Abstract

COPD exacerbations have a profound clinical impact on patients. Accurately predicting these events could help healthcare professionals take proactive measures to mitigate their impact. For over a decade, telEPOC, a telehealthcare program, has collected data that can be utilized to train machine learning models to anticipate COPD exacerbations. The objective of this study is to develop a machine learning model that, based on a patient’s history, predicts the probability of an exacerbation event within the next 3 days. After cleaning and harmonizing the different subsets of data, we split the data along the temporal axis: one subset for model training, another for model selection, and another for model evaluation. We then trained a gradient tree boosting approach as well as neural network-based approaches. After conducting our analysis, we found that the CatBoost algorithm yielded the best results, with an area under the precision-recall curve of 0.53 and an area under the ROC curve of 0.91. Additionally, we assessed the significance of the input variables and discovered that breathing rate, heart rate, and SpO2 were the most informative. The resulting model can operate in a 50% recall and 50% precision regime, which we consider has the potential to be useful in daily practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic respiratory disease that serves as a paradigm for chronic diseases. With a high global prevalence (12.16%)1,2 it represents a significant health burden3. During the course of the disease patients may experience deterioration of their baseline clinical status (exacerbation), occasionally requiring hospitalization to control such worsening. In COPD, the baseline disease severity and hospitalizations due to COPD exacerbations (eCOPD) are the two factors that most significantly impact on direct costs4. Furthermore, hospitalizations also have a profound clinical impact on patients, leading to a loss of pulmonary function5, deterioration of health-related quality of life in the short and long term6,7, heightened risk of cardiovascular events8, increased mortality9, and greater probability of short-term readmission10. This cycle of hospitalization and readmission not only escalates costs but also perpetuates adverse outcomes for patients.

The current situation has spurred various interventions aimed at modifying the sequence of negative events associated with eCOPD. These interventions involve predicting the risk of severe eCOPD (hospitalization)11 or readmissions10,12, as well as early detection of eCOPD13, particularly in patients with a higher likelihood of admission14. This notion of anticipation and the tools that support it represent a new care paradigm for chronic diseases, particularly COPD, which would necessitate a redesign of the chronic disease care model.

In this new scenario, telemonitoring and Machine Learning are expected to play crucial roles in changing clinical practice. Although telemonitoring has been a controversial tool in managing eCOPD13, it may be necessary to establish an adequate patient profile to achieve success14. Additionally, telemonitoring can provide a continuous and well-structured stream of quality data that can be leveraged with Machine Learning techniques. These techniques can learn and uncover relationships and patterns that are not visible to traditional methods currently in use.

At the hospital of Galdakao, we developed a telemonitoring program (telEPOC)14,15,16 aimed to monitor COPD patients that have been frequently admitted for COPD exacerbation to the hospital. The main goal of this program is to reduce the number of admissions to the hospital, and its results so far have been very satisfactory (the program has been spread to other hospitals of the Basque Government Health Department). It has also been shown that this program improves several aspects of health care of patients with respect to those in the control group14.

In this study, our objective is to develop an early warning system based on Machine Learning (telEPOCML) that can predict when a patient in the telEPOC program is likely to experience a red alarm (i.e., the highest level of alarm, see14 for more details). In other words, we aim to anticipate eCOPD in our cohort of telemonitored patients.

Methods

Telemonitoring data set

The telEPOC dataset is composed of the daily questionnaires submitted by patients on a daily basis. More specifically, the dataset is composed of the following variables:

-

SpO2: Measured by a pulse oximeter.

-

Heart Rate: Measured by a pulse oximeter.

-

Breathing Rate: Manually measured respiratory rate.

-

Number of Steps (previous day): Measured with a pedometer.

-

Temperature.

-

Do you have fatigue? (Yes/No).

-

Do you have more fatigue than usual? (Yes/No).

-

Do you have a cough? (Yes/No).

-

Do you have more coughing than usual? (Yes/No).

-

Do you have sputum? (Yes/No).

-

Is your sputum amount increased, the same, or decreased compared to usual? (Increase/Same/Decrease).

-

What is the color of your sputum? (White / Greenish yellow / With blood).

-

How are you feeling in general? (Better/Equal/Worse).

-

Are you feeling better, equal, or worse than usual? (Better/Equal/Worse).

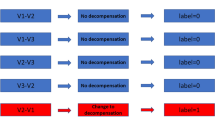

Based on these reports and a set of rules, an alarm system with three levels is established14. The highest level, which indicates a severe exacerbation, is labeled as a red alarm.

