Abstract

Low-resolution images present significant challenges for age estimation in real-world. Current models are unsuitable for low-resolution scenarios as they lose crucial details and weaken feature representations, leading to significant performance degradation. To address the limitation, we propose the Multi-Grained Pooling Network (MGP-Net), a novel architecture that effectively captures multi-grained information during the downsampling process, preserving essential features for age estimation. Additionally, we introduce a simple random shuffle degradation model to simulate realistic low-resolution images, ensuring robust training and evaluation. Experimental results on the Morph \(\text {II}\), FG-NET, and CLAP2015 datasets demonstrate that the proposed method achieves competitive performance compared to the state-of-the-art models which trained with high-resolution images, showcasing its robustness and applicability in real-world low-resolution scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age estimation from facial images has significant applications in various domains, including security, surveillance, personalized services, and demographic analysis1,2,3. Recent advances in deep neural networks have greatly improved the ability of neural networks to extract and represent age-related facial features. However, the performance of these models is often insufficient in the real world, primarily due to the resolution gap between training and inference. Figure 1 illustrates this challenge: Fig. 1a illustrates low-resolution images that may be encountered during inference. Even when the faces are cropped from the same image, variations in spatial position within the image can result in differences in clarity. Figure1b shows that facial images cropped from high-resolution images during the training phase, preserving detailed facial features.

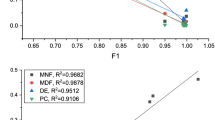

This discrepancy becomes even more pronounced in scenarios where inference images are resized to match standard resolutions (e.g., 224 \(\times\) 224). As shown in Fig. 2a, resizing a low-resolution image (e.g., 64 \(\times\) 64) results in a loss of high-frequency details and introduces distortions. Figure 2b highlights the performance gap using the vanilla ResNet-184 and its modified version trained on Morph \(\text {II}\). In 224 group, the modified model, trained by resizing low-resolution images (64 \(\times\) 64 to 224 \(\times\) 224), suffers a significantly degrades the model performance from 2.41 to 2.75 Mean Absolute Error (MAE). In 64 group, when trained directly on vanilla model, the downsampling layers reduce the activation map size. This reduction leads a decline in performance.

The recent trend towards larger models and higher-resolution inputs in computer vision further exacerbates this issue. Modern architectures, including large Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)5,6,7 and Transformer-based models8,9, are often designed for high-resolution images ranging from 224 \(\times\) 224 to 384 \(\times\) 384 pixels. These models effective for high-resolution tasks are suboptimal for low-resolution tasks in the real world.

To address this challenge, we re-evaluate the design of conventional deep learning models and downsampling layer, we introduce the Multi-Grained Pooling Network (MGP-Net), a purely CNN-based architecture optimized for low-resolution age estimation. MGP-Net reimagines conventional downsampling processes by introducing Multi-Grained Pooling (MGPool), which captures multi-grained information, enabling better retention of critical features. Inspired by ConvNeXt5, our network uses standard 3 \(\times\) 3 convolutions to construct our model.

Additionally, we propose a simple degradation model that simulates real-world images by applying shuffle order sequence of blur, noise, and downsampling. This degradation model effectively replicates the challenges of low-resolution images in real-world applications. Our contributions are summarized as follows:

-

We propose a MGPool for low-resolution images in age estimation tasks, which preserves feature information more effectively during downsampling process.

-

We propose a simple degradation model that incorporates blur, noise, and downsampling to simulate low-resolution in the real world.

-

We present MGP-Net, a CNN-based architecture that follows modern neural network design principles. MGP-Net demonstrates its effective performance on age estimation tasks and image classification in low-resolution scenarios.

Sample images with different resolutions and their impacts on model performance. (a) Different resolution images; (b) illustrates the impact of resolution changes. In 224 group, “modified” refers to images resized from 64 yo 224; In 64 group, “modified” indicates a reduction in downsampling layers from 5 to 3.

Related work

Age estimation

Age estimation is a hot topic in computer vision, with methodologies generally categorized into four main approaches: regression, classification, ordinal regression, and distribution learning. Regression methods treat age as a continuous variable and utilize various machine learning algorithms to predict age10,11. In classification methods, age is treated as independent categories, similar to traditional classification tasks in deep learning12,13. Ordinal regression methods, also called ranking methods, focus on capturing sequential relationships among different ages14,15,16,17,18. Distribution learning methods treat age labels as a distribution rather than as fixed values19,20,21.

