Abstract

Cropping systems may affect root decomposition and our objective was to evaluate chemical characteristics and root decomposition in signal grass ‘Basilisk’ [Urochloa decumbens (Stapf) R.D. Webster] pastures under different cropping systems. A split-split plot scheme, with four cropping systems (0, 50, 100 kg·ha−1 of N, and intercropping with calopo (Calopogonium mucunoides Desv.) in the plots (paddocks), two experimental periods (2019/2020 and 2020/2021) in the split-plots, and nine incubation times (4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 days) in the split-split plots, in a randomized block design with two replications was used. Root biomass was not affected (p > 0.05) by cropping systems (7.4 t ha−1 on average). Before incubation, ADIN-TN (acid detergent insoluble nitrogen in total nitrogen) concentration was affected by cropping systems and C concentration was affected by interaction cropping systems x period. The remaining biomass had a loss total of 28% (1st ) and 30% (2nd ) after 512 d. N concentration was higher in the 1st period, resulting in a lower carbon: nitrogen ratio. Higher lignin concentration was observed for 0 kg·ha−1 of N (1st ) and 50 kg·ha−1 of N (2nd ). The ADIN concentration was higher in 100 kg·ha−1 of N than others systems. The lignin: N and lignin: ADIN ratios decreased over time. Although the root litter decomposition was not affected by the cropping systems, a potential average input of 18.6 kg·ha−1 of N was observed after 512 days.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meet production systems that rely on pastures as the primary feed source are considered more cost-effective and sustainable, due to its potencial greenhouse gas emissions mitigation1and efficiency in storing carbon (C) in the soil2.

The easy propagation of signal grass ‘Basilisk’ [Urochloa decumbens(Stapf.) R.D. Webster] via seeds, its low soil fertility requirements, and its good adaptability to soils with high acidity are responsible for its wide use in tropical regions3. However, the lack of replacement of the nutrients removed from the soil by plants, especially because of the high cost of these inputs, leads to pasture degradation, with extensive areas of degraded pastures occurring in tropical regions, with very high costs for recovery, and which limit animal productivity and increase greenhouse gas emissions4.

Studies evaluating the decomposition of fine roots have gained prominence due to their implications for C and N cycles, as well as for the global C balance5,]6. Approximately 22% of primary production in plants is destined for fine roots7, which are roots less than 2 mm in diameter and of great importance for soil quality, as through their decomposition directly contribute to the entry of C and other nutrients into the soil improving its quality8.

Studies that evaluated nutrient cycling in pastures via root decomposition have highlighted the influence of several factors on the degradation of organic material over time. These include plants species, chemical composition of the substrate9,]10, exogenous factors such as temperature and humidity conditions11and nitrogen sources12,]13. The introduction of N via biological N2fixation or N fertilization can affect nutrient cycling directly by favoring the decomposition of existing litter12and indirectly through altering the quality of the material to be decomposed12,]14.

The introduction of legumes such as calopo (Calopogonium mucunoidesDesv.), which is well-adapted to acidic and low-fertility soils15, is an effective strategy for incorporating nitrogen into systems, thereby reducing dependence on chemical nitrogen fertilizers16, while also improving soil quality by enhancing the diversity of plant root composition and morphology, the incorporation of plant residues from diverse origins at varying depths17, as well as relative root decomposition [18]. However, the impact of calopo on root decomposition in pastures is not fully understood.

In the present study, we hypothesized that introducing N to signal grass (U. decumbens) pastures, via chemical fertilization or intercropping with calopo (C. mucunoides Desv.) would change the quality of the residues and accelerate root decomposition. Therefore, our objective was to evaluate the root biomass and its decomposition, and the root chemical composition before and during 512 days of incubation, from signal grass ‘Basilisk [Urochloa decumbens (Stapf) R.D. Webster] pastures under different cropping systems: unfertilized (U0), fertilized with 50 kg·ha−1 (U50) or 100 kg·ha−1 (U100) of nitrogen, or intercropped with calopo (C. mucunoides Desv.) (UC), over two periods.

