Abstract

Individuals with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) are at risk of progressing to active tuberculosis (TB), which remains a significant cause of death globally. Although various antiTB medications—rifampin and isoniazid—exist for treating for both LTBI and active TB, pharmacovigilance studies evaluating their adverse effects are especially scare for LTBI. Given the continued status of South Korea as having the highest TB incidence among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries, this study examines drug-related adverse events (AEs) and identifies novel signals associated with rifampin or isoniazid in TB prevention and treatment in South Korea using the national AE reporting system. Analyzing data from the Korea Institute of Drug Safety and Risk Management-Korea Adverse Event Reporting System Database (KIDS-KAERS DB, 2301A0006) between 2017 and 2021, we observed that rifampin was frequently listed as a suspected drug in AE reports. Serious adverse events (SAEs), including life-threatening events and hospitalizations, were observed in LTBI as well as active TB cases when rifampin was the suspected drug. Novel signals, including QT prolongation and acne, were also identified, underscoring the importance of AE monitoring in LTBI or active TB treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) ranks foremost in causing global mortality. Approximately one in four people worldwide is infected with TB, and 5–10% of these people will ultimately progress to active TB1,2. It primarily spreads through airborne aerosols carrying Mycobacterium tuberculosis, emitted from patients with TB3,4. When patients are infected with TB, most remain asymptomatic and lack radiological or microbiological evidence, entering a state known as latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), where the disease remains dormant5. However, the risk of progression from LTBI to active TB is highest within the first two years, with elderly and immunocompromised individuals at particularly higher risk2,6.

Many countries in North America, Europe, and Asia have initiated national policies and programs to eradicate the TB epidemic. The United Nations has discussed about TB eradication polices and agreed to reduce TB incidence by 2030. Additionally, the United States, China, and India have implemented national programs to control TB1,7. Among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, South Korea currently maintains the highest TB incidence rate8. To reduce TB incidence, South Korea has established a TB control framework aimed at treating LTBI and preventing the onset of active TB9. Thus, early identification and treatment of LTBI are crucial for reducing TB incidence rates. The preferred treatment for LTBI involves a rifampin-based regimen, which includes either a 3-month combination therapy of rifampin plus isoniazid (3 h) or 4-month rifampin monotherapy (4R), followed by either 6 or 9 months isoniazid monotherapy10,11. Since adverse drug reactions (ADRs) from rifampin or isoniazid can lead to treatment discontinuation, identifying any previously unknown AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs) is crucial to improve adherence to LTBI treatment.

While ADRs are collected and assessed during preclinical and clinical trials, the reporting of ADRs may be limited owing to the relatively short treatment period and restricted number of study participants. Therefore, post-marketing surveillance is crucial, as it allows for the identification of a wide range of ADRs in real-world settings12. Korea Adverse Event Reporting System (KAERS) enables both healthcare professionals and consumers to voluntarily report AEs online or via telephone. This system provides crucial information on AEs, suspected drugs, patients, and reporters. Once an AE report is submitted, the Korea Institute of Drug Safety & Risk Management (KIDS) collects the information to build a database for signal detection and pharmacovigilance research. These pharmacovigilance data can then inform updates to drug labels and may serve as foundational evidence for establishing regulatory policies.

While various randomized control trials, cohort studies, and retrospective studies have evaluated active TB drugs13,14,15,16, pharmacovigilance studies investigating AEs of rifampin or isoniazid in patients with LTBI in South Korea remain unknown. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the spontaneous AE reports associated with isoniazid and rifampin in both TB prevention and treatment and identify any novel signals related to rifampin and isoniazid, in order to assess AE profile of isoniazid and rifampin in the real-world setting.

Results

Retrieval of AE reports from the KAERS database

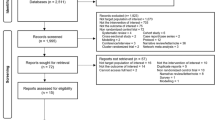

Between 2017 and 2021, the KAERS received 1,308,059 AE reports. Among these, 1,256,598 were retained after selecting only final reports and removing prior versions. Reports that were incomplete or canceled were excluded (n = 3,812), resulting in a final dataset of 5,623,522 drug-AE pairs including concomitant drugs. From this dataset, we focused on suspected drug-AE pairs, totaling 1,546,185, which included pairs related to rifampin or isoniazid (n = 8,426) and other drugs (n = 1,537,759) (Fig. 1).

