Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are secreted by most cell types and play a central role in cell-cell communication. These naturally occurring nanoparticles have been particularly implicated in cancer, but EV heterogeneity and lengthy isolation methods with low yield make them difficult to study. To circumvent the challenges in EV research, we aimed to develop a unique synthetic model by engineering bioinspired liposomes to study EV properties and their impact on cellular uptake. We produced EV-like liposomes mimicking the physicochemical properties as cancer EVs. First, using a panel of cancer and non-cancer cell lines, small EVs were isolated by ultracentrifugation and characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). Cancer EVs ranged in mean size from 107.9 to 161 nm by NTA, hydrodynamic diameter from 152 to 355 nm by DLS, with a zeta potential ranging from − 25 to -6 mV. EV markers TSG101 and CD81 were positive on all EVs. Using a microfluidics bottom-up approach, liposomes were produced using the nanoprecipitation method adapted to micromixers developed by our group. A library of liposome formulations was created that mimicked the ranges of size (90–222 nm) and zeta potential (anionic [-47 mV] to neutral [-1 mV]) at a production throughput of up to 41 mL/h and yielding a concentration of 1 × 1012 particles per mL. EV size and zeta potential were reproduced by controlling the flow conditions and lipid composition set by a statistical model based on the response surface methodology. The model was fairly accurate with an R-squared > 70% for both parameters between the targeted EV and the obtained liposomes. Finally, the internalization of fluorescently labeled EV-like liposomes was assessed by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry, and correlated with decreasing liposome size and less negative zeta potential, providing insights into the effects of key EV physicochemical properties. Our data demonstrated that liposomes can be used as a powerful synthetic model of EVs. By mimicking cancer cell-derived EV properties, the effects on cellular internalization can be assessed individually and in combination. Taken together, we present a novel system that can accelerate research on the effects of EVs in cancer models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are naturally secreted by most cell types and play a fundamental role in cell-to-cell communication. They transport a variety of biologically relevant cargo such as nucleic acids1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8and proteins9,10,11to distant cells. These nanoparticles are composed of a lipid bilayer membrane, and can be categorized based on their size, shape and origin12,13,14,15,16. They exhibit large variability in size, typically ranging from 50 to 1000 nm in diameter17. Their zeta potential, an indicator of their surface charge, is typically negative under physiological conditions and can vary depending on the pH and ionic composition of the medium. EVs are highly heterogenous populations18, making their study difficult. Indeed, there is growing research on EV subpopulations in terms of different sizes12,13,14,15,16, lipid profiles19,20, and surface markers21,22.

EVs are implicated in many diseases, with a particular focus on their role in cancer. Tumor-derived EVs contribute to the crosstalk between tumor cells and the microenvironment23,24and have been shown to play a major role in mediating metastasis, ranging from oncogenic reprogramming of recipient cells to formation of the pre-metastatic niche through priming of the microenvironment for colonization by circulating tumor cells25,26,27. Thus, EVs can modulate pro-tumor behavior, as shown in several tumor models28,29,30. Indeed, evidence now suggest that EVs released by cancer cells can transfer their oncogenic properties to recipient cells, which constitutes a novel mechanism of cancer dissemination23,31,32,33,34,35,36. This process occurs through uptake of EV cargo (pro-tumor cargo) by recipient cells. Moreover, the characteristics of EVs (such as size, lipid membrane content and zeta potential [measured via electrophoretic mobility]) have been proposed as mediators of uptake37,38. For these reasons, significant research has focused on characterizing EVs derived from cancer cells.

To exert their effect, EVs must first be internalized by recipient cells, where they can then transfer cargo and modulate cellular behavior35,36,39. However, the mechanisms involved in cellular uptake of EVs are still not fully understood: some EVs bind to specific receptors on target cells via clathrin or caveolin dependent pathways while others enter cells via pinocytosis and phagocytosis40,41. Apart from their surface moieties and lipid composition, the size and zeta potential are important factors when characterizing EVs42,43 but their role in cellular uptake has not been fully identified.

Research to determine the EV properties that promote uptake and downstream effects in cancer is limited by several hurdles. EV isolation methods require several purification steps, which are labor-intensive and time-consuming, require large scale cell culture and result in heterogeneous populations with low yields. Current sorting methods such as fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting (FAVS) are effective at dividing the populations by their protein contents or by size using tangential flow filtration (TFF)44, however, there is not a method for dividing EVs by their zeta potential or lipid composition.

