Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a glucose metabolism disorder with an unclear etiology that occurs specifically during pregnancy. While elevated serum ferritin levels have been reported to increase the risk of GDM, these findings lack validation in large-scale studies and have yet to inform clinical practice effectively. This study enrolled 12,434 controls and 3599 GDM patients and employed binary multifactorial logistic regression, restricted cubic spline, propensity score matching, and a random forest algorithm to explore the relationship between serum ferritin and GDM, as well as the effect size of ferritin on GDM. The results indicated that GDM patients have higher serum ferritin levels compared to controls in the second and third trimesters. A weak correlation was found between serum ferritin levels and OGTT 1-hour and 2-hour blood glucose levels in the second trimester. Logistic regression (LR) and restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses showed a significant positive correlation between serum ferritin levels and GDM in the second and third trimesters. Propensity score matching analysis indicated that the association between second-trimester serum ferritin levels and GDM remained nearly constant before and after matching. The random forest algorithm suggested that among all confounders, serum ferritin had a minimal effect on GDM risk. In conclusion, our study provides further compelling evidence for the association between serum ferritin levels and gestational diabetes mellitus. However, additional research is still needed to clarify the specific mechanisms underlying this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Iron is a vital trace element essential for various life-sustaining processes, including electron transfer, oxygen transport, and cell proliferation, and its deficiency can result in anemia, fatigue, anorexia, cardiomegaly, and other organ dysfunctions1. Some studies have reported that iron deficiency affects approximately one-third of pregnant individuals worldwide and can increase the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, cognitive dysfunction, and immune dysfunction in the offspring2. Ferritin serves as a stable form of iron storage in the body, which is less affected by short-term dietary changes and other factors3. Although ferritin may not accurately reflect iron metabolism in the presence of infection or inflammation, it remains the preferred indicator for assessing iron status, according to current guidelines and expert consensus4. Currently, there remains significant disagreement among major global medical institutions regarding the threshold levels of ferritin required to diagnose iron deficiency. Nevertheless, most guidelines still recommend using serum ferritin concentrations below 15 µg/mL or 30 µg/mL as the diagnostic criteria for iron deficiency. Serum ferritin levels below 30 µg/mL are commonly used to diagnose iron deficiency during pregnancy, as studies have shown that when serum ferritin falls below 25–40 µg/L, stainable iron in the bone marrow becomes undetectable5,6,7,8. As concerns over iron deficiency arise, excessive serum ferritin may also interfere with glucose and lipid metabolism, which could be the underlying mechanism linking high serum ferritin levels to fatty liver disease9and type 2 diabetes10.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a glucose metabolism disorder that typically occurs during pregnancy, affecting approximately 9–21% of pregnancies worldwide, and can result in various adverse outcomes, including macrosomia and shoulder dystocia11. Its pathogenesis remains unclear, but current evidence suggests that disturbances in intestinal flora, gestational age, multiple pregnancies, conception via assisted reproductive technology, and genetic factors are all associated with an increased risk of GDM12. In recent years, several small population-based studies have suggested that high serum ferritin levels during pregnancy may increase the risk of developing GDM13,14. Corrections of low serum ferritin levels during pregnancy have been demonstrated to mitigate adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with iron deficiency15. However, given the limited sample sizes in existing literature and frequent omission of prior gestational diabetes history and family diabetes history when adjusting for confounders, this may yield biased findings. Therefore, it is particularly crucial to conduct studies with larger population samples to clarify the association between serum ferritin levels during pregnancy and gestational diabetes.

This study aimed to retrospectively analyze patients with GDM and healthy pregnant individuals who underwent prenatal care and delivered at West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University between May 2021 and December 2023. The objectives were to (1) Assess the association between serum ferritin levels and the risk of GDM across pregnancy trimesters. (2) Examine the relationship between serum ferritin levels and glucose metabolism in the second trimester. (3) Explore the association between serum ferritin levels and GDM while adjusting for potential confounders.

