Abstract

Predicting vegetation-induced flow resistance remains a significant challenge due to the diverse and dynamic nature of river vegetation. Although numerous empirical models are available, they often fail to generalize across different environmental conditions, leading to inaccurate predictions. This study introduces a machine learning-based framework for predicting vegetation flow resistance, incorporating nine ML methods, including SVM, XGBoost, and BP. To improve predictive performance, optimization algorithms such as PSO, WSO, and RIME were applied. A comprehensive dataset of 490 samples across multiple scales was used to evaluate model accuracy, indicated: (1) The submergence ratio \(\alpha\) and Froude number Fr are the most sensitive parameters affecting Cd, while missing parameters such as vegetation density \(\lambda\) and blockage ratio \(\beta\) significantly reduce accuracy; (2) XGBoost outperforms other models, achieving the highest predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.9552); (3) The framework remains stable across six parameter deficiency scenarios, with XGBoost maintaining R2 > 0.85 in all cases. In conclusion, this study highlights the transformative potential of the proposed predictive framework in overcoming the long-standing challenges of estimating flow resistance in vegetated channels. It provides valuable insights for sustainable river management, bolsters restoration efforts, and enhances predictive accuracy in complex, dynamic environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of river networks is influenced by complex biogeomorphic processes and various contributing factors, with channel evolution primarily driven by abiotic processes, including morphological dynamics and hydrodynamic characteristics1,2. However, recent studies have increasingly emphasized the importance of biological processes, particularly vegetation flow dynamics3,4,5,6,7. Aquatic vegetation plays a key role in habitat protection, sediment transport, and other ecological processes7,8. Vegetation such as reeds, mangroves, and other wetland species have been widely employed in river ecosystem management as nature-based solutions (NBS) for ecological protection. Undoubtedly, quantifying the impact of vegetation on flow resistance is essential for supporting the design of river system management and restoration strategies9. Therefore, a thorough understanding of vegetation-induced resistance is crucial for evaluating the role of aquatic vegetation in ecological engineering10.

Accurately quantifying vegetation-induced resistance remains a formidable challenge11, as it necessitates a deep understanding of how fluid dynamics interact with vegetation structures and influence hydrodynamic processes. Nepf 3 explored how vegetation influences hydrodynamics, particularly how the shape, distribution, and density of vegetation affect fluid flow. Manners et al.12 developed a model to quantify the spatial distribution of vegetation roughness across different scales. However, most studies to date have primarily focused on determining the drag coefficient Cd, which is typically calibrated based on experimental measurements in the lab or field13. Figure 1 presents the cross-sectional flow patterns through submerged vegetation. The contribution of vegetation to overall flow resistance is commonly either neglected, integrated into the total river resistance, or estimated through roughness or friction coefficients14,15.

The parameterization of Cd has been a widely discussed issue in recent research, with many researchers5,16,17,18,19,20 exploring various testing methods and empirical equations to calculate resistance coefficients for vegetation coverage. However, with the limitations of traditional methods in complex natural conditions, recent studies have turned to machine learning (ML) techniques to improve the accuracy and applicability of resistance coefficient predictions for vegetated systems, especially in the fields of water resources management and ecological engineering21,22,23,24. Various prediction methods have provided crucial technical support for the study of vegetation resistance, enabling the development of nonlinear and robust formulas between inputs and outputs without requiring any prior knowledge of underlying phenomena.

Recent studies have applied various ML methods to predict ecological and hydrodynamic variables. For instance, Tian et al.25 used Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) to predict groundwater sulphate content based on 501 samples. Similarly, Deng et al.26 combined Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and SVM with hybrid algorithms to model algae growth and eutrophication over a thirty-year period. Parisouj et al.27 employed Support Vector Regression (SVR), ANN-BP, and Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) for river flow prediction in four rivers. Additionally, Kumar et al.28 explored six ML methods for predicting flow velocity in vegetated alluvial channels29, and later extended their research by using both standalone and hybrid ML techniques to predict flow velocity. Focusing on the resistance coefficient of channels, Roushangar and Shahnazi30 evaluated the sensitivity and robustness of three ML methods, including SVM, to predict Manning’s roughness coefficient in channels with ripple bedforms. Similarly, Mir and Patel24 applied four ML techniques to predict Manning’s roughness coefficient in alluvial channels with bedforms, demonstrating the effectiveness of these approaches in estimating flow resistance. In addition to ML methods, Liu et al.31 utilized genetic programming techniques to predict the drag coefficients of non-submerged vegetation, a method also applied to estimate the drag coefficients of flexible vegetation in wave-driven flows11. These studies provide valuable insights into the complexities of flow-vegetation interactions.

This study utilizes six standalone ML methods and three deep learning (DL) techniques, enhanced by three intelligent optimization algorithms. The performance of these models is compared against three widely used empirical equations to assess their predictive accuracy. The paper is structured as follows: Section "Methods" details the ML and DL approaches employed, along with the optimization algorithms and evaluation metrics. Section "Collected database" provides an overview of the data sources, preprocessing steps, and the dataset design. In Section "Results and discussion", the results are analyzed, focusing on the impact of parameter omission and the application of combined algorithms in flow resistance prediction. Finally, Section "Conclusion" presents the conclusions of the study.