Flowchart illustrating the selection process of adverse event (AE) reports from the Korea Adverse Event Reporting System (KAERS). AE reports extracted from the KAERS system, spanning between 2017 and 2021. Only the first or most recent completed reports were included and reports that were incomplete or canceled reports were excluded. Finally, suspected causative drugs associated with AEs were paired together. Suspected drugs were categorized into rifampin, isoniazid, or others drugs group.

Patient demographics

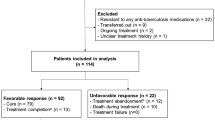

Most AE reports related to rifampin and isoniazid originated from spontaneous reports submitted to regional pharmacovigilance centers (Table 1). These reports were mainly submitted by medical professionals, including doctors, pharmacists, and other healthcare practitioners such as nurses. For rifampin, a total of 3,560 AE reports were observed in TB diagnosis, followed by cases categorized as “others” (N = 1239) and then LTBI (N = 262). In diagnosis of LTBI, individuals aged 50–59 years old reported 84 AE reports within their group, while those aged ≥ 65 years in active TB categories exhibited 1,454 AE reports. For isoniazid, individuals aged 40–49 years in the LTBI diagnosis reported two AE cases, while individuals aged 50–59 years in the active TB group exhibited 18 AE cases. Figure 2 presents the analysis of SAEs and signal detection results for rifampin and isoniazid as suspected drugs by diagnosis: LTBI, active TB, and others. Specifically, for rifampin in LTBI, eight signals and 46 SAEs were identified. For isoniazid in LTBI, no signals and SAEs were observed.

Analysis of adverse event (AE) reports after using rifampin or isoniazid. AE reports associated with rifampin and isoniazid were categorized into three groups based on TB diagnosis including active TB, latent TB, and others. Signals and SAEs were analyzed within each group. Novel signals of AEs were detected and documented using drug labels from the Korea Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

SAEs of Rifampin and Isoniazid

In LTBI, a total of 19 out of 262 cases (7.25%) involving rifampin as a suspected drug was observed to have SAEs such as death, life-threatening events, hospitalization, serious disability, and congenital anomalies. No SAEs were reported for isoniazid. In patients with active TB or others, SAEs were reported in 150/3560(4.21%)−86/1239(6.94%) for rifampin and 9/51(17.65%)−2/18(11.11%) for isoniazid, respectively (Table 2). When SAEs were categorized based on system organ class (SOC) and preferred terms (PTs), rifampin was associated with 46 symptoms in patients with LTBI. Skin reactions such as pruritus, rash, urticaria, and pyrexia were among the frequently reported symptoms in SAEs (Supplementary Table 1). In isoniazid, no report of SAE was recorded for patients with LTBI, while two symptoms were reported for SAEs, such as visual impairment and rash in patients with other diagnoses (Supplementary Table 2). Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 present symptoms that are categorized as PTs in SAEs for active TB and other diagnoses.

Signal detection of Rifampin and Isoniazid

Signals, defined as statistically significant adverse reactions, were reported for rifampin as a suspected drug in patients with LTBI (Table 3). Upper abdominal pain, pyrexia, fatigue, rash, elevated hepatic enzymes, aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and blood bilirubin were identified as signals and were listed as AEs in the Korea Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) or U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) label. These signals were also categorized as signals of active TB or other diagnoses (Supplementary Table 3). However, signals including blurry vision, weight loss, QT prolongation, gout, increased sputum, drug eruption, and acne were newly identified AEs in patients with active TB that were not listed in the MFDS and FDA labels (Table 3). In patients with other diagnoses, 32 signals were detected, with four signals—blurry vision, weight loss, maculopapular rash, and drug eruption—not listed in the MFDS and FDA (Supplementary Table 3).

