Abstract

The magnetic properties of amorphous thin films are shaped by inherent composition variations and magnetic proximity effects. Their magnetic properties can be tuned precisely with composition over a continuous range and their high resistance reduces shunting in spintronic systems. We examine the static and dynamic magnetic properties of amorphous magnetic thin films of Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x in the range \(0.60\le x<0.87\), with and without a purposely modulated composition. The Gilbert damping is very low but increases dramatically with decreasing Co content. Damping is also studied in a CoAlZr multilayer with alternating intrinsically paramagnetic and ferromagnetic layers, and a film with a continuously modulated composition, both showing low damping. The structural and magnetic depth profiles of the heterostructures are measured with XRR and PNR, where proximity-induced magnetization is observed in the paramagnetic constituents. The enhancement in magnetization and reduction in damping is equivalent to an increase in mean Co content of approximately 3.4 at% and 1.9 at% for the multilayer and continuously modulated film, respectively. The results demonstrate how composition modulations affect the static and dynamic properties of thin films and how the magnetic proximity effect reduces the impact of such variations in composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thin film ferromagnets are central to many device applications, e.g. in data storage1 and spintronics2, as well as in magnonics3. The dynamic magnetic properties, specifically the resonance frequency and magnetization damping, are crucial in these technologies. They determine factors such as switching speed in magnetic random access memory (MRAM) and relaxation to equilibrium. Furthermore, the magnetization damping strongly affects the critical write current in spin-torque MRAM4. It also influences domain wall velocity in racetrack memories5,6 and magnon spin wave velocity and propagation length in magnonic systems3. Equally important to characterizing individual film properties is understanding their interaction with other layers in multilayer structures. These can be interface effects due to interface roughness7, or one of many magnetic coupling effects, such as interlayer exchange8, dipole-dipole coupling, or the magnetic proximity effect9. In this paper, we characterize the dynamic magnetic properties of amorphous ferromagnetic thin films, and we study multilayers and structures with graded compositions where proximity effects play an important role.

Amorphous metal magnets are most widely known for their soft magnetic properties, including low coercivity and low hysteretic losses10. They also have higher resistivity than their crystalline metal counterparts, which reduces eddy currents11. Amorphous magnets can therefore be a great alternative for high-frequency applications in cases where eddy current suppression is of importance e.g. in bulk materials12. Additionally, ferromagnets (FM) with high resistivity are useful for reducing shunting currents in spin-orbit torque (SOT) switching devices13. Moreover, a general advantage of working with amorphous materials is that their composition can be tuned over a large continuous range without phase segregation or defect formation14. This facilitates precise control over the magnetic properties and great flexibility in the materials which can be combined in both alloys and heterostructures. It also opens up the possibility of realizing graded composition materials. Such graded composition magnetic systems have seen a surge in interest lately with potential applications including exchange-spring media with graded anisotropy15,16,17 and field-free SOT switching through a gradient-driven Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction18. However, the impact of a graded composition on magnetization dynamics has not been explored much.

Thin film amorphous alloys have another unique property in that they possess inherent spatial variations in composition. FeZr alloys grown by magnetron sputtering have been shown to have a spatial variation in composition on the few-nanometer length scale, which was measured by atom probe tomography19. Similar local variations in composition have also been inferred in amorphous Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x films14. These results imply that the composition of an amorphous alloy is more accurately described by a composition distribution with a certain mean composition and width, over a characteristic spatial length scale. The length scale of the variation has not been determined in Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x but is expected to be of the same order of magnitude as in the FeZr case, due to the similarity of the two systems and the synthesis procedures. Since the magnetic properties of both alloys are strongly dependent on composition, the spatial variation in composition can result in a corresponding spatial variation in magnetic properties such as the Curie temperature \(T_c\) and magnetic anisotropy14,19. Amorphous alloys can therefore be considered inhomogeneous magnetic systems with magnetic properties that are dependent not only on the mean composition but also on the width and spatial extent of the composition distribution. Since magnetic inhomogeneity has previously been associated with increased magnetic damping, it is important to determine if this is the case in amorphous magnets with inherent composition variations20,21,22.

The magnetic inhomogeneity of amorphous alloys is counteracted by the presence of a strong magnetic proximity effect. The proximity effect refers to when magnetic ordering is induced in a non-magnetic layer by the proximity of a magnetic layer. Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x heterostructures, with alternating layers of high and low Co content, have been shown to display giant magnetic proximity effects where ferromagnetism (FM) or superparamagnetism (SPM) is induced in an intrinsically paramagnetic (PM) layer across an interface with a high-\(T_c\) layer9,23. Polarized neutron reflectivity measurements have shown that the proximity effect smears out the variation in the magnetization across the interface and the induced magnetization extends several nanometers into the intrinsically non-magnetic layer23,24. Such a long-range proximity effect can be expected to reduce the magnetic inhomogeneity resulting from the inherent spatial composition variations in amorphous materials. However, the implications for the dynamic properties are as yet unknown.