Methods

Dimensional analysis and functional equation

In ML, the functional form representation of physical processes is typically encapsulated by constructing a mathematical model. This can be formalized as \(y = f(x)\), where y denotes the dependent variable, x represents the independent variables, and f signifies the mapping from input to output, embodying the ML model itself. More sophisticated models, such as neural networks, employ a series of layers coupled with nonlinear activation functions to represent, capturing more intricate and nonlinear relationships between inputs and outputs. Similarly, the determination of the vegetation drag coefficient, Cd, can be approached using such methodologies. These data can be directly obtained using pre-configured force measurement setups32,33,34. Drawing upon classical theories of flow around a cylinder, such analyses facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the forces involved.

where \(C_{d}\) represents the drag coefficient for vegetation, \(m\) denotes the quantity of vegetation per unit area, \(d\) is the diameter of the vegetation, \(\rho\) is the density of water, and \(U_{p}\) is the reference flow velocity, typically referring to the pore water velocity within the vegetative flow.

In a flume experiment using cylindrical dowels as a model, Nepf35 discovered that the drag coefficient of vegetation clusters is related to the Reynolds number, Red, and the spacing between the vegetation, \(\Delta S\). Building on this foundation, Stone and Shen36 found that the drag coefficient Cd varies with changes in vegetation Reynolds number, vegetation density, and vegetation diameter. Subsequent researchers analyzed the quantitative relationship between the drag coefficient, vegetation, and flow parameters, proposing a equation to calculate the drag coefficient37.

where a represents the frontal area, \(h_{w}\) denotes the flow depth, \(\lambda\) is the vegetation density, and \(\partial h/\partial x\) represents the energy slope. Consequently, an analysis of the various factors affecting flow resistance can generally be divided into two categories: one is the flow resistance itself, and the other is the resistance introduced by the presence of vegetation, which includes form drag and friction drag.

where \(h_{v}\) represents the height of the vegetation, K denotes the stiffness, \(\mu\) is the dynamic viscosity, Lx is the distance between plants in the direction of the flow, and Ly is the distance between plants in the direction perpendicular to the flow, across the channel width. To further simplify and nondimensionalize Eq. 3, consider the relevant parameters and their dimensional forms.

The third term of Eq. 4 attracts our attention due to \(K \approx \infty\),

The blockage ratio \(\beta\) is often used in fluid dynamics and environmental studies to describe the fraction of the channel that is obstructed by objects such as vegetation and defined as \(\beta = d/L_{y}\). Therefore, we can get the equation for Cd,

where \(\lambda\) is the volume fraction occupied by vegetation, \(\alpha\) is the submersion degree, \(\beta\) is the blockage ratio, Fr is the Froude number, and Rep represents the vegetation Reynolds number.

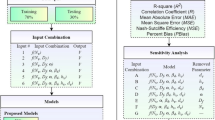

By using ML and DL methods, input–output relationships are established, as shown in Eq. 6. These methods are based on real-world data, with the goal of building a model that captures underlying patterns rather than fitting the data exactly. The model’s framework and key methodologies are illustrated in Fig. 2. This model allows for predicting future responses to new inputs, going beyond replicating observed data to forecast unseen scenarios.

Machine learning algorithms

In this study, the ML and DL models are organized into three distinct groups: non-ensemble ML models (SVM, ELM, RR), ensemble ML models (RF, XGBoost, LSBoost), and DL models (BP, GRN, LSTM). MATLAB was employed for all modeling efforts, ensuring consistency across the nine models by using identical input and output parameters for training.

Non-integrated machine learning models

This research examines the application of three non-ensemble ML models SVM, ELM and Multiple Ridge Regression (RR) in predicting the coefficients of resistance to vegetation water flow. As highlighted by Deng and Liu38, SVM is effective for both classification and regression tasks. Its strength lies in its optimization capabilities through various kernel functions, which allow it to excel in nonlinear problem solving. However, selecting appropriate kernel functions and tuning parameters are crucial to prevent overfitting or underfitting. ELM knowns for its rapid training capabilities, was used in a recent study to predict water levels in the Hei River39. This model is suitable for large datasets and excels by setting hidden layer parameters randomly and determining output weights analytically. RR uses L2 regularization to manage highly correlated variables, preventing overfitting and making it ideal for data with multicollinearity. This model offers reliable predictions, particularly useful in studies of complex hydrodynamic interactions with vegetation.

