Abstract

The current understanding and a standardized assessment or treatment guidelines for keloids are not fully established, highlighting the need for an objective method to gauge keloid severity and treatment outcomes. This study investigated the clinical utility of multimodal ultrasound, integrating Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) and Angio planewave ultrasensitive imaging (AP), to assess keloid severity and treatment responses in 58 keloids across 31 patients. Keloids were categorized into mild, moderate, and severe based on Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) scores. The results revealed significant differences in keloid thickness, elasticity parameters, and blood flow levels among severity groups, with the AP technique demonstrated superior sensitivity in detecting keloid microcirculation. Additionally, the study evaluated the therapeutic response to Strontium-90 Yttrium-90 isotope applicator treatment in 28 keloids, categorizing them into 13 good responders and 15 poor responders based on improvements observed in their VSS scores. Good responders demonstrated marked improvements post-treatment, including significant flattening of the keloids, decreased stiffness, and normalization of blood flow levels. In contrast, poor responders exhibited minimal changes in keloid thickness, stiffness, and blood flow signals following treatment. These findings underscore the effectiveness of multimodal ultrasound in evaluating treatment responses in keloid management. In conclusion, multimodal ultrasound, focusing on SWE and AP modalities, offers a promising tool for comprehensive assessment, with potential to enhance keloid evaluation and track treatment responses across varying therapeutic interventions, thereby facilitating optimized clinical management and guiding personalized treatment. The study was successfully registered on ClinicalTrials.gov on 12/09/2023, with the Identifier NCT06034587.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Keloids are benign fibrous skin tumors that result from aberrant wound healing responses, often characterized by excessive collagen deposition, increased vascularity, and elevated tissue tension. Their development unfolds through distinct pathological stages. Initially, inflammatory responses trigger substantial cellular infiltration and angiogenesis, followed by aberrant collagen synthesis driven by fibroblast proliferation, which increases the rigidity of the scar tissue. These processes ultimately lead to the formation of a mature keloid1,2,3. Despite various treatment modalities, including surgical excision, laser therapy, radiation therapy, and pharmacological interventions, there is no universal approach to prevent recurrence or effectively treat all keloids4,5,6. This challenge partly arises from an incomplete understanding of the mechanisms underlying keloid formation, leading to difficulties in treatment. While many patients experience some degree of improvement following initial treatment, a concerning issue remains—the high recurrence rate and refractoriness of keloids. Recurrent keloids often prove more stubborn than their initial appearance, exerting sustained negative effects on both the physical and psychological well-being of patients1. To address these issues, there is a need for accurate keloid severity assessment and the identification of therapy-responsive or therapy-resistant cases. Traditionally, clinicians have relied on subjective visual and tactile examinations, which can result in variability between evaluators, such as the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS)7. In addition, VSS and methods like dermoscopy and laser scanning technique without the ability to visualize subcutaneous part, which can only assess surface characteristics8,9,10. Moreover, many advanced evaluation techniques, such as three-dimensional imaging, optical coherence tomography(OCT) and laser doppler flowmetry, while informative, are often complex, time-consuming, and focused on specific aspects of keloid evaluation, such as color, texture, blood flow, and tension10,11,12,13. This specialization limits their clinical utility. Given these challenges, multimodal ultrasound, encompassing B-mode ultrasound, shear wave elastography (SWE), and angiography pulse (AP) imaging, emerges as a non-invasive, quantitative, and objective approach that overcomes these limitations. Angio planewave ultrasensitive imaging (AP) imaging is a specialized ultrasound technique employed to assess microvascular changes within tissues, offering detailed visualizations of blood flow patterns and microvessels. Unlike the traditional color Doppler ultrasound techniques, such as Color Doppler Flow Imaging (CDFI) and Power Doppler Imaging (PDI), AP imaging highlights the presence and distribution of blood microvessels, making it particularly valuable for evaluating the microvascular perfusion status of keloids and further assessing treatment efficacy through the quantification of dynamic microvascular parameters14,15.

