Abstract

The development of efficient parallelization strategies for numerical simulation methods of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics remains one of the key technology challenges in modern scientific computing. The numerical models of gas and plasma dynamics based on the Navier-Stokes and electrodynamics equations require enormous computational efforts. For such cases, the use of parallel and distributed computing proved to be effective. The Grid computing environment could provide virtually unlimited computational resources and data storage, convenient task launch and monitoring tools, graphical user interfaces such as web portals and visualization systems. However, the deployment of traditional CFD solvers in the Grid environment remains very limited because basically it requires the cluster computing architecture. This study explores the applicability of distributed computing and Grid technologies for solving the weak-coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics, including techniques of flow separation control like using plasma actuators to influence boundary layer structure. The adaptation techniques for the algorithms of coupled computational fluid dynamics and electrodynamics problems for distributed computations on grid and cloud infrastructure are presented. A parallel solver suitable for the Grid infrastructure has been developed and the test calculations in the distributed computing environment are performed. The simulation results for partially ionized separated flow behind the circular cylinder are analysed. Discussion includes some performance metrics and parallelization effectiveness estimation. The potential of the Grid infrastructure to provide a powerful and flexible computing environment for fast and efficient solution of weak-coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics has been shown.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a rapidly evolving branch of fluid and gas mechanics that frequently requires extensive computational resources, which may exceed the capacity of a particular research organization1,2. In certain cases the simulation time may increase significantly and surpass reasonable limits3 due to the complexity of computational domain configurations and the need for highly detailed meshes4.

Parallel processing technologies offer a solution to this challenge. The application of OpenMP, MPI, CUDA, and similar technologies is a key strategy for achieving effective parallelization of CFD algorithms5.

The numerical methods for solving the Euler and Navier-Stokes equations lack sufficient natural parallelism and therefore require a strongly-coupled distributed computing architecture for effective implementation. The cluster architectures with high-speed interconnect such as Infiniband or, in the worst case, Gigabit Ethernet are proven suitable for parallel CFD-solvers and have a large number of known successful implementations5,6. At the same time, the deployment of parallel computing in CFD becomes challenging for the architectures where the message-passing time between computational nodes increases significantly and is unable to fit within the required limits.

Known implementations of computational methods of fluid dynamics in the Grid environment are therefore limited to task automation systems7,8, development of frontend interfaces9, intermediate software to create various interfaces and gateways between Grid software and solvers such as OpenFOAM, StarCCM and others10,11.

The situation is quite different for the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics12. The substantial difference in the characteristic times of physical processes in gas and plasma enables the use of splitting methods, thereby reducing the requirements for the data exchange rate between two groups of nodes engaged in gas and plasma simulation.

For coupled problems, where the reverse effect of the gas phase on electrodynamics processes can be neglected13, it is possible to use Grid-technologies to build an efficient computational architecture. This approach offers additional benefits. In addition to its extensive computational resources, the Grid environment could provide virtually unlimited data storage, convenient task launch and monitoring tools, graphical user interfaces such as web portals and visualization systems. The combination of Grid computing power and on-demand desktop based visualization may be an efficient solution for researchers by visualizing large data sets using relatively inexpensive hardware.

The goal of the present paper is to develop an efficient parallelization technique for such a class of weak-coupled problems using one particular case as an example. This research proves the ability of the Grid infrastructure to provide a powerful and flexible computing environment for fast and efficient solution of coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics.

Related works

Finding the relevant parallelization approach to solve specific CFD problem in a distributed environment is not a new topic in general. Many other researchers have focused on this problem recently.

An article by Afzal et al.5 provides a comprehensive state of the art review of important CFD areas and parallelization strategies for the related software. The use of various parallelization techniques and tools is discussed. Benefits and issues of the different hybrid environments such as Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP), Message Passing Interface (MPI) and Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) are considered. Open areas of CFD where parallelization is not much attempted are identified and parallel computing tools which can be useful for parallel execution of CFD software are highlighted.

One of the first successful attempts to perform the complex CFD simulations in the Grid environment was presented by Wendler and Schintke14. The overall system architecture and some special system features along with the typical CFD job execution are considered. The adoption of Grid tools for monitoring the preliminary results during the runtime is discussed.

The solution and analysis of complex CFD applications using the Grid computing infrastructure is discussed in9. Efficiency of parallel computations is evaluated by performing a benchmark and simulating the dam break flows. The suitability of Grid infrastructure to provide powerful and flexible computing environment for fast and efficient solution of challenging CFD applications has been shown.

The detailed performance analysis of parallel implementations of OpenFOAM, Alya and CHORUS CFD solvers is presented in15. The generic performance metrics helping the code developer to identify the critical points that can potentially limit the scalability of a parallel application are discussed. Recommendations for improving the performance of each application in scalable parallel environment are suggested.