Materials and methods

Experimental location

The experiment was conducted in the Unit for Teaching, Research and Extension in Forage, at the Federal University of Viçosa, in Viçosa, Minas Gerais (20°46′34″S, 42°51′55″W), in a pasture of signal grass ‘Basilisk’ [Urochloa decumbens (Stapf) R.D. Webster] managed under deferred grazing during the dry season. The incubation study was conducted over two periods: period 1, from January 25, 2019 to June 20, 2020 (2019/2020, 512 days), and period 2, from January 31, 2020 to June 25, 2021 (2020/2021, 512 days).

The average annual precipitation at the site is 1.340 mm and the relative humidity is 80%. The accumulated rainfall during the experimental periods was 2.464 and 2.217 mm for periods 1 (Jan/2019 to Jun/2020) and 2 (Jan/2020 to Jun/2021), respectively (Fig. 1)19.

Monthly weather conditions at Unit for Teaching, Research and Extension in Forage, Viçosa, MG, during the experimental periods. Rainfall, cumulative monthly rainfall; Min. Temp., monthly mean minimum temperature; Max. Temp., monthly mean maximum temperature19.

The soil is classified as a Red-Yellow Oxisol with a clayey texture20. The soil chemical analysis was carried out in the 0–10 cm layer before correction and fertilization (December 2018), indicated the following values: pH (H2O 1:25) = 5.1; P (Mehlich-1 extractor) = 6.35 mg·dm−3; K (Mehlich-1) = 136.0 mg·dm−3; Ca2+ = 2.12 cmolc·dm−3; Mg2+ = 0.73 cmolc·dm−3; Al3+ = 0.2 cmolc·dm−3; H + Al = 7.76 cmolc·dm−3; sum of bases = 3.20 cmolc·dm−3; cation exchange capacity = 10.95 cmolc·dm−3; base saturation = 29.4, and OM = 5.11 dag·kg−1.

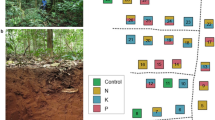

Experimental design and treatments

The data were analyzed using a split-split plot scheme, with four cropping systems (U0, U50, U100, and UC) in the plots (paddocks), two experimental periods (2019/2020 and 2020/2021) in the split-plots, and nine incubation times (4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 days) in the split-split plots, in a randomized block design with two replications. The cropping systems consisted of unfertilized signal grass ‘Basilisk’ [Urochloa decumbens (Stapf) R.D. Webster] (U0), signal grass fertilized with 50 kg·ha−1 N (U50), signal grass fertilized with 100 kg·ha−1 N (U100), and signal grass intercropped with calopo (Calopogonium mucunoides Desv.) (UC). The paddocks (experimental units) had an average area of 1300 m2.

Pasture management

Signal grass pastures were established in 1997, and calopo was sown in four paddocks in the experimental area in January 2017 and reseeded in December 201721. The Calopogonium mucunoides seeds were bought from a seed company. Based on the soil chemical analysis, necessary liming and fertilization were carried out according to Ribeiro et al.22, considering a medium technological level. Dolomitic limestone was applied in September 2018 through broadcast, at a dose of 483 kg·ha−1. At the beginning of the first experimental period, phosphate fertilizer was broadcast at a dose of 33.8 kg·ha−1 of P2O5, using simple superphosphate as the source.

The pastures were managed under mob-stocking protocol during the rainy season and the pre- and post-grazing heights were 25 cm and 15 cm, in both experimental years. Nelore cows with an average body weight of 465 kg were used as defoliation agents. Pastures were closed at the end of the rainy season on April 29, 2019 and April 2, 2020.

