Abstract

The biological complexity of wellbeing is studied from various perspectives, including genetics and epigenetics. However, there is a knowledge gap concerning other layers, such as metabolomics, which is dynamic and changes throughout life. This study explores the association between metabolites and wellbeing in a sample (N = 4748) drawn from the Netherlands Twin Register. A latent factor score for wellbeing was constructed based on: Quality of Life, Life Satisfaction, and Subjective Happiness. A total of 231 blood metabolites were analyzed using 1HNMR technique. Linear regression models were performed for each metabolite, while correcting for family clustering, relevant covariates, and multiple testing. None of the metabolites were significantly associated with wellbeing after multiple testing correction. Despite the lack of significant findings, the 34 metabolites with the lowest p-value (0.25) pointed to the same metabolic pathway: endogenous lipid metabolism. This pathway has previously been linked to wellbeing in a GWAS and associated with related phenotypes in other metabolomic studies. In conclusion, this study confirms the biological complexity of wellbeing and speculates on a potential role of lipids. Further research is needed to confirm these hypotheses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wellbeing (WB) is defined by the World Health Organization as a positive state experienced by individuals and societies, determined by social, economic, and environmental factors1. In light of major demographic trends (e.g. aging populations, increasing longevity, decreasing birth rates, increasing inequality, and unforeseen pandemics), building and maintaining WB is one of the most important societal challenges. People who feel well, function better, are less susceptible to mental illness, and thus are better able to retain competitive advantage and expand human potential2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Different conceptualizations of wellbeing exist, the most common distinction is between subjective wellbeing (SWB) and psychological wellbeing (PWB), also known as hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing, respectively9,10,11. Correlations between these (latent) SWB and PWB factors are often so high that it is difficult to distinguish between them (∼ 0.60–0.9010,12,13,14). The current study focuses, due to data availability, on SWB, defined as the cognitive and affective evaluation of one’s life. In this paper, for readability purposes, we refer to SWB as wellbeing (WB).

WB is a complex phenotype influenced by various factors, including biological factors, such as genetic and epigenetic mechanisms15. Some of these biological factors—referred to as omics layers—are very stable across life, such as the genome. Previous studies have highlighted the significant role of genomics in WB. For instance, a Genome-Wide Association Study identified 304 significant independent SNPs associated with WB16, demonstrating the genetic underpinnings of this trait. Additionally, a polygenic score for WB, assessed by Baselmans et al. (2019), explained between 0.62% and 0.76% of the variance observed in WB17. Such findings provide valuable insights into the biological complexity underlying WB and emphasize the potential of molecular studies to deepen our understanding of this trait.

Other omics layers are subjective to changes by the environment or other conditions, e.g. epigenomics, transcriptomics, or metabolomics. The role of epigenomics in WB has also been studied. An Epigenome-Wide Association Study for WB reported also two significant sites after Bonferonni correction18. Given these differences in characteristics, each omics layer can provide unique information about a trait of interest. For example, the metabolome that summarizes a given metabolic state of the body19. Metabolites are molecules involved in or produced by biological processes, including digestion and other biochemical reactions19 and the fact they are dynamic offers an interesting target for biological studies, intervention, and facilitating the implementation of more personalized medicine approaches20,21.

Knowledge about the influence of omics layers beyond genomics or epigenomics on WB is currently lacking. A potential positive association between the neurotransmitter serotonin and WB (i.e., hedonic wellbeing) was revealed in a systematic review, but evidence on the role of other small molecules—including metabolites—was inconclusive22. In addition, the precise interactions among these metabolites within the context of WB are not well understood and require further investigation.

Although metabolomics studies on wellbeing are lacking, Radler et al.23 investigated the relationship between three types of lipids and psychological wellbeing—a construct related but not synonymous to subjective wellbeing, which is the focus of the current paper. Over a follow-up period of 9–10 years, persistently high levels of psychological wellbeing were associated with elevated HDL cholesterol and reduced triglyceride levels23.

Despite the absence of metabolomics studies for WB, interesting results have been observed in related phenotypes such as perceived stress and mental health. Noerman et al. showed associations between phosphatidylcholines and several parameters indicating stress, and found changes in a group labelled as “unknown class of lipids” over time to be correlated with physiological and psychological markers of stress24. Jia et al. studied individuals with high and low depression and assessed cognitive skills and serum lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol)25. In the low depression group, they found that the lower the LDL levels, the higher the cognitive scores. This may indicate that LDL could negatively affect cognitive skills, at least for individuals with low depressive symptoms. In addition, Bot et al.26 also reveals a distinct profile of circulating lipid metabolites linked to depression in a large-scale meta-analysis.

