Abstract

Effective identification of damage characteristics and failure modes for buried pipelines subjected to fault movements is crucial for early design and disaster assessment. In the preceding companion paper, the structural responses of large-diameter prestressed concrete cylinder pipeline (PCCP) subjected to fault displacement were initially investigated under the condition where faulting crosses pipe barrel vertically, and the deterioration process and failure modes were summarized. However, the structural responses of jointed pipelines are closely tied to faulting parameters. In this paper, a study on the location and angle of the fault plane is conducted, and the damage response and failure modes of large-diameter PCCPs are analyzed in detail and compared. The results show that strike-slip fault movement causes pipeline movement through pipe–soil interaction, and the fault displacement is accommodated by several pipe segments for the large diameter-to-length ratio PCCPs. When the fault plane crosses the pipe segment at an acute angle, the primary failure modes include material damage to the pipe joints and barrel, as well as the risk of joint leakage. Material damage occurs at the joint when the fault plane passes through the PCCP joint. Given the mechanical properties and seismic resilience of PCCPs, it is advisable to avoid faulting at acute angles crossing pipeline joints. This work focuses on the structural behavior of segmented composited PCCPs crossing a fault, aiming to predict pipeline damage and failure. The findings contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the failure modes, damage characteristics, and disaster evaluation of PCCPs under strike-slip fault conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Buried pipeline systems, often referred to as “lifeline projections”, are crucial to urban life, as they transport essential materials for daily living and industrial activities. These pipelines form the material foundation of urban infrastructure and perform vital functions, including information transmission, resource dispatching, drainage, disaster mitigation, and waste disposal. It is essential to ensure the integrity and safety of pipelines, even in the event of natural disasters such as earthquakes. In general, underground pipelines are vulnerable to earthquake-induced damage, particularly from permanent ground displacements (PGD) or transient seismic wave propagation1,2,3. The wave propagation hazard is transient and is associated with ground shaking, which induces temporary strains in buried pipelines (strains that dissipate once the shaking ceases). In contrast, the PGD hazard is characterized by a permanent offset along a fault, leading to enduring strains in the buried pipeline (strains that persist even after the shaking stops). Seismic faulting, a principal form of PGD, has been responsible for numerous incidents of pipeline failure and interruptions in functionality4. It is the geological discontinuity resulting from earthquakes where continuous soil or rock mass shifts over another, forming a fault plane between the two blocks.

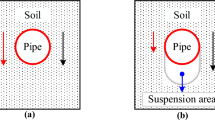

In terms of seismic behavior and design, the most significant difference lies in the connection manner of buried pipelines (Fig. 1). Specifically, for continuous pipelines (where the axial and rotational stiffness of the pipeline joint is comparable to that for the pipe section away from the joint), it has been identified that tensile weld fracture and local buckling failure are the two main failure modes under faulting5,6,7. In seismic investigations of composite pipelines, such as glass-fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) pipes8 and carbon fiber reinforced polymer-based composite pipes (CFRP)9, they are often assumed to behave as shell structures. However, the structural response of segmented pipelines is more complex as the stiffness of the joints is significantly lower than that of the pipe sections away from the joints. The flexible joints can rotate and translate to accommodate ground displacement, partially absorb the deformation, and release the bending moment, thereby reducing pipe damage caused by ground motion10. Due to the seismic resistance of the joints, segmented pipelines have attracted attention in recent years. Based on the assumptions that segments are rigid and joints accommodate the deformation, O’Rourke and Liu proposed a simple mathematical method to evaluate the kinematic response of a buried pipeline subjected to a strike-strip fault1. Furthermore, experiments and simulations have been conducted on different types of segmented pipelines under faulting, including ductile iron pipeline11,12, concrete segmented pipes13,14, vitrified clay pipelines15. However, most of the studies above focused on the homogeneous material pipeline with small diameter-to-length ratios (0.03 for ductile iron pipes12, 0.1 for vitrified clay pipes15, 0.12 for concrete pipes13).

Large-diameter Prestressed Concrete Cylinder Pipelines (PCCPs) are now widely used in large-scale water transfer projects across regions and basins due to their advantages, including excellent anti-seepage and certain seismic performance16,17. It is a segmented and composited rigid pipeline connected through bell-and-spigot joints and consisting of concrete, mortar coating, steel cylinder and prestressing wires (see Fig. 2). As large-diameter (with a diameter-to-length ratio of 0.76 in this study) and high-pressure water delivery systems, failures can lead to disastrous and catastrophic consequences, with significant impacts over a large area18,19. Consequently, it is of great urgency to ensure the structural safety of PCCP in its full lifecycle. From a lifecycle perspective, the factors that can lead to damage and failure in PCCPs are generally categorized into three groups: design and manufacturing, construction and operation, internal and external environmental factors20,21. Nevertheless, as buried PCCPs traverse complex geological conditions, pipe failure due to poor pipe–soil interaction has often been overlooked, which often leads to serious consequences. Therefore, the structural response and damage mechanisms of PCCPs under complex geological conditions deserve more attention to ensure safety. Ge and Sinha22 first analyzed the effect of various bedding conditions on the structural integrity of PCCP, emphasizing the importance of proper bedding conditions. Considering interface interactions and combined loads under unfavorable geological conditions, the pipe response and failure analysis of PCCP were further investigated23,24. These studies highlighted the importance of good bedding conditions and provided invaluable insights into damage progression under even geological disasters. Given the challenges of conducting laboratory tests on large-diameter PCCP under tectonic fault displacement, numerical simulation analysis offers significant advantages in predicting deterioration under ultimate loads25.