Regarding isoniazid, no signal was found in patients with LTBI. However, ten signals, including QT prolongation, cataract, peripheral edema, hypoesthesia, and back pain, were newly detected as AEs of isoniazid in patients with active TB. These signals were not listed in the Korea MFDS or U.S. FDA labels. Additionally, one novel signal, urticaria, was detected in patients with other diagnoses, which was not included in the MFDS or FDA label (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4). The concomitant drugs administered alongside standard antiTB drugs, such as rifampin, isoniazid, ethambutol, or pyrazinamide, are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Discussion

This study is significant as it is the first to investigate AEs associated with latent TB drugs using spontaneous AE reports in South Korea. Previous studies have primarily focused on AEs of antiTB drugs in patients diagnosed with active TB17,18. Currently, pharmacovigilance studies on latent TB drugs such as rifampin and isoniazid remain poorly investigated because it is generally assumed that the use of antiTB drugs presents relatively low safety concerns. However, variations in the drug combination, frequency of use, and treatment duration between latent and active TB potentially result in varying types and frequencies of AEs. Reports of AE and SAEs associated with rifampin as a suspected drug were frequently reported. In Korea, the most frequently used therapy for LTBI is the 3 h therapy, followed by rifampin and isoniazid10. For active TB, most patients received treatment with a combination of isoniazid and rifampin. Most AE reports contained rifampin as the suspected drug, but the reasons for this addition remain unclear. Since rifampin is a potent inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes19, the possibility of drug-related AEs may be higher than isoniazid. In addition, clinical trials comparing rifampin 4-month therapy with isoniazid 9-month therapy have reported higher rates of treatment completion and safety with rifampin 4-month therapy than with isoniazid 9-month therapy20.

In the latent TB group, there were 19 SAEs following rifampin use, including hospitalization (N = 11), others (N = 6), and life-threatening events (N = 2) (Table 2). This suggests that monitoring AEs in patients with latent TB may be as crucial as those with active TB; therefore, caution is needed for patients who are undergoing rifampin treatment. AEs that occur during latent TB treatment can decrease medication adherence and potentially result in treatment failure. A randomized trial conducted in the United States and Canada revealed that a considerable number of patients did not complete LTBI treatment due to AEs21. Therefore, research on AEs is essential to determine potential AEs and establish management strategies in advance. This can enhance medication adherence and offer patients crucial information about possible AEs. The centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) also recommends monitoring AEs and medication adherence in patients undergoing LTBI treatment during routine hospital visits at the start of therapy22. In addition, the Korean tuberculosis guidelines emphasize the importance of monitoring LTBI treatment. During the initial post-treatment visit, liver function and bilirubin tests are conducted, alongside a complete blood count if the patient is undergoing rifampin treatment. Subsequently, if patients exhibit abnormal liver function test results or risk factors for liver disease, monthly liver function tests are recommended23.

The active TB group showed eight newly detected signals following the use of rifampin and ten newly detected signals following the use of isoniazid. This may be attributed to the frequent use of drug combinations in active TB treatment, typically involving four drugs: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. The study revealed several novel signals in patients with active TB treated with rifampin or isoniazid, including QT interval prolongation on electrocardiograms (ECGs) and eye disorders. QT interval prolongation was observed only in patients with active TB and not in those with latent TB, indicating that patients with active TB should be more cautious about changes in their ECGs compared to those with latent TB. Particularly, QT interval prolongation can lead to Torsades de pointes (TdP)—a cardiac arrhythmia linked to fainting or fatal cardiac arrest24. Thus, unmodifiable risk factors for QT prolongation, such as female sex, elderly, genetic predisposition, and history of previous drug-induced QT prolongation should be identified. Additionally, modifiable risk factors such as electrolyte imbalance (e.g. low potassium, magnesium, or calcium levels), pre-existing heart conditions, and drug interactions with QT-prolonging drugs should be monitored and managed25,26,27. To predict the risk of QT prolongation, various QT prolongation risk assessment tools such as MedSafety Scan QT prolongation risk score tool can be used. Patients with risk factors who are receiving high risk of QTc-prolonging drugs such as antiarrhythmics are advised to undergo baseline ECG and regular ECG monitoring. Patients with risk factors receiving moderate-risk QTc-prolonging drugs such as bedaquiline, delamanid, fluoroquinolones, or antifungals or those receiving high-risk QTc-prolonging drugs are recommended to check a baseline ECG and have their ECG monitored when the drugs reach steady state concentration25. Patients with active TB treated with rifampin or isoniazid in combination with fluoroquinolones showed incidences of QT prolongation (Tables 4 and 5). Likewise, Heemskerk et al. reported that patients with tuberculosis meningitis assigned to the intensified-treatment group consisting of a combination of rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and levofloxacin had a higher incidence of QT prolongation than those in the standard-treatment group receiving rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol28. This highlights the need for caution when administering rifampin and isoniazid for treating active TB along with fluoroquinolones, as these combinations have the potential to cause QT prolongation. Therefore, it is recommended to check for potential drug-drug interactions using drug information databases when adding a new medication for patients with active TB. Additionally, the frequency of monitoring should be increased when prescribing drugs that carry a risk of QT interval prolongation.

