Abstract

Surgical castration of males is carried out on a large scale in the US swine industry and the pain resulting from this procedure can be assessed using the Unesp-Botucatu pig composite acute pain scale (UPAPS). We aim to propose a short version of UPAPS based on the behaviors best-ranked by a random forest algorithm. We used behavioral observations from databases of surgically castrated pre-weaned and weaned pigs. We trained a random forest algorithm using the pain-free (pre-castration) and painful (post-castration) conditions as target variable and the 17 UPAPS pain-altered behaviors as feature variables. We ranked the behaviors by their importance in diagnosing pain. The algorithm was refined using a backward step-up procedure, establishing the Short UPAPS. The predictive capacity of the original and short version of the UPAPS was estimated by the area under the curve (AUC). In refinement, the algorithm with the five best-ranked behaviors had the lowest complexity and predictive capacity equivalent to the algorithm with all behaviors. The AUC of Short UPAPS (89.62%) was statistically equivalent (p = 0.6828) to that of UPAPS (90.58%). In conclusion, the proposed Short UPAPS might facilitate the implementation of a standard operating procedure to monitor and diagnose acute pain post-castration in large-scale systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a forecast of an increase in the world’s human population1 which assumes an increase in demand for food. One-third of the protein for the human diet is provided by livestock, and pork is the second most consumed meat in the world2,3. In most of the swine industry, male piglets are castrated to avoid boar taint and tastes in the pork and to minimize undesirable aggressive and sexual behaviors4. Although alternative options exist to eliminate these issues without surgical procedures (e.g. immunological castration), these alternatives are not routinely performed yet in the first (China) and third (United States) largest swine producers in the world, and most of the piglets consistently are submitted to surgical castration without any anesthesia or analgesia5,6,7,8,9,10. In this context, meeting the demand for pork considering consumers’ current concern about pigs’ quality of life is a global animal welfare issue3,5,11,12,13 and requires practical methods to identify animals experiencing pain on-field.

Pain is defined as an “unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”14 and directly impacts an animal’s quality of life15. In addition to the ethical reason for pain relief, studies indicate that acute pain after surgical castration reduces weight gain in piglets, reinforcing the need to recognize and manage pain appropriately on farms16,17,18,19. Pain diagnosis in non-verbal mammals is considered a challenge, and in the case of piglet castration, the behavioral response has been used for this purpose20. There is no pain-altered behavior that is considered a pathognomonic sign of pain21,22. Therefore, pain scales usually combine behavioral categories related to pain or discomfort (e.g.: attention to the affected area, tail wagging, and lowering the head) and maintenance (e.g.: interaction with the environment and other animals, activity, and appetite) that can change when animals experience pain23,24,25,26.

In 2020, a species-specific behavioral scale was developed to assess acute pain in swine before and after surgical castration. The Unesp-Botucatu Pig Composite Acute Pain Scale (UPAPS) was validated for both weaned23 and pre-weaned piglets24 and underwent a psychometric validation process based on several statistical steps27,28. After completing the validation, 17 pain-altered behaviors categorized within five behavioral items were identified, defined, and used to assess pain via individual continuous observation for short intervals (4-min)23,24. UPAPS has been used not only as a diagnostic tool for acute pain but has also served to quantify the efficacy of analgesic intervention strategies29,30. However, pain assessment can often be time-consuming and require additional labor to assess pain during the surgical castration routines. Surgical castration is conducted on a large-scale system in commercial farms15,31,32 and it can be challenging to implement pain monitoring and diagnosing with limited time and labor to assess acute pain across all animals. Therefore, identifying a more concise method to assess pain in pigs is needed intervention analgesia decision making for mitigating acute pain.

Recently, research from our lab utilized principal component analysis, canonical discriminant analysis, and logistic regression to rank each of the 17 UPAPS pain-altered behaviors and improve the pain diagnosis33,34. For sheep, we used a random forest algorithm to rank pain-altered behaviors35. It is a machine learning technique, in which the algorithm can capture a pattern in the data after training using several decision trees36,37,38. One of the advantages of this technique is it is less likely to promote overfitting and improve prediction accuracy36,37,38,39. Thus, the random forest can contribute to identifying important behaviors that drive pain assessment outcomes in castrated pigs. The refinement of pain scales to establish an concise version that still maintain accuracy, might facilitate a more realistic pain monitoring protocol for large-scale systems. This short pain scale version might enable on-farm delivery of pain mitigation and improve pig’s welfare. However, to the best of our knowledge, pain-altered behaviors in pigs have not been ranked by random forest yet to propose a short version of the UPAPS. In addition, from a pain study perspective in general, the use of machine learning techniques is a novel approach to refine and to establish short pain scale versions across several species.

Therefore, we aimed to propose a short version of UPAPS based on the pain-altered behaviors best-ranked by the random forest algorithm using pigs before and after surgical castration.

Results

Reliability

Inter-observer reliability of the UPAPS total sum was considered “good” to “very good” according to the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (Table 1). Specifically for the weaned pig database, the ICC ranged from 0.85 to 0.92, while the pre-weaned pig database was 0.98.