The day after the animals left the paddocks, N fertilization was carried out in four paddocks per block, that received a dose equivalent to 50 kg·ha−1·year−1 of N or 100 kg·ha−1·year−1 of N, using urea as the source. Pastures remained closed until July 1, 2019 (63 days of deferral) and until July 11, 2020 (101 days). The proportions of calopo in the intercropped systems were 11.3% and 9.6% on dry matter basis, in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Root biomass

Root biomass was determined, in the 0–20 cm layer, in June 2019 and June 2020. Root samples were collected using an iron cylinder, measuring 10.8 cm in diameter and 20 cm in height. Three soil samples (soil + roots) were collected in each experimental unit (paddock). The samples were dried at 55 °C in an oven with forced air circulation, until a constant mass was achieved, and weighed. Roots were separated from the clods of soil, with the aid of tweezers, gently washed over a sieve with running water to remove all adhering soil and placed in identified plastic pots. After that, roots were dried at 55 °C, until constant mass, and weighed. Root biomass in the 0–20 cm layer (t·ha−1) was estimated based on soil density (t·m⁻³), the soil volume in 1 ha at a depth of 0–20 cm (2000 m3), the root biomass (kg) contained in each soil sample and the total weight of the sample (soil + roots, kg).

Root Preparation and incubation

The roots were collected from the 0–20 cm layer in October 2018 and October 2019, with the aid of a post hole digger. Six soil samples (soil + roots) were collected in each experimental unit (paddock).

Roots were separated from the soil with the aid of tweezers, washed over a sieve with running water and dried at 55 °C in an oven with forced air circulation, until a constant mass was achieved. Part of the root samples (± 15 g) was ground in a Willey mill with a 1 mm sieve, and the chemical composition was analyzed to represent the zero-incubation time (non-incubated samples).

The root samples were incubated in January 2019 and January 2020, in nylon bags with 75 μm pores, measuring 15 × 30 cm23,]24. For each treatment, four bags were prepared per incubation time, three of which received 12 g of root sample each, and one “blank” (without sample). The nylon bags were buried (incubated) in soil (20 cm deep) in four paddocks per block (samples from each treatment in its corresponding paddock), totaling eight paddocks. Eight incubation periods were studied (4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 days), as described by Silva et al.24. A total of 512 bags were incubated (four bags/incubation time × eight incubation times × four treatments × two field replicates per treatment × two experimental periods).

After collection, the bags were cleaned with a paintbrush, dried in an oven at 55 °C with forced air circulation until a constant mass was achieved, and weighed to determine the remaining biomass. Subsequently, the samples were ground in a Willey mill with a 1 mm sieve and analyzed for chemical composition.

Root chemical composition

The chemical composition of root samples non-incubated (“zero” time) and samples incubated for different times were analyzed. The concentrations of OM (method 942.05)25, lignin (sequential method)26, N (method 976.05)25, and acid detergent insoluble nitrogen (ADIN)26were determined. The C content was analyzed using the Dumas method (AOAC 968.06)25, using a Vario EL III analyzer (Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Langenselbold, Germany). Root C: N, lignin: N, and the ADIN-TN were calculated by dividing the C, lignin and ADIN contents (g·kg–1 OM) by the total N concentration (g·kg–1 OM), respectively. Lignin: ADIN ratio was obtained by dividing lignin concentration by the ADIN content (g·kg–1 OM).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using a split-split-plot scheme, with four cropping systems [unfertilized signal grass (U0), signal grass fertilized with 50 kg·ha−1 N (U50), signal grass fertilized with 100 kg·ha−1N (U100), and signal grass intercropped with calopo (UC)] (plots/paddocks), two experimental periods (2019/2020) (split-plots), and nine incubation times (4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 days) (split-split plots) in a randomized block design, with two replications. The data were analyzed by adjusting for mixed linear models27, with the MIXED procedure in the SAS Studio (version 3.71; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The effects of treatments, periods, and incubation times were considered fixed, and blocks, plots, split-plots, and splitsplit plots errors were considered random effects. All variance components were estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood method. Means were estimated using the LSMEANS function, and comparisons were made between treatments and periods using Tukey’s test at 5% probability. When the effect of the incubation time was significant, the nonlinear regression models were adjusted using the Double Exponential Model.