In the earlier companion paper26, the structural response and failure analysis of large-diameter PCCPs subjected to strike-slip fault displacement were conducted under the condition that the fault crosses the middle of the pipe barrel vertically. However, faulting parameters, such as the location and angle of the fault plane are apparently the most significant factors influencing the failure modes and deterioration processes observed in pipelines27,28,29. This paper focuses on these faulting parameters. In this study, the analysis methods of the interaction between PCCP and soil are reviewed first. Considering soil–pipe and pipe–pipe interactions, the structural damage and failure modes of large-diameter PCCP under different fault locations and angles are investigated through both simplified equivalent and detailed FE models. The innovative papers basically reveal the structural responses and failure modes of large PCCPs subjected to strike-slip fault movements. The results provide the research community and pipeline engineers with a deeper understanding of the damage characteristics and failure modes, which will inform failure prediction and major disaster prevention.

Pipeline–soil interaction

The buried pipeline is constrained by the surrounding soil/rock and moves in response to the movement of the surrounding media. Ground displacements caused by earthquakes often result in significant structural damage and even catastrophic consequences with a far-reaching impact due to the interaction between the pipe and the soil. Hence, accurate evaluation of pipe performance depends on a proper understanding of pipe–soil interaction. Three primary research methodologies exist for pipe–soil interaction: analytical30,31, experimental32,33 and computational simulation34,35,36. Additionally, the finite element (FE) method offers distinct advantages and is a crucial tool for investigating buried pipelines, as it can simulate the in-situ stress conditions and pipe performance under fault-crossing scenarios37,38,39,40. Although the models (beam41/shell42/beam-shell43) on the Winkler foundation are frequently utilized in the literature for preliminary design and analysis of large-scale pipeline systems due to their simplicity and computational efficiency, the 3D soil continuum method is better suited for capturing advanced pipeline–soil interaction. This method can incorporate different continuum soil constitutive models and study behaviors subjected to permanent earthquake-induced actions40,44. In this process, the soil–pipe interface is typically modeled using a surface-to-surface contact model, which considers the behavior in both the tangential and normal directions. An advanced hard contact interaction was used to simulate the normal behavior, allowing for separation between the interfaces. The penalty function approach is employed to describe the interface tangential friction, with a suitable friction coefficient used to describe the interaction45. Given the focus on studying the ultimate failure state of the PCCP, a computationally efficient elastic soil constitutive model was adopted, with the friction coefficient set to 0.3 for the soil–pipe interaction.

In conventional installations, the soil layer around the PCCP can be divided into two layers: the bedding soil and the backfill soil, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The bedding layer is the soil placed beneath the pipe, while the backfill layer is the soil placed around and above the pipe to provide a stable and supportive environment. Specifically, the outer surface of PCCP and the inner surface of the surrounding soil serve as the interfaces of pipeline–soil interaction with the former one as the master surface due to its greater stiffness. The stiffness of the surrounding soil, along with the characteristics of the soil–pipe interaction, influences the load-carrying capacity as well as the deterioration process of pipes46. The soil parameters used in this study are listed in Table 1 below.

Three-dimensional modeling of buried PCCP

Nonlinear finite element analysis using ABAQUS software was widely used for structures analysis in civil engineers47. It was employed to simulate the behavior of buried in-service PCCP subjected to strike-slip fault movement. According to the calculation formula for the relative rotation of joints1, when a fault crosses the pipe barrel, the relative rotation of the joint is greater than that when it crosses the pipe joint. Furthermore, the fault displacement with an acute angle of the moving soil block can be decomposed in the vertical component and the horizontal component. The horizontal component mainly causes longitudinal movement and axial extension, which is more likely to cause tensile damage for concrete. The more unfavorable condition, where the plane crosses the pipe barrel at an acute angle of 45°, is thus analyzed, as cracking in the concrete core and mortar layer is the initial manifestation of PCCP damage. Given the trade-off between accuracy and computational expense, the affected length of the pipeline under different fault locations and angles was determined first through a simplified equivalent model. Subsequently, a detailed PCCP model was developed to simulate the conditions of pipeline under strike-slip fault movement. The basic parameters and the implementation process are described in this section.

