Abstract

Recent studies have shown that the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) can predict short-term and long-term outcomes in acute ischemic stroke (AIS) patients. However, the relationship of the variation of NLR (ΔNLR) with hemorrhage transformation (HT) and early neurological improvement (ENI) after intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the impact of ΔNLR on HT and ENI at 24 h post-IVT and its association with different TOAST classifications. AIS patients undergoing IVT between October 2021 and October 2023 were enrolled and classified by TOAST criteria. Patients were grouped based on the presence or absence of HT and ENI. Our study demonstrated that both HT and ENI were associated with ΔNLR, which was an independent influencing factor for HT and ENI following IVT. Specifically, the ΔNLR in the small artery occlusion (SAO) group was higher than that in the minor stroke of large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) subtype. Thus, ΔNLR may serve as a useful biomarker to assist in diagnosis and monitor the outcomes of thrombolytic therapy in AIS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a condition that results in persistent disability and contributes to high mortality globally1. Multiple randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) within 4.5 h of stroke onset significantly improves the likelihood of a favorable prognosis, regardless of age or stroke severity2. However, hemorrhagic transformation (HT) is a serious complication of acute ischemic stroke (AIS), typically occurring within 24 h after thrombolysis. The complication can exacerbate the disease and significantly increase the disability and mortality rates at 3 months3,4. Therefore, predicting and analyzing HT is of great importance.

Neutrophils, early responders in the blood following AIS, contribute to ischemic brain injury, thrombosis, and atherosclerosis, while lymphocytes may protect against ischemic injury by suppressing inflammation5,6. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) not only reflects the counts of neutrophils and lymphocytes but also indicates the over-activation of neutrophils, resulting in a larger disparity between these two subtypes of white blood cells7. The ratio offers advantages over studying only the two subtypes of leukocytes individually7. Previous studies have identified baseline NLR as an independent predictor of early neurological improvement (ENI), HT, and mortality in AIS patients8,9,10. Given that the counts of neutrophils and lymphocytes change dynamically in stroke11,12, the variation in NLR (ΔNLR) can reflect the progression of AIS patients after thrombolysis. However, the relationship between ΔNLR and post-thrombolysis early neurological outcomes has not been extensively studied.

We examined the relationship between ΔNLR and HT, as well as ENI following IVT in AIS patients. Additionally, given the scarcity of studies on the relationship between ΔNLR and TOAST classification, our study was the first to investigate the association between ΔNLR and various TOAST classifications.

Participants and methods

Study population

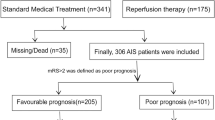

AIS patients undergoing intravenous thrombolysis within 4.5 h were recruited from the Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. All the patients were treated in the stroke units and received standard treatments, for instance, antiplatelet therapy and statin therapy. Informed consent was obtained from participants or their legal representatives. The study inclusion criteria were: (1) Admission within 4.5 h after onset; (2) Treated with intravenous thrombolysis; (3) Eighteen years or older. The study exclusion criteria were: (1) Autoimmunity disease, malignant tumor or severe hepatic and renal insufficiency; (2) Incomplete clinical data (Fig. 1). Stroke subtype was classified according to Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) criteria13.

Data collection

Basic clinical data of all subjects, including gender, age, baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, onset to treatment time (OTT), admission systolic blood pressure, admission diastolic blood pressure, Body Mass Index (BMI) and vascular risk factors [hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease (CHD), atrial fibrillation, current smoking and current drinking] were obtained by two professional neurologists and two trained nurses. All patients underwent electrocardiogram, brain CT, brain MRI which included the sequences of T1, T2, Flair (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery), DWI (diffusion-weighted imaging), ADC (apparent diffusion coefficient)] and MRA (magnetic resonance angiography), chest CT, whole brain and cervical CT angiography (CTA) and digital subtraction angiography if it was necessary to determine the etiological classification. Patients fasted for at least 8 h before fasting blood collection. Routine biochemistry which included aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin (TBIL), blood glucose (Glu), urea, creatinine, and C-reactive protein (CRP) and complete blood count analysis were obtained from the biochemistry Laboratory of Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. We calculated ΔNLR as follows: baseline NLR minus NLR after IVT. The complete blood count analysis, brain CT and the NIHSS score was performed again at 24 h following IVT. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was performed at 7 days following IVT. We calculated the variation of NIHSS score (ΔNIHSS score) as follows: baseline NIHSS score minus NIHSS score after IVT. Post-thrombolysis ENI was defined as a decrease in the NIHSS score by ≥ 4 points in the total score or a complete resolution of neurological deficits within 24 h after thrombolysis9,14.