Results

Root biomass

The root biomass was not affected by cropping systems (P = 0,6207) or years (P = 0,6477), with an average value of 7.4 t·ha−1 (Table 1).

Root chemical composition before incubation and N accumulation

The chemical composition of the signal grass pasture roots before incubation (day 0) is presented in Table 2. There was an effect of the systems x year interaction (p < 0,05) on C concentrations. In the first year, a higher C concentration was found in the incubated roots of the U0 and U100 cropping systems, an intermediate value for UC, and a lower C concentration for U50. However, there was no difference in C concentrations in the second year. There was an individual effect of systems only on ADIN-TN concentrations (g ADIN·kg−1 N), being lower for UC in relation to U0 and intermediate for U50 and U100. The concentrations of N and ADIN were higher in year 1, while the lignin: ADIN ratio was lower in that year. The accumulation of N (kg·ha−1 ) in the root biomass was calculated by multiplying the concentration of N (g·kg−1 of OM) in the roots by the root biomass (kg·ha−1 of OM) for each treatment.

Root biomass decomposition

The remaining biomass was affected by the interaction between incubation period and incubation time (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2). This process was explained by a double-exponential decay curve in both periods. In period 1, a 19% loss of biomass was observed in the first 128 days, followed by a gradual loss of incubated biomass, with a total loss of 28% after 512 days. In period 2, a significant loss of biomass was initially observed, where 22% of the incubated biomass was lost in the first 32 days of incubation, which stabilized after 128 days, resulting in a total loss of 30% of the incubated biomass after 512 days.

Chemical composition of incubated root

Carbon concentration was not affected by the cropping systems (P = 0.3280), but an interaction effect of period x times of incubation was observed (P = 0.0058) (Fig. 3). The C content decreased in both periods; however, at the end of the second period its concentration was 66% higher than that at the end of period 1, varying from 308 to 126 g·kg−1 and from 320 to 209 g·kg−1 in periods 1 and 2, respectively.

An interaction effect was observed between the period and incubation time for N content (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a) and the C: N ratio (P = 0.0080) (Fig. 4b). The concentration of N in the incubated samples increased over time, more significantly throughout period 1 than in period 2, reaching values of 20.02 and 15.12 g·kg−1 OM, after 512 days, in periods 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 3a). This increase in N content contributed to a reduction in the root C: N ratio during both periods, which decreased over time, varying from 62 to 7 in Period 1 and from 60 to 14 in Period 2 (Fig. 4b).

In this study, considering a mean value of 7.4 t·ha−1 for root biomass and the averages of N concentrations in the roots, in the first and second year, the N accumulation calculated was 72.5 and 56.2 kg·ha−1 N (Table 2), respectively. Considering the remaining biomass obtained (Fig. 2), the mean potential input of N to the soil, via roots, would be 20.3 and 16.9 kg·ha−1, for first and second period, at the end of 512 days of incubation. Although there was no systems effect, the N input was 20.7, 17.9, 16.4 and 19.2 kg·ha−1, for U0, U50, U100, and UC, respectively.

Lignin concentration was affected by the triple interaction between cropping systems, periods, and incubation times (P = 0.0011) (Fig. 5a and b). In the first period of decomposition, an increase in lignin concentration was observed over time for the U50 and UC treatments; however, in U0 and U100, the lignin concentration stabilized after 128 days (Fig. 5a). During this period, the lignin concentration varied between 233 g·kg−1 OM (U0) and 302 g·kg−1 OM (UC) at the end of 512 days. In the second period, only in the U50 system was there no tendency towards stabilization of the lignin concentration over time, showing a high lignin content (255 g·kg−1 OM) after 512 days (Fig. 5b).

Lignin content in signal grass pasture roots under different cropping systems, in periods 1 (a) and 2 (b), throughout the incubation times. Vertical bars indicate the mean standard error (U0, unfertilized signal grass; U50, signal grass fertilized with 50 kg ha−1 N; U100, signal grass fertilized with 100 kg ha−1 N; UC, signal grass intercropped with calopo).