A related phenotype that has also been studied in metabolomics studies is Type D (Distressed) personality, characterized by negative affectivity (NA) and social inhibition. Li-Gao et al.27 explored the associations between metabolite profiles and these personality traits in four Dutch cohorts. There were no substantial alterations in lipid metabolism linked to these traits27 although their findings suggest that some metabolite biomarkers showed tentative associations with Type D personality and NA. In general, effect sizes were small.

Summarizing, the aforementioned studies of Noerman et al.24, Jia et al.25 and Bot et al.26 combined with the meta-analysis results from de Vries et al.22 suggest that studying the association between metabolites in the context of wellbeing is of interest to better understand the interplay between metabolite concentrations and differences in WB. Therefore, we aim to test whether metabolites are associated with WB to increase our understanding of their biological interpretation concerning WB.

Materials and methods

This study was preregistered at the Open science framework platform (https://osf.io/4s2mu/).

Participants

Participants included in this study are part of the Netherlands Twin Register (NTR), a population-based national register of twins and their families with extensive data collection on, amongst other things, mental health, personality, lifestyle, and demographics28—proven to be representative of the Dutch population29. Participants have been recruited since 1986, after which questionnaires have been collected every 2–3 years. In addition to questionnaires, biological samples were collected between 2004 and 2010. The questionnaires, biological sampling, processing, and storage are described in previously published work28,30. In this study, we utilized surveys 6 (2006–2007), 8 (2009–2010), 10 (2013–2014), and 14 (2019–2020) to select a wellbeing measure optimally linked to the biological sample collection.

The data used in this study were obtained from the NTR after meeting the requirements posited by the NTR Data Management and the NTR Data Sharing Committee and obtaining their permission. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. Data collection was approved by the Central Ethics Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects of the University Medical Centers Amsterdam. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

A sub-sample from the NTR biobank (N = 4748) was selected with available metabolomics and wellbeing data. Note that in the pre-registration there were 5398 individuals with metabolomic data. When the data was inspected, 650 individuals had missing data for all the metabolites and therefore they were excluded. The mean survey age was 40.6 [standard deviation (SD) 14.0, range 14–82 years], for 18 participants age was missing. The mean biological data age was 40.6 [standard deviation (SD) 13.6, range 18–79 years]. The ratio of men/women was 1536 (32%) /3210 (68%); 2 individuals did not report their sex.

Measures

Wellbeing

Wellbeing was assessed as a continuous trait with three measures, i.e. Quality of Life with the Cantril Ladder (QoL31), the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS32), and the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS33). Quality of Life was assessed with the Cantril Ladder, which requires participants to indicate the step of the ladder at which they place their lives in general on a 10-point scale (10 being the best possible life, and 1 the worst possible life)31. The SWLS consists of five items answered on a seven-point scale ranging from 1=“strongly disagree” to 7=“strongly agree”32. An example item is: “I am satisfied with my life”. The SHS consists of four items which rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 1=“strongly disagree” to 7=“strongly agree”33. An example item is “On the whole I am a happy person”.

The different wellbeing measures were used in various surveys. QoL was part of survey 8, 10 and 14, SWLS was part of all surveys, while SHS was part of surveys 6, 8, 14. For SWLS and SHS the items—5 items for SWLS, 4 for SHS—were summed to arrive at a sum score for each measure. Where necessary, inversion of item scores was done to ensure that for each variable a higher score indicated higher wellbeing levels. The sum scores for QoL, SWLS and SHS were first transformed into Z-scores to avoid scaling issues when creating the latent factor score. Reliability (internal consistency) coefficients were adequate to high, for the SHS ranging from 0.76 (survey 8) to 0.89 (survey 14) and for the SWLS ranging from 0.86 (survey 6) to 0.88 (survey 8). For the single QoL items, reliability was assessed through test-retest correlations for those with longitudinal information. Correlations were 0.46 (between survey 8 and 10 and between survey 8 and 14) and 0.55 (between survey 10 and 14), in line with typical stability coefficients found34.

Previous studies have demonstrated the validity of this latent factor score. It has been used to investigate associations between wellbeing in a multi-omics study, including the genome, epigenome, and exposome, using machine learning approaches35. Additionally, it has been considered to differentiate wellbeing from depressive symptoms36. Furthermore, it has been proposed as a more suitable alternative in a study by Baselmans et al.37, that did not adopt its use.

