Abstract

Super-resolution (SR) techniques present a suitable solution to increase the image resolution acquired using an ultrasound device characterized by a low image resolution. This can be particularly beneficial in low-resource imaging settings. This work surveys advanced SR techniques applied to enhance the resolution and quality of fetal ultrasound images, focusing Dual back-projection based internal learning (DBPISR) technique, which utilizes internal learning for blind super-resolution, as opposed to blind super-resolution generative adversarial network (BSRGAN), real-world enhanced super-resolution generative adversarial network (Real-ESRGAN), swin transformer for image restoration (SwinIR) and SwinIR-Large. The dual back-projection approach enhances SR by iteratively refining downscaling and super-resolution processes through a dual network training method, achieving high accuracy in kernel estimation and image reconstruction. Real-ESRGAN uses synthetic data to simulate complex real-world degradations, incorporating a U-shaped network (U-Net) discriminator to improve training stability and visual performance. BSRGAN addresses the limitations of traditional degradation models by introducing a realistic and comprehensive degradation process involving blur, downsampling, and noise, leading to superior real-world SR performance. Swin models (SwinIR and SwinIR_large) employ a Swin Transformer architecture for image restoration, excelling in capturing long-range dependencies and complex structures, resulting in an outstanding performance in PSNR, SSIM, NIQE, and BRISQUE metrics. The tested images, sourced from five developing countries and often of lower quality, enabled us to show that these approaches can help enhance the quality of the images. Evaluations on fetal ultrasound images reveal that these methods significantly enhance image quality, with DBPISR, Real-ESRGAN, BSRGAN, SwinIR, and SwinIR-Large showing notable improvements in PSNR and SSIM, thereby highlighting their potential for improving the resolution and diagnostic utility of fetal ultrasound images. We evaluated the five aforementioned Super-Resolution models, analyzing their impact on both image quality and classification tasks. Our findings indicate that these techniques hold great potential for enhancing the evaluation of medical images, particularly in development countries. Among the models tested, Real-ESRGAN consistently enhanced both image quality and diagnostic accuracy, even when challenged by limited and variable datasets. This finding was further supported by deploying the ConvNext-base classifier, which demonstrated improved performance when applied to the super-resolved images. Real-ESRGAN’s capacity to enhance image quality, and in turn, classification accuracy, highlights its potential to address the resource constraints often encountered in these settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medical imaging has revolutionized the field of healthcare, providing clinicians with a window into the human body1. Various imaging modalities, such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Computed Tomography (CT), and Ultrasound, have become indispensable tools for diagnosing diseases, guiding treatment, and monitoring patient health. Among these modalities, ultrasound has emerged as a popular choice due to its non-invasive nature, low cost, and real-time imaging capabilities2.

Fetal ultrasound imaging is a crucial diagnostic tool in prenatal care, allowing real-time visualization of fetal development and the early detection of potential abnormalities3. Operating at frequencies between 3-7.5 MHz, these systems provide a non-invasive assessment of fetal anatomy, growth, and well-being. This technique is particularly valuable in developing countries due to its cost-effectiveness and portability4. Key clinical applications of fetal ultrasound include anatomical assessment and anomaly detection, fetal biometry and growth monitoring, placental location and assessment, and multiple pregnancy evaluation. Technical considerations for fetal ultrasound involve transducer frequency selection (typically 3-7.5 MHz), trade-offs between spatial and temporal resolution, acoustic impedance and tissue penetration, and signal processing and image formation5. However, ultrasound imaging, including its application in fetal care, is not without its limitations. The quality of ultrasound images can be affected by factors such as equipment limitations, operator expertise, and fetal position. Specifically in fetal imaging, image quality can be sensitive to maternal tissue characteristics and gestational age. These limitations can compromise the accuracy of diagnoses. More broadly, the quality of ultrasound images can be compromised by various factors, such as the skill level of the operator, the type of equipment used, and the presence of noise and artifacts6. Moreover, the resolution of ultrasound images is often limited by the frequency of the sound waves used, which can result in blurry or incomplete images. This can make it challenging for clinicians to accurately diagnose and treat diseases3.

Traditional image processing techniques, such as those described in7, including Hough transform for feature detection, histogram equalization for contrast enhancement, morphological operations, thresholding techniques, Haar-like feature extraction, and basic filtering methods (like discrete cosine transform and wavelet transform), have been used to improve the quality of medical images. These conventional techniques have served as fundamental tools for enhancing ultrasound image quality and extracting relevant features for fetal monitoring. However, these techniques have limitations in terms of preserving critical details and achieving realistic results. To overcome these limitations, researchers have turned to more advanced techniques, such as Super-resolution (SR).

SR is a new technique that creates sharp, detailed images from blurry or incomplete medical scans. It essentially “enhances” the original image, revealing a clearer view of the body’s internal structures. Traditional SR methods8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 rely on interpolation and other mathematical techniques, but often struggle to preserve critical details and achieve realistic results. In contrast, the advent of Deep Learning (DL) has revolutionized the field of SR. Techniques like DBPISR19, Real-ESRGAN20, BSRGAN21, SwinIR and SwinIR_large22, each wielding its own unique strengths, leverage the power of DL algorithms, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), to generate visually realistic and detailed HR images from blurry or incomplete medical scans.

Recent advancements have marked a turning point in medical imaging visibility, particularly in MRI, CT, and Ultrasound14,23. Images once obscured by blur or noise now reveal intricate details with unprecedented sharpness, providing doctors with a more precise view of the human body’s inner workings. This newfound clarity has revolutionized diagnostic accuracy, enabling more precise treatment plans, meticulous patient progress tracking, and ultimately, a higher standard of care.

The following SR techniques have emerged to address various challenges in medical image enhancement:

-

1.

DBPISR19 utilizes a back-projection approach, iteratively refining high-resolution (HR) images based on low-resolution (LR) input and a learned deep network. This method excels in recovering details from highly degraded images.

-

2.

Real-ESRGAN20 addresses real-world degradations by mimicking complex blur and noise patterns encountered in clinical settings, improving performance on images acquired under diverse conditions.

-

3.

BSRGAN21 tackles “blind” SR, where the degradation model is unknown, employing innovative network architectures and loss functions to reconstruct HR images from LR images with complex distortions.

-

4.

SwinIR22 and SwinIR-Large22 combine Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers, allowing it to model long-range dependencies within images. This unique approach results in improved detail preservation and artifact reduction, creating clearer and more accurate anatomical views.

These innovations are vital for the future of medical imaging across various modalities. Enhanced MRI images reveal intricate anatomical structures, aiding in small lesion detection and facilitating precise quantitative analysis. Ultrasound images gain clarity, revealing subtle tissue structures, improving lesion detection accuracy, and guiding interventions with greater precision. OCT images benefit from sharper detail, allowing better visualization of retinal layers and blood vessels and aiding in early detection and management of retinal diseases. The field of SR in medical imaging continues to evolve, with ongoing research refining algorithms, exploring new applications, and pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. The potential for improving diagnostic accuracy, refining treatment planning, and enhancing patient monitoring is immense, making SR a vital tool in the ongoing quest for better healthcare.

In this paper, we focus on enhancing ultrasound images (US) using advanced image super-resolution techniques, including DBPISR19, Real-ESRGAN20, BSRGAN21, and SwinIR22. Our goal is to evaluate the effectiveness of these techniques in producing high-resolution ultrasonic images. To assess the performance of these techniques, we employ image quality metrics such as Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR)24, Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM)24. These metrics enable us to quantify the improvements in image quality and clarity. To improve image quality assessment, two reference-free metrics, the Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE)25 and the Naturalness Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE)26, have been incorporated. These metrics assess perceptual quality by analyzing spatial features and statistical properties of natural images, offering a quality evaluation that better aligns with human visual perception27,28,29.

The ultimate aim of this research is to determine whether advanced super-resolution techniques can significantly enhance the quality of ultrasound images, thereby transforming the field of medical imaging and diagnostics. Our contributions are as follows:

-

We leverage tow diverse datasets, a Spanish open-source dataset30and a multi-country African dataset31 to evaluate super-resolution techniques on ultrasound images. This approach allows for a comprehensive analysis across different ultrasound devices and image categories, providing insights into the performance of super-resolution models in varied contexts.

