Abstract

The Chi and Mun River Basins, the primary tributary of the Mekong River Basin in Thailand, is undergoing significant land use changes that impact water quality. Understanding the relationship between land use and water quality is crucial for effective river basin management, providing insights applicable to global water systems. While past studies have examined water quality in the Mekong River Basin, research specifically focusing on the Chi-Mun River Basin remains limited. This study analyzes the spatial and temporal effects of land use changes on water quality from 2007 to 2021 using land use change estimation, 11 water quality parameters, and redundancy analysis (RDA). Water samples were collected in January, March, May, and August across multiple years. Seasonal variations were assessed, with dry season samples from January and March and wet season samples from May and August. Key findings include: (1) pH, Biochemical Oxygen Demand, Total Coliform Bacteria, Fecal Coliform Bacteria, Total Phosphorus, Nitrate Nitrogen, Ammonia-Nitrogen, and Suspended Solids increased during the wet season, while (2) Dissolved Oxygen, Electrical Conductivity, and Water Quality Index were higher in the dry season. (3) Land use changes had a greater impact on water quality during the wet season, driven by increased runoff from expanding urban and agricultural areas and declining paddy and forest cover. (4) Forests and aquatic areas improved water quality, while agricultural and urban expansion contributed to its deterioration. These findings underscore the need for sustainable land management strategies to balance regional development with ecological conservation in the Chi-Mun River Basin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Both natural and human-induced factors contribute to changes in water quality, with human activities playing a dominant role in water quality degradation due to land use changes, urbanization, and agricultural runoff1,2. Intensive human activities can affect land use patterns, thereby influencing water quality1,2. The quality of water plays an essential role in protecting habitats, supporting agriculture, sustaining industry, and safeguarding public health3,4. Maintaining water quality is difficult due to both point-source (PS) and nonpoint-source (NPS) pollution. PS pollution primarily includes industrial and domestic wastewater loads, which can be relatively easily identified5. In contrast, NPS typically comes from diffuse sources like agriculture, runoff, and the deposition of atmospheric pollutants6. Identifying NPS pollution is complicated by the complex interplay of rainfall and landscape characteristics4. As the social economy, industry, agriculture, and urbanization continue to progress, water quality will inevitably decline7.

The response of the surface water environment to changes in land use patterns has been extensively studied for decades8, with increasing emphasis on spatial and temporal variability in more recent years9,10. Land use changes have indirect effects on water quality by changing land surface characteristics, affecting regional hydrological cycles, and biochemical cycles11. This study examines these relationships at the large river basin scale, focusing on the Chi-Mun River Basin, which covers approximately 120,000 km2, making it one of the largest tributaries of the Mekong River Basin. For example, changes in land use led to variations in land cover types and the intensity of land use12, which affect the soil’s capacity to retain water and soil erosion13. These changes impact processes such as evapotranspiration14, runoff formation15, and groundwater recharge16, leading to the accumulation of pollutants17,18. Urbanization, for instance, increases surface runoff, reduces evaporation and infiltration, and increases the accumulation of pollutants19. Therefore, the impact of different land use types on water quality varies significantly across spatial and temporal scales11.

Temporal and spatial variations in land use patterns, along with differences in scale, create uncertainty in understanding how different land use types impact water quality20. As a result, researchers mainly investigate understanding how water quality responds at different scales, with most existing studies concentrating on sub-basin and river scales21,22. Several studies have shown that land use within river buffers has a greater impact on water quality than at the sub-basin level. However, the exact scale at which riparian buffers most significantly influence water quality remains unclear due to variations in location and research methodology23,24,25. Therefore, this study examines various spatial scales of sub-basin for analysis. The high-intensity rainfall during the wet season can have a considerable impact on water quality in the watershed. This has led to increased research focus on the relationship between seasonal changes in land use and water quality in the river basin26,27. Due to the complex nature and the effects of land use changes, the response of water quality to seasonal variations remains an important area of research.

According to Santana and Blanco28, river basins can be classified into small (< 2,000 km2), medium (2,000–50,000 km2), and large (> 50,000 km2) categories based on drainage area, geomorphology, and hydrology. This classification framework helps contextualize how land use influences water quality at different spatial scales. For instance, research conducted in 1995 on the Bentong River in Malaysia revealed that forests possess strong water purification capabilities29. Wei et al.30 investigated the water quality of different lakes and reservoirs in China by considering land use types, while Zhou et al.31 inspected the correlation between land use and water quality in the Shiyang River Basin on the northern slope of the Qilian Mountains. However, there is research focusing on large-scale basins and comparative studies between basins32,33,34. Large-scale basins encompass extensive areas, including multiple regions and cities, as well as diverse landforms and ecosystems. It is crucial to understand the impact of land use patterns on water quality in large-scale basins for water resources management, ecological conservation, and regional development planning. Moreover, given the ongoing societal progress, regional coordinated development is increasingly critical, surpassing the adequacy of single-basin studies. Comparative studies between basins can not only uncover shared geographical processes and rules but also deliver water quality response outcomes tailored to the distinctive characteristics of each basin by integrating their unique natural and social environments35. These studies can advance water environmental protection and sustainable development in diverse basins, and offer guidance in formulating cross-regional water quality and land management policies36,37. Extensive research has investigated the relationship between land use and water quality, showing that seasonal and spatial variations significantly influence water quality trends across river basins38,39. For example, previous studies in China (Wei River Basin, Huai River Basin), as well as in Southeastern Brazil40, South Korea41, and Thailand42, demonstrate how different land use patterns impact water quality at various scales. This study focuses on the Chi-Mun River Basin in Thailand, where distinct monsoon-driven variations influence land use and water quality interactions.

Studies on the correlation between land use patterns and changes in water quality within river basins highlight the complex interactions among human activities, spatial dimensions, and hydrological processes. Yu et al.38 determined that land use types substantially affect stream water quality, with seasonal changes and topographic features serving as moderating factors in the Wei River Basin, China. Yao et al.39 examined the influence of land use patterns on seasonal water quality in Chinese basins across temporal and spatial dimensions, revealing a complex interaction of local and watershed-level influences. Liu et al.43 highlighted that the impact of land use on water quality in the Huai River Basin is dependent upon geographical scale and seasonal variations, highlighting the dynamic characteristics of these interactions.

Seasonal variations in water quality are influenced by both land use gradients and hydrological processes. Urbanization often exacerbates pollution levels due to increased runoff and wastewater discharge44. In the Dan River Basin, seasonal shifts in water quality were closely linked to precipitation patterns and agricultural activity, highlighting the role of climate-driven hydrological changes45. River buffer zones play a crucial role in mitigating land use impacts on water quality, with targeted management strategies improving nutrient retention in low-order streams40. Additionally, in tropical basins such as the Johor River Basin, point source pollution and land use configuration significantly influence seasonal water quality variations46. These studies collectively underscore the scale-dependent nature of land use impacts, emphasizing the need for integrated management approaches that account for spatial and seasonal variability in hydrological systems47.

