Abstract

The microstrip patch antenna exhibits frequency stability under temperature variations, making it suitable for applications in the Industrial Internet, resource extraction, structural health monitoring, and other fields. A low-profile complementary split ring resonator (CSRR) structure is introduced into the radiating patch of the antenna, confining the electric field energy within a small region inside the ring. This design significantly enhances the antenna’s sensitivity to changes in the dielectric constant. The synergy between the patch antenna and the CSRR structure forms an efficient dual-resonance system. Operating in a dual-band mode increases spectral efficiency and adapts to multi-band communication networks. To develop a sensor for real-time temperature detection, we explored various feeding methods for the antenna and optimized the structural parameters of its components. During this process, we found that adjusting the length, width, and opening size of the CSRR can achieve controllable tuning of the sensor’s operating frequency bands. We selected 99% pure alumina ceramic as the substrate material and utilized screen printing and high-temperature sintering techniques to solidify the heat-resistant silver paste into metallic patterns and ground planes. Experimental results show that the fabricated dual-band microstrip patch antenna sensor exhibits resonant frequencies of fr1 = 2.50 GHz and fr2 = 3.24 GHz at room temperature, consistent with simulation outcomes. As the temperature rises from 25 °C to 350 °C, the S11 curve shifts linearly to the left. The sensor achieves a notch depth of -42 dB, a quality factor of 1413, and a maximum sensitivity of 183 kHz/°C. It also demonstrates excellent performance in stability and repeatability tests, with both resonance points accurately characterizing temperature parameters. The designed dual-band microstrip patch antenna sensor offers superior performance, meeting the requirements for multi-band temperature testing in practical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temperature is one of the key indicators for measuring production processes, environmental. monitoring, and structural health status. Microwaves have excellent penetration capabilities, and the sensor technology in this frequency band is mature and has relatively low development costs1. More importantly, these sensors can cover a wide range of temperature sensing applications, from high temperatures to body temperatures and down to low temperatures2,3,4.

Planar microwave sensors based on the dielectric perturbation mechanism typically adopt a dual-port or tri-port structure. If they are to be used for high-temperature testing, it cannot be guaranteed that all connectors and solder joints will extend into the cold-end environment. Therefore, the application of these devices is currently limited to room temperature conditions5,6. The integration of temperature sensors with microstrip patch antennas has garnered increasing attention7,8,9. Sensors and antennas can be developed together and integrated on the same substrate according to application goals. These solutions do not require an additional transmission antenna for communication nor alignment operations between the antenna and the sensor10, providing an extremely attractive solution for achieving multiple functions within the same device.

Microstrip patch antennas demonstrate exceptional sensing capabilities based on the radiation variations (including frequency shifts, amplitude evolution, and Q–factor changes) induced by temperature changes11,12,13. As demonstrated in5, a single antenna simultaneously senses both temperature and strain. In fact, temperature sensing within the range of 33–77 °C is achieved on a single–band. In14, three types of microstrip patch antenna sensors—single–band, dual–band, and quad–band—are proposed by etching different numbers of resonators on the radiating patch. It is noted that mutual coupling occurs between multiple resonators, and the sensors’ operation at lower frequencies may lead to reduced sensitivity. Literature15 introduces a double H–shaped slot microstrip patch antenna stacked into a 4 × 4 array structure. This antenna can stably sense temperature in environments ranging from − 50 °C to 150 °C, with up to 11 resonant peaks on its response curve. However, the narrow frequency spacing between these resonant peaks poses a significant limitation, preventing broader temperature range testing due to potential crossover or overlap of resonant curves. The microstrip patch antenna sensing technology boasts a unique multifrequency temperature measurement capability. The sensor not only enhances spectral efficiency but also offers excellent performance, multi-band operation capability, high flexibility, and cost-effectiveness, demonstrating significant value in high-temperature monitoring within microwave frequency bands16. Moreover, in the field of the industrial Internet, monitoring production environments and specialized equipment requires deploying a large number of sensors. Considering the congested use of frequency bands, single-band measurement may not be able to meet the concurrent usage requirements of various sensors. Multiband microstrip antenna sensors can adapt to multiband communication networks, enabling signal transmission from one endpoint to multiple endpoints, significantly saving on costs and space while reducing the occurrence of frequency band conflicts within sensor networks6. Naturally, utilizing dual-band detection capabilities can reduce measurement errors and enhance measurement accuracy10.