Materials and methods

Study design

This study is a retrospective case-control analysis. The diagnostic criteria for GDM were fasting blood glucose ≥ 5.1 mmol/L, 1-hour post-glucose ≥ 10.0 mmol/L, and 2-hour post-glucose ≥ 8.5 mmol/L16. And controls were defined as subjects who had no pre-existing medical or surgical conditions prior to pregnancy and did not develop any pregnancy-related complications throughout the entire gestational period. We included all GDM patients and normal pregnant individuals who received prenatal care and delivered at West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University between May 2021 and November 2023. Initially, 34,682 subjects were enrolled. After excluding individuals with coexisting internal or surgical diseases and abnormal blood pressure or bile acid levels, 3599 GDM patients and 12,434 normal pregnant individuals were included in the final analysis. Additionally, we still examined the association between serum ferritin levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Diagnostic criteria, inclusion and exclusion criteria

The 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is a comprehensive method for assessing glucose metabolism and pancreatic function, providing insights into insulin secretion and glucose metabolism following food intake17. In this study, all participants underwent at least one time of 75 g OGTT between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. High-risk individuals, such as those who were overweight or obese before pregnancy, had a history of gestational diabetes, or a family history of diabetes, underwent additional screenings.

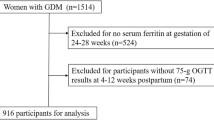

We categorized GDM patients and healthy pregnant individuals without any diagnosed diseases into the GDM group and the normal pregnancy control group, respectively, based on their discharge diagnoses. All participants had a gestational age at delivery of more than 28 weeks. The exclusion criteria included pre-existing or pregnancy-induced hypertension, viral hepatitis, intrahepatic cholestasis, pre-pregnancy diabetes, autoimmune disorders, renal insufficiency (confirmed by at least two tests), hepatic insufficiency (confirmed by at least two tests), and a history of malignancy. The screening and data analysis process are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Diagnostic criteria for anemia and iron deficiency

In this study, iron deficiency was defined as a serum ferritin level ≤ 30 µg/mL (measured by chemiluminescent immunoassay) at any stage during pregnancy18. Gestational anemia was defined as a hemoglobin concentration below 120 g/L before 14 weeks of pregnancy or a hemoglobin concentration below 110 g/L from 14 weeks of gestation to delivery19.

Data sources

Data for this study were extracted from the medical and test records of participants by the Information Department of West China Second Hospital of Sichuan University. The collected data included age, medical and family history, marital status, smoking and alcohol use, height, and admission weight. Information on pregnancy mode, exposure to estrogen-progestin, and any previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus was also retrieved. All data were de-identified to ensure participant privacy, and all participants reported no history of smoking or alcohol consumption.

Data statistics

This study considers serum ferritin levels as the exposure factor and GDM as the outcome factor. The potential confounding variables included in the analysis are age, gestational week at serum ferritin measurement, pre-pregnancy BMI, gravidity, parity, history of gestational diabetes, family history of diabetes, exposure to estrogen and progesterone in early pregnancy, and conception through assisted reproductive technology. Among these variables, serum ferritin levels, age, and gestational week at serum ferritin measurement are continuous variables, while pre-pregnancy BMI, gravidity, parity, history of gestational diabetes, family history of diabetes, exposure to estrogen and progesterone in early pregnancy, and conception through assisted reproductive technology are binary variables. All categorical variables are coded as 1 for positive and 0 for negative.

For continuous variables, differences were assessed after normality testing. If the data followed a normal distribution, they were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and the t-test was used to compare group differences. If data did not follow a normal distribution, they were expressed as median (interquartile range), and the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions, and differences between groups were compared using the chi-square test. To accurately characterize the association between serum ferritin levels and glucose metabolism characteristics, we performed Spearman correlation analysis between second-trimester serum ferritin levels (closest to the OGTT test) and fasting blood glucose, as well as 1-hour, and 2-hour post-glucose load blood glucose levels. We employed logistic regression, restricted cubic splines and propensity score matching to investigate the association between serum ferritin and GDM. Using a random forest model based on the Gini index and accuracy metrics, we conducted a ranking analysis of the importance of all confounding factors and serum ferritin features included in the association analysis.

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 and R software. Logistic regression models, restricted cubic spline models, propensity score matching models, and random forest models were implemented using the “glm,” “rms,” “MatchIt,” and “randomForest” packages in R version 4.3.1, respectively.

Ethical statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee, with all participants providing written informed consent.