Training random forest

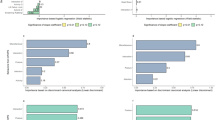

‘Head down’, ‘Sits with difficulty’, ‘Wags tail’, ‘Interaction 2’ (occasionally moves away from the other animals, but accepts approaches; shows little interest in the surroundings), and ‘Activity 1’ (moves with less frequency) respectively, were the five pain-altered behaviors best-ranked by the random forest algorithm to classify pigs in painful condition and those in pain-free condition (Fig. 1).

Testing random forest

The random forest algorithm had an AUC of 91.38%, which was statistically equivalent (p = 0.8545) to the AUC of UPAPS (90.58%) (Table 2).

Refining random forest

The algorithms with the four (AUC = 87.04%; p = 0.0360), three (AUC = 84.48%; p = 0.0150), and two (AUC = 79.00%; p < 0.0001) best-ranked pain-altered behaviors had lower AUCs than the algorithm containing all pain-altered behaviors (AUC = 91.38%) (Table S1 and Fig. 2). The other algorithms had AUC ranging from 89.12 to 91.44% and statistically equivalent (p < 0.05) to the algorithm with all pain-altered behaviors, and among them, the algorithm with the five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors had the lowest complexity (fewer pain-altered behaviors).

Refinement of the random forest algorithm based on the importance ranking of UPAPS pain-altered behaviors (AUC indicates area under the curve; y-axis indicates the number of pain-altered behaviors according to the ranking by the algorithm; *indicates a significant difference in AUC in relation to the algorithm with all pain-altered behaviors; the dashed line indicates the AUC of the algorithm with all pain-altered behaviors; the black rectangle indicates the algorithm with the smallest number of pain-altered behaviors (lowest complexity) and having the AUC statistically equivalent to that of the algorithm with all pain-altered behaviors).

Short pain scale

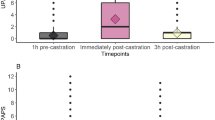

The AUC of UPAPS (90.58%) was statistically equivalent (p = 0.4940) to its short version (89.62%) (Table 3). Short UPAPS total sum ranged from 0 to 5 and had an optimal cut-off point of 2 based on the upper 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

Pain monitoring in the swine industry is a global animal welfare challenge41 and the Unesp-Botucatu Pig Composite Acute Pain Scale (UPAPS) is the leading tool for assessing and diagnosing pain in pigs23,24. Our team previously ranked the importance of each UPAPS pain-altered behavior based on principal component analysis, canonical discriminant analysis, and logistic regression to optimize application33,34, however, no work to date has ranked these pain-altered behaviors using machine learning techniques to develop a short version of this pain scale. Therefore, we aimed to propose a short version of UPAPS based on the pain-altered behaviors best-ranked by the random forest algorithm using pigs before and after surgical castration.

Acute pain in non-human mammals has been widely monitored by the behavioral response due to its practicality, non-invasiveness, non-intrusiveness, and low cost32. Despite the advantages, manual annotation of the behavior is considered an assessment with a certain degree of subjectivity, and it is essential to use more than one observer and estimate the level of reliability between them42. In the current study, we used five experienced observers in swine pain assessment, who had satisfactory inter-observer reliability for the UPAPS total sum. Based on this finding, we assumed behavioral assessments were reliable in the study.

When training the random forest algorithm, the importance of UPAPS pain-altered behaviors was heterogeneous, making it possible to rank this behavioral set. The five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors (‘Head down’, ‘Sits with difficulty’, ‘Wags tail’, ‘Interaction 2: occasionally moves away from the other animals but accepts approaches; shows little interest in the surroundings’, and ‘Activity 1: moves with less frequency’) are similar to behaviors that had already been well-documented. The literature suggests that each of these five behaviors is identified as consistent indicators of acute pain in swine. Following castration, piglets decreased their locomotion behaviors16,17,43,44, interaction with the environment and conspecifics5,43,45. Furthermore, it has been reported that piglets post-castration have increased difficulty in getting up and or lying down5,43,45,46, increased tail movements17,43,44,46,47 and they remain with their head lowered (prostrate)45,46,47.

The first (‘Head down’), fourth (‘Interaction 2: occasionally moves away from the other animals, but accepts approaches; shows little interest in the surroundings’) and fifth (‘Activity 1: moves with less frequency’) best-ranked pain-altered behaviors can be understood as behaviors related to both a reduction of the animal’s movement and its interaction with the environment and other individuals, while the second in the ranking (‘Sits with difficulty’) can be interpreted as a reduction in movement associated with the protection of the operated area. A plausible explanation for such behaviors is the evolutionary purpose of conserving energy and protecting the injured area to heal the inflamed tissue, avoiding activities that are not essential for survival48,49,50,51,52,53,54. Another justification may be the isolation that social mammals express in situations of imminent threat55. In addition to the reduction in movement and socialization, the increase in “Wags tail” was the third best-ranked pain-altered behavior and can be partially explained as a sign of discomfort due to an increase in neuromuscular responses in the surgical area. In humans56,57, cats58, and rats58, pain can result in greater activation of the sympathetic nervous system, increasing muscle activity. In summary, the five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors indicate reduced movement and socialization, as well as increased protection of the affected area and discomfort in response to the change in homeostasis during acute pain49,59.

