Abstract

The increasing occurrence of geological hazards along roadway infrastructures presents a significant concern. Evaluating geological hazard susceptibility along roads is a critical aspect of geological disaster emergency response and rescue efforts. Accurate evaluation outcomes are essential as they play a crucial role in mitigating potential financial losses. However, previous studies on geological hazard susceptibility treated all samples as independent entities, overlooking their spatial interactions. This study introduces a novel geological hazard susceptibility assessment model termed the multi-kernel density information (MKDI) method. The MKDI method integrates information value with kernel density estimation, effectively capturing the spatial dependencies among samples. Furthermore, distinct bandwidths are prescribed for various scales of disasters to facilitate multi-kernel density estimation for geological hazards. The integration of the information method enables the development of a comprehensive geological hazard susceptibility map, capturing the spatial complexities of geological hazard distribution. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, the study area selected for investigation was the G219 National Highway within Zayu County. Various factors were considered for geological hazard susceptibility mapping, including slope, aspect, profile and plan curvature, river and road linear densities, peak ground acceleration, seismic response spectrum characteristics, lithology, elevation, rainfall, and landform. The results show that the MKDI model outperformed previous methods, achieving an AUC value of 0.99. The derived susceptibility map is expected to offer a scientific basis for urban planning, construction, and geological hazard risk management in the study area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As global climate change accelerates and human activities intensify, geological hazards have become more severe and widespread1,2. Geological hazards are among the most significant threats to human society and the environment3,4. Debris flows and collapses are prevalent geological hazards in southwestern China, known for their suddenness and unpredictability, posing substantial challenges to social and economic development5. Activities like highway construction and tunnel blasting during social and economic development disrupt slope stability, increasing the likelihood of debris flows and collapses triggered by rainfall or earthquakes6,7. In this context, evaluating the susceptibility of geological hazards along road corridors is crucial.

The susceptibility assessment of geological hazards is a key component of hazard assessment and is a complex task influenced by various factors8,9,10. Debris flows and collapses result from the combined effects of various environmental factors under triggering conditions11. Currently, methods used for the susceptibility assessment of debris flows and collapses include the Analytic Hierarchy Process, the Information method, and machine learning methods12. Liu et al. compared geological hazard evaluation systems using grid units and slope units in Yuanyang County, China, under various rainfall conditions, concluding that slope units produced more accurate and consistent results (higher AUC values) than grid units, offering better alignment with actual geological hazard surveys13. Chen et al. evaluated landslide susceptibility in Wenchuan County using I-AHP and FCNN models, with FCNN (AUC = 0.910) outperforming I-AHP (AUC = 0.768), identifying lithology, topographic relief, and road proximity as key factors, and providing insights for post-earthquake hazard monitoring and prevention14. Li et al developed a landslide susceptibility map for collector roads in Pingshan County, Hebei Province, using a combination weighting method integrating AHP, CRITIC, and game theory, validated with field investigations, providing a reliable tool to reduce infrastructure vulnerability to landslides15. Ruan et al. assessed landslide susceptibility in the Tuoding section of the Jinsha River using a combination of information content modeling, AHP, and GIS, achieving high accuracy and identifying significant impacts from river and road density, providing a scientific basis for local disaster prevention16. Barman and Das conducted landslide susceptibility mapping in Aizawl district, India, using frequency ratio (FR) and analytical hierarchy process (AHP) methods, identifying distance to roads as the most significant factor and selecting the mean-standard deviation classification (MSC) as the optimal approach, offering valuable insights for hazard management17. Zhang et al. proposed an enhanced landslide susceptibility evaluation method combining AHP and an AdaBoost-optimized random forest (ADB_RF) model, achieving high accuracy (AUC = 96.1%) in Chuxiong Prefecture, Yunnan, and identifying the northwestern region as highly prone to future landslides, providing critical insights for disaster prevention18. Zhang et al. conducted a landslide susceptibility study in Sichuan Province using multi-model coupling methods, with IV-LR achieving the highest accuracy (AUC = 0.848), and generated a susceptibility map highlighting high-risk zones in the eastern and southeastern regions, providing valuable insights for large-scale landslide prevention19. Aziz et al. conducted a comprehensive study on road cut slope stability in Jammu and Kashmir, using kinematic analysis and various geological techniques to assess slope failure mechanisms and produce a landslide susceptibility map, offering mitigation strategies for high-risk areas20. Sayyad et al. developed a waterway erosion sensitivity map for the upper Tajan River watershed using an integrated entropy-information value (IOE-IV) model, identifying key environmental, geomorphological, and physical factors influencing erosion, and providing a rapid and accurate statistical method for erosion management and sustainable development21. Liu et al. proposed an optimized landslide susceptibility evaluation method combining the information value model with machine learning (IV-ML) in the Dabie Mountain area, demonstrating that IV-ML models (e.g., IV-RF, IV-SVM, IV-ANN) significantly outperform traditional machine learning models in prediction accuracy and reliability22. He et al. reviewed the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in landslide risk assessment, highlighting its effectiveness in detection, susceptibility assessment, and displacement prediction, with machine learning models like CNNs and RNNs showing superior performance, while addressing challenges and opportunities for future research23. Qiu et al. developed an interpretable landslide susceptibility model for Zhenba County, China, using Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) optimized via Random Search (RS), with the RF model achieving high accuracy (AUC = 0.965), identifying NDVI and proximity to roads as key factors, and providing insights into landslide mechanisms and prevention strategies24. However, despite the advancements in geological hazard assessment methods, significant research gaps remain. Many existing models focus on specific geological hazard types in isolation, neglecting the interconnectedness between different hazards such as debris flows, collapses, and landslides. This limited scope prevents a comprehensive understanding of hazard behavior under complex conditions. Additionally, while several studies have utilized GIS-based models and machine learning methods, few have integrated real-time monitoring data or dynamic factors, such as rainfall patterns, seismic activities, and ongoing construction activities, which could significantly improve hazard prediction accuracy.

