Abstract

Due to the design challenges and low performance of engines in green fuels, the researchers started to investigate fuel blends. The inlet parameters also will influence the performance and, emission characteristics of the engines. Considering the effect of injection pressure, the current study revealed the clarity of distinct feedstocks that may be used effectively with esterified petrol blends at different injection pressure. This study has considered the various non-edible vegetable oil-based fuels such as Pongamia methyl ester-Gasoline blend [PME-5G], Jatropha methyl ester- petrol blend [JME-5G], Neem methyl ester- petrol blend [NME-5G], Mahua methyl ester- petrol blend [MME-5G], Dairy scum methyl ester – petrol blend [DME-5G], and Used cooking oil methyl ester – petrol blend [UME-5G] for investigation. The entire test is carried out in the CI engine of irrigation water pumping systems under the distinct injection pressures of 210, 230, and 250 bar with respective loading conditions of 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%. The output parameters such as Brake power, Thermal efficiency, Specific fuel consumption, heat release rate, cylinder pressure and emission stanadrds are elaborately discussed. The final results show the maximum performance at higher injection pressure which is reverse in the case of emissions that exhibited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

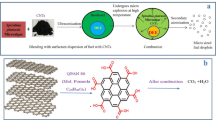

Vegetable oils have been utilized as an alternative to petroleum diesel since the introduction of internal combustion engines1. Vegetable oil or its derivatives mixed with diesel, on the other hand, can cause several long-term problems with internal combustion engines. Fatty acid methyl ester has grown in popularity in recent years as researchers investigate the use of vegetable oils and animal fat derivatives for biodiesel, a liquid fuel. Non-edible oils such as linseed, neem, Mahua, Jatropha curcas, Kusum, Pongamia pinnata, Karanja oil, and, castor can be gathered and converted into biodiesel, positioning India as a potential leader in biodiesel production2,3,4,5. Even, unused non-edibles such as industrial leather waste and waste pork fatty oil are utilized for biofuel extraction, and ignition enhancers are used in CRDI engines6,7. The aluminium nitrate (Al (NO3)3) nanoparticles and graphene oxide nanoplates (GONPS) are mixed with waste leather oil in the proportion of 50 ppm as catalysts to enhance the ignition process. A new attempt at dual fuel blend mode which runs by hydrogen gas-sapota seed biodiesel and, Ammonia (NH3)-Cashew nut shell oil was investigated on diesel engines and better performance was obtained8,9. The cashew nut shell oil is also tried for reactivity-controlled compression ignition engine (RCCI) along with Al2O3nanoparticles to improve the performance and reduce the emission10. Clean vegetable oils or diesel blends, can produce a variety of long-term issues with compression ignition engines, such as lubricating oil dilution due to injector deposits, crankcase polymerization, injector pump failure, poor atomization, ring sticking, and injector coking. Vegetable oils have undesirable properties due to their inherent qualities, such as polyunsaturation, high viscosity, and poor volatility11,12. B20, a biodiesel/diesel blend consisting of 20% biodiesel and 80% diesel, could be used in engines without any changes13,14. The larger volatility range of gasoline-diesel blending may aid in meeting these aims when using fuels with prolonged Ignition delays and lower injection pressure to improve combustion stability and significantly reduce HC and CO emissions while not affect NOx or smoke emissions15,16,17. The exhaust emission analysis of different non-edible oils such as Simarouba, jojoba, linseed, and nagchampa with conventional diesel in a diesel engine under different loading conditions was performed18,19. The emission characteristics of Jatropha curcas with waste wood producer gas and coconut shell imitative producer gas for dual fuel engine mode are discussed and better specific fuel consumption is obtained compared to conventional fuel20. Similarly, linseed oil with rice husk producer gas is investigated and oxides of nitrogen and smoke have diminished21. The performance, combustion, and emission characteristics of a diesel engine were investigated in this context with Pongamia methyl ester-Gasoline blend [PME-5G], Jatropha Methyl ester blend with petrol [JME-5G], Neem Methyl ester blend with petrol [NME-5G], Mahua Methyl ester blend with petrol [MME-5G], Dairy scum Methyl ester blend with petrol [DME-5G], and Used cooking oil Methyl ester blend with petrol [UME-5G] as biodiesel fuel. This study looks at how injection pressure affects diesel engine performance, combustion, and emissions. The test used three injection pressures (210 bar, 230 bar, and 250 bar) with a constant compression ratio (16:1). Low-carbon alcohols, such as methanol and ethanol, have sparked widespread attention as diesel fuel additives due to their simple production techniques and high oxygen content, which improves combustion characteristics while cutting emissions2. Bio-diesel is a clean energy source that may be used in diesel engines, boilers, and other combustion equipment22. Biodiesel offers some advantages over fossil diesel fuel in terms of combustion23,24. These alternative biodiesel combinations provide superior results and address existing difficulties with standard biodiesels. When utilizing biodiesel to fuel an engine, a greater compression ratio and injection pressure are suggested23. Biodiesel includes oxygen, which allows the fuel in the engine to burn entirely25. Even though all biodiesels and their blends have a greater flash point than diesel, transesterification reduces it26,27. The addition of a small amount of biodiesel to diesel raises its flash point28. In terms of efficiency and emissions, biodiesel with a 15% DEE (Di ethyl ether) blend outperformed biodiesel without a 15% DEE blend29. Biodiesel is gaining popularity among the various types of biofuels due to its features and chemical makeup, which allow it to be blended with diesel30. Although biodiesel has some benefits over conventional diesel fuel, there is lot of challenges still alive in achieving greater efficiency than diesel fuel. Design parameters and operating conditions of the engine are playing important role in outcomes. On the other hand, modifying the engine’s geometry involves technical difficulty in compromising scientific standard and implementation. However, controlling the engine operating parameters are one of the possible ways of improving engine performance where injection pressure is a key factor, considered in this study. Instead of testing and revealing the performance of a single blends, the current study has included familiar non edible fuel blends and compared the performance under the selected pressure & load. This provides a detailed knowledge for compatibility of biodiesel blends in compression ignition engine.