SWE, a non-invasive ultrasound imaging modality that has gained recognition for its ability to measure tissue stiffness16. This technique generates shear waves and analyzes their propagation within viscoelastic tissue. The fundamental principle underlying SWE is that stiffer tissues propagate shear waves more rapidly than softer ones17. This technology has found applications in various skin diseases, including systemic sclerosis and localized scleroderma18,19. While previous studies have studied SWE’s effectiveness in quantitatively assessing keloid stiffness and identifying treatment effects20,21, its potential in assessing keloids has yet to be fully explored. This is the first study to explore the substantial potential of multimodal ultrasound for differentiating keloid severity and monitoring treatment responses within a single treatment strategy.

Methods

Study design and population

A prospective longitudinal observational clinical study was conducted at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from June 2021 to September 2022. Besides, ethical approval was achieved from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University Ethics Committee. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study included 31 outpatients (mean age 27.9 ± 8.5 years, 14 males, 17 females) with a total of 58 untreated keloids located in various anatomical areas. Among these patients, 28 keloids underwent isotope therapy to evaluate their treatment response. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Detailed medical records were collected, including demographic characteristics, clinical history, and keloid-related information, including etiology, duration, location, morphological changes, and associated symptoms. The keloids were distributed across several sites: chest (23), shoulder (13), abdomen (6), leg (6), neck (3), perineum (3), buttock (2), and hand (2). Participants included individuals with keloids needing treatment, however, those under the age of 16 and individuals with a history of prior keloid treatment were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria comprised pregnant or breastfeeding women, patients with malignant tumors, hypertension, diabetes, skin ruptures, skin infections, or other dermatological conditions that could affect keloid healing. For each enrolled keloid, a corresponding normal skin site or contralateral normal skin was selected as a control. Measurements were taken at two sites: one at the keloid and one at the normal skin site, ensuring a minimum distance of 3 cm from the edge of the keloid.

Clinical assessment

VSS is a widely recognized questionnaire used for keloid evaluation. This scale evaluates aspects of keloid, including vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, and height, with scoring system ranging from 0 to 15, where lower scores indicate less severity (0 being the least severe, and 15 the most severe). In our study, keloids were categorized into three groups based on their VSS scores: mild (0–5), moderate (6–9), and severe (10–15). The evaluation of VSS scores was conducted by a nuclear medicine doctor who was also responsible for conducting radioisotope applicator therapy.

Multimodal ultrasound assessment in keloids of varying severities

Multimodal ultrasound evaluations were performed on all 58 untreated keloids and corresponding areas of normal skin at baseline. Key assessment parameters included thickness measured by B-mode ultrasound, elasticity evaluated using Shear Wave Elastography (SWE), and vascularity assessed through Color Doppler Flow Imaging (CDFI), Power Doppler Imaging (PDI), and AP mode. An Aixplorer ultrasound machine (SuperSonic Imaging, Ltd, Aix-en-Provence, France), equipped with PDI, AP, and SWE functions, was used for all examinations employing a 4-15 MHz linear probe.

A coupling pad was applied to the keloid surface for clear ultrasound images. Thickness measurement was taken at the thickest part of keloid on B-mode ultrasound, with a corresponding measurement on normal skin serving as a control. Vascularity of both skin lesions and normal sides was directly evaluated using three color modes: CDFI, PDI, and AP. These modes were employed to compare the sensitivity of blood flow detection, with AP particularly useful for identifying minimal vascularity. Vascular scales were categorized into four levels according to Adler et al.‘s 1990 scale: Level 0 (absence of a blood flow signal), Level 1 (1–2 punctate or short rod blood signals), Level 2 (3–4 punctate blood signals or a longer vascular structure in the lesions with a length close to or greater than the radius), and Level 3 (five or more punctate blood signals or two longer blood vessels)22.

Elasticity was evaluated by the SWE mode, with a color scale in the top-right corner of the elastogram indicating elasticity fluctuations: red for hard tissue and blue for soft tissue. The visual display of the shear wave scale was set in a range from 0 kPa to 300 kPa. We selected the thickest area of the keloid as the region of interest (ROI) for elastography measurement, a choice supported by previous studies. These studies indicate that the elastic modulus of the hardest regions within scars, including keloids, reflects the activity of pathological scars more accurately than assessments of the entire scar region23. This approach allows for a more focused and accurate analysis of keloid stiffness. All elasticity parameters (EPs), including the mean, maximum, minimum values of shear wave velocity, and the mean, maximum Young’s modulus (C-mean, C-max, C-min, E-mean, E-max), were automatically displayed on the image. The elasticity parameters of the corresponding normal skin (EP-norm) were also obtained. To minimize variations associated with individual subjects, anatomical sites, and operator dependency, stiffness quantification was also performed using a standardized ratio, E-ratio (the five elasticity parameters of keloids/control normal skin)24. Considering that keloids belong to anisotropic tissues, which may exhibit different mechanical properties in various directions, we opted to use EPs obtained from longitudinal sections of ultrasound images for statistical analysis in this study.