Statistical analysis

For continuous variables, summary statistics were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (\(\bar{X}\) ± SD) or median (interquartile range) (M [Q1, Q3]) depending on the distribution of statistical data. The categorical variables were expressed as n (%). Independent t-test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution, and Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normal distribution. Comparisons between categorical variables were made using Pearson χ2 test or Fisher′s exact test. Spearman correlation analysis was performed to determine associations between variables. Univariable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were used to determine the independent risk factors of HT and ENI by obtaining odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were applied to evaluate the ability of ΔNLR in identifying HT and ENI. SPSS 23.0 software was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Among the 234 patients, 39 developed HT. According to the presence or absence of HT, the main baseline characteristics of patients were shown in Table 1; Fig. 2. Compared with the non-HT group, the HT group had higher levels of age, NIHSS score before IVT, baseline NLR and the proportion of patients with a history of atrial fibrillation (P < 0.05). In contrast, the levels of OTT and platelets were lower in those HT patients. The ΔNLR in HT group (-2.86[-5.95, -0.19]) was lower than that in non-HT group (0.02[-0.62, 0.79]) (P < 0.001). Other clinical parameters in the two groups were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Of 195 patients who did not develop HT, 89 presented ENI. Based on the presence or absence of ENI, the main baseline characteristics of patients were shown in Table 2; Fig. 3. Thus, the ENI group had lower systolic blood pressure, larger baseline neutrophils, and larger baseline NLR compared with the non-ENI group (P < 0.05). The ΔNLR in ENI group (0.40[-0.05, 1.75]) was higher than that in non-ENI group (-0.58[-1.16, 0.29]) (P < 0.001). Other clinical parameters were not statistically significant between them (P > 0.05).

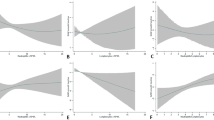

Study on the correlation between NLR variation and HT

There were statistically significant differences in age, ΔNLR, pre-thrombolytic NIHSS score, OTT, platelet, baseline NLR, and history of atrial fibrillation between the HT group and the non-HT group. Binary Logistic regression analysis was performed for the above indicators. We found that ΔNLR was an independent predictor of HT after adjusting for age, pre-thrombolytic NIHSS score, OTT, platelets, baseline NLR, and history of atrial fibrillation (Table 3). Patients with higher ΔNLR had a 0.580-fold(95% CI 0.467–0.720, P <0.001, Table 3) higher risk of developing HT. ΔNLR was included in ROC curve analysis (Fig. 4). The area under the curve (AUC) of ΔNLR differentiating HT was 0.749 [95%CI (0.644–0.854), p < 0.001)], with a sensitivity of 61.5% and specificity of 92.8%, indicating that ΔNLR had good predictive value (AUC > 0.7), and the cut-off value was − 2.26.

Correlation study between NLR variation and ENI

There were statistically significant differences in ΔNLR, systolic blood pressure, baseline neutrophils and baseline NLR between ENI group and non-ENI group. Binary Logistic regression analysis was performed for the above indicators. We found that ΔNLR was an independent predictor of ENI (Table 4). Patients with higher ΔNLR had a 2.369-fold(95% CI 1.629–3.444, P < 0.001, Table 4) higher risk of developing ENI. ΔNLR was included in ROC curve analysis (Fig. 5). ΔNLR distinguished ENI with an AUC of 0.768 [95%CI (0.72–0.835), P < 0.001)], suggesting that ΔNLR had good predictive value (AUC > 0.7). The cut-off value was − 0.49 with a sensitivity of 93.3% and specificity of 60.4%.

In order to further explore the relationship between ΔNLR and ΔNIHSS score, we conducted Spearman correlation analysis to assess the relationship between ΔNLR and ΔNIHSS score in AIS patients. It could be seen that ΔNLR was positively correlated with ΔNIHSS score of AIS patients (r = 0.289, p <0.001). And Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between ΔNLR and 7-day mRS score in AIS patients. It could be seen that ΔNLR was negatively correlated with mRs score of AIS patients (r=-0.345, p <0.001).