Materials and methods

The Pongamia methyl ester-Gasoline blend [PME-5G] and the Jatropha methyl ester blend with petrol [JME-5G], Neem NME-5G, MME-5G, and DME-5G are methyl ester blends with petrol. Used cooking oil Methyl ester blended with petrol [UME-5G] as a biodiesel fuel used to test combustion elements engine performance such as brake power, brake specific fuel consumption, and brake thermal efficiency, as well as emission parameters such as CO (Carbon Monoxide), UBHC (Unburnt hydro carbon), and NOx (Nitrogen oxides) of CI engines. Each experimental trial was conducted with a constant compression ratio of 16:1, a constant engine speed of 1500 rpm, and varying injection pressures of 210 bar baseline, 230 bar, and 250 bar at sequential engine loads of 0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%.

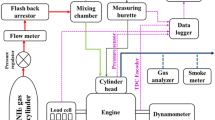

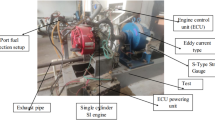

Experimental setup

An experimental setup consists of computer-based multi-fuel engine test equipment and a gas analyzer for measuring engine emissions. Emissions of oxygen, hydrocarbons, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and other components are all measured. A gas analyzer (supplied by Indus Scientific Pvt Ltd.) measures carbon monoxide (%), carbon dioxide (%), and oxygen levels in the exhaust gas (%). Sonicators are used to agitate various materials using ultrasonic pulses. A medium is used to carry sound waves. The device converts sound energy into mechanical energy. A mechanical stirrer is a laboratory magnetic device with a spinning magnetic field that quickly spins a stir bar immersed in a liquid, churning it. The water-cooled reflux condenser consisted of a vertical tube-side condenser through which vapour flowed upward. It’s also known as a knockback or vent condenser. Figure 1 depicts the research engine test layout. Table 1 lists the technical specifications of the diesel engine, whereas Table 2 lists the accuracy and uncertainty measures, as well as the engine’s predicted parameters.

Parameters evaluated

To validate the biodiesel, mix in a compression ignition engine, the following parameters were investigated. Performance characteristics include brake-specific fuel consumption, brake power, and brake thermal efficiency. Combustion parameters such as cylinder pressure and heat release are related to engine crank angle. Emission criteria include carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and unburned hydrocarbons.

Result & discussions

Engine performance was evaluated for all of the aforementioned petrol-mixed samples separately at various injection pressures (IP), constant speed, and compression ratios at different engine loads. To solve the challenges related to fuel replacement in unmodified C I engines, an investigation of performance measures is necessary. The measures include braking power (BP), brake thermal efficiency (BTE), and brake-specific fuel consumption (BSFC).

Engine performance parameters

Brake specific fuel consumption (BSFC)

Figure 2a depicts the relationship between brake-specific fuel consumption and engine load for PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel blend, and diesel with calorific values of 39,400 KJ/kg, 40,063 KJ/kg, 40,095 KJ/kg, 39,994 KJ/kg, 39,585 KJ/kg, 37,955 KJ/kg, and 44,800 KJ/kg, respectively. Because the DME-5G biodiesel blend has the lowest calorific value of all other samples and diesel, the engine consumes more fuel at higher engine loads (60%, 80%, and 100%) at all three injection pressures of 210 bar, 230 bar, and 250 bar, as shown in Fig. 2a and b, and 2c.

At 210 bar injection pressure (Fig. 2a), BSFC values for MME-5G, PME-5G, and NME-5G engines at 80% engine load are 0.32 kg/KWh, 0.33 kg/KWh, and 0.34 kg/KWh, respectively, compared to 0.28 kg/KWh for diesel. At 230 bar injection pressure (Fig. 2b), fueling MME-5G, PME-5G, NME-5G, and JME-5G at 80% engine load yields very similar values of 0.29 kg/KWh, 0.34 kg/KWh, 0.35 kg/KWh, and 0.36 kg/KWh, respectively, when compared to Diesel at 0.32 kg. Similarly, at a higher injection pressure of 250 bar (Fig. 2c), fueling MME-5G, PME-5G, NME-5G, and JME-5G at 80% engine load yields extremely similar values of 0.19 kg/KWh, 0.201 kg/KWh, 0.22 kg/KWh, and 0.24 kg/KWh, respectively, when compared to diesel at 0.16 kg/KWh. At a greater injection pressure of 250 bar, the PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, and JME-5G showed similar results to diesel fuel at higher engine loads (60%, 80%, and 100%), as shown in Fig. 2c. Previous studies have demonstrated that as engine load increases from zero to 100%, brake-specific energy and fuel consumption decrease2,15.