Integrated machine learning models

In modern ML, RF, introduced by Breiman40, is a prominent ensemble method that uses multiple decision trees to boost prediction accuracy. Each tree is trained on the entire dataset with a unique random vector, enhancing diversity in training and combining predictions through a majority voting mechanism for improved predictive power. RF is effective with large, high-dimensional datasets and is robust against noise and outliers, though it is prone to overfitting in noisy scenarios. Boosting, another powerful ensemble strategy, enhances the accuracy of weak learners through iterative training focused on previously misclassified instances. XGBoost, developed by Chen and Guestrin41 and used in various engineering applications42,43,44, is a gradient boosting model renowned for its speed and efficiency on large datasets. XGBoost excels in managing overfitting and ensuring high predictive accuracy, although its performance is sensitive to parameter settings. LSBoost employs linear models as weak learners within a gradient boosting framework, ideal for datasets with prominent linear relationships. However, its effectiveness decreases with non-linear data complexities, in contrast to methods using decision trees as base learners.

Deep learning algorithm

Backpropagation (BP) is an essential algorithm for training neural networks, widely used to update weights by computing the gradient of the loss function to minimize errors. Often paired with gradient descent, BP efficiently trains complex multilayer feedforward networks, showing robust performance across various applications. The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) simplifies the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture by combining forget and input gates into a single “update gate” and merging the cell state with the hidden state, enhancing learning efficiency for sequence prediction tasks45,46. LSTM networks address long-term dependencies in sequence data, a challenge for traditional RNNs, with gating mechanisms such as input, forget, and output gates. These features make LSTM effective for applications that require understanding relationships over extended periods, such as language modeling and time series analysis.

Optimised learning algorithms

PSO algorithm

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a collective intelligence-based optimization technique introduced by Eberhart and Kennedy47. This algorithm simulates the social behavior of bird flocks, where each “particle” represents a candidate solution in the solution space. Particles adjust their positions and velocities by tracking the best positions found individually and by the group as a whole. The standard form of PSO is,

where \(\omega\) is the inertia factor, \(v_{i}\) is the particle’s velocity, and rand() is a random number between 0 and 1, c1 and c2 are learning factors. PSO is particularly well-suited for dealing with continuous optimization problems and has been widely applied in engineering design, neural network training, and other scientific research fields.

WSO algorithm

Whale Shark Optimization (WSO) is a novel optimization algorithm inspired by the hunting behavior of great white sharks48. The algorithm simulates principles such as the social behavior of sharks, a leader–follower structure, position updating, leaping behavior, and fitness evaluation. Through these mechanisms, the WSO algorithm can effectively search for the optimal or near-optimal solutions within the solution space.

where \(w_{k}^{i}\) and \(w_{k + 1}^{i}\) is the positions of the two best solutions retained, and they are used to update the positions of other sharks in the swarm. R is a random number between 0 and 1.

RIME algorithm

The RIME algorithm49 simulates the growth processes of “soft time” and “hard time” in time-ice modeling to develop a soft time search strategy and a hard time puncturing mechanism. This approach enhances both exploration and exploitation in optimization methods. When tested against ten established algorithms and ten recently improved ones, RIME demonstrated superior performance. The key optimization process involves,

where \(R_{ij}^{{\text{new }}}\) is the new position of the updated particle, \(R_{best,j}\) is the \(j - th\) particle of the best rime-agent in the rime-population, \(r\) is a random number, \(\cos \theta\) is the direction of particle movement, \(\varepsilon\) is the environmental factor, C is the degree of adhesion, E is the coefficient of being attached.

Empirical equations for \(C_{d}\) and model evaluation indicators

Researchers have studied the estimation of vegetation resistance coefficients from various perspectives. We have selected the most widely used calculation equations for this purpose. Cheng and Nguyen50 introduced an empirical best-fit function to characterize the relationship between \(C_{d}\) and \(Re_{v}\), derived from existing experimental data on \(C_{d}\).

where \(Re_{v}\) is the vegetation Reynolds number, which is defined as \(Re_{v} = 0.25\pi \lambda (1 - \lambda )Re_{p}\).

Sonnenwald et al.51 redefined \(\alpha_{0}\) and \(\alpha_{1}\) in terms of \(\lambda\) and \(d\) through least-squares curve fitting using available experimental data, leading to a function for estimating \(C_{d}\).

Kothyari et al.52 developed a \(C_{d}\) prediction model through multi-parameter regression analysis based on their experimental data. The model is expressed as,

To assess and compare the performance of the ML and DL models developed in this study, five key metrics were employed: the mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), index of agreement (IA), determination (R2), and Kling-Gupta Efficiency (KGE)53,54,55.

where \(y_{{{\text{true}},i}}\) is the observed value, \(y_{{{\text{predict}},i}}\) is the predicted value, \(\overline{y}_{{{\text{true}}}}\) is the mean of the true values, \(\overline{y}_{{{\text{pred}}}}\) is the mean of the predicted values, n is the total number of data, R is the correlation coefficient between the observed and predicted values, \(\xi\) is the ratio of the standard deviations of the observed and predicted values, \(\gamma\) is the ratio of the means of the observed and predicted values.