High-quality sonogram, elastogram, and blood flow images were obtained by instructing the patient to breathe calmly and capturing images after the image had stabilized for 3–5 s. These images were acquired both pre-treatment, post-treatment and during follow-ups. All examinations were performed by a trained sonographer with 5 years of experience in ultrasound examination. The ultrasound measurements and the evaluation of the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) scores were conducted in a blinded manner.

Multimodal ultrasound assessment of keloid therapeutic response

To assess treatment outcomes, we divided the 28 treated keloids into two groups: 13 keloids classified as “good responders,” which demonstrated an improvement of 5 or more points in the VSS score, and 15 keloids classified as “poor responders,” showing less than a 5-point improvement in the VSS score25. To mitigate potential observational biases related to the treatment method, we employed a single treatment strategy, radioisotope applicator therapy with Strontium-90 Yttrium-90 isotope (90Sr-90Y, with the identifier 0094SR814975), provided by the China Atomic Energy Research Institute. The therapy instrument had dimensions of 2.8 cm x 2.8 cm and treated an area of 2.0 cm x 2.0 cm, delivering a radiation dose of 5.0 Gy/h. Each patient received superficial radiation therapy through a single 90Sr source in multiple 2 Gy doses over 5 sessions. The applicator was customized to match the keloid’s size, extending 0.5 cm beyond its edge and making direct contact with the keloid tissue surface.

To evaluate the treatment response using multimodal ultrasound, we conducted a follow-up assessment 6 months post-treatment, employing the same evaluation methods as at baseline and comparing the parameters from pre- and post-treatment assessments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). To assess keloid severity, we used the Mann-Whitney U test to compare various indicators among the three groups, including thickness, stiffness, E-ratio, and blood flow. We applied the Mann-Whitney U test for ordered variables to evaluate differences in blood flow grades using three Doppler sonography techniques in untreated and treated patients. To assess treatment response, we used the same approach to compare blood flow grades, keloid thickness, and stiffness indicators in good and poor responders before and after treatment. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

The study encompassed 58 keloids in 31 patients (15 males and 16 females), aged between 19 and 67 years (mean age 39 years, ±SD 13.67). Keloids were located on various anatomical sites, including the chest (n = 23), shoulder (n = 13), abdomen (n = 6), leg (n = 6), neck (n = 3), perineum (n = 3), buttock (n = 2), arm (n = 2), and hand (n = 2).

Results of multimodal ultrasound in keloids of varying severities

According to the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), we categorized 20 keloids (34.4%) as mild (VSS 0–5), 26 keloids (44.8%) as moderate (VSS 6–10), and 12 keloids (20.6%) as severe (VSS 11–15), with VSS scores ranging from 1 to 13 points (mean 7.23 points). In contrast, normal skin scores ranged from 0 to 2 points (mean 0.68 points). Our study aimed to assess the ability of multimodal ultrasound to differentiate between keloids of varying severities and presented clinical and multi-ultrasound images of keloids at different severity levels (Fig. 1).

(a–c) Clinical images of mild, moderate, and severe keloids, respectively (black circles indicate keloid locations). (d–f) HFUS images showing keloid thickness: 2.23 mm (mild), 3.87 mm (moderate), and 5.04 mm (severe). (g-i) AP images illustrating blood flow patterns: minimal in mild, sparse in moderate, and abundant in severe keloids. (j–l) Elastography images depicting tissue stiffness: extremely soft (mild), intermediate (moderate), and extremely hard (severe). HFUS high-frequency ultrasound, AP Angio planewave ultrasensitive imaging.