An interaction effect was observed between cropping systems and incubation times (P = 0.0210) (Fig. 6) for ADIN concentration (in g·kg−1 OM). The lowest concentration was observed in U50, reaching an average value of 6.9 g·kg−1 OM after 512 days (Fig. 6).

ADIN content in signal grass pasture roots under different cropping systems, throughout incubation times. Vertical bars indicate the mean standard error (U0, unfertilized signal grass; U50, signal grass fertilized with 50 kg ha−1 N; U100, signal grass fertilized with 100 kg ha−1 N; UC, signal grass intercropped with calopo).

An interaction effect was observed between the period and incubation time for the lignin: N (P = 0.0107) and lignin: ADIN (P < 0.0001) ratios. A double-exponential decay model was used to fit the data. The lignin: N ratio decreased over time, varying from 32 to 29 at the beginning of periods 1 and 2, respectively, to 13 on day 512 (Fig. 7a). The lignin: ADIN ratio varied from 74 to 48 during the first period and stabilized after 400 days of incubation (Fig. 7b). In the second period, a more pronounced reduction was observed in this variable, varying from 97 to 18 after 512 days. At the end of period 2, the lignin: ADIN ratio was 2.7 times lower than that observed at the end of period 1.

Discussion

The lack of effect of the cropping systems on root biomass was unexpected, given the wide range of values observed (Table 1). However, there is a tendency indicating that U0 exhibits higher root biomass compared to systems receiving nitrogen. According to the literature, plants supplied with a N source tend to allocate more biomass to shoots28 at the expense of roots. However, this tendency was not statistically significant in the present study.

Studies have reported that the inclusion of legume species into grassland pastures have increased N content, which impacts other variables such as C: N and lignin: N ratios29,]30. However, the evaluation of the chemical composition before incubation showed that the variables studied were not affected by the cropping systems, with the exception of C e ADIN-TN concentrations (Table 2). It was found that roots from the first incubation period had high N content. Nevertheless, a large portion of this nutrient was associated with the fibrous fraction, such as ADIN (Table 2), making soluble nutrients less available for decomposing microorganisms31.

According to Castanha et al.10, precipitation and humidity can also affect root decomposition. Therefore, the slow and gradual degradation of root residues that occurred at the beginning of the first incubation period reflects the low rainfall observed at the beginning of that period (Fig. 2). Moreover, the C content reduced over time mainly at the end of first period, and this pattern may be influenced by the high volume of precipitation observed between October/2019 and March/2020 (Fig. 1).

In the second period, climatic conditions favored the decomposition process, as more than half of the entire volume of precipitation occurred in the first months of root incubation. Furthermore, roots incubated during this period showed low concentrations of ADIN (Table 2), a recalcitrant compound whose high concentrations slow down decomposition. Thus, more pronounced decomposition occurred in the first 64 days of incubation (Fig. 2), making nutrients more rapidly available in the soil solution. Therefore, the highest precipitation associated to the lowest initial root ADIN content, favored faster decomposition of root residues. Assessing root decomposition in elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureumSchum.) over two periods of 512 days of incubation, higher decomposition in the second period was reported and attributed to greater rainfall and chemical composition of the roots24.

The increase in N concentration in the incubated material over time (Fig. 4a) contributed to a reduction in the root C: N ratio during both periods (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, according to Silva et al.32, this pattern reflects the release of more labile C without accompanying N release due to its recalcitrant bond to the fibrous fraction of the wall cell. The higher C: N ratio observed at the end of the second period compared to the first period could be attributed to the lower N concentration in the roots before incubation in the period 2 (Table 2).