It has been found that by incorporating geometric–shape slots, split ring resonator (SRR) particles, complementary split ring resonator (CSRR) particles, and interdigital structures into microstrip patch antennas, the characteristics of miniaturization, high gain, and large bandwidth can be achieved17,18,19,20. Among them, the CSRR was proposed by F. Falcone21 and others based on dipole theory. It has been verified as a novel metamaterial resonator22,23. At the resonant frequency of CSRR, the electric field energy is highly concentrated in the immediate vicinity of the resonant ring24. At this point, CSRR is particularly sensitive to changes in permittivity, providing a narrow insertion loss bandwidth and superior resonance sharpness25. In recent years, microstrip patch antenna sensors integrated with CSRR resonators have been widely used in fields including material characterization19,26, quality control27,28, and biomedicine29,30, and many more. The reason lies in the simple structure, low cost, and ease of processing of these sensors, allowing for large–scale production. Undoubtedly, the same mechanism can also be used for temperature monitoring. The CSRR structure and the patch antenna work together to present two resonant peaks in the output curve26. Taking the changes in resonant frequency, notch depth, and quality factor caused by temperature variations as detection variables, a sensing model is then constructed.

In this paper, three different schemes are considered, and after optimization, a dual–band, high Q–factor, and high sensitivity microstrip patch antenna temperature sensor is obtained. This sensor aims to support multi–band communication environments, thereby effectively addressing compatibility issues in communication networks. The etched CSRR structure is chosen to achieve dual–frequency operation while ensuring a compact design. The sensor is fabricated using ceramic processing, screen printing, and high–temperature sintering process, ultimately forming a dense silver film on the top and bottom surfaces of the ceramic substrate. The prepared sensor is mounted on test platform, and its dual–frequency temperature monitoring capabilities are characterized within the range of 25–350 °C.

Design

Temperature sensing mechanism

To obtain the monitoring information from the sensor when the temperature changes, a vector network analyzer (VNA) is first required to generate an interrogation signal containing the resonant frequency of the sensor, which is then transmitted to the sensor via a coaxial cable. When the frequency of the interrogation signal matches the inherent resonant frequency of the sensor, oscillation and attenuation occur within the resonant cavity at that frequency. However, the remaining signals are transmitted back to the VNA in the form of echo signals through the coaxial cable. When the temperature to be measured changes, the effective dielectric constant of the sensor is affected. At this time, the conductive metals on the top and bottom surfaces of the dielectric substrate jointly form an electromagnetic resonant cavity that radiates at a specific resonant frequency, thereby generating the first resonant peak on the S11 curve of the temperature sensor. Simultaneously, the CSRR structure etched on the top metal layer forms another resonant system, generating a second resonant peak on the return loss curve. At the resonant frequency of the sensor, the energies stored in the electric and magnetic fields are equal to each other. When dielectric perturbations are induced by changes in the temperature of the test environment, the electric and magnetic fields adjust mutually and generate new resonances. By establishing a relationship between frequency changes and temperature changes, temperature sensing can be achieved.

Based on the derivation of Maxwell’s equations, the electromagnetic field is interrelated with parameters such as the dielectric constant, which can be used to explain the working principle of microwave antenna sensors. When the measured temperature changes, the effective dielectric constant of the sensor will change accordingly, leading to a shift in the resonant frequency of the temperature sensor. The following presents the resonant frequency shift of the antenna temperature sensor caused by dielectric perturbations31:

where E0 and H0 represent the original electric and magnetic fields, while E1 and H1 are the electric and magnetic fields after perturbation due to temperature change. Δε and Δµ are the changes in the dielectric constant and magnetic permeability, respectively, V is the perturbed volume, and Δfr is the frequency shift of the resonant frequency fr with temperature. For this antenna sensor, the primary change before and after perturbation is in the dielectric constant Δε, while the magnetic permeability remains constant. Therefore, the formula can be further simplified as:

According to32, the effective dielectric constant ε is related to the dielectric constant εr of the substrate, the thickness H, and the electrical width ωe of the patch:

Based on prior research33, the relationship between the permittivity and temperature for alumina ceramics substrate can be modeled as a quadratic function. Consequently, the permittivity related to temperature can be expressed through the following equation:

where a and b are the fitted second– and first–order positive temperature coefficients, respectively, with a = 9.708 × 10–8 and b = 1.506 × 10–5. As the test temperature T increases, the εr(T) for the antenna sensor’s dielectric substrate rises substantially.

Therefore, in the simulation model, the temperature response of the sensor can be roughly determined by changes in εr. The 3dB–bandwidth (BW3dB) is a standard metric for peak accuracy, used to represent the performance parameter of the antenna used to represent the performance parameter of the antenna sensor. Consequently, the Q–factor is defined3:

where fr represents the resonant frequency, and BW3dB indicates the frequency difference between the two frequency points at 3dB above the resonant frequency. When simulating the sensor, a larger Q–factor can be achieved by adjusting the structural parameters.

The sensitivity S of the sensor is expressed as the ratio of the frequency shift Δfr to the temperature change ΔT, with the calculation formula given below34:

Structure of the designed antenna sensor

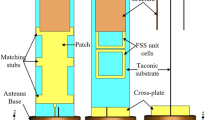

The 3D–structure and profile diagram of the proposed antenna sensor with the dimensions of (40 × 40 × 1 mm3) is presented in Fig. 1. The sensor exhibits a sandwich structure, consisting of a radiating patch, a dielectric substrate, and a ground plane, arranged from top to bottom. Among these, a CSRR resonant structure is introduced on the radiating patch, achieving a low-profile and compact design. The 99% alumina ceramic is selected as the substrate material, which features a high dielectric constant of 9.8 at room temperature. Compared to traditional antenna substrate materials such as FR4 and Rogers 588035, alumina’s high dielectric constant not only reduces the sensor size but also offers advantages in high radiation efficiency and ease of excitation, making it particularly suitable for microwave frequency applications16. The radiating patch and ground layer are fabricated using highly conductive silver, with a thickness set at 25 μm, ensuring superior electromagnetic performance. The feedline width is set to 2.5 mm (Ws), providing a characteristic impedance of 50Ω, which ensures the accuracy and reliability of simulation results.

Design and optimization of antenna sensor

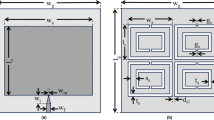

Figure 2a–c illustrate the geometric configurations of a rectangular microstrip patch antenna, a bridge–shaped defect microstrip patch antenna sensor (BD–MAS), and a bridge– and CSRR–shaped defect microstrip patch antenna sensor (BCD–MAS). For a better comparison of the sensing performances among these three devices, all other components are identical except for the radiation patches and feeding structures. The above components were simulated using high frequency structural simulator (HFSS) 2021.

(a–c) Rectangle microstrip patch antenna; bridge-shaped defect microstrip patch antenna sensor (BD–MAS); bridge– and CSRR–shaped defect microstrip patch antenna sensor (BCD–MAS). (d–f) S11 curves corresponding to the models in plots a–c. (g–i) Distribution of the electric field at the resonant frequency corresponding to the model in plots a–c.