The multimodal ultrasonic data for different severity groups are depicted in Fig. 2; Table 1. Thickness measurements obtained using B-mode ultrasound demonstrated significant differences among mild, moderate, and severe cases (P = 0.02), consistent with the severity of keloid formation (Figs. 1d-f and 2d). The average thickness was 3.0 mm (± SD 0.5) for mild keloids, 4.4 mm (± SD 0.4) for moderate keloids, and 4.6 mm (± SD 0.4) for severe keloids. Figure 2a-c demonstrate that all Elasticity Parameters (EPs) and the E-ratio, measured using Shear Wave Elastography (SWE), show severity-dependent trends. As the severity of keloids increases, the EPs and E-ratio consistently rise, indicating a statistically significant positive correlation with keloid severity (P < 0.001) across the mild, moderate, and severe keloid groups.

Multimodal ultrasound measurements across different keloid severities include (a) Young’s modulus (E-mean, E-max) from SWE, (b) shear wave velocity (C-mean, C-max, C-min) from SWE, (c) E-ratio, calculated as the elasticity ratio between keloid and adjacent normal skin, and (d) thickness measured via HFUS. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test for multiple independent samples; ***p < 0.001, with all group comparisons showing significant differences. SWE Shear Wave Elastography.

Furthermore, blood flow levels assessed in the AP mode displayed significant variations, as shown in Fig. 1g-i. The AP mode could differentiate between the mild-moderate and mild-severe groups (P = 0.045 and P = 0.05, respectively). Mild keloids showed almost no vessels, while severe keloids exhibited abundant blood flow signals with a high vessel presence. Whereas the CDFI and PDI modes only distinguished the mild-moderate group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.004, respectively). All the blood flow gradings are shown in Table 1. In addition, the evaluation of vascularity within keloids using three different color flow modes yielded significant findings. The AP mode detected blood flow signals that exhibited statistically significant differences between untreated and treated patients (P < 0.001, as shown in Table 2). Figure 3 visually illustrates this observation, demonstrating that as the blood flow grade increases, the quantity and richness of blood flow signals correspondingly increase. However, the blood flow grading detected by CDFI and PDI modes did not show significant differences. This highlights the sensitivity of the AP mode in detecting changes in microvascular blood flow, providing valuable insights into the evolving status and activity of keloids.

Therapeutic response of keloids traced by multimodal ultrasound

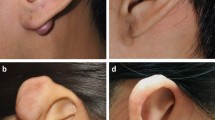

After treating 28 keloids with the radioactive isotope 90Sr-90Y, we categorized them into two groups: good-responders and poor-responders. There were no reported adverse effects during the treatment sessions. We analyzed various ultrasound parameters before and after treatment for both groups to track their response to the treatment. Figure 4 shows representative clinical pictures of keloid with two sets of different treatment response before and after treatment, Fig. 4a depicts the state of the keloid in Case 1 before treatment, while Fig. 4b shows significant improvement post-treatment, indicating a positive response to the therapy. In contrast, Fig. 4c, d display the pre- and post-treatment condition of Case 2. Despite undergoing the same treatment, this patient exhibited minimal improvement, indicating a poorer response to the therapy. Specifically, in the good-responder group, elasticity parameters, including C-mean, C-max, C-min, E-mean, and E-max, exhibited a significant reduction (all P < 0.001), as did the E-ratio parameters. The P-values for C-mean-ratio, C-max-ratio, and C-min-ratio were all 0.003, while the P-values for E-mean and E-max were 0.006 and 0.013, respectively. The AP mode exhibited significant differences in vascular signal levels between the pre-treatment and post-treatment stages (P < 0.001), whereas both CDFI and PDI showed no significant differences (with P values of 0.134 for both). Although keloid thickness significantly decreased in both the good-responder and poor-responder groups after treatment (P < 0.001 and P = 0.041), there were no significant changes in elasticity parameters (P > 0.05) or color flow sonography modes (AP, PDI, and CDFI) when comparing pre-treatment and post-treatment stages (P = 0.170, P = 0.290, P = 0.827, respectively).