In addition, Tables 1 and 2 provide the datasets collected in this study along with the hyperparameter settings for the ML models used in this study. These include data from 20 research teams, the key models and their optimized values, such as maximum depth, learning rate, and other metrics. These configurations serve as guidelines for setting hyperparameters in prediction tasks.

Collected database

The preprocessing of raw data is a critical step in developing ML models, as it enhances the efficiency and accuracy of predictive operations. This preprocessing involves identifying and handling missing values, eliminating duplicates and outliers, and standardizing the dataset. In this study, outliers are detected based on their deviation from the mean using the Z-score detection method. A higher Z-score indicates a greater deviation from the mean, making it an effective measure for identifying anomalous data points. This method is highly versatile, as it can be applied to various data distributions and is not restricted to normal distributions. The red hollow circles in Fig. 3 highlight the detected outliers.

where x is a sample of the data set, \(\mu\) is the sample mean, and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation.

Detailed data distribution is shown in Table 1.

In order to better understand the distribution characteristics of each parameter and provide valuable information for subsequent modeling and analysis, Fig. 4 presents the frequency distributions of six key parameters, including input parameters \(\lambda\), \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(Re_{p}\), \(F_{r}\) and the output parameter \(C_{d}\). The red curves in the figure represent the fitted distributions, revealing the skewness of each parameter’s distribution. Overall, all the parameters exhibit some degree of skewness, and each parameter has a distinct distribution pattern. Among the input parameters, \(\lambda\) shows a clear skewed distribution, with most of the data concentrated in the lower range, demonstrating a tendency for values to cluster around a small range. In contrast, \(\alpha\) exhibits a more uniform distribution, with the values spread more evenly across the entire range, showing no significant concentration.

Consequently, the data was randomly partitioned into three subsets: the training dataset (60%), the validation dataset (20%), and the test dataset (20%). The random division of the data is clearly illustrated in Fig. 5.

Results and discussion

Exploring inter-feature correlations and distributions

In this study, the relationships between the predictive model parameters were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient to evaluate their interdependence. The coefficient ranges from -1 to 1, where 0 indicates no linear correlation, and -1 or + 1 represents a perfect negative or positive linear relationship, respectively. Five parameters were identified in Section "Dimensional analysis and functional equation", and Fig. 6 illustrates the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix for the input parameters. The analysis revealed no significant pairwise correlations, except between λ and β. Specifically, β, which represents the blockage ratio, exhibits a strong negative correlation with density λ. This finding is expected, as β is inherently linked to the vegetation arrangement pattern, implying a certain degree of collinearity between λ and β.

The boxplots for the six normalized parameters in Fig. 7 reveal distinct distribution patterns. \(\lambda\) and \(C_{d}\) show relatively low variability, indicating that their standardized values are concentrated within a narrow range, suggesting consistency and less fluctuation. On the other hand, \(\alpha\) and \(F_{r}\) exhibit significant variability, with wider interquartile ranges and clear outliers, suggesting these parameters experience more substantial changes or fluctuations. This indicates that \(\alpha\) and \(F_{r}\) may be more sensitive to external factors or experimental conditions. \(Re_{p}\) and \(\beta\), in comparison, show moderate variability, indicating some level of fluctuation but without the extreme variation observed in \(\alpha\) and \(F_{r}\), implying that these parameters tend to be more stable but still exhibit some level of inconsistency across the data.

ML predictive performance evaluation

ML has been widely applied to predict environmental quality in numerous studies; however, its use in estimating the drag coefficient (Cd) remains underexplored. This study employs ML techniques to predict Cd under both submerged and non-submerged vegetation conditions, with performance evaluated using metrics such as MAE, RMSE, IA and KGE across nine ML models (Fig. 8). Among these, XGBoost achieves the lowest MAE of 0.0802. In contrast, models such as SVM, ELM, and RR exhibit greater variability and significant deviations from actual values. This is reflected in their lower R2 values in scatter plots, with SVM, for instance, achieving an R2 of 0.7083, indicating limited predictive power and accuracy. On the other hand, XGBoost and LSBoost display superior performance, with XGBoost achieving the highest R2 of 0.9552, indicating a robust linear relationship between predicted and actual values. While LSTM and GRU demonstrate commendable predictive capabilities, they still fall short compared to XGBoost. Based on these findings, XGBoost is identified as the most effective model for predicting Cd.

XGBoost demonstrates exceptional performance in predicting the drag coefficient Cd, significantly outperforming traditional models such as SVM, ELM, and RR. These traditional models exhibit considerable variability and relatively lower predictive accuracy, with SVM achieving an R2 of 0.7083, as illustrated in Fig. 9. In contrast, XGBoost stands out among ensemble methods, achieving the highest R2 of 0.9552, reflecting a nearly perfect linear relationship between predicted and observed values, as shown in Fig. 10. Although DL models, such as LSTM and GRU (shown in Fig. 11), exhibit satisfactory performance with R2 values exceeding 0.8, they still fall short of the precision and robustness demonstrated by XGBoost. The superior predictive performance of XGBoost can be attributed to its advanced ensemble learning framework, which combines multiple weak learners to improve accuracy, alongside effective regularization techniques that prevent overfitting. These features allow XGBoost to achieve an optimal balance between model complexity and prediction stability. Consequently, XGBoost is particularly well-suited for estimating flow resistance in vegetated channels, as evidenced by its consistent and highly accurate results across all evaluation metrics.