In each wave, a single factor score for wellbeing was built on all available wellbeing measures (differences in number of available measurements per wave did not affect factor scores, see Supplementary information) using structural equation modeling38. We used full information maximum likelihood when constructing the factor score, which can handle missing values on indicator variables. However, to limit the number of missing values per participant, only those with at least two out of three measurements per wave were included. To reduce bias, a transformation was used so that the covariance matrix of the estimated factor scores matched the model-based latent factor covariance matrix39,40. Reliability of the factor scores were calculated using McDonald’s omega coefficient, which were all high, ranging between 0.80 (survey 10) and 0.91 (survey 14), indicating that a large share of score variance is due to the underlying factor.

Metabolomics data

231 metabolic markers were quantified from plasma samples using high-throughput proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy 1H-NMR) metabolomics (Nightingale Health Ltd, Helsinki, Finland; formerly Brainshake Ltd.). This method provides simultaneous quantification of lipids, lipoprotein subclass profiling with lipid concentrations within 14 subclasses, fatty acid compositions, and various low molecular weight metabolites including amino acids, ketone bodies, and glycolysis-related metabolites in molar concentration units41. Variables representing percentages of metabolites instead of the actual concentrations were removed to avoid collinearity. The final dataset contained 148 metabolites and 9 ratios, shown in Supplementary Table 1. All the variables were scaled to allow comparisons of findings. Four metabolites—FALen, UnsatDeg, UnSat, Gln—were missing in most of the participants (31, 31, 88, and 100%, respectively) resulting in a final set of 144 metabolites and 9 ratios for analyses. Note that 102 out of the 157 metabolites fall under the category of lipoproteins. Biological samples were obtained following the standard procedure for such collections. Plasma samples were stored at −20 °C. A comprehensive overview of the biobank procedures for blood sample collection is provided in Willemsen et al.42 and Ligthart et al.43.

The Nightingale Health 1HNMR platform protocol is as follows: Before the NMR measurements, samples are mixed with a sodium phosphate buffer (75 mmol/L Na2HPO4 in 80%/20% H2O/D2O, pH 7.4; including also 0.08% sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl)propionate-2,2,3,3-d4 and 0.04% sodium azide) and moved to the NMR tubes. A PerkinElmer JANUS Automated Workstation with an 8-tip dispense arm with Varispan is responsible for the liquid handling. Samples are transferred to 96- well plates, with every plate includes two quality control (QC) samples (consistency of quantifications), a serum mimic and a mixture of two low-molecular–weight metabolites (performance automated liquid handler and spectrometer). The laboratory setup combines a Bruker AVANCE III 500 MHz and Bruker AVANCE III HD 600 MHz spectrometers, both with the SampleJet robotic sample changer. The 500 MHz spectrometer is furnished with a selective inverse room temperature probe head, the 600 MHz spectrometer is furnished with a cryogenically cooled triple resonance probe head (CryoProbe Prodigy TCI). The 500 MHz and 600 MHz spectrometers can both automatically collect the lipoprotein (LIPO) and low-molecular-weight metabolites (LMWM) with standardized parameters. After spectroscopy, the samples are processed manually with a standardized lipid extraction procedure with multiple extraction steps using an Integra Biosciences VIAFLO 96 channel electronic pipette. These lipid extracts are again analyzed, in full automation, with the 600 MHz spectrometer with a standard parameter set. Initial data processing is handled by the computers controlling the spectrometers. Processing includes automated phasing and Fourier transformation of the NMR spectra. In house-algorithms located on a centralized server process the spectral data further, which includes baseline removal, background control, checking for missing or extra peaks, and spectral area-specific signal alignments. Regression modelling is performed to quantify the molecular data for those spectral areas that pass QC.

Data selection

To reduce bias of changes over time, we aimed to keep the time between the biological sample collection and the survey as short as possible. Therefore, the wellbeing latent score with the least time between phenotype assessment and biological sample collection was selected. The final sample consists of 4748 individuals, with 2198 individuals with data from survey 6, 2318 with data from survey 8, 199 from survey 10 and 33 from survey 14. The average time difference between the survey data and the biological data collection (time difference) was 2.49 years (SD = 0.89).

Covariates

All models were adjusted for BMI, smoking status, fasting status, medication use (lipid-lowering, statin, hypertension, beta blocker, cardiac or antidepressive medication), time difference, and batch effects since these are variables that could affect the metabolite levels and/or measurements44. A descriptive table of the sample per batch is shown in Supplementary Table 4.

The mean BMI of the sample was 24.7 (SD = 4.1). Smoking status was reported from the participants as no smokers (2515; 53%), former smokers (1307; 28%), and current smokers (912; 19%), while 14 individuals did not report smoking information. In total, 4479 (96%) samples were taken in a fasting state (data were missing for 72 participants), and 422 (9%) were using medication at the moment of the biological data collection.