Discussion

Microcirculation is closely associated with keloid symptoms, such as pain, itching, and warmth. Abnormal microcirculation within keloids can exacerbate these symptoms. Factors like vascular density, microcirculation velocity, and blood flow distribution may significantly impact keloid growth and repair processes26,27,28. Therefore, assessing microvascular changes and low-velocity vessels within keloids is crucial, as they are associated with clinical activity, inflammation, angiogenesis, tissue repair, and regeneration27,29. Our study employed three different color flow modes: AP, CDFI, and PDI. Both CDFI and PDI demonstrated limited ability to distinguish between keloid severities, which is consistent with previous research using CDFI to assess keloid blood flow. These studies also reported a weak correlation between the blood flow detected by CDFI and the severity of keloids20. In our study, we observed that CDFI and PDI could only effectively differentiate the mild-moderate group among keloid severities. In contrast, the AP mode effectively distinguished between mild-moderate and mild-severe keloids, showcasing a positive correlation between blood flow and severity. This is consistent with the known relationship between increased local blood flow and inflammatory responses in keloids, making AP mode an early indicator of keloid activity30. Active keloids exhibit higher blood flow and inflammatory responses compared to their quiescent counterparts31,32. Recognizing these differences in blood flow has significant implications for treatment planning. For keloids displaying heightened blood flow, clinicians may consider specialized therapies targeting angiogenesis, such as angiogenesis inhibitors or anti-angiogenic drugs33,34,35. Conversely, certain therapies, like cryotherapy and laser treatment, can influence angiogenesis in keloid tissue by targeting blood vessels to reduce blood flow within keloid nodules36. Interestingly, our study found that the microvascular grading detected by the AP mode significantly decreased in good responders after treatment compared to pre-treatment. This reduction in blood flow may indicate decreased inflammation and a positive treatment response, suggesting a gradual normalization of blood flow with successful treatment. Conversely, poor responders did not show significant changes in blood flow parameters post-treatment. This may indicate that the treatment is unsuitable or requires adjustment, prompting clinicians to consider alternative or more intensive strategies to optimize outcomes. Additionally, the absence of notable changes in microvascular parameters may suggest that the keloid has stabilized or might not see substantial improvement. Therefore, AP provides real-time monitoring of microvascular changes, which is essential for understanding the inflammatory activity associated with keloids. This information is crucial for weighing the pros and cons of continued treatment and engaging in shared decision-making with the patient to determine whether to proceed with the current approach or explore alternatives.

Previous research has established the reliability and reproducibility of Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) in quantifying tissue stiffness within keloids20,23. In our study, SWE exhibited similar performance to previous studies, with elasticity parameters showing severity-dependent trends. Higher severity keloids consistently exhibited elevated values, indicating increased tissue stiffness, aligning with the well-established understanding of keloids characterized by excessive collagen accumulation, affecting tissue elasticity37. A decrease in Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) scores corresponded to a decrease in the elastic modulus, signifying keloid softening. Song-Ya Huang’s research has also demonstrated the potential of Shear Wave Elastography (SWE) in distinguishing keloids from normal skin and assessing treatment efficacy, although these studies were conducted without specific groupings and involved different treatment modalities21. In contrast, our study highlights the dynamic nature of tissue stiffness, enabling us to track changes over time and gain valuable insights into treatment responses through a single strategy. This capability enables clinicians to make timely adjustments to treatment strategies, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of keloid management. Figures 5, 6, 7 and 8 effectively illustrate SWE’s capability to differentiate between good-responsive and poor-responsive keloids. Notably, stiffness parameters significantly decreased in keloids with a favorable therapeutic response, while remaining unchanged in the poor-responsive group. This implies that patients with softer keloids may respond positively to radioisotope application therapy, whereas those with stiffer keloids may necessitate alternative approaches. A continued decrease in stiffness may indicate an ongoing positive response to treatment, but it may also signify a risk of recurrence or insensitivity to the chosen treatment strategy. Ishiko T et al.38 has reported a deficiency in elastic fibers within the extracellular matrix of keloids. Successful treatment, as indicated by their findings, may contribute to the restoration of elastic fiber and collagen fibril levels, potentially aligning with our observations. Additionally, it is imperative to consider the inherent characteristics of the tissue assessed using SWE. Biological tissues, including keloid scars, typically exhibit heterogeneity, anisotropy, and the potential for non-linear elastic behavior39. To address this issue, we introduced a new indicator: the ratio of keloid elasticity from different body regions to their corresponding normal skin. Furthermore, the location of the lesion significantly influences treatment outcomes, with studies showing more favorable results in labial and abdominal lesions, while those on the anterior chest wall and upper arm exhibit limited responsiveness40. Our findings, reflected in the ratio of EP-EPnorm, align with other elasticity parameters. Thus, a ratio-based algorithm for elasticity assessment can enhance the reliability of SWE assessments and strengthen measurement robustness.