-

We apply state-of-the-art super-resolution models, including DBPISR, Real-ESRGAN, BSRGAN, and SwinIR, to enhance ultrasound image quality. These models address common issues such as low contrast and resolution, significantly improving the visual clarity and diagnostic utility of the images.

-

We employ robust image quality metrics, including PSNR, SSIM, BRISQUE and NIQE, to quantitatively assess the improvements achieved by each super-resolution model. This rigorous evaluation provides a clear comparison of model performance and highlights the effectiveness of each approach.

-

We specifically train the DBPISR model on ultrasound datasets using TensorFlow’s Keras API, optimizing performance through techniques like bicubic interpolation and the Adam optimizer. This tailored training enhances the model’s ability to reconstruct high-resolution details from low-resolution inputs.

-

We contrast the internal learning approach of the DBPISR model with the external learning strategies of pre-trained models like Real-ESRGAN, BSRGAN, and SwinIR. This comparison highlights the strengths and limitations of each approach, providing valuable insights into their applicability in different scenarios.

-

We conduct an ablation study using the ConvNext_base classifier to evaluate the preservation of semantic content in super-resolved images. This study provides insights into the maintenance of critical diagnostic features, ensuring that enhanced images retain essential information for accurate diagnosis.

-

We include a device-specific analysis to optimize ultrasound image quality using super-resolution techniques tailored to different ultrasound machines. This analysis aims to improve diagnostic accuracy in resource-constrained settings, offering practical solutions for enhancing medical imaging in diverse environments.

-

We conducted a statistical significance analysis to compare the internal and external learning methods.

-

We reinforced this study by incorporating a Mean Opinion Score (MOS) evaluation conducted by four experienced gynecologists, providing a reliable and expertise-driven measure to assess image quality. This approach ensures that the study integrates domain-specific expertise, offering a robust metric to validate the diagnostic utility of the enhanced ultrasound images, complementing the other metrics employed in our analysis.

This paper is structured as follows: Section “Related works” provides an analysis of the existing literature on this area of study. In section “Materials and methods”, we delineate the materials employed and methods implemented in this investigation. Section “Assessing ultrasound super-resolution quality: a classification-based ablation study” presents a rigorous ablation study conducted to validate the experimental findings. A comprehensive analysis of the results obtained from applying Super-Resolution models across five African geographical regions is presented in Section Experimental results. In the conclusion section, a concise synthesis and critical analysis of the primary contributions delineated within this paper are provided.

Related works

SR techniques have become a cornerstone in medical image processing, particularly for enhancing the quality of ultrasound images32. This section provides a comprehensive review of the application of SR in medical imaging, with a specific focus on ultrasound. We will explore the evolution of these techniques, delve into the development of key deep learning architectures, and critically examine significant studies that have shaped this field. The fundamental aim of SR in medical imaging is to enhance the visibility of intricate anatomical structures, thereby facilitating more accurate diagnoses and improving the precision of measurements. The progression of SR techniques has led to substantial improvements in image quality and the amount of information that can be extracted from ultrasound images, spurring significant research and innovation to fully leverage the potential of SR across diverse medical applications.

Evolution of SR in medical imaging

The application of SR techniques in medical imaging has undergone significant evolution, transitioning from traditional interpolation-based methods to sophisticated deep learning approaches. Early efforts focused on enhancing image resolution through techniques like bicubic interpolation. However, the advent of deep learning marked a transformative phase in medical image enhancement. Researchers worldwide began exploring the potential of deep learning models to significantly improve image resolution. For instance, in the realm of Computed Tomography (CT) imaging, the Efficient Sub-Pixel Convolutional Network (ESPCN)33 demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in upscaling images while maintaining computational efficiency. Similarly, for ultrasound images, the Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Network (SRCNN)34 emerged as a pivotal model. Studies indicated that SRCNN effectively reduces speckle noise, a common artifact in ultrasound imaging, leading to enhanced image clarity and superior visualization of soft tissue structures. Beyond the specific domain of medical imaging, the broader field of computer vision saw the development of influential SR architectures like the Very Deep Super-Resolution Network (VDSR)16 and the Fast Super-Resolution Convolutional Neural Network (FSRCNN)15, which further inspired advancements in medical SR. More recently, the integration of large-scale datasets and computational resources has spurred the adoption of data-driven approaches, such as combining classical signal processing techniques (e.g., wavelet denoising and sparse coding) with deep networks. These hybrid models offer both interpretability and performance, making them especially relevant in clinical environments where explainability is often paramount35.

Fundamental SR architectures

Building upon these early successes, researchers began to explore more complex deep learning architectures tailored for the unique challenges of medical image SR. Van Sloun et al.36 provided a comprehensive overview of how deep learning methodologies could impact various facets of ultrasound imaging. Zhang et al.37 showcased the effectiveness of the Residual Dense Network (RDN) architecture across a range of image restoration tasks, including single image super-resolution, Gaussian image denoising, and artifact reduction, highlighting the versatility of deep residual learning. A significant advancement was the introduction of the Medical Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network (MedSRGAN) by Gu et al.38. This deep learning framework employed a novel generator network to produce high-quality super-resolved medical images from low-resolution inputs. Evaluations on extensive datasets of thoracic CT and brain MRI scans demonstrated the generation of realistic images with preserved fine details, underscoring the potential for improved disease diagnosis and enhanced clinical utility. In addition to CNN-based models, autoencoder architectures have also found applications in medical SR. Autoencoders, when combined with residual connections and attention mechanisms, can learn compact representations of high-resolution features and subsequently generate detailed SR outputs39.

Advanced deep learning applications in medical SR

Further advancements in deep learning for medical SR focused on specific clinical applications, particularly in ultrasound imaging. Several studies targeted the improvement of microvascular imaging. Brown et al.40 introduced SRUSnet, a convolutional neural network architecture designed for the simultaneous detection and localization of contrast microbubbles in ultrasound. Park et al.41 explored the use of deep learning for contrast agent-free Super-Resolution Ultrasound imaging (DL-SRU), enabling the visualization of red blood cells and the reconstruction of blood vessel geometry without the need for contrast agents. Pushing the boundaries of microvasculature visualization, Yi Rang et al.42 presented LOCA-ULM, a method combining deep learning and microbubble simulation to enhance localization performance even under high microbubble concentrations. These endeavors represent a fraction of the diverse and innovative approaches being explored for ultrasound image enhancement through deep learning. Beyond microvasculature, deep learning has demonstrated remarkable potential in enhancing overall image quality across various medical imaging modalities. Hanadi et al.43 investigated the use of super-resolution techniques, particularly Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) like SRGAN44 and Enhanced Super-Resolution GAN (ESRGAN)45, to improve the resolution and detail of MRI images, demonstrating their utility in facilitating more accurate medical diagnoses.

Recent innovations and clinical applications

Recent research has continued to refine SR techniques and expand their clinical applications in medical imaging. Fiorentino et al.4 developed a neural network specifically for fetal ultrasound image processing, aiming to simultaneously improve image quality and resolution. Their review of 153 research articles highlighted the diverse methodologies and applications, including classification, detection, anatomical structure analysis, and biometric parameter estimation. Cammarasana et al.46 proposed a deep learning-based method to enhance the resolution of ultrasound imagery and videos, employing a visual interpolation technique followed by a trained learning model. Their results showed significant improvements in image quality across different anatomical areas and in 2D video super-resolution, holding promise for enhancing clinical practice. The clinical applications of these technologies are vast, spanning from fetal brain imaging to cancer lesion detection and cardiac function evaluation.

Building upon CNN-based architectures, recent works have begun incorporating transformer networks to capture long-range dependencies in medical images. Lu et al.47 presented the ESRT architecture, a hybrid design combining a lightweight convolutional neural network with a lightweight transformer module for enhanced detail and pattern recognition. The model demonstrated comparable reconstruction quality to more computationally intensive approaches with reduced memory usage. Moreover, attention mechanisms-both channel-wise and spatial-have been leveraged to selectively focus on crucial anatomical details, improving the clarity of fine structures often lost in low-resolution ultrasound images48.

Further expanding the applications of deep learning in ultrasound, wavelet-based approaches have gained traction for decomposing ultrasound images into multiple frequency bands, enabling more fine-grained feature extraction. Lyu et al.49 developed WSRGAN, a wavelet-based Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Network for plane-wave ultrasound images, which incorporates wavelet transformations to preserve details often blurred by traditional pixel-based upsampling. This multi-scale strategy helps the network learn both global structures and intricate textures, greatly benefiting microvascular and fetal imaging tasks.