The hybrid parallelization model based on MPI and pthreads for running a turbomachinery CFD code is developed by Simmendinger and Kügeler16. The data exchange between subdomains involved in parallel computations is performed with MPI, whereas the loop parallelization is done using phtreads. The proposed parallelization scheme reduces the communication overhead and therefore increases the parallel code efficiency for manycore architectures.

Another hybrid parallelization approach using MPI and OpenMP technologies is presented in the research papers of Jin et al.17, Shang18, Selvam and Hoffmann19. OpenMP is used for efficient fine-grain parallel computing, while MPI performs the data communication between the domain partitions in coarse-grain parallelization. The advantages of approach proposed to increase the finite-element and finite-difference solvers scalability are shown.

Giovannini et al.20 proposed even more sophisticated hybrid parallelization strategy based on MPI, nested OpenMP parallelism, and SIMD vectorization for turbomachinery applications. The performance of developed code is discussed for the pure MPI, pure OpenMP, and hybrid OpenMP-MPI implementations.

Wang et al.21 suggested the extended MPI-OpenMP parallelization strategies optimized for both homogeneous and heterogeneous CPU clusters. The paper focused on balancing the work load among all kinds of computing cores, tuning the multi-thread code toward better performance for the nodes with hundreds of CPU cores, and optimizing the communication between nodes, cores, and between CPUs and Xeon Phi numerical co-processors.

The hybrid MPI-CUDA parallel programming model for simulation of supersonic turbulent flow over a flat plate on the clusters with GPU equipped computing nodes is proposed in22. Optimization methods to achieve the highest degree of parallelism utilization and maximum memory throughput for effective CPU-GPU communication are discussed.

Advanced parallelization techniques for simulation of the electromagnetic waves propagation in the plasma media are presented in the paper23 by Xiong et al. The computation performance and efficiency comparison of CUDA-based GPU parallel solver and Open MP-based CPU parallel solver are discussed.

A parallel dual-grid multiscale approach using the CFD coupled with Discrete Element Method for particles is developed by Pozetti et al.24. The suggested parallelization strategy provides more flexibility in the domain partitioning while keeping a low inter-process communication cost. The methodology extended for the massively parallel 3D simulations of gas-fluidized bed in complex geometry on unstructured meshes is presented in the study25 by Dufresne et al. Performance scalability tests up to 4144 cores have been conducted.

The coupling of fine-mesh CFD thermal-hydraulics code and neutron transport is considered in the paper26 using the Ansys Fluent User Defined Functions for code development. Different meshing and mapping scenarios are investigated to obtain the optimal scheme that guarantees the physical conservation and provides the required accuracy and efficiency of the parallel solver.

The parallel solvers application for fusion plasma dynamics, particularly for scrape-off layer transport is presented in27. The solver scalability for different scrape-off layer configurations is discussed. It is shown that the computational gains obtained may also be further improved by combining the two coarse solvers along with additional levels of parallelism, such as space parallelization.

Authors of research by Kissami et al.28 focused on hybrid parallelization approach to simulate non-equilibrium ionization processes in 2D streamer flows. For parallel computation of the linear equations system the Intel MKL library29 and UMFPACK30 solvers are used. The parallel solver scalability on homogeneous cluster architecture with up to 1024 computing cores is discussed.

A parallel relativistic three-dimensional particle-in-cell code for the simulation of electromagnetic fields, relativistic particle beams, and plasmas is presented in31. The algorithms used, capabilities, parallelization strategy, and performance results are described. Typical application scenarios of developed code are discussed.

An implicit unstructured grid density-based solver based on a parallel version of the lower upper symmetric Gauss-Seidel (LUSGS) method is developed by Nived and Eswaran32 to compute large-scale engineering problems. A four-layered parallel algorithm is developed to efficiently compute three-dimensional turbulent flows on massively parallel computational hardware. Multiple layers of parallelism including continuity of flow solution, transfer of solution gradients, and calculation of drag-lift-solution residuals, right up to the innermost implicit LUSGS solver sub-routine, which is relatively less explored in the literature, are utilized. The near-linear scalability of the solver developed on supercomputing facility up to 6144 cores is achieved.

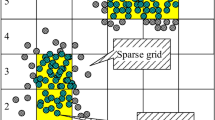

Authors of the paper33 focused on efficient implementation of sparse grid particle-in-cell methods for kinetic plasma simulation on the modern general purpose GPU architectures.

Despite variety of approaches and recent significant progress finding the optimal strategy for parallel implementation of solvers for coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics remains still challenging and requires further research efforts.

Mathematical model for solving coupled problems of computational fluid dynamics and low-temperature plasma dynamics

The boundary layer structure control techniques are highly important for the development of new aviation, rocket and space technologies, design and manufacturing of engines and turbines, as well as wind power plants. Existing methods for controlling flow separation are usually energy-intensive and may require changes to the vehicle design, such as cooling, surface perforation, installation of interceptors or additional moving elements. The formation of a partially ionized flow using plasma actuators is one of the promising techniques of flow structure control. The mathematical model of this process could be considered as a class of the above-mentioned weak-coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics.