To test whether the confounders included in the model of interest influence the variability in metabolite concentrations (collectively), Principal Component Partial R-square was used45. Since we cannot create a separate model for each metabolite with specific confounders, this approach allowed us to determine the overall relationship between the confounders and the metabolite concentrations.

Statistical analyses

The removal of the variables for the metabolite percentages as well as the merging of the metabolite measures with the covariates were performed in Python 3 and the statistical analyses were performed in R, version 4.3.2. The main packages used were pandas for Python and foreign46, lavaan47, gee48, pcpr249 for the statistical analyses in R.

Multiple linear regression in generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used to determine the associations between the wellbeing score as the independent variable and concentrations of metabolites as dependent variables. GEE models allow to correct for non-independence of data introduced by twin status within families50. All models were adjusted for BMI, smoking status, fasting status, medication use, time difference, and batch effect. As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated this regression analysis with a time difference limit of 5 years. This sensitivity analysis was not pre-registered. Although not pre-registered, we conducted additional analyses including sex and age as covariates due to their relevance to metabolite variation51.

After correction for multiple testing, using false discovery rate (FDR) according to the Benjamin-Hochberg procedure52,53, a p-value (pFDR) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

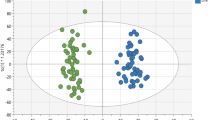

The GEE models showed 52 significant associations between metabolites concentrations and wellbeing before FDR correction (p < 0.05). After the correction, no significant association remained (pFDR < 0.05). The p-values (before and after correction) as well as the direction of the effect—determined by the standardized β—are shown in Fig. 1.

Associations between metabolite concentrations and wellbeing before and after multiple testing correction. P value vs. standardized beta before (left) and after (right) FDR correction. -log10 of P value in the Y axis and standardized beta on the X axis. A threshold is set at 0.05 with a dotted line. Significant p values are shown in purple.

Given the absence of significant metabolites, we focused on the lowest p-value metabolites associated with wellbeing. After the p-value correction, 34 metabolites presented the same p-value (pFDR = 0.246), which was also the closest p-value to the significance threshold (0.05). The biological classification for all metabolites, and results of the GEE models for the 34 metabolites with top pFDR are described in Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. Out of these 34 variables, 28 are of the class of lipoproteins, 2 are cholesterols, 2 glycerides and phospholipids, 1 is a lipoprotein, and 1 is of class “fluid balance”. Standardized beta values and their CI are represented in Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the metabolites with the lowest p-value after correction (0.2456) from higher beta to lower colored by metabolite class (legend on the bottom). On the right the description of the metabolite. Note: when correction of p-value, only the p-value is corrected. For this reason, the metabolites are not significant even though their confidence intervals do not cross the 0 value.

These regressions were repeated with a limited time difference between the blood sample collection and the survey collection of 5 years. This constraint resulted in a reduction in sample size of 4.93%—4514 individuals remained. However, no notable differences with the main analyses were observed (see Supplementary Analyses and Supplementary Table 3). The additional analyses incorporating sex and age as covariates did not alter the results; no significant metabolites were identified (P > 0.05).

The PCA R2 analysis showed that 21.35% of the variability in metabolite concentrations—all taken together—was explained by the confounders in the model of interest; BMI, smoking status, fasting status, medication use, time difference between biological and survey collection, and batch effect. The variability explained by each of the covariates as well as the total, is shown in Fig. 3.

Discussion

We studied the relationship between metabolites and wellbeing in a sample drawn from the Netherlands Twin Register (NTR). Our results showed no significant associations between metabolite concentrations or ratios and wellbeing after multiple testing corrections, but provided an interesting proof of concept of the complexity of the biology of wellbeing.

As far as we know, our study is the first focusing on the association between metabolites and wellbeing, which prevents us from directly comparing our results with previous work. In this study, from the original 148 metabolites, 34 metabolites were reported with the same lowest p-value after FDR correction (pFDR = 0.24563). These are mainly (apo)lipoproteins and cholesterol molecules. A significant proportion of the data consisted of lipoproteins (102 out of 157 metabolites), making it likely that any false positives observed prior to multiple testing corrections would originate from this category. Given the fact that they were not statistically significant, we hypothesize a broad explanation of their role in the biology of wellbeing, regardless of the size of the molecules and the specific parameters for each molecule.