Another emerging trend in medical SR is domain adaptation, particularly for cases where large annotated datasets are scarce or where training and testing distributions differ significantly. Transfer learning and adversarial domain adaptation methods have been adopted to bridge the gap between simulation-based training data and real clinical datasets. For instance, advanced GAN-based domain adaptation frameworks allow a model trained on high-resolution CT or MRI data to be fine-tuned for ultrasound SR tasks50. Such strategies can alleviate the burden of collecting large-scale, high-quality ultrasound data while still achieving competitive performance. The integration of deep learning has significantly propelled the advancement of super-resolution techniques in ultrasound imaging, moving from basic noise reduction models to sophisticated architectures like GANs, CNN-Transformer hybrids, and wavelet-based GANs. Li et al.51 presented a deep learning technique to enhance the detection and localization of thyroid nodules in ultrasound images, demonstrating superior diagnostic accuracy. These innovations have yielded substantial enhancements in image resolution, feature extraction, and diagnostic accuracy across a range of applications, including fetal and microvascular imaging, underscoring their transformative potential for advancing the precision and versatility of ultrasound diagnostics in clinical settings. Additionally, emerging works show the potential of SR in detecting abnormalities like fetal renal anomalies52, further emphasizing how these advancements can improve prenatal diagnostics and outcome predictions. As clinical trials and large-scale validation studies continue, it is expected that SR-enhanced ultrasound imaging will become a standard practice in modern healthcare systems.

By continually refining these approaches and addressing current challenges such as insufficient training data, domain shifts, and the need for interpretability SR methods are poised to transform medical ultrasound into an even more powerful diagnostic modality, with broad implications for patient outcomes and healthcare efficiency.

Materials and methods

Datasets

Spanish dataset The Spanish open-source dataset comprises 1792 patients, and it was collected at The Fetal Medicine Research Centre BC Natal30; it contains over 12400 gray-scale ultrasound (US) images that are divided into 5 categories: abdomen, brain, femur, thorax and others. The three ultrasound devices used here from GE Medical Systems: one Voluson E6, one Voluson S8, one Voluson S10, and one Aloka of Aloka CO. Curved transducers are used with a range of frequency : 3 - 7.5MHz without applying post-processing or artifacts.

African dataset Data were collected from five African countries for this dataset : Algeria, Egypt, and Malawi each contribute 100 images spanning four anatomical categories (abdomen, brain, femur, and thorax). Meanwhile, Ghana and Uganda contribute 75 images each, covering three categories (abdomen, brain, and femur). While both Algeria and Egypt use ultrasound machines from GE Medical Systems, they utilize different devices and probes: Algeria employs a Voluson S8 with a curvilinear transducer, offering a frequency range of 3 to 7.5 MHz. In contrast, Egypt uses a Voluson P8 with a curvilinear transducer fixed at 7 MHz. Malawi used the Mindray DC-N2 US machine with a curvilinear transducer at 3.5 MHz, and the dataset is from Queen Elisabeth Central Hospital. The US machine in Uganda Hospital is Siemens with a curved transducer with a range of frequency of 3 - 7.5 MHz. In the Polyclinic Centre in Accra, Ghana, the ultrasonic imaging system is EDAN DUS 60 US with a curved transducer with a frequency range of 3.5 - 5 MHz. Ultrasound images frequently exhibit suboptimal quality due to low contrast, unclear tissue demarcations, hazy edges, and low resolution. Therefore, we use the appropriate deep learning architecture to enhance the quality of the US image. To rectify these shortcomings, we leverage a suitable deep learning architecture to enhance the quality of ultrasound images.

All the datasets are publicly available, so no approval was necessary for this work.

Medical imaging relies on interpolation techniques53 to resize or resample images without losing crucial information for accurate diagnosis. When working with ultrasound images, the choice of interpolation method is critical for preserving details and ensuring accurate representation. Popular methods include nearest neighbor, bilinear, bicubic, lanczos, and spline interpolation, each offering varying levels of computational complexity and detail preservation. In the first part, we utilized the entire Spanish open-source dataset (12,400 images), which encompasses five image categories: abdomen, brain, femur, thorax, and others. The ”others” category comprises a mixture of fetal images, including the abdomen, brain, femur, and thorax. The processed data is saved for use in the DBPISR model. In summary, the steps are preparing, training, and testing images in the US for a super-resolution task, after calculating image quality metrics, and finally saving the processed data in formats suitable for training the DBPISR model. On the other hand, we evaluated the performance of Real-ESRGAN, BSRGAN, and SwinIR models on all the datasets in this study. These models Real-ESRGAN, BSRGAN, SwinIR, were obtained from the following GitHub repositories: https://github.com/xinntao/Real-ESRGAN; https://github.com/cszn/BSRGAN;https://github.com/JingyunLiang/SwinIR. In what follows, we present the metrics used to measure the quality improvements achieved.

Evaluation metrics

-

PSNR The Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio is widely used as the main metric to evaluate the performance of super-resolution (SR)24. Mathematically, it is defined by the following :

$$\begin{aligned} \text{ PSNR } (I_{\text {LR}}, I_{\text {HR}}) = 10 \cdot \log _{10} \left( \frac{M^2}{ \text {MSE}(I_{\text {LR}}, I_{\text {HR}})} \right) \end{aligned}$$(1)where \(I_{\text {LR}}\) represents the low-resolution image , \(I_{\text {HR}}\) represents the high-resolution image, M is the maximum possible pixel value of a pixel in an image (for 8-bit RGB images, we are used to M=255), and \(\text {MSE} (I_{\text {LR}}, I_{\text {HR}})\) is the mean squared error between images \(I_{\text {LR}}\) and \(I_{\text {HR}}\).

-

Loss Function A loss function is a type of learning strategy used in machine learning to measure prediction error or reconstruction error, and it provides a guide for model optimization24. Over the last few years, a variety of loss functions have been designed to train super-resolution models. One fundamental approach is the Pixel Loss, also known as Mean Squared Error (MSE) or L2 loss, which was implemented in the SRCNN model8. This loss function compares each pixel in the super-resolved (SR) image against its corresponding pixel in the high-resolution (HR) image, calculating the L2 norm of their difference:

$$\begin{aligned} L_{MSE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum _{i=1}^{n} \left\| \textbf{HR}_i - \textbf{SR}_i \right\| _2^2 \end{aligned}$$(2)where n is the total number of pixels, \(\textbf{HR}_i\) represents the i-th pixel in the high-resolution image, and \(\textbf{SR}_i\) represents the corresponding pixel in the super-resolved image. The double vertical bars \(\left\| \cdot \right\| _2\) denote the L2 norm calculation, which measures the Euclidean distance between the pixel values. The L2 loss is particularly effective for optimizing the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), a widely used metric for evaluating model performance. Many state-of-the-art models utilize MSE as their primary learning strategy due to its mathematical properties and optimization characteristics24.

-

SSIM The Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM) provides a complementary evaluation metric that quantifies the structural similarity between the super-resolved image and the high-resolution reference image24. The SSIM is defined as:

$$\begin{aligned} SSIM(x,y) = \frac{(2\mu _x\mu _y + c_1)(2\sigma _{xy} + c_2)}{(\mu _x^2 + \mu _y^2 + c_1)(\sigma _x^2 + \sigma _y^2 + c_2)} \end{aligned}$$(3)where \(\mu _x\) and \(\mu _y\) are the mean intensities, \(\sigma _x^2\) and \(\sigma _y^2\) are the variances, \(\sigma _{xy}\) is the covariance between the images, and \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) are constants to avoid division by zero. A higher SSIM value indicates greater structural similarity between the super-resolved and high-resolution images, suggesting better quality enhancement.