As a comparison, we have included the results from widely used empirical equations for Cd, as shown in Eqs. 10 to 12. To maintain consistency with ML, we compared these equations with the observed values, as depicted in Fig. 12. Notably, the R2 values for the three empirical equations were all below 0.6, highlighting the limitations of these models when applied to larger datasets. This is evident in the line and scatter plots of the predicted versus measured Cd values, where the deviations between the predicted and actual values are substantial. In contrast, the machine learning-based Cd prediction method effectively addresses these issues by learning complex patterns in the data, leading to more accurate and robust predictions across a broader range of datasets. In conclusion, while empirical equations may work for limited datasets or simple cases, they struggle with more complex data. The machine learning-based approach fills this gap, offering improved predictive performance over a wider range of conditions.

Model accuracy analysis based on optimised learning algorithms

Enhancing predictive performance by integrating ML with statistical and optimization methods, this study nominates XGBoost as the model with the best performance due to its robust generalizability and accuracy. Recognizing the necessity to adapt model selection based on distinct usage scenarios, the study employs optimization algorithms, namely PSO, WSO, and RIME optimization algorithm, to refine the predictive accuracy of each evaluated ML model. These enhancements, aimed at aligning the models more closely with specific predictive requirements, are systematically documented in Table 3, illustrating the tailored adjustments and resultant improvements.

The PSO-XGBoost model demonstrated superior performance across all metrics, achieving the lowest MAE of 0.076, RMSE of 0.117, and the R2 value of 0.959. These results highlight the model’s exceptional ability to produce highly accurate predictions, with minimal deviation from observed values. The superior performance of PSO-XGBoost can be attributed to its advanced ensemble learning framework and robust regularization techniques, which allow it to effectively capture complex, nonlinear relationships within the data. In contrast, although models such as SVM, ELM, and RR showed some improvement after optimization, these models’ relatively simplistic architectures limited their capacity to exploit the intricate patterns present in the dataset, resulting in relatively modest performance gains.

While DL models, including LSTM and GRU, demonstrated notable improvements following optimization, they still fell short of XGBoost in terms of predictive accuracy. The RIME-BP model, for instance, achieved a R2 value of 0.948 and a KGE score of 0.946, reflecting the potential of advanced optimization techniques to enhance the performance of both traditional and DL models. Nevertheless, despite these gains, DL models were unable to match the precision and stability exhibited by XGBoost, particularly in terms of MAE and RMSE. This analysis underscores the continued dominance of ensemble methods like XGBoost in handling complex, real-world predictive tasks, particularly in the context of flow resistance estimation in vegetated channels.

Discussion

Model prediction based on missing parameters

To enhance the understanding of variable interdependencies in Cd prediction, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between Cd and various parameters, revealing a spectrum of linear associations. The parameter α exhibited the strongest positive correlation, marked by a coefficient of 0.81, denoting a significant linear relationship. Fr followed with a coefficient of 0.28, indicating a moderate positive correlation. Notably, Rep displayed a negative correlation of -0.20, underscoring an inverse relationship with Cd, while λ had a modest positive correlation of 0.17. The parameter β showed an almost negligible correlation of 0.03, implying minimal linear association with Cd. These results highlight the multifaceted factors affecting the drag coefficient and emphasize the necessity of considering diverse parameters for precise fluid dynamics modeling. Considering the significant correlations with parameters α (indicative of vegetation characteristics) and Fr (reflective of hydraulic conditions), it is imperative to assess the predictive capabilities of our chosen models when one or both of these influential parameters are absent. This examination will illuminate the models’ resilience in the face of incomplete data and delineate the extent to which model efficacy relies on these critical inputs. Detailed scenarios involving missing parameter values and the corresponding impacts on model performance are presented in Table 4.

From the data presented in Fig. 13, it is evident that the correlation coefficients vary between 0.855 to 0.913, demonstrating that XGBoost consistently ensures high predictive accuracy, even in scenarios of missing values. Although λ and β are considered key factors that influence the decline in accuracy, the model’s predictive performance remains closely matched in scenarios where either λ or β is missing. While Rep does not have a significant impact on model performance on its own, the absence of both λ or β simultaneously results in the poorest predictive accuracy.

Simulation algorithms based on different combinations

In this study, the integration of different ML models, including SVM-RF, BP-RF, and LSTM-XGBoost, is investigated to enhance predictive accuracy and performance. This fusion-based approach, as illustrated in Fig. 14, leverages the complementary strengths of individual models, enabling the extraction of intricate data patterns that single models might overlook. By combining the unique capabilities of each model, this strategy aims to improve robustness, minimize prediction errors, and better address the complexities inherent in the underlying data. Such methodological integration is well-established in model fusion theory, offering a promising pathway for enhanced predictive power in complex systems.