This study examined the Chi-Mun River Basin in Thailand (refer to Fig. 1) and analyzed the relationship between land use changes and water quality at a large river basin scale, representing the inaugural investigation of this correlation within the Chi-Mun Basin of the Mekong River Basin. This study is novel due to its multi-scale approach in analyzing the effects of land use changes on water quality, offering insights at both localized and basin-wide levels. This research addresses a significant knowledge gap in Thailand and the Mekong region, contributes to integrated development across various regions, and provides valuable insights for comparative studies on large-scale river basins worldwide. The findings aim to improve cross-regional water quality and land management policies, promoting sustainable development and environmental conservation strategies. This study has three objectives: (1) to characterize the spatial and temporal variations in land use change patterns and water quality parameters within the Chi-Mun River Basin; (2) to quantify the correlation between land use change patterns and water quality in the basin; and (3) to investigate the multi-scale impacts of land use change patterns on water quality parameters.

Study area, (a) the location of the study area in Thailand, (b) the topography of the study area as the Chi-Mun River basin, and (c) the location of the observation points in the red box of the figure b. The blue line is the river network and the triangle is the observation points, red in Chi River and blue in Mun River. The figure was created by using a QGIS software version 3.34.7-Prizren (http://www.qgis.org). The basemap was collected from QuickMapServices (https://github.com/nextgis/quickmapservices). The topography in the (b) was the data from Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (https://dwtkns.com/srtm30m/).

Materials and methods

The methodology, illustrated in Fig. 2, integrates three key components: (1) estimation of land use changes, (2) seasonal analysis of the water quality parameters, and (3) assessment of the relationship between land use changes and the water quality parameters. These elements align with the study’s objectives, as outlined in the Introduction.

Study area

The Chi-Mun River Basin, located in northeastern Thailand (14°–16° N, 101°–106° E), encompasses the Chi and Mun Rivers, both of which are major tributaries of the Mekong River. Covering 120,000 km2, it provides a crucial role in regional hydrology, with an average annual runoff of 800 m³/s and a total flow contribution of approximately 25,000 million cubic meters (MCM) per year (Fig. 1). This study focuses on analyzing land use changes and their impact on water quality across different hydrological zones within the basin. The majority of this runoff takes place during the rainy season, which spans from April to October, while the dry season is characterized by lower flow rates.

The Basin covers a wide area and has diverse natural and socio-economic conditions, leading to varied land use patterns42,48. Moreover, as a result of the area’s distinct monsoon and continental climate, including the impact of typhoons, significant seasonal and spatial differences in rainfall are evident in major river basins in Thailand. The Chi-Mun River Basin in northeastern Thailand is heavily influenced by the subtropical monsoon climate, receiving annual precipitation ranging from 900 to 1,500 mm, which is comparable to other major basins in the region, such as the Lower Mekong Basin, but generally lower than the Upper Mekong Basin, which experiences higher rainfall due to orographic effects49,50,51,52,53 . These climatic patterns make the region particularly vulnerable to the effects of global climate change, including shifts in precipitation intensity and distribution, which can exacerbate droughts, floods, groundwater depletion54, and water pollution55. Additionally, rising temperatures and altered rainfall patterns could significantly impact water availability56, agricultural productivity57, and ecosystem stability in the basin.

The rainfall in the river basin is predominantly influenced by the monsoon during the rainy season, with an annual precipitation range of approximately 900 to 1,500 millimeters. The topography of the river basin features mountains along the border and flat terrain in the central area, with elevations ranging from 200 to 2,000 m. The natural vegetation in the basin primarily consists of forests and shrubs.

Thailand’s climate is characterized by a dry season (November–March) and a wet season (May–October), primarily influenced by monsoonal rainfall patterns58,59. These seasonal variations significantly impact hydrological and water quality dynamics in the Chi-Mun River Basin.

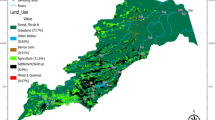

Land use data

The land use change pattern in the Chi-Mun River Basin was estimated using data from the Land Development Department (http://www1.ldd.go.th/), Thailand. The dataset, collected from 2007 to 2021, classifies land use into eight categories: paddy fields, agriculture, farms, aquacultural agriculture, forest, miscellaneous, urban areas, and water (as shown in Fig. 3). While ‘agriculture’ broadly includes paddy fields and farm areas, we retained this detailed classification to reflect the dataset’s structure and provide a more precise analysis of land use impacts on water quality. We used the Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS 3.34.7-Prizren, http://www.qgis.org) to evaluate the importance of the spatial extent of the effects of land use on water quality in the river basin. Paddy fields are the predominant land use type in the Chi-Mun River Basin, followed by general agricultural land and forested areas. The region practices a combination of single and double cropping, primarily cultivating rice in paddy fields and secondary crops such as maize, cassava, and sugarcane in agricultural zones. Common agricultural practices include fertilizer application, pesticide use, and irrigation during the dry season to support crop growth. These factors influence nutrient runoff and water quality dynamics throughout the year.

Land use data from 2007 to 2021 specific for the red box in Fig. 3e, (a) 2007, (b) 2011, (c) 2017, and (d) 2021. (e) The location of the red box in the Chi-Mun river basin. The figure was created by using a QGIS software version 3.34.7-Prizren (http://www.qgis.org). The basemap was collected from QuickMapServices (https://github.com/nextgis/quickmapservices).

Water quality data

Water quality data was monitored and provided by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (https://rwater.mnre.go.th/) and the eleven sampling stations in the Chi-Mun River are shown in Fig. 1c. Thailand experiences two seasons: the dry season from November to March and the wet season from May to October58,59. Seasonal variations significantly impact hydrological and water quality dynamics in the Chi-Mun River Basin. The time series data of the water quality, as shown in Fig. 4, were split into two seasons, wet and dry. Seasonal water quality variations were assessed by collecting samples in January and March, representing the dry season (November–March), and in May and August, representing the wet season (May–October). The selected months were chosen to properly represent changes in water quality. To analyze the environmental quality of the surface water presented by eleven parameters: pH, Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), Total Coliform Bacteria (TCB), Fecal Coliform Bacteria (FCB), Total Phosphorus (TP), Nitrate Nitrogen (NO3-N), Ammonia-nitrogen (NH3-N), Suspended Solids (SS), Electrical Conductivity (EC), and Water Quality Index (WQI). The WQI from 5 parameters (DO, BOD, TCB, FCB, and NH3-N) can be estimated by \(WQI=\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{N}{WQI}_{i}}{N}\) where the \({WQI}_{i}\) for each parameter can be estimated by using the Figure S1.