As the engine’s load increases, the mean effective cylinder pressure and mechanical efficiency rise, resulting in lower specific fuel consumption31,32. At 60% and 80% engine load, the BSFC of the DME-5G blend is 0.46 and 0.38 kg/KWh, respectively. At 60% and 80% engine load, diesel produces 0.37 Kg/KWh and 0.28 Kg/KWh, respectively. At 60% and 80% engine load, the remaining samples range between 0.38 Kg/KWh and 0.42 Kg/KWh. DME-5G blend appears to be the ideal sample because to its extremely near BSFC of 19% and 26% higher than diesel for the specified engine load.

Brake thermal efficiency (BTE)

Figure 3a depicts the distribution of brake thermal efficiency versus engine load at 210 bar of injection pressure. Figure 3a shows that when the engine load increases, the braking thermal efficiency for PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel blends, and diesel steadily increases. Diesel has BTE values of 26%, 30%, and 29% for engine loads of 60%, 80%, and 100%, respectively, at 210 bar injection pressure. At 210 bar injection pressure and 80% engine load, the BTE values for PME-5G, NME-5G, and MME-5G engines are 27.94%, 26.45%, and 25.85%, respectively, compared to 30.3% for diesel. NME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and PME-5G all have a close association with BTE for Diesel. DME-5G has the lowest brake thermal efficiency across all engine loads due to its lower Calorific value.

Diesel has BTE values of 28%, 29%, and 31% for engine loads of 60%, 80%, and 100%, respectively, at an injection pressure of 230 bar. At this injection pressure, MME-5G, NME-5G, and JME-5G show extremely similar results of 27.68%, 25.17%, and 24.74%, respectively, when compared to Diesel at 28.69%. At higher engine loads, the MME-5G and Diesel bear a remarkable likeness. Figure 3b shows that NME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and PME-5G have a close association with the BTE of Diesel.

Diesel has BTE values of 25%, 26%, and 28% for engine loads of 60%, 80%, and 100%, respectively, at 250 bar injection pressure. At this injection pressure, fueling MME-5G, NME-5G, and JME-5G at 80% engine load yields extremely similar values of 23.89%, 23.73%, and 22.65%, respectively, compared to Diesel at 25.68%. NME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and PME-5G all have a close association with diesel BTE, as seen in Fig. 3c. At higher injection pressures of 250 bar, brake thermal efficiency declines by 5% on average. At a standard injection pressure of 200 bar, methyl ester neem oil has lower braking thermal efficiency than diesel fuel at all loads due to its high viscosity and poor mixture formation33.

Brake power (BP)

Figure 4a displays the brake power produced at all prescribed engine loads when the engine is fuelled with PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel, or diesel. The profiles produced for PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel blend, and Diesel indicate a direct link between braking power and engine load. At 210 bar injection pressure, brake power of UME-5G, DME-5G and PME-5G for 80% engine load shows very closer values of 3.19 KW, 3.16 KW and 3.15 KW respectively while compared to Diesel with 3.22 K. At this stage, diesel produces 3.22 KW of brake power, while the UME-5G produces 3.19 KW of brake power, which is 0.93% less than diesel. At higher injection pressure of 230 bar, UME-5G, JME-5G and PME-5G for 80% engine load shows very closer values of 3.23 KW, 3.21 KW and 3.15 KW respectively while compared to Diesel with 3.2 KW. At this stage, the brake power produced by Diesel is 3.2 KW, whereas the UME-5G produced 3.23 KW, which is 0.92% more than Diesel. Figure 4b shows that the PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, and DME-5G biodiesel blends had remarkably similar results at 230 bar injection pressure. Similarly at higher injection pressure of 250 bar, UME-5G, JME-5G and PME-5G for 80% engine load shows very closer values of 3.18 KW, 3.14 KW and 3.13 respectively while compared with Diesel with 2.98 KW. Here, the brake power produced for Diesel is 2.98 KW, whereas the UME-5G produced 3.18 KW of brake power, which is 6% greater than Diesel.

At a higher injection pressure of 250 bar, the brake power of the PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, and DME-5G biodiesel blends exceeds that of diesel, as illustrated in Fig. 4c. As the engine load grows, so does the brake power provided by the fuel sample. When compared to diesel, the castor oil blend sample had significantly lower brake power under varying engine load conditions34.

Engine combustion characteristics

Cylinder pressure (CP)

Figure 5a displays the cylinder pressure developed within an engine cylinder versus crank angle at 80% engine load when the engine was running at 210 bar of injection pressure and fuelled with PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel and diesel. The cylinder pressure distribution curve displayed by all blended samples is comparable to the Diesel. At 210 psi of injection pressure and 80% engine loading, the UME-5G produces 61.93 bar of cylinder pressure, while the Diesel exerts 59.26 bar. UME-5G has 4.3% higher cylinder pressure than diesel. The sample blends, such as NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, and DME-5G, provide very close cylinder pressure to that of diesel.

Similarly, with 230 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine loading, MME-5G produces 62.63 bar and Diesel exerts 62.47 bar of cylinder pressure. MME-5G has 0.25% higher cylinder pressure than diesel. Figure 5b shows sample blends such as PME-5G, NME-5G, JME-5G, and UME-5G yield cylinder pressures that are extremely near to those of diesel. Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine loading, JME-5G produces 61.17 bar and Diesel exerts 61.19 bar of cylinder pressure, respectively. JME-5G has 0.03% lower cylinder pressure than diesel. Figure 5c shows that sample blends such as MME-5G and UME-5G create cylinder pressures comparable to diesel.