Results

Comparison of baseline data

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the study included 12,434 normal pregnant individuals as the control group and 3599 GDM patients without additional comorbidities as the observation group. We analyzed baseline data for both groups, including age, gestational age, number of deliveries, gestational weight gain (GWG), pre-pregnancy BMI, history of GDM, family history of diabetes, conception via assisted reproductive technology, multiple pregnancies, and early pregnancy estrogen-progestin exposure. The results showed that all baseline variables were significantly higher in the GDM group compared to the control group, except for gestational weight gain, which was significantly lower in the GDM group (Table 1).

Comparison of ferritin differences and metabolic characterization

In the study population, the prevalence of iron deficiency was approximately 14.1% in the first trimester, 56.9% in the second, and 84.0% in the third. Ferritin levels were assessed between 23 and 27 weeks of gestation in 12,434 normal pregnant individuals and 3,599 individuals with GDM. Results indicated significantly higher ferritin levels in individuals with GDM (22.5 µg/L [IQR 19.33]) compared to normal pregnant individuals (20.6 µg/L [IQR 17.4]), with a p-value < 0.0001. In the late stages of pregnancy, ferritin levels were significantly higher in 3,317 GDM patients (18.2 µg/L [IQR 14.6]) compared to 11,636 normal pregnant individuals (17.3 µg/L [IQR 14.1]), P < 0.0001. Analysis of serum ferritin across pregnancy stages revealed a significant decrease with increasing gestational age in both normal controls (n = 7,663) and GDM subjects (n = 2,165) (Fig. 2).

Additionally, we compared anemia and iron deficiency rates between GDM patients and normal pregnant controls across all trimesters. The results showed that normal pregnant individuals had significantly higher rates of anemia in the second and third trimesters, iron deficiency in the second trimester, amniotic fluid staining, and premature rupture of membranes compared to GDM patients. Conversely, the GDM group had significantly higher rates of preterm labor and low birth weight at term compared to normal pregnant controls (Table 2).

Further analysis of iron deficiency during pregnancy in normal controls showed that iron deficiency did not affect the incidence of preterm labor. However, iron deficiency was associated with a higher proportion of low-birth-weight infants at term. Amniotic fluid staining and premature rupture of membranes were not significantly linked to iron deficiency (Table S1). Furthermore, in the analysis of anemia, subjects without anemia throughout pregnancy had lower incidences of preterm birth, and low birth weight infants compared to those who developed anemia during pregnancy. Anemia in early pregnancy alone does not appear to elevate the incidence of premature rupture of membranes (Table S2).

Association between ferritin concentration and glucose metabolism

The results revealed no significant association between serum ferritin concentration and fasting blood glucose. However, weak but significant positive correlations was observed between serum ferritin levels and blood glucose levels at 1-hour (Spearman’s r = 0.042, p < 0.05) and 2-hours post-glucose administration (Spearman’s r = 0.043, p < 0.05) (Figure S1).

Association between ferritin concentrations and GDM

Based on the observed statistical differences, we examined the association between serum ferritin levels and GDM using multivariable logistic regression and a restricted cubic spline model. The logistic regression revealed no significant association between ferritin levels in the first trimester and GDM. However, significant positive associations were observed between ferritin levels in the second and third trimesters and GDM. The adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and corresponding P-values were as follows: for the second trimester, AOR = 1.004 (95% CI: 1.002–1.005), P < 0.001; and for the third trimester, AOR = 1.002 (95% CI: 1.001–1.004), P < 0.001 (Fig. 3). Furthermore, trend analysis indicated that the risk of GDM increased with higher serum ferritin concentrations in the second and third trimesters compared to the lowest quartile (Q1) (Table 3).

Additionally, a restricted cubic spline model was constructed to explore potential nonlinear associations between serum ferritin levels and GDM, adjusting for the aforementioned factors. This analysis revealed no significant nonlinear association between ferritin in the first trimester and GDM (P for nonlinearity = 0.137), while significant nonlinear associations between ferritin in the second trimester (P for nonlinearity < 0.001) and the third trimester (P for nonlinearity = 0.036) and GDM (Fig. 4).

Propensity-matched score analysis of the association between serum ferritin levels and GDM in the second trimester. PE progesterone exposure, MP multiple pregnancy, HGDM history of GDM, HFDM family history of diabetes, GA gestational age of ferritin testing, BMIBP BMI before pregnancy, ART artificial reproductive technology.