-

BRISQUE The Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE)25 is a no-reference model that quantifies image quality through perceptually relevant spatial features. For ultrasound images, BRISQUE operates by analyzing the normalized luminance coefficients:

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{I}(i,j) = \frac{I(i,j) - \mu (i,j)}{\sigma (i,j) + C} \end{aligned}$$(4)where I(i, j) represents the ultrasound image intensity at position (i, j), \(\mu (i,j)\) is the local mean, \(\sigma (i,j)\) is the local standard deviation, and C is a stability constant. The normalized coefficients are then modeled using a Generalized Gaussian Distribution (GGD):

$$\begin{aligned} f(x;\alpha ,\sigma ^2) = \frac{\alpha }{2\beta \Gamma (1/\alpha )}\exp \left( -\left( \frac{|x|}{\beta }\right) ^\alpha \right) \end{aligned}$$(5)where \(\alpha\) controls the shape of the distribution, \(\beta\) is the scale parameter, and \(\Gamma (\cdot )\) is the gamma function. This model is particularly effective for ultrasound images as it captures both speckle noise characteristics and tissue texture patterns, providing a quality score that correlates well with human visual perception.

-

NIQE The Naturalness Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE)26 assesses image quality without reference images by measuring deviations from statistical regularities observed in natural images. For ultrasound imaging, NIQE constructs a multivariate Gaussian model of image features:

$$\begin{aligned} D(\nu _1, \nu _2) = \sqrt{(\nu _1 - \nu _2)^T \left( \frac{\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2}{2}\right) ^{-1}(\nu _1 - \nu _2)} \end{aligned}$$(6)where \(\nu _1\) and \(\nu _2\) are the mean feature vectors of the natural image model and the test image respectively, and \(\Sigma _1\), \(\Sigma _2\) are their corresponding covariance matrices. This distance metric is particularly relevant for ultrasound images as it captures the natural statistics of tissue patterns and anatomical structures without requiring human-rated distorted images for training. The NIQE score for an ultrasound image is computed as:

$$\begin{aligned} NIQE_{score} = D(\nu _{natural}, \nu _{test}) \end{aligned}$$(7)where \(\nu _{natural}\) represents the feature model learned from high-quality ultrasound images and \(\nu _{test}\) is extracted from the test image. Lower NIQE scores indicate better perceptual quality, with particular sensitivity to the characteristic features of ultrasound imaging such as speckle patterns and tissue boundaries.

Overview of super-resolution strategies

In this work, we explored two main categories of deep learning approaches for Single Image Super-Resolution (SISR): internal learning and external learning. Internal learning, exemplified by the DBPISR model, does not rely on large external datasets; it learns exclusively from the target images (or a small set of similar images). In contrast, external learning approaches (BSRGAN, Real-ESRGAN, and Swin versions) employ models pre-trained on large, diverse image datasets and then fine-tuned or directly applied to our ultrasound (US) data. The following sections detail these models’ architectures, training configurations, and our data preparation protocol.

Training data preparation and configuration

All experiments were conducted using grayscale US images. We extracted patches from these images to form our training and validation sets, enabling the model to learn local details at various scales. Training was performed on an NVIDIA 6000 Ada GPU (48 GB). Table 1 shows our main training setup for DBPISR, representative of the global configuration used throughout our experiments.

Internal learning approach: DBPISR

Dual Back-Projection Based Internal Learning for blind super-resolution (DBPISR)19 reconstructs a High-Resolution (HR) image from a Low-Resolution (LR) input without explicit knowledge of the degradation process. It builds on a dual network structure:

-

1.

A downscaling network that learns to approximate the degradation kernel.

-

2.

A super-resolution network that upscales the LR image back to HR using only internal information from the image itself.

Both networks are jointly trained via a dual back-projection loss, ensuring consistency between the downscaling and upscaling processes. We adapted this architecture for ultrasound images using TensorFlow’s Keras API.

Training procedure

-

Data preparation: We extracted grayscale patches from US images.

-

Compilation: The model was compiled with MSE loss and the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.0003).

-

Iterations: Training was conducted for 3000 iterations to ensure convergence.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall DBPISR structure.

External learning approaches: pre-trained models

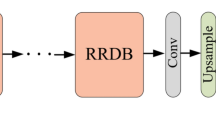

BSRGAN21 is a blind super-resolution model that expands upon ESRGAN45, introducing an improved degradation model to handle more realistic degradations. The generator employs Residual-in-Residual Dense Blocks (RRDB) to extract and refine features before upsampling to HR resolution. A U-Net-based discriminator focuses on differentiating real from generated images, enhancing perceptual quality through adversarial training.

Training procedure:

-

Two-step training:

-

1.

PSNR-oriented training of a baseline BSRNet for high Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio.

-

2.

Perceptual fine-tuning to sharpen results using adversarial and perceptual losses.

-

1.

-

Random degradation model: Blur, noise, and downsampling are applied in random orders to simulate real-world conditions more effectively (Fig. 2).

Real-ESRGAN20 extends ESRGAN45 to tackle complex unknown degradations via a blind super-resolution approach. Its generator also uses RRDB blocks, and a U-Net discriminator is adopted for learning both local details and global structures (Fig. 3). High-order degradations—including multiple stages of blurring, noise addition, resizing, and JPEG compression—are synthesized on-the-fly during training. Training procedure:

-

Blind SR setup: In the absence of high-quality paired data, the model is trained solely on synthetically degraded data.

-

Losses: Adversarial and perceptual losses guide the generator to produce sharp and visually pleasing outputs.

SwinIR54 employs a transformer-based framework for super-resolution, denoising, and deblocking tasks. Unlike purely convolutional approaches, SwinIR uses self-attention mechanisms in both windowed and shifted-window configurations, thereby capturing local and global dependencies within the image. The core components include shallow feature extraction (via a small CNN), deep feature extraction through multiple Residual Swin Transformer Blocks (RSTB), and a final reconstruction stage that merges learned features to generate high-quality outputs. Figure 4 illustrates the general SwinIR structure.

During training, SwinIR can be adapted to various tasks by fine-tuning on domain-specific datasets. A combination of pixel-wise (L1 or L2), perceptual, and/or adversarial losses is commonly employed to balance fidelity and perceptual realism.

SwinIR-M (Middle Size) is typically trained on a moderately sized dataset suite, including DIV2K (800 images), Flickr2K (2,650 images), and OST (10,324 images covering sky, water, grass, mountain, building, plant, and animals). This variant is efficient in terms of computational cost while still performing robustly on most standard super-resolution tasks.

Real-ESRGAN architecture20.

SwinIR-L (Large Size) extends the training corpus to include WED (4,744 images), FFHQ (first 2,000 face images), Manga109 (manga/anime content), and SCUT-CTW1500 (first 100 training images containing text). This larger-scale dataset enables the model to capture a broader range of real-world degradations and content types, generally resulting in superior performance for diverse and challenging inputs. However, this improvement in image quality and generalization usually comes at the cost of increased computational requirements (larger model capacity and more training iterations).

Assessing ultrasound super-resolution quality: a classification-based ablation study

The objective assessment of the quality of images reconstructed by super-resolution models is often based on metrics such as PSNR and SSIM. Despite their utility in assessing image quality, those metrics may not completely represent the fidelity of reconstructed content. Therefore, this ablation study investigates the use of a high-performance image classifier as a complementary indicator of reconstruction quality.

We suppose that a successful Super-Resolution reconstruction should preserve the visual information required for a classifier to reach comparable or even better accuracy than that obtained on the original image. We also remark that a good image reconstruction, carried out by a Super-Resolution model, is not limited to a simple improvement in resolution or sharpness. Successful classification relies upon the preservation of key visual features that distinguish the primary object within an image. These discriminative characteristics are important during classification since they allow one object to be distinguished from another. To validate this hypothesis, we will apply a classifier to images reconstructed by the enhancement models used previously. By comparing the classification metrics achieved on the original and reconstructed images, we will be able to estimate the effectiveness with which Super-Resolution preserves the semantic information crucial for object recognition. This analysis will determine the correlation between image metrics (PSNR, SSIM, BRISQUE, NIQE) and the preservation of semantic content as assessed by classification performance. To elaborate this strategy, we employed the ConvNext_base classifier because of its high-quality performance compared to other classifiers.

ConvNeXt_base classifier

Inspired by Vision Transformers, ConvNeXt, a pure convolutional architecture introduced in “A ConvNet for the 2020s”55, uses a hierarchical, pyramid-like structure to obtain competitive results on diverse Computer Vision tasks with notable simplicity and computational performance. ConvNeXt_base55has established itself in the scientific literature as a powerful convolutional neural network architecture. In constructing the architecture of ConvNext_base, the authors were inspired by advances in Vision Transformers (ViT) while remaining faithful to the simplicity and efficiency of classic Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). So they have subtly combined optimized convolutional blocks and judicious architectural choices.

