Abstract

The massive thick overburden strata (MTOS) above the coal seam can result in high mining pressure in the stope, with significant manifestations of mine pressure, potentially triggering safety issues such as mine pressure bursts. In this paper, the fracture and migration characteristics of layered fracturing in MTOS above the stope were analyzed. The competitive fracture propagation mechanism in closely distances group fractures was revealed. Moreover, the layered group fracturing (LGF) technology for MTOS above the stope was proposed. The results showed that: LGF technology can reduce the caving step distance in the MTOS, and the formation of a “V”-shaped masonry beam structure by the fractured blocks provides effective support for the working face. Smaller fracture spacing leads to shorter initiation time for competitive fracture propagation within groups, and this competition is more intense. The superposition of the internal stress fields in the rock caused by fracture expansion is the fundamental reason for the “backward” competitive fracture propagation among group fractures. The field application results showed that LGF of MTOS can effectively reduce the intensity of periodic pressure on the working face, decrease the cycle pressure step distance, and lower the resistance of supports on the working face.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global energy demand continues to increase year by year, the depth of coal resource extraction and the scale of recovery are expanding, presenting greater challenges for safe and efficient production in mines1,2. A massive thick overburden strata (MTOS) refers to a rock layer or a combination of multiple similar rock layers above the coal seam, with a thickness ranging from tens to even hundreds of meters. Due to the significant thickness and strength of the MTOS, the surrounding stress field is much higher than that of ordinary working faces, by tens or even hundreds of times. Mining beneath a MTOS typically results in potential safety threats, such as large-scale roof collapse in the goaf, enormous support stress on the working face, significant roadway deformation, and the induction of rock burst hazards, which negatively impact the high-quality development of the mine3,4,5,6.

Hydraulic fracturing (HF) involves injecting high-pressure water into rock layers through drilled holes, which generates new fractures or extends existing cracks within the rock. This process aims to alter the overall structure of the rock layer and reduce the strength of the rock mass7,8. Compared to explosive fracturing methods, HF allows for precise control of fracture expansion by adjusting the injection pressure and volume, enabling modification of the rock structure while minimizing damage to the integrity of the rock layer. It can achieve structural alterations without causing large-scale, unnecessary damage to the rock. Moreover, because high-pressure water is used as the fluid medium, HF produces less disturbance to the overburden compared to the intense vibrations generated by blasting, making it a more environmentally friendly and greener option. Additionally, the equipment for HF is simple, easy to operate, and has lower initial investment costs9,10,11.

As a new type of rock layer fracture and stability control technology, HF has been widely applied in recent years for various purposes, including coal seam permeability enhancement12,13,14, roadway pressure relief15,16,17, and overburden fracturing in mining faces18,19,20. HF of the overlying rock layers above the safety coal pillar in retreat roadways. This improves the stress environment of the safety coal pillar, reduces the resistance of the support system in the mining face, decreases the width of the safety coal pillar, and increases the mining recovery rate21,22,23. HF of hard rock layers in the roadway boreholes to release the excessive stress in the surrounding rock, solving the issue of large deformations caused by the dynamic pressure from mining24. HF of the hard roof in the recovery roadway toward the adjacent mined-out areas. This cuts off the high-stress transfer path caused by the long-distance hanging roof of the mined-out area, reducing the accumulation of energy in the safety coal pillar25,26,27,28. HF of the roof in the mining face’s recovery roadway, severing the physical and stress transmission link between the roadway roof and the mined-out area. The roof fall at the fractured location gradually stabilizes, forming a supporting structure on one side of the roadway29. HF of the overlying rock layers in the coal seam of the recovery roadway, blocking the impact of dynamic mining pressure on the large haulage roadway and cutting off the high-stress transmission path from the mined-out area to the haulage roadway30. The hydraulic fracturing of coal seam roof can effectively improve the large area of suspended roof in the goaf of working face, thus reducing the high stress environment in the mining area and reducing the vibration and impact caused by mining31,32.