Statistical analysis

The water quality data’s normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The independent samples t-test was employed to verify seasonal variations in water quality parameter concentrations to compare two independent samples for significant differences. Spatial distinctions among water quality parameters across monitoring stations were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant differences among multiple independent samples. Redundancy Analysis (RDA) is a multivariate statistical technique that integrates multiple linear regression with Principal Component Analysis (PCA). It identifies how much variation in a set of response variables (e.g., water quality parameters) can be explained by a set of explanatory variables (e.g., land use types). In this study, RDA was used to evaluate the relationship between land use and water quality patterns across different seasons60. We utilized the R (https://www.R-project.org/)61 platform’s RDA library62 to investigate changes in water quality and land use types across various spatial scales within the river basin. In the RDA analysis plot, two distinct types of arrows symbolize response variables and explanatory variables, respectively. If the angle between the arrows of two variables is acute, they are positively correlated; if the angle is obtuse, they are negatively correlated. Moreover, the angle between the arrows changes inversely with the degree of correlation between the two variables. The impact of each variable on water quality is directly proportional to the length of the arrows. Furthermore, RDA analysis evaluates how much each type of land use explains changes in all water quality parameters63. The percentage of variation explained by land use predictors was obtained from the RDA eigenvalues, where the first two axes accounted for 90% of the total variance in water quality parameters. The RDA results illustrate the relative contributions of different land use types across seasons.

Results

Land use change

The land use in the Chi-Mun River Basin was analyzed from 2007 to 2021. The percentage of each land use type and the changes over time are shown in Fig. 5. From 2007 to 2021, the paddy field area declined from 50 to 43%, with the most significant reduction occurring between 2009 and 2010 (Fig. 5a). Meanwhile, agriculture expanded from 20 to 27.5%, with a peak increase in 2016 (Fig. 5b). Urban areas grew steadily from 5.25 to 6.5%, particularly between 2013 and 2014 (Fig. 5g). Forest cover declined from 16.5 to 14.5%, with the sharpest drop between 2016 and 2017 (Fig. 5e). Additionally, aqua agriculture, water bodies, and miscellaneous land use showed minor fluctuations, while farm areas exhibited a temporary increase before stabilizing at 0.3% in 2021 (Fig. 5c). These trends highlight ongoing land conversion, particularly the expansion of agriculture and urban areas at the expense of forests and paddy fields.

Land use changes in the Chi-Mun River Basin from 2007 to 2021. The first column presents the total percentage of land use types for each year, while the second column highlights year-over-year changes in land use. Blue areas indicate an increase, while orange areas indicate a decrease compared to the previous year. (a) Paddy, (b) Agriculture, (c) Farm, (d) Aqua agriculture, (e) Forest, (f) Miscellaneous, (g) Urban, and (h) Water.

Temporal variation of water quality

The analysis of Fig. 4 reveals that water quality parameters in the Chi-Mun River Basin exhibited notable variations over time. The pH average presented approximately 7.3 considering all stations; the pH peak was in 2009. The DO had an average of approximately 3.3 mg/L, the peak of DO was in the wet season of 2007. The BOD was averaged by approximately 1.3 mg/L with a peak in 2015 and 2019. The TCB was 7000 MPN/100 ml as the average value with peaks in 2009, 2010, 2015, and 2017. The FCB had an average value of approximately 0.07 mg/L with a peak at the MU04 station in 2017. The TP was approximately 0.8 of the average value and the peak was approximately 0.1 mg/L at the MU08 station. The NO3-N was represented with 0.7 for the average value with the peak in 2013 and 2015 at the CI01, CI02, and CI03 stations. The NH3-N was average at 0.35 mg/L with two peaks in 2013 and 2017. The SS presented an average value of 21 mg/L with a peak in 2007 and 2014. The EC was 230 µS/cm with a peak in 2021. The WQI was represented by 70 for the average value for all stations.

The results of the independent samples t-test revealed that the levels of pH, BOD, SS, and WQI exhibited statistically significant differences between seasons, with a significance level of P < 0.05, as demonstrated in Fig. 6.

Figure 7 presents the variation in water chemistry parameters, including pH, DO, BOD, TCB, FCB, TP, NO3-N, NH3-N, SS, EC, and WQI, averaged across all monitoring stations during the seasonal time series. The figure shows significant seasonal variations, highlighting how seasonal changes, such as rainfall and runoff, influence water quality dynamics.

Water quality parameters in the Chi-Mun River Basin exhibited distinct seasonal trends from 2007 to 2021 (Fig. 7). pH levels remained stable, fluctuating between 7.2 and 8.0 (Fig. 7a), with minimal long-term change. Dissolved Oxygen (DO) showed an increasing trend, particularly in the dry season, rising from 6 mg/L to 8 mg/L (Fig. 7b), indicating improved oxygenation. In contrast, Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) and nutrient levels (Total Phosphorus, Nitrate Nitrogen, and Ammonia Nitrogen) showed greater variability in the wet season (Fig. 7c, f and g, and h), primarily due to increased runoff from agricultural areas.

Coliform bacteria (TCB and FCB) exhibited significant seasonal variations, with peaks during high rainfall periods, increasing by up to 200–300% compared to the dry season (Fig. 7d and e). Suspended Solids (SS) and Electrical Conductivity (EC) followed expected hydrological patterns, with higher SS concentrations in the wet season due to sediment transport (Fig. 7i) and higher EC values in the dry season due to reduced dilution (Fig. 7j). The Water Quality Index (WQI) remained higher during the dry season, ranging from 70 to 90, but declined during the wet season due to pollutant loading (Fig. 7k).

These findings indicate that seasonal hydrological changes, particularly during the wet season, significantly influence water quality trends, primarily through agricultural runoff and sediment transport. Full parameter details and percentage changes are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Changes in land use, as shown in Fig. 5, are correlated with variations in water quality parameters (Fig. 7), with notable seasonal and annual fluctuations. The pH levels in urban and agricultural areas experienced a decrease of 10–15% during the dry season, whereas forested regions contributed to the stabilization of pH levels during the wet season. Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels experienced a reduction of 20–30%, especially during the wet season, attributed to heightened organic matter and nutrient runoff originating from urban and agricultural areas. The increase in biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) by 25–35% indicates a significant increase in organic pollution inputs. During the wet season, there was a notable increase of 30–50% in total coliform bacteria (TCB) and fecal coliform bacteria (FCB) levels, primarily caused by runoff, especially from paddy fields. During the wet season, Total Phosphorus levels (TP) experienced an increase of 50–100% as a result of runoff from urban and agricultural areas. Concurrently, nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) and ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) observed an increase of 100–300%, primarily caused by application of nutrients. During the wet season, levels of suspended solids (SS) increased significantly, ranging from 100 to 400%, indicating the movement of sediment from urban and agricultural areas. The dry season exhibited increased electrical conductivity (EC), with an effect size ranging from 10 to 30%, which was caused by the concentration of ions under low-flow conditions. The overall Water Quality Index (WQI) declined by 20–30% during the wet season, primarily due to increased runoff carrying pollutants from agricultural and urban areas. In contrast, forested regions and water bodies played a protective role by reducing nutrient and sediment levels, demonstrating their function as natural water filters (Fig. 9). The results highlight the significant seasonal influence of land use changes on water quality, with the wet season showing the strongest effects due to increased runoff carrying pollutants from agricultural and urban areas.