SwinIR architecture54.

-

Hierarchical feature extraction: The first step consists of hierarchical feature extraction: First, the input image is processed by an initial convolutional layer called (stem), reducing its resolution while increasing the number of channels. Afterwards, it is followed by a series of three “stages”, composed of repeated ConvNeXt blocks. A pyramidal representation is formed by successively downsampling spatial resolution and increasing channel depth at each stage. In each ConvNeXt block, there is a high-dimensional (7x7) depthwise convolution capable of capturing extensive spatial dependencies while remaining parameter efficient. Layer normalization, channel expansion/reduction, non-linear activation function (GELU), and residual connection mechanisms enrich these blocks, thus optimizing the learning of discriminative representations.

-

Global aggregation: The next step is global aggregation, where the image is described by a rich and abstract feature map. A “global average pooling” procedure is then employed to synthesize the global information of this map into a single vector. The extracted feature vector gives a compact representation suitable for input to the final classification layer.

-

Classification: The final step is classification: The vector resulting from the global aggregation is passed to a classifier, which consists of one or more fully connected layers. The classifier, constituted by one or more fully connected layers, applies to the input vector a probability of belonging to each class. The final layer is composed of one neuron per class, each outputting a score directly considered as the predicted probability of the corresponding class.

In summary, ConvNeXt_base analyzed the image with a hierarchy, extracting features at different scales in order to have an abstract and global representation. On the basis of the provided feature vector, the classifier predicts then the class of the image. Its architecture is presented in Fig. 5.

Experimental results

Having established the architecture and functionality of the ConvNext_base classifier, we now present the experimental results, including the performance metrics of the SR models and the corresponding classification outcomes obtained using the aforementioned classifier.

-

Quantitative and qualitative assessment of super-resolution techniques: We apply the models to our datasets and assess their performance using these metrics: PSNR and SSIM. In the first part, we utilized the entire Spanish open-source dataset (12,400 images), which encompasses five image categories: abdomen, brain, femur, thorax, and others. In the latter part, datasets from Algeria, Egypt, and Malawi contain four ultrasound image classes: abdomen, brain, femur, and thorax. Additionally, datasets from two African countries, Ghana and Uganda, include ultrasound images categorized into three groups: abdomen, brain, and femur. Each category across all African databases comprises 25 ultrasound images. The processed data is saved for use in the DBPISR model. In summary, the steps are preparing, training, and testing images the US for a super-resolution task, after calculating image quality metrics, and finally saving the processed data in formats suitable for training the DBPISR model. The DBPISR model utilized the bicubic interpolation technique, resulting in more than satisfactory outcomes on our databases. Following that, we evaluated samples from only four datasets for the other models. For that, We used pre-trained super-resolution models : REAL-ESRGAN20, BSRGAN21, SwinIR54 Table 2 presents these image quality measures for each model.

We utilize also Objective No-Reference Image Quality Assessment Metrics such as NIQE56 and BRISQUE56 to evaluate the quality of images without the need for a reference image. BRISQUE or Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator is an objective, no-reference metric for assessing image quality without the need for a pristine reference image. It functions by analyzing spatial natural scene statistics to detect and quantify distortions and deviations from the normative patterns of undistorted natural images. Elevated BRISQUE scores correspond to increased levels of degradation and diminished perceived image quality. The second metric called NIQE quantifies how much an image deviates from the statistical characteristics of natural images. Consequently, a higher NIQE score indicates a greater level of degradation and lower image quality. All measures are illustrated in Table 3.

For each anatomical region of the fetus, we generate a dataset of original images(First on the left) and upsampled images to 4X resolution (namely, DBPISR, BSRGAN, Real-ESRGAN, SwinIR, and SwinIR_large) and present the corresponding Fig. 6.

ConvNeXt 55: (a) ConvNeXt architecture; (b) ConvNeXt block; (c) down-sampling.

To emphasize the detail captured by each super-resolution model used in our study, Fig. 7 presents close-up views of femur ultrasound images, focusing on the various details within the enhanced images. Comparing these close-ups allows for a visual analysis of how each model enhances specific aspects of the images.

-

Classification performance evaluation The essential task of accurately evaluating Super-Resolution models classification performance was undertaken using three metrics. These metrics are detailed below. Accuracy57,58 measures correct predictions over total predictions. F1-score58, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a robust metric for imbalanced datasets. Kappa59 assesses agreement between predicted and true labels, correcting for chance. According to this study59, higher values for all three indicate better performance. The SR models were classified according to the protocol outlined in Table 4. In the training process, we applied the following augmentation techniques:

-

RandomHorizontalFlip: Randomly flips the image horizontally with a probability of 50%. This helps the model generalize better to symmetries in the dataset.

-

RandomVerticalFlip: Randomly flips the image vertically with a probability of 50%. Similar to horizontal flipping, this helps in learning invariance to the orientation of the images.

-

RandomRotation: Rotates the image by a random angle within a range of ±20 degrees. This simulates real-world variations in image capture angles, improving the model’s ability to handle rotational variances.

-

ColorJitter: Adjusts brightness, contrast, and hue by random factors up to ±50%. This augmentation simulates variations in lighting conditions and color differences that may arise in different imaging devices or environments.

-

To measure the impact of super-resolution, we compared classification results based on original and enhanced images (generated by five super-resolution models) across datasets from Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Malawi, Spain, and Uganda. Results are presented in Tables 5 (Spain) and 6 (Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda).

Discussion

First, we discuss the results of the Super-Resolution models utilized for analyzing ultrasound images across different countries in (A.), and then the classification results are examined in (B.).

-

A.

Super-Resolution Enhancement: Analytical Interpretation and Evaluation

-

Ultrasound imaging technology: a comparative overview Before, we noted that Consistency column in Tables 7 and 8, is based on a statistical analysis (percentile calculation, standard deviation computation, and mean difference calculation) of the models’ performance results, with the terms “High,” “Good,” “Moderate,” and “Average” reflecting the observed variability in performance. A model classified as “High” exhibits low variability, producing highly stable outputs. A “Good” model demonstrates moderate variability, offering generally consistent performance with slight fluctuations. A “Moderate” model shows greater variability compared to “Good,” while an “Average” model is characterized by high variability, with larger deviations in its performance.

-

(a)

Algeria and Egypt:

-

(a)

-

In the Algerian case, and according to Tables 3, 7 and Fig. 8, the evaluation of Super-Resolution model performance highlights notable differences across the various approaches. After recalculating the PSNR and SSIM metrics for the studied models, the SSIM of BSRGAN remained unchanged and it is still emerges as the most effective, demonstrating superior performance across both precision and perceptual quality metrics. With the highest PSNR (35.21 dB) and SSIM (0.882), coupled with exceptional perceptual quality scores (NIQE: 8.98 ± 6.06 and BRISQUE: 44.28 ± 5.17), BSRGAN consistently delivers visually sharp and reliable outputs. These results, detailed in Table 3, underscore its robust capability to minimize variability while maintaining high visual fidelity, making it the optimal model for application in the Algerian context. Ranked second, Real-ESRGAN achieves a median PSNR of 33.63 dB and a SSIM of 0.847. Although it falls slightly short of BSRGAN in terms of precision, its perceptual quality metrics (NIQE: 12.73 ± 8.01, BRISQUE: 63.69 ± 6.68) remain competitive. This combination of visual stability and acceptable overall performance positions Real-ESRGAN as a reliable alternative for applications that demand robust and consistent results. However, the SSIM of SwinIR_Large model has decreased from 0,88 to 0.852 and its PSNR is now 34.27 dB. Albeit effective in certain tasks, SwinIR_Large is constrained by its weaker perceptual quality metrics (NIQE: 29.08 ± 23.24, BRISQUE: 59.91 ± 7.93). Furthermore, the presence of prominent outliers in the SSIM distribution, as shown in the boxplot in Fig. 8d, is noteworthy. These outliers indicate challenges in consistently reconstructing certain images with high structural fidelity. When coupled with the significant variability in NIQE scores, these limitations reduce the model’s reliability for applications that demand consistent and high-quality visual reconstruction. SwinIR exhibits comparatively weaker performance, as reflected by its perceptual quality metrics (NIQE: 29.81 ± 18.10 and BRISQUE: 65.09 ± 9.94). Furthermore, its lower PSNR (33.48 dB) and SSIM (0.839), combined with considerable variability, underscore its limitations. These shortcomings make SwinIR less suitable for applications that require consistent and high-quality image reconstruction. DBPISR ranks at the bottom of the evaluation, demonstrating the weakest overall performance. While it achieves a PSNR of 28.18 dB and a SSIM of 0.836, its perceptual quality metrics (NIQE: 19.62 ± 5.65, BRISQUE: 84.74 ± 17.95) reveal a high incidence of visual artifacts and suboptimal reconstruction quality, further emphasizing its limitations in delivering reliable outputs.