In recent years, many scholars have put forward the method of layered fracturing coal seam roof33,34,35. However, the traditional HF treatment for mining faces with the MTOS is typically carried out by inclined through-layer fracturing boreholes. However, this method is not ideal because the length of the borehole in the target fracturing rock layer is relatively short, resulting in insufficient fracturing of the target rock layer and often failing to achieve the desired fracturing effect. Moreover, it is impossible to achieve precise fracturing of the target layer. Additionally, single-point fracturing methods within the borehole are commonly used for fracturing the rock layers, which leads to low fracturing efficiency and fails to meet the requirements of high recovery intensity mining faces.

Therefore, in this paper, a combined approach of similarity simulation, numerical analysis, and industrial verification was employed to address the issue of large support pressures and significant mining-induced stresses caused by the MTOS at the mining face. This study analyzed the characteristics of the fractured migration of the thick overburden rock and revealed the competitive expansion mechanism of grouped fractures formed in close proximity within the borehole. A layered group fracturing (LGF) technique for MTOS was proposed. The technique had shown good results in field applications, and the findings provided useful references for fracturing in similar thick overburden rock layers.

Project overview

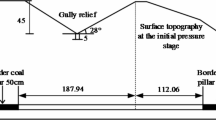

The working face is located in the eastern part of the No. 1 shaft of the mine, covered by sand dunes at the surface. The terrain is gently sloping and relatively flat, with little undulation. The vertical depth from the surface to the working face ranges from 208.4 to 269.1 m, with an average vertical depth of 237.4 m. One wing of the working face is adjacent to an recovered working face, while the other wing consists of unrecovered coal. The ventilation gateway for the lower recovery face has already been established. A safety coal pillar of 40 m is left between each working face. The information of the test working face is shown in Fig. 1.

The overburden of the working face primarily contains 18.1 m of medium sandstone and 52.4 m of coarse sandstone, classifying it as a MTOS. The thickness of the coal seam in the working face is 8.2–9.4 m, with an average thickness of 8.8 m. The dip angle of coal seam is 3°–9°, and the average dip angle is 4°. The working face adopts a single-strike long-wall retreat layout, in which the inclined mining length is 200 m. The comprehensive mechanized top coal caving mining technology is adopted in the working face, the mining height is 3.8 m, and the top coal caving thickness is 5 m. The ZF13000/25/43D top coal caving hydraulic support is selected in the mining section of the mining face, and the maximum support height is 4.3 m. The roof information of the test working face is shown in Table 1.

Due to the presence of this MTOS, the resistance of the support at the working face during excavation of coal is significant, and there is noticeable pressure from the mining area, which severely affects the safe production of the working face. Therefore, a layered group fracturing (LGF) technology of the MTOS is proposed, which could artificially modify the structural characteristics of the MTOS and weaken its strength. The technical principle involves using long-distance horizontal directional drilling technology to create high-level, middle-level, and low-level fracturing boreholes in the target MTOS. Then, grouped fracturing is conducted within these boreholes to achieve rapid and precise layered artificial modification of the MTOS, as schematically shown in Fig. 2.

Fracture migration characteristics in layered fracturing of thick overburden

Construction of physical similar models

The roof breaking and caving characteristics during the mining period of the coal mining face are significantly affected by the boundary effect around the stope. Therefore, a three-dimensional physical similarity model should be established when analyzing the roof breaking characteristics within the whole stope. However, considering that the three-dimensional physical similarity model cannot directly observe the roof breaking characteristics, and the two-dimensional physical similarity model established along the coal seam strike in the middle of the working face can better reflect the roof breaking law of the stope. Therefore, a two-dimensional physical similarity model is established to analyze the roof breaking characteristics of the layered fracturing thick overburden working face.