In geological hazard assessment, evaluating hazards along road corridors is particularly important25. National highways span hundreds to thousands of kilometers, traversing diverse terrain types and encountering complex geological conditions, leading to frequent geological hazards during construction and operation and causing significant economic losses. Liu et al. created a geological hazard susceptibility map for the Karakoram Highway, using logistic regression to predict hazard risks such as landslides and debris flows, and providing crucial insights for geohazard management and road safety26. Ali et al. conducted landslide susceptibility mapping for the Karakoram Highway, using GIS, AHP, and WOL methods to analyze factors like active faults, seismicity, and slope angle, producing a map that helps highway authorities manage and mitigate landslide risks27. Mahmood et al. assessed rockfall susceptibility along the M-2 Motorway in Pakistan’s Salt Range, using GIS and various geological, meteorological, and topographical factors to create a susceptibility map, providing insights for risk reduction measures and future highway planning28. Kulsoom et al. assessed landslide susceptibility along the Karakoram Highway using machine learning models, with XGBoost achieving the best performance, validated by SBAS-InSAR deformation analysis, providing an enhanced landslide susceptibility map to guide disaster mitigation and highway management29. Zhou et al. proposed a feature fusion transformer (FFTR) combined with machine learning classifiers for landslide susceptibility mapping along the Karakoram Highway, achieving the best performance with FFTR-RF (AUC = 94%) and incorporating PSInSAR displacement velocity to enhance model comprehensiveness, providing a robust tool for disaster mitigation30. Abdullah et al. analyzed the seismic vulnerability of Delhi metro tunnels, using geostatic, eigenvalue, and nonlinear time history analyses to assess the impact of material properties, tunnel lining, and overburden depth on structural integrity, offering valuable insights for seismic resilience and hazard mitigation31. Wang et al. examined the impact of buffer distance selection on geological hazard susceptibility assessment using RF and FR-RF models, finding that a 1000 m buffer distance achieved the highest accuracy, with RF outperforming FR-RF, and identifying road proximity, river distance, and NDVI as key factors, offering insights for effective hazard management32. Wang et al. developed a coherence-based multi-master-image stacking InSAR workflow to monitor expressway stability in Shanxi Province, China, identifying deformation rate, annual precipitation, bedrock hardness, stream proximity, and traffic load as key factors influencing geohazards, with deformation rate being the most significant, highlighting the need for a comprehensive evaluation beyond InSAR for accurate geohazard assessment33. However, many studies focus on individual hazards, but few integrate multiple hazards that could occur simultaneously along road corridors. These interactions between various hazards are often not fully considered, despite their importance for comprehensive risk management.

However, the density of geological hazards has a certain influence on the degree of regional vulnerability, and some scholars have carried out research on the density of geological hazards. Han et al. proposed a KDE-MDBN model for post-earthquake landslide susceptibility assessment, integrating KDE for spatial effect analysis, singularity index for sample selection, and geodetector for factor weighting, achieving accurate spatial hazard predictions and providing valuable insights for future assessments34. Shu et al. analyzed the spatial distribution and influencing factors of potential geological disaster spots (PGDSs) in Meigu County, Southwest China, using ANN, SDE, KDE, and OLS regression, revealing significant clustering in areas with specific elevation, rainfall, and vegetation conditions, and identifying slope, aspect, population density, and rainfall as key factors for disaster preparedness35.

As of 2021, along the G219 National Highway in Shaya County, a total of 85 geological hazards have been identified, primarily consisting of debris flows and collapses, followed by landslides. Among these, there are 45 instances of debris flows, 31 collapses, and 9 landslides. One of these hazards is classified as large-scale, 28 as medium-scale, and 56 as small-scale.

Among the 45 debris flow hazard sites, 7 are considered relatively stable in current conditions, and 38 are stable. As for the development trend, 27 are classified as relatively stable and 18 as stable. Among the 31 collapse hazard sites, 26 are considered unstable in current conditions, while 5 are relatively stable. In terms of development trend, 27 are classified as unstable and 4 as relatively stable. Among the 9 landslide hazard sites, 5 are relatively stable in current conditions, 3 are stable, and 1 is unstable. Regarding development trend, 1 is unstable and 8 are relatively stable.

The geological hazard situation along the G219 National Highway in Shaya County is severe, highlighting the importance of conducting susceptibility assessments for route selection and geological hazard prevention. This paper selects 12 evaluation factors including slope, aspect, profile curvature, planar curvature, watercourse density, road density, landform, DEM, peak ground acceleration, seismic response spectrum characteristics, lithology, and rainfall. The traditional information method is coupled with kernel density estimation to improve the susceptibility assessment. Kernel density estimation allows for quantitative analysis of spatial clustering of geological hazards. Based on the improved information value calculation formula incorporating kernel density estimation, the susceptibility assessment of geological hazards in the study area is conducted, providing a scientific basis for regional planning, construction, and disaster prevention and mitigation management.

Study area

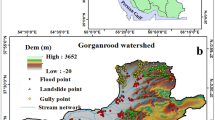

Zayu County spans longitudes 95°45’E to 98°50’E and latitudes 27°45’N to 29°30’N, covering approximately 250 km from east to west and 180 km from north to south. Located in southeastern Tibet Autonomous Region, Zayu County borders Deqin County of the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Gongshan Dulong and Nu Autonomous County, and Zuogong County of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province to the east; Medog County to the west; Myanmar and India to the south; and Bomi County and Basu County of Chamdo City to the north. Zayu County covers an area of 31,530 km2, with terrain sloping from northwest to southeast, featuring higher elevations in the northwest and lower elevations in the southeast. This results in a 3,600 m relative height difference and prominent vertical relief with hanging valleys. The region features typical high mountain canyons and valley landforms. The lowest elevation is 1,400 m at the southern edge of the valley, and more than 10 peaks exceed 5,000 m, with the highest being the 6,740 m Meili Snow Mountain. Two major highways, G559 and G219, pass through Zayu County at an average elevation of 2,300 m The G219 highway extends 505 km within Zayu County, reaching its highest point at 4,706 m above sea level at Yixiula Pass and its lowest point at 1,433 m at the confluence of the Zayu and Sangqu Rivers. Figure 1 provides an overview of the study area.

The primary geological hazards along the G219 National Highway in Zayu County are debris flows, collapses, and landslides, primarily concentrated in Upper Zayu, Lower Zayu, Zhuwagen, and Chawalong Township. The terrain along the G219 highway in Zayu County features diverse landscapes, including glaciers, snow-capped mountains, steep and rugged canyons, and dense tropical rainforests. The region’s climate is influenced by the southwestern monsoon from the Indian Ocean, warm and humid air currents from the Bay of Bengal, and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau high-pressure system, affecting both the Zayu and Nujiang river systems. The area is marked by active faults and tectonic development. The exposed strata in the study area include the Quaternary, Cretaceous, Triassic, Carboniferous, Jurassic, Devonian, and Ordovician periods. The Quaternary deposits, primarily found in ecological protection areas, consist of interbedded quartzite with calcareous mica schist, sericite schist, phyllite, black mica schist, iron-aluminum garnet schist, talc schist, mica marble, and quartzite. Figure 2 illustrates the development of geological hazards in the study area.

The identification of these hazard sites was carried out using a combination of remote sensing data, field surveys, and historical records of geological events. Specifically: Remote Sensing Data: High-resolution satellite images and aerial photographs were analyzed to detect visible signs of geological hazards, such as landslides, debris flows, and collapses. These images were supplemented with topographic maps to identify regions with high susceptibility to hazards. Field Surveys: A series of field investigations were conducted to verify and classify the hazard sites identified from remote sensing data. During these surveys, the geographical coordinates and key characteristics of each site, including the type of hazard (e.g., landslides or debris flows), were recorded. Historical Records: In addition to field surveys and remote sensing, historical data from geological hazard reports and government agencies were reviewed. This allowed us to identify sites that had experienced past hazards, ensuring that we included areas with known susceptibility.

The geological disaster of the field investigation is shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a shows a geological disaster of a medium-sized rock collapse, 220 m wide, 62 m long, 1.8 m thick and 2.46 × 104m3 in volume. Figure 3b shows a landslide geological hazard. The top elevation of the slope where the landslide is located is 3821 m, the foot elevation is 3030 m, and the relative elevation difference is 779 m. Aspect 58°, slope 34°, is a soil slope. The landslide is about 339 m long, 401 m wide, and 6 m thick on average. The landslide volume is 81.56 × 104m3, which is a medium-sized soil pushing landslide. Figure 3c shows a geological disaster of debris flow. The debris flow gully is located on the right bank of the main river. The gully mouth fan is 120 m long and 450 m wide, and the one-time outflow volume is about 1.1 × 104m3.