The study revealed that combined models also possess strong predictive performance, particularly the LSTM-XGBoost hybrid, which achieved an accuracy of 0.9548. This combination harnesses the LSTM’s strength in capturing dependencies in sequential data along with XGBoost efficiency in handling complex nonlinear patterns. By integrating these approaches, we were able to extract and utilize features within the data more effectively, resulting in a significant performance enhancement in time series prediction tasks. This synergistic approach underscores the potential of model fusion in leveraging the unique advantages of different algorithms to address diverse challenges in data analysis.

Conclusion

This study presents a novel integrated framework for predicting the drag coefficient Cd, evaluating nine different ML and DL models, further enhanced by optimization algorithms PSO, WSO, and RIME to improve predictive accuracy. The results demonstrate that the XGBoost model is the most robust, achieving an R2 value of 0.9552. Notably, traditional ML methods also exhibit significant adaptability when combined with optimization algorithms, with even the least accurate models, such as SVM, showing substantial improvements, achieving R2 values exceeding 0.8 after optimization. In addition to enhancing individual models, the integration of hybrid approaches, particularly the LSTM-XGBoost fusion, highlights the transformative potential of model ensemble techniques in improving the predictive accuracy for complex environmental systems. Another key feature of this framework is its resilience in handling incomplete datasets; even with missing critical parameters (such as \(\beta\), \(\lambda\), and \(Re_{p}\), XGBoost maintains outstanding predictive performance. This study provides an efficient and reliable tool for predicting vegetation-induced flow resistance, advancing the understanding of aquatic vegetation hydrodynamics and offering scientific support for ecological restoration and watershed management. Future research may focus on using DL methods to predict resistance and flow velocity data over longer time scales. Additionally, the hybrid approach demonstrated significant potential for broader applications and could be leveraged to enhance the model’s generalization and performance across different environmental contexts.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Corenblit, D., Tabacchi, E., Steiger, J. & Gurnell, A. M. Reciprocal interactions and adjustments between fluvial landforms and vegetation dynamics in river corridors: a review of complementary approaches. Earth Sci. Rev. 84, 56–86 (2007).

Gurnell, A. M. & Bertoldi, W. Plants and river morphodynamics: The emergence of fluvial biogeomorphology. River Res. Apps 40, 887–942 (2024).

Nepf, H. M. Flow and transport in regions with aquatic vegetation. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 44, 123–142 (2012).

Vargas-Luna, A., Crosato, A. & Uijttewaal, W. S. J. Effects of vegetation on flow and sediment transport: Comparative analyses and validation of predicting models. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 40, 157–176 (2015).

van Rooijen, A., Lowe, R., Ghisalberti, M., Conde-Frias, M. & Tan, L. Predicting current-induced drag in emergent and submerged aquatic vegetation canopies. Front. Mar. Sci. 5, (2018).

Sonnenwald, F., Stovin, V. & Guymer, I. Estimating drag coefficient for arrays of rigid cylinders representing emergent vegetation. J. Hydraul. Res. 57, 591–597 (2019).

Cornacchia, L. et al. Self-organization of river vegetation leads to emergent buffering of river flows and water levels. Proc. R. Soc. B. 287, 20201147 (2020).

Rominger, J. T. (Jeffrey T. Hydrodynamic and transport phenomena at the interface between flow and aquatic vegetation: from the forest to the blade scale. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2014).

Murray, A. B. & Paola, C. Modelling the effect of vegetation on channel pattern in bedload rivers. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 28, 131–143 (2003).

Green, J. C. Modelling flow resistance in vegetated streams: review and development of new theory. Hydrol. Process. 19, 1245–1259 (2005).

Predicting the bulk drag coefficient of flexible vegetation in wave flows based on a genetic programming algorithm. Ocean Eng. 223, 108694 (2021).

Manners, R., Schmidt, J. & Wheaton, J. M. Multiscalar model for the determination of spatially explicit riparian vegetation roughness. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surface 118, 65–83 (2013).

Busari, A. O. & Li, C. W. A hydraulic roughness model for submerged flexible vegetation with uncertainty estimation. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 9, 268–280 (2015).

Petryk, S. & Bosmajian, G. Analysis of flow through vegetation. J. Hydraul. Div. 101, 871–884 (1975).

Neary, V. S., Constantinescu, S. G., Bennett, S. J. & Diplas, P. Effects of vegetation on turbulence, sediment transport, and stream morphology. J. Hydraul. Eng. 138, 765–776 (2012).

Aberle, J. & Järvelä, J. Flow resistance of emergent rigid and flexible floodplain vegetation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 51, 33–45 (2013).

D’Ippolito, A., Calomino, F., Alfonsi, G. & Lauria, A. Flow resistance in open channel due to vegetation at reach scale: A review. Water 13, 116 (2021).