In addition, in order to achieve the optimal effect of stratified fracturing in the thick rock strata of the stope, the length of the horizontal section of the fracturing fracture in each layer should be maximized. At the same time, taking into account the difficulty of directional fracturing drilling construction in the test face and the thickness of the thick rock strata of the coal seam, the high-level fracturing fracture and the medium-level fracturing fracture are arranged at the third position of the upper thick rock strata, and the low-level fracturing fracture is arranged at the second position of the lower thick rock strata, so as to realize the stratified fracturing of the thick rock strata of the stope. Therefore, the EPS high-density foam board with a thickness of 1 cm is buried at the preset position during the model laying process. Before the first excavation of the model, the EPS high-density foam board was melted by a resistance hot melter with a length of 12 cm and a diameter of 5 mm to simulate layered cracks. The physical similarity model of layered fracturing in thick overburden working face is shown in Fig. 5. The displacement measuring points with a diameter of 20 mm were pasted on the surface of the model according to the row spacing of 100 mm × 100 mm, and the displacement photogrammetry system was used to monitor the displacement data of the coal seam roof during the mining process of the model. The two-dimensional physical similarity simulation is shown in Fig. 3. Similar model experiment material ratio table is shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of failure and collapse in layered fracturing of thick overburden

Figure 4 presents the failure and collapse characteristics of the overburden in the layered fracturing model of the MTOS. When the working face advances to 67.5 m, the immediate roof exhibits maximum bending deformation, but no collapse occurs. However, when the working face reaches 75 m, the immediate roof experiences its first collapse, forming a hinge structure at both ends of the recovery space, with a maximum collapse length of 62.87 m. At 97.5 m, the lower overburden below the low-level fractures experiences its first collapse, creating a larger hinge structure in the direction of the working face’s advancement, while the area above the mined-out space collapses completely, resulting in a cantilever beam structure for the overburden. When the working face reaches 120 m, the upper overburden above the lower rock layer collapses for the first time, forming a masonry beam structure with collapse lengths of 42.93 m and 54.04 m, respectively. At 150 m, the lower overburden below the mid-level fractures collapses for the first time, with the maximum thickness of the collapsed block measuring 25.5 m, adhering to the lower masonry beam and creating a total thickness of 31.25 m for the mid-level masonry beam structure. As the working face advances from 150 to 165 m, the mid-level masonry beam structure provides effective support for the lower recovery space. At this point, the influence of recovery is limited to the immediate roof, with negligible impact on the overburden above the low-level fractures. When the working face reaches 180 m, the lower overburden below the high-level fractures collapses for the first time, forming a larger masonry beam structure, with collapse lengths of 26.41 m and 127.14 m, respectively. Finally, at 200 m, the overburden above the high-level fractures experiences a collapse, but its impact on the working face recovery is negligible. Overall, the layered fracturing of very thick overburden effectively reduces the step distance of collapses at the working face, lowers the pressure from the overburden, and the resulting low-level, mid-level, and high-level masonry beam structures provide substantial support for the recovery space, significantly weakening the mining pressure on the working face.

