Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among middle-aged and elderly individuals may influence the subsequent occurrence of chronic kidney disease (CKD). We aim to investigate the association between ACEs and CKD among the middle-aged and elderly populations in China. The prospective cohort longitudinal study examined baseline data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) from June 1 to December 31, 2014. Subsequent follow-up surveys were conducted in 2015, 2018, and 2020. The study population consisted of 4063 participants aged at least 45 years, who had CKD data and information on the 16 complete ACEs indicators included in this study. Utilizing correlation analysis to explore the relationship between CKD and the total score of ACEs, as well as the three dimensions (Conventional ACEs, Expanded ACEs, and New ACEs), along with specific items. The correlation between individual ACEs, disease-related factors, and CKD was examined using binary logistic regression models. Valuable diagnostic factors were then identified through the use of ROC curves. A Cox proportional hazards regression model, with age as the timescale and ACEs groups as covariates, was established to investigate the relationship between age-related CKD occurrence and ACE groups as individuals aged. Among the 4063 participants included in the analysis, in patients with CKD, the male proportion is 85 (64.9%), and the female proportion is 46 (35.1%). Of the participants, 2332 experienced at least two Conventional ACEs, 3786 experienced at least two Expanded ACEs, and 2774 experienced at least one New ACE. Factors influencing the occurrence of CKD in participants included Conventional ACEs 5 (OR 1.742; 95% CI 1.115–2.721; P = 0.015), Conventional ACEs 6 (OR 1.581; 95% CI 1.024–2.442; P = 0.039), Conventional ACEs 9 (OR 2.190; 95% CI 1.288–3.725; P = 0.004), Expanded ACEs 3 (OR 0.195; 95% CI 0.085–0.444; P < 0.001), memory-related disease (OR 3.297; 95% CI 1.140–9.538; P = 0.028), dyslipidemia (OR 2.536; 95% CI 1.521–4.230; P < 0.001), cancer (OR 6.369; 95% CI 2.464–16.461; P < 0.001), chronic lung disease (OR 2.261; 95% CI 1.091–4.684; P = 0.028), and liver disease (OR 3.050; 95% CI 1.432–6.497; P = 0.004). These three models showed significant statistical differences in CKD, the Conventional ACEs, and the New ACEs. In Model 1, 2, and 3, the risk was higher for individuals exposed to the Conventional ACEs group, indicating an increased likelihood of developing CKD, the risk was lower for individuals exposed to the New ACEs group, suggesting a reduced likelihood of developing CKD. ROC curve analysis of these variables showed that CA5, CA6, CA9, dyslipidemia had significant diagnostic value for the occurrence of CKD. The accuracy of diagnosis was CA5 (57.0%), CA6 (58.3%), CA9 (59.4%), and dyslipidemia (59.8%). This study, through longitudinal investigation, has identified potential links between ACEs and disease-related factors with CKD. These findings can still provide assistance to clinicians and public health administrators, helping them understand the association between ACEs and CKD, and offering theoretical support for their clinical decision-making or development of public health policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the escalating global challenge of population aging has become increasingly severe. China, as one of the world’s most populous nations, is experiencing a particularly conspicuous manifestation of demographic aging. According to data published by the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics in 2019, the population aged 65 and above constitutes 11.9% of the total population in China. Furthermore, projections indicate that by the year 2025, the population aged 60 and above is expected to reach 498 million1. Chronic kidney disease (CKD), a prevalent ailment among the elderly, is defined as sustained renal structural or functional abnormalities persisting for three months or more, exerting adverse effects on an individual’s health. A glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or proteinuria equal to or exceeding 30 mg/24 h serves as diagnostic criteria indicative of renal impairment2. According to the 2019 Sixth China Chronic Disease and Risk Factors Survey, the prevalence of CKD in Chinese adults has decreased by nearly 30% compared to the past decade. However, the number of CKD patients requiring dialysis has witnessed an increase, projected to reach 629.67 per million population by 20253,4. In addition to affecting middle-aged and elderly individuals negatively, this burdens the nation’s healthcare system significantly.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as a series of intense stressors occurring in the early stages of a young person’s life5. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States explicitly delineate ACEs to encompass all forms of abuse and potential traumatic events that occurred before the age of 186. Early ACEs primarily encompass three major categories: abuse, neglect, and dysfunctional family dynamics, further subdivided into ten specific situations. As scholarly research in this field advances, the study found that if only conventional ACEs are included, the ACEs exposure of 14.2% of middle-aged and elderly people will be underestimated7. Therefore, scholars have augmented and refined the Conventional ACEs concept by incorporating additional categories such as peer bullying, insecure neighborhood relationships, parental death, among others, giving rise to the Expanded ACEs and the New ACEs8.