The set of five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors in the present study are associated with pain, discomfort and or maintenance behaviors, as previously found in pigs33,34, horses60, and cattle61. In contrast, the five most important behaviors for pain diagnosis in sheep were exclusively from the maintenance category35, reinforcing the relevance of ranking behaviors altered by pain on each species-specific scale. Specifically for pigs, the Head down, Wags tail and Interaction 2 (‘occasionally moves away from the other animals, but accepts approaches; shows little interest in the surroundings’) were among the five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors in our current and previous works33,34. However, the other two of five pain-altered behaviors were different across studies and might be explained by (i) the database used, (ii) the type of algorithms, and (iii) the type of target and feature variables used as input to the algorithm for each study. Further studies should explore new study population of pigs and observers to cover larger individual variability.

Testing the random forest algorithm, the predictive ability was ‘good’27 and statistically equivalent to the predictive ability of UPAPS, allowing the use of the ranking. Similar findings were found using other techniques to rank pain-altered behaviors in pigs34 but different in previous studies on sheep35 and horses60 where the predictive capacity of the algorithms used was superior to the predictive ability of the original scales. For pigs, it is possible that the UPAPS in its original version already has an adequate balance between the behavioral items23,24, which partially explains why the statistical weighting does not have a superior predictive capacity, even applying different techniques in the present and previous research34.

The refinement of the random forest algorithm was conducted with a backward step-up procedure unprecedentedly designed to select a relevant set of pain-altered behaviors in non-human mammals. In our study, the algorithm with the five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors had the lowest complexity (smallest number of pain-altered behaviors) without losing the predictive capacity, considering the algorithm with all pain-altered behaviors, which follows the principle of parsimony62. Differently, another study applied principal component and canonical discriminant analyses but did not achieve a refinement of the piglet grimace scale63.

One novelty of the present study was the Short UPAPS proposal based on the refinement by the random forest algorithm. The Short UPAPS and the original did not significantly differ in discriminatory ability. The optimal cut-off point above 2 on the Short UPAPS total sum determined that the occurrence of only two of the five best-ranked pain-altered behaviors indicates a painful condition. It is worth mentioning that Short UPAPS was effective in identifying acute pain, considering exclusively surgical castration of weaned and pre-weaned pigs.

One limitation of the study was the sample imbalance between weaned and pre-weaned pigs when we merged the databases. Despite this, the algorithm’s performance metrics were satisfactory and future studies could expand the sample size. One of our databases23 was composed of weaned pigs and it was collected during the first study developing the UPAPS because it is easier to recognize pain-altered behavior in older pigs than in young ones, but future studies should consider enlarging the sample size of pre-weaned pigs because this is the common age to castrate piglets. For both databases, although the observers were masked to the timepoints, in some cases surgical wounds could be recognizable, which makes the analysis partially blind. Another limitation was the step-up backward procedure used to refine the UPAPS because this method does not consider all the multiple combinations between the 17 pain-altered behaviors. However, the procedure adopted resulted in a short version of the pain scale with a satisfactory predictive capacity. Exhaustive methods to explore the all multiple combinations of feature variables in machine learning algorithms require a huge computational capacity that might be explored in the future. Lastly, future research should include a sham group to further refine the pain scale in being able to discriminate stress due to handling plus pain than only stress, avoiding false positive diagnoses64. However, the sham group in a previous study had maximum UPAPS total sum of 3, below the optimal cutoff point (UPAPS total sum ≥ 4) indicating positive pain diagnosis, and suggesting that stress effect did not induced false positive diagnoses29.

One of the practical implications of our findings was the reduction from 17 to five pain-altered behaviors between the original scale and its short version. Although the original UPAPS can be used in real-time or video-recorded equivalently65, farmers and veterinarians agree on the difficulty of recognizing pain in pigs in general66,67,68,69. Therefore, Short UPAPS has the potential to facilitate the training of caretakers on swine farms and implement a standard operating procedure to monitor acute pain in routine surgical castration for large-scale systems, promoting pigs’ welfare. It is worth noting that a transition is taking place on pig farms towards the adoption of immunological castration instead of surgical castration70,71, however, surgical castration is still commonly used worldwide and it is a welfare issue requiring attention6,7,8. Additionally, the methodological approach used to refine the algorithm and propose a short version of the UPAPS can be easily translated to pain scales in other species.

Our study represents the first step to optimize the pig pain assessment on farm, and subsequent steps are necessary before implement the proposed short version of the UPAPS as a pain monitoring system on farm. In the future, the short version of the UPAPS proposed in this research should be validated based on psychometric properties following the guidelines of the consensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement instruments (COSMIN) guidelines28 as done for the original version23,24. The COSMIN guidelines aims to improve the selection of outcome measurement instruments both in research and in clinical practice by developing methodology and practical tools for selecting the most suitable outcome measurement instrument28. This psychometric validation should be performed using a new population of pigs. Furthermore, it could be investigated whether the use of Short UPAPS can be applied in life assessment by a presential observer with the same validation than video-record assessments, reduces observer’s fatigue, assessment time-consumption, and enables to assess multiple pigs simultaneously. Lastly, the accuracy of the proposed short version of the UPAPS should be tested under different pain-mitigation strategies because the legislation across countries worldwide varies. For example, the guidelines of the second (Europe Union) and fourth (Brazil) largest swine producers in the world encourages farmers to conduct surgical castration under an anesthesia and analgesia protocol72,73.