All the 34 metabolites mentioned above take part in the endogenous lipid metabolism: the lipoproteins (Very Low Density Lipoprotein (VLDL), Intermediate Density Lipoprotein (IDL), Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL), and High Density Lipoprotein (HDL)), the apolipoproteins (Apo B) and phospholipids (Triglycerides and Sphingomyelins) closely related to them, the free cholesterol (Free Cholesterol), and even albumin (in charge of lipid transportation in blood54) can be connected to this pathway, illustrated in Fig. 4. In general, lipids are essential for cell structures and to generate energy in the cell19.

The liver synthesizes Triglycerides and cholesterol, which circulate in VLDL lipoproteins containing ApoB and sphingomyelin. These VLDLs transport lipids to tissues, where they release Triglycerides and transform into IDLs and LDLs, carrying cholesterol. LDLs return cholesterol to the liver or tissues, but excess LDLs can oxidize, leading to atheroma formation, earning them the label "bad cholesterol." Conversely, HDLs, containing ApoA1 and sphingomyelin, gather excess cholesterol and transport it back to the liver for disposal, earning them the moniker “good cholesterol”.

An hypothesis previously stated in the literature is that a healthier lifestyle is associated with a happier life55. “Bad” cholesterol—transported by LDL—and the associated molecules can have a negative effect on the cardiovascular system and are associated with a poorer lifestyle56. While the “good” cholesterol molecules—transported by HDL and associated with a healthy and balanced lifestyle—can have a positive effect on the cardiovascular system56. In line with this hypothesis, we found the βs for LDL to be negative while the βs for HDL were positive, which implies that the lower the LDL or the higher the HDL parameters, the higher wellbeing levels are reported. However, as the results were not significant they are suggestive, warranting caution in their interpretation and additional research for replication.

This potential effect of lipid metabolism on wellbeing is in line with previous results in other wellbeing omics, such as genomics. Baselmans et al. found in a Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) for wellbeing a significant effect of a SNP (rs10838629) associated with the LDL receptor (LDL receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4))16. In another study from Turley et al. (2018), there are also some significant SNPs for wellbeing that are associated with lipid-related molecules, such as LDL receptor-related protein 1B (LRP1B, rs10197004) and Apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1, rs61905145)57. Therefore, the hypothesized pathway standing out in our results is in line with the same pathway reported in previous genetic studies for wellbeing.

Metabolomics results of other phenotypes closely related to wellbeing are worth discussing here. Noerman et al. found associations between phosphatidylcholines and several parameters indicating subjective stress. They also observed that changes in an unknown class of lipids over time correlate with physiological and psychological markers of stress24. Unfortunately, we did not include phosphatidylcholines or so-called “unknown class of lipids” parameters and, therefore, results cannot be compared directly.

As noted, Jia et al., suggested that serum lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol) may be linked directly to self-rated depression and cognitive performance25. For the low depression group, they found that the lower the LDL levels, the higher the cognitive scores. Although the phenotype is not exactly similar to the current study hypothesizes, an effect of the cholesterol pathway is observed. LDL, specifically, is present in the top metabolites subset observed in the present study and with the same (potential) direction of effect. The pattern observed in the discussed studies investigating metabolites in relation to wellbeing and mental health, is that lipids may play a role in wellbeing or related phenotypes compared to the other large molecule groups—proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates. Thus, future research should focus on lipids in studies with a bigger sample size to unravel the potential relationship between lipid concentrations and wellbeing.

There are notable limitations in this study that require consideration. Firstly, the biological samples were not collected on the same day as the surveys were filled out with a time difference between 2 and 13 years (average of 2.49 years, SD = 0.89) with the biological sampling, potentially introducing bias in identifying metabolites associated with wellbeing. Unlike the genome, metabolite levels are highly dynamic. Even though wellbeing is assumed to be relatively stable across time34,58,59,60,61,62, differences between the time of biological sample and survey collection may have influenced our results, since metabolite concentrations change over time and conditions20,21. Sensitivity analyses with a time difference below 5 years, resulting in a reduction in sample size of 4.93%—4514 individuals remained –, did not result in notable differences with the main analyses (see Supplementary Analyses and Supplementary Table 3). In addition, the PCA R2 showed that only 0.13% of the variance in the total set of metabolites was explained by the time difference. Still, we cannot rule out that our results are partly influenced by differences in data collection between individuals. Regarding the time difference between blood collection and analyses, access to this specific data was not provided. However, as outlined in Willemsen et al.42, the samples were stored under appropriate conditions. Secondly, this is a cross-sectional study—i.e., unable to assess causality—only able to reveal associations. Third, the focus on lipids in the available data may overlook important insights from other metabolite classes that were not covered with the used technique. Lastly, surveys 6 and 10 had only two measurements available instead of 3, which meant that the factor scores of survey 6 and 10 could have been less reliable than the others. However, we found that the correlations between all the factor scores were not significantly different from each other (Supplementary information), meaning that there was no bias introduced by the survey used.