Here we study amorphous Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x alloy films with \(0.60\le x<0.87\) (using simply CoAlZr to refer to the material system in general), where the low end of the composition range is PM and the high end is FM. This allows us to map out the dynamic response in a system where the magnetic properties depend strongly on composition and to study the effects of spatial variations in composition in the presence of magnetic proximity effects. This mapping is the first step towards introducing the material system into devices. First, we examine the dynamic magnetic properties of CoAlZr alloys of different mean compositions and how the magnetic inhomogeneity and measuring at temperatures near the Curie temperature affect damping. We then purposely introduce extreme composition modulations in the form of a square-wave modulated cobalt density and a sinusoidally varying cobalt density and examine the impact this has on the damping. The results reveal the potential of amorphous magnets for high-frequency applications and highlight the crucial role of the magnetic proximity effect in reducing magnetic inhomogeneity in structurally inhomogeneous materials.

Results

Structure

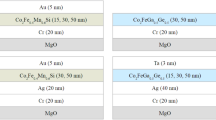

The three types of structures employed in this study are displayed in Fig. 1a. The single-layer (SL) films are Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x, each with a fixed composition. In the continuously modulated composition (CMC) film, the Co content is modulated sinusoidally with depth (z axis) around the mean of \(x=0.725\), with an amplitude of \(A_x = 0.125\) and a wavelength of \(\lambda _z = 100\) Å. This means that the maximum and minimum Co content is \(x_\textrm{max}=0.85\) and \(x_\textrm{min}=0.60\), respectively. The number of periods is 8.5 such that the first and last atomic layers have the same composition and all low-x regions are bounded by high-x regions. The multilayer (ML) is similar to the CMC except that the composition has a square wave modulation, with the same amplitude, phase and wavelength. It is composed of repeated bilayers of compositions \(x=0.85\) and \(x=0.60\) with equal layer thicknesses of 50 Å and a wavelength (i.e. bilayer thickness) of \(\lambda _z = 100\) Å. The ML film begins and ends with an \(x=0.85\) layer, similar to the CMC film.

Film design and structure. (a) Schematics of the three structures studied, the single-layer (left) has a fixed composition, while the composition in the continuously modulated composition (CMC) film (right) varies sinusoidally along the depth of the film z. The multilayer (center) is designed to have the same wavelength and extrema as the CMC. The dark blue and light blue regions are intrinsically ferromagnetic (FM) and paramagnetic (PM), respectively. The AlZr capping and wetting layers are left out of the diagram. (b) XRR measurements of a single-layer (86.5 at%), the CMC and the ML. The measurements are shifted in intensity for clarity. The solid lines are fitted in GenX with a \(\sin ^4\)(\(2\theta\)) weighted FOM below \(1.3 \times 10^{-4}\). The inset displays the scattering length density (SLD), as a function of the depth z, for the CMC and the ML.

X-ray reflectivity measurements of a SL (86.5 at% Co), the ML and the CMC film are displayed in Fig. 1b along with the simulated XRR patterns, fitted using the GenX25 software. The inset of Fig. 1b shows the corresponding scattering length densities (SLD) for the ML and CMC samples. All three films are extremely smooth, with Kiessig interference fringes observed to above \(2\theta =5^{\circ }\). This allows us to extract the total film thickness and the thickness of individual layers reliably. The ML and CMC films display Bragg (or multilayer) peaks due to their periodic density modulation. The wavelength of the CMC and the thickness of the bilayer period in the ML films are designed to be equal, or 100 Å. The vertical dotted line highlights the first Bragg peak and shows that they do have a similar modulation wavelength of approximately 104 Å, as determined by fitting the curves. The ML sample has a series of Bragg peaks, with every second peak almost completely suppressed, as expected for a multilayer with equal layer thicknesses. The XRR pattern for the CMC sample, however, displays only two Bragg peaks. For a pure sinusoidal modulation one would expect a single Bragg peak since we are effectively measuring the Fourier transform of the SLD modulation. The derivation is outlined in the Supplementary Note. The second Bragg peak appears because of a slight thickness mismatch that distorts the sinusoidal modulation such that it is slightly broader at the top and sharper at the bottom (as seen in the inset). This is also the case for the ML sample, although less pronounced. The fitted SLDs of the ML and CMC film also show that there is a slight difference in the wavelength and amplitude.

Static magnetic properties

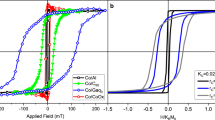

Magnetic hysteresis loops, measured by VSM along the easy axis direction of two single-layers (86.5 and 60.0 at% Co), the ML and the CMC, are displayed in Fig. 2a. CoAlZr alloys are known to be very soft magnets and this is observed in all three FM films, which have coercivities below 0.5 mT. The hysteresis loops of the 86.6% and CMC samples are square, indicating that the magnetization of the entire film switches abruptly by nucleation of a domain wall that sweeps across the film. The ML displays a step that is due to domain structure, where different parts of the film switch at slightly different fields. This was confirmed by MOKE measurements performed across the surface of the film, that showed either the lower or the higher switching field, depending on which area of the film was measured. The 60% Co film does not show hysteresis since it is paramagnetic at room temperature.