In the deep learning era, exploiting discriminative feature of facial image is the big challenge for age estimation. Some papers usually adopt CNNs such as VGG22 and ResNet4 as the backbone to extract age feature. Rothe et al.13 used weights of the softmax to optimize age feature extraction. Pan et al.2 utilized VGGNet as backbone, and proposed mean-variance loss to improve the feature extraction. Deng et al.21 proposed progressive margin loss to help feature extraction avoid the influence of long-tailed distribution in age datasets. Chen et al.23 designed the Delta Age AdaIN operation to obtain the difference of age feature. Shou et al.24 used a masked graph convolutional network to capture structure information.

The parameters of deep CNN models are huge and not suitable for real-world applications. Therefore, compact networks are introduced into age estimation task1,3,25. These lightweight architectures reduce computation, making them more practical for deployment. However, despite these improvements, real-world applications should also account for the challenges posed by low-resolution images, which significantly impact the quality of extracted features and the overall model performance. This remains an underexplored area, highlighting the need for further research to bridge this gap.

The overall framework of MGP-Net comprises a degradation model, the MGP-Net backbone, and a classifier. The degradation model employs a random shuffle degradation strategy to downsample high-resolution (HR) images to low-resolution (LR) images, then fed into the MGP-Net backbone to extract features. Finally, the classifier predicts the age based on these features.

Low-resolution

Early researchers’ attempts to address the challenge of low-resolution images by introducing super-resolution techniques. Cai \(et\ al.\) explored enhancing the fine-grained features in super-resolution images to improve performance in low-resolution classification tasks26. Building on this approach, Zhu \(et\ al.\) proposed the Attention-aware Perceptual Enhancement Nets (APEN), which generates super-resolution images from low-resolution images to enhance the performance of model27. Huang et al.28 adopted knowledge distillation for low-resolution images, they proposed Feature Map Distillation framework, the teacher network used high-resolution features to guide the student network which fed the low-resolution images28. Although this approach reduces model parameters and improves deployability, it has two drawbacks: (i) Hyperparameter sensitivity. The distillation process requires careful tuning, which makes training more complex and time-consuming. (ii) Generalization challenges. The student model may overfit the teacher’s output. Therefore, some researchers focus on low-resolution architecture. Sunkara et al.29 proposed SPD-Conv, which replaces traditional downsampling layers with a space-to-depth module, reducing information loss during downsampling30. Gu et al.31 proposed a Multi-Granular Information-Lossless model for pose estimation, and show its effectiveness in low-resolution images classification task.

We notice that while these approaches benefit from the space to depth module, there are still limitations: (i) space to depth reduces the loss of image information in space dimension, but cause the information redundancy in the channel dimension; (ii) lack the efficiency of the feature representation; (iii) the effect of degraded images is not considered. To address these issues, we propose MGPNet to obtained multi-grained information and enhance the effective representation of facial age features in low-resolution images. In addition, we propose a simple degradation model to simulate real-world low-resolution images, enhancing the generalization of the model.

Methods

Figure 3 gives the overview of our approach, which includes the degradation model and Multi-grained pool (MGPool). We first state the problem, and introduce the overall framework of our MGPNet, then introduce the details of degradation model and MGPool.

Problem formulation

In this study, we define the age estimation problem by considering a dataset containing facial images \(X = \left\{ x_{i}|i = 1..N\right\}\) and \(y_{i} \in Y\) where \(y_{i}\) denote the ground truth age, and N is the number of images. F denote the function, which is used to predict the age from a single face image x, \(\hat{y} = F(x)\), where \(\hat{y}\) denote the predicted age. We employ the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to quantify the discrepancy between predicted age and the ground truth age. It provides a direct measure of prediction accuracy, with lower values indicating predicted age is more close to the ground truth ages.

According to previous work2,21, we also used the \(\epsilon\)-error to measure the performance on the CLAP2015 dataset32, which defined as:

Where \(\hat{\sigma }\) indicate the standard deviation value. The age labels in CLAP2015 datasets are based on apparent age estimates provided by multiple annotators. A smaller \(\epsilon\)-error indicates that the model’s predictions align closely with the perceived age distribution, reflecting higher confidence.

The Cumulative Score (CS)33 evaluates the percentage of predictions that fall within a specified acceptable error range (T) of the ground truth ages, which defined as \(cs = \frac{N_i}{N} \times 100\%\), where \(N_i\) is the number of images when \(|\hat{y_i} - y_i| \le T\), T is a threshold distance. In this paper, we set \(T=5\), meaning that a predicted age is considered correct if the distance between the predicted age and the ground truth age does not exceed 5 years.