Effect of land use on water quality

The redundancy analysis (RDA) method measured the influence of different land uses on water quality throughout different seasons. It identified Farm, Forest, and Urban as the land use types with the most significant impact on water quality during the dry season (Fig. 8a). During the wet season, Paddy had the highest effect on water quality, followed by Farm and Urban (Fig. 8b). For the annual period, Paddy, Farm, Forest, and Urban contributed the most to water quality changes (Fig. 8c). The RDA results showed that the impact of land use types on water quality varied significantly depending on the season. Specifically, the response of water quality to land use was more pronounced during the dry season. Overall, land use predictors explained approximately 90% of the total variance in water quality, as determined through RDA eigenvalues (Fig. 9).

The specific land use types that had the most significant impact on water quality were identified based on their contribution rates. During the dry season, the Farm land use type had a substantial influence, accounting for 20.5% of the impact on water quality. However, higher contaminant concentrations in the dry season may be partially attributed to lower river flow, which reduces dilution capacity. In contrast, pollutant loads (total mass transported) are generally higher in the wet season due to increased runoff. This suggests that while concentrations are elevated in the dry season, the total pollutant transport is likely greater during heavy rainfall events. Together, these two land use types represented 21.9% of the annual impact on water quality. This is attributed to the increased precipitation during the wet season, which washes pollutants from the Paddy areas into nearby water bodies, leading to changes in water quality. These findings are visually represented in Figs. 8 and 9, illustrating the varying impact of different land use types on water quality across different seasons.

The RDA (Redundancy Analysis) plot provides a visual representation of the relationships between different land use types and water quality parameters. In Fig. 9, the angles between arrows representing different variables reflect the varying correlations between land use types and water quality parameters.

Figure 9a presents a relationship between different types of land use (indicated by blue arrows) and water quality parameters (represented by red arrows) during the dry season, employing redundancy analysis (RDA). The arrows’ length and angle indicate the strength and direction of correlations, with values that are derived from the figure. The relationship between urban and electrical conductivity (EC) is specifically strong, with an RDA value of approximately 0.8. Similarly, biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) presents a significant correlation, reflected in an RDA value approximately 0.6. This correlation is primarily affected by the release of salts and organic pollutants caused by untreated domestic wastewater and industrial operations, which tend to be more concentrated in the dry season due to reduced dilution effects. The productive use of agricultural area shows a positive correlation with nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) (RDA value approximately 0.7) and ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) (RDA value approximately 0.5). This relationship is attributed to runoff, which increases nitrogen concentrations in stream water, especially during irrigation periods. Paddy fields function as nutrient sinks, presenting a negative correlation with electrical conductivity (EC) (RDA value approximately − 0.3) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) (RDA value approximately − 0.2). It effectively captures organic and inorganic pollutants during the dry season, therefore improving water quality. The productive use of farmland shows a significant relationship with fecal coliform bacteria (FCB), indicated by an RDA value of approximately 0.4. This correlation is caused by the impact of livestock waste and manure drainage, which contributes to heightened bacterial contamination, particularly in stagnant waters. Water bodies demonstrate negative correlations with NO3-N (RDA value approximately − 0.6) and NH3-N (RDA value approximately − 0.5), indicating their ability to dilute nutrient concentrations and mitigate nitrogen-based pollutants.

Based on redundancy analysis (RDA), Fig. 9b shows the connections between water quality measures (red arrows) and changes in land use (blue arrows) during the wet season. The RDA analysis indicates the relationship between land use practices and water quality parameters, highlighting the impact of runoff and heightened precipitation during the wet season. The relationship between urban and electrical conductivity (EC) is especially positive, with an RDA value of approximately 0.7. Additionally, total phosphorus (TP) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) reveal similar positive correlations, each with RDA values approximately 0.6. This is caused by stormwater runoff from urban areas, which transports salts, organic material, and phosphorus from wastewater and impervious surfaces into waterways. Agricultural shows a significant positive correlation with nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) (RDA value approximately 0.8) and ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) (RDA value approximately 0.7). This relationship is mainly caused by runoff during the wet season, leading to increased nitrogen levels in rivers. Paddy fields reveal a negative correlation with fecal coliform bacteria (FCB) (RDA value approximately − 0.4) and suspended solids (SS) (RDA value approximately − 0.5) in order to retain runoff and filter pollutants during periods of heavy precipitation. Forested regions indicate a negative correlation with total phosphorus (TP), as indicated by an RDA value of approximately − 0.3, functioning as natural buffers that mitigate phosphorus runoff. Water bodies reveal negative correlations with NH3-N and NO3-N, with RDA values approximately − 0.5 for each, indicating their contribution in diluting nutrient concentrations and improving water quality.

Using redundancy analysis (RDA), Fig. 9c shows the yearly correlations between data on water quality (red arrows) and changes in land use (blue arrows). The relationships indicate the relationship between seasonal variations and land use practices over a period of the year. Urban demonstrate a significant positive correlation with electrical conductivity (EC) (RDA value approximately 0.8) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and total phosphorus (TP) (RDA values approximately 0.7). This relationship occurs as urbanization contributes salts, organic matter, and phosphorus to water bodies via wastewater discharge and stormwater runoff consistently throughout the year. Agricultural shows strong positive correlations with nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) (RDA value approximately 0.8) and ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N) (RDA value approximately 0.7), caused by runoff that increases nitrogen concentrations in streams, especially during rainy periods. Paddy fields reveal a negative correlation with fecal coliform bacteria (FCB) (RDA value approximately − 0.3) and suspended solids (SS) (RDA value approximately − 0.4), performing as natural filters that diminish bacterial contamination and sediment transport. Forests indicate a negative correlation with total phosphorus (TP) (RDA value approximately − 0.4), and thus mitigate nutrient runoff and improve water quality through soil stabilization and the reduction of surface flows. Water bodies exhibit a dilution effect on nitrogen-based pollutants, demonstrating negative correlations with NO3-N and NH3-N (RDA values approximately − 0.6 for both), which results in reduced concentrations and a subsequent alleviation of their effects on water quality.

Discussion

This discussion examines the relationship between land use patterns and water quality, acknowledging that while land use data were analyzed over time, a direct temporal assessment of land use change was not conducted. It looks at how factors such as agriculture, urbanization, and forestry can affect water ecosystems by introducing nutrients. Understanding these relationships is crucial for effective water resource management. The discussion also considers the impact of seasonal variations and long-term trends on water quality, providing important insights into the dynamics of river basins. Additionally, practical suggestions for river basin management emphasize the need for integrated strategies that consider both land use practices and temporal variability to protect water quality and maintain ecological balance.