These identified sites were then classified into different categories based on their type, size, and severity, and were used to assess the overall susceptibility to geological hazards in the study area. There are 85 geological hazard sites along the G219 National Highway in Zayu County, comprising 9 landslides (7 small, 1 medium, 1 large), 31 collapses (14 small, 17 medium), and 45 debris flows (7 small, 1 medium, 1 large). Shaya County consists of five terrain types: low mountain, mid mountain, high mountain, glacier, and mountain canyon landscapes. Geological hazards along the G219 highway primarily occur in mountain canyons and mid-mountain areas, with 59 sites (69.41%) in mountain canyons and 26 sites (30.59%) in mid-mountain areas.

Over 95% of geological hazards in the area occur between June and September. Rainfall in the region is intense, short in duration, and varies significantly across locations. Steep slopes along the Nu and Zayu Rivers cause rapid changes in riverbed gradients, creating conditions for debris flows during prolonged or heavy rainfall. Rainfall significantly influences landslides. Groundwater in slope soil and rock is primarily replenished by atmospheric precipitation. Rainwater infiltrating soil pores or rock fissures triggers repeated freezing–thawing cycles in shallow fissures, causing expansion and reducing the shear strength of rock and soil. Rainfall infiltration softens accumulated slope materials, while elevated groundwater levels increase dynamic and static water pressure, further reducing shear strength and destabilizing slopes. Landslides in the area primarily occur during the summer flood season, underscoring the role of rainfall as a key trigger. While rainfall appears to have a less evident triggering effect on collapses, these events occur year-round in steep sections along the G219 highway, not confined to the rainy season. However, rainfall may still play a role as a trigger. The formation of weak structural surfaces in collapses is closely linked to long-term erosion, scouring, and reduced rock integrity and strength caused by groundwater pressure. Heavy rainfall can accelerate these processes.

Materials

Evaluation units

Defining evaluation units is a fundamental step in geological disaster susceptibility assessments. Currently, grid-based, administrative, slope-based, geomorphic, and other methods are commonly used for this delineation. This study investigates the G219 National Highway corridor in Zayu County. There are also differences in the grid size requirements for different scales, and the grid size is determined according to the following empirical formula:

where \(G_{S}\) is the appropriate mesh size and \(S\) the denominator of the topographic map digital scale.

For 1∶50,000 scale topographic map, the optimal grid cell size calculated from the above formula is 32.8525 m. Considering the specific patterns of geological disaster development along the highway, computational capabilities, and assessment precision, a grid-based approach using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is adopted, with a grid size of 30 m × 30 m. The geological disaster susceptibility along the G219 National Highway in Zayu County is then evaluated. Zayu County covers an area of 3.153 × 104 km2, consisting of 10,220 rows and 7,065 columns, totaling 5,493,763 grid units. In this study, 6,041,788 grid units are identified along the G219 National Highway in Zayu County, with the highway serving as the focal point and a buffer radius of 7,000 m.

Geological hazards conditioning factors

Geological hazards involve significant uncertainty and are shaped by multiple factors. Comprehensive assessment of both susceptibility and the similarities and differences among its contributing factors is essential. Selecting a set of interrelated indicators is crucial for comprehensive analysis. A well-structured evaluation system is essential to ensure rational and objective susceptibility zoning. Selecting appropriate evaluation factors is pivotal to the evaluation process. This study conducted a preliminary assessment of geological hazard susceptibility in Zayu County, based on a comprehensive analysis of the developmental characteristics of geological hazards and their influencing factors. The assessment utilized twelve evaluation factors: slope, aspect, profile curvature, planar curvature, watercourse density, road density, landform, DEM, peak ground acceleration, seismic response spectrum characteristics, engineering geological lithology, and rainfall. Slope, aspect, profile curvature, and planar curvature are calculated from 30 m spatial resolution DEM data obtained from ASTER-GDEM-V2. Linear density of river and Linear density of road are generated from vector network and vector river data. Peak Ground Acceleration and Seismic Response Spectrum Characteristics obtained from the Seismological Bureau. Lithology and landform are derived from field research. Rainfall is derived from spatial interpolation of statistical data from rainfall stations. Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of evaluation factors.

(1) Slope: Slope is a key topographical indicator that significantly influences the occurrence of hazards in the study area. The gravitational stress acting on rock and soil masses along a slope increases proportionally with the slope angle. When the slope angle exceeds the natural angle of repose of surface loose materials, they slide down the slope under the force of gravity. This process continues until the slope angle decreases below the angle of repose, restoring stability. The slope distribution in the study area ranges from 0° to 90° and is categorized into six levels in ArcGIS: [0°–10°), [10°–20°), [20°–30°), [30°–40°), [40°–50°), and [50°–90°].

(2) Aspect: Aspect influences variations in surface illumination, precipitation, temperature, and other environmental factors, which affect vegetation growth and indirectly shape the ecological environment. In the study area, aspect ranges from 0° to 360° and is divided into four levels with 90° intervals: [0°–90°), [90°–180°), [180°–270°), and [270°–360°].

(3) Profile Curvature: Profile curvature influences the flow velocity of slope surface runoff, which in turn affects erosion and deposition processes. It also reflects the stress distribution and the evolutionary history of the slope. Stable erosion reference surfaces over extended periods tend to develop concave or planar slopes. In contrast, intense crustal uplift favors the formation of convex slopes, which are typically less stable. The profile curvature in the study area ranges from 0 to 58 and is categorized into six levels in ArcGIS: [0–5), [5–10), [10–15), [15–20), [20–30), and [30–58].

(4) Plan Curvature: Plan curvature refers to the curvature of terrain in the horizontal direction. In digital elevation models (DEMs), it represents the tangential curvature of the terrain surface on a plane. Higher plan curvature values indicate more pronounced curvature changes in the horizontal direction and steeper terrain morphology. In ArcGIS, plan curvature is categorized into seven levels: [0°–10°), [10°–20°), [20°–30°), [30°–40°), [40°–50°), [50°–60°), and [60°–80°].

(5) Linear density of river: Zayu County is characterized by abundant precipitation, dense vegetation, a warm and humid climate, and extensive glacier and snow cover. The region contains over 1,300 perennial rivers, including 28 major rivers, all part of the Indian Ocean drainage system. A linear density analysis of the watercourses in Zayu County was conducted using ArcGIS. The range of river density is [0–1.39].

(6) Linear density of road: Engineering activities such as slope excavation for road construction and channeling often serve as triggering factors for frequent geological disasters in the area. Due to topographic constraints, roads are generally constructed along riverbanks, resulting in numerous high and steep slopes and dangerous rock formations without slope protection measures. Additionally, most irrigation channels constructed by slope cutting use dry stone masonry without waterproofing treatment, leading to increased groundwater levels, larger saturated areas, and reduced shear strength of rock and soil masses, exacerbating slope deformation. Using ArcGIS, a line density analysis of roads in Zayu County was performed. The range of road density is [0–7.21].