Since ferritin testing in the second trimester closely aligns with GDM diagnosis, it provides a more accurate assessment of the association between serum ferritin and GDM during pregnancy. We further applied propensity score matching to minimize confounding and strengthen the analysis. The results showed optimal confounder balance when 1:1 matching was then performed using the nearest neighbor method with a caliper of 0.2, with none of the confounders demonstrating a statistically significant effect on GDM (Figure S2). Following optimal matching, we evaluated the association between serum ferritin and GDM using a logistic regression model. The analysis revealed that, following confounder adjustment, the OR for ferritin in the second trimester’s association with GDM was [AOR = 1.005 (95% CI: 1.003–1.007), P < 0.05] (Fig. 5). The OR and 95% CI remained consistent with those before matching, with no significant differences observed (Figure S3).

Random Forest algorithm for feature importance assessment of confounders. PE progesterone exposure, MP multiple pregnancy, HGDM history of GDM, HFDM family history of diabetes, GA gestational age of ferritin testing, BMIBP BMI before pregnancy, ART assisted reproductive technology derived pregnancy.

Factor importance ranking analysis

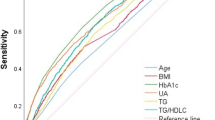

Given the ongoing clinical debate regarding the benefits and risks of iron supplementation, we sought to evaluate the relative importance of ferritin compared to other known risk factors for GDM. According to the Gini index, ferritin ranked third among all factors in terms of its effect on GDM. Conversely, when ranked by accuracy, ferritin was ranked ninth among all factors (Fig. 6).

Comparison of serum ferritin levels in normal pregnant individuals and gestational diabetes mellitus patients by trimester. A Comparison of serum ferritin concentrations in the first trimester between normal pregnant individuals and patients with GDM; B Comparison of mid-pregnancy serum ferritin concentrations in normal pregnant individuals and patients with GDM; C Comparison of late pregnancy serum ferritin concentrations in normal pregnant individuals and patients with GDM; D Variations in ferritin levels during gestation in normal pregnant individuals; E Variations in ferritin levels during gestation in patients with GDM. * for P < 0.05, ** for P < 0.01, *** for P < 0.001, **** for P < 0.0001, P < 0.05 was considered statistically positive.

Discussion

Existing studies have reported an association between elevated serum ferritin levels during pregnancy and an increased risk of GDM. This study utilized large-scale population data and employed logistic regression, restricted cubic spline analysis, and propensity score matching to evaluate the impact of serum ferritin levels throughout pregnancy on GDM. The study aims to further explore the correlation between serum ferritin and GDM, providing new empirical support for this association. Our study found that the association between serum ferritin levels and the risk of GDM was only present in the second and third trimesters. However, in the ranking of all GDM risk factors included in this study using the Random Forest algorithm, the importance of ferritin was lower than that of pre-pregnancy BMI and age. In other words, the contribution of serum ferritin levels to the risk of high GDM is weaker compared to risk factors such as BMI and age. Furthermore, analysis of the relationship between serum ferritin levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes in normal pregnancy individuals revealed that the incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes was significantly higher among those with low serum ferritin levels during pregnancy.

Our results align with previous study, which indicate that elevated serum ferritin levels during pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of GDM20. Trend tests and restricted cubic spline models confirmed a significant “dose-response” association for this effect. However, our findings revealed that the AOR for elevated serum ferritin levels associated with GDM risk (1.004, 95%CI:1.002–1.005 in gestational age between 23-27weeks; 1.002, 95%CI:1.001,1.004 in the third trimester) is relatively low. In the study by Yang et al., they reported that during the 16–18 weeks of pregnancy, as serum ferritin levels increased, OR and its 95% CI for the risk of GDM in the fourth percentile compared to the first percentile was 1.43 (1.09–1.89)21. The OR they reported was higher than our results, and the 95% CI was broader compared to our findings. Since the subjects included in the two studies had comparable mean ages and pre-pregnancy BMIs, and both used multifactorial logistic regression to estimate the relationship between serum ferritin and GDM risk, the reported discrepancies may be due to differences in sampling gestational age, the regions where the subjects were located, as well as variations in sample sizes. Furthermore, our study found no association between serum ferritin concentration in early pregnancy and GDM. In contrast, a retrospective study conducted in Shanghai reported a positive association between early pregnancy ferritin levels and insulin resistance as well as GDM22. In addition to differences in sample size and the studied population, variations in the confounding variables included in the models are also significant factors contributing to discrepancies in research reports. When adjusting for confounding variables, the study only considered age and pre-pregnancy BMI. However, in our research, we introduced multiple critical factors from a clinical perspective, such as age, early pregnancy hormone exposure, and multiple pregnancies, which enhances the credibility of our findings.