In the present research a methodology for solving such a class of problems using the Grid infrastructure is proposed. A solver for the distributed computing environment has been developed and the test calculations of the flow around the circular cylinder with activated plasma actuators have been performed.

Conservation laws for the viscous incompressible flows

The numerical simulation was performed based on unsteady Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations for the viscous incompressible gas using the Boussinesq representation of the turbulent stress tensor and considering the Lorentz forces produced by plasma actuators12. The conservative form of the governing equations34 is given by

where t is time, \({\mathbf{u}}\) is velocity vector, p is the pressure, \(\rho\) is the density, \(\nu\) and \({\nu _t}\) are molecular and turbulent kinematic viscosity coefficients, \({{\mathbf{f}}_b}\) is a vector of mass forces, normalized by the unit volume.

The parameters of the undisturbed flow in the entire computational domain were set as initial conditions. On the solid body surface, no-slip condition is used. The pressure is obtained by specifying a zero pressure gradient normal to the wall. For outer region the non-reflective boundary conditions based on the method of characteristics were used.

Turbulence modeling. In this work, the Spalart-Allmaras (SA) differential turbulence model35 was used for the turbulence simulation.

The standard Spalart-Allmaras turbulence model determines the dimensional kinematic turbulent viscosity coefficient as follows

where \({f_{v1}}={{{\chi ^3}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\chi ^3}} {\left( {{\chi ^3}+c_{{v1}}^{3}} \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {{\chi ^3}+c_{{v1}}^{3}} \right)}}\) is the damping function of kinematic viscosities \(\chi ={{{{\tilde {\nu }}_t}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{{\tilde {\nu }}_t}} \nu }} \right. \kern-0pt} \nu }\), \({\tilde {\nu }_t}\) is working variable.

The equation determining \({\tilde {\nu }_t}\) in Spalart–Allmaras turbulence model is given by

The turbulent viscosity in the incoming flow, calculated based on the intensity of the flow turbulence was used as initial condition in the turbulence models.

The turbulent viscosity value on the body surface was assumed to be zero. The Neumann boundary conditions were applied at the exit boundary. The boundary condition for the value of the turbulent viscosity in the free stream was set as follows36

where Re is Reynolds number.

Kinetic scheme of plasma dielectric barrier discharge

Air with a fixed fraction of nitrogen and oxygen at constant values of atmospheric pressure, density and temperature is considered as an ambient gas. A dielectric barrier discharge in air at atmospheric pressure generates a low-temperature non-equilibrium plasma37,38.

The present study addresses electronically excited and metastable states (*) of nitrogen molecules \(N_{2}^{*}\left( {{A^3}\sum _{u}^{+}} \right)\), \(N_{2}^{{}} \left( {B^{3} \Pi _{g}^{{}} } \right)\), \(N_{2}^{*} \left( {a^{{\prime 1}} \sum _{u}^{ - } } \right)\), \(N_{2}^{{}} \left( {C^{3} \Pi _{u} } \right)\) and oxygen molecules \(O_{2}^{*}\left( {{a^1}{\Delta _g}} \right)\), \(O_{2}^{*}\left( {{b^1}\sum _{g}^{+}} \right)\), neutral oxygen atoms O, electrons e, and positive \(N_{2}^{+}\), \(N_{4}^{+}\), \(O_{2}^{+}\), \(O_{4}^{+}\) and negative ions \({O^ - }\), \(O_{2}^{ - }\). A total of 14 particles and 97 plasma reactions, including surface processes are taken into consideration13,37,38.

Chemical reactions under consideration include: processes of dissociation, ionization of molecules by electron impact; stepwise, associative ionization and photoionization; excitation of molecules; ionization of excited metastable molecules; electron attachment and detachment; recombination of electrons and positive ions; chemical transformations of neutral atoms, molecules and ions, as well as processes of secondary electron emission from exposed electrode and dielectric surface. The temperature of ions was assumed to be equal to the temperature of air. The electron temperature depends on the electric field strength and was determined by solving the Boltzmann equation.

The equation of electric potential

Gauss’s law, taking into account the surface charge, becomes the following form39

where φ is electrical potential, \(\delta \left( h \right)\) is Dirac’s delta function, h is a distance normal to the dielectric surface, \({\rho _c}\) is the density of resulting charge, \(\sigma\) is total surface density of electric charge, \({\varepsilon _r}\) is relative dielectric permittivity of the medium, \({\varepsilon _o}\) is vacuum permittivity. The density of the resulting charge at any point in the plasma is defined as the difference between the densities of the positive and negative charges. Hence the Eq. (6) could be written as follows

where \({n_{{\rm N}_{4}^{+}}}\), \({n_{{\rm N}_{2}^{+}}}\), \({n_{{\rm O}_{4}^{+}}}\), \({n_{{\rm O}_{2}^{+}}}\), \({n_{{\rm O}_{2}^{ - }}}\), \({n_{{\rm O}_{{}}^{ - }}}\), \({n_e}\) are volumetric densities of electrons, as well as positive and negative ions of nitrogen and oxygen, \({\sigma _+}\), \({\sigma _ - }\) are surface densities of positive and negative charges.