In the Egyptian context, the performance of Real-ESRGAN on the ultrasound device, using a 7 MHz transducer, was particularly noteworthy. As shown in Tables 3, 8 and Fig. 8b, Real-ESRGAN stands out as the top-performing model in the evaluation, achieving the highest PSNR (35.40 dB) and SSIM (0.909), indicative of exceptional fidelity and strong structural alignment. The model exhibits remarkable consistency, ensuring stable and reliable outcomes across various scenarios. Its ability to produce sharp details and achieve the lowest NIQE score (56.24 ± 4.32) highlights its capability to deliver realistic and visually pleasing reconstructions. Furthermore, the model achieves the lowest BRISQUE score (3.78 ± 2.20), underscoring its superior perceived image quality. While it occasionally accentuates graininess, this minor drawback is outweighed by its overall performance advantages. These attributes position RealESRGAN as the most suitable choice for high-quality image restoration tasks, particularly in contexts where fidelity and realism are critical. BSRGAN demonstrates robust performance with a PSNR of 33.98 dB and an SSIM of 0.856, slightly lower than Real-ESRGAN but still indicative of high-quality output. The model maintains good consistency, ensuring reliable results across different inputs. It excels in producing sharp images with a relatively low NIQE score (68.69 ± 6.74), although this score is higher than that of Real-ESRGAN, suggesting a marginally less realistic appearance. The BRISQUE score of 7.67 ± 4.06 remains commendable, albeit slightly inferior to Real-ESRGAN, indicating a good but slightly diminished perceived image quality. Minor artifacts may be present, but their impact on the model’s overall performance is negligible. These characteristics establish BSRGAN as a reliable model for generating sharp and visually pleasing images, making it a strong alternative, albeit with slightly lower perceived quality compared to Real-ESRGAN. SwinIR_Large demonstrates moderate performance, achieving a PSNR of 32.73 dB and an SSIM of 0.773, reflecting reasonable but not exceptional image fidelity. The model exhibits average consistency, with noticeable variability in output quality. While the SSIM is acceptable and the NIQE score of 42.99 ± 6.55 is lower than that of BSRGAN, it remains relatively high, suggesting room for improvement in perceived image realism. The BRISQUE score of 38.59 ± 28.62 further highlights this variability, indicating inconsistent perceived quality across different outputs. This variability in performance may present challenges for applications requiring consistent and high-quality image restoration, limiting the model’s suitability for such use cases. SwinIR shows lower performance compared to other models, with a PSNR of 31.51 dB and an SSIM of 0.717, reflecting reduced fidelity and structural accuracy. While it is efficient in processing, this comes at the expense of output quality, as indicated by its high BRISQUE (51.41 ± 29.60) and NIQE (49.82 ± 8.98) scores, which highlight subpar perceived quality and less realistic reconstructions. DBPISR exhibits notably poor performance, with a PSNR of 24.10 dB and an SSIM of 0.647, reflecting low fidelity and structural accuracy. The model shows high variability in output and limited realism, as indicated by its high NIQE score (68.69 ± 6.74). While its BRISQUE score (19.50 ± 4.58) is better than SwinIR’s, it remains inferior to Real-ESRGAN and BSRGAN, underscoring its mediocre perceived quality. These shortcomings render DBPISR unsuitable for applications requiring high-quality image reconstruction. The outcomes of the improvement models applied in Algeria and Egypt with their ultrasound equipment have presented significant differences that may affect the choice of the Super-Resolution model depending on the clinical context and the material constraints of the devices employed in these countries.

-

(b)

In Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda: The models were evaluated using established image quality metrics, including NIQE, BRISQUE, PSNR, and SSIM. Notably, lower NIQE and BRISQUE scores correlate with superior perceptual quality and a more natural appearance, as shown in Table 3 and in Table 9.

Within the Ghanaian context, an exhaustive evaluation was undertaken encompassing five Super-Resolution (SR) models: BSRGAN, Real-ESRGAN, DBPISR, SwinIR, and SwinIR_Large. Among these, BSRGAN and Real-ESRGAN distinguished themselves as the foremost performers, exhibiting superior efficacy in augmenting image quality. Both BSRGAN and Real-ESRGAN demonstrate comparable performance metrics concerning the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), with each model attaining a value of 0.91. However, BSRGAN exhibits a marginally enhanced Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), registering 38 dB in contrast to 37.8 dB achieved by Real-ESRGAN. Consequently, the selection between these models hinges on the relative prioritization of detail fidelity (PSNR) versus structural congruence (SSIM). In the realm of perceived image quality metrics, Real-ESRGAN records a lower Naturalness Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) score of 1.34, indicative of a heightened natural appearance in the generated imagery. In stark contrast, BSRGAN secures a more favorable Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE) score of 44.15, thereby signifying a superior overall perceived image quality when juxtaposed with Real-ESRGAN’s score of 59.74. Furthermore, the remaining models-DBPISR, SwinIR, and SwinIR_Large-exhibit markedly elevated NIQE and BRISQUE scores, underscoring their relatively inferior perceived quality. In the Malawian context, an extensive evaluation was conducted encompassing five Super-Resolution (SR) models: BSRGAN, Real-ESRGAN, DBPISR, SwinIR, and SwinIR_Large. Among these, BSRGAN and Real-ESRGAN emerged as the foremost performers, demonstrating superior efficacy in enhancing image quality with an SSIM value equals to 0.84. Though BSRGAN demonstrated a marginally superior Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) of 34.6 dB compared to 33.9 dB for Real-ESRGAN. Regarding perceived image quality, BSRGAN achieved lower Naturalness Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) and Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE) scores of 6.42 and 41.63, respectively, compared to Real-ESRGAN’s 6.73 and 59.42. The remaining models like DBPISR, SwinIR, and SwinIR_Large exhibited significantly higher NIQE and BRISQUE scores, indicating inferior perceived quality. Consequently, similar to findings in the Ghanaian case , the selection between BSRGAN and Real-ESRGAN for medical imaging applications in Malawi should be guided by specific priorities, favoring BSRGAN for overall image quality or Real-ESRGAN for improved naturalness. In Uganda, among five Super-Resolution models, BSRGAN and Real-ESRGAN demonstrated superior performance with identical SSIM scores of 0.92. BSRGAN slightly outperformed Real-ESRGAN in PSNR (35.9 dB vs. 35.5 dB) and achieved better overall perceived quality through lower BRISQUE scores (43.20 vs. 63.10). Conversely, Real-ESRGAN exhibited enhanced naturalness with a superior NIQE score (3.69 vs. 3.95). DBPISR, SwinIR, and SwinIR_Large recorded significantly higher NIQE and BRISQUE scores, indicating inferior perceived quality. To summarize, Real-ESRGAN is favored in both Ghana and Uganda for its superior naturalness, as indicated by lower NIQE scores, whereas BSRGAN is preferred for its enhanced overall image quality, demonstrated by better BRISQUE scores. In Malawian context, BSRGAN markedly surpasses Real-ESRGAN in both PSNR and perceived quality metrics, making it the optimal choice for high-fidelity medical imaging. Other models, including DBPISR and SwinIR, exhibit significantly inferior performance in both fidelity and perceived quality. Consequently, BSRGAN is recommended for applications prioritizing comprehensive image quality, while Real-ESRGAN is suitable when image naturalness is paramount.

Figure 9 shows the box plots of the statistics of the PSNR,SSIM and BRISQUE metrics for the three ultrasound machines utilized in Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda, respectively.