As can be seen from the response curve in Fig. 2d, the rectangular microstrip patch antenna resonates near 2.63 GHz, where the S11 value reaches its minimum, approximately − 1.01dB. The primary reason for the exceptionally small notch depth is that the characteristic impedance of traditional rectangular microstrip antennas is not 50Ω. Such low–resolution signals cannot meet practical engineering requirements. Moreover, when the dielectric constant of the substrate changes, the resonant frequency does not shift regularly, indicating that this antenna cannot be used as a temperature sensor. Subsequently, impedance matching is performed on the rectangular microstrip patch antenna, and a bridge–shaped slot is opened at the connection position between the feedline and the antenna. The simulation result, as shown in Fig. 2e, indicates that an effective resonance point is formed on the output curve of BD–MAS, with a significantly increased quality factor, and the resonance amplitude decreases from − 1.01dB to − 20.75dB. When the dielectric constant of the ceramic substrate increases from 9.8 to 11.9, the resonance curve of the sensor shifts linearly to the left by 0.276 GHz, making it suitable for temperature monitoring. To further increase the number of operating frequency bands for the sensor, a metamaterial defect is added to BD–MAS. At this point, both the patch antenna and the CSRR structure are used together as resonant systems for temperature sensing, as shown in Fig. 2f. It can be observed that when the dielectric constant of the substrate changes from 9.8 to 11.9, the S11 curve experiences a frequency shift of 0.28 GHz at fr1 = 3.24 GHz and 0.44 GHz at fr2 = 4.88 GHz, both of which are significantly better than the shift observed in BD–MAS. These conclusions can be further corroborated by the electric field distributions depicted in Fig. 2g–i. Specifically, at the resonant frequency, the electric field of the rectangular microstrip patch antenna and BD–MAS primarily concentrates at the top corners of the upper half of the radiation patch and along both sides of the feedline. In contrast, BCD–MAS exhibits concentrated electric fields not only at these locations but also within the CSRR structure, effectively confining a higher electric field intensity within the ring.

To achieve a high Q–factor and high resolution sensor, we selected three key parameters to simulate in HFSS. There is a correlation between better impedance matching and higher return loss, with a higher return loss indicating improved impedance matching, which facilitates remote signal transmission and wider temperature testing ranges34. Optimization was performed on the length Lr, width Wr, and ring width a of the CSRR to obtain smaller resonance amplitudes in the S11 curve. Figure 3a shows the response curves of the BCD–MAS at different Lr values. Both resonant frequencies fr1 and fr2 of the sensor decrease as Lr increases, with a more significant shift in fr1 and a slight shift in fr2. Figure 3b displays the variation of resonant frequencies with Wr. The resonant frequencies of the sensor decrease as Wr increases, with a more notable shift in fr1 compared to fr2. As shown in Fig. 3c, when the parameter a increases, the resonant frequencies of the sensor shift towards lower frequencies. Meanwhile, even small changes in parameter a cause significant deviations in the resonant frequencies of the sensor. Therefore, we can obtain a sensor with better performance by adjusting the structural parameters of the CSRR. The physical dimensions of the BCD–MAS are summarized in Table 1.

Experimental

Device fabrication of antenna sensor

Figure 4 shows the preparation process of BCD–MAS, which constructs the sensor based on ceramic processing, screen printing, and high–temperature co–firing technology. The slurry (JIAWEI, China) is processed through a tape casting machine (DL–LYJ–30ME1100, DRON) to form a 99% white porcelain green tape. Ten layers of the prepared green films are stacked and enclosed in an aluminum belt, followed by vacuum press (JUMBO 30, HENKELMAN) under conditions of 75 °C and 20 MPa for 10 min. After lamination, the ceramic cutting machine (CM–1508, KEKO) precisely cuts them into several substrates of sensor sizes, which are then placed in a muffle furnace (KSL-1800X-A1, KEJING) for sintering. In the high–temperature environment, the binders and organic solvents in the slurry quickly decompose and volatilize. Simultaneously, the bonding force between ceramic particles increases, and new chemical bonds are formed between the green tape layers, thereby enhancing the strength of the substrate. After all, the lamination process earlier formed physical bonds, which could be easily separated by very little external force.

The cooked ceramic wafers obtained from the previous processing step were repeatedly wiped with alcohol–dipped dust–free cloths to ensure their cleanliness and tidiness. Screen printing technology was employed to form the metallization patterns on the top surface and the grounding layer on the bottom surface using silver paste (01 H-1803, ESL ELECTROSCIENCE). Subsequently, the wafers were placed in an environment at 120 °C for 10 min to dry, and then sintered to a peak temperature of 850 °C within 185 min, maintaining this temperature for 30 min. After natural cooling, the preparation of BCD–MAS was completed. As described in our previous work36, a dense and high–temperature stable silver film was formed on the ceramic substrate, and the prepared sensor is shown in Fig. 4.