Multimodal ultrasound images of a good responder (case 1) before and after treatment. (a) HFUS shows a pre-treatment thickness of 1.55 mm, indicating keloid presence. (b) SWE indicates the keloid is hard, while (c) AP reveals high vascularity with abundant blood flow signals. Post-treatment, (d) HFUS indicates significant flattening, (e) SWE shows the keloid is soft, and (f) AP displays near-normal blood flow signals, reflecting reduced vascularity.

Multimodal ultrasound images of a poor responder (case 2) obtained from HFUS, SWE, and AP. (a) HFUS image before treatment shows a thickness of 3.26 mm. (b) SWE analysis indicates the keloid is hard, reflecting its stiffness. (c) AP image before treatment reveals sparse dot-like and linear blood flow signals, suggesting limited vascularity. After treatment, (d) HFUS shows thickness remains at 3.15 mm, indicating negligible change. (e) SWE analysis post-treatment indicates minimal alterations in keloid stiffness. (f) AP image after treatment demonstrates persistent sparse punctate blood flow signals.

Comparison of multimodal ultrasound evaluation data for the good responder group before and after treatment. (a) Young’s modulus values (E-mean and E-max) from SWE, (b) shear wave velocity (C-mean, C-max, C-min) from SWE, (c) thickness measured by HFUS, (d) blood flow grading via AP mode, (e) blood flow grading via PDI mode, (f) blood flow grading via CDFI mode. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test; ***p < 0.001.

Comparison of multimodal ultrasound evaluation data for the poor responder group before and after treatment. (a) Young’s modulus values (E-mean and E-max) from SWE, (b) shear wave velocity (C-mean, C-max, and C-min) from SWE, (c) thickness measured by HFUS, (d) blood flow grading via AP mode, (e) blood flow grading via PDI mode, (f) blood flow grading via CDFI mode.

Additionally, as observed in our study, keloid thickness increased significantly with the severity of keloid formation, aligning with the findings of Guo et al.20. This is also consistent with the well-established understanding that keloids are characterized by the excessive accumulation of collagen fibers, resulting in elevated tissue thickness37. Quantifying keloid thickness using HFUS emerged as a robust indicator for keloid assessment. Ultrasound and 3D topographic imaging devices have also served as objective tools to evaluate the efficacy of combined cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroid injections for keloid treatment, revealing significant reductions in scar volume and height post-treatment41. Our study indicates that while keloid thickness significantly decreases after treatment in both good-responder and poor-responder groups, the lack of corresponding reductions in stiffness and microvascular grading in poor responders raises concerns. Changes in tissue properties, particularly stiffness, often precede visible improvements in ultrasound, similar to patterns seen in liver fibrosis and musculoskeletal diseases. Therefore, SWE and AP could play a key role in tailoring effective treatment strategies. If keloids show improved thickness without a decrease in stiffness and microvascular parameters, they should be classified as poor-responders or non-responders. This distinction is especially crucial for high-risk groups, such as patients with a history of recurrence, as it suggests a need for alternative treatment modalities or intensified approaches.

Hence, the integration of a one-stop examination combining three different ultrasound modalities (B-US, AP-US, and SWE) has the potential to enhance keloid detection, visualize the healing process, and monitor treatment response. These modalities, integrating both structural and functional information, offer quantitative parameters that could contribute to establishing widely accepted evaluation standards. However, a notable limitation of our study is the lack of established thresholds, particularly for AP and SWE. Additionally, we also acknowledge inherent limitations, such as operator variability and the heterogeneous nature of scar tissue. Future research should explore and combine more quantitative methods, such as superb microvascular imaging (SMI) and photoacoustic imaging, which can provide detailed metrics on blood flow distribution and oxygenation status, thereby enhancing our understanding of microcirculation and inflammatory activity in keloids. To further solidify the utility of multimodal ultrasound in keloid assessment and treatment monitoring, future studies should consider expanding patient cohorts, extending follow-up periods, and incorporating a wider range of treatment modalities to gain a more comprehensive understanding the effectiveness of these techniques.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our integrated approach combines three ultrasound modalities-B-mode Ultrasound (B-US), Angio planewave ultrasensitive imaging (AP), and Shear Wave Elastography (SWE)-into a one-stop examination, supplemented by clinical assessment scales. This method provides clinicians with a comprehensive and objective framework for keloid evaluation. B-US delivers detailed imaging of keloid structure and thickness, AP monitors microvascular changes critical for understanding inflammation and treatment responses, while SWE quantifies tissue stiffness to assess severity and predict outcomes. By integrating these modalities, our approach improves treatment monitoring, facilitates early identification of poor responders and supports research into novel treatment options, ultimately promoting personalized and optimized management strategies for each patient.