Conversely, this study presents several strengths. The sample size is substantial for a study of this nature (N = 4748). The variables included in the models as covariates were also found to be important to include, given the results of the analysis. The PCA-R2 analysis showed that 21% of the variability observed in the metabolites is accounted for by the covariates. This underlines the importance of correcting for them, as done in this study.

A challenge with testing for associations between metabolites and an outcome is that many metabolites are correlated. Having several, correlated measurements for the same molecule or set of molecules—in combination with multiple testing correction—might have acted to our disadvantage. Alternatively, by reducing the number of subtypes per molecule, the multiple-testing burden could be lowered, although it is hard to decide a priori which measurements should be taken. Rather than selecting fewer measurements per molecule, data reduction techniques could be applied to find subgroups of metabolites associated with the outcome of interest63. However, data reduction techniques always imply losing information and may complicate the biological interpretability of obtained results64.

Future investigations should focus on lipids, examining lipoproteins regardless of their subtype or other parameters should be considered, preferably in an even larger sample. Alternatively, one could include other classes of metabolites, not covered by the used technique in this study, to confirm that the recommended focus on lipids is appropriate. Additionally, data from other biological layers should be included to do an integrative multi-omics framework in the future, promising a deeper understanding of their interactions in determining wellbeing. Other methods like systems biology approaches (e.g. pathway analysis) should be considered in future research with significant results. Future investigations should explore these findings in larger and broader samples to assess their generalizability and potential new insights.

In conclusion, in this study, it is speculated that lipids may play a role in the metabolism of wellbeing, but more research including other omics is necessary to disentangle the complex biology of wellbeing.

Data availability

Being part of a national prospective cohort study, Netherlands Twin Register data cannot be made publicly available for privacy reasons, but they are available for legitimate researchers via the data access procedure (https://ntr-data-request.psy.vu.nl/). The research data collected by the Netherlands Twin Registry (NTR) are pseudonymized, annotated, and stored in the NTR Repository. This is a secure database that is only accessible to our data managers. Metadata (i.e. variable names, labels, counts etc.) can be consulted by researchers in the NTR Data Showcase (https://ntr-data-request.psy.vu.nl/data-showcase.html). The Data Showcase allows researchers to create a list of variables and export it for use in a Data Sharing Request (https://ntr-data-request.psy.vu.nl/submitting-a-data-sharing-request.html). Researchers with an approved data sharing request who abide by the rules of the European General Data Protection Regulation will receive temporary access to the NTR data for their own research projects. More information on our data-sharing procedures and associated costs can be found https://ntr-data-request.psy.vu.nl/data-sharing-procedures.html. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

References

Nutbeam, D. & Muscat, D. M. Health promotion glossary 2021. Health Promot. Int. 36, 1578–1598 (2021).

Chapman, B. & Guven, C. Revisiting the relationship between marriage and wellbeing: does marriage quality matter?? J. Happiness Stud. 17, 533–551 (2016).

James, P. et al. Optimism and healthy aging in women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 56, 116–124 (2019).

Kim, E. S. et al. Optimism and healthy aging in women and men. Am. J. Epidemiol. 188, 1084–1091 (2019).

Maccagnan, A., Wren-Lewis, S., Brown, H. & Taylor, T. Wellbeing and society: towards quantification of the co-benefits of wellbeing. Soc. Indic. Res. 141, 217–243 (2019).

Oswald, A. J., Proto, E. & Sgroi, D. Happiness and productivity. J. Labor Econ. 33, 789–822 (2015).

Steptoe, A. Happiness and health. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 40, 339–359 (2019).

Walsh, L. C., Boehm, J. K. & Lyubomirsky, S. Does happiness promote career success? Revisiting the evidence. J. Career Assess. 26, 199–219 (2018).

Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95, 542–575 (1984).

Keyes, C. L. M. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J. Health Soc. Behav. 43, 207–222 (2002).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 141–166 (2001).

Joshanloo, M. Revisiting the empirical distinction between hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-being using exploratory structural equation modeling. J. Happiness Stud. Interdiscip. Forum Subj. Well-Being 17, 2023–2036 (2016).

Gallagher, M. W., Lopez, S. J. & Preacher, K. J. The hierarchical structure of well-being. J. Pers. 77, 1025–1050 (2009).

Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., Kashdan, T. B., Short, J. L. & Jarden, A. Different types of well-being? A cross-cultural examination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Psychol. Assess. 28, 471–482 (2016).