Under non-stationary boundary conditions for the potential φ and within presence of time-varying source terms, Eq. (7) may describe unsteady processes in electric field.

The equation of dynamics of plasma particles in the drift-diffusion approximation

Based on the kinetic scheme of the dielectric barrier discharge, the dynamics equations for each type of particle could be derived. The system of equations for the dynamics of plasma particles in the drift-diffusion approximation, taking into account the fact that \({\mathbf{E}}= - \nabla \varphi\), in two-dimensional Cartesian form could be expressed as

where \({\mathbf{n}}\) is the vector of volumetric density of the charged particles, \({\mathbf{\mu }}\) and \({\mathbf{D}}\) are vector coefficients of particle mobility and diffusion, \({\mathbf{S}}\) is the vector of source terms,

In Eq. (8) the product of \({\mathbf{\mu n}}\) means the vector of \({\left[ {{\mu _1}{n_1},\;{\mu _2}{n_2},\;…\;,\;{\mu _\ell }{n_\ell }} \right]^T}\).

Surface density equations for positive and negative charges

Processes on the dielectric surface play an essential role in the operation of plasma actuators. The equations of surface density for positive and negative charges are given by expressions

where \({\Gamma _{i+}}\), \({\Gamma _{i - }}\), \({\Gamma _e}\) are the flows of positive and negative ions and electrons normal to the surface, \({\alpha _{rw}}\) is the surface recombination rate, \({\gamma _{diel}}=0.005\) is the ion-induced secondary electron emission coefficient.

Initial and boundary conditions for the system of plasma dynamics and electric potential equations

Equation (6) for the electric potential was solved using the applied voltage to the electrodes as a boundary condition, as well as the corresponding values of the relative permittivity for air and dielectric. The alternating voltage applied to the exposed electrode may be sinusoidal, rectangular, triangular, or more complex shapes. A zero potential was applied to the insulated electrode. The Neumann condition was applied to the outer boundaries.

The background concentrations of ions and electrons in the air were set as initial conditions for the equation of dynamics of charged plasma particles. Boundary conditions for the equations of dynamics of charged particles on solid surfaces are given in the Table 1.

where \(V_{{i,e}}^{{th}}\) is the thermal velocity of particle motion,, \({\gamma _{Cu}}\) is the coefficient of ion-electron emission from the copper anode, which depends on the electric field strength. The Neumann condition \(\partial n/\partial {\ell _n}=0\) was applied to the outer boundaries. The thermal velocity of the particles was determined by the expression

where \({m_{i,e}}\), \({T_{i,e}}\) are mass and temperature of ions or electrons.

Photoionization modeling

The phenomenon of photoionization has to be taken into account when simulating the dielectric barrier discharge in air to correctly describe the positive streamer. To simulate photoionization, the SP3 Larsen model based on the solution of the Helmholtz differential equations was used.

Adaptation of the basic algorithms of computational fluid dynamics and electrodynamics for distributed calculations on grid and cloud infrastructure

One of the most important stages in the development of a parallel solver is the planning of calculations40. At this stage, the whole computational process is divided by sub-processes which should be distributed across cluster nodes. The main criterion for choosing the distribution of subtasks—the efficient use of processors with minimal time spent on data exchange.

The strategy of process distribution is usually a sort of compromise between the loading balance of all the processors in the cluster and minimizing the communication time spent on sending messages. The usual approach in such cases is one CPU core per one sub-process scheme40,41. This scheme is useful in solving stationary problems, because the post-processing of the solution occurs after completion of the iterative procedure, i.e. after the end of the calculations in all sub-processes.

In the case of non-stationary problems, the situation changes due to significant increase of interim information and exchange operations. For non-stationary problems, a scheme with master scheduler process is used, where the master process is executed on a separate host computer CPU and occupies the highest level in the process hierarchy. The master process does not participate in the calculations directly, but performs the functions of managing all workflows and provides acquiring and processing information from sub-processes. The calculation routines are performed by worker processes, which interact with their neighboring processes and the master process as well.

Additional parallelization possibilities are revealed for the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics. Due to the significant difference in characteristic times of physical processes in the gas and in the plasma, it is possible to use splitting methods and therefore reduce the requirements for the speed of data exchange between groups of nodes involved in the calculations of individual physical environments. The general principle of the parallel calculations scheme proposed by the authors for solving the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics based on the grid and cloud infrastructure is presented on Fig. 1.