ACEs have been demonstrated to exert lasting effects on the health of adults, elevating the risk of premature mortality9,10,11. A systematic review on the association between ACEs and health outcomes reveals that, during the past 30 years, the majority of studies have predominantly concentrated on the correlation between ACEs and social-psychological aspects, with a relatively limited exploration of specific health outcomes12. In addition, some studies have explored the relationship between ACEs and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. The results showed that there is a correlation between the two. That is, patients with ACEs have a higher risk of developing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases9. Currently, the research regarding the relationship between CKD and ACEs is limited. Although literature suggests a higher probability of CKD among individuals who have experienced ACEs9,13, existing studies lack clarity on the correlation between ACEs, demographic factors, individual health status, and CKD. The inclusion of ACEs elements is also relatively restricted, with research predominantly focused on developed countries, leaving a scarcity of studies examining this association in developing countries where higher ACEs prevalence may exist.

In this study, we utilized data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), collecting information on 16 indicators of ACEs among middle-aged and elderly individuals in China. Through a longitudinal investigation, we identified the potential link between ACEs and CKD, investigating whether this correlation is influenced by demographic factors and health status.

Materials and methods

Research design and study population

Study data come from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which is a nationally representative survey of Chinese adults age 45 and older. It covers 28 provinces, 150 counties, and 450 communities (villages) across mainland China14. This research utilized a sampling design that involved four stages of stratification and made use of data collected during the baseline survey of CHARLS, which took place from June 1 to December 31, 2014. Subsequent follow-up surveys were conducted in 2015, 2018, and 2020. All living respondents were asked about adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the 2014 life history survey. A data analysis was conducted between January 1 and January 30, 2024 for this study. We have obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at Peking University, and all participants have provided written informed consent15. In accordance with the ethical policies and procedures of the London School of Economics, the current study does not require ethical approval or informed consent as it involves secondary analysis of an existing dataset. Reporting guidelines for Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) are followed in this study.

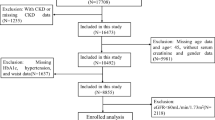

A total of 11,426 participants aged at least 45 years were included, having completed the survey questionnaire in 2014. According to study criteria, 6406 participants were excluded due to the absence of CKD and relevant covariate information, while an additional 957 participants were excluded due to age < 45 years. Ultimately, 4063 participants were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Operational definition of ACEs

In the life history survey conducted in 2014, information on adverse childhood experiences before the age of 17 was collected through face-to-face interviews. Based on prior research, we captured 16 ACE indicators, including 9 Conventional ACE indicators, 3 Expanded ACE indicators and 4 New ACE indicators. “Supplementary Materials” provides detailed definitions for each ACE indicator. Each ACE indicator was dichotomously coded, with 0 indicating absence and 1 indicating presence. To determine the cumulative ACE score, we summed up the occurrences of ACEs in each dimension. According to the frequency of ACEs in each dimension included, participants were divided into three groups based on the cumulative scores for three ACE dimensions (i.e., 0, 1, and ≥ 2 Conventional ACEs; 0, 1, and ≥ 2 Expanded ACEs; and 0, 1, and ≥ 2 New ACEs).

The operational definition of CKD

According to the way CHARLS collects information on the participants’ CKD status, CKD diagnosis was based on self-report by physicians, using the question, "Have you been told by a doctor that you have kidney disease?" If an individual or their proxy respondent provided an affirmative answer, the individual would be classified as having experienced CKD for the first time in their life (excluding tumors or cancer).