In conclusion, we identified a ranking of the importance of UPAPS pain-altered behaviors using a random forest algorithm and found that the predictive capacity of the algorithm was equivalent to UPAPS. Furthermore, we determined a short version of the UPAPS based on the five pain-altered behaviors best-ranked by the algorithm that had a discriminatory ability equivalent to the original version of the UPAPS. Finally, the proposed Short UPAPS might facilitate implementing acute pain monitoring in surgical castration routines in large-scale systems. Future studies are needed to validate the proposed Short UPAPS based on psychometric properties following the COSMIN guidelines.

Materials and methods

The current study was conducted with a database originating from two previous publications with weaned23 and pre-weaned pigs24, including new statistical analyses. The experiment procedures generating the weaned pig database were approved by the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals in Research (protocol number 102/2014) of the School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science of the São Paulo State University (Unesp), Botucatu, Brazil, and followed federal legislation of the Brazilian National Council for the Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA)23. The study generating the pre-weaned pig database was approved under protocol number 19–796 by the North Carolina State University Animal Care and Use Committee24. Both previous studies followed the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research74. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. We understand that database reuse contributes to two of the four R’s of animal experimentation (reduction and responsibility)75,76.

Database

Weaned pig database

The weaned pig database consisted of pain-altered behavioral recordings from 45 male pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus), of the Landrace, Large White, Duroc and Hampshire breeds, aged 38 ± 3 days and weighing 11.06 ± 2.28 kg and housed in iron pens (2.40 × 1.50 × 1.50 m of length x width x height) located side by side separated by bars in groups of five pigs. Before surgery, pigs underwent bilateral local anesthesia with 0.5 mL of 1% lidocaine without vasoconstrictor (Xylestesin®, Cristália, Itapira, São Paulo, Brazil) injected subcutaneously into each incision line, parallel to the diaphysis of the scrotum, followed by 1 mL intratesticularly injected into each testicle, and surgery was performed after five minutes. The pigs were filmed (DCR-SR68, SONY®, China) for 4 min at two perioperative timepoints: 24 to 16 h before surgery (pain-free condition) and 3.5 to 4 h after surgery (painful condition). Three observers conducted behavioral pain assessment on all videos. Two observers (Observer 1 and 2) were male professors with over 30 years of experience and one observer (Observer 3) was a female researcher with five years of experience in anesthesia and pain assessment in farm animals. In the original study, all observers assessed all videos (phase 1) and repeated all video assessments after an interval (phase 2) due to psychometric validation steps23. However, we used only the first phase of the assessment to merge the two databases, since in the pre-weaned pig database (described below) was performed only one assessment phase. Full details of management, procedures, protocols, and housing can be found in the previous publication23.

Pre-weaned pig database

The pre-weaned pig database24 consisted of pain-altered behavioral recordings from 14 Yorkshire-Landrace x Duroc piglets, five days old and weighing 1.62 ± 0.23 kg, housed with sows in individual farrowing crates (0.8 × 2.3 m of length x width) in fully slatted floors in a farrowing room with controlled environment conditions. No general or local anesthesia was administered due to standard management practices in the United States and the procedure followed the standard operating procedure approved by the treating veterinarian. The castration procedure occurred independently of research on all male animals on site. All animals enrolled in the pre-weaned pig dataset received intramuscular flunixin meglumine (2.2 mg/kg IM flunixin meglumine; Merck Animal Health, Millsboro, DE, USA) one hour after surgery. The pigs were filmed (AMCREST IP3M-943B; Houston, TX, US; one camera per crate) for 4 min at two perioperative time points: 24 h before surgery (pain-free condition) and 15 min after surgery (painful condition) only when pigs were awake. Two observers (Observer 4 and Observer 5) conducted behavioral pain assessment on all videos once. The observers were female researchers with more than two years of experience assessing pain in farm animals. Full details of management, procedures, protocols, and housing are described in the previous study24.

Behavioral pain scale

Observers were instructed to first watch each video and then score the behavioral indicators of the Unesp-Botucatu pig composite pain scale (UPAPS) described in the (Table 4)23,24. The observers were masked to the timepoint analyzed assessing the videos in a randomized order (blind analysis). The UPAPS was developed and published in an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source were credited.

In UPAPS, six behavioral items are assessed relating to posture, interaction and interest in the surroundings, activity, appetite (exclusive for weaned pigs), attention to the affected area, and miscellaneous behaviors23,24. These behavioral items are classified according to four descriptive levels (‘0’, ‘1’, ‘2’, and ‘3’). Level ‘0’ indicates normal behaviors not associated with pain, while levels ‘1’, ‘2’ and ‘3’ indicate pain-altered behaviors proportional to the intensity of pain23,24. Tutorial videos for each UPAPS behaviors can be seen on the Animal Pain website (https://animalpain.org/en/porcos-dor-en/) and in the Vetpain app (https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.vetpain.app for Android or https://apps.apple.com/ca/app/vetpain/id6462712970 for IOS).