Model length determination

Buried segmented PCCP spans long distances and consists of several materials. It is essential to determine an approximate effective length of PCCP under strike-slip FD, considering the high computational cost of simulations. To address this, equivalent simplified models were proposed to find the affected optimal model length23. The parameters of the embedded PCCP studied (inside diameter D = 3.8 m, working pressure P = 0.6 MPa, single pipe length L = 5 m and buried depth H = 2.5 m) were selected from an urban pressure water diversion project, and its geometric and material parameters are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The equivalent model simplified the PCCP of multilayer pipe wall into a single material by four indexes (Fig. 4), namely: the same geometrical size, material density, section stiffness and prestress value, for the trial calculation to determine the optimal affected model length. As a result, the same circumferential deformation, especially the rotation angle of joints, is the same as the original structure, thereby enabling an assessment of the optimal affected response range of the pipeline under soil movement. The calculation of the stiffness is provided in Table 4, and the equivalent elastic modulus is 36,273 MPa. The prestress is applied to the equivalent model using the equivalent external radial pressure method48,49, and the calculated prestress value is 1.35 MPa.

A finite element model of the equivalent pipeline with its surrounding soil medium was established on the basis of the equivalent pipe parameters. To minimize the influence of boundary conditions, the whole model dimensions were set to 38 m (10D) and 19 m (5D) in the X and Y directions, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5. The longitudinal length was set to 115 m (23 L) with the case of an acute fault angle, taking into account the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy. The bottom was restrained against movement in the X, Y and Z directions, the top surface of the soil was unconstrained as a free surface, and the others were restrained against their normal directions. The soil blocks under the fault offset were split into two volumes (soil blocks) interacting along the fault plane, and the interaction between the soil blocks was stated as contact surfaces7. The loads were applied in two stages: the first stage was the application of pipeline operating load, and the second stage was the strike-slip fault movement. Since the velocity of movement on one side of the fault with respect to the opposite side is generally sufficiently low, the movement of the fault was achieved by applying static displacement. The surface-to-surface contact model is defined to simulate the interaction between the bell end and spigot end, considering the behavior in the tangential and normal directions, available in ABAQUS24. The finite element implementation process follows the process outlined in previous literature26 and will not be repeated here. For consistency and continuity of the researches, the determined modeled length of the PCCP was made up of 9 pipes when the fault crossed the pipe barrel at an acute angle, and 8 pipes when the fault passed through the pipe joint.

Detailed layered PCCP model

The finite element analysis model of long-distance buried PCCP consisted of two parts: the pipeline and the surrounding confined soil. Based on the determined pipeline length, a detailed layered PCCP model was developed for the affected area (comprising 8 ~ 9 pipe segments and joints) along with its surrounding soil. The PCCP was modeled in layers and constrained by interlayer interaction. The stress–strain behavior of each material is modeled based on the design standard for PCCP (AWWA C304-2014)47. When tensile strain of concrete reaches 1.5\({\varepsilon _t}\), microcracks appear, and visible cracks are generated at 11\({\varepsilon _t}\). For mortar, microcracks appear at 6.4\({\varepsilon _{tm}}\), and visible cracks are generated at 8\({\varepsilon _{tm}}\), where \({\varepsilon _t}\) and \({\varepsilon _{tm}}\)represent the peak tensile strains for concrete and mortar, respectively. The modeling process follows that of previous studies and has been described in detail elsewhere26. In the first stage, 9 steps were applied to simulate the operational state of the pipeline, including the prestress, gravity, fluid gravity, backfill weight, internal water pressure and groundwater (the groundwater level was assumed to be flush with pipe crown); In the second stage, the strike-slip fault displacement load was applied by steps until failure occurred. The numbering of the pipe segments and joints is shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The overall FE model with the fault plane crossing the joint after meshing is shown in Figs. 7a and b.

Results analysis

In this section, the structural responses are analyzed for different locations and angles at which the strike-slip fault plane intersects the pipe. Furthermore, the damage behavior and failure mode are summarized and compared. The limit-state method is used to evaluate the PCCP state by assessing the stress and strain conditions of each material50,51. Based on the stress-strain curves, the threshold tensile damage to concrete core is 116µε for microcracks and 847µε for visible cracks50.