As a large-scale river, the Chi-Mun River Basin presents certain features the particular set it from the smaller-scale basins that have been the subject of previous research. While the Chi-Mun River Basin includes diverse land use types and climatic conditions, this study focused on seasonal variations in water quality rather than geographical differences between sub-regions. A spatial analysis at the sub-basin level could provide further insights into geographical influences on water quality. Previous studies have shown that nutrient concentrations and suspended solids tend to increase during the wet season due to higher runoff, while dissolved oxygen and electrical conductivity are more prominent in the dry season64,65. The basin’s extensive hydrological and land-use variation increases this variation. In contrast to smaller basins, the Chi-Mun River’s the extent results in reduced pollution dispersion during the dry season, especially in its large plains, and increased pollutant deposition driven by runoff in its upstream highlands during the wet season. These findings highlight the necessity of accounting for the different dynamics of large-scale basins when evaluating the effects of land use on water quality. This research underlines the significance of specific management strategies for large basins, tackling their fundamental difficulties and providing sustainable enhancements in water quality.

Relationships between land use change and water quality

This study examined the influence of various land use patterns on water quality across different spatial and temporal scales, as shown in Fig. 9. Agriculture, Aqua agriculture, Urban, and Water were found to positively affect water quality, while Paddy, Farm, Forest, and Miscellaneous had a negative impact, consistent with previous research findings64,66,67. The Redundancy Analysis (RDA) in Fig. 9 showed distinct relationships between land use types and water quality parameters during dry, wet, and annual periods. The observed correlations between land use changes and water quality parameters suggest that urbanization and agriculture contribute to increased pollutant loads, particularly during the wet season. Runoff from agricultural areas likely elevates nitrogen and phosphorus levels, while urban expansion increases biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and electrical conductivity (EC) through wastewater and stormwater discharges. Additionally, forests and paddy fields act as natural buffers, mitigating the effects of nutrient and sediment transport (Fig. 9). While this study does not directly assess the mechanisms behind these changes, the findings align with existing literature on land use impacts on water quality.

Urban and Agriculture (cropland) areas exhibited strong positive correlations with EC, WQI, and other pollutants, particularly in regions dominated by agriculture and urbanization in the Chi-Mun basin. The area was characterized by intensive farming and urban expansion, contributing significantly to nonpoint source pollution due to runoff containing excess fertilizers, pesticides, and organic waste from livestock. The urban area also introduced pollutants, including heavy metals and organic matter from industrial and domestic sources, into nearby water bodies65,68.

Conversely, Forest, Miscellaneous, and Water, as a natural area, were associated with improved water quality. These ecosystems negatively correlated with BOD, DO, WQI, and NH3-N, indicating their role in filtering pollutants and reducing nutrient loads33. If the concentration of inorganic nitrogen surpasses 0.3 mg/L in the spring, it indicates an adequate nitrogen level to facilitate the growth of summer algae blooms69. Vegetation can mitigate soil erosion, intercept chemical runoff, and absorb nutrients, while Water enhanced water quality through hydrological regulation and nutrient transformation70,71. Moreover, the natural filtration processes of aquifers and riverbeds help purify water, particularly during low precipitation periods, ensuring a balance in water quality and ecosystem health72.

Effect of temporal scale on water quality

The RDA results showed that there are variations in the correlation between land use patterns and water quality indicators across the Chi-Mun basins. In the dry season, land use has a more significant impact on water quality compared to the wet season. This is because the undulating terrain in the basins affects the flow rate of surface runoff, which in turn influences the rate of pollutant accumulation, absorption, and transformation, leading to different water quality results in the basins73.

Industrial and wastewater discharges increase electrical conductivity (EC) and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) in dry season by urban. Agriculture, especially use, raises nitrate and ammonia levels. In the dry season, contaminants are less diffused, increasing concentrations. The modest positive correlation between farms and fecal coliform bacteria (FCB) indicates livestock and runoff, a significant dry-season contaminant. Forests and paddy fields filter and buffer pollutants including EC and BOD, as shown by its adverse associations. Smaller water bodies decrease nutrient concentrations, reducing nitrogen-based pollution.

Urbanization contributes high levels of EC, TP, and BOD (RDA values approximately 0.6–0.7) to water bodies during the wet season due to stormwater runoff carrying salts, organic contaminants, and nutrients. Activities in agriculture increase NO3-N and NH3-N concentrations (RDA values approximately 0.7–0.8) due to chemical poured into streams after rainfall. Trapping sediments and runoff, paddy fields buffer suspended particles (RDA value approximately − 0.5) and fecal coliform bacteria (RDA value approximately − 0.4). Forests reduce phosphorus burdens (RDA approximately − 0.3) by absorbing nutrients and reducing surface runoff. Larger water bodies disperse nitrogen compounds, reducing NH3-N and NO3-N concentrations (RDA values approximately − 0.5 each) and improving water quality during heavy rains.

Urbanization significantly impacts water quality by increasing EC, BOD, and TP levels (RDA values approximately 0.7–0.8) annually due to contaminants such salts, organic matter, and phosphorus entering streams from industrial discharge, untreated wastewater, and stormwater runoff. Agricultural activities, especially the use of fertilizers, greatly increase NO3-N and NH3-N levels (RDA values approximately 0.7–0.8). Farming and irrigation contribute to nitrogen and phosphorus contamination throughout the year. During the wet season, rainfall-induced runoff mobilizes fertilizers from fields, increasing nitrate (NO₃-N) and ammonia (NH₃-N) levels in surface water. In the dry season, irrigation practices lead to localized nutrient leaching and higher contaminant concentrations due to reduced river dilution capacity. Paddy fields buffer runoff, reducing sediment loads (SS, RDA value ≈ -0.4) and contaminants from feces (FCB, RDA value approximately − 0.3). Forests reduce discharges of phosphorus (TP, RDA value approximately − 0.4) by stabilizing soils and capturing surface flows. Water bodies reduce nitrogen-based contaminants as NO3-N and NH3-N (RDA values approximately − 0.6 each), improving water quality, especially in more expansive water.

For instance, in the middle and lower parts of the Chi-Mun River, where there are numerous plains and a dense river network, slow water flow in river channels during the dry season leads to the accumulation of pollutants, which negatively affects water quality. On the other hand, the highland areas upstream of the basin have loose soil that is easily eroded by rainwater, significantly affecting water quality in the wet season. Additionally, precipitation and river flow strongly influence agricultural runoff. During the wet season, heavy rainfall increases surface runoff, transporting fertilizers and pesticides from farmlands into waterways. In contrast, irrigation practices during the dry season maintain soil moisture for crops but can also contribute to nutrient leaching and increased contaminant concentrations in river systems. Excessive and heavy precipitation can lead to changes in river flow, weakening the regulation of pollutants by wet season land use patterns21,74,75.

Crop growth and cultivation times vary due to differences in temperature and precipitation, and the use of large quantities of fertilizers and pesticides during the cultivation period results in a rapid increase in pollutant concentrations, leading to significant changes in water quality76. Consequently, the contribution of the wet season differs from that of the dry season.

Suggestion for river basin management

The Northern part of Thailand is experiencing ongoing urbanization, posing significant challenges to the ecological water environment in the Chi-Mun basin. It is crucial to develop effective land management policies and implement ecological protection measures to address these challenges. Vegetation and water play a vital role in improving water quality in the basin, highlighting the need to prioritize their protection in policy formulation. Measures such as returning farmland to forests and establishing vegetation protection zones are essential for enhancing ecological construction within the basin. Agriculture and urban activities have a negative impact on water quality in all basins, but this can be mitigated through careful planning, precise fertilizer application, and proper wastewater treatment before discharge.