In age estimation tasks, age should not be treated as isolated individual values, but rather as a sequence of related numbers. Following the approach proposed by Diaz et al.16, we assume \(D = \left\{ d_{1},d_{2},...,d_{k}\right\}\) be the K rank ages. To capture the variations between different ages, we employ a distance metric to measure similarity: closer ages are considered more similar, thereby assigning a greater weight. Conversely, as the age gap increases, the weight decreases. We employ Softmax function to compute the rankings of age, defined as:

where \(\phi (r_{j},r_{i})\) denote the L1 distance of \(r_{j}\) and \(r_{i}\), which is defined as:\(\phi (r_{j},r_{i}) = |r_{j} - r_{i}|\). Compared with one-hot label, model can learn the information of ordinal age via soft label. Hence, we define the soft label loss \(L_{sc}\) as:

Overall framework

The overall framework of our proposed model is illustrated in Fig. 3. First, we feed the image into degradation model to simulate real-world low-resolution images; Then, the degraded images are input into the backbone to extract the feature; Finally, the model is optimized by SORD loss16 and output the age label. The details are given below.

Following the ConvNeXt5 guidelines, we adjust the stage ratio and adopt fewer activation function, while retaining Batch Normalization (BN) and ReLu. Our model is built on ResNet4 basic block, and we combine channel attention and spatial attention to effectively improve feature representation. To efficiently utilize channel information, we integrate the ECA module34 in CBAM35 to replace the SE module. The details of MGPBlock as shown in Fig. 3 MGPBlock.

The model architecture follows a four-layer design, similar to ResNet, where the depth is defined as \(N (N_1, N_2, N_3, N_4)\). The N of ResNet-18 and Resnet-50 are N(2, 2, 2, 2) and N(3, 4, 6, 3), respectively. Following ConvNeXt5 and Swin Transformer9, the ratio of lightweight networks is (1, 1, 3, 1). Therefore, we adopt N(2, 2, 6, 2) for our model, and the channel number is set (64, 128, 256, 512) in each layer, ensuring a balance between model capacity and computational efficiency. Except for the first layer, MGPool is used for downsampling in the subsequent three layers.

Multi-grained pool

Downsampling is a widely used method in deep learning. Traditional downsampling such as Avgpool, Maxpool, and convolutional stride. These downsampling layers can obtain effective feature representation while reducing computational cost. However, they are not suitable for low-resolution images which lack sufficient redundant pixel information to learn discriminative features.

Consider a local region R in an activation map a with dimensions \(C \times H \times W\), where C is the number of channels, H and W are the height and width, respectively. For clarity, we simplify notation by omitting the channel dimension. For a pooling filter size of \(k \times k\), we define \(R = k^2\), and the output of the pooling operation as \(\tilde{a}_{R}\). SoftPool36 is a new downsampling pool which based on the large activation values while retaining information from weaker activations, offering a smooth transition in the regions, define as:

The Generalized-mean pool (GeM)37 introduces a parameter p to non-linearly model features, which is also a generalized form of Avgpool and Maxpool. While GeM offers flexibility, it still requires tuning the parameter p for optimal performance in different datasets and tasks, which may be impractical in diverse application scenarios. To learn different fine details of feature, we design a multi generalized-mean pool (MGeMpool), which define as:

Inspired by efficient channel attention34, we propose the Multi-Grained Pool (MGPool), which gets a balance between retaining informative details and enhances feature representation. Figure 4 illustrates the MGPool mechanism. The input of the MGPool is feature maps from convolutional layers. To capture diverse granularity information, we adopt SoftPool and MGeMPool as downsampling operation. The results are concatenated along the channel axis. However, we notice that simple concatenate cannot improve feature representation. Therefore, we introduce a random channel shuffle to enhance the channel interaction between different granularity features. As show in Fig. 4, we use Global Average Pooling (GAP) to generate channel information, and then fed in 1D convolution with kernel size of k to improve cross-channel interaction and refine feature representation.

Where \(f_{cs}\) denotes the channel shuffle operation. \(\sigma\) denotes the sigmoid function, \(g(x) = \frac{1}{HW}\sum ^{H,W}_{i=1,j=1}x_{ij}\) indicates the Global Average Pool, \(C1D_k\) denotes the 1D convolution with the kernel size of k. And we find that when p set 1,3,and \(\infty\), the model achieves better performance. When \(p=1\) is equal to AvgPool, and \(p=\infty\) is equal to MaxPool.

Then use a \(1 \times 1\) convolution to reduce the number of channels to match the input feature maps. And then fed the feature map into subsequent network. The MGPool can minimize the feature information loss and effectively learn the cross-channel interaction from different granularities.