Microstructural characterization

As shown in Fig. 5a–c, the morphological evolution of the silver film of BCD–MAS at different stages, namely post-drying, after high–temperature sintering, and following repeated testing, was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Clear observations were made regarding the shape, size, distribution of silver particles on the sample surface, as well as the growth state of the crystals, which exhibited significant changes at each stage. After the drying process, a thin film of silver–containing mixture was initially formed, with a morphology as depicted in Fig. 5a. The depicted area was characterized by particles of varying sizes, randomly stacked, and an uneven distribution of pores across the surface, giving it a rough overall appearance. Figure 5b shows that crystal particles of similar sizes were tightly arranged, with previous pore structures barely visible. This was due to the decomposition and volatilization of organic components such as binders in the silver paste during sintering, as well as the prolonged exposure of the metal to high temperatures, resulting in the formation of coarse recrystallized grains. As shown in Fig. 5c, the metal film particles on the sensor surface were more tightly packed, with further reduced porosity, and debris filled the gaps between larger particles. This phenomenon could be attributed to the difference in mechanical properties between the top/bottom silver films and the ceramic substrate, as well as inevitable mechanical wear during frequent operation. An accumulative effect was observed during the experiments, where an increase in the number of tests led to changes on the sensor surface. Macroscopically, this manifests as the appearance of scratches and the adhesion of foreign substances, while microscopically, more fine debris can be seen located between large crystal particles. In more severe cases, this can impact the performance or even cause functional failures of the sensor.

Measurement and discussion

To verify the temperature performance of the prepared BCD–MAS, we set up a test platform primarily consisting of a temperature–controlled stage (Yuwei, TC–500), VNA (Ceyear, 3671E), and a computer, as shown in Fig. 6a. The box section of the temperature–controlled stage enables precise control of the thermal environment, while the heating plane provides a stable testing support for the device under test. Prior to the measurements, it is also necessary to perform open–short–load calibration on the VNA using the 20,403 electronic kit. A subminiature version A (SMA) adapter is welded to the feed port of the sensor and connected to the VNA via a coaxial cable to facilitate signal transmission and reception. The sensor is placed above the heating plane, and to prevent the high temperature from damaging the solder joints, the tail end of the sensor is positioned outside the edge of the heating platform to ensure it does not come into contact with the heated surface.

(a) Schematic diagram of the measurement platform and a magnified view of the sensor’s physical image; (b) simulated and measured S11 curves for the BCD–MAS; (c) temperature response curve and partial enlarged view of the BCD–MAS within the range of 25–350 °C; (d) sensitivity fitting curve of the BCD–MAS; (e) Q–factor of the BCD–MAS varies with temperature; (f) results of the stability test for the BCD–MAS; (g) results of the repeatability test for the BCD-MAS.

As shown in Fig. 6b, the measured S11 curve at 25 °C is presented. The results indicate that two distinct resonant peaks appear in the test curve, corresponding to the dual resonant frequencies of the temperature sensor, fr1 = 2.50 GHz and fr2 = 3.24 GHz, respectively. Compared with the simulation curve, the two resonant points in the measured return loss results have shifted to the left by approximately 0.74 GHz and 1.64 GHz. These frequency differences are primarily attributed to the fact that the metal on the top and bottom surfaces of the sensor was modeled as a perfect electric (Perfect E) conductor boundary, whereas the actual sensor fabrication utilized silver, a metal conductor with a relatively lower conductivity. In addition, parasitic capacitances introduced during the fabrication process and/or SMA connectors also contribute to these effects31. Furthermore, it can be observed that the simulated curve exhibits significantly larger resonant amplitudes compared to the measured curve. This is because, during the simulation process, a larger maximum delta s value was set to enhance computational speed, which inevitably compromised computational accuracy to some extent.