The cylinder peak pressure is determined by the biodiesel’s early combustion rate, which is controlled by the uncontrolled heat release phase. Biodiesel has a lower cylinder peak pressure than conventional diesel because of its high viscosity and low volatility. According to studies, the cylinder peak pressure of biodiesel increases as the engine load increases due to the volume of biodiesel injected into the cylinder2,35. When utilizing biodiesel and similar mixes, the early peaking features require extra attention to guarantee that the peak pressure occurs after TDC for safe and efficient operation. Otherwise, a peak pressure around or before TDC results in significant engine knock, reducing engine durability28. When DEE (diethyl ether) is added to neat biodiesel, the peak pressure rises relative to neat biodiesel. This is because DEE has a greater cetane number and is more flammable, resulting in a better-premixed combustion phase and a higher peak pressure29. At 100% engine load, the average cylinder pressure for PME-5 G and diesel is similar36. If a fuel ignites slower than diesel fuel and combustion happens after the fuel and air have had more time to mix, both pollutants could be lowered simultaneously, eliminating the well-known soot-NOx trade-off17.

Heat release rate

Figure 6a displays the heat released rate during combustion within an engine cylinder vs. crank angle at 80% engine load, with the engine operating at 210 bar injection pressure and fuelled by PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel and diesel. The heat release rate distribution curves of all blended samples are comparable to the Diesel. At 210 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine loading, UME-5G produces 35.15 J/degree CA, while Diesel releases 37.61 J/degree CA of heat release rate. UME-5G has a 6.5% lower heat release rate than diesel. Sample blends such as DME-5G and NME-5G produce results similar to diesel, as illustrated in Fig. 6a. Similarly, at 230 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine loading, MME-5G produces 40.9 J/degree CA of heat release rate, while Diesel releases 38.62 J/degree CA. MME-5G has a 5.5% higher heat release rate than diesel. Sample blends such as NME-5G and PME-5G produce values similar to diesel, as illustrated in Fig. 6b.

Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine loading, the JME-5G produces 35.27 J/degree CA of heat release rate, whereas the Diesel releases 31.51 J/degree CA. JME-5G has a 10.6% higher heat release rate than diesel. The sample blends NME-5G, MME-5G, and PME-5G generate values similar to Diesel, as shown in Fig. 6c. Biodiesel has a lower calorific value than diesel, therefore it requires more fuel to maintain the engine operating at a steady speed under varying loads2. According to the heat release rate, biodiesel and its mixes had a shorter igniting delay than diesel. Biodiesel and comparable mixes have a less intense premix combustion phase due to the shorter ignition delay.

When utilising diesel, however, increased fuel accumulation over a somewhat longer delay time resulted in a faster rate of heat release. Because of the shorter delay, biodiesel and equivalent mixtures reach their maximal heat release rate earlier than neat diesel. Biodiesel and biodiesel blends, on the other hand, emit slightly less heat in the late combustion phase than diesel.

This is because elements with a higher oxygen concentration can complete the combustion of any remaining fuel after the main combustion period and continue to burn in the late combustion phase28. The net heat release rate (NHRR) increased as IP increased due to higher cylinder pressure and combustion temperature37. The vaporization of the fuel stored during the ignition delay at the start has a negative heat release rate. This becomes positive as the combustion process begins. The premixed fuel-air combination burns swiftly following the ignition delay phase, followed by diffusion combustion, which is governed by the fuel-air mixing velocity38. As the load rose, the heat emitted in the premixed combustion phase stayed roughly constant, whereas the heat released in the regulated combustion phase increased39.

Engine emission characteristics

Carbon monoxide (CO)

Figure 7a displays the percentage of carbon monoxide emitted during engine exhaust versus engine load when the engine is run at 210 bar injection pressure and fuelled with PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel and diesel. Figure 7a shows that the percentage of carbon monoxide emitted with each successive increment in engine load steadily increases for diesel and all sample mixes. At 80% engine load, CO emission by Diesel is 0.915%, whereas NME-5G produced the least content of all samples, 0.604% of CO percentage. The NME-5G emitted 33.9% less CO than the diesel. The sample blends such as PME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emitted lower CO emissions compared to diesel emissions. As shown in Fig. 7b, the sample blends PME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G had lower CO emissions compared to Diesel emissions. At 230 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, CO emissions by Diesel were 0.983%, while CO emissions by NME-5G were in the range of 0.821%.

Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, diesel emits 0.994% of CO, while NME-5G emits the least amount of CO, around 0.744%. The NME-5G emitted 25.1% less CO than the diesel. Figure 7c shows that sample mixes such as PME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emit less CO than diesel emissions. When the injection pressure is increased to 200 bar, CO emissions are minimized.

Increased injection pressure reduces CO emissions by improving fuel-air mixing and full combustion40. Increased injection pressure reduces smoke density and CO emissions while increasing NOx emissions in a diesel engine powered by an ethanol-diesel fuel combination41.

Carbon dioxide

Figure 8a displays the percentage of carbon dioxide emitted during engine exhaust versus engine load while the engine is operated at 210 bar injection pressure and fuelled with PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel and diesel. Figure 8a shows that the percentage of carbon dioxide released with each successive increment in engine load steadily increases for diesel and all sample mixes. At 80% engine load, diesel emits 8.62% CO2, while PME-5G emits only 7.24% CO2. PME-5G released 16% less CO2 emissions than the diesel. Sample mixes such as NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emitted less CO2 than diesel emissions. Similarly, at 230 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, CO2 emissions by diesel are 8.65%, while UME-5G emits the least CO2 content, at 7.587%. UME-5G emitted 12% less CO2 than the Diesel.