(7) Peak Ground Acceleration (PGA): PGA is an indicator of seismic dynamics that measures the maximum acceleration generated by seismic waves at the Earth’s surface. It is commonly used in seismic susceptibility assessments to quantify the intensity of seismic activity and reflect the severity of earthquake motion. Higher PGA values indicate a greater likelihood of severe geological disasters. In Zayu County, most PGA values are 0.15 g, with some areas along the western edge reaching 0.20 g.

(8) Seismic Response Spectrum Characteristics: The seismic response spectrum is a graphical tool used to describe the dynamic response of structures to earthquakes. It plots the vibration period of a structure on the horizontal axis and the corresponding acceleration response on the vertical axis. This spectrum provides insights into how structures respond to seismic activity at various vibration periods, which indirectly relates to geological hazard susceptibility. In Zayu County, the characteristic seismic response period is predominantly 0.45 s, while in areas near the southeastern border with Yunnan Province, it decreases to 0.40 s.

(9) Lithology: Different types of engineering geological lithologies influence the formation of geological hazards to varying degrees. In Zayu County, lithologies are classified into five groups based on their impact on geological hazards:

1.Hard blocky granite and diorite lithology: This lithology is generally resistant to weathering, characterized by its dense and compact structure. While it provides a stable foundation for construction, its resistance to weathering can result in steep slopes that are prone to instability under certain conditions, such as after heavy rainfall. The occurrence of landslides and collapses is possible, especially in areas where weathering or cracking of these hard rocks has occurred over time.

2.Soft-hard interbedded sandstone, slate, and mudstone lithology: The alternation of hard and soft layers in this lithology leads to differential erosion. Soft layers, such as mudstones and slates, are more susceptible to weathering, while the harder sandstone layers can create overhangs or ridges, leading to increased risk of landslides. The interbedding may also contribute to slope instability, and the presence of mudstone increases the risk of mudflows during periods of intense rainfall or rapid snowmelt, as these materials can become highly fluid and mobilize easily.

3.Moderately hard–moderately soft interbedded slate lithology: This lithology is prone to landslides and slope failures due to the layered nature of the slate. The moderately soft layers can become slippery when saturated with water, reducing friction and contributing to the mobilization of the slope. As the slate is often found on steep slopes, these areas are more vulnerable to slumping or rockslides, especially in areas with poor drainage or intense rainfall.

4.Hard blocky shallow igneous and volcanic rock lithology: Similar to granite and diorite, this lithology is typically resistant to weathering, which makes it relatively stable. However, volcanic rocks, such as basalt or andesite, can be prone to fracturing, which can create instability in areas with steep gradients. Volcanic rocks may also be associated with pyroclastic flows or debris flows during volcanic activity. In the event of significant rainfall or an earthquake, the loose material from volcanic deposits can lead to debris flows and landslides.

5.Soft-hard interbedded slate to sandstone lithology: This lithology exhibits a combination of soft and hard layers, leading to the same differential erosion and instability as the soft-hard interbedded sandstone, slate, and mudstone lithology. The softer slate layers are more prone to erosion, while the harder sandstone layers may create cliffs or ridges that further contribute to landslides or collapses. In addition, the slate layers can easily become saturated and act as a conduit for water, enhancing the likelihood of mudflows or debris flows, particularly in areas with high rainfall.

(10) Elevation: The terrain in the area slopes from higher elevations in the northwest to lower elevations in the southeast, with substantial elevation variation. The average elevation is 2,800 m, and the highest point is Mount Meili in the Nu Mountain Range, situated at the border between Chawalong Township and Deqin County in Yunnan Province, with an altitude of 6,817 m.

(11) Rainfall: Rainfall is the primary external factor triggering geological disasters. In Zayu County, most geological disasters are closely associated with rainfall, particularly heavy rain, torrential rain, and prolonged rainfall. Local heavy rainstorms, characterized by high intensity and long duration, often serve as direct triggers for geological events such as debris flows, landslides, and collapses.

Rainwater infiltration increases the soil’s unit weight and the slope’s self-weight, softens rock masses, and weakens the physical and mechanical properties of rock and soil, leading to slope deformation. Additionally, unregulated human engineering activities, when combined with heavy rainfall, can trigger landslides. Rainwater infiltrating rock joints increases internal static and dynamic water pressure, further reducing the mechanical strength of rock masses and causing collapses along structural surfaces.Thus, rainfall is a crucial factor in triggering geological disasters.

(12) Landform; Landform refers to terrain features that directly influence the likelihood of geological disasters. Analyzing landform characteristics identifies differences in disaster susceptibility, supporting targeted prevention efforts and resource allocation. Landform is closely linked to the formation mechanisms of geological disasters. Studying these mechanisms across different landform types provides insights into disaster causes, offering a scientific basis for prevention efforts.

Slope and aspect influence surface hydrology and sediment transport across landform types. Steep slopes increase the risk of soil sliding and collapse, while aspect affects sunlight and precipitation, influencing surface stability. The distribution of valleys and ridges plays a key role in water flow—valleys are prone to debris flows, while ridges are vulnerable to collapses.

The distribution of valleys and ridges also plays a key role in water flow patterns—valleys are more susceptible to debris flows, while ridges are prone to collapses. Additionally, landform development influences the distribution of soil layers, with differences in stability and shear strength across these layers affecting the likelihood of geological hazards. In Zayu County, landforms are classified based on factors such as absolute elevation, relative height difference, ground morphology, slope, and vegetation. The primary landform types are high mountain glaciers, high mountain canyons, high mountain wide valleys, mid-mountains, and low mountains.

The primary landform types are high mountain glaciers, high mountain canyons, high mountain wide valleys, mid-mountains, and low mountains.

Correlation analysis of conditioning factors

Correlation analysis distinguishes multiple selected factors, tests their independence, and screens out weakly correlated factors to reduce errors in the analysis.

According to correlation theory, coefficients are categorized as follows: 0.8–1.0: Very strong correlation; 0.6–0.8: Strong correlation; 0.2–0.4: Weak correlation; 0.0–0.2: Extremely weak or no correlation. When the correlation coefficient exceeds 0.6, one of the strongly correlated factors should be eliminated to avoid redundancy. Table 1 presents the correlation matrix of the 12 conditioning factors in the study area. The correlation analysis revealed a coefficient of −0.6120 between rainfall and elevation, and 0.6667 between lithology and rainfall, both indicating strong correlations. Based on the data and existing results, rainfall was eliminated. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the remaining 11 conditioning factors, and the results are shown in Table 2. Table 2 shows that the cumulative contribution of linear density of river, linear density of road, slope, lithology, peak ground acceleration, landform, and elevation is 99.10%.

Geological hazard susceptibility mapping

The flowchart of the geological disaster susceptibility evaluation framework, based on the multi-kernel density information value (MKDI) method, is shown in Fig. 5. It consists of three main components: conditioning factors, the MKDI model, and the mapping results.