In addition to common characteristics, geographic and socio-economic factors also influence the environment in the basin. During the wet season, soil erosion, surface undulation, and certain land use types have negative impacts on water quality, necessitating better prevention of winds and sand, and reduction of agriculture and urban land use. To mitigate wet season runoff impacts, strategies such as buffer zones, river vegetation restoration, and controlled drainage systems can be implemented. These measures help reduce sediment transport, filter excess nutrients before reaching water bodies, and stabilize soil in high-runoff areas. During the dry season, safeguarding water quality is critical, requiring repairs and improvements to the substrate, enhancing the river’s self-purification capacity, and reducing agricultural runoff through measures such as water transfer projects and construction of artificial wetlands, as well as adopting efficient water-saving irrigation techniques.

Limitation and future works

The present study offers significant insights into the relationship between land use change and water quality in the Chi-Mun River Basin; at this point numerous limitations should be considered. The temporal resolution of water quality data collection, limited to four sample events annually, is unable to detect short-term variations in water quality resulting from intense weather events or abrupt changes in land use. Secondly, although the study investigates the relationships between land use and water quality, it does not quantify the direct causal pathways, highlighting the need for advanced modeling techniques or experimental research. The research is confined to publicly accessible datasets, which may possess fundamental concerns about correctness and completeness.

Future studies should concentrate on limiting these constraints by integrating higher-frequency water quality assessments to detect temporary variations and extreme occurrences. Moreover, the integration of hydrological and transport of contaminants models could encourage the establishment of causal relationships between changes in land use and specific water quality parameters. Increasing the scope to include social and economic elements affecting land use patterns could augment the relevance of findings for policies. Ultimately, applying remote sensing and machine learning techniques may enhance the spatial and temporal resolution of land use and water quality information, providing a more thorough comprehension of basin-wide dynamics.

Conclusion

Urban and agricultural areas have a major effect on water quality during the dry season, raising EC, BOD, NO3-N, and NH3-N (RDA values 0.5 to 0.8). However, paddy fields, woodlands, and water bodies buffer pollutants and lower concentrations, improving water quality with RDA values between − 0.2 and − 0.6. Sustainable land management measures including wastewater treatment and constrained fertilizer use can reduce pollution loads during low-flow seasons.

Runoff from urban and agricultural land usage during the wet season significantly increases pollutants including EC, WQI, NO3-N, and NH3-N (RDA values = 0.6–0.8). Paddy fields, forests, and water bodies have lower chemical loads, with negative correlations for FCB, SS, and nitrogen compounds (RDA values − 0.3 to -0.5). Improved runoff management, especially in urban and agricultural areas, is needed to reduce wet season water quality consequences.

Annually, urban and agricultural areas significantly increase contamination loads, exhibiting positive correlations (RDA values ≈ 0.7–0.8) for EC, BOD, TP, NO3-N, and NH3-N. Conversely, paddy fields, forests, and water bodies have lower contamination levels, exhibiting negative correlations with SS, FCB, and nitrogen compounds (RDA values − 0.3 to − 0.6). These findings emphasize the necessity for sustainable urban and agricultural management to protect water quality.

This study revealed several important conclusions concerning the correlation between land use changes and water quality in the Chi-Mun River Basin: (1) Important variation in water quality examines have been observed, with high levels of chemicals including BOD, TCB, FCB, TP, NO3-N, NH3-N, and SS during the wet season, whereas DO, EC, and WQI were greater in the dry season. (2) The influence of land use change on total water quality was more significant during the wet season, with agricultural and urban areas having the most substantial effects. (3) Paddy and forest regions exhibited purifying benefits by reducing pollutant levels, while urban and agricultural land uses correlated with increased concentrations of nutrients, suspended particles, and bacterial contamination. (4) Annually, paddy, agricultural, forest, and urban land uses collectively contributed to approximately 90% of the change in water quality throughout the basin. (5) These findings highlight the necessity for specialized land use and water quality management measures that adapt to the particular features of the Chi-Mun River Basin in order to encourage sustainable development and balance in the environment.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Thailand, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Thailand.

References

Tong, S. et al. A novel framework to improve the consistency of water quality attribution from natural and anthropogenic factors. J. Environ. Manag. 342, 118077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118077 (2023).

Wang, Y. B. et al. Effects of land-use patterns on seasonal water quality at multiple Spatial scales in the Jialing river, Chongqing China. Catena 234, 107646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107646 (2024).

Akasaka, M., Takamura, N., Mitsuhashi, H. & Kadono, Y. Effects of land use on aquatic macrophyte diversity and water quality of ponds. Freshw. Biol. 55(4), 909–922 (2010).

Liu, R., Xu, F., Zhang, P., Yu, W. & Men, C. Identifying non-point source critical source areas based on multi-factors at a basin scale with SWAT. J. Hydrol. 533, 379–388 (2016).

Wang, W., Liu, X., Wang, Y., Guo, X. & Lu, S. Analysis of point source pollution and water environmental quality variation trends in the Nansi lake basin from 2002 to 2012. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 23(5), 4886–4897 (2016).

Ongley, E. D., Xiaolan, Z. & Tao, Y. Current status of agricultural and rural non-point source pollution assessment in China. Environ. Pollut. 158(5), 1159–1168 (2010).

Yang, H., Jia, C., Yang, F., Yang, X. & Wei, R. Water quality assessment of deep learning-improved comprehensive pollution index: A case study of Dagu river, Jiaozhou Bay China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(25), 66853–66866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27174-z (2023a).

Tong, S. T. Y. & Chen, W. Modeling the relationship between land use and surface water quality. J. Environ. Manag. 66, 377–393 (2002).

Peng, F. et al. Urbanization drives riverine bacterial antibiotic resistome more than taxonomic community at watershed scale. Environ. Int. 137, 105524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105524 (2020).

Xue, B., Zhang, H., Wang, G. & Sun, W. Evaluating the risks of spatial and temporal changes in nonpoint source pollution in a Chinese river basin. Sci. Total Environ. 807, 151726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151726 (2022).

Crites, R., Beggs, R. & Leverenz, H. Perspective on land treatment and wastewater reuse for agriculture in the Western United States. Water 13(13), 1822. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13131822 (2021).

Van Kranenburg, G. D., Diekman, W. J., Mulder, S. R. H., Pijnenborg, W. G., Mulder, C. L. & G. H., & Determinants of quality of life and treatment satisfaction during long-term involuntary in-patient treatment of dual-diagnosis patients. Front. Psychiatry 13, 801826. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.801826 (2022).

Mahesh, R. et al. A methodological framework for assessing sea level rise impacts on nitrate loading in coastal agricultural watersheds using SWAT+: A case study of the Tar-Pamlico river basin, North Carolina, USA, science of the total environment, 951, 175523 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.175523

Liu, X. et al. Inconsistent seasonal variation of antibiotics between surface water and groundwater in the Jianghan plain: Risks and linkage to land uses. J. Environ. Sci. 109, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.03.002 (2021).