Figure 8b shows that sample mixes such as NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, PME-5G, and DME-5G emitted less CO2 than diesel. Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, CO2 emissions from diesel are 8.92%, whereas UME-5G emits the least amount of CO2 emissions, at 8.06%. UME-5G released 9.6% less CO2 emissions than the diesel. Figure 8c shows that sample blends such as NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, PME-5G, and DME-5G emitted less CO2than diesel. The increased injection pressure lowers HC, NOx, and smoke emissions while increasing CO and exhaust temperature23. Increased injection pressure and methyl ester content in diesel cause higher CO2emissions. This is because higher injection pressure produces finer fuel spray, which properly blends fuel and air, completing the combustion process42. The CO2percentage emission pattern for PME-5 G biodiesel blends is nearly identical to that of diesel fuel for all engine load settings (0%, 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100%)36.

Unburned hydrocarbons

Figure 9a displays the ppm of unburned hydrocarbons emitted during engine exhaust versus engine load while the engine was running at 210 bar of injection pressure and fuelled with PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel and diesel. Figure 9a shows that the ppm of unburned hydrocarbons released as engine load increases progressively for diesel and all sample mixes. At 80% engine load, diesel emits 226 ppm of unburned hydrocarbons, while JME-5G emits the least amount, around 126 ppm of unburned hydrocarbons. JME-5G produced 44% less unburned hydrocarbon emissions than diesel.

The sample blends NME-5G, MME-5G, PME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G produced fewer unburned hydrocarbons than diesel emissions. Similarly, at 230 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, diesel emits 280 ppm of unburned hydrocarbons, while JME-5G emits the least amount, around 219 ppm of unburned hydrocarbons. JME-5G emitted 21% less unburned hydrocarbons than diesel. Figure 9b shows that sample blends such as NME-5G, MME-5G, PME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emitted fewer unburned hydrocarbons than diesel.

Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, diesel emits 248 ppm of unburned hydrocarbons, while JME-5G emits the least amount, around 215 ppm of unburned hydrocarbons. JME-5G emitted 13% less unburned hydrocarbons than diesel.

Figure 9c shows that sample mixes such as NME-5G, MME-5G, PME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emitted fewer unburned hydrocarbons than diesel. Because of increased fuel burning at higher Injection Pressure, HC decreases considerably as Indicated Power increases. The decrease in HC emissions as the blend proportion increases could be attributed to full combustion due to the increased oxygen concentration43,44. High-pressure injection was used to significantly reduce particle emissions while having little effect on hydrocarbon emissions and slightly raising NOx emissions45,46.

Oxides of nitrogen

Figure 10a displays the ppm of nitrogen oxides emitted during engine exhaust versus engine load while the engine was running at 210 bar of injection pressure and fuelled with PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, JME-5G, UME-5G, DME-5G biodiesel and diesel. Figure 10a shows that the ppm of nitrogen oxides emitted as engine load increases progressively for diesel and all sample blends. At 80% engine load, diesel emits 242 ppm of oxides of nitrogen, while JME-5G emits 147 ppm. JME-5G emitted 39% fewer oxides of nitrogen than diesel. The sample blends, such as NME-5G, MME-5G, PME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G, emitted less nitrogen oxides than diesel emissions.

Similarly, at 230 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, the ppm of Oxides of Nitrogen by Diesel is 161 ppm, but the JME-5G emits the least amount, in the range of 169 ppm. JME-5G emitted 4.7% higher oxides of nitrogen than diesel. Figure 10b shows that sample blends such as NME-5G, MME-5G, PME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emit more nitrogen oxides than diesel emissions. Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure and 80% engine load, diesel emits 306 ppm of oxides of nitrogen, whereas JME-5G emits the least amount, in the region of 200 ppm of oxides of nitrogen. JME-5G emitted 34% less oxides of nitrogen than the diesel.

Figure 10c shows that sample mixes such as NME-5G, MME-5G, PME-5G, UME-5G, and DME-5G emit fewer nitrogen oxides than diesel emissions. It was recommended that high injection pressure be employed to reduce smoke, CO, and UHC emissions, and low injection pressure to reduce NOx and CO2emissions37,47. Higher injection pressures of up to 250 bar result in considerable performance improvements for all examined fuels, albeit to varied degrees. With this optimal injection pressure, the B20 was discovered to have the best performance characteristics48.

The temperature inside the cylinder has a considerable influence on NOx creation, and as the temperature rises, so does the amount of NOx produce44,49. In the same way that increasing the load raises the fuel-air ratio, increasing the KOME proportion raises the oxygen content, increasing NOx emissions50,51. NOx and carbon dioxide emissions increased as injection pressure increased, but smoke, HC, and CO emissions decreased52,53.

Conclusion

The performance of the engine exhibited by the compression ignition engine at three injection pressures reflects clear differences from all the distinguished synthesized samples.

-

DME-5G blend appears to be the ideal sample because to its extremely near BSFC of 19% and 26% higher than diesel for the specified engine load. At a greater injection pressure of 250 bar, the PME-5G, NME-5G, MME-5G, and JME-5G showed similar results to diesel fuel at higher engine loads (60%, 80%, and 100%).

-

At a higher injection pressure of 250 bar, fueling MME-5G, NME-5G, and JME-5G at 80% engine load yields extremely close BTE values of 23.89%, 23.73%, and 22.65%, respectively, compared to Diesel at 25.68%. The maximum efficiency difference lies below 11%.