Because aerodynamic processes do not affect chemical kinetics and electrodynamics interactions, numerical simulation of plasma electrodynamics and fluid dynamics can be performed on different clusters or grid sites. The simulation results of electrodynamics of plasma in the form of the Lorentz force tensor values are uploaded into the cloud storage.

Uploaded results form a hierarchical data sets corresponding to a predefined control algorithm for plasma actuators, or a database in more sophisticated setups. The cluster performing fluid dynamics simulation retrieves the Lorentz force distribution data for a specific time point from the cloud storage when necessary. This approach made possible to simulate unsteady processes of plasma actuators influence on the fluid dynamics and heat and mass transfer.

A more detailed scheme of proposed information exchange between computational blocks and software components is shown on Fig. 2.

Due to the fact that the computation grids used for calculations of plasma electrodynamics and fluid mechanics may not be identical in the general case, the Lorentz force tensor is imported using either an initialization module or a special block inside the computational cycle with the possibility of distribution of imported data between the workers.

Schemas of parallel algorithms for solving coupled problems of plasma electrodynamics and computational fluid dynamics can be represented as three main blocks: the pre-processor block, the solver block and the post-processing block (Fig. 3).

The initial block is the pre-processor, which consists of three modules, such as task initialization module, performing the initialization and self-identification of each process in a hierarchical system of processes, preparation of job data, i.e. reading data from files; area decomposition module, performing the formation of data structures for each workflow; and the data distribution module for dispensing split data across the worker nodes. The master process is responsible for the implementation of this block.

The solver block is performed by each worker process and consists of computing module, an iterative exchange module and an interim post-processing module.

The post-processor block consists of two modules: the module for collecting calculated data, and the module for final processing the results of calculations. This block is periodically executed by the master process during the calculation, and on the final stage of the algorithm.

It is worth noting that the general design of the parallel solver is similar enough to the sequential one40, however, adding elements of parallel processing, as well as using the strategy of “master-worker” calculations allows to build efficient algorithms for solving coupled problems of CFD and plasma dynamics based on distributed computational architectures.

The efficiency of the computations crucially depends on the middleware used and its quality. Actually, MPI is the most widespread and most mature technology for the development of parallel code on cluster architectures40,42.

The main way of processes interaction in the MPI environment is sending messages to each other using communication procedures calls. The process here is any instance of executed program running on any node of the cluster. Each process is independent of the others and works in its own address space. In most cases, each processor core runs a separate process.

MPI technology allows creating MIMD type parallel programs, which means the interaction of simultaneously running processes with different executable code. However, SIMD (single instruction - multiple data) type of parallelization, which executes the same code on all parallel machines, to process different pieces of data, is more widespread for CFD and plasma dynamics.

Computation load balancing criteria for weakly-coupled architecture consisting of different performance nodes

While solving systems of partial differential equations on a heterogeneous computer cluster, it is necessary to take into account the performance of each computing node15. The performance variation and subsequent load imbalance among worker nodes may occur due to hardware variability, software or hardware configuration issues. Disregarding the difference of processing performances and distributing the same amount of processing data across the worker nodes, causes the faster computing nodes to be always idle some time until synchronization.

Let us consider an ideal computing cluster that can provide performance of P flops, consisting of nodes with different performance—\({P_1},\,{P_2},\, \ldots {P_n}\) flops. Hence, the performance of an ideal cluster could be defined as the sum of the performance of its computing nodes

where m is the number of computing nodes.

Define the relative performance of each computing node, referred to the total performance of the cluster

The sum of the relative productivity of all nodes of an ideal cluster is equal to one

Consider the computational mesh with N nodes. In the case of a homogeneous cluster, with the same performance of computing nodes, the number of grid nodes n per computing node is

In the case of heterogeneous cluster nodes, the number of mesh nodes per computing node must be determined separately. The number of mesh nodes intended for processing by each of the computing node will be determined according to its relative performance (16) in the following form

The distribution of mesh nodes by cluster computing nodes using Eq. (19) allows balancing the computational workload. The number of mesh nodes per computing node determines the total number of arithmetic operations required to obtain a new value of the function, according to the discrete analogue of the original PDE system and the chosen method of solving systems of linear algebraic equations. Therefore, the iterations on each computing node of the cluster will take about the same time and idle time until the data synchronization will be minimized. Such approach may be used in various dynamic or static load balancing scenarios at the cluster node level.

Test simulation results and Estimation of parallelization efficiency

Simulation of the flow around circular cylinder during the operation of plasma actuators

In present study a numerical simulation of airflow around the circular cylinder with outer diameter of D = 100 mm, equipped with two pairs of plasma actuators, positioned as shown on Fig. 4, at Reynolds number Re = 30,000 was carried out.