Tran, T. N. & Lakshmi, V. Enhancing human resilience against climate change: Assessment of hydroclimatic extremes and sea level rise impacts on the Eastern shore of Virginia, United States. Sci. Total Environ. 947, 174289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174289 (2024).

Siddik, M. S., Tulip, S. S., Rahman, A., Islam, M. N., Haghighi, A. T. & Mustafa, S. M. T. The impact of land use and land cover change on groundwater recharge in Northwestern Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115130 (2022).

Zuo, D. et al. The response of non-point source pollution to land use change and risk assessment based on model simulation and grey water footprint theory in an agricultural river basin of Yangtze river, China. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2023.110581 (2023).

Arcega-Cabrera, F. et al. Groundwater quality in the Yucatan Peninsula: Insights from stable isotope and metals analysis. Groundwater 59(6), 878–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.13109 (2021).

Schulte-Uebbing, L. F., Beusen, A. H. W., Bouwman, A. F. & De Vries, W. From planetary to regional boundaries for agricultural nitrogen pollution. Nature 610(7932), 507–512. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05158-2 (2022).

Ding, J. et al. Influences of the land use pattern on water quality in low-order streams of the Dongjiang river basin, China: A multi-scale analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 551–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.162 (2016).

Wang, L. et al. Impacts of land uses on spatiotemporal variations of seasonal water quality in a regulated river basin, Huai river, China. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 159584 (2023).

Zhang, J., Li, S., Dong, R., Jiang, C. & Ni, M. Influences of land use metrics at multispatial scales on seasonal water quality: A case study of river systems in the three Gorges reservoir area, China. J. Clean. Prod. 206, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.179 (2019).

Han, H. et al. Incorporating a new landscape intensity indicator into landscape metrics to better understand controls of water quality and optimal width of riparian buffer zone. J. Hydrol. 625, 130088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130088 (2023).

Mainali, J. & Chang, H. Landscape and anthropogenic factors affecting spatial patterns of water quality trends in a large river basin, South Korea. J. Hydrol. 564, 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.06.074 (2018).

Xu, S., Li, S. L., Zhong, J. & Li, C. Spatial scale effects of the variable relationships between landscape pattern and water quality: example from an agricultural karst river basin, Southwestern China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 300, 106999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106999 (2020).

Shi, P., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Li, P. & Xu, G. Influence of land use and land cover patterns on seasonal water quality at multi-spatial scales. Catena 151, 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2016.12.017 (2017).

Michalak, A. M. Study role of climate change in extreme threats to water quality. Nature 535(7612), 349–350. https://doi.org/10.1038/535349a (2016).

Santana, L. R. & Blanco, C. J. C. Contribution to the classification of small catchments according to the drainage area. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 20(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2020.1776301 (2020).

Shu, X. et al. Impacts of land use and landscape pattern on water quality at multiple spatial scales in a subtropical large river. Ecohydrology 15(3), e2398 (2022).

Wei, W., Gao, Y., Huang, J. & Gao, J. Exploring the effect of basin land degradation on lake and reservoir water quality in China. J. Clean. Prod. 268, 122249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122249 (2020).

Zhou, J. et al. The impact of land use landscape pattern on river hydrochemistry at multi-scale in an inland river basin China. Ecol. Ind. 143, 109334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109334 (2022).

Shi, Z. et al. Molecular characteristics of dissolved organic phosphorus in watershed runoff: Coupled influences of land use and precipitation. J. Environ. Sci. 148, 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2024.01.022 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Scale effects of land use on river water quality: A case study of the Tuojiang river basin China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(16), 48002–48020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-25284-2 (2023b).

Chen, Q. et al. Impacts of land use and population density on seasonal surface water quality using a modified geographically weighted regression. Sci. Total Environ. 572, 450–466 (2016).

Zhou, W., Zhu, Z., Xie, Y. & Cai, Y. Impacts of rainfall spatial and temporal variabilities on runoff quality and quantity at the watershed scale. J. Hydrol. 603, 127057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.127057 (2021).

Ke, Q. & Zhang, K. Scale issues in runoff and sediment delivery (SIRSD): A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Earth Sci. Rev. 251, 104729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2024.104729 (2024).

Ouyang, W. et al. Using river sediments to analyze the driving force difference for non-point source pollution dynamics between two scales of watersheds. Water Res. 139, 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.04.020 (2018).

Yu, S., Xu, Z., Wu, W. & Zuo, D. Effect of land use types on stream water quality under seasonal variation and topographic characteristics in the Wei river basin, China. Ecol. Ind. 60, 202–212 (2016).

Yao, X., Zeng, C., Duan, X. & Wang, Y. Effects of land use patterns on seasonal water quality in Chinese basins at multiple temporal and spatial scales. Ecol. Ind. 166, 112423 (2024).

de Mello, K., Valente, R. A., Randhir, T. O., dos Santos, A. C. A. & Vettorazzi, C. A. Effects of land use and land cover on water quality of low-order streams in southeastern Brazil: Watershed versus riparian zone. Catena 167, 130–138 (2018).

Mainali, J. & Chang, H. Landscape and anthropogenic factors affecting spatial patterns of water quality trends in a large river basin, South Korea. J. Hydrol. (2018).

Champangern, K. et al. Suspended sediment dynamics in the Chi-Mun River basin, Thailand: Impact of climate change and anthropogenic activities. In Proceedings 40th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing, Acrs 2019: Progress of Remote Sensing Technology for Smart Future. October 14–18, 2019, Daejeon Convention Center (DCC), Daejeon, Korea (2020). https://a-a-r-s.org/proceeding/ACRS2019/ThD1-1.pdf

Liu, J. et al. Spatial scale and seasonal dependence of land use impacts on riverine water quality in the Huai River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 20995–21010 (2017).

Vidon, P. et al. Seasonal changes in stream water quality along an agricultural/urban land-use gradient. In Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science Vol. 117, No. 2, 07–123 (2008).

Xu, G. et al. Seasonal changes in water quality and its main influencing factors in the Dan river basin. Catena 173, 131–140 (2019).

Pak, H. Y., Chuah, C. J., Yong, E. L. & Snyder, S. A. Effects of land use configuration, seasonality and point source on water quality in a tropical watershed: A case study of the Johor river basin. Sci. Total Environ. 780, 146661 (2021).

Ye, Y. et al. Seasonal water quality upstream of Dahuofang reservoir, China—The effects of land use type at various Spatial scales. Clean–Soil Air Water 42(10), 1423–1432 (2014).

Adamson, P. T., Rutherfurd, I. D., Peel, M. C. & Conlan, I. A. Chap. 4—The hydrology of the Mekong River. In Aquatic Ecology, The Mekong (eds Campbell, I. C.) 53–76 (Academic Press, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374026-7.00004–8

Kite, G. Modelling the mekong: Hydrological simulation for environmental impact studies. J. Hydrol. 253, 1–13 (2001).