Migration characteristics of layered fracturing in thick overburden

Figure 5 presents the characteristics of the migration of layered MTOS during different stages of excavating. The results show that: (1) When the working face reaches 70 m, the immediate roof exhibits the maximum bending subsidence, with a maximum subsidence of 4.78 mm; (2) At 75 m, the first collapse occurs in the immediate roof, where the migration curve shows a distinct “concave” shape, and the maximum vertical collapse distance is 61.32 mm. Simultaneously, slight subsidence is observed in the upper overburden area, with a maximum subsidence of 7.12 mm; (3) As excavating progresses, the migration curve of the immediate roof gradually descends in the direction of advancement, maintaining an overall “concave” shape; (4) When the working face reaches 120 m, the lower overburden measurement line(M-L) shows a “V” shape in its descent, with a maximum vertical collapse distance of 62.48 mm; (5) At 150 m, the first coordinated “V” type collapse occurs in the upper overburden 1st and 2nd M-Ls, indicating close contact and synchronized migration of the layers below the mid-level fractures; (6) At 180 m, a coordinated “V” type collapse is observed in 3rd and 4th M-Ls of the upper overburden, suggesting close contact and synchronized migration of the layers below the high-level fractures; (7) When the working face reaches 200 m, the layer above the high-level fractures, represented by 5th M-L, shows a descent with a maximum vertical collapse height of 45.61 mm. In summary, as the working face progresses, the migration curve of the immediate roof presents a “concave” shape, while the migration curves of the lower and upper rock layers display a “V” shape. During the excavating period, the thick overburden experiences two coordinated “V” type collapses, indicating that the layered fracturing of the thick overburden effectively reduces the thickness of the rock layers and mitigates the risk of sudden drops, which could lead to extensive roof pressure impacts. Furthermore, once the “V” shaped masonry beam structure forms from the collapsed blocks of the layered MTOS, the periodic breakage and collapse of the working face roof does not significantly impact the overlying rock layers, demonstrating that the “V” shaped masonry beam structure can effectively support the overburden and greatly reduce the roof pressure intensity at the working face.

Fracture initiation and expansion characteristics in grouped drilling fracturing

Numerical model construction

Using Abaqus numerical analysis software and the extended finite element method, an analysis model for the competitive expansion of group fracturing fissures in the thick overburden of the stope is constructed, and the competitive expansion characteristics of fracturing hydraulic fissures in rock mass under different fracturing spacing conditions are analyzed. The numerical analysis model is based on the physical and mechanical parameters of the thick overburden rock in the test working face. The model size is designed as long × wide = 300 m × 300 m, and a total of 22,500 quadrilateral solid elements are created. According to the previous rock fracture parameters of the test working face, the fracture spacing is selected to be 2 m, 3 m, 4 m and 5 m respectively to construct four numerical models of competitive expansion of group fracture in super thick overburden rock under different fracture spacing conditions, as shown in Fig. 6.

The model is constrained with fixed displacement boundaries on all sides and is subjected to an initial boundary condition of 0 MPa of hydrostatic pressure. The initial stress conditions are set with a horizontal stress of 6 MPa along the x direction and a vertical stress of 8 MPa along the y direction. The model is defined as a linearly elastic porous material, with its physical and mechanical parameters listed in Table 1. Additionally, the initial saturation of the model is set to 1.0, indicating that the model’s pores are completely filled with the fracturing fluid (Table 3).

Characteristics of competitive HFs expansion in group fracturing

Characteristics of HFs competitive expansion paths

Taking the geometric center of the model as the origin of the coordinate axis, the expansion direction and length of each hydraulic fracture during rock mass fracturing are extracted. The Matlab software is used to draw the competitive expansion path of hydraulic fractures with different fracture spacing in borehole group fracturing, as shown in Fig. 7. It can be observed that HFs symmetrically expand from the Y-axis towards both wings at various spacings. Specifically, when the fracturing distances are 2 m and 3 m, the upper and lower HFs expand in opposite directions. However, at fracturing distances of 4 m and 5 m, the upper and lower HFs expand in parallel. This indicates that when the fracturing distance is small, there is a competitive expansion phenomenon between the upper and lower HFs. The tendency for the upper and lower HFs to expand in opposite directions is particularly pronounced at a fracturing distances of 2 m. Conversely, at a fracturing distances of 4 m, the competitive expansion characteristics between the upper and lower HFs are significantly weakened.

Evolution law of HFs extension length during competitive expansion

Figure 8 illusrates the evolution patterns of group HF lengths under different fracturing distances. It can be observed that the competitive expansion of HFs under varying fracturing distances conditions can be divided into two stages: (1) Independent Expansion Stage: During the early stages of fracturing, the expansion range of the upper and lower HFs are relatively small, leading to minimal impact on the surrounding rock. Consequently, the two HFs expand independently, resulting in their expansion length characteristic curves being largely overlapping. (2) Competitive Expansion Stage: As high-pressure water continues to be injected, the expansion range of both HFs within the rock increases. Gradually, competition for expansion emerges between the two HFs, causing their expansion length characteristics to diverge. Moreover, as the fracturing distances increases, the duration of independent expansion for the upper and lower HFs gradually extends, resulting in a delayed onset of competitive expansion between the HFs.