Originally, the UPAPS for weaned pigs contained an item related to feeding (Appetite), however, in the validation of the UPAPS for pre-weaned pigs, an analogous item (Nursing) was considered sub-optimal and it was not included in the final version for pre-weaned pigs scale24. Therefore, in the current study, we disregarded both food-related items (Appetite and Nursing item) to combine the two databases. The total sum of the five behavioral items ranged from 0 to 15 and represented the intensity of pain according to UPAPS.

Statistical description

Statistical analysis was conducted in the R programming language, in the RStudio integrated development environment77 (Version 4.3.0; RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA). The functions and packages used were described as ‘package::function’ format corresponding to the programming language used. For all tests, a significance level of 5% (p < 0.05) was considered. Palette colors distinguishable by people with common forms of color blindness were used to construct the figures (ggplot2::scale_colour_viridis_d).

Sample size computation

The sample size was estimated using 80% power, with 0.05 as the significance level, and 0.90 of the area under the curve according to a receiver operating characteristic curve test (pROC::power.roc.test). Based on these premises, the minimum sample size estimated was six cases (painful conditions) and six controls (pain-free conditions).

Reliability

The inter-observer reliability of the UPAPS total sum was assessed by the degree of agreement between pairs of observers separately for each database. The Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. The values obtained were interpreted using the Altman classification: 0.81–1.0 very good; 0.61–0.8 good; 0.41–0.6 moderate; 0.21–0.4 fair; and < 0.2 poor40. Reliability was conducted using 100% of all databases.

Train–test split

The database was separated into a division for training (training base) and another for testing (testing base). The training base contained 70% of the pigs (31 weaned and 10 pre-weaned) selected randomly, while the testing base had 30% of the remaining pigs (14 weaned and four pre-weaned). Both training and testing bases remained with five observers, two perioperative timepoints, and two age groups, exclusively changing the number of pigs and, consequently, the number of observations (226 and 100, respectively, for the training and testing base).

Random forest

Random Forest is considered an type of ensemble bootstrap aggregation machine learning technique for classification and regression36,38,39. In Random Forest, several (uncorrelated) decision trees are built with random samples from the training database, and the most common result among all trees in the forest is used to make classification predictions on the testing base38,39. One of the advantages of this technique is to reduce overfitting and improve prediction accuracy36,38,39.

Training random forest

The random forest algorithm (caret::trainControl and caret::train) was built with a training base using the condition pain-free (before castration) or painful (after castration) as target variable. The pain-altered behavioral from the five UPAPS behavioral items (levels ‘1’, ‘2’, and ‘3’) were converted into 17 dummy variables (0 = absence and 1 = presence of each level of each item) and used as feature variables in the algorithm (fastDummies::dummy_columns), as already proposed by our team33,34,35,60. In this way, each dummy variable represented one UPAPS pain-altered behavior. All trees were based on the Gini coefficient. The list of UPAPS items names andtheir respective dummy variables (pain-altered behaviors) used in the algorithm can be seen in the Table S2.

The optimization (tuning) of the algorithm was conducted adjusting the random forest hyperparameters and cross-validation parameters by using the grid search technique, testing (i) two to 17 feature variables in each decision tree, (ii) 501, 1001 and 2001 decision trees in the forest, (iii) two to 10 folds in k-fold technique and (iv) two to 10 repetitions. Based on the grid search technique, 3888 algorithms were evaluated with multiple combinations of random forest hyperparameters and cross-validation parameters, and their accuracy was on average 92.07 ± 0.66%. The random forest algorithm with the highest accuracy (94.26%) contained two feature variables in each decision tree, 501 trees in the forest, four-folds, and nine repetitions, which was assumed as the optimal complexity algorithm to be used in the study.

Finally, the ranking of the importance of each pain-altered behavior (caret::varImp) according to the classification of the selected algorithm was presented in a bar plot (ggplot2::ggplot).

Testing random forest

To evaluate the predictive capacity of the algorithm, the area under the curve (AUC) and its 95% confidence interval obtained with 1001 bootstrap repetitions were estimated (pROC::roc; pROC::ci.auc; and pROC::ci .coords). The AUC is obtained by the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) based on a predictor variable that represents a reference parameter for the phenomenon and a predictive variable that is the parameter to be tested78. AUC above 90 is considered ‘good’ and above 95 is ‘excellent’. The ROC curve for each algorithm was constructed using the condition (painful and pain-free) as a predictive variable and the UPAPS total sum or the probability of each pig needing analgesia based each algorithm as a predictive variable (pROC::ROC). To obtain the AUC, it is necessary to establish an optimal cut-off point for each predictive variable, which was based on the Youden index (YI). The YI is estimated based on the sum of specificity and sensitivity subtracted from 1, calculated for each value of the predictive variable. The YI represents the maximum specificity and sensitivity concomitantly, attributing similar importance of specificity and sensitivity to the optimal cut-off point. The algorithms’ AUC were compared with UPAPS’s AUC by the DeLong test (pROC::roc.test).