Covariates

CHARLS surveyed participants or their proxies using filtered questionnaires, and demographic and lifestyle characteristics were collected through face-to-face questionnaires, including age, gender, residential area, education level, and the presence of other chronic conditions (hypertension, digestive disease, memory-related disease, asthma, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, liver disease, heart disease, stroke). To avoid recall bias caused by incomplete memory for participants, their spouses or caregivers answer the related questions on their behalf.

Statistic analysis

A normal distribution is used to express quantitative data using mean and standard deviation. Utilizing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare differences among the three groups (Conventional ACEs, Expanded ACEs and New ACEs). Qualitative data was represented in percentages. Baseline characteristics among different ACEs groups were compared using ANOVA for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. The presence of CKD was analyzed as a binary variable. Changes in CKD over time were assessed by counting the number of individuals reporting CKD at follow-up periods (2015, 2018, and 2020), described in relation to various forms of adverse childhood experiences, and compared using ANOVA. Correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between CKD and the total ACE scores, as well as the three dimensions (Conventional ACEs, Expanded ACEs, and New ACEs), and their specific items. We further analyzed the longitudinal data from 2014 to 2020 using logistic regression models to examine the relationship between each ACE item and CKD, presenting odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Additionally, we established Cox proportional hazards regression models, considering age as the time scale and stratifying by ACEs groups, to assess hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Model 1 was unadjusted for confounding factors, Model 2 was adjusted for gender, age, residence, and education level, while Model 3 included adjustments for hypertension, digestive disease, memory-related disease, asthma, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, liver disease, heart disease, and stroke. All statistical analyses were performed at a significance level of 0.05, and the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 and R Studio (version 4.0.4). Analysis results with P < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

Results

Among the 4063 participants included in the analysis, in patients with CKD, the male proportion is 85 (64.9%), and the female proportion is 46 (35.1%). The age group of 45–59 years old accounts for 59 (45.0%), and the age group of 60 years and older accounts for 72 (55.0%). As shown in Table 1, ACEs were categorized into three groups: Conventional ACEs, Expanded ACEs, and New ACEs. A total of 2332 participants experienced at least two Conventional ACEs, 3786 participants experienced at least two Expanded ACEs, and 2774 participants experienced at least one New ACE. The results of this study revealed that 3876 individuals, accounting for 95% of the total participants, had experienced three or more ACEs. Moreover, 52.9% had experienced five or more ACEs. The majority of participants resided in rural areas, and the educational level was predominantly concentrated at the primary school level or below. Changes in the prevalence of hypertension, digestive disease, memory-related disease, asthma, dyslipidemia, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, liver disease, heart disease and stroke were comparable across the three ACEs groups (see Table 1).

In the analysis of the association between CKD and ACEs total score, three dimensions (Conventional ACEs, Expanded ACEs, and New ACEs) and specific items, we observed a positive correlation between CKD and ACEs total score, total Conventional ACE scores, as well as Conventional ACE items 2, 5, 6, 8, 9 and Expanded ACEs 2. These correlations were statistically significant. Additionally, there was a negative correlation between CKD and item 3 in the Expanded ACEs category, and this correlation was statistically significant (see Table 2).

Before conducting binary logistic regression analysis, variables were selected through independent samples t-tests, chi-square tests, and collinearity diagnostics. Then, the selected independent variables were included in the binary logistic regression analysis. The results indicated that Conventional ACEs 5, Conventional ACEs 6, Conventional ACEs 9, memory-related disease, dyslipidemia, cancer, chronic lung disease and liver disease were risk factors influencing whether participants had CKD. Expanded ACEs 3 was protective factor influencing participants had CKD (see Table 3).