Evolution law of fluid pressure within HFs during competitive expansion

Figure 9 shows the evolution characteristics of fluid pressure within group HFs at different fracturing distances. The accompanying cloud diagrams of rock pore pressure for varying fracturing spacings are shown in Fig. 10. It can be observed that when the fracturing fluid is injected into the HFs, some of it filters and permeates into the rock, increasing the rock’s pore pressure. Meanwhile, the remaining fracturing fluid gradually fills the fractures, causing a rapid rise in fluid pressure within the HFs and leading to their gradual opening. When the fluid pressure within the HFs reaches the rupture strength of the rock, the rock fractures, generating new fractures. The fracturing fluid then enters these new fractures, causing a sharp drop in fluid pressure within the fractures, which stops their expansion. As the injection of fracturing fluid continues, the fluid pressure in the newly created fractures increases again. When this pressure reaches the rock’s rupture strength, the fractures expand once more, resulting in another sharp drop in fluid pressure. This cyclical process of fracture initiation and expansion leads to a generally serrated characteristic of the fluid pressure curve within the fractures. Additionally, as the fracturing distances increases, the fluid stress within the fractures at the first instance of fracture initiation gradually decreases. For instance, at spacings of 3 m, 4 m, 5 m, and 6 m, the fluid stress within the upper HF at the first instance of fracture initiation is 9.53 MPa, 9.48 MPa, 9.31 MPa, and 9.24 MPa, respectively, while for the lower HF, the corresponding values are 9.55 MPa, 9.41 MPa, 9.33 MPa, and 9.17 MPa. Moreover, as the fracturing distances increases, the duration of independent expansion for the upper and lower HFs also increases, indicating that a greater fracturing distances facilitates the initiation and expansion of HFs while reducing the intensity of competitive expansion between them. Furthermore, as high-pressure water is injected, the fracturing fluid penetrates into the rock and gradually connects the upper and lower HFs, resulting in increasing mutual interference between them. This interference primarily manifests as the upper and lower HFs exerting compressive forces on the intermediate rock, causing the fractures to diverge in their expansion. Additionally, as the fracturing distances increases, the rock’s pore pressure gradually decreases, and the extent of the fracturing fluid penetrating the rock diminishes, leading to reduced mutual interference between the upper and lower HFs during their expansion.

Mechanism of HFs competitive fractur expansion in group fracturing

Figure 11 shows the evolution characteristics of the rock stress field under different fracturing durations for group fracturing. Evolution characteristics of the maximum principal stress in rock under different fracturing distances are shown in Fig. 12. It can be observed that the impact range of the fracture initiation and expansion primarily presents an upper and lower symmetric “hourglass” shape. As the fracturing duration increases, the influence range of fracture initiation and expansion gradually expands, and the maximum principal stress within the rock also increases. Figure 11 illustrates the evolution characteristics of the principal stress between the upper and lower hydraulic fractures. It is evident that as the fracturing spacing increases, the onset time for the competitive expansion mechanism between the hydraulic fractures also increases. Specifically, at fracturing spacings of 2 m, 3 m, 4 m, and 5 m, the times for the onset of competitive expansion between the upper and lower hydraulic fractures are 13.26 s, 22.65 s, 33.21 s, and 46.91 s, respectively. Moreover, as the fracturing spacing increases, the degree of impact from competitive expansion between the hydraulic fractures gradually decreases. For spacings of 2 m, 3 m, and 4 m, the maximum principal stresses in the rock between the fractures are 13.15 MPa, 11.81 MPa, and 10.79 MPa, respectively, with corresponding fracturing durations of 23,149 s, 336.85 s, and 498.77 s.