Anjum, N. & Ali, M. Investigation of the flow structures through heterogeneous vegetation of varying patch configurations in an open channel. Environ. Fluid Mech. 22, 1333–1354 (2022).

Ji, U., Järvelä, J., Västilä, K. & Bae, I. Experimentation and modeling of reach-scale vegetative flow resistance due to willow patches. J. Hydraul. Eng. 149, 04023018 (2023).

Shang, H. et al. Effect of varying wheatgrass density on resistance to overland flow. J. Hydrol. 591, 125594 (2020).

Torres, A. F., Walker, W. R. & McKee, M. Forecasting daily potential evapotranspiration using machine learning and limited climatic data. Agric. Water Manag. 98, 553–562 (2011).

King, A. T., Tinoco, R. O. & Cowen, E. A. A k–ε turbulence model based on the scales of vertical shear and stem wakes valid for emergent and submerged vegetated flows. J. Fluid Mech. 701, 1–39 (2012).

Yaseen, Z. M., Sulaiman, S. O., Deo, R. C. & Chau, K.-W. An enhanced extreme learning machine model for river flow forecasting: State-of-the-art, practical applications in water resource engineering area and future research direction. J. Hydrol. 569, 387–408 (2019).

Mir, A. A. & Patel, M. Machine learning approaches for adequate prediction of flow resistance in alluvial channels with bedforms. Water Sci. Technol. 89, 290–318 (2023).

Tian, Y. et al. Prediction of sulfate concentrations in groundwater in areas with complex hydrogeological conditions based on machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 923, 171312 (2024).

Deng, T., Chau, K.-W. & Duan, H.-F. Machine learning based marine water quality prediction for coastal hydro-environment management. J. Environ. Manag. 284, 112051 (2021).

Parisouj, P., Mohebzadeh, H. & Lee, T. Employing machine learning algorithms for streamflow prediction: A case study of four river basins with different climatic zones in the united states. Water Resour. Manage 34, 4113–4131 (2020).

Kumar, S., Kumar, B., Deshpande, V. & Agarwal, M. Predicting flow velocity in a vegetative alluvial channel using standalone and hybrid machine learning techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 232, 120885 (2023).

Kumar, S. et al. AI-driven predictions of geophysical river flows with vegetation. Sci. Rep. 14, 16368 (2024).

Roushangar, K. & Shahnazi, S. Insights into the prediction capability of roughness coefficient in current ripple bedforms under varied hydraulic conditions. J. Hydroinform. 23, 1182–1196 (2021).

Liu, M.-Y., Huai, W.-X., Yang, Z.-H. & Zeng, Y.-H. A genetic programming-based model for drag coefficient of emergent vegetation in open channel flows. Adv. Water Resourc. 140, 103582 (2020).

Ishikawa, Y., Mizuhara, K. & Ashida, S. Effect of density of trees on drag exerted on trees in river channels. J. For. Res. 5, 271–279 (2000).

Kothyari, U. C., Hayashi, K. & Hashimoto, H. Drag coefficient of unsubmerged rigid vegetation stems in open channel flows. J. Hydraul. Res. 47, 691–699 (2009).

Tinoco, R. O. & Cowen, E. A. The direct and indirect measurement of boundary stress and drag on individual and complex arrays of elements. Exp. Fluids 54, 1509 (2013).

Nepf, H. M. Drag, turbulence, and diffusion in flow through emergent vegetation. Water Resourc. Res. 35, 479–489 (1999).

Stone, B. M. & Shen, H. T. Hydraulic resistance of flow in channels with cylindrical roughness. J. Hydraul. Eng. 128, 500–506 (2002).

Stoesser, T., Kim, S. J. & Diplas, P. Turbulent flow through idealized emergent vegetation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 136, 1003–1017 (2010).

Deng, Y. & Liu, Y. Prediction of depth-averaged velocity for flow though submerged vegetation using least squares support vector machine with Bayesian optimization. Water Resour. Manage. 38, 1675–1692 (2024).

Bai, Y. et al. Application of a hybrid model based on secondary decomposition and ELM neural network in water level prediction. J. Hydrol. Eng. 29, 04024002 (2024).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 2016).

Mustapha, I. B., Abdulkareem, Z., Abdulkareem, M. & Ganiyu, A. Predictive modeling of physical and mechanical properties of pervious concrete using XGBoost. Neural Comput. Appl. 36, 9245–9261 (2024).

Sulaiman, B. H., Ibrahim, A. M. & Imran, H. J. Study the efficiency of the XGBoost algorithm for squat RC wall shear strength prediction and parametric analysis. (2024).

Wang, Z. H. et al. Intelligent prediction model of mechanical properties of ultrathin niobium strips based on XGBoost ensemble learning algorithm. Comput. Mater. Sci. 231, 112579 (2024).

Yu, Y., Si, X., Hu, C. & Zhang, J. A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural Comput. 31, 1235–1270 (2019).