Static magnetic properties. (a) In-plane easy axis hysteresis loops, measured by VSM, for single-layer films with 86.5 and 60 at% Co, the continuously modulated composition structure (CMC), and the multilayer (ML). All films have very low coercivity, below 0.5 mT, except for the 60 at% Co film which is paramagnetic. (b) Saturation magnetization as a function Co content in SL Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x thin films. The CMC and the ML are displayed at their mean compositions (subscript mean), and at their effective compositions (subscript eff). The shaded area shows the range of compositions in the CMC and the dotted lines the two compositions in the ML.

The saturation magnetization \(M_s\) for each composition was evaluated by VSM measurements at room temperature. \(M_s\) is found to increase linearly with increasing Co content, as shown in Fig. 2b. This linear increase in \(M_s\) has been observed previously in Ref.14, where it is rationalized by the increasing density of moment-carrying Co atoms and the corresponding reduction of Al and Zr atoms. At room temperature, the films become ferromagnetic above a critical Co concentration of 66.8 at%. Further Co substitution results in an increase in moment, significantly greater than that contributed by each added Co atom (based on the magnetic moment per atom in pure Co). The saturation magnetization was measured at room temperature since the FMR measurements (see below) are performed at that temperature and \(M_s\) is a necessary input parameter for the evaluation of magnetic damping (this is addressed in Ref.26). The influence of temperature on \(M_s\) is naturally greater for the lower Co compositions where the Curie temperature \(T_c\) is not far above room temperature, but this does not seem to alter the observed linear trend. Below 66.8 at% Co, \(T_c\) is below room temperature and therefore films with those compositions have no spontaneous magnetization at the measurement temperature, i.e. they are paramagnetic.

The ML and CMC films are magnetically inhomogeneous systems by design, where the magnetization is modulated along the z direction. The ML film has layers with two distinct compositions, indicated by the vertical dashed lines in Fig. 2b. The lower Co composition has an intrinsic \(T_c\) of 100 K and should therefore be paramagnetic at room temperature, were it not for the magnetic proximity effect9,23. The CMC film has a continuous range of compositions shown by the grey-shaded region. Therefore, the lower Co composition regions of the CMC film should also be intrinsically paramagnetic at room temperature. In order to compare the saturation magnetization of the ML and CMC films to that of SL films we calculate the magnetization by dividing the total measured moment by the total volume of the Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x layers and plot this effective magnetization as a function of the calculated mean composition. The results are shown in Fig. 2 by the solid square and triangle for the ML and CMC film, respectively. The mean compositions are \(\overline{x}_\textrm{ML}=0.731\) and \(\overline{x}_\textrm{CMC}=0.758\). For both the ML and CMC films the saturation magnetization is considerably higher than for the equivalent SL films (with the same mean compositions), or \(M_\textrm{ML} = 520 \pm 10\) kA/m in the ML and \(M_\textrm{CMC} = 566 \pm 8\) kA/m in the CMC film. Another point of view is to determine the effective composition from the measured \(M_s\) values by comparing the ML and CMC to a single-layer with an equivalent saturation magnetization. This is a way of quantifying the magnetic proximity effect in terms of an effective enhancement in the density of the magnetic species. This approach is also shown in Fig. 2 by an open square and triangle. The proximity-induced magnetization is equivalent to an increase in Co content of approximately 3.4 at% and 1.9 at% in the ML and CMC films respectively.

PNR measurements were carried out on the heterostructure films to determine the in-plane magnetization depth profile, and the results are displayed in Fig. 3. The two spin channels (up and down) were fitted simultaneously in Refl1D27, yielding the nuclear and magnetic scattering length density (SLD) as a function of depth z. The confidence intervals were evaluated using the DREAM algorithm, with the epsilon ball initializer. The algorithm also gives information about parameter correlations and this was used to reduce the number of parameters and constraints so as to avoid over-interpreting the data. The intrinsically paramagnetic compositions were allowed to have a non-zero magnetic moment, modeling a possible proximity-induced magnetization.

Magnetic profiles. Polarized neutron reflectivity measurements of the CMC film (a) and the ML (b). Both up and down spin channels are fitted in Refl1D and shown as solid lines. The figure of merit (FOM) for the fits is displayed on the graphs. The nuclear and magnetic SLD were extracted from the fitting of the CMC (c) and the ML (d) films, both 68% and 95% confidence intervals are shown. The secondary y-axes show the magnetic SLD in units of magnetization.