The dataset is subdivided into three subsets as a result of the different software platforms used to collect the data. Table 1 shows the characteristics of each data subset. Due to major changes in the data acquisition process and alarm definitions, the subset 1 was left out of this project.

In total, 166 COPD patients from the TelEPOC program were included in this study (74.7% men, 15% current smokers). Table 2 presents baseline characteristics obtained from the medical records available in the hospital for these patients. These characteristics are not part of the TelEPOC dataset and were not used to train the machine learning models. Instead, they are included to provide additional context regarding the demographic, clinical, and physiological profiles of the study population, enhancing the interpretability of our results.

Data cleaning and harmonization

The data cleaning and harmonization steps consisted of fixing wrongly labeled alarms, harmonizing categorical variable values that changed over time, removing unreliable time periods when that happened during back end migrations, removing duplicate submissions and removing unrealistic values. Table 3 shows the range of allowed values for the different variables.

Sometimes, patients make mistakes while submitting their daily data. In such cases, they send a second submission to correct their errors. During the data cleaning process, we only retain one submission per day. We prioritize the values submitted in the most recent submission. Additionally, variables and categorical values have been modified throughout the program. Therefore, we performed necessary operations to standardize them without compromising the information.

In addition, we excluded samples where the patient was already in a red alarm state. However, we noticed that the model achieved significantly better scores when we retained these samples in the dataset. This was likely due to the fact that patients in a red alarm state are much more likely to experience another red alarm the following day than those who are not. Nevertheless, we believe that such predictions are of limited value in daily practice. This is because doctors are already aware of the patients’ condition, and consecutive days with a red alarm can be considered as part of the same exacerbation period. Therefore, we concluded that it would be more appropriate and realistic to exclude these samples from the model’s training and evaluation.

After these pre-processing steps, we combined it to create a single dataset. The final dataset consisted of 149 patients and 159,719 samples. It covers a time frame from 09-29-2014 to 05-19-2021.

Model input and target variables

The target variable that we chose to predict is whether a patient will experience a red alarm within the next three days. As part of the data preprocessing, we computed this target variable for each patient submission.

The model utilizes the patient’s submitted data from the previous days to make this prediction. We experimented with different numbers of previous days, which we referred to as the input window size. After testing, we selected an input window size of 11 days (current day plus a historical window of 10 days) for our final model. This window size yielded the best results among the ones we tested. Additionally, it corresponds to our clinical observations and the findings reported in other studies17.

Besides, our model will use the medium term statistics for each patient at the time of each submission. Specifically, in order to allow the model to find both patterns in the raw data as well as deviation from individual baseline values, we add new variables with mean, median and standard deviation from the last 4 months prior to each submission for temperature, heart rate, number of steps and breathing rate variables.

Experimental setup

We split the dataset into three subsets along the temporal axis. The first subset, which contains 75% of the samples, is the train set used to train the model. The second subset is the validation set, comprising 15% of the samples, used for model selection. The third subset is the holdout test set, also consisting of 15% of the samples, used to evaluate the selected model’s performance on unseen data.

Splitting the data along the temporal axis, rather than splitting by patients, ensures that the model is trained on data preceding the validation and test sets, mimicking real-world scenarios. It also enables us to assess the model’s ability to generalize to new data by testing it on the holdout test set, which covers a time period the model has not previously encountered, thus reducing the risk of information leakage from the train set to the test set.

Alternatively, we could divide the dataset based on the patient axis, resulting in each split consisting of a group of patients and their complete temporal sequence. This approach offers the advantage of preventing the model from learning patient-specific patterns, which can enhance its ability to generalize to new patients. However, this setup could potentially leak patterns specific to a particular moment in time to the test set. Furthermore, it is less representative of the real-world use case than the temporal split.

Additionally, a prospective dataset containing 14,253 samples was collected. This extra dataset was used to conduct a real-world validation of the final model, assessing its performance beyond the original train–validation–test split.

Models

We tried multiple machine learning models to find the most suitable one for the red alarm prediction task, specifically gradient tree boosting (CatBoost), feedforward neural networks, and convolutional neural networks. The selection of these three approaches was motivated by their complementary strengths. Gradient tree boosting excels with tabular data and provides feature importance rankings, making it particularly valuable for clinical applications where model interpretability is crucial. Feedforward neural networks can capture complex non-linear relationships and are adept at processing high-dimensional healthcare data. Convolutional Neural Networks, particularly 1D CNNs, are effective for time series data, automatically extracting relevant features from temporal structures. All three methods have proven track records in healthcare applications, can handle longitudinal data effectively, and have well-established implementations, making them suitable choices for this prediction problem. By employing these diverse algorithms, we aimed to explore different approaches to modeling the complex patterns in COPD exacerbation data, ultimately selecting the best-performing model for our task.