Layered group fracturing of MTOS: engineering practice

Engineering implementation

Based on the aforementioned research, the key parameters for the layered grouped fracturing (LGF) technology of the MTOS at the mining face are shown in Table 2. The LGF technology process of the MTOS consists of two main steps: (1) Directional Drilling: In the next constructed return airway, three long-distance directional drilling rigs are arranged. Simultaneously, long-distance horizontal boreholes are conducted within the MTOS of the mining area, with the drilling direction aligned with the advancement direction of the working face, as illustrated in Fig. 13. (2) Sealing and fracturing : According to the fourth part, based on the physical and mechanical characteristics of the super-thick overburden rock in the test working face, the analysis of the competitive expansion characteristics of the group-cracking cracks was carried out. It was found that when the crack spacing was 4 m, the competitive expansion characteristics of the upper and lower hydraulic cracks were significantly weakened, which was conducive to the long-distance expansion of the hydraulic cracks. Therefore, when the long-distance directional horizontal drilling was completed, the holes were sealed and cracked in groups from the bottom of the hole to the orifice according to the 4 m spacing, as shown in Fig. 14 (Table 4).

Monitoring of injection pressure in HFs

Figure 15 presents the evolution characteristics of the pumping pressure during the LGF of the MTOS. The characteristics of the high-pressure pumping station can be divided into three stages: (a) When high-pressure water is injected into the fractures and quickly fills the fracturing section of the boreholes, the pumping pressure rises rapidly. The maximum pumping pressure during this stage corresponds to the fracture initiation pressure. (b) As high-pressure water continues to be injected, the water pressure within the fractures increases again. When this pressure reaches the rock’s fracture strength, the rock fractures once more, leading to further expansion of the fractures and a rapid decrease in water pressure within them. Consequently, the pumping pressure can partially reflect the state of fracture expansion. (c) When the pumping is artificially stopped or when the fractures encounter natural cracks or other drainage channels, the water pressure within the fractures drops rapidly and does not increase again, indicating that the fractures have entered a unloading phase. As the depth of the fracturing layer increases, the rock’s fracture initiation pressure rises, and the average pumping pressure also increases. Specifically, when fracturing the upper-level, middle-level, and lower-level fractures, the initiation pressures are 20.09 MPa, 22.19 MPa, and 24.92 MPa, respectively, while the corresponding average pumping pressures are 17.24 MPa, 18.95 MPa, and 20.15 MPa.

Comparison of support resistance before and after LGF

Figures 15 and 16 respectively give the evolution law of working resistance of support before and after stratification and group fracturing of thick overburden in stope. The average working resistance of the stope support is reduced from 17.59 KN to 15.85 KN, with a decrease of 9.89%. In addition, the pressure step distance of the stope is significantly reduced, and the average pressure step distance of the stope is reduced from 127.45 m to 41.71 m, with a decrease of 67.27%. Before the fracturing of the thick overburden strata in the stope, the average working resistance difference of the support before and after the weighting of the stope is 9.46 KN, while after the fracturing of the thick overburden strata in the stope, the average working resistance difference of the support before and after the weighting of the stope is 7.28 KN. It shows that the fracturing of the thick overburden strata in the stope changes the roof structure of the coal seam, makes the roof of the working face break in the form of small fracture step, greatly reduces the working resistance of the working face support, and effectively alleviates the impact of the roof fracture pressure on the working face support (Fig. 17).

Conclusion

-

1.

After the LGF technology for MTOS is adopted, the roof of the working face are periodically broken and collapsed with a smaller caving step distance, and the joint fracture occurs between the MTOS. The upper strata of the MTOS is mainly supported by the ' V ' type masonry beam structure formed by the caving rock block in the goaf. At this time, the periodic weighting strength of the working face is mainly affected by the direct roof breaking of the coal seam, which greatly reduces the mining pressure of the stope.