Regarding novel signals related to eye disorders, blurry vision was observed in patients undergoing rifampin treatment, while cataract was identified in patients undergoing isoniazid treatment (Table 3). Blurry vision and cataracts have been reported as possible ocular disorders in patients with active TB and treated antiTB drugs29,30,31. Therefore, evaluating the ocular effects of rifampin or isoniazid monotherapy in patients with TB in future studies would be beneficial. Additionally, weight loss was another signal reported in patients with active TB treated with rifampin along with fluoroquinolone (Table 4). Similarly, Laohapojanart et al. reported that patients with tuberculosis assigned to the study group that received the standard oral antiTB drug regimen along with antiTB dry powder inhaler consisting of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin experienced weight loss compared to the control group that received only the standard oral antiTB drugs32. Drug eruption was reported in patients with active TB treated with rifampin along with fluoroquinolones (Table 4). According to Kong et al., a patient with active TB receiving rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and levofloxacin developed a drug eruption33. Moreover, acne was observed in patients with active TB treated with rifampin. Studies have documented acneiform eruptions in patients using antiTB drugs, including isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol34,35. However, it remains uncertain whether rifampin specifically causes acne. Therefore, further investigation is necessary to assess the association between acne occurrence and rifampin in patients with active TB. To the best of our knowledge, no study has utilized global databases such as the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) or the World Health Organization (WHO) VigiBase to investigate these novel signals. Therefore, this study may provide new insights into treating patients with TB using rifampin or isoniazid. In summary, the signals we identified, such as those related to rifampin (e.g., QT prolongation, acne, blurred vision) and isoniazid (e.g., cataracts, QT prolongation, peripheral edema), are challenging to directly associate with the mechanisms of these drugs. Isoniazid, for instance, is known to cause hepatotoxicity36, which can interfere with drug metabolism in the liver and increase the levels of certain drugs, thereby increasing the likelihood of adverse effects due to drug interactions. On the other hand, rifampin, a potent inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes, can accelerate drug metabolism37. Consequently, rifampin may trigger adverse effects by interacting with other drugs. Therefore, careful attention is required regarding potential drug interactions. Given the results of this study, which show the difference in AEs from the same drugs between active and latent TB, further studies using real-world data may be warranted to validate the relationship between the drug and novel signal. For patients starting therapy with rifampin or isoniazid, baseline eye exam and follow-up visits may be considered for those at high risk or with preexisting eye conditions. If blurry vision or cataract is significant, the healthcare provider may consider temporarily discontinuing the medication and arranging comprehensive eye exam. Additionally, adjusting the dose or switching to alternative TB drugs may be considered. Proactive monitoring for eye disorders could facilitate early detection and intervention, minimizing the risk of lasting ocular damage. Additionally, given the potential for acne development in patients receiving rifampin, healthcare providers should consider counseling patients on this possibility and discuss dermatologic management options38 if acne adversely impacts patient adherence.