Information value method

In geological hazard susceptibility mapping, the most important step is encoding the conditioning factors. The information value method, derived from information prediction theory, evaluates the correlation between factors and target research objects. In the MKDI framework, the information value method describes the relationship between conditioning factors and the susceptibility index.

In the study area \(S\), a total of \(M\) conditioning factors were identified, each corresponding to the evaluation indicator \(m\). For the geological hazard factor \(m\), the Jenks natural breaks method in ArcGIS 10.8 was used to divide it into \(N\) categories, represented by \(S_{mn}\). The information value for interval \(S_{mn}\) is represented by \(I_{mn}\), and the calculation formula of \(I_{mn}\) is as follows:

where \(I_{mn}\) represents the amount of information in interval \(n\) for factor index \(m\).

\(A_{mn}\) represents the number of geological hazards in interval \(n\) in factor index \(m\), and \(A\) is the total number of known geological hazards in the work area. \(B_{mn}\) represents the number of grid cells distributed in interval \(n\) in factor index \(m\). \(B\) is the total number of all grid cells in the study area. When \(I_{mn}> 0\), it indicates that the occurrence tendency of geological hazards is more likely in interval \(n\) in factor index \(m\). Conversely, when \(I_{mn} < 0\), it indicates that the probability of geological hazard occurrence under the corresponding factor index \(m\) and interval \(n\) is small. According to formula (1), the information of all conditioning factors in each grid can be calculated.

Kernel density estimation of geological hazard

Kernel density estimation (KDE) was introduced by Emanuel Parzen in 1962. He proposed that geographical events can occur anywhere in space, but the probability of occurrence varies across different locations. Events are more likely to occur in areas with dense points, while areas with sparse points have a lower probability of occurrence. Kernel density estimation provides the event density for each point in the region, producing a smooth kernel density map. Given the relationship between geological disasters within the study unit, kernel density estimation is employed to quantitatively analyze the spatial aggregation of geological disasters in the study area.

Kernel density estimation estimates the probability density of points in the region using a kernel function, resulting in a continuous grid density map. The grid value at any point on the map represents the kernel density, which reflects the spatial aggregation of points. The formula is:

where \(h\) represents the bandwidth; \(K()\) denotes the kernel function—typically a radially symmetric unimodal probability density function, interpreted as the weight at point \(i\); \(X_{i}\) indicates points within the bandwidth, and, \(n\) is the number of points falling within the bandwidth. The density of each output grid pixel is the sum of all kernel surface values superimposed at the pixel’s center. The primary factors influencing KDE are the mathematical form of kernel function \(K()\) and bandwidth \(h\). The choice of kernel function has minimal impact on the KDE results, while the bandwidth \(h\) determines the smoothness of the density surface and the extent of the influence range for geological hazard points. A schematic diagram of the kernel density estimation for geological hazards is shown in Fig. 6. Therefore, the results of KDE are sensitive to bandwidth, making its selection crucial. Given the varying scales of geological hazards in Zayu County, multiple bandwidths are required to capture their distribution characteristics effectively.

The multi-kernel density information value (MKDI) model

Geological hazard kernel density estimation (KDE) captures the spatial aggregation of previously occurred geological hazards. When combined with the information value method, it forms the kernel density information value (KDI) model, represented by the following formula:

where \(I^{\prime}_{mn}\) is the improved information value. For a grid cell \(x^{mn}\), the improved information value is the logarithm of the product of the original information value and the kernel density value of that point, \(A\) represents the number of geological hazards within the bandwidth \(h\), and \(X_{i}^{mn}\) denotes all grid cells within the bandwidth \(h\).

For geological hazards of different scales, appropriate bandwidths need to be selected. Therefore, the bandwidth for large-scale geological hazards is \(h_{1}\), for medium-scale geological hazards it is \(h_{2}\), and for small-scale geological hazards it is \(h_{3}\).

where \(I^{\prime\prime}_{mn}\) represents the value of the MKDI. All geological hazards are classified into three scale categories, with each category assigned a weight of 1/3. Here, \(\frac{1}{{3Ah_{1} }}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{A} {K(\frac{{x^{mn} - X_{i}^{mn} }}{{h_{1} }})}\) represents the kernel density estimation for large-scale geological hazard points, \(\frac{1}{{3Ah_{2} }}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{A} {K(\frac{{x^{mn} - X_{i}^{mn} }}{{h_{2} }})}\) represents the kernel density estimation for medium-scale geological hazard points, and \(\frac{1}{{3Ah_{3} }}\sum\limits_{i = 3}^{A} {K(\frac{{x^{mn} - X_{i}^{mn} }}{{h_{3} }})}\) represents the kernel density estimation for small-scale geological hazard points.

To verify the effectiveness of the geological disaster susceptibility evaluation model, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was used for quantitative testing. The area under the curve (AUC) is applied to assess the accuracy of the model. In recent years, the ROC curve has been widely used to evaluate the results of geological disaster susceptibility assessments.

The ROC curve plots a diagonal line from the origin (0, 0) to the upper right corner (1, 1), referred to as the chance diagonal. If the ROC curve lies on this diagonal, the AUC equals 0.5, indicating no predictive ability. In general, when AUC > 0.5, the closer the AUC is to 1, the better the model’s accuracy. Specifically: AUC 0.5–0.7: Poor accuracy, AUC 0.7–0.9: Good accuracy, AUC > 0.9: Excellent accuracy.

Results

Experimental setup

To ensure spatial uniformity across all evaluation factors and considering the study area’s scope and computational limitations, the grid cell size is set to 30 m. To validate the effectiveness of the improved information value model, the traditional information value method is used for comparison. The 85 known geological hazard points within a 300 m buffer zone serve as the sample area where the hazard probability is 1, while other areas are used as sample areas where the probability is 0. Two hundred random sample points are selected from each area for ROC accuracy testing.

Zayu County has 85 geological disasters, including 61 small, 22 medium, and 2 large events. Different bandwidths are selected for geological disasters of varying scales in this experiment. The bandwidths are set to 1.5 km for large sites, 1.0 km for medium sites, and 0.5 km for small sites.

Results of information value method

The information value for each evaluation factor and partition interval is calculated based on known disaster points and the classification intervals of each factor. Elevation, Profile curvature, Slope, Plane curvature, Linear density of water, Linear density of road is classified by natural break point method, and other factors are classified by category. The number of categories has been adjusted to ensure that geological hazards are distributed in each category. As shown in Table 3, the elevation interval with the highest information value is 1600–2300 m, with a value of 2.3956. For profile curvature, the highest information value is found in the 0–5 interval, with a value of 0.2742. For landform, the low mountain geomorphic type has the highest information value of 1.7254. In the seismic response spectrum characteristics, the highest information content category is 0.4 s with an information value of 0.4844, and in the peak ground acceleration, the highest information content category is 0.20 g with an information value of 1.0226. For aspect, the 0–90° range has the highest information value of 0.5252. For slope, the 0–10° range has the highest information value of 1.3547. For lithology, the 'relatively hard–relatively weak stratified and thin stratified schist lithofacies’ has the highest information value of 1.2453. For plan curvature, the 60–90 interval has the highest information value of 0.5718. For linear density of water, the 0.42–0.62 range has the highest information value of 1.6218. For linear density of road, the 2.85–7.3 range has the highest information value of 2.8018.