Degradation model

Our degradation model simulates real-world images by incorporating three primary factors: blur, downsampling, and noise, inspired by recent studies38,39. The high-resolution image h initially undergoes convolution with a blur kernel k, followed by downsampling at a scale factor r, and finally, noise n is added. To further mimic real-world scenarios, The process includes JPEG compression, RGB shift, and ISO noise, encapsulating the sequence in the degradation function D:

Where \(\otimes\) denotes convolution, \(\downarrow\) represents the downsampling operation. \(N_{JPEG}\) denotes the JPEG compression noise, and l indicates the low-resolution images.

Blur

Both isotropic and anisotropic Gaussian filters are applied, following the BSRGAN39 settings, which achieve a wide range of blur effects.

Downsampling

We employ various algorithms-bilinear, nearest neighbor, bicubic, and area interpolation to generate low-resolution images. A random selection from these methods is used for each downsampling operation to introduce variability.

Noise

We introduce Gaussian noise, which follows a normal distribution across RGB channels, and Poisson noise to mimic sensor noise. Additionally, JPEG compression is applied with the compression quality is modulated by a quality factor q ranging from 0 to 100.

To better simulate the complexity of real-world image degradation, we employ a simple random shuffle strategy. As shown in Figure 3, this strategy allows us to generate a diverse set of low-resolution images using various degradation processes.

Results

In this section, we describe the experimental setup, which is divided into four main parts. First, we provide an overview of the datasets commonly used in age estimation. Then we introduce some details of experiments. Following this, we compare our model with the state-of-the-art models across three datasets. Finally, a series of ablation studies were conducted to evaluate the performance of our model. The IMDB-WIKI dataset was only pre-trained in our experiments.

Datasets

IMDB-WIKI

This is the largest real-world facial dataset, containing 523,051 images with ages ranging from 0 to 100. Due to significant noise in the dataset, we clean it and use approximately 330,000 images for pre-training, following common practices13.

Morph II

Recognized as a benchmark for age estimation, Morph \(\text {II}\) comprises 55,134 images from 13,167 subjects, with ages ranging from 16 to 7740. We adopt two testing protocols: a five-fold random split (RS) and a five-fold subject-exclusive (SE) protocols, ensuring no identity overlap between training and testing dataset in SE protocol2,21,41.

FG-NET

An early dataset for age estimation, FG-NET includes 1,002 images from 82 subjects, there are significant variations in lighting and expression42. The ages range from 0 to 69. We evaluate our model using the leave-one-person-out (LOPO) protocol21,43.

CLAP2015

CLAP2015 contains 4,691 images annotated with the average age determined by at least 10 independent annotator32. We train and validate our model on the designated subsets and test performance on the test subset.

First, we use MTCNN44 to detect and crop faces, resizing image to 256\(\times\)256. The IMDB-WIKI dataset is only used for pre-training. We augment data with horizontal flipping and random erasing, the input size is 3 \(\times\) 64 \(\times\) 64. The weight decay is set 0.00005 and 0.05, the initial learning rate is set 0.00005 and 0.004 for AdamW45, respectively. The learning rate is adjust via CosineAnnealingLR46. Models are trained with PyTorch on Tesla V100 GPU.

Results in age estimation

Comparisons on Morph II

Table 1 shows the results of our MGP-Net and other state-of-the-art models using the Random Split (RS) and Subject-Exclusive (SE) protocols. Each model is trained twice: once from scratch and once pre-trained on IMDB-WIKI dataset. With IMDB-WIKI pre-training, MGP-Net achieve MAE of 2.28 and 2.86 under RS and SE protocols, respectively. Additionally, it achieves Cumulative Score (CS(5)) of 91.44 and 96.67 under RS and SE protocols with pre-training, respectively. Compared with C3AE1, which uses the same image size, our model achieves better performance. Under RS protocol, our model lower 0.47 MAE than C3AE with IMDB-WIKI pretraining. MGP-Net and DAA23 are both competitive models for age estimation, with DAA showing slightly better MAE performance. Compare to MCGRL24, our results demonstrate certain advantages. However, it is important to note that MCGRL combines CNN and GCN architectures, whereas our model uses a purely CNN-based structure. However, our model is more efficiency, particularly with lower resolution images and fewer parameters, makes it suitable for real-world applications where computational resources were limited. Additionally, compare to DAA under the same settings and input size, our MGP-Net outperformed DAA in both performance and inference speed without pre-training, as shown in Table 8. This further demonstrates that our model is optimized for low-resolution images while effectively balancing performance and inference speed.