Data availability

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Grabowski, G., Pacana, M. J. & Chen, E. Keloid and hypertrophic Scar formation, prevention, and management: standard review of abnormal scarring in orthopaedic surgery. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 28(10), e408–e414 (2020).

Limandjaja, G. C., Niessen, F. B., Scheper, R. J. & Gibbs, S. The keloid disorder: heterogeneity, histopathology, mechanisms and models. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 8, 360 (2020).

Harn, H. I. et al. The tension biology of wound healing. Exp. Dermatol. 28(4), 464–471 (2019).

Ogawa, R., Dohi, T., Tosa, M., Aoki, M. & Akaishi, S. The latest strategy for keloid and hypertrophic Scar prevention and treatment: the Nippon medical school (NMS) protocol. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 88(1), 2–9 (2021).

Ogawa, R. The most current algorithms for the treatment and prevention of hypertrophic scars and keloids: A 2020 update of the algorithms published 10 years ago. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 149(1), 79e–94e (2022).

Dong, W., Qiu, B. & Fan, F. Adjuvant radiotherapy for keloids. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 46(1), 489–499 (2022).

Lipman, K. et al. Evaluating current Scar assessment methods. Ann. Plast. Surg. 84(2), 222–231 (2020).

Yoo, M. G. & Kim, I. H. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: characteristic vascular structures visualized by using dermoscopy. Ann. Dermatol. 26(5), 603–609 (2014).

Limbourg, A., Radtke, C., Ipaktchi, R. & Vogt, P. M. [Analysis of critically perfused tissues by laser speckle contrast analysis (LASCA) perfusion imaging]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast. Chir. 48(6), 354–362 (2016).

van der Aa, T. et al. A simplified three-dimensional volume measurement technique in keloid scars: validity and reliability. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 68(11), 1574–1580 (2015).

Ud-Din, S. & Bayat, A. Noninvasive objective tools for quantitative assessment of skin scarring. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle). 11(3), 132–149 (2022).

Ud-Din, S. & Bayat, A. Non-invasive objective devices for monitoring the inflammatory, proliferative and remodeling phases of cutaneous wound healing and skin scarring. Exp. Dermatol. 25(8), 579–585 (2016).

Markus, R. et al. Objective and subjective treatment evaluation of scars using optical coherence tomography, sonography, photography, and standardized questionnaires. Eur. J. Dermatol. 26(6), 599–608 (2016).

Aixplorer White Paper, Supersonic Imaging, Angio PL.U.S Ultrasound Imaging. https://www.supersonicimagine.com/Aixplorer-MACH2/TECHNOLOGY, 9.17.

Liu, H. et al. A new tool for diagnosing parathyroid lesions: angio plus ultrasound imaging. J. Thorac. Dis. 11(11), 4829–4834 (2019).

Săftoiu, A. et al. The EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations for the clinical practice of elastography in Non-Hepatic applications: update 2018. Ultraschall Med. 40(4), 425–453 (2019).

Shiina, T. et al. WFUMB guidelines and recommendations for clinical use of ultrasound elastography: part 1: basic principles and terminology. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 41(5), 1126–1147 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. Quantitative assessment of skin stiffness using ultrasound shear wave elastography in systemic sclerosis. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 45(4), 902–912 (2019).

Wang, L., Yan, F., Yang, Y., Xiang, X. & Qiu, L. Quantitative assessment of skin stiffness in localized scleroderma using ultrasound Shear-Wave elastography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 43(7), 1339–1347 (2017).

Guo, R. et al. Quantitative assessment of keloids using ultrasound shear wave elastography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 46(5), 1169–1178 (2020).

Huang, S. Y. et al. Quantitative assessment of treatment efficacy in keloids using high-frequency ultrasound and shear wave elastography: a preliminary study. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 1375 (2020).