Pipeline response with an acute faulting angle

Displacements and rotation angles of the pipeline

When the strike fault plane crosses the segmented pipeline at an acute angle, it causes lateral and axial displacements due to pipe–soil interaction, and the motion in each direction increases proportionally to the magnitude of the fault displacement. As shown in Fig. 8, the maximum lateral and axial displacement of the pipe in the moving block is 10.6 cm when the fault displacement reaches 15 cm. The pipe segments in the vicinity of the fault plane are more susceptible, while those further away are less affected. When the fault plane passes through the midpoint of a pipe barrel (#5 pipe), the lateral and axial displacements of #4~#6 pipes are significantly affected, with the maximum relative displacement occurring in the #5 pipe (see Fig. 8). Transverse movement of the pipeline can alter the angle of the joints and the relative angle between the pipes, while axial movement can result in the joints pull-out, both of which increase the risk of leakage at the spigot and bell joints and pose a threat to the operational safety of the segmented pipeline. Accordingly, when the pipeline is intersected at an acute angle by a fault plane, it is crucial to monitor the relative angles of the pipe joints and the axial pull-out displacement of the most vulnerable joint (joint E) under varying fault displacements.

Figure 9a shows the relative rotation angle of joints due to the lateral movement of the pipeline. The values are approximately symmetric with respect to the fault plane, which acts as the center. The joints closest to the fault plane (joint D and joint E) are the most significantly affected by the fault displacement (FD), which is consistent with the experimental results for segmented concrete pipes14. As the displacement increases to 15 cm, the maximum relative angle approaches the limit angle specified in the standard (0.5°)52, indicating a risk of leakage as FD continues to increase. Figure 9b shows the axial pull-out distance of joint E, which increases gradually with the rise in FD. When FD reaches 18 cm, the axial pull-out distance of the joint reaches approximately 5 cm, thereby reducing the sealing effectiveness of the spigot-and-bell connection of the PCCP.

Structural damage response

PCCP is a composite pipe and its integrity depends on the material strength of each layer. The concrete core serves as the primary bearing layer, and its cracking is an indicator of deterioration. Figures 10 and 11 illustrate the damage to the concrete core caused by strike-slip fault movement. When the FD reaches 3 cm, the maximum principal strain of concrete at the end of the joint E has exceeded the microcrack limit, indicating the serviceability limit state. Subsequently, the damaged area of microcracks expands and deepens with the increasing FD, and the microcracks begin to appear on the invert and crown as the displacement increases to 5 cm. By the time FD reaches 10 cm, the microcrack area on the concrete has extended to the pipe crown, invert and waist. Additionally, the maximum principal strain on the inner bell side of joint E has exceeded the threshold for visible cracking, as shown in Fig. 11. Unlike the vertical passage of the fault plane through the pipeline, the concrete damage to the pipe joint appears first, followed by material damage to the pipe barrel (the crown/invert of the outer core and the springline of the inner core) when the fault plane at an acute angle. Furthermore, the crack damage expands and deepens as FD increases, resulting in a reduction in the bearing capacity of the concrete core. Subsequently, the steel cylinder and prestressing wires play a more significant role in load-bearing, and the material layers gradually degrade. In other words, the multi-layer composite PCCP offers a significant structural advantage as it reaches its limit states sequentially under adverse conditions.

When the tensile crack damage occurs on the concrete core, the steel cylinder and prestressed steel wire bear the load, resulting in an increase in stress. At an FD of 10 cm, the steel cylinder reaches the yield strength (the crossed pipe segment and its connected joints are the most obvious damage location), indicating that the PCCP reaches the elastic limit state (Fig. 12a). Additionally, the yield zone of the steel cylinder first appears at the waist of the pipe crown, invert and joint E, while the prestressed steel wires have not yet reached their material strength at this point (see Fig. 12b).

With the increasing of FD, the yield range of the steel cylinder expands, and the stress in the prestressing wire also increases. As the displacement reaches 18 cm, the cylinder exceeds its yield strength (235 MPa) over a large area at the pipe crown, invert and springline. At this point, the maximum stress in the prestressing steel wires at the pipe crown and invert have reached the yield strength (0.85 times the ultimate strength), and the PCCP reaches its strength limit state, as shown in Fig. 13.

In summary, strike-slip faulting with an acute angle crossing the pipe segment can cause both lateral and axial displacement of the segmented pipeline. Furthermore, the relative angle between the pipes caused by the lateral displacement and the joint pull-off caused by the axial displacement both place the PCCP under unfavorable operating conditions. Under the action of FD, the micro-crack first appears in the inside concrete core of spigot end, leading to a reduction in the structural load-bearing capacity. As displacement increases, the extent and depth of the concrete damage is amplified, and at the same time the microcracks develop into visible crack damage. Once there is sustained damage to the concrete core, the steel cylinder and steel wire will take the load and then in turn reach their material yield strength as FD increases, ultimately leading to PCCP failure. Therefore, the damage characteristics can be summarized as follows: joint material damage, pipe barrel material damage, excessive corner and axial pull-off leading to joint leakage risk.