The CMC fitting results (Fig. 3a, c) show a close to sinusoidal magnetic SLD, such that the magnetization varies continuously and smoothly with composition. Fitting with abrupt interfaces and low roughness did not yield good results, as the reflectivity simulation showed additional Bragg peaks at higher angles which are not present in the data. The net magnetization was evaluated by integrating the magnetic SLD, which for the CMC film yields \(M_\textrm{PNR}=563 \pm 8\) kA/m, in excellent agreement with the VSM measurement (\(566 \pm 8\) kA/m). The peaks in magnetization reach 893\(^{+6}_{-4}\) kA/m and the minima are \(74^{+7}_{-4}\) kA/m (where uncertainties represent the 95% confidence interval). The minima of the magnetic SLD are an order of magnitude higher than the magnetization of the corresponding composition, measured on single layer films by VSM. This is consistent with the presence of proximity-induced magnetization and shows that the composition modulated film is completely ferromagnetic with no paramagnetic regions, even though the low-Co regions should be intrinsically paramagnetic. It can also be noted that the first and last peaks in the magnetic SLD are asymmetric as a result of magnetically dead sections that are adjacent to the non-magnetic \(\text {Al}_{0.7}\) \(\text {Zr}_{0.3}\) wetting and capping layers. The ML results are similar but there is a clear additional second-order Bragg peak in the reflectivity (Fig. 3b, d). The nuclear SLD shows abrupt interfaces, as previously seen in the XRR measurements, but the magnetization profile varies smoothly and does not go to zero in the low-Co layers. The fitted nuclear interface width (roughness) is very low, or \(\sigma _n=1.64\) Å, indicating a very smooth interface with negligible Co, Al or Zr diffusion between the layers. In contrast, the magnetic interface is broad, with an estimated interface width of \(\sigma _{\mu }=10\) Å. Again, this shows the magnetic proximity effect which induces a magnetization in the nominally paramagnetic layers. Its extent and size are in good agreement with the results in Refs.9,23, where long-range magnetic proximity effects are reported. The maxima and minima in the magnetization of the multilayer are \(872^{+9}_{-10}\) kA/m and \(81^{+8}_{-9}\) kA/m, respectively. Interestingly, the minima in magnetization are within error the same for the ML and CMC films.

Dynamic magnetic properties

The dynamic magnetic properties were evaluated by FMR measurements. A typical measurement of the real and imaginary part of the magnetic susceptibility is shown in Fig. 4a. To extract the resonance from the background we fit the resonance peak with a composite model of a Lorentzian and a suitable background. In the case displayed in the figure, the background is composed of a step and a linear function. The LLG solution is subsequently fitted to the remaining signal with the background subtracted to evaluate the dynamic parameters, namely the damping \(\alpha\), and the first-order uniaxial anisotropy constant \(K_u\), using the measured \(M_s\) values from VSM. These parameters are displayed as a function of Co content in Fig. 4b. The data points for the ML and CMC films are also included, both using the mean composition approach and the effective composition approach, as described in section “Static magnetic properties”. The vertical dotted lines are the two compositions in the ML and the shaded area shows the range of compositions in the CMC film, as in Fig. 2.

Dynamic magnetic properties. (a) The magnetic susceptibility fitted with a solution to the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert equation including the composite background signal. The background is evaluated by fitting the imaginary part of \(\chi\) with a Lorentzian and a background. The measurement results displayed are for the composition \(x = 0.71\), with \(\alpha =0.0330\pm 0.0004\). (b) Gilbert damping and the first-order uniaxial anisotropy constant as a function of Co content in single-layer Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x thin films. The ML and the CMC are displayed on this mapping at their mean compositions (subscript mean), and at their effective compositions (subscript eff). The dotted lines show the compositions in the ML and the shaded area shows the range of compositions in the CMC film.

The first-order uniaxial anisotropy constant \(K_u\) increases close to linearly with increasing Co content for the SL films, much like the saturation magnetization in Fig. 2b. The origins of anisotropy in amorphous magnets have been a topic of research for decades28,29,30,31,32,33, but the lack of long-range order makes it exceedingly difficult to determine the exact nature of the anisotropic structure giving rise to magnetic anisotropy. In our case, the uniaxial in-plane anisotropy is field-induced during deposition, giving rise to some form of short-range structural order around the magnetic atoms. We can therefore expect the anisotropy to increase with increasing Co density and the resulting increase in magnetic interaction strength. This is precisely what we observe in Fig. 4b. The Gilbert damping coefficient \(\alpha\) follows the opposite trend and is found to increase dramatically as the Co content drops. The damping is greatest at \(x=0.69\) reaching \(\alpha =0.051 \pm 0.001\) but decreases to \(\alpha =0.0098 \pm 0.0001\) for the composition of \(x=0.865\), which is similar to the damping found in permalloy thin films20,26,34.