Training and model selection

We conducted a random search of hyperparameters for all models and chose the one that performed the best on the validation set. We evaluated the performance of all models based on both the Area under the ROC curve (AUROC) and the Area under the Precision-Recall curve (AUPRC). We selected the AUPRC as our primary metric for model selection because it better reflects model performance in our heavily imbalanced dataset—one in which non-exacerbations greatly outnumber exacerbations—and it directly captures the trade-off between recall and precision for the positive (exacerbation) class.

While AUROC is a useful measure of overall discrimination, it does not reflect the false positive rate’s impact on model applicability in real-world scenarios. A model with high AUROC can still generate an impractical number of false positives in an imbalanced dataset, which can overwhelm clinical teams, causing alarm fatigue and undermining the system’s utility. In contrast, AUPRC focuses on the balance between identifying true positives (recall) and avoiding false positives (precision), which is essential for a model to be actionable in practice.

Results

Table 4 shows the performance of each model when using an input window size of 11 days and selecting the hyperparameters that provided the highest AUPRC in the validation set. As can be seen, the catboost model outperforms the neural network approaches. We also Ran experiments with other gradient tree boosting approaches, such as LightGBM and XGBoost, which provided almost identical but slightly worse results than catboost.

We conducted experiments with varying input window sizes to observe how scores change as we alter the number of recent days that the model can use to make predictions. Table 5 displays the catboost model scores when utilizing input windows of only the current day, the current day + 10 days, and the current day + 20 days. We observed that this parameter appeared to be more critical for the AUPRC metric and we chose to employ the current day + 10 days version for the remainder of the study, since it provided the best result for both AUROC and AUPRC.

The detailed results for the catboost model are shown in Table 6, where “AUPRC random” contains the area under the Precision-Recall curve obtained by random predictions (the AUROC for random predictions is always 0.5).Figures 1, 2 and 3 depict the AUROC and AUPRC curves for the train, validation, and test sets, respectively.

Model interpretability

To achieve a more interpretable model that would allow us to examine the importance of each variable, we trained a model on a simplified dataset without temporal windows. Specifically, we excluded the 10-day history and the 4-month summary, and focused solely on a single submission to predict the probability of a red alarm within the next three days. The experiment was conducted using the same data splits as the previous experiment. Table 7 presents the scores obtained from this experiment. As we can see, the results are significantly worse than those of the previous experiment. This demonstrates the importance of the 10-day history and the 4-month summary, which provide valuable information for the red alarm prediction task. Figures 3, 4, 5 and 6 depict the AUROC and AUPRC curves for this experiment.

To ensure that our model had learned meaningful relationships and to identify the most informative variables for the task at hand, we conducted a SHAP analysis on the simplified dataset. SHAP is a game-theoretic approach that attributes the contribution of each feature to the output. We can see the results of this analysis in Fig. 7, which shows how breath rate, heart rate and SpO2 are the three most informative variables to predict red alarms with the CatBoost model trained on the simplified dataset.

Prospective analysis and applicability

After training our best CatBoost model, an additional dataset was collected in order to perform a prospective analysis. Specifically, we used data submitted from 2021-05-20 until 2022-01-30, with a total number of 14,253 samples.

The scores obtained in this subset were similar to the previous ones. Table 8 shows the scores achieved and Fig. 8 their corresponding curves.

One potential application of this system in the real world is to perform a thorough assessment on patients who, while not experiencing a red alarm, have the highest risk scores according to our model. To evaluate this approach using our prospective dataset, we identified 63 days during the prospective period when at least 30 patients had complete information for model evaluation. Specifically, these were days when no patient currently had a red alarm, the target label could be computed for the next three days, and the patients had no missing data in the previous 10 days. We then examined how many red alarms could have been anticipated by selecting the “n” patients with the highest score predicted by our model on these 63 days. To compare the effectiveness of this approach, we also examined the number of red alarms that would have been anticipated by randomly selecting “n” patients instead. The results of this experiment are presented in Table 9. We observed that if we had selected the five patients with the highest predicted scores according to our CatBoost model, we would have identified 107 patients who later experienced a red alarm. In contrast, if we had randomly selected five patients each day, we would have identified only 23.5 ± 1.30 patients who later experienced a red alarm. These findings suggest that our model can effectively identify patients at higher risk of experiencing a red alarm, and that this approach could be a valuable tool for healthcare providers seeking to prioritize patient care.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical approval was obtained from the Comité de Ética de la Investigación de Euskadi (Euskadi Research Ethics Committee), with project ID PI2019038. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Discussion