Pipeline response with the fault crossing the pipe joint

Joints are important components of segmented pipelines, and the unique spigot-and-bell joint of PCCP allows the pipeline to accommodate a certain amount of lateral or vertical movement during installation and operation, reducing the damage to the pipe material. In this section, the structural damage to PCCP caused by a fault crossing the pipe joint vertically is analyzed. The number of pipe segments and joints is illustrated in Fig. 7 (“Detailed layered PCCP model” section).

Rotation angles of the pipeline

Based on the analysis above, the relative angle of the pipe joint due to the transverse movement of the pipeline can alleviate the bending moment, mitigating damage to the pipe material. Figure 14 illustrates the relative angle of pipeline joints when the fault plane crosses the pipe joint (joint D). As shown, the joints most affected (joints C and E) are adjacent to the crossing joint, while the impact on the others is minimal. When the FD is 15 cm, the relative rotation angle of pipe joint E is the largest (approximately 0.28°), but it does not exceed the critical angle. In contrast, the relative rotation angle at the intersection of the fault plane (joint D) is minimally affected, indicating that the shear and bending moments caused by the pipe–soil interaction lead to the material damage at the location where the fault plane traversed under the movement of the strike-slip fault. The material damage and subsequent failure behavior are analyzed in the next section.

Damage response and failure process

The pipe material damage is shown in Figs. 15 and 16 when the strike-slip fault crosses the pipe joint vertically. In this case, the outer concrete core of joint D has obvious micro-crack damage at a fault displacement of 3 cm, indicating the serviceability limit state (see Fig. 15a). As the displacement increases, the crack region deepens and extends further. When the FD reaches 5 cm, the concrete damage at the joint evolves into visible cracks (Fig. 15b) and a significant range of crack damage occurs in the mortar protective layer (Fig. 16b). Concurrently, the steel cylinder reaches its material yield strength and marks the elastic limit state of PCCP (Fig. 16a). As the fault displacement gradually increases to 10 cm, the yield range of the steel cylinder is further extended and the prestressed steel wire reaches its yield strength (85% of the ultimate strength), indicating the strength limit state. Consequently, the material damage at the crossing point and its progression to failure represent the evolution of the PCCP from damage to failure as the fault passes vertically through the pipe joint.

In summary, when the fault plane passes vertically through the joint of PCCP, the pipe–soil interaction resulting from fault displacement leads to significant material damage at the pipe joint. Even a small amount of fault displacement can cause crack damage to the pipe material, followed by the yielding of the steel cylinder and prestressed steel wire as the displacement increases. Ultimately, the PCCP fails after reaching the strength limit state. At this point, the relative angle between pipes due to pipeline movement is quite small, there is still a considerable margin before reaching the limit angle specified in the standards. In other words, the risk of pipeline failure due to material damage at the pipe joint is much greater than the risk of leakage caused by the relative angle between pipe segments.

Comparative of the damage characteristics and failure modes

The buried pipeline runs under loads and is constrained by the surrounding soil. As a result, the segmented PCCP moves due to pipe–soil interaction suffering from the soil fault dislocation. The pipeline movement causes the relative angle of the joint and the material damage to the pipe barrel. As the fault displacement increases, the PCCP gradually reaches its limit states. Due to the bell-and-spigot joint, the influence of the fault movement gradually decreases in the direction away from the fault plane. More importantly, the fault parameters (angle, position and displacement) significantly influence the structural response. Based on the results, this section compares the effects of fault parameters on pipeline damage characteristics and failure modes (see Fig. 17).

When the fault plane intersects the pipe barrel vertically, it causes the transverse movement of the pipeline and the further relative angle of pipe joints. As a result, the primary forms of pipeline damage are the material damage caused by the axial force and the leakage risk of the joint and its material damage caused by the relative angle. The damage process can be summarized as follows: extensive material damage to the pipe barrel, excessive joint angle, failure of the pipe barrel, and crushing and stacking of the joints26.

When a strike-slip fault plane through the pipe barrel at an acute angle, the resulting movement can be decomposed into transverse and axial components, both of which present adverse conditions for composite segmented PCCP pipelines. The transverse movement causes the relative angle between pipe segments, while the axial one leads to dislocation of the pipe joint. When the FD is 3 cm, micro-crack damage appears in the inner concrete core of the joint, indicating that the PCCP has reached its serviceability limit state. As displacement increases to 10 cm, the micro-cracks at the joint evolve into visible crack damage, and the micro-cracks form on the middle of the concrete of the pipe barrel. Simultaneously, the steel cylinder at both the joint and the crown of the pipe barrel reaches its yield strength, suggesting the elastic limit state. When the displacement reaches 18 cm, more visible crack damage is observed in the concrete of both the pipe barrel and the joint. Additionally, the steel cylinder reached yield strength in a large area at both the crown of the pipe barrel and the joint, while the prestressing steel wires also reach their yield strength, marking the strength limit state of PCCP. In summary, the main damage forms are material damage to both the pipe segment and joint, along with the risk of extrusion and axial pull-out of the pipe joint. The damage failure process can be summarized as follows: material damage to the pipe joint, material damage to the pipe barrel, and risk of the joint leakage due to excessive angle and axial pull-out.