The FMR spectra of the ML and CMC films each display a single resonance peak, much like the uniform SL films. Additionally, our PNR data from the CMC and ML films shows that they are magnetic throughout, with no paramagnetic regions separating the ferromagnetic regions. Therefore, we treat these heterostructures as uniform ferromagnetic films with a uniform effective magnetization and fit their FMR spectra much like we do for the SL films. The effective magnetization was determined by measurement, as explained above. The anisotropy constants extracted from FMR are found to be significantly higher in the ML and CMC films than in SL films with the same mean compositions, while the damping turns out to be almost the same as in SL films of the same mean composition (filled squares and triangles in Fig. 4b). The ML film has a damping coefficient of \(\alpha _\textrm{ML}=0.0197 \pm 0.0001\) whereas it is \(\alpha _\textrm{CMC}=0.0164 \pm 0.0001\) in the CMC film. Again, it is instructive to consider the effective composition picture where the anisotropy and damping are plotted based on the composition of SL films with equal magnetization as illustrated in Fig. 2 (displayed as open squares and triangles in Fig. 4b). In this representation, we see that the anisotropy is fairly consistent with that of SL films with the same magnetization. The damping in the CMC film is also consistent with the damping in SL films with the same magnetization but the ML film has somewhat higher damping. We can therefore conclude that the damping and anisotropy are similarly affected by the proximity effect as the magnetization, although there may be additional factors contributing to the slightly enhanced damping in the ML structure.

Discussion

Magnetic damping is normally caused by multiple effects which are viewed as additive terms, and are categorized as intrinsic and extrinsic. The two features that are probed in this study are the intrinsic effect of thermal fluctuations and the extrinsic effect of magnetic and structural inhomogeneity. These effects can be assessed in our structures since, on the one hand, \(T_c\) decreases to below room temperature with decreasing Co content while the FMR measurement temperature is fixed. Decreasing Co concentration therefore corresponds to bringing \(T_c\) closer to the measurement temperature. On the other hand, by design, the CMC and ML films have a high structural inhomogeneity on the same length scale as we anticipate composition variations in films of nominally fixed composition14,19. FMR measurements performed at temperatures near the Curie temperature of ferromagnetic thin films activate pathways to non-uniform precessional modes that dissipate energy from the uniform precessional mode. This results in a broadening of the FMR peak and a greater damping of the magnetization35,36, much like we observe in Fig. 4b. The increase in damping near \(T_c\) has been a theoretical topic of research for decades37,38,39. The \(T_c\) of CoAlZr depends linearly on composition, with a large positive slope14, and therefore \(T_c\) approaches our measurement temperature with decreasing Co content, eventually dropping below it. The composition of \(x=0.667\) Co has \(T_c = 288\) K and is thus paramagnetic at room temperature with no FMR response. Compositions slightly above are ferromagnetic, such as \(x=0.686\) which has a \(T_c= 376\) K. The measured increase in damping with decreasing Co content, seen in Fig. 4, is thus in agreement with an intrinsic temperature-dependent mechanism.

The onset of increased damping can be gauged using a “reduced temperature” \(T/T_c\), which is the ratio of the measurement temperature \(T= 296\) K and the Curie temperature \(T_c\)36. The damping starts to increase steeply in our films below approximately \(x=0.73\) which corresponds to a reduced temperature of \(T/T_c = 0.51\). This reduced temperature is lower than that seen in the ferromagnetic elements. For example, in Ref.36 it is shown that damping increases at temperatures above \(T/T_c=0.8\) for Ni, Co, Fe, and Gd on Cu or W substrates, in a thickness range below and up to 20 monolayers. Our results therefore show that temperature starts to contribute to the damping further from \(T_c\) in our amorphous films. The extrinsic contribution of magnetic inhomogeneities to the damping could provide an explanation for the low onset temperature compared to other systems. Spatial variations in the local Curie temperature would result in regions of the film being closer to the local \(T_c\), thus contributing to a rise in damping at higher Co compositions than expected if the composition was uniform.

The ML and the CMC heterostructures were synthesized to study how forced inhomogeneity, at the same length scale as the inherent spatial variation in composition, and proximity effects influence magnetic damping. The ML has compositions \(x=0.85\) and \(x=0.60\) while the CMC composition varies sinusoidally between the same extreme compositions. In the ML, 47% of the thin film (all layers with \(x_\textrm{min}\)) should, based their composition, be intrinsically paramagnetic while the remaining 53% have an \(\alpha\) of around 0.01. Ignoring the presence of the paramagnetic layers, one might therefore expect independently precessing ferromagnetic layers with \(\alpha =0.01\). However, the measured damping is almost double that value, or 0.0197. Interestingly, this is greater than the \(\alpha _\textrm{CMC}=0.0164\) for the CMC film, where 32% of the volume should be intrinsically paramagnetic. Also, based on the single layer results, the damping in the nominally ferromagnetic portion of the CMC film should range from 0.01 to 0.05. Nevertheless, the overall result is that \(\alpha _\textrm{CMC}\) is lower than \(\alpha _\textrm{ML}\).