Using the traditional information value method, the information values of all grid units in the study area were calculated. The final geological disaster information value, obtained through accumulation, ranges from −13.0013 to 15.3661. The natural breaks method in ArcGIS was used to classify the information values, resulting in the geological disaster susceptibility zoning of Zayu County, as shown in Fig. 7. As shown in Fig. 7, areas with high geological hazard susceptibility are primarily distributed along roads and rivers, with sections of the G219 highway falling within high-susceptibility zones. As shown in Table 3, the information value for areas with road and route density between 2.85 and 7.3 is 2.8018. Additionally, some roads in Zayu County run parallel to rivers, resulting in high information values along these roads, though the variation within these areas is minimal. Most very high and high -susceptibility areas are concentrated along roads and rivers. High-susceptibility areas have information values ranging from 2.1280 to 15.3661, covering 9.19% of the area, with 83 geological hazard points. Moderate-susceptibility areas have information values between −2.6555 and 2.1280, covering 24.45% of the area, with 2 geological hazard points. T Low-susceptibility areas have information values between −5.9929 and −2.6555, covering 37.84% of the area, with no geological hazard points. Non-susceptible areas have information values between −13.0013 and −5.9929, covering 29.52% of the area, with no geological hazard points. These results are summarized in Table 4.

Using the G219 National Highway in Zayu County as the center and a 2000-m buffer radius, a road buffer was created. The geological disaster susceptibility results, based on the information value method, were masked to extract the susceptibility results along the G219 National Highway, as shown in Fig. 8. The information values along the highway range from −10.2920 to 15.3661.

Areas with very high and high geological hazard susceptibility are concentrated along the G219 National Highway corridor, particularly in regions with narrow canyons and steep terrain. This indicates that these regions are more prone to geological disasters, which are influenced by terrain conditions and road infrastructure construction. Areas with very low and low susceptibility are mainly distributed in broader regions surrounding the roads.

Results and analysis of KDE model

To obtain the results of the improved information value method, kernel density estimation (KDE) was performed using geological disaster points, with a bandwidth of 5 km. The kernel density estimation results for geological disaster points in Zayu County are shown in Fig. 9, with the density range varying from 0 to 1.

Based on kernel density estimation, the improved information value for each grid unit is calculated using formula (4), with the results shown in Fig. 10. The improved information value ranges from −12.30 to 21.14 and is classified using the natural breaks method. This classification identifies high-prone, medium-prone, low-prone, and non-prone areas for geological disasters in Zayu County.

Compared with the evaluation of geological hazard susceptibility based on the information value method, the results of the KDE algorithm show a reduction in the very high-susceptibility areas distributed along the road centerline in western China. The high-susceptibility areas are primarily concentrated in central regions where geological hazards occur frequently.

Additionally, highly susceptible areas appear more concentrated and continuous along key highways. Compared with the information value method, these high-risk areas are more coherently distributed along the national highway corridor. In contrast, low- and very low-risk regions are more fragmented. The figure also shows that boundaries between different susceptibility regions are clearer, with low-susceptibility areas more dispersed. Details across the entire region are more prominent.

The results indicate that the KDE algorithm improves the accuracy of transitions between regions and is more sensitive to subtle terrain and geological differences.

Results and analysis of MKDI model

Geological disasters of different scales have varying impact ranges, necessitating the use of different bandwidth parameters according to scale levels. Accordingly, under the conditions of formula (5), the bandwidth for large-scale geological disasters is set to 1.5 km, for medium-scale disasters to 1.0 km, and for small-scale disasters to 0.5 km. The optimized density results, based on the MKDI algorithm, are shown in Fig. 11. The kernel density values range from 0 to 2.50142.

By applying the information calculation formula, the geological disaster susceptibility evaluation results based on the MKDI algorithm are obtained, as shown in Fig. 12.

Compared with the KDE algorithm and the information value (IV) method, the MKDI algorithm more prominently highlights the concentrated distribution of geological hazards along the national highway. In Fig. 10, the extremely high-risk areas (red) are more concentrated and continuous than in the previous two figures, showing a clearer distribution along the main route of the G219 National Highway. In the IV-based and KDE-based results, high-risk zones are intermittently distributed along the highway. In contrast, the MKDI results present these zones more consistently, emphasizing the long-term risks along specific road sections. Additionally, low-risk areas appear more fragmented, indicating that this assessment is more sensitive to identifying risks within the central corridor of national highways. The geological hazard susceptibility evaluation results based on the MKDI algorithm are clearer and more coherent, demonstrating the superiority of this method over the KDE and IV algorithms.

Performance evaluation

To further compare and evaluate the accuracy of the IV model, KDE model, and MKDI model, the ROC curve was used to assess their performance. This experiment specifically evaluates the accuracy of geological disaster susceptibility along the G219 National Highway in Zayu County. The ROC curves of the three algorithms are presented in Fig. 13.

As shown in Fig. 13, with a buffer distance of 7 km, the IV, KDE, and MKDI models all achieve high ROC accuracy. The MKDI model achieves the highest accuracy with an AUC value of 0.990, while the IV model records the lowest with an AUC value of 0.962. The improved information method demonstrates higher accuracy than the traditional information method.

With a buffer radius of 7,000 m, summarizes the area proportions for each zone and the number of geological hazards identified by the three methods. All three methods classify approximately 40–43% of the total area as very low susceptibility, indicating broad consensus that a significant portion of the region poses minimal risk. The low-susceptibility areas remain consistent across all three methods, suggesting relative stability, with only slight variations in classification (within ± 1%). The KDE model classifies a slightly higher proportion of the area as highly susceptible than the IV and MKDI models, suggesting that KDE may be more sensitive to identifying higher-risk areas. The IV model identifies a higher proportion (8.69%) of the area as very high susceptibility than the KDE and MKDI models. This suggests that the IV method may be more conservative or cautious, identifying more extreme risk zones. The IV model classifies more area as very high susceptibility but detects fewer hazards in high-risk zones than the MKDI model, suggesting that IV may slightly overestimate extreme risks. The KDE model appears more sensitive in identifying high-susceptibility areas, reporting more hazards in these zones. However, it classifies less area as very high susceptibility than the IV and MKDI models. The MKDI model strikes a balance, identifying the most geological hazards in very high-susceptibility zones while slightly reducing the high-susceptibility area relative to the KDE model. This suggests that the MKDI model may be the most robust method for detecting precise risk zones without overestimating risk.

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of three methodologies—IV, KDE, and MKDI—based on the susceptibility levels of geological hazards (categorized as Very Low, Low, High, and Very High). The results are described in terms of the percentage of area and the corresponding number of geological hazards identified within each susceptibility level.

For the IV method, 41.52% of the area is classified as Very Low, while only 6.69% falls under the Very High category, with 13 geological hazards in the High level and 71 in the Very High level. Similarly, the KDE method identifies 41.39% of the area as Very Low and 6.46% as Very High, with 19 geological hazards in the High level and 65 in the Very High level. In contrast, the MKDI method classifies 43.27% of the area as Very Low and 6.83% as Very High, identifying a notably lower count of hazards in the High level (5) and a higher count in the Very High level (80).