Previous studies have reported a positive correlation between serum ferritin levels and fasting glucose levels in patients with GDM, suggesting that elevated serum ferritin may be associated with severe pancreatic impairment14,23. This association appears to be supported by basic research. It has been suggested that an increase in the body’s iron reserve levels is associated with a rise in free elemental iron, which can elevate oxidative free radicals and, in turn, damage organ function through enhanced ferroptosis and oxidative stress10,24,25. Considering the varying glucose metabolism patterns with different levels of pancreatic injury, impaired fasting glucose often indicates more severe pancreatic dysfunction26. Our findings suggest that serum ferritin levels exhibit only a weak correlation with 1-hour and 2-hour blood glucose levels during the OGTT, which may imply that elevated serum ferritin is associated with only mild pancreatic dysfunction. The observed discrepancy in the correlation between ferritin and glucose levels during the OGTT may be attributed to two factors: (1) variations in sample sizes, where the previous study may have involved populations with more severe pancreatic damage, and (2) regional differences in iron levels, which could have resulted in higher ferritin levels in the previous study’s cohort27. These hypotheses warrant validation through multicenter studies with larger sample sizes.

To investigate the relationship between ferritin levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes, we stratified serum ferritin levels in healthy pregnant women and compared the incidences of four outcomes—low birth weight, premature rupture of membranes, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and preterm labor—across different ferritin levels. The results indicated that the proportion of low-birth-weight infants was significantly higher in the population with iron deficiency throughout pregnancy. However, for the other three adverse pregnancy outcomes, the proportions were comparable across the different categories. These findings suggest that iron deficiency has a significant effect on fetal growth and development during pregnancy, which is consistent with previous study28. Additionally, in the analysis of anemia, the incidence of preterm birth, meconium staining of amniotic fluid, premature rupture of membranes, and low birth weight was lower among participants who remained free of anemia throughout pregnancy compared to those who developed anemia during pregnancy. These findings are consistent with results from randomized clinical trial conducted in South India29. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2023 highlighted that both high and low serum hemoglobin levels could be linked to low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm labor30. These reports appear somewhat contradictory, which may be attributed to differences in population selection and varied statistical strategies. Our findings are based on an analysis of data from nearly 7000 normal pregnancies, examining the effects of iron deficiency and anemia on adverse pregnancy outcomes, which enhances the reliability of our results.

Iron deficiency is a major global public health concern, affecting over 28% of non-pregnant individuals worldwide31, and is especially severe among pregnant individuals32. In our study, we found that only 41.0% of participants had ferritin levels ≥ 70 µg/L in early pregnancy, and by late pregnancy, only 15.7% had serum ferritin levels of 30 µg/L or higher. This indicates that most pregnant women continue to experience iron deficiency in late pregnancy. To mitigate the heightened risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with iron deficiency, oral or intravenous iron supplementation is often recommended33. However, the therapeutic window for iron supplementation is narrow34, and recent studies have shown that elevated serum iron levels may cause tissue and organ damage35,36. This highlights the need for a more thorough evaluation of iron metabolism during pregnancy. Studies indicate that ferritin can serve as a marker of inflammation, as its levels may become abnormally elevated in response to an inflammatory environment37. During the first trimester, the body experiences a mild inflammatory state, which may explain our study’s null findings on the association between serum ferritin levels and GDM at this stage. Additionally, research has also shown that inflammation levels are higher in patients with gestational diabetes compared to normal pregnancies38. This heightened inflammatory response may help explain the observed linear association between ferritin levels and GDM in the second and third trimesters. To further clarify the relationship between ferritin and GDM, future studies should incorporate additional metrics, such as serum transferrin saturation and hepcidin, when evaluating ferritin levels39,40.

Our study found that elevated serum ferritin levels during the second and third trimesters were significantly associated with an increased risk of GDM, and this association remained significant after propensity score matching. Serum ferritin levels during mid-pregnancy were positively correlated with blood glucose levels in GDM screening. Additionally, low serum ferritin levels during pregnancy were associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight. Our study also has some limitations; unfortunately, it lacked data on iron supplementation, serum free iron ion levels, and serum C-reactive protein during the same period of ferritin testing, which somewhat impacted our results. However, due to the large number of cases included and more rigorous control of confounding factors, it remains one of the most scientifically sound studies on the association between serum ferritin and GDM.