The detailed analysis of spin-pumping and the proximity effect in this material is a topic of further study12,40. However, our FMR measurements, both along the easy axis and angle-dependent measurements, support the conclusion that the heterostructures act as uniformly magnetized ferromagnetic films with a proximity-induced effective magnetization that is somewhat higher than that calculated from the mean composition, as shown in Fig. 2b. We can conclude that proximity effects on damping are present and that magnetic inhomogeneity does not contribute to damping in these systems as strongly as might be expected. The enhanced damping is greatest in the ML film with ferromagnetic layers of the lowest damping separated with abrupt interfaces by layers of composition with significantly higher damping. This may be related to spin pumping which is known to enhance damping in ML systems, even in the presence of proximity effects41,42,43.

Conclusions

We have examined the static and dynamic magnetic properties of CoAlZr amorphous magnets with a modulated composition depth profile and compared them to films of uniform composition. Saturation magnetization increases close to linearly with Co content as previously reported. Static measurements show that both a conventional multilayer and a continuously modulated composition result in a magnetization that is higher than that of a uniform film with the same mean Co content, despite having a large proportion of nominally paramagnetic layers/regions. This is due to a large magnetic proximity effect which induces a magnetization in nominally non-magnetic layers or regions, equivalent to that of an increase in mean Co content of approximately 3.4 and 1.9 at%, in the multilayer and continuously modulated composition sample, respectively. The enhancement of the saturation magnetization is similar in the multilayer and the continuously modulated film, showing that the proximity effect is equally effective across abrupt interfaces as it is across smooth composition gradients. PNR measurements of both heterostructures show the presence of proximity-induced magnetization. The magnetization profile of the continuously modulated composition film is shown to change sinusoidally with depth and both heterostructures have non-zero magnetization in the nominally paramagnetic layers.

FMR measurements show that the first-order uniaxial anisotropy constant increases linearly with Co content in single-layer CoAlZr amorphous thin films. The damping coefficient \(\alpha\) is very low in high-Co content films but increases dramatically with decreasing Co content in the range where CoAlZr single-layers remain ferromagnetic. The increase is attributed to the change in Curie temperature with composition as the damping increases substantially in ferromagnetic systems in proximity to \(T_c\). The Gilbert damping is found to be slightly higher in the multilayer than in the continuously modulated composition film, while both are found to be comparable to single-layer CoAlZr with the same mean composition. The extremely low damping in both heterostructures establishes the importance of proximity effects for magnetization dynamics. Proximity-induced magnetic regions have a significantly reduced Gilbert damping contribution compared to the intrinsic damping expected for such low-Co containing compositions. Therefore, it is clear that magnetic proximity effects play an important role for both the static and dynamic magnetic properties of amorphous thin films.

Methods

The CoAlZr films were deposited in a DC magnetron sputtering system with a base pressure of \(1 \times 10^{-9}\) mbar. The substrates were polished Si(001) with a 2 nm thick native oxide, which were annealed in vacuum at \(200~^\circ {\hbox {C}}\) for 30 min prior to deposition. The deposition was performed at ambient temperature at an Ar (99.999%) pressure of \(2.85 \times 10^{-3}\) mbar. A range of Cox(Al0.7Zr0.3)1−x single layer films with \(0.60\le x<0.87\) were deposited by co-sputtering from 3-inch diameter circular Co and \(\text {Al}_{0.7}\)\(\text {Zr}_{0.3}\) targets, both of 99.9% purity. The composition was controlled by varying the power applied to the Co magnetron in the range 57–214 W while keeping the power of the AlZr magnetron fixed at 50 W. The Co power was computer-controlled and was either kept constant to obtain a fixed composition or it was actively varied during growth to produce films with a modulated composition. To eliminate any substrate influence on the short-to-medium range order in the amorphous CoAlZr, a 10 nm thick AlZr wetting layer was used14. All films were then capped with 5 nm of AlZr to prevent oxidation of the magnetic layers beneath. The films were deposited in a uniform in-plane magnetic field of 130 mT, provided by eight SmCo magnets and a yoke fixed to the sample holder. This induces a uniaxial in-plane anisotropy parallel with the field14. Furthermore, the films were deposited through a circular shadow mask, 4.0 mm in diameter. This was done to reduce in-plane shape effects when rotating the moment in the plane during magnetic measurements.

X-ray reflectivity (XRR) and grazing incidence X-ray diffraction (GIXRD) measurements were performed to determine the layer thicknesses, density, crystallinity, and both interface and surface roughness. All films were found to be x-ray amorphous, in line with previous results of Thórarinsdóttir et al.14. The composition was determined by careful calibration of the deposition rates from each target, which was evaluated with XRR measurements of Co and AlZr films. This approach is known to be reliable for producing amorphous alloys of a given composition in cases where the sticking coefficient is close to unity for all the alloy elements44,45. Further information regarding the x-ray system and the optics used can be found in Ref.45.

Magneto-optic Kerr effect (MOKE) magnetometry and vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) were used to study the static magnetic properties. These properties include magnetic anisotropy, coercivity, remanence and saturation magnetization. Polarized neutron reflectivity (PNR) measurements were performed at the POLREF beamline at the ISIS Neutron and Muon source in the UK46. The measurements were performed at room temperature with an in-plane applied field of 700 mT. The measurements are ideal for determining the depth profile of the magnetization throughout a thin film, allowing quantification of magnetic dead layers and proximity-induced magnetization.