Among the three methods, MKDI demonstrates a stronger discriminatory power in hazard susceptibility classification, as it identifies a larger percentage of Very High susceptibility areas (6.83%) and detects the highest number of geological hazards (80) in this category. This suggests that MKDI may be more effective in highlighting regions with critical hazard risks, which is particularly important for risk management and mitigation strategies.

Discussion

The choice of buffer distance also affects the accuracy of model evaluation. This study conducted comparative experiments using buffer distances of 2 km, 3 km, 4 km, 5 km, 6 km, 7 km, 8 km, 9 km, and 10 km to explore the optimal buffer distance. The experimental results of the three models are presented in Fig. 14.

The evaluation accuracy of the three methods fluctuates with changes in buffer distance, exhibiting a nonlinear trend, which suggests that the relationship between buffer distance and evaluation accuracy is complex.

As the buffer distance increases, the evaluation accuracy of the three methods tends to converge, though noticeable differences occur at certain distances. The accuracy of the information value (IV) method shows significant variation, especially around 5,000 m. Additionally, the IV method consistently demonstrates lower accuracy compared to the other two methods, indicating that it may not be suitable for some buffer distances.

The accuracy of the KDE method remains relatively stable across most buffer distances, with minor fluctuations, reflecting high consistency and stability. In contrast, the MKDI method achieves the highest accuracy across nearly all buffer distances, peaking between 4,000 and 7,000 m with accuracy close to 1.0. Although a slight decline is observed at larger distances, the MKDI method maintains strong overall performance.

These results indicate that the IV method is more sensitive to buffer distance, resulting in greater fluctuations and reduced applicability compared to the other two methods. The MKDI method performs well across all buffer distances and proves to be the most effective, offering both high accuracy and stability. The optimal buffer distance range for the three methods is 4,000 to 7,000 m, within which the highest evaluation accuracy is achieved.

It can be seen from the results that the final susceptibility results are related to linear density of river, linear density of road, slope and lithology. Firstly, linear density of river represents the length of rivers per unit area. Rivers can erode slopes, weakening their stability and increasing the risk of geological hazards. Areas with higher river density tend to have a higher susceptibility to such events, especially during heavy rainfall or seismic activity. Secondly, roads especially on steep slopes, disrupt natural terrain stability by cutting or filling slopes. Higher road density is linked to an increased likelihood of geological hazards due to human activity and infrastructure-related disturbances. Steeper slopes are more prone to geological hazards due to gravity. Our model identified steeper areas as having a higher likelihood of such events, consistent with the physical characteristics of unstable terrain. Finally, the composition of rocks and soils affects their resistance to erosion. Softer rocks like shale are more prone to geological hazards, while harder rocks such as granite are more stable.

The study’s limitations include the resolution of input data, which may not fully capture fine-scale variations in the terrain, especially in complex areas. Higher-resolution data would improve prediction accuracy. Additionally, the model assumes that factors remain constant over time, but in reality, factors such as land use and climate change are dynamic. Incorporating temporal variations into the model would increase its predictive capability. The model also assumes linear relationships between factors and geological hazard occurrence, which may not always hold true. Exploring non-linear interactions and using advanced techniques, such as machine learning, could help refine the model and better account for these complexities.

Future studies should focus on incorporating dynamic data, such as time-series information on climate patterns and land use changes, to improve the model’s ability to predict geological hazards under evolving conditions. Additionally, further research is needed to explore the interactions between different factors in greater detail, particularly in areas with mixed land use or complex geological settings. Machine learning techniques could be particularly useful for capturing non-linear relationships and improving the accuracy of hazard predictions. Finally, field validation of the model’s predictions against actual geological hazard events is essential to assess its real-world applicability and make necessary adjustments.

The proposed multi-kernel density information method (MKDI) effectively aligns with sustainability principles, particularly in minimizing environmental impacts and promoting resilient infrastructure development. Our method helps identify high-risk areas for geological hazards, enabling informed decision-making for infrastructure planning and disaster risk reduction. Regarding the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), MKDI supports SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) by promoting resilient infrastructure development. The method’s ability to predict and assess the vulnerability of infrastructure to geological hazards ensures that infrastructure is designed with resilience in mind, which is crucial for long-term sustainability. It also supports SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by enabling urban planners and policymakers to incorporate risk factors into urban development processes, ensuring the creation of sustainable and safe communities.

In addition, the MKDI method is scalable for large-scale infrastructure projects due to its flexibility in handling large datasets and its ability to incorporate various data layers (e.g., topography, infrastructure, climate, and geological factors). This scalability makes it highly suitable for use in large-scale urban planning frameworks, where multiple variables and spatial data need to be integrated to assess risks and make informed decisions. To incorporate MKDI seamlessly into urban planning frameworks and support infrastructure sustainability, the method can be integrated with existing geographic information systems (GIS) and urban planning software. This integration allows for real-time data analysis and hazard assessments, facilitating the inclusion of geological risk factors into infrastructure planning processes.

Conclusion

This study focuses on the G219 National Highway in Zayu County, optimizing the evaluation using kernel density estimation (KDE) in combination with the traditional information value (IV) method. An improved information value model for geological disaster susceptibility is proposed. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Performance of Different Models: The MKDI model demonstrates superior performance compared to the traditional IV and KDE models. It provides more consistent and coherent identification of high-susceptibility areas, especially along key road sections such as the G219 Highway. MKDI achieves the highest AUC value (0.990) compared to KDE (0.978) and IV (0.962), indicating that it offers the most accurate predictions.

(2) Sensitivity to Buffer Distance: The selection of buffer distance significantly influences the evaluation results. The study finds that as the buffer distance increases, the performance of all three models tends to converge. However, the IV method shows greater sensitivity and fluctuation, particularly around a 5 km buffer, suggesting that it may overestimate extreme risks at certain distances. The MKDI model maintains high stability across different buffer distances, with peak accuracy observed within the 4,000–7,000 m range.

(3) Distribution Patterns of Susceptibility:The MKDI model identifies highly susceptible zones more precisely and continuously along the G219 Highway. While the IV method tends to overestimate risks by classifying larger areas as very high susceptibility, KDE provides slightly higher sensitivity in detecting high-risk areas. However, MKDI strikes a balance by reducing overestimation and accurately pinpointing high-risk areas with consistent hazard detection.

(4) Applicability of the Models: The IV method, despite its utility, is found to be less suitable for large-scale applications due to its greater fluctuations and sensitivity to buffer distance. On the other hand, the KDE model performs better but still has limitations, particularly in the classification of very high-risk areas. The MKDI model proves to be the most robust and effective, offering both high accuracy and stability across different conditions.

(5) Optimal Buffer Distance Range: The optimal buffer distance range for evaluating geological disaster susceptibility along the G219 Highway is between 4,000 and 7,000 m. Within this range, all three models achieve their best performance, with the MKDI model consistently delivering the most accurate results.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gong, Q. Y. & Zhao, C. Study on the susceptibility of debris flow disasters in southeast Tibet based on the information content model and random forest model[C]//IOP conference Series: Earth and environmental science. IOP Publ. 1334(1), 012021 (2024).