Conclusion

Our findings underscore the need for additional studies to clarify the mechanisms underlying the association between serum ferritin levels and GDM. While this study highlights the relationship between elevated ferritin levels and GDM risk, we should remain cautious about the results, and further investigations are necessary to determine whether iron supplementation plays a role in this relationship.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

References

Benson, C. S. S. A. et al. The effect of iron deficiency and anaemia on women’s health. Anaesthesia 76 (Suppl 4), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15405 (2021).

M., R. T. Iron deficiency and Iron deficiency anemia: implications and impact in pregnancy, fetal development, and early childhood parameters. Nutrients 12 (2), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020447 (2020).

Braga, F. P. S., Frusciante, E., Borrillo, F., Chibireva, M. & Panteghini, M. Harmonization status of serum ferritin measurements and implications for use as marker of Iron-Related disorders. Clin. Chem. 68 (9), 1202–1210. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvac099 (2022).

Jäger, L. RY, Senn, O., BurgstallerJM, Rosemann, T. & Markun, S. Ferritin cutoffs and diagnosis of Iron deficiency in primary care. JAMA Netw. Open. 7 (8), e2425692. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25692 (2024).

Hansen, R. S. E., Holm, C. & Schroll, J. B. Iron supplements in pregnant women with normal iron status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 102 (9), 1147–1158. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14607 (2023).

A., M. Optimizing diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in women and girls of reproductive age: clinical opinion. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 162 (Suppl 2), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14949 (2023).

Gattermann, N. M. M., Kulozik, A. E., Metzgeroth, G. & Hastka, J. The evaluation of Iron deficiency and Iron overload. Dtsch. Arztebl Int. 118 (49), 847–856. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0290 (2021).

Hallberg, L. B. C., Lapidus, L., Lindstedt, G., Lundberg, P. A. & Hultén, L. Screening for iron deficiency: an analysis based on bone-marrow examinations and serum ferritin determinations in a population sample of women. Br. J. Haematol. 85 (4), 787–798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03225.x (1993).

Gao, H. J. Z. et al. Aberrant iron distribution via hepatocyte-stellate cell axis drives liver lipogenesis and fibrosis. Cell. Metab. 34 (8), 1201–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2022.07.006 (2022).

Harrison, A. V. L. F. & McClain, D. A. Iron and the pathophysiology of diabetes. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 85, 339–362. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-022522-102832 (2023).

Juan, J. Y. H. P. Prevention, and lifestyle intervention of gestational diabetes mellitus in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17 (24), 9517. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249517 (2020).

Sweeting, A. W. J., Murphy, H. R. & Ross, G. P. A clinical update on gestational diabetes mellitus. Endocr. Rev. 43 (5), 763–793. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnac003 (2022).

Cheng, Y. L. T. et al. The association of elevated serum ferritin concentration in early pregnancy with gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective observational study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 74 (5), 741–748. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0542-6 (2020).

Ji, J. W. P. et al. The associations of ferritin, serum lipid and plasma glucose levels across pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes mellitus and newborn birth weight. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23 (1), 478. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05806-z (2023).

Li, T. Z. J. & Li, P. Ferritin and iron supplements in gestational diabetes mellitus: less or more? Eur. J. Nutr. 63 (1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03250-5 (2024).

Durnwald, C. B. R. et al. Continuous glucose monitoring profiles in pregnancies with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 47 (8), 1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-2149/figshare.25630338 (2024).

Sweeting, A. H. W. et al. Epidemiology and management of gestational diabetes. Lancet 404 (10448), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00825-0 (2024).

Michael K. Georgieff. Iron deficiency in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. ;223(4):516–524 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.006

Smith, C. T. F., Branch, E., Chu, S. & Joseph, K. S. Maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with Anemia in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 134 (6), 1234–1244. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003557 (2019).

Sun, C. W. Q. et al. Association between the ferritin level and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Diabetes Investig. 11 (3), 707–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13170 (2020).

Yang, L. W. L. et al. Association between serum ferritin concentration and risk of adverse maternal and fetal pregnancy outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 15, 2867–2876. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S380408 (2022).