When the test conditions were elevated from room temperature of 25–350 °C, the sensor consistently demonstrated excellent responsiveness, with measurement results shown in Fig. 6c. As the temperature increased, it was observed that both resonant frequencies shifted synchronously towards lower frequencies. This change is primarily attributed to the increase in the effective permittivity of BCD–MAS with rising temperature, leading to a corresponding decrease in the resonant frequencies, as discussed in Sect. 2. To more accurately analyze the sensor’s sensitivity, we conducted a linear regression fit analysis on the resonant frequencies across the tested temperature range, as depicted in Fig. 6d. The sensor exhibited a sensitivity of 183 kHz/°C at the resonant frequency fr1 and 177 kHz/°C at fr2. It is worth noting that the sensor demonstrated a significantly enhanced sensitivity at the first resonant point, which is attributed to the high confinement of electric field energy by the CSRR structure. In the fitting results, the coefficient of determination R2>0.99 of the two resonant points, indicating that the sensor has excellent linearity performance. Based on the above model test results, we further explored more valuable data. As can be seen from Fig. 6e, the Q–factors Qfr1 and Qfr2 of the two resonant frequencies peaked at 25 °C, with the maximum Q–factor reaching 1413, and then gradually decreased with increasing temperature, which is related to the decrease in the conductivity of silver at high–temperature. At the same time, we validated the stability of BCD–MAS, as shown in Fig. 6f. Tests were conducted for one hour at five temperature nodes: 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, 300 °C, and 350 °C. The results revealed that the output resonant frequencies fr1 and fr2 remained highly consistent during the insulation tests at 25 °C, 100 °C, 200 °C, and 300 °C. However, when the temperature rose to 350 °C, stability was maintained for only 3 min at the resonant frequencies due to the melting of solder joints under high–temperature. This indicates that the maximum operating temperature of the sensor is 350 °C. As shown in Fig. 6g, we further characterized the repeatability of the sensor. From three sets of tests conducted over a period of 5 days, it can be observed that except for slightly poorer repeatability in frequency shift during the initial phase from 25 °C to 50 °C, the frequency shifts caused by other temperature changes were completely consistent. This is likely due to the instability of the temperature control platform in the low–temperature range. Table 2 provides a comparative evaluation of the BCD–MAS developed in this study with previously reported microstrip patch antenna temperature sensors. The dual–band sensor designed in this paper can operate in higher temperature environments and exhibit higher sensitivity.

Conclusion

This paper presents an integrated microstrip antenna and sensor structure designed based on the principles of electromagnetic interference. Through optimization of the device’s structure and parameters, it achieves dual-band temperature monitoring within the range of 25–350 °C. This design not only enhances spectral efficiency but also improves measurement accuracy through mutual calibration between the two frequency bands. Specifically, the CSRR is loaded onto the radiating patch of an inset-fed microstrip antenna, making the overall structure more compact and endowing it with adjustable operating frequency characteristics. The CSRR, located centrally on the radiating patch, confines the electric field to a localized area within the resonant cavity, rendering it highly sensitive to changes in the substrate’s dielectric constant. Consequently, this significantly enhances the frequency shift, notch depth, and quality factor of the S11 transmission curve during temperature variations. We selected 99% pure alumina ceramic, known for its excellent thermal stability, as the dielectric layer for the sensor, and fabricated the silver-based sensitive structures and ground plane using thick-film screen printing technology. Experimental results show that at room temperature, the resonance frequencies of the sensor are fr1 = 2.50 GHz and fr2 = 3.24 GHz, consistent with simulation outcomes. As the test conditions increase from room temperature to 350 °C, the resonance frequencies of the S11 curve shift linearly to the left, both effectively characterizing the temperature parameter. The sensor demonstrates a maximum sensitivity of 183 kHz/°C, a peak quality factor of 1413, and performs exceptionally well in stability and repeatability tests. Given the requirements of application fields such as the Industrial Internet and resource development, there is an urgent need to develop compact, cost-effective, and easy-to-operate multi-band temperature sensors for real-time monitoring of operational processes, thereby promoting industrial upgrades. To this end, we are exploring the use of Software Defined Radio (SDR) technology to replace the currently used bulky VNA. Furthermore, to address the challenge of high temperatures and mechanical stress at the connection between the sensor and SMA interface, we plan to adopt metal paste welding for high-temperature cables, further extending the working temperature range of the antenna sensor.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. If you would like the research data for this paper, please don’t hesitate to contact me at the address below.E-mail: b20210608@st.nuc.edu.cn.