The highest concentration of N in the period 1 (Fig. 4a) can be attributed to the highest N and ADIN concentrations before incubation (Table 2), occurring a greater amplitude of N concentrations between period 1 and period 2, maybe due to the higher precipitation in the end of period 1 than period 2 promoting higher decomposition of label compounds and higher N concentration, mainly recalcitrant compounds as ADIN33, which reflected the highest root concentrations of ADIN during period 1. However, the systems did not affect N concentrations over time and the high soil organic matter may have contributed as a source of N for U0 and reduced the differences between this and the other systems.

Although there was no systems effect on the N input, in study developed in the same area and period, Chaves et al.21 suggested that the intercropping of signal grass and calopo may be recommended for deferment to guarantee the accumulation of forage and crude protein (CP) content equivalent to those of fertilized pastures. In addition, there are the benefits of biological nitrogen fixation and the lower cost of intercropping. According to Depablos et al.34, the biological N fixation of calopo intercropped with marandu grass was 98 kg·ha−1·year−1 at 95% of light interception.

Throughout the incubation period, the reduction in root biomass and stabilization of losses were accompanied by an increase in lignin concentration, especially in period 1 when lignin concentration was slightly higher, which may have contributed to slower biomass decomposition (Fig. 5a and b). According to Zhao et al.33, an increase in the concentration of recalcitrant compounds such as lignin and ADIN likely has a greater impact on the decomposition process than on the C: N ratio, which is widely reported as a determining factor for the decomposition process. The more pronounced increase in the lignin concentration at the beginning of both periods (Fig. 5) can be attributed to the initial loss of biomass owing to the decomposition of labile compounds (Fig. 2).

Several authors have discussed the importance of root chemical composition, especially lignin concentration and the lignin: N ratio, as determining factors for decomposition34,]36. In the present study, a reduction in the lignin: N ratio was observed over time (Fig. 7a), which could be attributed mainly to the increase in N concentration in the incubated roots of all systems, which after 512 days presented an almost three times higher N concentration (Fig. 4a), due to the effect of concentration of recalcitrant nitrogen compounds36formed from the decomposition of labile nitrogen components38,]31.

The increase in ADIN content over time (Fig. 6) was responsible for the reduction in the lignin: ADIN ratio observed in both periods and indicated that although there was an increase in N concentration throughout the decomposition process of roots (Fig. 4a), part of this N was complexed with the fibrous fraction, making access and action of decomposer microorganisms more difficult31.

By evaluating the decomposition of elephant grass roots under different doses of N, Silva et al.24 estimated that 87, 120, and 131 kg·ha−1 of N could be released by roots in the 0–20 cm layer after 512 days of incubation in pastures fertilized with doses of 0, 150, and 300 kg·ha−1·year−1 of N, respectively. These authors reported that different factors may have favored the decomposition and release of N into the soil solution, such as a low lignin: N ratio of the incubated samples, accumulation of nutrients in the soil provided by previous fertilization, and high average temperatures in the Pernambuco State, Brazil.

In the present study, the mineralization of organic material from root litter, despite not having been affected by the cultivation systems, presents a potential average contribution of 18.6 kg·ha−1 of N, after 512 days, in clayey soil and with high MO content. However, even the proportion of calopo remained low over the years (10%), its contribution in terms of N input is value as it can result in reduced cost of chemical fertilizer and a more sustainable cropping system.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Change history

03 April 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95427-7

References

Bogaerts, M. et al. Climate change mitigation through intensified pasture management: estimating greenhouse gas emissions on cattle farms in the Brazilian Amazon. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 1539–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.130 (2017).

Weil, R. R. & Brady, N. C. Soil Organic Matter. In The Nature and Properties of Soils; Weil, R.R., Ed.; Pearson: London, UK, ; pp. 544–600. (2017).

Valle, C. B., Euclides, V. P. B., Simeão, R. M., Barrios, S. C. L. & Jank, L. Gênero Brachiaria. In: (eds Fonseca, D. M. & Martuscello, J. A.) (2 Ed.). Plantas Forrageiras. Viçosa: Editora UFV, 23–76. (2022).