This study has some limitations associated with its utilization of the KAERS database. First, as AEs are obtained from a spontaneous reporting system, there is a concern regarding potential over-reporting or under-reporting of AEs, as well as instances of incomplete or delayed reporting. This may affect the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the AE data, as cases could be exaggerated or missed depending on discretion of individual reporters and the circumstances of reporting. Additionally, missing or delayed reporting could introduce bias, limiting the study’s ability to capture the full spectrum of AEs. Second, further in-depth analyses such as stratified and multivariate analyses performed on real-world data from electronic health records or claims databases could not be conducted due to limitations in the existing data within the spontaneous adverse event reporting system. Third, the quality and accuracy of AE reports may vary depending on the type of reporter. Forth, AE analysis is limited to drugs that were identified as suspected drugs, restricting the generalizability of findings across a broader range of drug exposures. Finally, AEs observed in multidrug therapies, such as rifampin plus isoniazid combination therapy, may not adequately indicate the AEs from causative drugs due to potential subjective bias in selection of suspected drug by individual reporter. In our study, relatively fewer AEs were observed with isoniazid compared to rifampin as the suspected drug. Given the common use of rifampin and isoniazid in combination therapy for both active and latent TB, it is a possible that rifampin was selected as the suspected drug despite the concurrent administration of isoniazid. Therefore, the possibility of underreporting of AEs for isoniazid cannot be ruled out. Despite these limitations, this study holds significance, as it examined the AEs associated with latent TB drugs in Korea, a representative country in Asia. It utilized data managed by the KIDS, which collects nationwide AE reports in South Korea. Since globally collected drug AE information is accessible through databases such as VigiBase, a side effect reporting database of WHO in Europe, and FAERS, an AE reporting system of the FDA in the U.S.A., utilizing the KAERS database, enables the evaluation of differences in AEs based on the ethnicity and baseline characteristics of Koreans.

In conclusion, we collected spontaneous AE reports from the KAERS database and evaluated the SAEs associated with rifampin and isoniazid, commonly used drugs for latent TB, among patients diagnosed with active TB, LTBI, and other diagnoses. We observed a high frequency of SAEs in patients with LTBI who were treated with rifampin. Therefore, it is crucial to inform patients with LTBI about the potential ADRs associated with these medications, and healthcare professionals should remain vigilant for any SAEs that can occur with rifampin or isoniazid. In addition, novel signals such as QT prolongation and acne were identified in patients using rifampin or isoniazid. Therefore, further investigation using real-world data from electronic health records or claims databases, with adjustments for concomitant medications and comorbidities, is necessary to determine whether the identified signal is drug-induced and to validate the clinical relevance of these findings.

Methods

Adverse event reporting system database

We used KAERS DB (2301A0006), which contained spontaneously reported AEs between 2017 and 2021, which KIDS provided. Each AE report included patient demographics, past medical history, AE, drug information, active ingredient, dosage, indication, and causality assessment information.

The drug indications were identified using the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD) code. Drugs were categorized as suspected, concomitant, drug interactions, or unadministered drugs. Suspected drugs were those potentially linked to adverse reactions, concomitant drugs were administered to patients experiencing adverse reactions, and drug interactions were drugs suspected of interacting with others.

For analysis, we included final AE reports, incorporating initial reports when follow-up reports were unavailable. We excluded AE reports that were incomplete or canceled before forming drug-AE pairs. Additionally, AE reports missing ingredient code information were excluded. Within the same AE report, cases where the active ingredient and adverse event were identical but differed in administration details, such as dosage, dosing interval, start and end dates, formulation, or route of administration, were considered a single adverse event (e.g., Vomit - Isoniazid 50 mg, Vomit - Isoniazid 100 mg → Vomit - Isoniazid) to avoid redundancy. By selecting only suspected drugs that were not concomitant, we extracted 1,546,185 suspected drug-AE pairs.