-

Compared to the injection pressure at 210 bar, fuelling at higher injection pressure provided the very close Brake power. Particularly, at injection pressure of 250 bar upon fuelling UME-5G, JME-5G, and PME-5G for 80% engine load shows 3.18 KW, 3.14 KW, and 3.13 respectively which is very close to Diesel with 2.98 KW.

-

At 210 bar of injection pressure for 80% engine loading UME-5G exhibits 4.3% more-cylinder pressure than Diesel. At 230 bar of injection pressure for 80% engine loading MME-5G exhibits 0.25% more-cylinder pressure than Diesel. Similarly, at 250 bar of injection pressure for 80% engine loading JME-5G exhibits 0.03% less cylinder pressure than Diesel.

-

Heat release rate is lower at injection pressure 210 bar and higher at 230 & 250 bar under 80% engine loading. UME-5G has lower heat release of 6.5%, MME-5G & JME-5G 6.5% have high release rate of 5.5% & 10.6% than diesel respectively.

-

Carbon monoxide released by the engine at an injection pressure of 210 bar upon fuelling NME-5G, JME-5G, and MME-5G for 80% engine load shows lesser values of 0.604%, 0.607%, and 0.617% respectively while compared to Diesel with 0.915%. The rate of CO is more at higher injection pressure.

-

At 210 bar injection pressure and 80% engine load, carbon dioxide emissions from PME-5G, UME-5G, and MME-5G engines are 7.24%, 7.61%, and 7.65%, respectively, compared to 8.62% for diesel. The rate of CO2 is more at higher injection pressure.

-

Unburned hydrocarbon released by the engine at an injection pressure of 210 bar upon fuelling JME-5G, NME-5G, and MME-5G for 80% engine load shows lesser values of 126 ppm, 127 ppm, and 145 ppm respectively while compared to Diesel with 226 ppm. The rate of UBHC is more at higher injection pressures.

-

Nitrogen oxides emitted by JME-5G, NME-5G, and PME-5G engines at 210 bar during 80% engine load were 147, 152, and 179 ppm, respectively, compared to 242 ppm for diesel.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Cc:

-

cubic capacity

- Mm:

-

millimetre

- Rpm:

-

revolutions per minute

- Nm:

-

Newton metre

- HP:

-

Horse power

- Ppm:

-

parts per Millenium

- Kg:

-

Kilogram

- kW:

-

Kilowatt

- psi:

-

pounds per square inch

- °C:

-

Degree Celsius

- PME:

-

Pongamia methyl ester

- JME:

-

Jatropha methyl ester

- NME:

-

Neem methyl ester

- MME:

-

Mahua methyl ester

- DME:

-

Dairy scum methyl ester

- UME:

-

Used cooking oil methyl ester

- DEE:

-

Di ethyl ester

- CI:

-

Compression ignition

- CRDI:

-

Common rail direct injection

- RCCI:

-

reactivity controlled compression ignition engine.

- IP:

-

Injection pressure.

- CP:

-

Cylinder pressure.

- BTE:

-

Brake thermal efficiency.

- BSFC:

-

Brake specific fuel consumption.

- BP:

-

Brake power.

- UBHC:

-

Unburnt hydrocarbon.

References

Mohamed Selim, Y. E., Haik, Y. & Al-Omari, S. A. Emad Elnajjar. Combustion of waste chocolate oil biofuel in a diesel engine. Int. J. Amb En. 35 (2), 60–70 (2014).

Ashok, B. & Nanthagopal, K. Eco-friendly biofuels for CI engine applications. Advances in Eco-Fuels for a sustainable environment. Woodhead Publishing Ser. Energy. 407–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102728-8.00015 (2019).

Manikanda Prabu, N. & Nallusamy, S. Thirumalai Rasu. Experimental analysis of Jatropha curcas Bio-Diesel for optimum blend characteristics. Bonf Int. J. Ind. Manag Sci. 3 (2), 63–69 (2013).

Manikanda Prabu, N., Senthil Kumar, T. & Nallusamy, S. Effect of solvent ether (DEE) with J20 biodiesel on internal combustion engine. Appl. Mec Mat. 592–594, 1520–1525 (2014).

Swarup Kumar Nayak & Kumar, P. C. M. A. Gyana Ranjan behera. & Biswajeet Nayak. Experimental investigation on property analysis of Karanja oil Methyl ester for vehicular usage. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 39 (3), 306–312 (2017).

Mohanrajhu, N., Sekar., S. & Sureshkumar, R. Ravikumar Jayabal. Screening nano additives for favorable NOx/smoke emissions trade-off in a CRDI diesel engine fueled by industry leather waste fat biodiesel blend, Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. 187, 332–342 (2024).

Ravikumar Jayabal. Optimization and impact of modified operating parameters of a diesel engine emissions characteristic utilizing waste fat biodiesel/di-tert-butyl peroxide blend. Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. 186, 694–705. (2024).

Ravikumar Jayabal. Effect of hydrogen/sapota seed biodiesel as an alternative fuel in a diesel engine using dual-fuel mode. Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. 183, 890–900. (2024).

Ravikumar Jayabal, G. M., Lionus Leo, M., Chrispin Das, S., Sekar & Arivazhagan, S. Impact of ammonia energy fraction on improving thermal efficiency and emissions of ammonia/biodiesel in dual fuel diesel engine. Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. 188, 1398–1410 (2024).