References

Nyfors, E. Industrial microwave sensors-DA review. Subsurf. Sens. Technol. Appl. 1 (1), 23–43 (2000).

Yao, F. M., Tchafa, A., Jain, S., Tjuatja & Huang, H. Far–field interrogation of microstrip patch antenna for temperature sensing without electronics. IEEE Sens. J. 16, 7053–7060 (2016).

Bhattacharjee, F., Nikbakhtnasrabadi & Dahiya, R. Printed chipless antenna as flexible temperature sensor. IEEE Internet Things 8 (6), 5101–5110 (2021).

Deen, H. Z., Malhat, H. A. E. A. & Refaay, E. A. A. InSb based microstrip patch antenna temperature sensor for terahertz applications. Wirel. Pers. Commun 115, 893–908 (2020).

Sina, K. & Pejman, R. Microwave substrate integrated waveguide resonator sensor for non-invasive monitoring of blood glucose concentration: Low cost and painless tool for diabetics. Measurement 219 (2023).

Sina, K., Pejman, R. & Moein, N. Dual-sensing and dual-frequency microwave SRR sensor for liquid samples permittivity detection. Measurement 160 (2020).

Tchafa, M. & Huang, H. Microstrip patch antenna for simultaneous strain and temperature sensing. Smart Mater. Struct. 27 (6), 065019 (2018).

Gharbi, E., García, R. F., Ahyoud, S. & Gil, I. A review of flexible wearable antenna sensors: Design, fabrication methods and applications. Materials 13 (17), 3781 (2020).

Li, S., Xue, L., Xie & Wan, G. Simultaneous crack and temperature sensing with passive patch antenna. Struct. Health Monitor. 23 (3), 1299–1312 (2024).

Dong et al. Nov., Design and testing of miniaturized dual–band microstrip antenna sensor for wireless monitoring of high temperatures. IEEE Sens. J. 23 (22), 27242–27250 (2023).

Miao, F., Tian, P., Tao, B. & Zang, Y. Passive RFID microstrip antenna sensor for temperature monitoring. Vacuum 201 (2022).

Sanders, J. W., Yao, J. & Huang, H. Microstrip patch antenna temperature sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 15 (9), 5312–5319 (2015).

Liao, Y. T., Chen, Y. C. & Kuo, C. C. Millimeter–wave passive patch antenna for use in wireless high–temperature sensor. Sensor. Mater. 34 (6), 2281–2292 (2022).

Rajesh, G. S. & Kumar, V. A study of CSRR loaded microstrip antenna for multiband applications. 2015 IEEE AEMC., Guwahati, India, pp. 1–2, (2015).

Li, R. et al. Apr., Design of wideband high–gain patch antenna array for high–temperature applications. Sensors 23 (8), 3821 (2023).

Rai, J. K. & Chowdhury, R. P. R. and Machine learning enabled Al2O3 ceramic based dual band frequency reconfigurable dielectric antenna for wireless application. IEEE. T. Dielect. El. In. 31 (5), 2840–2849 (2024).

Atanasova, G. & Atanasov, N. Sep., Small antennas for wearable sensor networks: Impact of the electromagnetic properties of the textiles on antenna performance. Sensors, 20 (18), 5157 (2020).

Arora, C., Pattnaik, S. S. & Baral, R. N. SRR superstrate for gain and bandwidth enhancement of microstrip patch antenna array. Progr. Electromagn. Res. B 76, 73–85 (2017).

Yeo, J. & Lee, J. I. Design of a high–sensitivity microstrip patch sensor antenna loaded with a defected ground structure based on a complementary split ring resonator. Sensors 20 (24) (2020).

Wang, L., Yang, X. X., Lou, T. & Gao, S. A miniaturized differentially fed patch antenna based on capacitive slots. IEEE Antenen. Wirel. Pr. 21 (7), 1472–1476 (2022).