Ethical declarations

This study was exempted from ethical review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungpook National University (IRB No. 20220085), and the requirement for informed consent was also waived by the same IRB. The exemption from full ethical review was granted because only anonymized data on spontaneously reported AEs related to drug use were utilized, eliminating any potential for identifying individual patients. Consequently, informed consent was waived, as there was no direct patient interaction or use of identifiable private information. This exemption complies with guidelines of Kyungpook National University IRB on the ethical use of anonymized secondary data for research purposes. All procedures were rigorously conducted in accordance with Kyungpook National University IRB regulations to uphold research integrity and protect data privacy.

Study drugs and population

To study the AEs of latent TB drugs, the investigation primarily focused on AE reports associated with rifampin (M code: M020042) and isoniazid (M code: M040493), which were extracted from the KAERS database. AE reports involving drugs other than isoniazid and rifampin were utilized as controls for signal detection. The AE reports associated with rifampin and isoniazid were categorized based on drug indications. These indications included active TB (KCD code: A15-19), latent TB (KCD code: R76.8), and others (other KCD codes or missing information). The “other” KCD codes encompass diseases beyond TB, such as pulmonary mycobacterial infections (KCD code: A31.0), preventive measures (KCD code: Z29), unspecified meningitis (KCD code: G03.9), and post-herpetic neuralgia (KCD code: G53.0).

We categorized AE report data for isoniazid or rifampin obtained from the KAERS database according to patient demographics, including TB diagnosis (active TB, LTBI, and others), sex, age group, type of reporter, source of report, and report type.

Definition of adverse events and serious adverse reaction

AEs spontaneously reported in the KAERS DB were initially coded based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities Lowest Level Term (MedDRA LLT). If AEs were coded using the World Health Organization Adverse Reaction Terminology (WHO-ART) by the original reporter, they were converted to the MedDRA LLT by KIDS. In the analysis of AE reporting data for this study, LLT was categorized into PT using the MedDRA version 26.0 SOC. SAEs can be categorized into six: death, life-threatening events, hospitalization, serious disability, congenital anomaly, and other important medical conditions. Other significant medical conditions encompass issues such as drug dependence, drug abuse or misuse, and hematologic complications. The reporter determined and checked which of the six categories applied, and multiple categories could be selected for a single report.

Data mining, signal detection, and statistical analysis

We employed disproportionality analysis for drug monitoring, utilizing data mining techniques. This approach detects signals through parameters such as proportional reporting ratio (PRR), reporting odds ratio (ROR), and information component (IC). PRR and ROR are measures that assess the relative frequency of an AE reported for a specific drug compared to other drugs, while IC uses a Bayesian statistical model to identify the difference between the observed and expected reporting frequencies for a drug-event pair to detect signals. A signal is defined as information suggesting a potential causal relationship between the study drugs and AEs. Table 6 presents the equation used to calculate the signal. When the three data mining parameters—PRR, ROR, and IC—met the predefined criteria with a significance threshold of p= 0.05, the corresponding signals were considered statistically significant. These methodologies are widely recognized in pharmacovigilance research. Disproportionality analyses require a minimum of 5,000 reports to reduce the likelihood of false-positive signals39, and this study satisfies this criterion by utilizing a large national-level spontaneous adverse event reporting database. Statistical correction such as the Bonferroni adjustment was not applied, as it could reduce the potential for identifying novel signals40. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze patient demographics and AEs. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). In this study, specific methods for handling missing data and outliers were not applied, as these factors were not included in the analysis. Importantly, there were no missing values for suspected drugs or AEs.

We verified the presence of precautions in the drug labels for each medication for AE reports identified as signals. Drug label information was confirmed using two databases: the Korea Ministry of Food and Drug Safety’s Integrated Information System for Pharmaceuticals (https://nedrug.mfds.go.kr/index) and the U.S. FDA Online Label Repository (https://labels.fda.gov/). AE reports identified as signals but not listed in the drug label were categorized as novel signals.

Data availability

This study used KAERS DB (2301A0006), which contained spontaneously reported adverse events between 2017 and 2021, which KIDS provided. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to KIDS; Official website of https://nedrug.mfds.go.kr/bbs/148#none.