-

2.

The group fracturing technology can multiply improve the efficiency of LGF for MTOS of stope. In the initial stage of grouped fracturing, HFs exhibit free expansion characteristics. As the fracturing duration increases, a “backward” competitive expansion feature gradually emerges between the HFs. When the fracturing distance is small, the onset of competitive expansion occurs sooner and is more intense. The evolution of the stress field within the rock due to fracture expansion is the fundamental reason for the “backward” competitive expansion of the HFs.

-

3.

In the process of LGF technology for MTOS, the expansion pressure of hydraulic fracture in surrounding rock can be divided into three stages: compression, expansion and unloading. In addition, with the increase of buried depth of rock strata, the fluid pressure required for the initiation of surrounding rock increases gradually, and the fluid pressure required for the expansion of hydraulic fractures in rock mass increases gradually. At the same time, the LGF technology for MTOS can effectively reduce the support resistance and periodic weighting step distance of the working face, and then reduce the periodic weighting strength of the working face, so as to provide guarantee for the safe production of the working face.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, H., Liu, K., Tie, S. & Wang, L. Coal consumption and economic growth: A Chinese city-level study. Energy Econ. 109, 105940 (2022).

Wang, J., Feng, L. & Tverberg, G. E. An analysis of China’s coal supply and its impact on China’s future economic growth. Energy Policy 57, 542–551 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. Instability mechanism and control of section coal pillar in fully mechanized mining face with super thick roof and extra thick seam. J. China Coal Soc. 46(12), 3756–3770 (2021).

Bai, X. et al. Mine earthquake mechanism of extremely thick strata based on focal memchanism analysis. J. China Coal Soc. 48(11), 4024–4035 (2023).

Dou, L. et al. Rockburst mechanism caused by the mining-induced drainage of confined water in deep extra-thick aquifer. J. China Coal Soc. 49(1), 351–366 (2024).

Dou, L. et al. Fracturing characteristics of significantly thick overburden inducing mine earthquakes and the stress-triggering mechanisms of the mine earthquakes. Coal Geol. Explor. 52(10), 1–13 (2024).

Warpinski, N. R., Mayerhofer, M. J., Agarwal, K. & Du, J. Hydraulic-fracture geomechanics and microseismic-source mechanisms. SPE J. 18(04), 766–780 (2013).

Veatch, R. W. Overview of current hydraulic fracturing design and treatment technology-Part 1. J. Petrol. Technol. 35(04), 677–687 (1983).

Kreipl, M. P. & Kreipl, A. T. Hydraulic fracturing fluids and their environmental impact: then, today, and tomorrow. Environ. Earth Sci. 76(04), 160 (2017).

Huang, B., Liu, C., Fu, J. & Guan, H. Hydraulic fracturing after water pressure control blasting for increased fracturing. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 48(06), 976–983 (2011).

Al-Bakri, A. & Hefni, M. A review of some nonexplosive alternative methods to conventional rock blasting. Open Geosci. 13(01), 431–442 (2021).

Lu, Y., Ge, Z., Yang, F., Xia, B. & Tang, J. Progress on the hydraulic measures for grid slotting and fracking to enhance coal seam permeability. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27(05), 867–871 (2017).

Wang, K., et al. A numerical investigation of hydraulic fracturing on coal seam permeability based on PFC-COMSOL coupling method. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 09(01) (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Multi-fractured horizontal well for improved coalbed methane production in eastern Ordos basin, China: Field observations and numerical simulations. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 149, 107488 (2020).

Shen, W., Bai, J., Wang, X. & Yu, Y. Response and control technology for entry loaded by mining abutment stress of a thick hard roof. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 90, 26–34 (2016).

Kang, H., Lv, H., Gao, F., Meng, X. & Feng, Y. Understanding mechanisms of destressing mining-induced stresses using hydraulic fracturing. Int. J. Coal Geol. 196, 19–28 (2018).