Falcone, F. et al. Effective negative–ε stop–band microstrip lines based on complementary split ring resonators. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compont. Lett. 14 (6), 280–282 (2004).

Baena, J. D. et al. Equivalent–circuit models for split–ring resonators and complementary split–ring resonators coupled to planar transmission lines. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 53 (4), 1451–1461 (2005).

Bonache, J., Gil, M., Gil, I., Garcia, J. G. & Martin, F. On the electrical characteristics of complementary metamaterial resonators. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compont. Lett. 16 (10), 543–545 (2006).

Sina, K., Pejman, R. & Mina, F. Real-time measurement of liquid permittivity through label-free meandered microwave sensor. IETE J. Res. 70 (5), 4606–4616 (2023).

Beria, Y., Das, G. S., Buragohain, A. & Chamuah, B. B. Highly sensitive miniaturized octagonal DS–CSRR sensor for permittivity measurement of liquid samples. IEEE T Instrum. Meas. 72 (9512109), 1–9 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Shou, H., Liu, R., Ding, G. & Mei, Z. A CSRR–based dual–peaks antenna sensor for full characterization of magneto–dielectric materials. IEEE Sens. J. 23 (21), 25947–25957 (2023).

Ong, N. T. J., Yee, S. K. & Ashia, A. Y. I. Design of microwave sensor based on rectangular double split ring resonator for water quality monitoring. 2020 IEEE SCORED., Batu Pahat, Malaysia, pp. 111–116 (2020).

Yee, T. S., Akbar, M. F., Ghazali, N. A. & Mohamed, M. F. P. Defects detection using complementary split ring resonator with microstrip patch antenna. In Proc. 11th Int. Conf. on Robotics, Vision, Signal Processing and Power Applications, 829, 625–631 (2022).

Raj, S., Tripathi, S., Upadhyay, G., Tripathi, S. S. & Tripathi, V. S. An electromagnetic band gap–based complementary split ring resonator loaded patch antenna for glucose level measurement. IEEE Sens. J. 21 (20), 22679–22687 (2021).

Cheng, X., Senior, D. E., Kim, C. & Yoon, Y. K. A compact omnidirectional self–packaged patch antenna with complementary split–ring resonator loading for wireless endoscope applications. IEEE Antenn. Wirel. Pr. 10, 1532–1535 (2011).

Tata, U., Huang, H., Carter, R. L. & Chiao, J. C. Exploiting a patch antenna for strain measurements. Meas. Sci. Technol. 20 (1), 015201 (2009).

Pozar, D. M. Microwave Engineering (Wiley, 2012).

Sun, Z. F. et al. Dec., A miniaturized wireless passive frequency selective surface sensor for high–temperature application. IEEE Sens. J. 22 (23), 22734–22740 (2022).

Liu, W., Xu, L. & Zhan, H. Design of 2.4 ghz/5 ghz planar dual–band electrically small slot antenna based on impedance matching circuit. Aeu –Int J. Electron. C. 83, 322–328 (2018).

Rai, J. K. et al. Nov., Machine learning-enabled two-port wideband MIMO hybrid rectangular dielectric resonator antenna for n261 5G NR millimeter wave, Int. J. Commun. Syst. 37 (16) (2024).

Zhang, X. X. et al. Apr., Metamaterial high–temperature sensor based on all–planar substrate integrated waveguide. IEEE Sens. J. 24 (7), 9916–9924 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported in part by the Key Research and Development Plan of Shanxi Province (No. 202102030201005), the Applied Basic Research Program Youth Project of Shanxi Province (No. 202203021222070, No. 20210302124274), the National Nature Foundation Youth Program (No. 52105594), and Shanxi Scholarship Council of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XX.Z. wrote the main manuscript text. YL.H. and QL.T. methodology and Writing – review & editing. R.F., HT. S., and JQ.P. data curation and prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Hou, Y., Feng, R. et al. Temperature sensor with adjustable frequency band integrated with antenna and perception. Sci Rep 15, 8734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91120-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91120-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Tri-Delta and CSRR Loaded Dodecagon Antenna as Temperature Sensor for Industrial Medical and 5G Applications

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Electrical Engineering (2025)