Lionus Leo, G. M. et al. Experimental evaluation and neural network modelling of reactivity-controlled compression ignition engine using cashew nut shell oil biodiesel-alumina nanoparticle blend and gasoline injection. Ener 182, 128923 (2023).

Harish, H., Kumar, S., Rajanna, C. R., Prakash, G. S. & S.& Experimental investigation on the performance and emission characteristics of edible & Non-Edible oil. Int. J. Emer Tech. Adv. Eng. 4 (10), 648–655 (2014).

Ramesh Appusamy, Chandrasekaran, K. & Yogesha, K. B. Manikanda Prabu Narayanasamy. Compatibility study on Calophyllum inophyllum Methyl ester biodiesel as alternative fuel for IC engines. Environ. Eng. Manag J. 23 (1), 169–181 (2024).

Orsavova Jana. Mlcek Jiri. fatty acids composition of vegetable oils and its contribution to dietary energy intake and dependence of cardiovascular mortality on dietary intake of fatty acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 (6), 12871–12890 (2015).

Anh, N., Phan & Tan, M. Phan. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oils. Fuel 87, 3490–3496 (2008).

Kantharaju, T., Harish, H., Rajanna, S. V. S. & Prakash, G. S. Performance and emission characterization of waste chicken fat biodiesel as an alternate fuel. Int. J. Emer Tech. Adv. Eng. 5 (5), (2015).

Nallusamy, S., Manikanda, N. & Prabu Analysis of performance, combustion and emission characteristics of biofuel of novel pine oil. Ras J. Chem. 10 (3), 873–880 (2017).

., Hyun Woo Won & Pitsch, H. Nigel Tait. & Gautam Kalghatgi. Some effects of gasoline and diesel mixtures on partially premixed combustion and comparison with the practical fuels gasoline and diesel in a compression ignition engine, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. D: J. Auto.Eng. 226, 1259; (2012). 10.1177%2F0954407012440075

Swarup Kumar Nayak., Gyana Ranjan Behera., Purna Chandra Mishra. & Sagar Kumar Sahu. Biodiesel vs diesel: A race for the future, Energy sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. eff, 39 (14), 1453–1460. (2017).

Swarup Kumar Nayak. Purna Chandra Mishra. Emission characteristics of jatropha oil blends using waste wood producer gas. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 38 (14), 2153–2160 (2016).

Swarup Kumar Nayak. Purna Chandra Mishra. & Gyana Ranjan behera. Characterization of coconut shell imitatived producer gas in a diesel engine. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 39 (16), 1718–1724 (2017).

Swarup Kumar Nayak. Purna Chandra Mishra. Emission characteristics of diesel fuel composed of linseed oil (Linum Usitatissium) blends utilizing rice husk producer gas. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 38 (14), 2001–2008 (2016).

Tondo, W. L. et al. <b > Biodiesel as fuel for boilers</b >. Acta Scientiarum Technol. 39 (5), 609. https://doi.org/10.4025/actascitechnol.v39i5.29501 (2017).

Jindal, S., Nandwana, B. P., Rathore, N. S. & Vashistha, V. Experimental investigation of the effect of compression ratio and injection pressure in a direct injection diesel engine running on Jatropha Methyl ester. Appl. Therm. Eng. 30 (5), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.10.004 (2010).

Erdiwansyah., Mamat, R. et al. M.H. Effects of Diesel-Biodiesel Blends in Diesel Engine Single Cylinder on the Emission Characteristic. MATEC Web of Conferences. 225, 01013; (2018). https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201822501013

Maawa, W. N., Mamat, R., Najafi, G., Ali, O. & Majeed., Aziz, A. Engine performance and emission of compression ignition engine fuelled with emulsified biodiesel-water. IOP Conf. Series: Mat. Sci. Eng. 100, 012061. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/100/1/012061 (2015).

Harish, H., Mohanraj, Y., Younus & Nachketh. & Extraction of biodiesel from fish fat and experimental evaluation of performance and emission characteristics in diesel engine. Dogo Rang Res. J. 10 (8), 117–124 (2020).

Ghassan, F., Smaisim., N., Manikanda Prabu., Senthilkumar, A. P., Azher, M. & Abed Synthesis and thermodynamic analysis of biodiesel from fish processing waste using nano magnetic catalyst. Case Stu Ther. Eng. 35, 102–115 (2022).

Sahoo, P. K. & Das, L. M. Combustion analysis of Jatropha, Karanja and Polanga based biodiesel as fuel in a diesel engine. Fuel 88 (6), 994–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2008.11.012 (2009).

Rajan., K., Senthilkumar, K. R. & M. Prabhahar. & Experimental studies on the performance, emission and combustion characteristics of a biodiesel-fuelled (Pongamia Methyl ester) diesel engine with diethyl ether as an oxygenated fuel additive. Int. J. Amb Ener. 37 (5), 439–445 (2016).

Nisar, N. et al. Mazhar. Brassicaceae family oil Methyl esters blended with ultra-low sulphur diesel fuel (ULSD): comparison of fuel properties with fuel standards. Rene Ener. 117, 393–403 (2018).

Huang, H. et al. Combustion performance and emission characteristics of a diesel engine under low-temperature combustion of pine oil-diesel blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 128, 317–326 (2016).

Nagaraja, S., Sooryaprakash, K. & Sudhakaran, R. Investigate the effect of compression ratio over the performance and emission characteristics of variable compression ratio engine fueled with preheated palm Oil - Diesel blends. Proce Ear Planet. Sci. 11, 393–401 (2015).