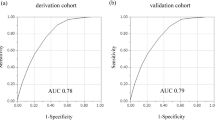

According to the results of binary logistic regression, CA5, CA6, CA9, EA3, memory-related disease, dyslipidemia, cancer, chronic lung disease and liver disease were influencing factors in subjects with CKD. Therefore, further ROC curve analysis of these variables showed that CA5, CA6, CA9 and dyslipidemia had significant diagnostic value for the occurrence of CKD. The accuracy of diagnosis was CA5 (57.0%), CA6 (58.3%), CA9 (59.4%) and dyslipidemia (59.8%) (see Fig. 2 and Table 4).

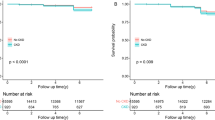

Table 5 displays the cross-sectional association between CKD and ACEs groups at baseline in 2014 as participants’ age. The results indicate that, as participants’ age, the three models showed no statistical significance with the Expanded ACEs group, while they exhibited statistical significance with both the Conventional ACEs group and the New ACEs group. Furthermore, it can be observed that, across model 1, 2 and 3, there is a higher risk associated with the Conventional ACEs group, suggesting that participants exposed to the Conventional ACEs group have a higher risk of developing CKD. Conversely, the risk is lower between models 1, 2 and 3 and the New ACEs group, indicating a lower risk of CKD among participants exposed to the New ACEs group. All three models show no statistical significance with the Expanded ACEs group.

Discussion

As far as we known, this study represents the first longitudinal investigation utilizing nationally representative data to examine the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) among the Chinese population aged 45 and above. The study identified a relationship between ACEs and CKD incidence. Among the three sets of 16 categories of ACEs, Conventional ACEs 5 (During the years you were growing up, which one of the followings did your female/male guardian ever have?), Conventional ACEs 6 (Have your father/mother ever beat up your mother/father?), Conventional ACEs 9 (When you were growing up, did your female/male guardian ever hit you?), and Expanded ACEs 3 (Was it safe being out alone at night in the neighborhood where you lived as a child?) were identified as major factors influencing the occurrence of CKD. Additionally, CKD incidence was associated with participants’ memory-related disease, dyslipidemia, cancer, chronic lung disease and liver disease. ROC curve analysis of these variables revealed significant diagnostic value for the occurrence of CKD in Conventional ACEs 5, Conventional ACEs 6, Conventional ACEs 9, and dyslipidemia.

There is limited research exploring the relationship between ACEs and CKD. Despite scholars finding that ACEs increase the risk of chronic diseases in middle-aged and elderly individuals, most studies do not encompass kidney diseases16,17. Furthermore, when chronic diseases are investigated, they are often studied collectively without subgroup analysis for different disease types18,19. This approach results in considerable confounding factors, making it challenging to elucidate the association between CKD and ACEs. A cross-sectional study conducted by Merrick and colleagues across 25 states in the United States revealed that ACEs are a risk factor for the occurrence of CKD20. ACEs have been shown to be a risk factor for late-onset chronic kidney disease in a large prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom7, but they only included Conventional ACE items. Evidence suggests that Conventional ACEs may no longer adequately capture the diverse childhood adversities experienced by different populations, necessitating the addition of new items for supplementation21,22. Therefore, this study incorporates both Expanded and New ACEs categories to better measure the occurrence of ACEs in the study population. Additionally, these studies have primarily focused on developed countries, and there is a lack of research investigating such associations in developing countries where the prevalence of ACEs is higher.

It appears from a considerable body of evidence that the impact of ACEs on CKD is physiologically plausible. Firstly, it has been established that early childhood adverse experiences have negative effects on the nervous, endocrine, and metabolic systems. These effects may stem from alterations within the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the autonomic nervous system23. Repeated exposure to ACEs can lead to dysregulation of the stress system, diminished immune function, and an increase in inflammatory markers24,25. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 further contribute to increased susceptibility to chronic inflammation7,26, thereby raising the risk of individuals developing CKD. Furthermore, for individuals already affected by kidney disease, the prolonged stress response triggered by ACEs increases the risk of premature mortality27.