Dynamic magnetic properties, including the resonance frequency, magnetic damping (Gilbert damping coefficient \(\alpha\)), and anisotropy, were investigated by ferromagnetic resonance (FMR) measurements using a broadband (a network analyzer) strip-loop technique described in26,47. This includes fitting the FMR susceptibility data with a solution to the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert (LLG) equation21,26

Here \(\gamma\) is the gyromagnetic ratio, \(\bf{H}_{\tt eff}\) is the effective internal magnetic field, \(\alpha\) is the Gilbert damping coefficient and \(\bf M\) is the magnetization.

Data availibility

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. This work includes measurements performed at STFC ISIS Neutron and Muon Source. The datasets are available at (https://doi.org/10.5286/ISIS.E.RB2390114-1).

References

Moser, A. et al. Magnetic recording: Advancing into the future. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 35, R157–R167. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/35/19/201 (2002).

Hirohata, A. et al. Review on spintronics: Principles and device applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 509, 166711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2020.166711 (2020).

Chumak, A. V., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnonic crystals for data processing. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50, 244001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aa6a65 (2017).

Sun, J. Z. et al. Spin-torque switching efficiency in CoFeB-MgO based tunnel junctions. Phys. Rev. B 88, 104426. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.88.104426 (2013).

Mihai Miron, I. et al. Fast current-induced domain-wall motion controlled by the Rashba effect. Nat. Mater. 10, 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1038/NMAT3020 (2011).

Parkin, S. S. P., Hayashi, M. & Thomas, L. Magnetic domain-wall racetrack memory. Science 320, 190–194. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1145799 (2008).

Schrag, B. D. et al. Néel “orange-peel’’ coupling in magnetic tunneling junction devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 77, 2373–2375. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1315633 (2000).

Parkin, S. S. P., More, N. & Roche, K. P. Oscillations in exchange coupling and magnetoresistance in metallic superlattice structures: Co/Ru, Co/Cr, and Fe/Cr. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2304–2307. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.64.2304 (1990).

Magnus, F. et al. Long-range magnetic interactions and proximity effects in an amorphous exchange-spring magnet. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11931 (2016).

Greer, A. L. Metallic glasses. Science 267, 1947–1953. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.267.5206.1947 (1995).

Kittel, C. Quantum Theory of Solids 2nd edn. (Wiley, New York, 1987).

Swindells, C. & Atkinson, D. Interface enhanced precessional damping in spintronic multilayers: A perspective. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 170902. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0080267 (2022).

Shao, Q. et al. Roadmap of spin-orbit torques. IEEE Trans. Magn. 57, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2021.3078583 (2021).

Thórarinsdóttir, K. A. et al. Finding order in disorder: Magnetic coupling distributions and competing anisotropies in an amorphous metal alloy. APL Mater. 10, 041103. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0078748 (2022).

Fallarino, L., Kirby, B. J. & Fullerton, E. E. Graded magnetic materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 54, 303002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/abfad3 (2021).

Kirby, B. et al. Spatial evolution of the ferromagnetic phase transition in an exchange graded film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 047203. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.047203 (2016).

Barsukov, I. et al. Frequency dependence of spin relaxation in periodic systems. Phys. Rev. B 84, 140410. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.140410 (2011).

Zheng, Z. et al. Field-free spin-orbit torque-induced switching of perpendicular magnetization in a ferrimagnetic layer with a vertical composition gradient. Nat. Commun. 12, 4555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24854-7 (2021).

Gemma, R., Baben, M. t., Pundt, A., Kapaklis, V. & Hjörvarsson, B. The impact of nanoscale compositional variation on the properties of amorphous alloys. Scientific Reports10, 11410, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67495-4 (2020).

Ingvarsson, S., Xiao, G., Parkin, S. S. P. & Koch, R. H. Tunable magnetization damping in transition metal ternary alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 4995–4997 (2004).

Ingvarsson, S. et al. Role of electron scattering in the magnetization relaxation of thin \(\text{Ni}_{81}\) films. Phys. Rev. B 66, 214416. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.66.214416 (2002).

Ingvarsson, S., Trouilloud, P. L., Sun, S., Koch, R. H. & Abraham, D. W. Magnetic materials having superparamagnetic particles. US Patent no. 8324009, February 2011. International Business Machines Corporation (IBM).

Thórarinsdóttir, K. A., Palonen, H., Palsson, G. K., Hjörvarsson, B. & Magnus, F. Giant magnetic proximity effect in amorphous layered magnets. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 054409. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevmaterials.3.054409 (2019).

Magnus, F. et al. Tuneable exchange-spring stiffness in amorphous magnetic trilayer structures. J. Phys. Condens. Matter https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648x/ac1c2c (2021).

Björck, M. & Andersson, G. GenX: An extensible X-ray reflectivity refinement program utilizing differential evolution. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 1174–1178. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889807045086 (2007).