Cheralathan, M. & Balaji. & Experimental investigation of varying the fuel injection pressure in a direct injection diesel engine fuelled with Methyl ester of Neem oil. Int. J. Ambi Energy. 38 (4), 356–364 (2017).

Pasha, Y., Shrinivasa, U. & Swamy, D. R. Experimental analysis of fuel properties and performance analysis of diesel engine with esterified castor oil blended with gasoline. Mat. Tod Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.331 (2020).

Yoon, S. K., Ge, J. C. & Choi, N. J. Influence of fuel injection pressure on the emissions characteristics and engine performance in a CRDI diesel engine fueled with palm biodiesel blends. Energies 12 (20), 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12203837 (2019).

Younus Pasha, Shrinivasa, U., Swamy., D. R., Muzzamil Ahamed, S. & Harish, H. Investigation of performance parameters combustion and emission characteristics of compression ignition engine fuelled with pongamia Methyl ester-gasoline blend. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2021.1929578 (2021).

Anmesh Kumar Srivastava. Shyam Lal Soni., Dilip Sharma. & Narayan Lal Jain. Effect of injection pressure on performance, emission, and combustion characteristics of diesel–acetylene-fuelled single cylinder stationary CI engine. Environ. Sci. Poll.Res.18; (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-1070-3

Sivalakshmi, S. & Balusamy, T. Influence of ethanol addition on a diesel engine fuelled with Neem oil Methyl ester. Int. J. Gr Energy. 9 (3), 218–228 (2012).

Şen, M. The effect of the injection pressure on single cylinder diesel engine fueled with propanol–diesel blend. Fuel 254, 115617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2019.115617 (2019).

Harish., H., Rajanna., S., Prakash., G. S., Ramachandra, K. & Srikanth, H. V. Experimental investigation of effect of injections parameters on stationary diesel engine fuel with the Methyl ester of waste vegetable oil. J. Green. Eng. 10 (11), 12195–12215 (2020).

Can, O., Çelikten, I. & Usta, N. Effects of ethanol addition on performance and emissions of a turbocharged indirect injection diesel engine running at different injection pressures. Energ. Convers. Manage. 45 (15–16), 2429–2440 (2004).

Kandasamy, M. & Palanisamy, G. The effect of Bio-Fuel blends and fuel injection pressure on diesel engine emission for sustainable environment. Amer J. Environ. Sci. 7 (4), 377–382 (2011).

Channapattana., S. V., Abhay, A., Pawar., Prashant, G. & Kamble Effect of Injection Pressure on the Performance and Emission Characteristics of VCR engine using Honne Biodiesel as a Fuel. Mat. Tod. Proc. 2, 1316–1325, (2015).

Harish, H., Rajanna, S., Prakash, G. S. & Srikanth, H. V. The influence of injection timings on performance, emission, and combustion characteristics of compression ignition engine fueled with milk scum oil biodiesel. Energy Sources A: Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1859007 (2020).

Choi, C. Y. & Reitz, R. D. An experimental study on the effects of oxygenated fuel blends and multiple injection strategies on DI diesel engine emissions. Fuel 78 (11), 1303–1317 (1999).

Punith Kumar, S. V. & Harish, H. Experimental investigation on injection parameters by varying compression ratio using fish oil biodiesel in diesel engine. Int. J. Ignited Minds. 2 (1), 1333–1341 (2015).

Harish., H., Rajanna., S., Prakash, G. S. & Ahamed, S. M. Extraction of biodiesel from tung seed oil and evaluating the performance and emission studies on 4-stroke CI engine. Mat. Tod. Proc. 46 (10), 4869–4877, (2021).

Lassoued., I., Seif, C. B. R. S. & Houssem, E. H. Y. El Fetni. Effect of fuel injection pressure on performance and emission characteristics of a compression ignition direct injection engine fuelled with waste cooking oil biodiesel mixture. Int. J. Renew. Ener Res. 8 (4), (2018).

Rodica Niculescu. Adrian clenci. & victor Iorga Siman. Review on the use of Diesel-Biodiesel-Alcohol blends in compression ignition engines. Energies 12, 1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12071194 (2019).

Nitin Shrivastava & Varma, S. N. Mukesh pandey. Experimental investigation of diesel engine using EGR and fuelled with Karanja oil Methyl ester. Int. J. Sust Eng. 6 (4), 307–315 (2013).

Jose Rodriguez, F. & Juan Jose Hernandez. Selection of Blends of Diesel Fuel and Advanced Biofuels Based on Their Physical and Thermochemical Properties. Energies. 12, ; (2034). https://doi.org/10.3390/en12112034 (2019).

Canakci, M., Sayin, C., Ozsezen, A. N. & Turkcan, A. Effect of injection pressure on the combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of a diesel engine fueled with methanol-blended diesel fuel. Energy Fuels. 23 (6), 2908–2920 (2009).

Abed, K. A., Gad, M. S., El Morsi, A. K., Sayed, M. M. & Elyazeed, S. Abu. Effect of biodiesel fuels on diesel engine emissions. Egypt. J. Petro. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpe.2019.03.001 (2019).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge co-author Dr G Padmanaban who passed away.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G P: Experimentation & InvestigationA B: Conceptualization & MethodologyG F: Formulation & CalculationM N: Interpretation of results & Report writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Basem, A., Smaisim, G.F. & Prabu, N.M. Investigation on diesel engine with biodiesel – gasoline fuel blends at a distinguished injection pressure. Sci Rep 15, 17812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91163-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91163-0