The objective of this statistical test is to select the optimal SR model from the five SR models : then, we verified the statistical significance of all SR models used in this study, by analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 0.05 level of significance, and we obtained scatter plots in Figs. 10 and 11 that visualizing as the relationship between SSIM and PSNR, analyzed to assess the performance of SR models trained on ultrasound images, comparing the efficacy of internal and external training datasets.

PSNR, SSIM and (PSNR/BRISQUE) box-plots of the five SR models: (a) BSRGAN, (b) real-ESRGAN, (c) swin, (d) Swin_large and (e) DBPISR. These box plots show the PSNR/SSIM statistics calculated on a set of 75,100 and 75 images resp. for: Ghana, Malawi and Uganda; the enhancement of these networks is 4X.

We noted:

-

A strong positive correlation between (PSNR, SSIM) and (PSNR, BRISQUE) is consistently observed across all plots, indicating that higher signal fidelity generally corresponds with improved structural preservation in the enhanced images.

-

Externally trained SR models consistently outperform their internally trained counterparts, achieving higher PSNR and SSIM values. This underscores the critical role of diverse, external training data in developing robust Super-Resolution models capable of achieving superior reconstruction quality. However, performance variations are observed among the externally trained models, highlighting that model architecture and the specific training data utilized significantly influence a model’s effectiveness.

Optimal Super-Resolution model selection depends on the specific image characteristics of each ultrasound system employed in these developing countries.

In order to further explore the implications of the statistical analysis done in (A.), we will interpret the results obtained during the classification of the original images and the super-resolved images of the five SR models.

-

B.

Classification results: analysis and evaluation

-

Spanish dataset: The Table 10 below compares the performances obtained when we carried out the classification of the original ultrasound images and those reconstructed by the Super-Resolution models. To assess the effect of using it, we evaluated performance using three established metrics: Accuracy, F1 Score, and Kappa.

-

For the initial model (DBPISR), performance metrics revealed improvements as follows: accuracy increased by 1.00%, the F1-score by 1.15%, and the kappa statistic enhanced by 1.38%. The SwinIR model shows comparable increases: accuracy (+1.09%), F1-score (+1.14%), and Kappa (+2.25%), suggesting greater classification robustness. However, the BSRGAN model demonstrates no measurable advantage for image classification in this context. The Real-ESRGAN model does a slightly better performance than DBPISR, increasing accuracy by 1.18%, F1-score by 1.53%, and Kappa by 1.60%. Interestingly, while the SwinIR_large model doesn’t change accuracy, it increases F1-score by 1.18% and Kappa by 1.67%.

We observe that Real-ESRGAN leads accuracy improvements (+1.18%) followed by DBPISR (+1.00%) and SwinIR (+1.09%), while SwinIR_large showed negligible gains (<0.1%). Real-ESRGAN also topped F1-score improvement (+1.53%), with DBPISR, SwinIR, and SwinIR_large showing similar increases ( 1.15%). However, SwinIR significantly improved Cohen’s Kappa (+2.25%), suggesting superior error reduction, followed by SwinIR_large (+1.67%) and Real-ESRGAN (+1.60%). These Kappa improvements confirm performance gains beyond chance.

-

African datasets Table 6 reports the performance of five SR models for classifying ultrasound images from African countries (Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Malawi and Uganda) using the three same metrics: accuracy, F1-score, and Kappa coefficient. The models’ performances, compared to the results obtained with the original images, are presented in Table 11.

Super-resolution (SR) model performance varied substantially across datasets from Algeria, Egypt, Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda:

BSRGAN consistently underperformed: Negative impacts were most pronounced in Uganda (0% accuracy, -5.08% F1, -13.95% Kappa) and Egypt (-11%, -9.3%, -4.03%), with minor negative effects observed in Ghana and Malawi. Performance remained neutral in Algeria.

DBPISR presented the most inconsistent performance: While highly effective in Ghana (+42.67%, +30.71%, +31.14%) and Uganda (+34.67%, +12.63%, +17.21%), it exhibited substantial degradation in Algeria (negative changes across all metrics) and Malawi (-9%, -19.73%, -30.6%). In Egypt, it yielded increased accuracy and F1-score but decreased Kappa, indicating inconsistent prediction agreement.

Real-ESRGAN consistently demonstrated strong performance: In Algeria, it yielded significant improvements across all metrics (+11% accuracy, +5.57% F1-score, +11.66% Kappa). Similar positive trends were observed in Egypt (+6% accuracy, +3.44% F1, +2.17% Kappa), Ghana (+13.34%, +14.51%, +14.14% respectively), and Malawi (+13%, +6.54%, +8.2% respectively). However, its impact in Uganda was negligible.

SwinIR exhibited a mixed performance profile: While demonstrating positive gains in Algeria, though less pronounced than Real-ESRGAN, it yielded modest improvements in Egypt (+2%, +0.92%, +1.76% for accuracy, F1 score, and Kappa respectively) and Ghana (+6.67%, +8.07%, +4.49%), and negligible impact in Uganda. Notably, it showed robust performance in Malawi (+18%, +10.15%, +12.2%).

SwinIR_large generally struggled, exhibiting negligible or negative impacts across Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda. Performance was neutral in Algeria. In Egypt, despite a Kappa increase (+4.27%), minimal gains in accuracy and F1-score suggested limited overall benefit.

These variations underscore the complex interplay between model architectures and dataset characteristics.

By cross-referencing the image quality data (PSNR, SSIM) with classification performance, we can draw the following findings: Real-ESRGAN offers a balanced combination of good image quality (PSNR and SSIM) and strong classification performance in almost all countries, except in Uganda, where its improvements are more neutral. Nevertheless, it remains the most suitable model across the five countries overall. BSRGAN shows good image quality, with the highest (PSNR and SSIM) scores in several regions (notably in Uganda), but it fails to translate this quality into better classification performance. This suggests an inefficiency in generalizing to the classification task. SwinIR exhibits lower image quality, but its classification performance, especially in Malawi, demonstrates that it can compensate for inferior image quality through better adaptation to the classification data. DBPISR has very low PSNR scores, which directly correlates with its poor classification performance in almost all countries, except Uganda and Ghana. We evaluated the performance of five super-resolution (SR) models, DBPISR, BSRGAN, Real-ESRGAN, SwinIR, and SwinIR_large, for enhancing ultrasound image quality in various African contexts. Evaluation is based on five metrics: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Structural Similarity Index Measure, then classification metrics as Accuracy, F1 score, and Kappa coefficient ( See Fig. 12). Real-ESRGAN consistently outperformed other super-resolution models, demonstrating robustness and high-quality reconstruction even in settings with equipment limitations common in Africa. SwinIR, including SwinIR_large, excelled in settings with higher-quality equipment (Algeria and Malawi), demonstrating its suitability for environments with fewer hardware limitations. DBPISR consistently underperformed, proving unsuitable for widespread use in the evaluated African contexts.

Key observations: evaluating model performance by metric

-

PSNR: BSRGAN and Real-ESRGAN exhibited high PSNR values, signifying good reconstruction quality and minimal noise. DBPISR consistently demonstrated low PSNR, particularly in Egypt, suggesting inferior image quality.

-

SSIM: Real-ESRGAN consistently achieved high SSIM scores (> 0.9), indicating excellent reconstruction fidelity. SwinIR_large and BSRGAN also performed well, particularly in Algeria and Ghana.

-

NIQE : Real-ESRGAN achieved the lowest NIQE scores, reflecting the highest image naturalness, particularly in Ghana (1.34) and Uganda (3.69). DBPISR consistently yielded the highest NIQE scores, indicating significant artifacts and reduced image quality, with Algeria (19.62) being the most affected. BSRGAN demonstrated competitive NIQE performance in Malawi (6.42) and Uganda (3.95), maintaining reasonable naturalness.

-

BRISQUE : BSRGAN consistently exhibited low BRISQUE scores, particularly in Algeria (44.28) and Uganda (43.20), underscoring its superior perceptual quality. DBPISR recorded the highest BRISQUE scores, notably in Ghana (89.84), indicating the poorest perceptual image quality. Real-ESRGAN displayed moderate BRISQUE performance, with its best results observed in Egypt (56.24).