References

Bai, W. & Ameyaw, E. K. Global, regional and National trends in tuberculosis incidence and main risk factors: a study using data from 2000 to 2021. BMC Public. Health. 24, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17495-6 (2024).

Zhu, P. et al. Incidence and risk factors of active tuberculosis among older individuals with latent tuberculosis infection: a cohort study in two high-epidemic sites in Eastern China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1332211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1332211 (2024).

Nduba, V. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cough aerosol culture status associates with host characteristics and inflammatory profiles. Nat. Commun. 15, 7604. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52122-x (2024).

Frieden, T. R., Sterling, T. R., Munsiff, S. S., Watt, C. J. & Dye, C. Tuberculosis Lancet 362, 887–899, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14333-4 (2003).

Behr, M. A., Kaufmann, E., Duffin, J., Edelstein, P. H. & Ramakrishnan, L. Latent tuberculosis: two centuries of confusion. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 204, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202011-4239PP (2021).

Xie, X., Li, F., Chen, J. W. & Wang, J. Risk of tuberculosis infection in anti-TNF-alpha biological therapy: from bench to bedside. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 47, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2013.03.005 (2014).

Harding, E. WHO global progress report on tuberculosis elimination. Lancet Respir Med. 8, 19. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30418-7 (2020).

Im, C. & Kim, Y. Spatial pattern of tuberculosis (TB) and related socio-environmental factors in South Korea, 2008–2016. PLoS One. 16, e0255727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255727 (2021).

Cho, K. S. Tuberculosis control in the Republic of Korea. Epidemiol. Health. 40, e2018036. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2018036 (2018).

Lee, J., Kim, D., Hwang, J. & Kwon, J. W. Incidence of tuberculosis disease in individuals diagnosed with tuberculosis infection after screening: A population-based cohort study in South Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 141, 106961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2024.02.004 (2024).

Sterling, T. R. et al. Guidelines for the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: recommendations from the National tuberculosis controllers association and CDC, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 69, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6901a1 (2020).

Alomar, M., Tawfiq, A. M., Hassan, N. & Palaian, S. Post marketing surveillance of suspected adverse drug reactions through spontaneous reporting: current status, challenges and the future. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 11, 2042098620938595. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098620938595 (2020).

Albanna, A. S., Smith, B. M., Cowan, D. & Menzies, D. Fixed-dose combination antituberculosis therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir J. 42, 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00180612 (2013).

Gallardo, C. R. et al. Fixed-dose combinations of drugs versus single-drug formulations for treating pulmonary tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD009913, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009913.pub2 (2016).

Kim, H. J. et al. Real-world experience of adverse reactions-necessitated rifampicin-sparing treatment for drug-susceptible pulmonary tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 13, 11275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38394-1 (2023).

Yagi, M. et al. Factors associated with adverse drug reactions or death in very elderly hospitalized patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 13, 6826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-33967-6 (2023).

Chung, S. J., Byeon, S. J. & Choi, J. H. Analysis of adverse drug reactions to First-Line Anti-Tuberculosis drugs using the Korea adverse event reporting system. J. Korean Med. Sci. 37, e128. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e128 (2022).

Kwon, B. S. et al. The high incidence of severe adverse events due to Pyrazinamide in elderly patients with tuberculosis. PLoS One. 15, e0236109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236109 (2020).

Grange, J. M., Winstanley, P. A. & Davies, P. D. Clinically significant drug interactions with antituberculosis agents. Drug Saf. 11, 242–251. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-199411040-00003 (1994).

Menzies, D. et al. Four months of Rifampin or nine months of Isoniazid for latent tuberculosis in adults. N Engl. J. Med. 379, 440–453. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1714283 (2018).

Moro, R. N. et al. Factors associated with noncompletion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment: experience from the PREVENT TB trial in the united States and Canada. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, 1390–1400. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw126 (2016).

Huaman, M. A. & Sterling, T. R. Treatment of latent tuberculosis Infection-An update. Clin. Chest Med. 40, 839–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2019.07.008 (2019).

