013-9511-6 (2014).

Sanfilippo, G., Pfeifer, N., Over, D. E. & Gilio, A. Probabilistic inferences from conjoined to iterated conditionals. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 93, 103–118. (2018).

Klayman, J. & Ha, Y. W. Confirmation, disconfirmation, and information in hypothesis testing. Psychol. Rev. 94, 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.2.211 (1987).

Oaksford, M. & Chater, N. A Rational Analysis of the Selection Task as Optimal Data Selection. Psychol. Rev. 101, 608–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.608 (1994).

Navarro, D. J., Perfors, A. F. & Hypothesis Generation Sparse categories, and the positive test strategy. Psychol. Rev. 118, 120–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021110 (2011).

Hattori, M. & Nishida, Y. Why does The base rate appear to be ignored? The equiprobability hypothesis. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 16, 1065–1070. https://doi.org/10.3758/PBR.16.6.1065 (2009).

Hattori, M. A quantitative model of optimal data selection in Wason’s selection task. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A. 55, 1241–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724980244000053 (2002).

Pearl, J. & Causality Models, Reasoning and Inference (Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Waldmann, M., Cheng, P. W., Hagmayer, Y., Blaisdell, A. & & & Causal Learning in Rats and Humans: A Minimal Rational Model (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Lagnado, D. A. & Sloman, S. Learning Causal Structure. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society. (2002).

Fernbach, P. M. & Rehder, B. Cognitive shortcuts in causal inference. Argum. Comput. 4, 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/19462166.2012.682655 (2013).

Rehder, B. Independence and dependence in human causal reasoning. Cogn. Psychol. 72, 54–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2014.02.002 (2014).

Rothe, A., Deverett, B., Mayrhofer, R. & Kemp, C. Successful structure learning from observational data. Cognition 179, 266–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2018.06.003 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 23K28159 and 23K18497.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. and K.H. conceived the project, H.I. collected the cognitive experimental data, K.H. analysed the cognitive experimental data and performed the simulations, T.T. and T.S. supervised the work, and K.H. and T.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Higuchi, K., Shirakawa, T., Ichino, H. et al. A dependence detection heuristic in causal induction to handle nonbinary variables. Sci Rep 15, 11638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91051-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91051-7