There is no definitive, universally accepted definition of eCOPD (GOLD23). The definition is inherently subjective, primarily due to patient input data but also influenced by healthcare providers, resulting in a lack of objective data to support the diagnosis of eCOPD. This is why some experts refer to the diagnosis of eCOPD as an exclusion diagnosis. In our telEPOC program, we were able to reduce the hospitalization rate for eCOPD by 40% compared to a hospital control (14). However, despite this improvement, some patients still required hospitalization. Consequently, our next step was to attempt to anticipate the deterioration of the patients’ condition. In this paper, we aimed to identify the clinical deterioration of symptoms (a “red alarm”), which we used as a surrogate marker for exacerbation. It is important to note that a “red alarm” does not necessarily indicate an exacerbation; rather, it serves as an indicator of potential deterioration and prompts healthcare providers to take appropriate actions within the telEPOC program.

We will center the discussion on articles focused on predicting COPD patient deterioration using solely telemedicine data.

In18, the authors used a telemonitoring system to collect pulse rate, oxygen saturation, and breathing rate as well as symptoms such as chest tightness, breathlessness and sputum for 110 COPD patients monitored for 1 year. They identified stable and prodromal states and built a model to classify patients’ status into one of the two states. Their exacerbation events are defined as changes in medication, and therefore they pursue a different target that the one presented in this work. They achieve an AUROC of 0.682.

In19, the authors use 68,139 self reports from 2374 patients to define COPD exacerbation events based on the reported symptoms, and then they build a model to anticipate events that would happen within the next three days. They didn’t have access to measurements such as SpO2 or temperature. They achieved an AUROC of 0.727.

In20, the authors argue that using classic algorithms to establish eCOPD events leads to too many false-positive alarms, rendering them impractical for daily use. Instead, they focus on forecasting two targets within the next 24 h: hospitalization and initiation of oral steroids. To achieve this, the authors utilized 363 days of telemonitoring data from 135 patients. Their approach resulted in an AUROC of 0.74 for hospitalization prediction, corresponding to a 40% false-positive rate for an 80% recall rate. For anticipating the initiation of steroids, their model resulted in an AUROC of 0.765. The authors demonstrate how their Machine Learning approach produces better results for these tasks than the standard algorithms used to define exacerbations.

As an example of what can be achieved by including clinical markers, in21, the authors developed a model to classify patients as being in a mild state or a severe condition. Their input data included 24 features, such as Neutrophil count and Eosinophil count from blood test analysis. They experimented with several Machine Learning models and, similar to our study, found that the Gradient Tree Boosting approach performed the best, with an AUROC of 0.963. Interestingly, they also discovered that a naive ensemble of their models improved the best model’s score, resulting in an AUROC of 0.968. Additionally, among their 24 variables, the authors reported that the second most informative feature for their ensemble model was the weight of the patients, which is a variable that could potentially be added to our model as an input.

After reviewing these studies, we discovered that our dataset contains a larger number of data points compared to the others. This indicates that the quality and size of our dataset played a significant role in achieving the best AUROC score (0.91) among the presented articles. However, as pointed out in20, a high false-positive rate is the main factor that limits the practicality of these models in daily use. The precision or positive predictive value is the metric that should be reported to assess the number of false alarms generated in comparison to the true alarms. Therefore, we believe that this type of work should report the AUPRC, which reflects the model’s precision and recall performance. It is worth noting that a random model will always achieve an AUROC score of 0.5, and the score remains the same regardless of the positive to negative ratio. However, a random model’s AUPRC score is equal to the prevalence of positive labels. Consequently, the lower the prevalence, the harder it is to achieve a high AUPRC score, making it difficult to use this metric to compare models trained on datasets with different ratios of positive events. None of the related works we reviewed report this metric. In our case, we achieved an AUPRC score of 0.53, allowing us to identify a threshold to operate in a regime with 50% recall and 50% precision.

One limitation of our study is its reliance on data from a specific cohort of patients in the telEPOC program, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations or healthcare settings. Additionally, the use of the red alarm as a surrogate marker for exacerbation, while practical, may not fully capture the complexity of COPD exacerbation events. These factors should be considered when interpreting our results and designing future studies.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Buist, A. S. et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD study): A population-based prevalence study. Lancet 370, 741–550 (2007).

Varmaghani, M. et al. Global prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. East. Mediterr. Health J. 25, 47–57 (2019).