The simulation was performed using the parallel solver developed. All initial data, as well as boundary conditions were taken from12,43. For the flow structure visualization the contour plots of vorticity magnitude were used.

Schema of the cylinder with four plasma actuators43 (1—cylinder, 2—open electrode, 3—insulated electrode, 4—inner insulator, 5—plasma area).

The distributions of electric potential in the computational domain with activated plasma actuators revealed the maximal values of resulting spatial charge density, observed in the areas with the maximal electric field strength, as shown on Fig. 5.

On the initial stage, the flow development was computed with the plasma actuators turned off. The regular turbulent flow around the cylinder is featured by the presence of von Karman vortex street (Fig. 6a,b). Vortexes, detaching from the cylinder body, remain rotating one by one in opposite directions and form the vortex street in the wake. Activation of the plasma actuators placed on the cylinder surface at ± 90°, ± 135° will result in suppression of von Karman vortex street and the flow around the cylinder become reattached one (Fig. 6c,d).

The suppression of vortex shedding leads to an almost complete restoration of the bottom pressure and, as the result, to a significant decrease of the drag force. The change of the drag coefficient of the circular cylinder within a time is shown on Fig. 7. Turning the plasma actuators on causes a steep reduction of the drag force. Depending on performance of plasma actuators and the flow regime identified by the Reynolds number and the value of drag coefficient may decrease from 2 to 10 times.

The obtained results of the numerical simulation are well correlated with the experimental data43 and simulation results obtained with the unparalleled solver12 as well.

Analysis of data exchange efficiency for the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics

While the efficiency of parallel algorithms for solving PDEs describing individual physical environments is highly dependent from network latency and throughput5,40, the efficiency of parallel solution of a coupled problem weakly depends on the speed of the data transmission channel between different Grid-nodes or clusters, due to the relatively small amount of data to exchange.

For the simulations of the flow around circular cylinder while operating the plasma actuators, the block structured mesh consisted of 536,144 nodes for the plasma electrodynamics code and 784,386 nodes for the CFD code was used. The execution time on the Intel i5 2.8 GHz clusters using Gigabit Ethernet interconnect for both plasma electrodynamics and CFD solvers is shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

The number of MPI processes is ranged from 1 to 32. The time spent on parallel code execution decreases significantly with increasing number of processes, as presented on Fig. 8, which demonstrates the good scalability of the solver. Up to 70–79% of computing resources are spent on solution of the system of linear equations (GMRES). The calculation of the drift components takes approximately 13–17% of the total job execution time, diffusion components—8–12%, respectively.

It was technologically more difficult to estimate the time spent on the individual components of the fluid dynamics solver. Thus, Table 3 shows only the total execution time of the parallel CFD code. The number of MPI processes ranged from 1 to 32 as well.

The parallel fluid dynamics solver demonstrates a fairly good scalability as well (Fig. 9). Execution time is reduced from 39 days for a single-threaded version to less than 2 days for 32 processes.

As can be seen from the data in Tables 2 and 3, the total speedup of the CFD solver follows a more linear pattern in comparison to the plasma electrodynamics solver.

The efficiency of parallelization somewhat degrades with increasing number of processes, and with more than 8 processes noticeable differs from initial linear law (Fig. 10). However, using of 32 worker processes for both the plasma electrodynamics and CFD solvers is expedient and gives a decent performance increase.

The efficiency of parallelization for the considered class of coupled problems almost does not depend on the speed of the data transmission channel between computation clusters. Amount of data to be transferred from the electrodynamics part of the calculation to the CFD part is relatively small. For the test calculations performed in this study, using the mesh of 536,144 nodes for electrodynamics simulation, the data set of the three components of the Lorentz force is approximately 13 MB large. Considering that the calculation, even in the case of 32 involved workers, took more than 36 h, the transfer time of an array of 13 MB even at low Internet speed (< 10 Mbps) is quite small and has neglectable effect on the overall calculation efficiency. Thus, the basic schemes of parallel calculations for the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics presented on Figs. 1 and 2 may be implemented on almost any of the available grid and cloud resources44,45.

Conclusions and recommendations

The authors’ experience in mathematical modeling of the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics allows us to formulate the following recommendations:

-

1.

To obtain sufficient efficiency of distributed computing for the tasks of computational aerohydromechanics and electrodynamics of plasma, it is necessary to use clusters with fast interconnect: minimum − 1000 Mbps Gigabit Ethernet, preferably − 10 Gigabit Ethernet or InfiniBand.

-

2.

To facilitate the decomposition of the computational domain and achieve load balance, it is desirable that the clusters consist of homogeneous computational nodes. Otherwise an appropriate load balancing scenario should apply.

-

3.

High-quality calculated grid and high-quality decomposition of the region help to minimize computational problems when solving the problem.

-

4.