Korean Guidelines For Tuberculosis. (Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2024).

Tisdale, J. E. Drug-induced QT interval prolongation and Torsades de pointes: role of the pharmacist in risk assessment, prevention and management. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott). 149, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/1715163516641136 (2016).

Khatib, R., Sabir, F. R. N., Omari, C., Pepper, C. & Tayebjee, M. H. Managing drug-induced QT prolongation in clinical practice. Postgrad. Med. J. 97, 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138661 (2021).

Lopez-Medina, A. I., Chahal, C. A. A. & Luzum, J. A. The genetics of drug-induced QT prolongation: evaluating the evidence for pharmacodynamic variants. Pharmacogenomics 23, 543–557. https://doi.org/10.2217/pgs-2022-0027 (2022).

Al-Khatib, S. M., LaPointe, N. M., Kramer, J. M. & Califf, R. M. What clinicians should know about the QT interval. Jama 289, 2120–2127. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.16.2120 (2003).

Heemskerk, A. D. et al. Intensified antituberculosis therapy in adults with tuberculous meningitis. N Engl. J. Med. 374, 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507062 (2016).

Tsui, J. K. S., Poon, S. H. L. & Fung, N. S. K. Ocular manifestations and diagnosis of tuberculosis involving the Uvea: a case series. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines. 9, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40794-023-00205-w (2023).

Kokkada, S. B. et al. Ocular side effects of antitubercular drugs - a focus on prevention, early detection and management. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. (KUMJ). 3, 438–441 (2005).

Egbagbe, E. E. & Omoti, A. E. Ocular disorders in adult patients with tuberculosis in a tertiary care hospital in Nigeria. Middle East. Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 15, 73–76. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.51996 (2008).

Laohapojanart, N., Ratanajamit, C., Kawkitinarong, K. & Srichana, T. Efficacy and safety of combined isoniazid-rifampicin-pyrazinamide-levofloxacin dry powder inhaler in treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis: A randomized controlled trial. Pulm Pharmacol. Ther. 70, 102056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2021.102056 (2021).

Kong, D. et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic Symptoms-Associated perimyocarditis after initiation of Anti-tuberculosis therapy: A case report. Cureus 15, e37399. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.37399 (2023).

Kazandjieva, J. & Tsankov, N. Drug-induced acne. Clin. Dermatol. 35, 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.10.007 (2017).

Sharma, R. P., Kothari, A. K. & Sharma, N. K. Acneform eruptions and antitubercular drugs. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 61, 26–27 (1995).

Metushi, I., Uetrecht, J. & Phillips, E. Mechanism of isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity: then and now. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 81, 1030–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12885 (2016).

Baciewicz, A. M., Chrisman, C. R., Finch, C. K. & Self, T. H. Update on Rifampin, Rifabutin, and rifapentine drug interactions. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 29, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2012.747952 (2013).

Reynolds, R. V. et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 90, 1006. .e1001-1006.e1030 (2024).

Caster, O., Aoki, Y., Gattepaille, L. M. & Grundmark, B. Disproportionality analysis for pharmacovigilance signal detection in small databases or subsets: recommendations for limiting False-Positive associations. Drug Saf. 43, 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-020-00911-w (2020).

Perneger, T. V. What’s wrong with bonferroni adjustments. Bmj 316, 1236–1238. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by funding from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT of the Korean government (Grant number: NRF-2022R1A2C1004822). This research was supported by BK21 FOUR Community-Based Intelligent Novel Drug Discovery Education Unit, Kyungpook National University. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L., and J-W.K. designed the study. Y.L. collected the data. J.R., Y.L., and J-W. K. analyzed and interpreted the data. J.R., Y.L. wrote the first draft. J.R. and J-W.K. revised the manuscript. J-W.K. acquired funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ryu, J., Lee, Y. & Kwon, JW. Analysis of nationwide adverse event reports on Isoniazid and Rifampin in tuberculosis prevention and treatment in South Korea. Sci Rep 15, 7411 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91753-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91753-y