The current study’s findings revealed a positive association between exposure to Conventional ACEs and an elevated risk of CKD. Specifically, it was observed that individuals who had endured such Conventional ACEs were at a heightened risk of developing CKD. This may be related to the participants’ prolonged exposure to stress during childhood, which increased their susceptibility to chronic inflammation and, thus, their likelihood of developing CKD7,26. Expanded ACEs 3 was negatively correlated with the risk of CKD. That is, participants who experienced Expanded ACEs 3 had a reduced risk of developing CKD. The findings of this study indicate that unsafe neighborhood serve as a protective factor for CKD, which contradicts the view of Liu et al. that unsafe neighborhood are significantly associated with an increased number of chronic diseases28. A possible reason for this discrepancy is that individuals who live in unsafe environments for an extended period may develop stronger stress tolerance and adaptability, known as “adversarial resilience,” thereby reducing their risk of CKD by enhancing psychological resilience and coping strategies. These individuals may prioritize health management and adopt more proactive lifestyles. The specific reasons remain unclear, but this discovery suggests that we need to delve deeper into the impact of unsafe neighborhood on health, particularly in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Further research in this area is necessary to better understand the causal relationship between unsafe neighborhood and CKD risk and to explore other potential mediating variables or moderating factors.

In this study, Conventional ACEs 5, Conventional ACEs 6, and Conventional ACEs 9 were found to be the main influencing factors on the development of CKD, and these three ACEs’ factors can be broadly categorized into two broad categories: domestic violence and caregiver’s adverse habits. Studies have shown that exposure to domestic violence during childhood can have a significant negative impact on adult health status. This type of violence not only affects the psychological well-being of the child but also has direct physiological consequences. For instance, it can lead to chronic stress responses within the body, which in turn disrupt the normal functioning of the HPA axis23. This disruption can cause hormonal imbalances, such as increased levels of cortisol, which have been associated with a range of health issues including increased blood pressure and altered glucose metabolism. Moreover, children who experience domestic violence are more likely to develop maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as emotional eating or reduced physical activity levels29. These behaviors can further exacerbate the risk of developing obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, all of which are significant risk factors for CKD. Studies have also found that living with a caregiver who has a history of alcohol and drug abuse increases the likelihood of risky behaviors and chronic disease rates in adulthood. Such caregivers are likely to provide an unstable and chaotic living environment. This not only exposes children to potential physical harm but also leads to emotional neglect. As a consequence, children may develop maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as substance abuse themselves or engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors30. These two aspects of ACEs are highly likely to cause varying degrees of damage to the metabolic, cardiovascular, immune and nervous systems. This early damage will make children face many severe health challenges in their future lives, thereby greatly increasing the probability of developing CKD31.

The results of this study revealed that 3876 individuals, accounting for 95% of the total participants, had experienced three or more ACEs. Moreover, 52.9% had experienced five or more ACEs, a considerably higher proportion compared to other developing countries. For instance, in Saudi Arabia, 41.7% of the study population reported exposure to three or more ACEs16, and in the Philippines, only 9% of the population was reported to be exposed to four or more ACEs32. Developed countries showed lower percentages, with 37% of participants in Canada having experienced two or more ACEs32, and a survey in the United States involving 29,212 participants indicating that 59% had experienced at least one ACE33. The underlying reasons for this might be attributed to the relatively older age of the study participants and the less developed economic conditions in China during the 1970s and 1980s34, during this period, there was a lack of formulated public policies and widespread dissemination of relevant concepts. Particularly in rural areas, where there was an encouragement of higher birth rates35, the attention towards the mental and physical well-being of adolescents was insufficient. Furthermore, the richness of the ACE items included in this study, compared to other research, has to some extent increased the prevalence rate. Moreover, among participants in China who experienced ACEs, the educational attainment is predominantly concentrated at the primary school level and below. In contrast, research reports from Saudi Arabia and the United Kingdom indicate that the cultural levels of their surveyed populations are more concentrated at the college or university levels7,16. This could be due to the inclusion of middle-aged and elderly participants aged 45 and above in this study, during a time when compulsory education had not yet been universally implemented in China.