The efficiency of parallelization of the considered class of the coupled problems almost does not depend on the throughput of the network channel between clusters. From the test calculations performed in this study, it follows that the amount of data to be transferred from the electrodynamics calculation unit to the liquid and gas mechanics unit is relatively small. Hence, transferring a few megabytes of data every few hours has a negligible impact on overall computational efficiency. Therefore, the basic schema of parallel calculatFig. (Fig. 1) for the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics could be implemented on almost any of the available grid and cloud resources44.

-

5.

When implementing more complex plasma actuators control scenarios than those presented in test simulation results section, it is necessary to coordinate the computation time of the plasma electrodynamics solver on the allocated cluster resources with the actuator control algorithm to avoid additional downtime of the CFD solver.

Data availability

All data generated in the current study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Responding to the Call: Aviation Plan for American Leadership. Congressionally requested report produced under the auspices of the National Institute of Aerospace, Hampton VA. (2005).

Fletcher, C. Computational Techniques for Fluid Dynamics 1: Fundamental and General Techniques, vol. 401 (Springer, 2012).

Slotnick, J. et al. CFD Vision 2030 Study: A Path to Revolutionary Computational Aerosciences, NASA CR-2014-218178, Langley Research Center, 2060/20140003093 (2014).

Redchyts, D., Gourjii, A., Moiseienko, S. & Bilousova, T. Aerodynamics of the turbulent flow around a multi-element airfoil in cruse configuration and in takeoff and landing configuration. Eastern-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 5 (101), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.15587/1729-4061.2019.174259 (2019).

Afzal, A., Ansari, Z., Faizabadi, A. & Ramis, M. Parallelization strategies for computational fluid dynamics software: state of the Art review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. No. 24, 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-016-9165-4 (2016).

Basermann, H. P. et al. HICFD: Highly efficient implementation of CFD codes for HPC many-core architectures. In Proceedings of an International Conference on Competence in High Performance Computing 1–13 (Springer, 2010).

Roy, D. & Kumar. Computational fluid dynamics in GARUDA grid environment. arXiv: Computational Physics, July 7, 2011. https://arxiv.org/abs/1107.1321

Zinchenko, S. & Kodak. On development of portable distributed computation system middleware. In Proceedings of International Conference Parallel and Distributed Computing SystemsPDCS Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2013 (2013).

Kačeniauskas Solution and analysis of CFD applications by using grid infrastructure. Inform. Technol. Control. 39 (4), 284–290 (2010).

Kissami. High Performance Computational Fluid Dynamics on Clusters and Clouds: the ADAPT Experience, Doctoral Dissertation, Université Paris 13 (2017).

Katsaros, G., Kyriazis, D., Dolkas, K. & Varvarigou, T. CFD automatic optimization in grid environments. In Proceeding of 3rd International Conference From Scientific Computing to Computational Engineering (3rd IC-SCCE), Athens, Greece (2008).

Redchyts, E., Shkvar, S. & Moiseienko. Control of karman vortex street by using plasma actuators. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 15(5), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2019.08266 (2019).

Redchyts, S. & Moiseienko Numerical simulation of unsteady flows of cold plasma during plasma actuator operation. Space Sci. Technol. No. 27 (1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.15407/knit2021.01.085 (2021).

Wendler, F. & Schintke Executing and observing CFD applications on the grid. Future Generation Comput. Syst., pp. 11–18. (2005).

Garcia-Gasulla, M. et al. A generic performance analysis technique applied to different CFD methods for HPC. Int. J. Comput. Fluid Dyn. 34 (7–8), 508–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/10618562.2020.1778168 (2020).

Simmendinger, E. & Kugeler. Hybrid parallelization of a turbomachinery CFD code: performance enhancements on multicore architectures. In Proceedings of the V European conference on computational fluid dynamics ECCOMAS CFD, Lisbon, Portugal 1–15 (2010).

Jin, H. et al. High performance computing using MPI and openmp on multi-core parallel systems. Parallel Comput. 37 (9), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parco.2011.02.002 (2011).

Shang, Z. High performance computing for flood simulation using telemac based on hybrid MPI/OpenMP parallel programming. Int. J. Model. Simul. Sci. Comput. 5 (04). https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793962314720015 (2014).

Selvam, M. & Hoffmann, K. MPI/Open-MP hybridization of higher order WENO scheme for the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations. AIAA Infotech @ Aerosp. 2015, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2015-1951 (2015).

Giovannini, M., Marconcini, M., Arnone, A. & Dominguez, A. A hybrid parallelization strategy of a CFD code for turbomachinery applications. In 11th European Conference on Turbomachinery Fluid Dynamics and Thermodynamics (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Performance optimizations for scalable CFD applications on hybrid CPU + MIC heterogeneous computing system with millions of cores. Comput. Fluids. 173, 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2018.03.005 (2018).