Refining random forest

We use the ranking established by random forest training to reduce the number of pain-altered behaviors in the algorithm based on a step-up backward procedure. In this way, an algorithm was built using the training base, with exclusively the 16 best-ranked pain-altered behaviors, and this procedure was repeated sequentially until an algorithm was built with only the two best-ranked pain-altered behaviors. Using the testing base, the AUC of all algorithms with different numbers of pain-altered behaviors was compared with the AUC of the algorithm containing all behaviors using the DeLong test. The algorithm with the smallest number of pain-altered behaviors (lowest complexity) having an AUC statistically equivalent to or greater than the algorithm with all pain-altered behaviors was understood as the best refinement.

Short pain scale

The pain-altered behaviors contained in the algorithm with the best refinement were added together to make the Short UPAPS total sum, with each pain-altered behavior computed value ‘1’ in the total sum regardless of its classification on the original scale. An optimal cut-off point was established for Short UPAPS based on the high 95% confidence interval of the YI, as described in the previous session. Finally, the AUC of the Short UPAPS was compared with the AUC of the UPAPS using the DeLong test. These steps were done with the testing base.

Data availability

The R script (Appendix file S1) and databases (Appendix file S2, S3, and S4) used for the current study are available in supplementary information files without restrictions. The R code was commented using # specifying each step following the heading sequence described at the statistical description section. In addition, the code is available in https://github.com/PeterTrindade/Proposing-a-short-version-of-the-Unesp-Botucatu-Pig-Acute-Pain-Scale.git.

References

Fao, F. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations. Rome http://faostat.fao.org2, (2018).

Suryawanshi, K. R. et al. Impact of wild prey availability on livestock predation by snow leopards. R Soc. Open Sci. 4, (2017).

Collins, L. M., Smith, L. M. & Review Smart agri-systems for the pig industry. Animal 16, (2022).

Bonneau Weiler. Pros and cons of alternatives to piglet castration: welfare, Boar taint, and other meat quality traits. Animals 9, 884 (2019).

Sutherland, M. A. Welfare implications of invasive piglet husbandry procedures, methods of alleviation and alternatives: a review. N. Z. Vet. J. 63, 52–57 (2015).

Von Borell, E. et al. Animal welfare implications of surgical castration and its alternatives in pigs. Animal 3 (11), 1488–1496 (2009).

Burkemper, M. C., Pairis-Garcia, M. D., Moraes, L. E., Park, R. M. & Moeller, S. J. Effects of oral meloxicam and topical Lidocaine on pain associated behaviors of piglets undergoing surgical castration. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 23, 209–218 (2020).

Tomasevic, I. & Bahelka, I. Čandek-Potokar. Attitudes and Beliefs of Eastern European Consumers Towards Piglet Castration and Meat from Castrated Pigs (Elsevier, 2020).

Lin-Schilstra, L. & Ingenbleek, P. T. A scenario analysis for implementing immunocastration as a single solution for piglet castration. Animals 12 (13), 1625 (2022).

H.R.8994–118th Congress: Pigs and Public Health Act. julho 11). https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/8994 (2024).

Delsart, M., Pol, F., Dufour, B., Rose, N. & Fablet, C. Pig farming in alternative systems: strengths and challenges in terms of animal welfare, biosecurity, animal health and pork safety. Agriculture 10 (7), 261 (2020).

Fonseca, R. P. & Sanchez-Sabate, R. Consumers’ attitudes towards animal suffering: A systematic review on awareness, willingness and dietary change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (23), 16372 (2022).

Hötzel, M. J., Yunes, M. C., Vandresen, B., Albernaz-Gonçalves, R. & Woodroffe, R. E. On the road to end pig pain: knowledge and attitudes of Brazilian citizens regarding castration. Animals 10 (10), 1826.12 (2020).

Raja, S. N. et al. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 161, 1976–1982 (2020).

Rault, J. L., Lay, D. C. & Marchant, J. N. Castration induced pain in pigs and other livestock. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 135, 214–225 (2011).

McGlone, J. J., Nicholson, R. I., Hellman, J. M. & Herzog, D. N. The development of pain in young pigs associated with castration and attempts to prevent castration-induced behavioral changes. J. Anim. Sci. 71, 1441–1446 (1993).

Torrey, S., Devillers, N., Lessard, M., Farmer, C. & Widowski, T. Effect of age on the behavioral and physiological responses of piglets to tail Docking and ear Notching. J. Anim. Sci. 87, 1778–1786 (2009).

Telles, F. G., Luna, S. P. L., Teixeira, G. & Berto, D. A. Long-term weight gain and economic impact in pigs castrated under local anaesthesia. Vet. Anim. Sci. 1–2, 36–39 (2016).

Pérez-Ciria, L., Miana-Mena, F. J., Álvarez-Rodríguez, J. & Latorre, M. A. Effect of castration type and diet on growth performance, serum sex hormones and metabolites, and carcass quality of heavy male pigs. Animals 12 (8), 1004 (2022).