Comparisons on FG-NET

As shown in Table 2, we extend our comparisons to the FG-NET dataset. Pre-training MGP-Net on the IMDB-WIKI dataset significantly improved its performance on this small dataset. With pre-training, MGP-Net achieved an MAE of 2.28 and a CS(5) of 90.33. Compared to PML21 and DAA23, which lead in MAE performance on FG-NET, our model was slightly higher than 0.12 and 0.09 MAE, respectively. However, our model has fewer parameters and input low-resolution images, making it more efficient. In general, MGP-Net achieves competitive performance on the FG-NET dataset.

Comparisons on CLAP2015

The results on the CLAP2015 dataset32 are summarized in Table 3. With pre-training on the IMDB-WIKI dataset, MGP-Net achieved an MAE of 3.140 and an \(\epsilon -error\) of 0.276. The CLAP2015 dataset is known for its complexity, and the challenge is amplified when training on low-resolution images. Several previous methods employed additional tricks to improve performance. For example BridgeNet10 uses 10 flipped images to measure the predicted age. DEX13 and AGEn47 adopt Ensemble Voting Technique to improve the model performance. NMW17 conducts multiple iterations of training to refine age prediction, increasing computational cost. Without using these tricks, our proposed method achieves competitive performance, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling low-resolution images in a challenging dataset like CLAP2015.

Results in image classification

To verify the universality of our model, we conduct recognition experiments on Tiny-ImageNet dataset51, which is a subset of the ImageNet-1000 dataset. Tiny-ImageNet contains 200 classes, and each class has 500 images for training, 50 images for validation and test, respectively. The resolution of the Tiny-ImageNet dataset is 3 \(\times\) 64 \(\times\) 64, and there are lack of test data label. So we used validation data to evaluate our model performance, and we adopted Top-1 accuracy as the metric.

Training

We trained our MGPNet on Tiny-ImageNet dataset with AdamW optimizer, and the training settings were similar to the ones used in Morph \(\text {II}\), except for batch size is 100 and training epoch is 200 epochs.

Results

Table4 shows the results of different models on low-resolution dataset. We first compare our model with ResNet-184, which are the most common benchmarks. With significantly fewer parameters than ResNet-18, we are 3.90% higher in Top-1 accuracy. Compared with other models with more parameters, such as WaveMix52, ResNet50-SPD29 and ResNext-5053, our model still outperforms them in performance when the number of parameters is significantly less than these models.

Ablation study

In this subsection, we evaluate the effectiveness of our design choices through ablation studies conducted on the Morph \(\text {II}\) dataset. All models are trained from scratch under same settings. Table 5 shows the results of different modules of MGPool. For MGeMPool, p indicates the norm of the Eq. (6), and when \(p=1\) equals AvgPool and \(p=\infty\) equals MaxPool. We aim to explore the feature learning capabilities of pooling with different values of p. Additionally, to evaluate the effectiveness of different random channel shuffle attention groups, we set g range from 1 to 8, where \(g = 1\) means that the random channel shuffle does not use.

As shown in Table 5, we compare four variants of downsampling pool. Concatenating three types pools, when \(p=1\),\(p=3\) and \(p=\infty\), shows better performance over other configurations, achieves 2.50 MAE and 89.48 CS(5) on Morph \(\text {II}\) dataset. Further enhancing channel interaction with the channel shuffle and the ECA module (ECSA), when \(g=4\) our MGPool achieves better performance, the MAE is 2.46 and CS(5) is 90.15.

To validate the impact of channel attention and spatial attention modules on our model, we conduct additional experiments (Table 6). The ECA module34 outperforms the SE module55 in this study, achieving 2.43 MAE, which is better than SE’s 2.44. Although, using both channel attention and spatial attention together did not improve the MAE, it improves the CS(5) by 0.25 compare to using only ECA module. We also evaluate the effect of the trigger probability p of the degradation model. The results indicate that setting \(p = 0.2\), the degradation model achieves better performance, improving the MAE by 0.06 compare to not using the degradation model.

According to Table 7, we employ ResNet-18 as the backbone to explore the performance of various downsampling layers. Notably, AvgPool and SoftPool achieve better performance compare to the vanilla and MaxPool. Using the same backbone, MGPool demonstrates superior performance by reducing the MAE by 0.03 compare to SoftPool. Combining the SoftPool and MGeMPool, MGPool creates a more comprehensive representation of features. The channel shuffle operation enhances feature interactions across different granularities, leading to improve cross-channel representations. By employing MGP-Net as the backbone architecture, the performance is further improved, underscoring the efficacy of our proposed model.