Strengths and limitations

In this study, data from a large, nationally representative longitudinal survey were analyzed. According to our knowledge, the relationship between ACEs and CKD has never been studied longitudinally before among individuals aged 45 and above in developing countries. The study included a large number of participants, and the samples are well representative. Three models were established using the Cox proportional hazards regression model to assess hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Additionally, the study included a total of 16 items, encompassing Conventional ACEs, Expanded ACEs, and New ACEs, providing a more comprehensive measurement of the occurrence of ACEs in the population of developing countries.

It is important to note that our study has some limitations. Firstly, the investigation of ACEs was not based on prospective research conducted during the subjects’ childhood but rather obtained through retrospective descriptions, introducing potential recall bias. Secondly, despite our efforts to adjust for confounding factors, there are still unconsidered confounders in this study, such as socioeconomic characteristics of the population. Thirdly, the study’s data is solely derived from a Chinese database, and the conclusions drawn may not be generalized to other countries. This study still has limitations, but the findings can still be helpful to clinical practitioners, public health administrators, etc., in understanding the association between ACEs and CKD, providing theoretical support for their clinical decision-making or public health policy formulation.

Conclusions

In this study, Conventional ACEs 5, Conventional ACEs 6 and Conventional ACEs 9 were risk factors influencing whether participants had CKD. Expanded ACEs 3 was protective factor influencing participants had CKD. Additionally, chronic diseases such as memory-related disease, dyslipidemia, cancer etc., also influence the onset of CKD. As a result of this study, we contribute further to the understanding of the impact of ACEs on population health. Our research emphasizes the importance of addressing ACEs globally, advocating for the well-being of adolescents, and reducing the incidence of CKD in older adults, thereby lessening the burden of chronic diseases and enhancing overall quality of life.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), data can be accessed via http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of CHARLS research team. The authors had no special access privileges in accessing data from CHARLS.

References

Zhenwu, Z., Jiaju, C. & Long, L. Future trends of China’s population and aging: 2015–2100. Popul. Res. 41(04), 60–71 (2017).

Charles, C. & Ferris, A. H. Chronic kidney disease. Prim. Care 47(4), 585–595. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.66.S1.3 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: Results from the sixth china chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. JAMA Intern. Med. 183(4), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.6817 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Estimation of prevalence of kidney disease treated with dialysis in China: A study of insurance claims data. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 77(6), 889–897. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.11.021 (2021).

Gette, J. A. et al. Modeling the adverse childhood experiences questionnaire-international version. Child Maltreat. 27(4), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211043122 (2022).

Merrick, M. T. et al. Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 69, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016 (2017).

Zhang, K. et al. Self-reported childhood adversity, unhealthy lifestyle and risk of new-onset chronic kidney disease in later life: A prospective cohort study. Soc. Sci. Med. 341, 116510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.116510 (2024).

Zimo, Z. The Correlation Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Sleep Quality in College Students: The Mediating Effect of Early Maladaptive Schemas (Beihua University, 2022).

Austin, A. Association of adverse childhood experiences with life course health and development. N. C. Med. J. 79(2), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.18043/ncm.79.2.99 (2018).

Campbell, J. A., Walker, R. J. & Egede, L. E. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am. J. Prev. Med. 50(3), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.07.022 (2016).

Marie-Mitchell, A. & Kostolansky, R. A systematic review of trials to improve child outcomes associated with adverse childhood experiences. Am. J. Prev. Med. 56(5), 756–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.030 (2019).

Petruccelli, K., Davis, J. & Berman, T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 97, 104127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127 (2019).

Hege, A. et al. Adverse childhood experiences among adults in North Carolina, USA: Influences on risk factors for poor health across the lifespan and intergenerational implications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228548 (2020).

Zoccali, C. et al. The systemic nature of CKD. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13(6), 344–358. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2017.52 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. Cohort profile: The China health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203 (2014).

Almuneef, M. et al. Adverse childhood experiences, chronic diseases, and risky health behaviors in Saudi Arabian adults: A pilot study. Child Abuse Negl. 38(11), 1787–1793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.003 (2014).