Lai, H., Yu, Z., Tian, H. & Li. Hybrid MPI and CUDA parallelization for CFD applications on multi-GPU HPC clusters. Sci. Program. Article ID 8862123. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8862123 (2020).

Xiong, X., Wang, S., Liu, Z., Peng, S. & Zhong. The electromagnetic waves propagation in unmagnetized plasma media using parallelized finite-difference time-domain method. Optik. 166, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.03.136 (2018).

Pozzetti, G., Jasak, H., Besseron, X., Rousset, A. & Peters, B. A parallel dual-grid multiscale approach to CFD–DEM couplings. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 708–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2018.11.030 (2019).

Dufresne, Y., Moureau, V., Lartigue, G. & Simonin, O. A massively parallel CFD/DEM approach for reactive gas-solid flows in complex geometries using unstructured meshes. Comput. Fluids. 198 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2019.104402 (2020).

Chen, G. et al. Analysis of the performances of the CFD schemes used for coupling computation. Nuclear Eng. Technol. 53 (7), 2162–2173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.01.006 (2021).

Samaddar, D. et al. Temporal parallelization of edge plasma simulations using the parareal algorithm and the SOLPS code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 221, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2017.07.012 (2017).

Kissami, C., Cérin, F., Benkhaldoun, G. & Scarella towards parallel CFD computation for the ADAPT framework. In Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing, ICA3PP 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49583-5_28 (Springer, 2016).

Vecil, J. et al. A parallel deterministic solver for the Schrodinger-Poisson-Boltzmann system in ultra-short DG-MOSFETS: comparison with Monte-Carlo. Comput. Math. Appl. 67 (9), 1703–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2014.02.021 (2014).

Davis, T. Algorithm 832: UMFPACK V4.3—an unsymmetric-pattern multifrontal method. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 30 (2), 196–199. https://doi.org/10.1145/992200.992206 (2004).

Yu, P., Kumar, S., Yuan, A., Cheng, R. & Samulyak SPACE: 3D parallel solvers for Vlasov-Maxwell and Vlasov-Poisson equations for relativistic plasmas with atomic transformations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 277 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2022.108396 (2022).

Nived, V. & Eswaran. A massively parallel implicit 3D unstructured grid solver for computing turbulent flows on latest distributed memory computational architectures. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 182 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpdc.2023.104750 (2023).

Deluzet, G., Fubiani, L., Garrigues, C., Guillet, J. & Narski Efficient parallelization for 3D-3V sparse grid Particle-In-Cell: single GPU architectures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 289 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2023.108755 (2023).

Rogers, S. & Kwak, D. An upwind differencing scheme for the incompressible Navier-Stokes equations. J. Numer. Math. 8, 43–64 (1991).

Spalart, P. & Allmaras, S. A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flow. AIAA Paper (1992). N 439.

Spalart, P. & Rumsey, C. Effective inflow conditions for turbulence models in aerodynamic calculations. NASA Langley Res. Cent. Reprint N 20070035069. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20070035069 (2013).

Capitelli, J. & Bardsley. Nonequilibrium Processes in Partially Ionized Gases, vol. 695 (Plenum, 1990).

Kossyi, A., Matveyev, A. & Silakov, V. Kinetic scheme of the non-equilibrium discharge in nitrogen-oxygen mixtures. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 1 (Nо. 3), 207–220 (1992).

Castellanos. Electrohydrodynamics, 363 (Springer, 1998).

Knight Parallel Computing in Computational Fluid Dynamics (AGARD-CP-578, 1996).

Papetti, S. & Succi An Introduction To Parallel Computational Fluid Dynamics (Nova, 1996).

MPI: A Message-Passing Interface Standard. Message Passing InterfaceForum—Version 3.1. https://www.mpi-forum.org/docs/ (2015)

Thomas, A., Kozlov, T. & Corke Plasma actuators for cylinder flow control and noise reduction. AIAA J. 46 (8), 1921–1931 (2008).

EGI - European Grid Initiative. URL: https://www.egi.eu/.

European Open Science Cloud—EU Node. https://open-science-cloud.ec.europa.eu/.

Funding

U.F.-G. was supported by the government of the Basque Country with the financial support of the ELKARTEK24/78 KK-2024/00117 and ELKARTEK24/26 KK-2024/00069 research programs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Z.: Writing—original draft, software, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. U.F.-G.: Funding acquisition, methodology, investigation, data curation, conceptualization. D.R.: Writing—original draft, validation, supervision, project administration, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. O.G.: Writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, visualization, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. T.B.: Writing—review and editing, writing original draft, visualization, validation, supervision, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zinchenko, A., Fernandez-Gamiz, U., Redchyts, D. et al. An efficient parallelization technique for the coupled problems of fluid, gas and plasma mechanics in the grid environment. Sci Rep 15, 8629 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91695-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91695-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The study of abrasive water jet side cutting process using the coupled FEM-SPH method

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)