Quaderi, S. A. & Hurst, J. R. The unmet global burden of COPD. Glob. Health Epidemiol. Genom. 3, e4 (2018).

Gutiérrez Villegas, C., Paz-Zulueta, M., Herrero-Montes, M., Parás-Bravo, P. & Madrazo Pérez, M. Cost analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): A systematic review. Health Econ. Rev. 11(1), 31 (2021).

Donaldson, G. C., Seemungal, T. A. R., Bhowmik, A. & Wedzicha, J. A. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 57, 847–852 (2002).

Esteban, C. et al. Impact of hospitalizations for exacerbations of COPD on health-related quality of life. Respir Med. 103, 1201–1208 (2009).

Miravitlles, M. et al. Effect of exacerbations on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A 2 year follow up study. Thorax 59, 387–395 (2004).

Dransfield, M. T. et al. Time-dependent risk of cardiovascular events following an exacerbation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Post hoc analysis from the IMPACT trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e024350 (2022).

Soler-Cataluña, J. J. et al. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 60, 925–931 (2005).

Quintana, J. M. et al. ReEPOC-REDISSEC group. Predictors of short-term COPD readmission. Intern. Emerg. Med. 17, 1481–1490 (2022).

Jones, R. C. et al. Derivation and validation of a composite index of severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: The DOSE index. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 180, 1189–1195 (2009).

Almagro, P. et al. Working group on COPD, Spanish society of internal medicine. Short- and medium-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation: The CODEX index. Chest 145, 972–980 (2014).

Pinnock, H. et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 347, f6070 (2013).

Esteban, C. et al. Outcomes of a telemonitoring-based program (telEPOC) in frequently hospitalized COPD patients. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 11, 2919–2930 (2016).

Esteban, C. et al. Cost-effectiveness of a telemonitoring program (telEPOC program) in frequently admitted chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J. Telemed Telecare 2021, 1357633X211037207

https://ec.europa.eu/eip/ageing/repository/telemonitoring-copd-patients-frequent-hospitalizations_en

Donaldson, G. C. & Wedzicha, J. A. COPD exacerbations.1: Epidemiology. Thorax 61(2), 164–168 (2006).

Shah, S. A., Velardo, C., Farmer, A. & Tarassenko, L. Exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Identification and prediction using a digital health system. J. Med. Internet. Res. 19(3), e7207 (2017).

Chmiel, F. P. et al. Prediction of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation events by using patient self-reported data in a digital health app: Statistical evaluation and machine learning approach. JMIR Med. Inf. 10(3), e26499 (2022).

Orchard, P. et al. Improving prediction of risk of hospital admission in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Application of machine learning to telemonitoring data. J. Med. Internet. Res. 20(9), e263 (2018).

Hussain, A. et al. Forecast the exacerbation in patients of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with clinical indicators using machine learning techniques. Diagnostics 11(5), 829 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Departments of Health of the Basque Government (2016111055).

Funding

for this study was provided by GSK. GSK was provided the opportunity to review a preliminary version of this manuscript for factual accuracy, but the authors are solely responsible for final content and interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.E., J.M., A.A., and L.C. collected patient data through the telemonitoring program, ensuring data accuracy and completeness. They also contributed to the experimental design, offering clinical knowledge to refine the study’s objectives and methodology, and participated in the interpretation of the results, helping to contextualize the findings within the broader clinical landscape.C.E.A. and P.G. played pivotal roles in the technical aspects of the study, designing experiments, ensuring scientific rigor and validity, and performing in-depth data analysis using machine learning and statistical methods. Their contributions were essential in shaping the direction and outcomes of the research.F.S. provided technical and scientific support, collaborating with C.E.A. and P.G. in refining the experimental design and data analysis strategies. His expertise in AI and machine learning was instrumental in optimizing the models and algorithms, leading to improved predictive performance and more reliable results.J.A.G., F.J.C., S.R., and D.S., as part of the IT group, provided essential support to the study by contributing to the setup and maintenance of the technical infrastructure necessary for the telemonitoring program, ensuring its smooth operation throughout the study period. They were also involved in developing and implementing data extraction and normalization processes, ensuring that the collected data was suitable for analysis and could be effectively utilized by the research team.C.E., J.M., A.A., L.C., C.E.A., P.G., and F.S. were involved in the writing process of the paper, collaborating to synthesize the findings, discuss the implications, and craft a clear text.All the authors have read and reviewed the document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moraza, J., Esteban-Aizpiri, C., Aramburu, A. et al. Using machine learning to predict deterioration of symptoms in COPD patients within a telemonitoring program. Sci Rep 15, 7064 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91762-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91762-x