Association of ΔNLR with early outcomes after IVT in patients with different TOAST classification

Association of ΔNLR with early outcomes after IVT in atherosclerotic and cardioembolic patients

Among the 234 patients, 198 were atherosclerosis (AS) subtype and 36 were cardiac embolism (CE) subtype. The main baseline characteristics of the patients were shown in Table 5; Fig. 6. The incidence of HT in CE group (41.67%) was higher than that in AS group (12.12%) (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the incidence of ENI between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared with AS group, CE group had older age, higher pre-thrombolytic NIHSS score, lower systolic blood pressure, fewer platelets, higher urea, higher CRP, and a greater proportion of patients with a history of atrial fibrillation (P < 0.05). The ΔNLR in CE group (-0.31[-2.94, 0.50]) was lower than that in AS group (-0.04[-0.75,0.75]) (P < 0.05). Binary Logistic regression analysis was carried out for the above indicators. We found that ΔNLR was not an independent factor between AS group and CE group (OR 0.987, 95% CI 0.822–1.185, P = 0.886, Table 6).

Association of ΔNLR with early outcomes after IVT in patients with minor stroke of large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) subtype and small artery occlusion

Among the 234 patients, there were 30 patients with minor stroke of LAA subtype (NIHSS score ≤ 3)15 and 118 patients with small artery occlusion (SAO) subtype. The main baseline characteristics of the patients were shown in Table 7; Fig. 7. The incidence of HT in the minor stroke of LAA group (20.00%) was higher than that in the SAO group (5.08%), and the incidence of ENI in the SAO group (39.83%) was higher than that in the minor stroke of LAA group (20.00%) (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in NIHSS score before IVT between the two groups (P > 0.05). Compared with the minor stroke of LAA group, the SAO group had a younger age and a larger ALT (P < 0.05). The ΔNLR in SAO group (0.25[-0.30, 1.09]) was higher than that in minor stroke of LAA group (-0.55[-1.20,0.11]) (< 0.001). Binary Logistic regression analysis was performed on the relevant indicators. We found that, after adjusting for other factors, ΔNLR was an independent factor between the minor stroke of LAA group and the SAO group (OR 1.542, 95% CI 1.158–2.052, P = 0.003, Table 8). ΔNLR was included in ROC curve analysis (Fig. 8). The AUC of ΔNLR differentiating the minor stroke of LAA group from the SAO group was 0.716 [95%CI (0.613–0.819), P < 0.001)], the cut-off value was − 0.20, the sensitivity was 71.2%, and the specificity was 66.7%.

Discussion

This study was the first time to confirm the correlation of ΔNLR with HT and ENI 24 h after IVT in AIS patients. The ΔNLR was calculated as follows: baseline NLR minus NLR after IVT. Therefore, if the variation of NLR was a positive value, it means that the NLR after thrombolysis was lower than the baseline; if the variation was a negative value, it means that the NLR after thrombolysis was higher than the baseline. In this study, it was found that NLR increased more significantly after IVT in patients with HT, and NLR decreased more significantly after IVT in patients with ENI. After adjusting for other factors, ΔNLR was an independent influence factor on HT and ENI after IVT. Moreover, ΔNLR was positively correlated with ΔNIHSS score of AIS patients (r = 0.289, p <0.001), and it was negatively correlated with Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 7 days following IVT (r=-0.345, p <0.001). And the NLR decreased more significantly after IVT in patients with SAO subtype than that in minor stroke of LAA subtype. However, there was no significant difference in ΔNLR between patients of AS subtype and CE subtype.

The influence of neutrophils on HT and prognosis in AIS patients may be attributed to their roles in ischemic injury and disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). As one of the earliest responding cells following AIS5, neutrophils can act on tight-junction proteins via matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) to open the BBB, or they can be internalized into endothelial cells and affect the basement membrane3. Both mechanisms contribute to the increased incidence of HT following thrombolysis in AIS patients16. Previous study have proposed that in LAA subtype stroke, plasma neutrophil elastase (NE) may also be an important mediator of high neutrophil involvement in HT17. Additionally, other factors released by neutrophils after AIS, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) (e.g., superoxide, hypochlorous acid), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and various chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CCL3, CCL5), can not only affect the BBB and brain parenchyma18, but also impair the fibrinolytic system by stimulating the production of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1)19, thereby influencing patient prognosis.