Kang, H. & Feng, Y. Hydraulic fracturing technology and its applications in strata control in underground coal mines. Coal Sci. Technol. 45(1), 1–9 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Directional permeability evolution in intact and fractured coal subjected to true-triaxial stresses under dry and water-saturated conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 119, 22–34 (2019).

Xia, B., Zhang, X., Yu, B. & Jia, J. Weakening effects of hydraulic fracture in hard roof under the influence of stress arch. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 28(06), 951–958 (2017).

Xia, B., Zhou, Y., Zhang, X., Zhou, L. & Ma, Z. Physical and numerical investigations of target stratum selection for ground hydraulic fracturing of multiple hard roofs. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 34(05), 699–712 (2024).

Zhang, F. et al. Fixed-length roof cutting with vertical hydraulic fracture based on the stress shadow effect: A case study. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 32(02), 295–308 (2022).

Fu, Z., et al. Stress superposition characteristics and roof structure control of recovery room in close distance coal seam. Coal Sci. Technol. 1–15 (2024).

Lin, Z., Li, Y., Wu, J. & Yang, Y. Influence of hydraulic fracturing on the behavior of mine pressure at the end of mining. J. Mining Saf. Eng. 40(04), 714–721 (2023).

Lin, Y., Liu, J., Liu, Y. The influence of key parts of hydraulic roof cutting and roof fracture behavior in mining roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 1–15 (2024).

Liu, J., Liu, C., Yao, Q. & Si, G. The position of hydraulic fracturing to initiate vertical fractures in hard hanging roof for stress relief. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 132, 104328 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Ji, F., Zhao, T., Yang, K., Wu, W., Jiang, W. Theoretical and applied research on hydraulic slit-fracture joint roof control and pressure relief of hard roof in goaf roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 1–13 (2023).

Zhao, S. et al. Mechanism of rockburst prevention for directional hydraulic fracturing in deep-hole roof and effect test with multi-parameter. J. Mining Saf. Eng. 36(06), 1247–1255 (2019).

Huang, B., Liu, J. & Zhang, Q. The reasonable breaking location of overhanging hard roof for directional hydraulic fracturing to control strong strata behaviors of gob-side entry. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 103, 1–11 (2018).

Wang, Q. et al. Geomechanics model test research on automatically formed roadway by roof cutting and pressure releasing. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 135, 104506 (2020).

Huang, B., Shao, L., Zhao, X., Li, H. & Chen, S. Stress transfer to protect mining roadway by roof directional hydraulic fracturing. J. Mining Saf. Eng. 40(05), 991–1002 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. The Formative factors of a rock burst based on energy calculations and the experimental verification of butterfly-shaped plastic zones. Fractal Fract. 7, 829 (2023).

Zhang, W., Ma, N., Ren, J., Li, C. Peak particle velocity of vibration events in underground coal mine and their caused stress increment. Mearsurement 169 (2021).

Xiao, C., Zhang, G. & Yu, Y. Numerical analysis of hydraulic fracturing processes for multi-layered fractured reservoirs. Energy Rep. 7, 467–471 (2021).

Zou, Y. et al. Hydraulic fracture growth in a layered formation based on fracturing experiments and discrete element modeling. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 50, 2381–2395 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Fracture initiation pressure prediction of hydraulic fracturing for layered reservoirs considering borehole deformation. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1334175 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52404147), the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX23_2787) and the Graduate Innovation Program of China University of Mining and Technology (2023WLKXJ026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. conceptualized the study and supervised the project. Y.C. provided funding acquisition. Y.G. wrote the original draft. S.W. conducted the investigation and collected the data. N.H. designed the methodology and data analysis. Y.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Cao, Y., Gou, Y. et al. Mechanism and application of competitive fracture propagation in layered group fracturing of massive thick overburden strata. Sci Rep 15, 9308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91591-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91591-y