Njoroge, A. et al. Assessment of adverse childhood experiences in the south bronx on the risk of developing chronic disease as adults. Cureus 15(8), e43078. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.43078 (2023).

Li, J. et al. A retrospective cohort study of the effects of the adverse childhood experience on chronic diseases of middle-aged and elderly. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 42(10), 1804–1808. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20201223-01435 (2021).

Yudong, X., Ya, F. & Yanbing, Z. The incidence of adverse childhood experiences among residents over 45 years old and health effects in China. Chin. J. Health Stat. 40(3), 341–344 (2023).

Merrick, M. T. et al. Vital signs: Estimated proportion of adult health problems attributable to adverse childhood experiences and implications for prevention—25 states, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 68(44), 999–1005. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6844e1 (2019).

Lin, L. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and subsequent chronic diseases among middle-aged or older adults in China and associations with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 4(10), e2130143. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30143 (2021).

Finkelhor, D. et al. Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. JAMA Pediatr. 167(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.420 (2013).

Berens, A. E., Jensen, S. & Nelson, C. R. Biological embedding of childhood adversity: From physiological mechanisms to clinical implications. BMC Med. 15(1), 135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0895-4 (2017).

Deighton, S. et al. Biomarkers of adverse childhood experiences: A scoping review. Psychiatry Res. 269, 719–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.097 (2018).

Audage, N. C. & Middlebrooks, J. S. The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. Atlanta 8, 1–6 (2008).

Hostinar, C. E. et al. Additive contributions of childhood adversity and recent stressors to inflammation at midlife: Findings from the MIDUS study. Dev. Psychol. 51(11), 1630–1644. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000049 (2015).

Ozieh, M. N. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and decreased renal function: Impact on all-cause mortality in US adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 59(2), e49–e57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.005 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Adverse childhood experiences and multimorbidity among middle-aged and older adults: Evidence from China. Child Abuse Negl. 7(158), 107100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2024.107100 (2024).

Gordon, J. B. The importance of child abuse and neglect in adult medicine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 211, 173268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2021.173268 (2021).

Chang, X., Jiang, X., Mkandarwire, T. & Shen, M. Associations between adverse childhood experiences and health outcomes in adults aged 18–59 years. PLoS One 14(2), e0211850. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211850 (2019).

Blane, D., Kelly-Irving, M., Errico, A., Bartley, M. & Montgomery, S. Social-biological transitions: How does the social become biological?. Longitud. Life Course Stud. 4(2), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.14301/llcs.v4i2.236 (2013).

Chartier, M. J., Walker, J. R. & Naimark, B. Separate and cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences in predicting adult health and health care utilization. Child Abuse Negl. 34(6), 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.020 (2010).

Bynum, L. et al. Adverse childhood experiences reported by adults—Five states, 2009. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 59(49), 1609–1613 (2010).

Li, T. & Yan, Y. Differences in mortality by region in china since the 1980s and their evolution: The staged synergy between medical investment and socio-economic development. Popul. Res. 47(4), 35–50 (2023).

Feng, L. Change of fertility rate and the analysis of social and economic factors in China in 1980s. Chin. J. Popul. Sci. 01, 42–47 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) for providing the valuable data used in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, [Grant/Award Number: 82272926]; Promoting scientific research cooperation and high-level talent training projects with Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Latin America of the National Scholarship Foundation, [Grant/Award Number: (2022) 1007].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ziyi Shen:Topic selection, manuscript composition Chengcheng Li:Data analysis, manuscript composition Yan Fang:Figure creation, manuscript composition Hongxu Chen:Data analysis Yongxia Song:Manuscript revision Junling Cui:Figure creation Xin Luo:manuscript composition Yanchang Liu:Data analysis Fei Zhong:Article review Jingfang Hong:Article review and correction.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, Z., Li, C., Fang, Y. et al. Association between adverse childhood experiences with chronic kidney diseases in middle-aged and older adults in mainland China. Sci Rep 15, 6469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91232-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91232-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Impact of adverse childhood experiences on kidney health

Pediatric Nephrology (2025)