Adler, D. D., Carson, P. L., Rubin, J. M. & Quinn-Reid, D. Doppler ultrasound color flow imaging in the study of breast cancer: preliminary findings. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 16(6), 553–559 (1990).

Hang, J. et al. Correlation between elastic modulus and clinical severity of pathological scars: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 23324 (2021).

DeJong, H. et al. Objective quantification of burn Scar stiffness using shear-wave elastography: initial evidence of validity. Burns 46(8), 1787–1798 (2020).

Yin, Q. et al. Intralesional corticosteroid administration in the treatment of keloids: A scoping review on injection methods. Dermatology 239(3), 462–477 (2023).

Zheng, J., Song, F., Lu, S. L. & Wang, X. Q. Dynamic hypoxia in Scar tissue during human hypertrophic Scar progression. Dermatol. Surg. 40(5), 511–518 (2014).

Kurokawa, N., Ueda, K. & Tsuji, M. Study of microvascular structure in keloid and hypertrophic scars: density of microvessels and the efficacy of three-dimensional vascular imaging. J. Plast. Surg. Hand Surg. 44(6), 272–277 (2010).

Amadeu, T. et al. Vascularization pattern in hypertrophic scars and keloids: a Stereological analysis. Pathol. Res. Pract. 199(7), 469–473 (2003).

Chen, C. et al. Activity of keloids evaluated by multimodal photoacoustic/ultrasonic imaging system. Photoacoustics 24, 100302 (2021).

Ogawa, R. Keloid and hypertrophic scars are the result of chronic inflammation in the reticular dermis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18(3), 606 (2017).

Elrefaie, A. M., Salem, R. M. & Faheem, M. H. High-resolution ultrasound for keloids and hypertrophic Scar assessment. Lasers Med. Sci. 35(2), 379–385 (2020).

Bessonart, M. N., Macedo, N. & Carmona, C. High resolution B-scan ultrasound of hypertrophic scars. Skin. Res. Technol. 11(3), 185–188 (2005).

Dong, L. & Fang, Y. [Advances in the research of treatment of angiogenesis inhibitor on pathological scars]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 33(10), 653–656 (2017).

Arbiser, J. L. Angiogenesis and the skin: a primer. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 34(3), 486–497 (1996).

Ammendola, M. et al. Tryptase-positive mast cells and angiogenesis in keloids: a new possible post-surgical target for prevention. Updates Surg. 65(1), 53–57 (2013).

Naik, P. P. Novel targets and therapies for keloid. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 47(3), 507–515 (2022).

Cohen, B. E., Geronemus, R. G., McDaniel, D. H. & Brauer, J. A. The role of elastic fibers in Scar formation and treatment. Dermatol. Surg. 43(Suppl 1), S19–S24 (2017).

Ishiko, T. et al. Chondroitinase injection improves keloid pathology by reorganizing the extracellular matrix with regenerated elastic fibers. J. Dermatol. 40(5), 380–383 (2013).

Tsai, W. Y., Hsueh, Y. Y., Chen, P. Y., Hung, K. S. & Huang, C. C. High-Frequency ultrasound elastography for assessing elastic properties of skin and scars. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 69(6), 1871–1880 (2022).

Al-Attar, A., Mess, S., Thomassen, J. M., Kauffman, C. L. & Davison, S. P. Keloid pathogenesis and treatment. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 117(1), 286–300 (2006).

Schwaiger, H., Reinholz, M., Poetschke, J., Ruzicka, T. & Gauglitz, G. Evaluating the therapeutic success of keloids treated with cryotherapy and intralesional corticosteroids using noninvasive objective measures. Dermatol. Surg. 44(5), 635–644 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172092).

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z., M.H.R.: Study concept and design; L.Z., C.X.Z., M.H.R.: Data acquisition; L.Z., M.H.R.: Data analysis; L.Z., M.H.R., Z.G.W.: Manuscript preparation; L.Z., Q.Z.: Statistical analysis; L.Z., M.H.R., Z.G.W.: Manuscript editing; All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of it. Statement: All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Zhou, Q., Zheng, C. et al. Multimodal ultrasound assessment for monitoring keloid severity and treatment response. Sci Rep 15, 8568 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91111-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91111-y

This article is cited by

-

Update on newer ultrasound systems to study the microvasculature

La radiologia medica (2025)