Gigliuto, C. et al. Pain assessment in animal models: do we need further studies? J. Pain Res. 7, 227–236 (2014).

Molony, V., Kent, J. E. & Robertson, I. S. Behavioural responses of lambs of three ages in the first three hours after three methods of castration and tail Docking. Res. Vet. Sci. 55 (2), 236–245 (1993).

Small, A. H., Jongman, E. C., Niemeyer, D., Lee, C. & Colditz, I. G. Efficacy of precisely injected single local bolus of Lignocaine for alleviation of behavioral responses to pain during tail docking and castration of lambs with rubber. 133, 210–218 (2020).

Luna, S. P. L. et al. Validation of the UNESP-Botucatu pig composite acute pain scale (UPAPS). PLoS One 15, (2020).

Robles, I. et al. Validation of the Unesp-Botucatu pig composite acute pain scale (UPAPS) in piglets undergoing castration. PLoS One 18, (2023).

Ison, S. H., Clutton, E., Di Giminiani, R. & Rutherford, K. P.M. D. A review of pain assessment in pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. 3, (2016).

Steagall, P. V., Bustamante, H., Johnson, C. B. & Turner, P. V. Pain management in farm animals: focus on cattle sheep and pigs. Anim. (Basel) 11, 1483 (2021).

Streiner, D., Norman, G. & Cairney, J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. (2015).

Mokkink, L. B. et al. COSMIN risk of bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual. Life Res. 27, 1171–1179 (2018).

Lopez-Soriano, M., Merenda, R., Esteves Trindade, V., Luna, P. H. L., Pairis-Garcia, M. D. & S. P., & Efficacy of transdermal flunixin in mitigating castration pain in piglets. Front. Pain Res. 3, 1056492 (2022).

Lopez-Soriano, M. et al. Efficacy of inguinal buffered lidocaine and intranasal flunixin meglumine on mitigating physiological and behavioral responses to pain in castrated piglets. Front. Pain Res. 4, 1156873 (2023).

Lin-Schilstra, L. & Ingenbleek, P. T. Examining alternatives to painful piglet castration within the contexts of markets and stakeholders: A comparison of four EU countries. Animals 11 (2), 486 (2021).

Neary, J. M., Porter, N. D., Viscardi, A. V. & Jacobs, L. Recognizing post-castration pain in piglets: A survey of swine industry stakeholders and the general public. Front. Anim. Sci. 3, (2022).

Trindade, P. H. E., de Araújo, A. L. & Luna, S. P. L. Weighted pain-related behaviors in pigs undergoing castration based on multilevel logistic regression algorithm. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 265, (2023).

da Silva, G. V. et al. Simplified assessment of castration-induced pain in pigs using lower complexity algorithms. Sci. Rep. 13, (2023).

Trindade, P. H. E., de Mello, J. F. S. R., Silva, N. E. O. F. & Luna, S. P. L. Improving ovine behavioral pain diagnosis by implementing statistical weightings based on logistic regression and random forest algorithms. Anim. (Basel) 12, 2940 (2022).

Livingston, F. Implementation of Breiman’s random forest machine learning algorithm. ECE591Q Mach. Learn. J. Paper, 1–13 (2005).

Choi, R. Y., Coyner, A. S., Kalpathy-Cramer, J., Chiang, M. F. & Campbell, J. P. Introduction to machine learning, neural networks, and deep learning. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 9 (2), 14–14 (2020).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Lee, T. H., Ullah, A. & Wang, R. Bootstrap aggregating and random forest. Macroeconom. Forecast. Era Big Data Theory Pract. 389–429 (2020).

Altman, D. G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1991).

Mahfuz, S., Dilawar, M. A., Yang, C. J. & Mun, H. S. Applications of smart technology as a sustainable strategy in modern swine farming. Sustainability 14, 2607 (2022).

Bateson, M. & Martin, P. Measuring Behaviour: an Introductory Guide (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

Coutant, M. et al. Administration of procaine-based local anaesthetic prior to surgical castration influences post-operative behaviours of piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 258, 105813 (2023).

Park, R. M. et al. A comparison of behavioural methodologies utilised to quantify deviations in piglet behaviour associated with castration. Anim Welf. 29 (3), 285–292 (2020).

Hay, M., Vulin, A., Génin, S., Sales, P. & Prunier, A. Assessment of pain induced by castration in piglets: behavioral and physiological responses over the subsequent 5 days. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 82, 201–218 (2003).

Moya, S. L., Boyle, L. A., Lynch, P. B. & Arkins, S. Effect of surgical castration on the behavioural and acute phase responses of 5-day-old piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 111 (1–2), 133–145 (2008).

Taylor, A. A., Weary, D. M., Lessard, M. & Braithwaite, L. Behavioural responses of piglets to castration: the effect of piglet age. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 73, 35–43 (2001).

Manteca, X., Da Silva, C. A., Bridi, A. M. & Dias, C. P. Animal welfare: concepts and practical procedures to evaluate the swine productions systems. Sem. Ciências Agrárias (Londrina) 34 (2), 4213–4229 (2013).

Broom, D. M. The use of the concept animal welfare in European conventions, regulations and directives. Food Chain 148–151 (2001).