Cardoso, A. S. et al. Pasture management and greenhouse gases emissions. Bioscience J. 38 (e38099), 1981–3163. https://doi.org/10.14393/BJ-v38n0a2022-60614 (2022).

Fan, P. & Guo, D. Slow decomposition of lower order roots: a key mechanism of root carbon and nutrient retention in the soil. Oecologia 163, 509–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-009-1541-4 (2010).

Jing, H. et al. Effect of nitrogen addition on the decomposition and release of compounds from fine roots with different diameters: the importance of initial substrate chemistry. Plant. Soil. 438, 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04017-w (2019).

McCormack, M. L. et al. Redefining fine roots improves Understanding of below-ground contributions to terrestrial biosphere processes. New Phytol. 207 (3), 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13363 (2015).

Beidler, K. V. & Pritchard, S. G. Maintaining connectivity: Understanding the role of root order and mycelial networks in fine root decomposition of Woody plants. Plant. Soil. 420 (1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-017-3393-8 (2017).

Chen, H. et al. Plant species richness negatively affects root decomposition in grasslands. J. Ecol. 105 (1), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12650 (2017a).

Chen, H. et al. Root chemistry and soil fauna, but not soil abiotic conditions explain the effects of plant diversity on root decomposition. Oecologia 185 (3), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-017-3962-9 (2017b).

Castanha, C., Zhu, B., Pries, H., Georgiou, C. E., Torn, M. S. & K., & The effects of heating, rhizosphere, and depth on root litter decomposition are mediated by soil moisture. Biogeochemistry 137 (1–2), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-017-0418-6 (2017).

Xia, M., Talhelm, A. F. & Pregitzer, K. S. Long-term simulated atmospheric nitrogen deposition alters leaf and fine root decomposition. Ecosystems 21 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0130-3 (2018).

Dong, L., Berg, B., Sun, T., Wang, Z. & Han, X. Response of fine root decomposition to different forms of N deposition in a temperate grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 147, 107845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107845 (2020).

Gang, Q. et al. Exogenous and endogenous nitrogen differentially affect the decomposition of fine roots of different diameter classes of Mongolian pine in semi-arid Northeast China. Plant. Soil. 436 (1), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-03910-0 (2019).

Ferreira, T. C. et al. pH effects on nodulation and biological nitrogen fixation in Calopogonium mucunoides. Brazilian J. Bot. 39 (4), 1015–1020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40415-016-0300-0 (2016).

Alencar, N. M. et al. Herbage characteristics of pintoi peanut and Paslisadegrass established as monoculture or mixed Swards. Crop Sci. 58, 2131–2137. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2017.09 (2018).

Baptistella, J. L. C., de Andrade, S. A. L., Favarin, J. L. & Mazzafera, P. Urochloa in tropical agroecosystems. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 4, 119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.00119 (2020).

Bieluczyk, W. et al. Fine root production and decomposition of integrated plants under intensified farming systems in Brazil. Rhizosphere 31, 100930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhisph.2024.100930 (2024).

Inmet. Banco de Dados Meteorológicos do INMET (2021). https://bdmep.inmet.gov.br/

Santos, H. G. et al. Sistema brasileiro de classificação de solos. Brasília, DF: Embrapa, 2018. (2018).

Chaves, C. S. et al. M. Signal Grass Deferred Pastures Fertilized with Nitrogen or Intercropped with Calopo. Agriculture, 11(9), 804. (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11090804

Ribeiro, A. C. Recomendações Para O Uso De Corretivos E Fertilizantes Em Minas Gerais: 5. Aproximação (Comissão de Fertilidade do solo do Estado de Minas Gerais, 1999).

Dubeux, J. C. B. Jr., Sollenberger, L. E., Interrante, S. M. & Vendramini, J. M. B. Litter decomposition and mineralization in Bahiagrass pastures managed at different intensities. Crop Sci. 46 (3), 1305–1310. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2005.08-0263 (2006). Jr.