Zhang, Z. L. X. et al. Association of gestational hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes with serum ferritin levels in early pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1067655. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1067655 (2023).

Sharifi, F. Z. A., Feizi, A., Mousavinasab, N., Anjomshoaa, A. & Mokhtari, P. Serum ferritin concentration in gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of subsequent development of early postpartum diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 3 https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSOTT.S15049 (2010).

Nakamura, T. N. I. & Ichijo, H. Iron homeostasis and iron-regulated ROS in cell death, senescence and human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1863, 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.06.010 (2019).

Feng, Y. F. Q., Lv, Y., Song, X., Qu, H. & Chen, Y. The relationship between iron metabolism, stress hormones, and insulin resistance in gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Diabetes. 10 (1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-020-0122-9 (2020).

Nagy, A. J. M. et al. Glucose levels show independent and dose-dependent association with worsening acute pancreatitis outcomes: Post-hoc analysis of a prospective, international cohort of 2250 acute pancreatitis cases. Pancreatology 21 (7), 1237–1246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2021.06.003 (2021).

Karregat, J. H. M. E. S., Castrén, J., Arvas, M. & van den Hurk, K. Iron status in Dutch and Finnish blood donor and general populations: A cross-cohort comparison study. Vox Sang. 119 (7), 664–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/vox.13639 (2024).

Ying, Y. P. P. et al. Tebuconazole exposure disrupts placental function and causes fetal low birth weight in rats. Chemosphere 264 (Pt 2), 128432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128432 (2021).

Finkelstein, J. L. K. A., Bose, B., Thomas, T., Srinivasan, K. & Duggan, C. Anaemia and iron deficiency in pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes in Southern India. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 74 (1), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-019-0464-3 (2020).

Young, M. F. O. B. et al. Maternal low and high hemoglobin concentrations and associations with adverse maternal and infant health outcomes: an updated global systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23 (1), 264. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05489-6 (2023).

Ning, S. Z. M. Management of iron deficiency. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2019 (1), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1182/hematology.2019000034 (2019).

Benson, A. E. S. J. et al. The incidence, complications, and treatment of iron deficiency in pregnancy. Eur. J. Haematol. 109 (6), 633–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13870 (2022).

Cantor, A. G. B. C., Dana, T., Blazina, I. & McDonagh, M. Routine iron supplementation and screening for iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive services task force. Ann. Intern. Med. 162 (8), 566–576. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2932 (2015).

Georgieff, M. K. K. N. & Cusick, S. E. The benefits and risks of Iron supplementation in pregnancy and childhood. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 39, 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-082018-124213 (2019).

Zhang, Y. L. Y. & Jin, L. Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in physiological and pathological pregnancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (16), 9395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23169395 (2022).

Rak, K. Ł. K., Styczyńska, M., Bobak, Ł. & Bronkowska, M. Oxidative stress at birth is associated with the concentration of Iron and copper in maternal serum. Nutrients 13 (5), 1491. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051491 (2021).

Hortová-Kohoutková, M. et al. Hepcidin and ferritin levels as markers of immune cell activation during septic shock, severe COVID-19 and sterile inflammation. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1110540 (2023).

Pinto, Y. F. S. et al. Gestational diabetes is driven by microbiota-induced inflammation months before diagnosis. Gut 72 (5), 918–928. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328406 (2023).

Pasricha, S. R. T. D. J., Muckenthaler, M. U. & Swinkels, D. W. Iron deficiency. Lancet 397 (10270), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32594-0 (2021).

Zhang, Y. M. Y. et al. Correlation between the systemic immune-inflammation indicator (SII) and serum ferritin in US adults: a cross-sectional study based on NHANES 2015–2018. Ann. Med. 55 (2), 2275148. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2275148 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to all study participants who agreed to participate in this study.

Funding

The present paper is funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Fund (granted NO.82301924) and Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (granted NO.2022YFS0043).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H. and X.P.; methodology, Y.H., X.P. and Y.X.; software, Y.X.; validation, Y.X., Q.C. and S.D.; resources, Y.X. and S.D.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, Y.H., X.P. and Y.X.; project administration, Y.X.; funding acquisition, D.S. and Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University (2023 Medical scientific research for ethical approval No.(163)). All of the participants provided written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Y., Dai, S., Chen, Q. et al. Serum ferritin levels and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 7525 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91456-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91456-4