Tryggvason, A. Ferromagnetic resonance study of permalloy and CoAlZr thin films. Master’s thesis, University of Iceland (2022).

Kienzle, P. A., Maranville, B. B., O’Donovan, K. V., Ankner, J. F., Berk, N. F. & Majkrzak, C. F. https://www.nist.gov/ncnr/reflectometry-software (2017).

Yan, X., Hirscher, M., Egami, T. & Marinero, E. E. Direct observation of anelastic bond-orientational anisotropy in amorphous \({\text{ Tb }}_{26}\)\({\text{ Fe }}_{62}\)\({\text{ Co }}_{12}\) thin films by X-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 43, 9300–9303. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.43.9300 (1991).

Harris, V., Aylesworth, K., Das, B., Elam, W. & Koon, N. Structural origins of magnetic-anisotropy in sputtered amorphous Tb-Fe films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 1939–1942. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.1939 (1992).

Hellman, F. & Gyorgy, E. M. Growth-induced magnetic anisotropy in amorphous Tb-Fe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 68, 1391–1394. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.1391 (1992).

Harris, V. G., Hellman, F., Elam, W. T. & Koon, N. C. Substrate temperature effect on the structural anisotropy in amorphous Tb-Fe films. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 5785–5787. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.353572 (1993).

Hellman, F. Surface-induced ordering: A model for vapor-deposition growth of amorphous materials. Appl. Phys. Lett. 64, 1947–1949. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.111751 (1994).

Magnus, F. et al. Tunable giant magnetic anisotropy in amorphous SmCo thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 162402. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4802908 (2013).

Cao, W., Yang, L., Auffret, S. & Bailey, W. E. Nearly isotropic spin-pumping related gilbert damping in Pt/Ni81Fe19/Pt. Phys. Rev. B 99, 094406. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.99.094406 (2019).

Sparks, M. Ferromagnetic-Relaxation Theory (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964).

Platow, W., Anisimov, A. N., Dunifer, G. L., Farle, M. & Baberschke, K. Correlations between ferromagnetic-resonance linewidths and sample quality in the study of metallic ultrathin films. Phys. Rev. B 58, 5611–5621. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.58.5611 (1998).

Lyberatos, A., Berkov, D. V. & Chantrell, R. W. A method for the numerical simulation of the thermal magnetization fluctuations in micromagnetics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 5, 8911–8920. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/5/47/016 (1993).

Lyberatos, A. & Guslienko, K. Thermal stability of the magnetization following thermomagnetic writing in perpendicular media. J. Appl. Phys. 94, 1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1585118 (2003).

Chubykalo-Fesenko, O., Nowak, U., Chantrell, R. W. & Garanin, D. Dynamic approach for micromagnetics close to the Curie temperature. Phys. Rev. B 74, 094436. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.74.094436 (2006).

Montoya, E. et al. Spin transport in tantalum studied using magnetic single and double layers. Phys. Rev. B 94, 054416. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.94.054416 (2016).

Bansal, R., Chowdhury, N. & Muduli, P. K. Proximity effect induced enhanced spin pumping in Py/Gd at room temperature. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 262403. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5033418 (2018).

Khodadadi, B. et al. Enhanced spin pumping near a magnetic ordering transition. Phys. Rev. B 96, 054436. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.054436 (2017).

Omelchenko, P., Girt, E. & Heinrich, B. Test of spin pumping into proximity-polarized Pt by in-phase and out-of-phase pumping in Py/Pt/Py. Phys. Rev. B 100, 144418. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.100.144418 (2019).

Frisk, A., Magnus, F., George, S., Arnalds, U. B. & Andersson, G. Tailoring anisotropy and domain structure in amorphous TbCo thin films through combinatorial methods. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 49, 035005. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/49/3/035005 (2015).

Tryggvason, T. et al. Corrosion resistance of W and Ta based amorphous coatings in a geothermal steam environment—A combinatorial study. Geothermics 88, 101859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geothermics.2020.101859 (2020).

See https://www.isis.stfc.ac.uk/Pages/polref.aspx for Polref Beamline (2020), accessed on April 16, 2024.

Korenivski, V. et al. A method to measure the complex permeability of thin films at ultra-high frequencies. IEEE Trans. Magn. 32, 4905–4907. https://doi.org/10.1109/20.539283 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Icelandic Research Fund (grants no. 228951 and 218029), and the University of Iceland Research Fund (grants no. 94157 and 92332).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. conceived, conducted, and analyzed the experiment(s), S.I. and F.M. conceived and supervised the experiment(s), A.C. and C.K. conducted the PNR measurements and supervised analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the Supplementary file, which was included with the initial submission, was omitted. The correct Supplementary Information file now accompanies the original Article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tryggvason, A., Caruana, A., Kinane, C. et al. Magnetization dynamics and proximity effects in ultrasoft composition modulated amorphous CoAlZr alloy thin films. Sci Rep 15, 7388 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91332-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91332-1