Jamshidi, J., Schofield, P. R., Gatt, J. M. & Fullerton, J. M. Phenotypic and genetic analysis of a wellbeing factor score in the UK biobank and the impact of childhood maltreatment and psychiatric illness. Transl. Psychiatry. 12, 113 (2022).

Baselmans, B. M. L. et al. Multivariate genome-wide analyses of the well-being spectrum. Nat. Genet. 51, 445–451 (2019).

Baselmans, B. M. L. et al. A genetic investigation of the well-being spectrum. Behav. Genet. 49, 286–297 (2019).

Baselmans, B. M. L. et al. Epigenome-Wide association study of wellbeing. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 18, 710–719 (2015).

Fowler, S., Roush, R. & Wise, J. Concepts of Biology. (2013).

Schranner, D., Kastenmüller, G., Schönfelder, M., Römisch-Margl, W. & Wackerhage, H. Metabolite concentration changes in humans after a bout of exercise: a systematic review of exercise metabolomics studies. Sports Med. Open 6, 11 (2020).

Wittenbecher, C. et al. Changes in metabolomics profiles over ten years and subsequent risk of developing type 2 diabetes: results from the nurses’ health study. EBioMedicine 75, 103799 (2021).

de Vries, L. P., van de Weijer, M. P. & Bartels, M. The human physiology of well-being: A systematic review on the association between neurotransmitters, hormones, inflammatory markers, the microbiome and well-being. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 139, 104733 (2022).

Radler, B. T., Rigotti, A. & Ryff, C. D. Persistently high psychological well-being predicts better HDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels: findings from the midlife in the U.S. (MIDUS) longitudinal study. Lipids Health Dis. 17, 1 (2018).

Noerman, S. et al. Plasma lipid profile associates with the improvement of psychological well-being in individuals with perceived stress symptoms. Sci. Rep. 10, 2143 (2020).

Jia, Q. et al. The role of lipoprotein profile in depression and cognitive performance: a network analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 20704 (2020).

Bot, M. et al. Metabolomics profile in depression: A pooled analysis of 230 metabolic markers in 5283 cases with depression and 10,145 controls. Biol. Psychiatry. 87, 409–418 (2020).

Li-Gao, R. et al. Metabolomics profiling of type D personality traits. J. Psychosom. Res. 188, 111994 (2025).

Ligthart, L. et al. The Netherlands twin register: longitudinal research based on twin and twin-Family designs. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2019.93 (2019).

Vink, J. M. et al. Estimating non-response bias in family studies: application to mental health and lifestyle. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 19, 623–630 (2004).

Willemsen, G. et al. The adult Netherlands twin register: twenty-five years of survey and biological data collection. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. Off J. Int. Soc. Twin Stud. 16, 271–281 (2013).

Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns (1965).

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75 (1985).

Lyubomirsky, S. & Lepper, H. S. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 46, 137–155 (1999).

Anusic, I. & Schimmack, U. Stability and change of personality traits, self-esteem, and well-being: introducing the meta-analytic stability and change model of retest correlations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110, 766–781 (2016).

Pelt, D. et al. Building machine learning prediction models for wellbeing using predictors from the phenome, genome, and exposome in a population cohort. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/fsq3j (2023).

de Vries, L. P. et al. Distinguishing happiness and meaning in life from depressive symptoms: A GWAS-by-subtraction study in the UK biobank. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 195, e32954 (2024).

Baselmans, B. M. L. et al. Unraveling the genetic and environmental relationship between Well-Being and depressive symptoms throughout the lifespan. Front. Psychiatry 9 (2018).

Bartels, M., Cacioppo, J. T., van Beijsterveldt, C. E. M. & Boomsma, D. I. Exploring the association between well-being and psychopathology in adolescents. Behav. Genet. 43, 177–190 (2013).

Croon, M. A. Using predicted latent scores in general latent structure models. In Latent Variable and Latent Structure Models (eds Marcoulides, G. A. & Moustaki, I.) 195–224 (Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002).

Devlieger, I. & Rosseel, Y. Factor score path analysis: an alternative for SEM? Methodology 13, 31–38 (2017).

Bharti, S. K. & Roy, R. Quantitative 1H NMR spectroscopy. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 35, 5–26 (2012).

Willemsen, G. et al. The Netherlands twin register biobank: A resource for genetic epidemiological studies. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 13, 231–245 (2010).

Ligthart, L. et al. The Netherlands twin register: longitudinal research based on twin and twin-family designs. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 22, 623–636 (2019).