Lymphocytes contribute positively to the prognosis of AIS patients following IVT. The lymphocyte count serves as a general health indicator, reflecting the effects of acute physiological stress20. It can indicate the stress response mediated by cortisol and the level of sympathetic activation21. An increase in lymphocyte count can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby mitigating ischemic injury and enhancing the incidence of ENI22. Studies have demonstrated that regulatory T cells (Tregs) and regulatory B cells (Bregs) exhibit protective effects in certain inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system23,24,25. This suggests that lymphocytes may protect against ischemic brain injury by suppressing inflammation, thereby improving the prognosis of AIS patients after IVT6. However, the specific mechanisms and the roles of various lymphocyte subtypes in HT and ENI following IVT in AIS patients remain to be further elucidated. This study focused on the variation of NLR, which comprehensively reflected the inflammatory role of neutrophils and the immune role of lymphocytes26. Neutrophil-mediated release of inflammatory cytokines may induce lymphocyte apoptosis7. Due to overactivation of neutrophils, the gap between neutrophils and lymphocytes could increase, resulting in significant changes in NLR.

TOAST classification is widely used internationally for AIS. Patients with CE stroke exhibit a higher incidence of HT compared to other subtypes, resulting in more severe brain injury and higher disability and mortality rates. This is associated with a high-inflammatory environment caused by complex mechanisms at the genetic, molecular, and cellular levels27. In this study, we observed that the CE group had a higher incidence of HT than the AS group, although ΔNLR was not identified as an independent influencing factor between these two groups. Compared with SAO stroke, patients with LAA cerebral infarction have higher NIHSS score at admission, more severe neurological impairment and worse clinical prognosis28. They were also more likely to develop HT. Feng, X29. et al. found that higher levels of neutrophil counts and NLR were associated with higher stress hyperglycemia ratio levels in AIS patients with LAA. They speculated that stress hyperglycemia may contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis by affected peripheral blood lymphocytes and neutrophils and disrupting BBB in patients with LAA29. In this study, we compared patients with minor LAA subtype stroke to those with SAO stroke. After balancing the pre-thrombolysis NIHSS scores across groups, we still observed that patients with minor LAA stroke had a higher incidence of HT, a lower incidence of ENI, and a lower ΔNLR. Patients in the minor LAA stroke group exhibited significantly higher NLR and more severe inflammatory responses after intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) compared to baseline. This difference between subtypes was independent of the baseline NIHSS score.

The main advantage of the study was that the blood samples of all patients were collected twice, which could reflect the changes of NLR, so as to observe the relationship of the dynamic changes of leukocyte with cerebral hemorrhage complications of thrombolytic therapy and the improvement of NIHSS score. We further examined the differences in ΔNLR before and after intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) among AIS patients with different subtypes using the TOAST classification. Additionally, this study employed strict exclusion criteria. Previous research has shown that infection is associated with increased white blood cell counts and early adverse neurological outcomes in AIS patients30 To minimize potential confounders, we excluded patients with infections. Nonetheless, our study has several limitations. First, it was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size. Therefore, multicenter studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate our findings. Second, we did not investigate the relationship between long-term prognosis and ΔNLR in patients with different TOAST classifications after IVT. Thus, the association between ΔNLR and long-term outcomes following IVT in AIS patients with different TOAST classifications needs further investigation.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that both HT and ENI were associated with ΔNLR, which was an independent influencing factor for HT and ENI following IVT. Specifically, the ΔNLR in the SAO group was higher than that in the minor LAA group. Therefore, ΔNLR, in conjunction with baseline NLR, can be used to assess the risk of HT. Moreover, ΔNLR may serve as a feasible strategy to monitor and predict the outcomes of thrombolytic therapy in AIS patients.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Global regional, and National burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 20 (10), 795–820 (2021).

Emberson, J. et al. Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with Alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet 384 (9958), 1929–1935 (2014).

Jickling, G. C. et al. Hemorrhagic transformation after ischemic stroke in animals and humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 34 (2), 185–199 (2014).

Shimada, Y. et al. Phosphorylated Recombinant HSP27 protects the brain and attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption following stroke in mice receiving intravenous tissue-plasminogen activator. PLoS One. 13 (5), e0198039 (2018).

Jickling, G. C. et al. Targeting neutrophils in ischemic stroke: Translational insights from experimental studies. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 35 (6), 888–901 (2015).