When the fault plane intersects the joint of the PCCP vertically, the main damage form is material damage failure of the joint. Micro-cracks appear in the concrete core of the pipe joint when the fault displacement reaches 3 cm, indicating the serviceability limit state of the PCCP. As the displacement increases to 5 cm, extensive cracks expand on the mortar protective layer and concrete core; meanwhile, the steel cylinder locally reaches its yield strength. As displacement increases further to 10 cm, the yield range of the steel cylinder expands, and the steel wires reach the yield strength, marking the strength limit state. Therefore, when the fault plane crosses the joint of the segmented PCCP pipeline, the material damage at the bell-and-spigot joint and its continuous aggravation is the failure process.

Conclusions

Finite element models of buried large-diameter PCCP subjected to strike-slip fault were established to analyze the effects of the fault parameters on damage characteristics and failure process. Fault displacement causes movement of the buried pipeline, and the displacement is accommodated by several pipe segments due to the large diameter-to-length ratio of PCCP. As FD increases, material damage occurs sequentially across the multilayered PCCP, and the pipe gradually reaches its limit states. The damage characteristics and failure process of the buried segmented composite PCCP under fault movement are closely related to both the crossing angle and position of the fault plane. Regarding the strength limit state, the FD is18 cm when the fault plane crosses the pipe barrel at an acute angle, while it is 10 cm when the fault plane crosses the pipe joint vertically.

When the fault plane intersects the pipe barrel at an acute angle, it can result in both transverse and axial displacement. The transverse movement may cause relative rotation of the joints, while axial displacement can lead to joint pull-out. The failure process can be summarized as follows: joint material damage, pipe barrel material damage, excessive corner and axial pull-off leading to joint leakage risk. When the fault plane passes through the joint vertically, the unique advantages of the bell-and-spigot joint with an interspace cannot be fully utilized. Consequently, the main damage form is material damage to pipe joint due to the shear and bending moments induced by pipe–soil interaction, and its continuous aggravation is the failure process as fault displacement increases. In contrast to vertical crossing of the pipeline, a sharp-angled crossing of the fault plane can cause more severe damage to the pipeline. Moreover, compared to crossing the pipe joint, the relative freedom of movement in a segmented pipeline allows for better release of bending moments, thereby reducing material damage to the pipe when the fault plane crosses the pipe barrel. Therefore, to optimize the mechanical performance and seismic resilience of the concrete pipeline, it is advisable to avoid acute-angle fault plane crossings at the pipeline joints whenever possible.

This paper supplemented and improved the structural failure analysis of PCCP subjected to strike-slip fault motion. The reliable prospective and predictive findings offer valuable insights into the failure modes and deterioration processes of composite PCCP under strike-slip fault conditions. These findings can serve as a reference for emergency response strategies and structural safety assessments. Still, a comparison to experimental results of full-scale physical testing from multiple perspectives or real event data is needed for the final verification. In the future, it is also worthwhile to focus on and study the structural performance of PCCP during long-term operation, including the effects of factors such as material aging and corrosion.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

O’Rourke, M. J. & Liu, J. X. Monograph MCEER-12-MN04. (ed Buffalo) (Multidisciplinary Center for Earthquake Engineering Research, NY, USA, 2012)

Vazouras, P., Dakoulas, P. & Karamanos, S. A. Pipe-soil interaction and pipeline performance under strike-slip fault movements. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 72, 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2015.01.014 (2015).

Shi, P. Seismic wave propagation effects on buried segmented pipelines. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 72, 89–98 (2015).

Liang, J. & Sun, S. Site effects on seismic behavior of pipelines: A review. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 122, 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1285974 (2000).

Ni, P., Moore, I. D. & Take, W. A. Numerical modeling of normal fault-pipeline interaction and comparison with centrifuge tests. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 105127–105138 (2018).

Banushi, G., Squeglia, N. & Thiele, K. Innovative analysis of a buried operating pipeline subjected to strike-slip fault movement. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 107234–107249 (2018).

Trifonov, O. V. Numerical stress-strain analysis of buried steel pipelines crossing active strike-slip faults with an emphasis on fault modeling aspects. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. 64014008 (2015).

Rafiee, R. & Habibagahi, M. R. On the stiffness prediction of GFRP pipes subjected to transverse loading. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 22(11), 4564–4572 (2018).

Soveiti, S. & Mosalmani, R. Mechanical behavior of buried composite pipelines subjected to strike-slip fault movement. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 135, 106195 (2020).