Silva, H. M. S. et al. Stocking rate and nitrogen fertilization affect root decomposition of elephant grass. Agron. J. 107 (4), 1331–1338. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj14.0618 (2015).

AOAC. Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (Vol. 15thpp. 136–138 (AOAC Official Methods of Analysis, 1990).

Van Soest, P. V., Robertson, J. B. & Lewis, B. A. (1991). Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74 (10), 3583–3597. doi.org/10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2

Littell, R. C., Pendergast, J. & Natarajan, R. (2000). Modelling covariance structure in the analysis of repeated measures data. Stat. Med. 19(13), 1793–1819. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0258(20000715)19:13<1793::AID-SIM482>3.0.CO;2-Q

Fornara, D. A., Flynn, D. & Caruso, T. Effects of nutrient fertilization on root decomposition and carbon accumulation in intensively managed grassland soils. Ecosphere 11 (4), e03103. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3103 (2020).

Kohmann, M. M. et al. Nitrogen fertilization and proportion of legume affect litter decomposition and nutrient return in grass pasture. Crop Sci. 58, 2138–2148. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2018.01.0028 (2018).

Kohmann, M. M., Sollenberger, L. E., Dubeux, J. C. B. Jr., Silveira, M. L. & Moreno, L. S. B. Legume proportion in grass- land litter affects decomposition dynamics and nutrient mineralization. Agron. J. 111, 1079–1089. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2018.09.0603 (2019).

Kohmann, M. M., Silveira, M. L., Brandani, C. B. & Aukema, K. Belowground biomass decomposition is driven by chemical composition in subtropical pastures and native rangelands. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 3 (1), e20076. https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20076 (2020).

Silva, H. M. S., Dubeux Jr, J. C. B., Silveira, M. L., Freitas, E. V., Santos, M. V. F, and Lira, M. A. Stocking rate and nitrogen fertilization affect root decomposition of elephant grass. Agronomy Journal 107 (4), 1331–1338. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj14.0618 (2015).

Silva, H. M. S., Dubeux Jr, J. C. B., Silveira, M. L., Santos, M. V. F., Freitas, E. V., & Lira, M. A. Root decomposition of grazed signal grass in response to stocking and nitrogen fertilization rates. Crop Sci. 59 (2), 811–818. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2018.08.0523 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. Effects of increased summer precipitation and nitrogen addition on root decomposition in a temperate desert. PLoS One. 10 (11), e0142380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142380 (2015).

Depablos, L. et al. Nitrogen cycling in tropical grass-legume pastures managed under canopy light interception. Nutr. Cycl. Agrosyst. 121 (1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-021-10160-7 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Short-term root and leaf decomposition of two dominant plant species in a Siberian tundra. Pedobiologia 65, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2017.08.002 (2017).

Cotrufo, M. F., Wallenstein, M. D., Boot, C. M., Denef, K. & Paul, E. The M icrobial E fficiency-M Atrix S tabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob. Change Biol. 19 (4), 988–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12113 (2013).

Berg, B. & McClaugherty, C. Plant Litter: Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon Sequestration 2nd edn (Springer, 2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq-310110/2022-0), Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Ciência Animal (INCT-CA www.inctca.ufv.br) (Grant Number 465377/2014-9), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES-PROEX-88887.844747/2023-00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.N.C. Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing -review & editing. C.S.C. Investigation, Visualization. A.J.A. Investigation, Visualization. A.J.S.M. Investigation, Visualization. W.S.A. Investigation, Visualization. T.C.S. Investigation, Visualization. O.G.P. Resources, Validation, Visualization. R.B.A.F. Supervision, Validation, Visualization. J.C.B.D.J. Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. K.G.R. Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Results section, under the subheading ‘Root chemical composition before incubation and N accumulation’. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Coutinho, D.N., Chaves, C.S., dos Anjos, A.J. et al. Root decomposition in Urochloa decumbens pastures fertilized with increasing nitrogen doses or intercropped with Calopogonium mucunoides. Sci Rep 15, 6850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91796-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91796-1