To evaluate the performance of our model on low-resolution images of different sizes, we conduct a comprehensive comparison with DAA (Table 8). Using the Morph \(\text {II}\) dataset under the same settings, we compare performance at image resolutions of 32 \(\times\) 32, 64 \(\times\) 64, and 128 \(\times\) 128 without pre-training. The results indicate that our model performs better than DAA. Additionally, inference speed tests reveal that our model is faster than DAA. To further assess the generalization capability of MGP-Net and the effectiveness of the degradation models when encounter degraded images. We set \(p = 0.2\) and preprocess the dataset using the degradation model. The experiments show that using degraded images decreases the performance for both MGP-Net and DAA compare to the original dataset. However, the degradation model improves the performance of both models, and DAA shows a more significant improvement. These findings indicate that the MGP-Net and degradation model are effective and contribute to improving robustness in handling low-resolution and degraded images.

Discussion

The performance of age estimation models is heavily influenced by the quality and resolution of the input facial images. In real-world applications, low-resolution images lose critical facial details, making it challenging for models to learn discriminative age features. This study addresses these challenges by introducing MGP-Net and degradation model.

Figure 5 shows some positive and negative heatmaps of age estimation results on Morph \(\text {II}\), FG-Net, and CLAP2015. These heatmaps are generated by the Grad-CAM++56. We can see that the proposed approach performs robust for young, middle-aged people. For kids and elderly, there are biases due to unbalanced dataset. Besides degraded images, different facial gestures also impact prediction accuracy in age estimation tasks. Heatmap visualization reveals that the model focuses on the smooth forehead and chin of young individuals. In contrast, for adults and the elderly, the model primarily attends to the eye-nose triangle area, where age-related features such as wrinkles and structural changes are more pronounced. For negative examples, the model’s performance decreases notably in cases involving side-profile images or blurring, both of which obscure critical facial details. Furthermore, some negative examples reveal that even when the model focuses on the correct regions, it still makes wrong predictions. This suggests that the learned features may lack sufficient discriminative power to accurately estimate age, particularly when working with low-resolution images that inherently lack fine-grained details.

Our findings indicate that low-resolution images adversely affect the performance of age estimation models. High-resolution images provide rich details, allowing models to extract enough discriminative age features through downsampling process. In contrast, low-resolution images lack these details, making it difficult for models to capture essential features. This degradation in image quality leads to a decrease in model performance, as evidenced by increased MAE and reduced CS in our experiments. Through the reviews of image quality57,58,59, we find that for low-resolution images, besides simulating degradation processes, image restoration techniques can be employed to reconstruct high-quality images, such as diffusion model and GAN60,61,62,63.

Heatmaps of age estimation results generated by Grad-CAM++. (a) MORPH \(\text {II}\), (b) FG-NET, (c) CLAP2015. The top twos rows show some positive examples, and the third row shows some negative examples. Note that, red regions in heatmaps corresponds to high score for age estimation, and numbers below each image show the ground truth age and predicted age, i.e., ground truth age (predicted age).

To tackle these challenges, we proposed MGP-Net, which integrates a Multi-Grained Pooling (MGPool) and a degradation model into the age estimation framework. Our model still has room for improvement. First, MGPool increases computational complexity due to the extraction of multi-grained features. This can increase training and inference times, which may be a concern for time-sensitive applications or resource-constrained devices. Second, the degradation model can also increase the computation and training time. Additionally, as a simple simulation, it may not fully replicate the real-world images. This limits its ability to generalize to more complex or diverse degradation scenarios. Third, our current implementation is specifically designed for images with resolution of 64 \(\times\) 64. While this resolution is representative of low-resolution scenarios, it does not encompass all possible low-resolution images encountered in practice. Although we have demonstrated the effectiveness of our model on various image sizes, 64 \(\times\) 64 remains our primary input size, which may restrict its applicability to other resolutions.

Moreover, there is an extension of our MGP-Net that has achieved better performance on low-resolution classification tasks. This suggests that the MGPool has general applicability across various low-resolution scenarios.

Through reviews of image quality57,58,59, we find that for low-resolution images, besides simulating degradation processes, image restoration techniques can be employed to reconstruct high-quality images, such as diffusion model and GAN60,61,62,63,64. In future work, we will compare the effects of the two methods on model performance and further quantify how varying degrees of degradation affect the model.

Conclusion

This paper proposed MGP-Net effectively addresses the challenges associated with low-resolution age estimation by achieving a balance between model parameters and performance. Its superior results on the Morph \(\text {II}\), FG-NET, and CLAP2015 datasets, highlight its potential for real-world applications. In future work, we will focus on optimizing the computational efficiency and improving feature representation to handle a wider range of image resolutions in real-world applications.

Data availability

The datasets utilized in this paper were from the open source IMDB-WIKI dataset, Morph \(\text {II}\) dataset, CLAP2015 dataset, FG-NET dataset and Tiny-ImageNet dataset. These datasets can be found at the following website.