Catani, F., Lagomarsino, D., Segoni, S. & Tofani, V. Landslide susceptibility estimation by random forests technique: sensitivity and scaling issues. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13(11), 2815–2831 (2013).

Alqadhi, S. et al. Evaluating the influence of road construction on landslide susceptibility in Saudi Arabia’s mountainous terrain: a Bayesian-optimised deep learning approach with attention mechanism and sensitivity analysis[J]. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(2), 3169–3194 (2024).

Chang, Z. et al. Landslide susceptibility prediction based on remote sensing images and GIS: comparisons of supervised and unsupervised machine learning models. Remote Sens. 12(3), 502 (2020).

Gong, W. et al. GIS-based landslide susceptibility mapping using ensemble met-hods for Fengjie County in the Three Gorges Reservoir Reg-ion. China Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19(8), 7803–7820 (2022).

Ansari, A. et al. Robustness assessment of Muscat coastal highway network (CHN) under multi-hazard scenarios focusing on traffic stability and adaptation measures[J]. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 30632 (2024).

Hussain, M. A. et al. PS-InSAR-based validated landslide susceptibility mapping along Karakorum Highway, Pakistan[J]. Remote Sens. 13(20), 4129 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Refined micro-scale geological disaster susceptibility evaluation based on UAV tilt photography data and weighted certainty factor method in Mountainous Area[J]. Ecotoxicol. & Environ. Saf. 189, 110005 (2020).

Shang, H., Liu, S. & Zhong, J. Application of Naive Bayes, kernel logistic regression and alternation decision tree for landslide susceptibility mapping in Pengyang County, China [J]. Nat. Hazards 120(13), 12043–12079 (2024).

Ansari, A. et al. Seismic vulnerability assessment and fragility analysis of tunnels in Oman: Development of risk matrices and functionality guidelines[C]//Structures. Elsevier 69, 107428 (2024).

Yang, W. et al. Geological Hazard Susceptibility Analysis and Developmental Characteristics Based on Slope Unit, Using the Xinxian County, Henan Province as an Example[J]. Sensors 24(8), 2457 (2024).

Li Z, et al. Debris flow susceptibility assessment based on topo-hydrological factors at different unit scales: a case study of Mentougou district, Beijing[J]. Environmental Earth Sciences 80, 1-19 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Comparative study of geological Hazard evaluation systems using grid units and slope units under different rainfall conditions[J]. Sustainability 14(23), 16153 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Comparison of informative modelling and machine learning methods in landslide vulnerability evaluation–a case study of Wenchuan County, China[J]. Geocarto Int. 39(1), 2361714 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping using multiple combination weighting determination: a case study of collector roads in Pingshan County, Hebei Province, China[J]. Front. Earth Sci. 12, 1403830 (2024).

Ruan, Y. et al. Assessing the susceptibility of landslides in the tuoding section of the upper reaches of the Jinsha River, China, using a combination of information quantity modeling and GIS[J]. Water 15(20), 3685 (2023).

Barman, J. & Das, J. Assessing classification system for landslide susceptibility using frequency ratio, analytical hierarchical process and geospatial technology mapping in Aizawl district NE India[J]. Adv. Space Res. 74(3), 1197–1224 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Study on Landslide Susceptibility Based on Multi-Model Coupling: A Case Study of Sichuan Province, China[J]. Sustainability 16(16), 6803 (2024).

Zhang, X., Xie, H. & Xu, Z. Evaluating landslide susceptibility: an AHP method-based approach enhanced with optimized random forest modeling. Nat. Hazards 120(9), 8153–8207 (2024).

Aziz, K., Mir, R. A. & Ansari, A. Precision modeling of slope stability for optimal landslide risk mitigation in Ramban road cut slopes, Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) India [J]. Model. Earth Syst. & Environ. 10(3), 3101–3117 (2024).

Sayyad, D., Ghasemieh, H. & Naserianasl, Z. Preparation of waterway erosion sensitivity map using data mining integrated entropy-informational value model (IOE-IV)(Case Study: The Upper Watershed of Tajan River)[J]. Quant. Geomorphol. Res. 12(4), 50–70 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Optimizing the sample selection of machine learning models for landslide susceptibility prediction using information value models in the Dabie mountain area of Anhui, China[J]. Sustainability 15(3), 1971 (2023).

He, R. et al. Application of artificial intelligence in three aspects of landslide risk assessment: A comprehensive review[J]. Rock Mech. Bull. 3(4), 100144 (2024).

Qiu, H. et al. Interpretable landslide susceptibility evaluation based on model optimization[J]. Land 13(5), 639 (2024).

Ansari, A. et al. Assessing seismic vulnerability in metro systems through numerical modeling: enhancing the sustainability and resilience of urban underground utilities (3U)[J]. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 9(10), 366 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Investigation and susceptibility assessment of regional geological hazards along the Karakoram highway, northeast margin of Pamir Plateau[J]. Geomatics, Nat. Hazards and Risk 15(1), 2341176 (2024).

Ali, S. et al. Landslide susceptibility mapping by using a geographic information system (GIS) along the China-Pakistan economic corridor (Karakoram Highway), Pakistan[J]. Nat. Hazard. 19(5), 999–1022 (2019).

Mahmood, S. et al. Rockfall susceptibility assessment along M-2 Motorway in Salt Range, Pakistan[J]. J. Appl. Geophys. 222, 105312 (2024).

Kulsoom, I. et al. SBAS-InSAR based validated landslide susceptibility mapping along the Karakoram Highway: a case study of Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan[J]. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 3344 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Hussain, M. A. & Chen, Z. Landslide susceptibility mapping with feature fusion transformer and machine learning classifiers incorporating displacement velocity along Karakoram highway[J]. Geocarto Int. 38(1), 2292752 (2023).

Ansari, A. et al. Seismic microzonation of North Gyeongsang (South Korea) considering liquefaction potential: Application towards seismic risk assessment for Korean nuclear power plants[J]. Soil Dyn. & Earthq. Eng. 182, 108679 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Influence of buffer distance on environmental geological hazard susceptibility assessment[J]. Environ. Sci. & Pollut. Res. 31(6), 9582–9595 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Evaluating expressway stability using interferometric synthetic aperture radar and measuring its impact on the occurrence of geohazards: a case study of Shanxi Province, China[J]. GISci. & Remote Sens. 60(1), 2161200 (2023).

Han, S. et al. A new approach for landslide susceptibility assessments based on KDE-MDBN: A case study from mountainous regions impacted by the Wenchuan earthquake, China[J]. Environ. Model. & Softw. 167, 105759 (2023).

Shu, B. et al. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of mountainous geological disasters in southwest China: A fine-scale multi-type assessment[J]. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 1049333 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yang Li and Yutian Lei contributed to investigation, data curation, calculation, drawing and writing-original draft. Bo Chen contributed to writing—review & editing. Jiale Chen contributed to writing—review & editing and funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

All authors declare that we have no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors declare the work described is original research that has not been published previously.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Lei, Y., Chen, B. et al. Evaluation of geological hazard susceptibility based on the multi-kernel density information method. Sci Rep 15, 7892 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91713-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91713-6