Xu, M., Shen, D. & Rakitin, B. The Longitudinal response of buried large-diameter reinforced concrete pipeline with gasketed bell-and-spigot joints subjected to traffic loading. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 64 117–132 (2017).

Qin, X., Wang, Y. & Fu, C. Joint kinematics and sealing capacity assessment of ductile iron pipes under abrupt transverse ground movements. Can. Geotech. J. 59(3), 342–358 (2021).

Wham, B. P. & O’Rourke, T. D. Jointed pipeline response to large ground deformation. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 7(1), 04015009 (2016).

Pour-Ghaz, M. et al. Using electrical, magnetic and acoustic sensors to detect damage in segmental concrete pipes subjected to permanent ground displacement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 33749–33762. (2011).

Kim, J. et al. Assessment of the behavior of buried concrete pipelines subjected to ground rupture: Experimental study. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 3(1), 8–16 (2011).

Qin, X. & Ni, P. Kinematics of bell-spigot joints in vitrified clay pipelines under differential ground movement. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 91, 103005 (2019).

Zhang, H. Y., Peng, H. & Chen, X. The development of prestressed concrete cylinder pipe in China. Appl. Mech. Mater. 580, 2363–2366 (2014). https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.580-583.2363

Higgins, M. S., Stroebele, A. & Zahidi, S. Numbers don’t lie, PCCP performance and deterioration based on a statistical review of a decade of condition assessment data. Pipelines 2012: Innovations in Design, construction, operations, and maintenance, doing more with less. ASCE 298–306 (2012).

Williams, A. F., Pruitt, E. R. & Livermore, M. J. From pilot to permanent: Evolution of LWC’s PCCP condition assessment program. Pipelines 2012: innovations in design, construction, operations, and maintenance-doing more with less 307–318 (ASCE, Miami Beach, Florida, 2012).

Shenkiryk, M., Klein, B., Stroebele, A. & Franchuk, S. Tucson Water’s Homegrown condition assessment of PCCP. Pipelines 2014: From Underground to the Forefront of Innovation and Sustainability 146–158 (ASCE, 2014).

Ge, S. & Sinha, S. Failure analysis, condition assessment technologies, and performance prediction of prestressed-concrete cylinder pipe: State-of-the-art literature review. J. Perform. Constr. Fac. 28(3), 618–628 (2014).

Romer, A. E., Ellison, D., Bell, G. E. C. & Clark, B. Failure of Prestressed Concrete Cylinder Pipe (AWWA Research Foundation, 2007).

Ge, S. & Sinha, S. Effect of various bedding conditions on structural integrity of prestressed concrete cylinder pipe. J. Mater. Sci. Res. 4, 34–44. https://doi.org/10.5539/jmsr.v4n2p34 (2015).

Feng, X., Li, H., Chen, B., Zhao, L. & Zhou, J. Numerical investigations into the failure mode of buried prestressed concrete cylinder pipes under differential settlement. Eng. Fail. Anal. 111, 104492 (2020).

Li, Y., Li, W., Wen, L., Li, Y. & Li, K. The longitudinal response of prestressed cylinder concrete pipe with bell spigot joints. Struct. Concrete 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202100553 (2021).

Hajali, M. & Abi Shdid, C. Using numerical modeling for asset management of buried prestressed concrete cylinder pipes. Struct. Concrete 22(3), 1487–1499. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202000238 (2021).

Li, H., Feng, X. & Zhao, L. Failure analysis of a buried large-diameter prestressed concrete cylinder pipeline subjected to strike-slip fault displacement. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 121, 104334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104334 (2022).

Qin, X. & Wang, Y. Different failure modes assessment of bell-spigot jointed ductile iron pipes under abrupt transverse ground movements. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 163107558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2022.107558 (2022).

Chen, Q., Ni, P. & Qin, X. Numerical investigation on failure modes of bell-spigot jointed ductile iron pipelines subjected to dip-slip faults with different dip angles. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 133, 104982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2023.104982 (2023).

Valsamis, A. I., Bouckovalas, G. D. & Gantes, C. J. Alternative design of buried pipelines at active fault crossings using flexible joints. Int. J. Pres. Ves Pip. 180, 104038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpvp.2019.104038 (2020).

Chan, P. D. & Wong, R. C. Performance evaluation of a buried steel pipe in a moving slope: A case study. Can. Geotech. J. 41, 894–907. https://doi.org/10.1139/t04-035 (2004).

Cocchetti, G., di Prisco, C., Galli, A. & Nova, R. Soil–pipeline interaction along unstable slopes: A coupled three-dimensional approach. Part 1: Theoretical formulation. Can. Geotech. J. 46(11), 1289–1304. https://doi.org/10.1139/T09-02 (2009).