Zhang, Y. Utilizing Hybrid LSTM and GRU Models for Urban Hydrological Prediction. (University of Guelph, 2024).

Kennedy, J., & Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. in Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks vol. 4 1942–1948 (IEEE, 1995).

Braik, M., Hammouri, A., Atwan, J., Al-Betar, M. A. & Awadallah, M. A. White shark optimizer: A novel bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 243, 108457 (2022).

Su, H. et al. RIME: A physics-based optimization. Neurocomputing 532, 183–214 (2023).

Cheng, N.-S. & Nguyen, H. T. Hydraulic radius for evaluating resistance induced by simulated emergent vegetation in open-channel flows. J. Hydraul. Eng. 137, 995–1004 (2011).

Sonnenwald, F., Hart, J. R., West, P., Stovin, V. R. & Guymer, I. Transverse and longitudinal mixing in real emergent vegetation at low velocities. Water Resourc. Res. 53, 961–978 (2017).

Kothyari, U. C., Hayashi, K. & Hashimoto, H. Drag coefficient of unsubmerged rigid vegetation stems in open channel flows. J. Hydraul. Res. 47, 691–699 (2009).

Daneshfaraz, R., Norouzi, R., Abbaszadeh, H. & Azamathulla, H. M. Theoretical and experimental analysis of applicability of sill with different widths on the gate discharge coefficients. Water Supply 22, 7767–7781 (2022).

Abbaszadeh, H., Daneshfaraz, R., Sume, V. & Abraham, J. Experimental investigation and application of soft computing models for predicting flow energy loss in arc-shaped constrictions. AQUA Water Infrastruct. Ecosyst. Soc. 73, 637–661 (2024).

Najafzadeh, M. & Mahmoudi-Rad, M. New empirical equations to assess energy efficiency of flow-dissipating vortex dropshaft. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 131, 107759 (2024).

Su Jin Kim & Thorsten Stoesser. Closure modeling and direct simulation of vegetation drag in flow through emergent vegetation. Water Resourc. Res. 47, (2011).

Etminan, V., Lowe, R. J. & Ghisalberti, M. A new model for predicting the drag exerted by vegetation canopies. Water Resourc. Res. 53, 3179–3196 (2017).

James, C. S., Birkhead, A. L., Jordanova, A. A. & O’Sullivan, J. J. Flow resistance of emergent vegetation. J. Hydraul. Res. 42, 390–398 (2004).

Ferreira, R. M., Ricardo, A. M. & Franca, M. J. Discussion of “Laboratory Investigation of Mean Drag in a Random Array of Rigid, Emergent Cylinders” by Yukie Tanino and Heidi M Nepf. J. Hydraul. Eng. 135, 690–693 (2009).

Shimizu, Y., Tsujimoto, T., Nakagawa, H. & Kitamura, T. Experimental study on flow over rigid vegetation simulated by cylinders with equi-spacing. Doboku Gakkai Ronbunshu 1991, 31–40 (1991).

Dunn, C., Lopez, F., & Garcia, M. H. Mean flow and turbulence in a laboratory channel with simulated vegatation (HES 51). Hydraul. Eng. Series no. 51 (1996).

Meijer, D. G., & Van Velzen, E. H. Prototype-scale flume experiments on hydraulic roughness of submerged vegetation. in (Graz, Austria., 1999).

López, F. & García, M. H. Mean flow and turbulence structure of open-channel flow through non-emergent vegetation. J. Hydraul. Eng. 127, 392–402 (2001).

Ghisalberti, M. & Nepf, H. The limited growth of vegetated shear layers. Water Resourc. Res. 40, 7 (2004).

Murphy, E., Ghisalberti, M., & Nepf, H. Model and laboratory study of dispersion in flows with submerged vegetation: Dispersion in flows with submerged vegetation. Water Resour. Res. 43, (2007).

Yan, J. Experimental study of flow resistance and turbulence characteristics of open channel flow with vegetation (Hohai University, 2008).

Yang, W. Experimental study of turbulent open-channel flows with submerged vegetation (Yonsei University Seoul, 2008).

Liu, D., Diplas, P., Fairbanks, J. D. & Hodges, C. C. An experimental study of flow through rigid vegetation. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surface 113, F04015 (2008).

Tang, H., Tian, Z., Yan, J. & Yuan, S. Determining drag coefficients and their application in modelling of turbulent flow with submerged vegetation. Adv. Water Resourc. 69, 134–145 (2014).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFC3211800, 2023YFD1900803), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (8232052), the Bingtuan Science and Technology Program (2023AB060), and the 2115 Talent Development Program of China Agricultural University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.J. and Y.H. conceptualized the study. W.W. and Z.L. conducted the experiments and data collection. Y.Z. and J.D. performed data analysis and interpretation. H.G. prepared the figures and tables. Y.H. and F.J. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, F., Wang, W., Han, Y. et al. Predictive framework of vegetation resistance in channel flow. Sci Rep 15, 7593 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91668-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91668-8