Broom, D. M. Coping, stress and welfare. Coping with challenge: Welfare in animals including humans, 1–9. (2001).

Barnett, J. L. & Hemsworth, P. H. The validity of physiological and behavioural measures of animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 25 (1–2), 177–187 (1990).

Wemelsfelder, F. & Putten, G. Van. Behaviour as a possible indicator for pain in piglets. (1985).

Herskin, M. S. & Di Giminiani, P. Pain in pigs: characterisation, mechanisms and indicators. Adv. Pig Welf. 325–355 (2018).

Parsons, R. L. et al. Sow behavioral responses to transient, chemically induced synovitis lameness. Acta Agric. Scand. A: Anim. Sci. 65, 122–125 (2015).

Norscia, I., Collarini, E. & Cordoni, G. Anxiety behavior in pigs (Sus scrofa) decreases through affiliation and may anticipate threat. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 630164 (2021).

Arendt-Nielsen, L. et al. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. Eur. J. Pain (UK) 22, 216–241 (2018).

Hohenschurz-Schmidt, D. J. et al. Linking pain sensation to the autonomic nervous system: the role of the anterior cingulate and periaqueductal Gray resting-state networks. Front. Neurosci. 14, (2020).

Jänig, W. Sympathetic nervous system and inflammation: a conceptual view. Auton. Neurosci. 182, 4–14 (2014).

Rollin, B. E. Animal pain. In Advances in Animal Welfare Science (91–106), (Springer, 1985).

Trindade, P. H. E., Taffarel, M. O. & Luna, S. P. L. Spontaneous behaviors of post-orchiectomy pain in horses regardless of the effects of time of day, anesthesia, and analgesia. Animals 11 (6), 1629.55 (2021).

Trindade, P. H. E., da Silva, G. V., de Oliveira, F. A. & Luna, S. P. L. Ranking bovine pain-related behaviors using a logistic regression algorithm. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 106163 (2024).

Sober, E. The principle of parsimony. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 32 (2), 145–156 (1981).

Lou, M. E. et al. The application of 3D landmark-based geometric morphometrics towards refinement of the piglet grimace scale. Animals 12 (15), 1944 (2022).

Coutant, M., Malmkvist, J., Kaiser, M., Foldager, L. & Herskin, M. S. Piglets’ acute responses to local anesthetic injection and surgical castration: effects of the injection method and interval between injection and castration. Front. Vet. Sci. 9, 1009858 (2022).

Trindade, P. H. E., Lopez-Soriano, M., Merenda, V. R., Tomacheuski, R. M. & Pairis-Garcia, M. D. Effects of assessment method (real-time versus video-recorded) on a validated pain-altered behavior scale used in castrated piglets. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 18680 (2023).

Hewson, C. J., Dohoo, I. R., Lemke, K. A. & Barkema, H. W. Canadian veterinarians’ use of analgesics in cattle, pigs, and horses in 2004 and 2005. Can. Vet. J. 48 (2), 155 (2007).

Ison, S. H., Clutton, R. E., Di Giminiani, P. & Rutherford, K. M. D. A review of pain assessment in pigs. Front. Vet. Sci. (2016).

Benjamin, M. & Yik, S. Precision livestock farming in swine welfare: a review for swine practitioners. Animals 9 (4), 133 (2019).

Sadeghi, E., Kappers, C., Chiumento, A., Derks, M. & Havinga, P. Improving piglets health and well-being: A review of piglets health indicators and related sensing technologies. Smart Agric. Technol. 100246 (2023).

Čandek-Potokar, M., Škrlep, M. & Zamaratskaia, G. Immunocastration as alternative to surgical castration in pigs. Theriogenology 6, 109–126 (2017).

Povod, M., Lozynska, I. & Samokhina, E. Biological and economic aspects of the immunological castration in comparison with traditional (surgical) method. Bulgarian J. Agric. Sci. 25, 403–409 (2019).

Secretarária de defesa. agropecuária, do Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Instrução Normativa nº 113/2020, de 16 de dezembro de 2020. Dispõe sobre as boas práticas de manejo nas granjas de suínos de criação comercial. Disponível https://cleandrodias.com.br/legislacaobemestarsuinos/em (2024).

Lin-Schilstra, L. & Ingenbleek, P. T. A complex ball game: piglet castration as a dynamic and complex social issue in the EU. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 35 (3), 11 (2022).

Percie, D. et al. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000411 (2020).

Russell, W. & Burch, R. The principles of humane experimental technique. (1959).

Banks, R. E. The 4th R of research. Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 34 (1), 50–51 (1995).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (2022).

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. An introduction to statistical learning. 112, 18 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GMP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data visualization, Investigation, Writing—original draft and Writing—review & editing; GVS: Investigation and Writing—review & editing; BGP: Writing—review & editing; SPLL: Investigation and Writing—review & editing; MDPG: Investigation and Writing—review & editing; PHET: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft and Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pivato, G.M., da Silva, G.V., Peres, B.G. et al. Proposing a short version of the Unesp-Botucatu pig acute pain scale using a novel application of machine learning technique. Sci Rep 15, 7161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91551-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91551-6