-

Accuracy: Real-ESRGAN achieved near-perfect accuracy in Algeria and remained a top performer in Malawi. All models struggled in Ghana, suggesting data-related challenges. DBPISR exhibited the lowest accuracy across all countries, with Ghana (48%) and Malawi (57%). BSRGAN and SwinIR performed well in Algeria but failed to generalize effectively in Ghana and Uganda.

-

F1 score: Real-ESRGAN and SwinIR excelled in Algeria and Malawi. Ghana posed challenges for all models, suggesting data-specific limitations.

-

Kappa coefficient: Real-ESRGAN achieved the highest Kappa values, particularly in Algeria (92.33%) and Malawi (71%), indicating reliable classification performance. SwinIR and SwinIR_large followed while DBPISR performed poorly, particularly in Egypt.

-

C.

Medical expert evaluation: MOS for assessing SR model quality: In our study, experienced gynecologists evaluated the visual quality and diagnostic utility of ultrasound images enhanced by five super-resolution (SR) models-BSRGAN, DBPISR, SwinIR, SwinIR_Large, and Real-ESRGAN-alongside the original ultrasound images through a form that contains a set of questions, as illustrated in Fig. 13. The assessment focused essentially on critical criteria, including contour sharpness, fine detail visibility, noise reduction, absence of artifacts, and overall diagnostic relevance and an evaluation of “diagnostic confidence” based on three key questions: ”Does the image quality allow for clear identification of anatomical structures? Does this image enhance your confidence in the diagnosis? Are there any features in the image that might contribute to a potential misdiagnosis?” This Mean Opinion Score (MOS) was assessed on a five-point scale: 1 represents poor quality, and 5 reflects exceptional quality. Diagnostic confidence was also assessed, emphasizing the clarity of anatomical structures and the potential of enhanced images to improve diagnostic certainty. Evaluators highlighted cases where artifacts or inconsistencies could lead to misinterpretation. These findings connect computational performance metrics with real-world clinical applicability, offering valuable insights into the strengths and limitations of SR models in medical imaging. A statistical analysis was conducted to assess the performance of various image enhancement methods using descriptive measures. Specifically, the following were calculated: The mean to evaluate the overall performance of each method. The standard deviation to measure the variability of the results for each method. The median and quartiles to examine the distribution of scores and identify the central tendency of the data, particularly when extreme values may influence the results. By applying these methods, the stability and performance of each image enhancement technique were compared, providing a comprehensive overview of the diagnostic results. With the first doctor in Fig. 13, SwinIR illustred the highest performance with a score of 3.6, slightly outperforming SwinIR_LARGE at 3.4 and BSRGAN at 3.2. The Real-ESRGAN model achieved the highest score of 4.0, presenting a notable difference of 0.8 from BSRGAN. DBPISR performed similarly to SwinIR, both scoring 3.6, with a 0.4 difference from BSRGAN. The differences between SwinIR and BSRGAN, SwinIR_LARGE and BSRGAN, and DBPISR and BSRGAN were relatively small, ranging from 0.2 to 0.4. For Doctor Nº2, SwinIR scored 3.5, outperforming SwinIR_LARGE at 3.2 and BSRGAN at 2.6. Real-ESRGAN achieved the highest score of 4.1, showing a significant difference of 1.5 from BSRGAN. DBPISR performed better than BSRGAN, with a score of 3.7, showing a 1.1-point difference. The differences between SwinIR and BSRGAN, SwinIR_LARGE and BSRGAN, and DBPISR and BSRGAN were more pronounced, ranging from 0.6 to 1.5. For Doctor Nº3 in Fig. 13c , SwinIR scored 3.8, surpassing SwinIR_LARGE at 3.5 and BSRGAN at 2.9. Real-ESRGAN achieved the highest score of 4.2, with a notable difference of 1.3 from BSRGAN. DBPISR performed similarly to SwinIR, both scoring 3.8, with a 0.9-point difference from BSRGAN. The differences between SwinIR and BSRGAN, SwinIR_LARGE and BSRGAN, and DBPISR and BSRGAN ranged from 0.6 to 1.3. In Fig. 13d, SwinIR achieved a score of 4.2, exceeding both SwinIR_LARGE (3.8) and BSRGAN (3.6). Real-ESRGAN achieved the highest score of 4.3, surpassing BSRGAN by 0.7 points. DBPISR scored 4.0, showing a 0.4-point difference from BSRGAN. The differences between SwinIR, SwinIR_LARGE, DBPISR, and BSRGAN were generally minor, ranging from 0.2 to 0.7. These results indicate that, while image enhancement models effectively fulfill their initial objectives ( as enhancing face or natural images ), their performance can vary significantly when applied to ultrasound images. Such images, often characterized by artifacts like speckle noise, pose complex challenges for these models. Furthermore, SwinIR surpassed other super-resolution models in performance. Real-ESRGAN ranks last, alongside the DBPISR model. However, the models considered most competitive, according to medical experts, are SwinIR_LARGE and BSRGAN, following SwinIR model.

Clinical implications and real-world applications

Our findings suggest that SR has significant potential to enhance both clinical decision-making and patient outcomes in resource-constrained and mainstream hospital settings:

Clinical impact in low-resource settings. One of the most pressing challenges in developing countries is the limited availability of high-end ultrasound devices. By improving image resolution and reducing noise, SR models facilitate clearer visualization of fetal anatomy, enabling the detection of subtle anomalies that might otherwise remain unidentified. This is crucial where mid-range or outdated ultrasound equipment often lacks the resolution required for detailed fetal assessment. Consequently, implementing SR can help address care disparities and improve diagnostic confidence in prenatal screening.

Operator independence and workflow enhancement. Ultrasound imaging commonly depends on the operator’s expertise. SR offers a partial mitigation strategy by enhancing suboptimal images, thereby reducing the impact of operator-dependent variability on diagnostic accuracy. This democratization of ultrasound quality can be especially beneficial for clinicians or radiology technicians in the early stages of training or in settings with constrained human resources. Furthermore, routine clinical workflows can be preserved by integrating SR algorithms as a post-processing step or via embedded devices that generate enhanced scans in near-real time.

Practical deployment and telemedicine. Beyond laboratory settings, the ability to deploy SR models on embedded AI platforms (e.g., Raspberry Pi, NVIDIA Jetson Nano) introduces a feasible pathway for real-time or near-real-time enhancements in the clinic. This scalability is also valuable for telemedicine applications. In remote teleconsultations, higher-quality images reduce diagnostic ambiguities when experts are offsite, thus accelerating second opinions and facilitating timely interventions. Such setups can play a pivotal role in underserved regions, where specialist access is limited and internet bandwidth is often constrained.

Cost effectiveness and equipment lifespan. Financial constraints frequently limit the procurement of advanced imaging systems. SR can extend the usable lifespan of older ultrasound machines, allowing facilities to maintain diagnostic capabilities comparable to modern systems without incurring excessive replacement costs. Hospitals and small clinics could reallocate budgets more effectively, potentially increasing the number of ultrasound devices in operation rather than purchasing a few high-end machines.

Outlook and future directions. Although SR shows promise, future research needs to broaden the scope of training data to encompass a wider range of fetal conditions and patient demographics. Evaluations could be expanded to time-series ultrasound (video) for improved fetal movement tracking. Additionally, collaborations with manufacturers might yield ultrasound machines pre-equipped with SR options, further optimizing diagnostic pathways. With advances in federated learning, privacy-preserving systems could be established, thus boosting data sharing for model improvement while respecting patient confidentiality.

Overall, by improving image clarity where it is needed most and minimizing the technological and training gaps in developing countries, SR strategies hold promise as a cost-conscious and practical approach to elevating prenatal care globally.

Conclusion

In this paper, our findings indicate that the analysis of super-resolution (SR) model performance in Africa, based on PSNR, SSIM, BRISQUE, and NIQE metrics, and classification performance (Accuracy, F1 Score, Kappa), reveals interesting but nuanced results. Real-ESRGAN emerged as a promising candidate, consistently demonstrating strong performance, characterized by high image quality metrics and robust classification accuracy. This is particularly noteworthy given the inherent limitations of smaller, less diverse datasets and the variability in image quality often encountered in African healthcare settings.

However, we observed some performance fluctuations with Real-ESRGAN across different datasets, suggesting a potential sensitivity to training data characteristics such as dataset size and image diversity. This highlights the importance of carefully considering data constraints when selecting and deploying such models.