Kim, J. et al. Behavior of full-scale Concrete Segmented Pipelines Under Permanent Ground Displacements. Health Monitoring of Structural and Biological Systems 257–267 (SPIE, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1117/12.847735

Munro, S. M., Moore, I. D. & Brachman, R. W. I. Laboratory testing to examine deformations and moments in fiber-reinforced cement pipe. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. 135, 1722–1731. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000142 (2009).

Zhang, C., Zhu, H., Zhang, W., Li, H. & Liu, W. Modeling uplift failure of pipes buried in sand using material point method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 119, 104203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104203 (2022).

Valizadeh, H. & Ecemis, N. Soil liquefaction-induced uplift of buried pipes in sand-granulated-rubber mixture: numerical modeling. Transp. Geotech. 33, 100719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2022.100719 (2022).

Meidani, M., Meguid, M. A. & Chouinard, L. E. Evaluation of soil-pipe interaction under relative axial ground movement. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. 8, 04017009. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)PS.1949-1204.0000269 (2017).

Joshi, S., Prashant, A., Deb, A. & Jain, S. K. Analysis of buried pipelines subjected to reverse fault motion. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 31, 930–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2011.02.003 (2011).

Özcebe, A. G., Paolucci, R. & Mariani, S. Numerical modeling of the interaction of pressurized large diameter gas buried pipelines with normal fault ruptures. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 101, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2017.07.017 (2017).

Gawande, K., Kiran, R. & Cherukuri, H. P. A numerical study of the response of buried steel pipelines undergoing strike-slip fault. Eng. Fail. Anal. 102, 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2019.04.026 (2019).

Zhang, R., Gomaa, S. M. M. H., Hussein, M., Zayed, T. & Meguid, M. Review of numerical approaches used in soil-pipe interaction analysis of water mains. Transp. Geotech. 42, 101008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.101008 (2023).

Saberi, M., Arabzadeh, H. & Keshavarz, A. Numerical analysis of buried pipelines with right angle elbow under wave propagation. Proc. Eng. 14, 3260–3267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2011.07.412 (2011).

Dadfar, B., Hesham El Naggar, M. & Nastev, M. Ovalization of steel energy pipelines buried in saturated sands during ground deformations. Comput. Geotech. 69, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2015.05.004 (2015).

Saberi, M., Behnamfar, F. & Vafaeian, M. A semi-analytical model for estimating seismic behavior of buried steel pipes at bend point under propagating waves. B Earthq. Eng. 11, 1373–1402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10518-013-9430-y (2013).

Saberi, M., Annan, C. & Sheil, B. B. An efficient numerical approach for simulating soil-pipe interaction behaviour under cyclic loading. Comput. Geotech. 146, 104666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104666 (2022).

Sarvanis, G. C. et al. Permanent earthquake-induced actions in buried pipelines: numerical modeling and experimental verification. Earthq. Eng. Struct. D 47, 966–987. https://doi.org/10.1002/eqe.3001 (2018).

Zamanian, S., Hur, J. & Shafieezadeh, A. A high-fidelity computational investigation of buried concrete sewer pipes exposed to truckloads and corrosion deterioration. Eng. Struct. 221, 111043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111043 (2020).

Mostafaei, H., Mousavi, H. & Barmchi, M. A. Finite Element Analysis of Structures by ABAQUS: For Civil Engineers (Simay-e-Danesh Publication, 2023).

Zarghamee, M. S., Eggers, D. W. & Ojdrovic, R. P. Finite-element modeling of failure of PCCP with broken wires subjected to combined loads. Pipelines. In Beneath Our Feet: Challengers and Solutions-Proceedings of the Pipeline Division Specialty Conference 1–17 (American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Cleveland, United States, 2002).

Zarghamee, M. S., Ojdrovic, P. & Dana, W. R. Coating delamination by radial tension in prestressed concrete pipe. II: Analysis. J. Struct. Eng. 119, 2720–2732 (1993).

AWWA. Standard for Design of Prestressed Concrete Cylinder Pipe. ANSI/AWWA C304 (CO, 2014).

Cheng, B. et al. Mechanical properties and loading response of prestressed concrete cylinder pipes under internal water pressure. Eng. Struct. 216, 110674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.110674 (2020).

China, S. P. O. Prestressed Concrete Cylinder Pipe. GB/T19685–2017 (Beijing, 2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52079024) and the Scientific Research Program for the Talent of XIHUA University (Grant No. RX2300000879).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L.: Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Visualization. X.F.: Resources, Writing—review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. S.C.: Writing, Prepared figures. K.S.: Visualization, Reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Feng, X., Chen, S. et al. Structural behavior of large diameter prestressed concrete cylinder pipelines subjected to strike-slip faults. Sci Rep 15, 7560 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91442-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91442-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Optimized seismic risk mitigation in pipeline routing using a metaheuristic GIS based approach

Scientific Reports (2025)