\(\bullet\) IMDB-WIKI: https://data.vision.ee.ethz.ch/cvl/rrothe/imdb-wiki/

\(\bullet\) Morph \(\text {II}\): https://uncw.edu/myuncw/research/innovation-commercialization/technology-portfolio/morph

\(\bullet\) CLAP2015: https://competitions.codalab.org/competitions/4081

\(\bullet\) FG-NET: https://yanweifu.github.io/FG_NET_data/

\(\bullet\) Tiny-ImageNet: https://www.kaggle.com/c/tiny-imagenet/data

References

Zhang, C., Liu, S., Xu, X. & Zhu, C. C3ae: Exploring the limits of compact model for age estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 12587–12596 (2019).

Pan, H., Han, H., Shan, S. & Chen, X. Mean-variance loss for deep age estimation from a face. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 5285–5294 (2018).

Yang, T.-Y., Huang, Y.-H., Lin, Y.-Y., Hsiu, P.-C. & Chuang, Y.-Y. Ssr-net: A compact soft stagewise regression network for age estimation. In IJCAI. Vol. 5. 7 (2018).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 770–778 (2016).

Liu, Z. et al. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 11976–11986 (2022).

Ding, X., Zhang, X., Han, J. & Ding, G. Scaling up your kernels to 31x31: Revisiting large kernel design in cnns. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 11963–11975 (2022).

Ding, X. et al. Unireplknet: A universal perception large-kernel convnet for audio video point cloud time-series and image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 5513–5524 (2024).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) (2021).

Li, W. et al. Bridgenet: A continuity-aware probabilistic network for age estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1145–1154 (2019).

Shen, W. et al. Deep regression forests for age estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2304–2313 (2018).

Levi, G. & Hassner, T. Age and gender classification using convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. 34–42 (2015).

Rothe, R., Timofte, R. & Van Gool, L. Deep expectation of real and apparent age from a single image without facial landmarks. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 126, 144–157 (2018).

Niu, Z., Zhou, M., Wang, L., Gao, X. & Hua, G. Ordinal regression with multiple output cnn for age estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4920–4928 (2016).

Zang, H.-X. et al. Ages of giant panda can be accurately predicted using facial images and machine learning. Ecol. Inform. 72, 101892 (2022).

Diaz, R. & Marathe, A. Soft labels for ordinal regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 4738–4747 (2019).

Shin, N.-H., Lee, S.-H. & Kim, C.-S. Moving window regression: A novel approach to ordinal regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 18760–18769 (2022).

Lee, S.-H., Shin, N. H. & Kim, C.-S. Geometric order learning for rank estimation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 35, 27–39 (2022).

Geng, X. Label distribution learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 28, 1734–1748 (2016).

Gao, B.-B., Zhou, H.-Y., Wu, J. & Geng, X. Age estimation using expectation of label distribution learning. In IJCAI. 712–718 (2018).

Deng, Z. et al. Pml: Progressive margin loss for long-tailed age classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.02140 (2021).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Chen, P. et al. Daa: A delta age Adain operation for age estimation via binary code transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 15836–15845 (2023).

Shou, Y., Cao, X., Liu, H. & Meng, D. Masked contrastive graph representation learning for age estimation. Pattern Recognit. 158, 110974 (2025).

Zang, H.-X., Su, H., Qi, Y. & Wang, H.-K. A compact soft ordinal regression network for age estimation. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC). 3035–3041 (IEEE, 2021).

Cai, D., Chen, K., Qian, Y. & Kämäräinen, J. Convolutional low-resolution fine-grained classification. arXiv:abs/1703.05393 (2017).

Zhu, X., Li, Z., Li, X., Li, S. & Dai, F. Attention-aware perceptual enhancement nets for low-resolution image classification. Inf. Sci. 515, 233–247 (2020).

Huang, Z. et al. Feature map distillation of thin nets for low-resolution object recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 1364–1379 (2022).

Sunkara, R. & Luo, T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: A new cnn building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. 443–459 (Springer, 2022).

Sunkara, R. & Luo, T. No more strided convolutions or pooling: A new cnn building block for low-resolution images and small objects. In ECML/PKDD (2022).

Gu, Z., Zhao, Z.-Q., Shen, H. & Zhang, Z. Focus on low-resolution information: Multi-granular information-lossless model for low-resolution human pose estimation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12247 (2024).

Escalera, S. et al. Chalearn looking at people 2015: Apparent age and cultural event recognition datasets and results. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops. 1–9 (2015).