Serbpongpan, M. Study of Characteristics of Sediment in Chi-Mun River Basin, A Thesis of Master degree, Faculty of Engineering Thammasart University (2004).

Artlert, K. & Chaleeraktrakoon, C. Modeling and analysis of rainfall processes in the context of climate change for Mekong, Chi, and mun river basins (Thailand). J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 7, 2–17 (2013).

Li, R., Huang, H., Yu, G., Yu, H., Bridhikitti, A. & Teng, S. Trends of runoff variation and effects of main causal factors in mun river, Thailand during 1980–2018 water 12, no. 3: 831 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/w12030831

Pawar, U., Try, S., Muttil, N., Rathnayake, U. & Suppawimut, W. Frequency and trend analyses of annual peak discharges in the lower Mekong basin. Heliyon 9(9), e19690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19690 (2023).

Tran, T-N-D. et al. Investigating the future flood and drought shifts in the transboundary srepok river basin using CMIP6 projections. IEEE J. Select. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 17, 7516–7529 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2024.3380514

Nguyen, B. Q. et al. Response of streamflow and sediment variability to cascade dam development and climate change in the Sai Gon dong Nai river basin. Clim. Dyn. 62, 7997–8017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-024-07319-7 (2024).

Do, S. K. et al. Assessing terrestrial water storage variations in Afghanistan using GRACE and FLDAS-Central Asia data. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2024.101906 (2024).

Tran, T-N-D., Nguyen, B. Q., Grodzka-Łukaszewska, M., Sinicyn, G. & Lakshmi, V. The role of reservoirs under the impacts of climate change on the Srepok river basin, central highlands of Vietnam. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1304845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2023.1304845 (2023).

Boonriam, W. et al. Effect of fungus-growing termite on CO2 emission from soil at termitaria scales in a seasonal tropical forest. Thail. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 19(6), 503–513. https://doi.org/10.32526/ennrj/19/202100048) (2021).

Chaito, T., Khamkong, M. & Murnta, P. Appropriate transformation techniques to determine a modified standardized precipitation index for the Ping river in Northern Thailand. Environ. Asia 12(3), 32–42 (2019).

Kleyer, M. et al. Assessing species and community functional responses to environmental gradients: Which multivariate methods? J. Veg. Sci. 23(5), 805–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2012.01402.x (2012).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2018). https://www.R-project.org/

Guo, Y., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularized linear discriminant analysis and its application in microarrays. Biostatistics 8(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxj035 (2006).

Umwali, E. D. et al. Spatio-seasonal variation of water quality influenced by land use and land cover in lake muhazi. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 17376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96633-9 (2021).

Cole, L. J., Stockan, J. & Helliwell, R. Managing riparian buffer strips to optimize ecosystem services: A review. Agr Ecosyst. Environ. 296, 106891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106891 (2020).

Liu, S. et al. Risk assessment of soil heavy metals associated with land use variations in the riparian zones of a typical urban river gradient. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 181, 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.04.060 (2019).

Camara, M., Jamil, N. R. & Abdullah, A. F. B. Impact of land uses on water quality in Malaysia: A review. Ecol. Process. 8(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-019-0164-x (2019).

Shi, P. et al. Response of nitrogen pollution in surface water to land use and socialeconomic factors in the Weihe river watershed, Northwest China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 50, 101658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101658 (2019).

Miranda, L. S., Deilami, K., Ayoko, G. A., Egodawatta, P. & Goonetilleke, A. Influence of land use class and configuration on water-sediment partitioning of heavy metals. Sci. Total Environ. 804, 150116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150116 (2022).

Canet-Martí, A. et al. Comparison of simple models for total nitrogen removal from agricultural runoff in FWS wetlands. Water Sci. Technol. 85(11), 3301–3314. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2022.179 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Ecological wetland paradigm drives water source improvement in the stream network of Yangtze river Delta. J. Environ. Sci. 110, 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2021.03.015 (2021).

Feng, Z. et al. Analysis of water quality indexes and their relationships with vegetation using self-organizing map and geographically and temporally weighted regression. Environ. Res. 216, 114587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.114587 (2023).

Bai, Y., Zhao, Y., Huang, L., Shen, D. & Sun, G. Numerical simulation of velocity distribution and pollution retention in flexible submerged vegetated channel. J. Hydrol. 626, 130265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2023.130265 (2023).

Karimi, K., Miller, J. W., Sankarasubramanian, A. & Obenour, D. R. Contrasting annual and summer phosphorus export using a hybrid bayesian watershed model. Water Resour. Res. 59(1). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR033088 (2023). e2022WR033088.

Pinto, U., Rao, S., Phillip Svozil, D., Wright, A. & Goonetilleke, A. Understanding the role of land use for urban stormwater management in coastal waterways. Water Res. 245, 120658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2023.120658 (2023).

Ahmad, W. et al. Impact of land use/land cover changes on water quality and human health in district Peshawar Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 16526. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96075-3 (2021).

UMassAmherst Fact Sheets, Massachusetts Water Watch Partnership (2016). https://www.umass.edu/mwwp/resources/factsheets.html#:~:text=If%20these%20inorganic%20forms%20of,nitrogen%20can%20limit%20algae%20growth

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Thailand, for providing the water quality data and the Land Development Department for the land use data essential to this study. We also extend our appreciation to the Department of Water Resources Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, and Tsinghua University for their technical support and insightful discussions throughout the research process. Finally, we acknowledge the invaluable feedback provided by our reviewers, whose suggestions greatly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund, Chulalongkorn University (No. 6641/2566).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kwanchai Pakoksung: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Nantawoot Inseeyong: Validation, Investigation. Nattawin Chawaloesphonsiya: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Patiparn Punyapalakul: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Pichet Chaiwiwatworakul: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Mengzhen Xu: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Pavisorn Chuenchum: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The authors undertake that this article has not been published in any other journal and that no plagiarism has occurred.

Consent to participate

The authors agree to participate in the journal.

Consent to publish

The authors agree to publish in the journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pakoksung, K., Inseeyong, N., Chawaloesphonsiya, N. et al. Seasonal dynamics of water quality in response to land use changes in the Chi and Mun River Basins Thailand. Sci Rep 15, 7101 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91820-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91820-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating the reliability, resilience, and vulnerability of water resources: the impact of minimum, maximum, environmental flows, and water quality

Applied Water Science (2026)

-

Vanishing waters and growing settlements: tracking the impact of land use land cover changes on the Lower Mara River Basin

Wetlands Ecology and Management (2025)

-

Analyzing land use change and surface water dynamics (1990–2020) in the upper Bhima River basin using Google Earth engine

Discover Water (2025)

-

Toward Intelligent Water Monitoring: Benchmarking AutoML and Deep Learning for WQI Prediction in the Indus River

Earth Systems and Environment (2025)

-

Effect of land use, geology, and seasonality on hydrogeochemical baseline variations in a watershed impacted by human activities in the eastern Amazon

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2025)