Guo, Z. et al. Dynamic change of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolysis in stroke. J. Neuroinflam.. 13 (1), 199 (2016).

Shantsila, E. & Lip, G. Y. Stroke in atrial fibrillation and improving the identification of ‘high-risk’ patients: The crossroads of immunity and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 13 (11), 1968–1970 (2015).

Maestrini, I. et al. Higher neutrophil counts before thrombolysis for cerebral ischemia predict worse outcomes. Neurology 85 (16), 1408–1416 (2015).

Tian, C. et al. Association of lower leukocyte count before thrombolysis with early neurological improvement in acute ischemic stroke patients. J. Clin. Neurosci. 56, 44–49 (2018).

Gong, P. et al. The association of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to lymphocyte ratio, and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio with post-thrombolysis early neurological outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J. Neuroinflammation. 18 (1), 51 (2021).

Juli, C. et al. The lymphocyte depletion in patients with acute ischemic stroke associated with poor neurologic outcome. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 1843–1851 (2021).

Sharma, D., Spring, K. J. & Bhaskar, S. M. M. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in acute ischemic stroke: Immunopathology, management, and prognosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 144 (5), 486–499 (2021).

Adams, H. P. Jr. et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 24 (1), 35–41 (1993).

Lin, C. M. et al. Computed tomography angiography in acute stroke patients receiving Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: Outcome and safety evaluations in an Asian population. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 49 (1), 62–69 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl. J. Med. 369 (1), 11–19 (2013).

Gautier, S. et al. Neutrophils contribute to intracerebral haemorrhages after treatment with Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator following cerebral ischaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 156 (4), 673–679 (2009).

Li, L. et al. Association of admission neutrophil Serine proteinases levels with the outcomes of acute ischemic stroke: A prospective cohort study. J. Neuroinflam.. 20 (1), 70 (2023).

Segel, G. B., Halterman, M. W. & Lichtman, M. A. The paradox of the neutrophil’s role in tissue injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 89 (3), 359–372 (2011).

Huang, M., Cai, S. & Su, J. The pathogenesis of Sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(21), e418 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Association between neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 187, 361–362 (2015).

Acanfora, D. et al. Relative lymphocyte count: A prognostic indicator of mortality in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Am. Heart J. 142 (1), 167–173 (2001).

Park, B. J. et al. Relationship of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio with arterial stiffness and coronary calcium score. Clin. Chim. Acta. 412 (11–12), 925–929 (2011).

Shichita, T. et al. Pivotal role of cerebral interleukin-17-producing gammadeltat cells in the delayed phase of ischemic brain injury. Nat. Med. 15 (8), 946–950 (2009).

Gelderblom, M. et al. Neutralization of the IL-17 axis diminishes neutrophil invasion and protects from ischemic stroke. Blood 120 (18), 3793–3802 (2012).

Liesz, A. et al. Inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking shields the brain against deleterious neuroinflammation after stroke. Brain 134 (Pt 3), 704–720 (2011).

Fowler, A. J. & Agha, R. A. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is related to the severity of coronary artery disease and clinical outcome in patients undergoing angiography–the growing versatility of NLR. Atherosclerosis 228 (1), 44–45 (2013).

Maida, C. D. et al. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: Focus on cardioembolic stroke, background, and therapeutic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(18), 6454 (2020).

Chen, Y. & Ye, M. Risk factors and their correlation with severity of cerebral microbleed in acute large artery atherosclerotic cerebral infarction patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 221, 107380 (2022).

Feng, X. et al. The association between neutrophil counts and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute ischemic stroke according to stroke etiology. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1117408 (2023).

Heikinheimo, T. et al. Preceding and poststroke infections in young adults with first-ever ischemic stroke: Effect on short-term and long-term outcomes. Stroke 44 (12), 3331–3337 (2013).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82371331 and 81971111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y. Fu, X.Y. Shi, C.F. Xing and R.H. Yin made the investigation. X.Y. Fu wrote the main manuscript text, Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8; Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8. X.Y. Fu, X.Y. Shi, R.H. Yin and A.J. Ma polished the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our research program was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University. We previously collected written informed consent from all participants or their next of kin.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, X., Shi, X., Yin, R. et al. The association between variation of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and post-thrombolysis early neurological outcomes in patients with stroke of different TOAST classification. Sci Rep 15, 6517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91334-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91334-z