Tokarz, J. & Adamski, J. Confounders in metabolomics. In Metabolomics for Biomedical Research 17–32 (Elsevier, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812784-1.00002-5

Fages, A. et al. Investigating sources of variability in metabolomic data in the EPIC study: the principal component partial R-square (PC-PR2) method. Metabolomics 10, 1074–1083 (2014).

R Core Team. foreign: Read Data Stored by ‘Minitab’, ‘S’, ‘SAS’, ‘SPSS’, ‘Stata’, ‘Systat’, ‘Weka’, ‘dBase’, ... (2023).

Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36 (2012).

Carey, V. J. gee: Generalized Estimation Equation Solver (2023).

Rothwell, J., Fages, A., Assi, N., Viallon, V. & Ferrari, P. pcpr2: The Principal Component Partial R-squared method (PC-PR2).

Minică, C. C., Boomsma, D. I., Vink, J. M. & Dolan, C. V. MZ twin pairs or MZ singletons in population family-based GWAS? More power in pairs. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 1154–1155 (2014).

Carroll, M. D. et al. Trends in serum lipids and lipoproteins of adults, 1960–2002. JAMA 294, 1773–1781 (2005).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Cambiaghi, A., Ferrario, M. & Masseroli, M. Analysis of metabolomic data: tools, current strategies and future challenges for omics data integration. Brief. Bioinform. 18, 498–510 (2017).

van der Vusse, G. J. Albumin as fatty acid transporter. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 24, 300–307 (2009).

Prendergast, K. B., Schofield, G. M. & Mackay, L. M. Associations between lifestyle behaviours and optimal wellbeing in a diverse sample of New Zealand adults. BMC Public. Health 16, 62 (2015).

Sun, T. et al. Predictive value of LDL/HDL ratio in coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 22, 273 (2022).

Turley, P. et al. Multi-trait analysis of genome-wide association summary statistics using MTAG. Nat. Genet. 50, 229–237 (2018).

Ehrhardt, J. J., Saris, W. E. & Veenhoven, R. Stability of life-satisfaction over time: analysis of change in ranks in a national population. J. Happiness Stud. Interdiscip. Forum Subj. Well-Being 1, 177–205 (2000).

Fujita, F. & Diener, E. Life satisfaction set point: stability and change. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 88, 158–164 (2005).

Lucas, R. E. & Donnellan, M. B. How stable is happiness? Using the STARTS model to estimate the stability of life satisfaction. J. Res. Personal 41, 1091–1098 (2007).

Pavot, W. & Diener, E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol. Assess. 5, 164–172 (1993).

de Vries, L. P., Pelt, D. H. M. & Bartels, M. The stability and change of wellbeing across the lifespan: a longitudinal twin-sibling study. Psychol. Med. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291724000692 (2024).

Hendriks, M. M. W. B. et al. Data-processing strategies for metabolomics studies. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 30, 1685–1698 (2011).

Shyam Mohan, J. S. & Data reduction techniques for high dimensional biological data. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 05, 319–324 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank all participating twins in the Netherlands Twin Register who dedicated part of their time to make research possible as well as everyone involved in the collection of the data and data management. This study is funded by an NWO-VICI grant (VI.C.211.054, PI Bartels). Prof Bartels is furthermore funded by an ERC Consolidator Grant (WELL-BEING; grant 771057). Data collection for this study has been funded by NWO large investment grant (NTR: 480-15-001/674), ZonMW Addiction program (31160008), ERC Consolidator Grant (WELL-BEING; grant 771057), NWO-MW 904-61-193, NWO 575-25-006, Genotype/phenotype database for behavior genetic and genetic epidemiological studies (ZonMw Middelgroot 911-09-032); the Biobank-based integrative omics study (BIOS) funded by BBMRI-NL (NWO projects 184.021.007 and 184.033.111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.G., A.J.M.R.G., D.H.M.P. and M.B. designed the study. N.A.G. performed the literature search and the analyses. N.A.G. drafted the manuscript with support from A.J.M.R.G., D.H.M.P. and R.P. A.J.M.R.G., D.H.M.P., and M.B. supervised the study. All authors have approved the submitted version and have agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration. Data collection was approved by the Central Ethics Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects of the University Medical Centers Amsterdam. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Ethical approval numbers are as follows: survey 6: 2001-069 (17-10-2001); 8: 2008-244 (01-12-2008); 10: 2011-334 (12-10-2011), 2012-433 (26-02-2013); 14: 2018-389 (25-07-2018) and for the biobank: 2003-180.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azcona-Granada, N., Geijsen, A.J.M.R., Pool, R. et al. The association between metabolite concentrations and wellbeing in adults. Sci Rep 15, 6997 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91558-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91558-z