Guo, G., Mu, G., Fu, Y. & Huang, T. S. Human age estimation using bio-inspired features. In 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 112–119 (IEEE, 2009).

Wang, Q. et al. Eca-net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 11534–11542 (2020).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y. & Kweon, I. S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). 3–19 (2018).

Stergiou, A., Poppe, R. & Kalliatakis, G. Refining activation downsampling with softpool. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 10357–10366 (2021).

Radenović, F., Tolias, G. & Chum, O. Fine-tuning cnn image retrieval with no human annotation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 41, 1655–1668 (2018).

Wang, X., Xie, L., Dong, C. & Shan, Y. Real-esrgan: Training real-world blind super-resolution with pure synthetic data. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 1905–1914 (2021).

Zhang, K., Liang, J., Van Gool, L. & Timofte, R. Designing a practical degradation model for deep blind image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 4791–4800 (2021).

Ricanek, K. & Tesafaye, T. Morph: A longitudinal image database of normal adult age-progression. In 7th International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FGR06). 341–345 (IEEE, 2006).

Han, H., Otto, C., Liu, X. & Jain, A. K. Demographic estimation from face images: Human vs. machine performance. In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. Vol. 37. 1148–1161 (2014).

Lanitis, A., Taylor, C. J. & Cootes, T. F. Toward automatic simulation of aging effects on face images. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 24, 442–455 (2002).

Chang, K.-Y., Chen, C.-S. & Hung, Y.-P. Ordinal hyperplanes ranker with cost sensitivities for age estimation. In CVPR 2011. 585–592 (IEEE, 2011).

Zhang, K., Zhang, Z., Li, Z. & Qiao, Y. Joint face detection and alignment using multitask cascaded convolutional networks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 23, 1499–1503 (2016).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2019).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. In International Conference on Learning Representations (2017).

Tan, Z. et al. Efficient group-n encoding and decoding for facial age estimation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40, 2610–2623 (2017).

Han, H., Jain, A. K., Wang, F., Shan, S. & Chen, X. Heterogeneous face attribute estimation: A deep multi-task learning approach. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40, 2597–2609 (2017).

Tan, Z., Yang, Y., Wan, J., Guo, G. & Li, S. Z. Deeply-learned hybrid representations for facial age estimation. In IJCAI. 3548–3554 (2019).

Paplhám, J., Franc, V. et al. A call to reflect on evaluation practices for age estimation: Comparative analysis of the state-of-the-art and a unified benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1196–1205 (2024).

Le, Y. & Yang, X. Tiny imagenet visual recognition challenge. CS 231N(7), 3 (2015).

Jeevan, P., Viswanathan, K., Sethi, A. et al. Wavemix: A resource-efficient neural network for image analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.14375 (2022).

Xie, S., Girshick, R., Dollár, P., Tu, Z. & He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1492–1500 (2017).

Jeevan, P. & Sethi, A. Resource-efficient hybrid x-formers for vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision. 2982–2990 (2022).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 7132–7141 (2018).

Chattopadhay, A., Sarkar, A., Howlader, P. & Balasubramanian, V. N. Grad-cam++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV). 839–847. https://doi.org/10.1109/WACV.2018.00097 (2018).

Zhai, G. & Min, X. Perceptual image quality assessment: A survey. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 63, 1–52 (2020).

Min, X. et al. Screen content quality assessment: Overview, benchmark, and beyond. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 54, 1–36 (2021).

Min, X., Duan, H., Sun, W., Zhu, Y. & Zhai, G. Perceptual video quality assessment: A survey. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 67, 211301 (2024).

Song, W. et al. Expressive 3D facial animation generation based on local-to-global latent diffusion. In IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (2024).

Wang, W. et al. Low-light image enhancement based on virtual exposure. Signal Process. Image Commun. 118, 117016 (2023).

Deng, X., Zhang, C., Jiang, L., Xia, J. & Xu, M. Deepsn-net: Deep semi-smooth newton driven network for blind image restoration. In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2025).

Xu, H., Li, Q. & Chen, J. Highlight removal from a single grayscale image using attentive gan. Appl. Artif. Intell. 36, 1988441 (2022).

Huang, J.-H., Wang, H.-K. & Liao, Z.-W. Sir-srgan: Super-resolution generative adversarial networks with self-interpolation ranker. In BMVC. Vol. 52 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Scientific Research Projects of Scientific Research Institutes in Sichuan Province (No.2024JDKY0004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HX.Z. conceived the experiment(s), conducted the experiment(s) and wrote the manuscript; Q.X. analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, HX., Xiao, Q. Multi-grained pooling network for age estimation in degraded low-resolution images. Sci Rep 15, 8030 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91845-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91845-9