Mimicking natural occurring EVs is an approach with the potential to address the challenges related to studying their characteristics independently and those related to heterogeneity and low45. Liposomes are artificial spherical-shaped structures made of lipid bilayers with a hydrophilic core46. They share characteristics with EVs including the capacity to encapsulate biomolecules. Liposomes provide a unique opportunity to control homogenous properties when compared to EVs, which are known for their high heterogeneity. In the last decade, micromixers have enabled the production of liposomes as well as the encapsulation in one single step in a continuous flow47,48,49,50. More recently, micromixers based on chaotic advection using curvilinear paths have shown to produce liposomes at high concentrations in a scalable way51,51. Micromixers offer the control of liposome size and allow to produce specific liposome populations, thus permitting the precise control of lipid, protein and cargo expression by modifying one parameter at a time (bottom-up approach). Bottom-up nanoparticle production offers a controllable and reproducible way of modulating liposome size and zeta potential via flow conditions and lipid composition52,53.

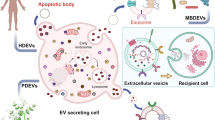

In this work, we sought to develop a synthetic model to mimic cancer EVs using liposomes, which could be used to study the effects of individual and combinations of EV characteristics on cellular uptake and downstream effects. Studying EVs in this simplified and homogeneous manner could be of considerable value in cancer research, allowing a deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved in tumor progression. To meet this goal, we characterized the physicochemical properties of a panel of cancer cell-derived EVs (Fig. 1A and 1B) and produced bioinspired liposomes by reproducing size and zeta potential using microfluidics and a statistical model (Fig. 1C and D). Finally, to assess internalization of the synthetic EVs, we observed their cellular uptake by non-cancer recipient cells (Fig. 1E and F). Our data demonstrate that cancer EVs can be modeled using liposomes and that physicochemical properties can be modulated to create different EV-like liposome populations. Moreover, we demonstrate that modulation of EV-like liposome composition impacts the rate of uptake by recipient cells. To our knowledge, this is the first study that uses a mathematical model to simulate and predict the physicochemical properties of EVs derived from cancer cells using a synthetic liposome system, thus opening new perspectives for the understanding and manipulation of these vesicles in discovery and therapeutic applications.

Graphical depiction of bioinspired liposome production process. (A) EV-isolation using ultracentrifugation, (B) EVs were characterized for size, zeta potential, polydispersity index (PDI) and concentration. (C) Liposomes were produced using the nanoprecipitation method adapted to micromixers. (D) Using a design of experiment (DoE) and response surface methodology (RSM), bioinspired liposomes with similar size and zeta potential as cancer EVs were produced. (E) Non-cancer cells representing the tumor microenvironment were treated with fluorescently-tagged bioinspired liposomes. Uptake was evaluated using live cell imaging (Incucyte). (F) Flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy were used to quantify uptake.

Methods

Cell culture

A panel of human cancer cells of different origins (carcinoma, melanoma) were used. A549, HeLa, and PC-3 cells were gifted to us by Dr. Lorenzo Ferri (McGill University). MP41 and fibroblast BJ cells were provided by Dr. Carlos Telleria (McGill University). OMM 2.5 and immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) were gifted by Dr. Vanessa Morales (University of Tennessee) and Dr. Peter Metrakos (McGill University), respectively. A549 and PC-3 cells were cultured in F-12 K medium (Wisent, QC, Canada) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.1% 10 Units/mL penicillin and 10 µg/mL streptomycin (30-001-CI, Corning, NY, USA). HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (319-075-CL, Wisent, QC, Canada) supplemented with 10% FBS and 0.1% 10 Units/mL penicillin and 10 µg/mL streptomycin (30-001-CI, Corning, NY, USA). MP41, BJs, and OMM 2.5 cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (35–077-CV, Corning, NY, USA), 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM Corning glutaGRO, 1 mM NaPyruvate, 0.1% 10 Units/mL penicillin and 10 µg/mL streptomycin (all from Corning), as well as 10 µg/mL insulin (4693124001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland). IHH were culture in DMEM 1x with/Avec 4.5 g/L Glucose with L-Glutamine & Sodium Pyruvate supplemented with 10% FBS. IHH cells were plated in Poly-L-lysine solution 0.01%, sterile-filtered treated plates. All cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere. Additional information is available in Table 1 (panel of human cells used for isolating EVs).

EV isolation and characterization

Cells were cultured until they reached 80% confluency. Then cell culture medium was replaced by medium supplemented with EV-depleted FBS. After an additional 24 h of incubation, cells were counted, and the supernatant (conditioned media) was collected. The supernatant was centrifuged at 500g for 10 min to remove cell debris, then at 2000g for 20 min, then removed and spun at 16,500 g for 20 min. Supernatants were transferred to new 26.3 mL polycarbonate tubes and ultracentrifuged at 120,000g for 70 min using 70 Ti rotor in Optima XE ultracentrifuge machine (Beckman Coulter). The crude EVs pellets were washed with 1XPBS at 120,000g for 70 min, resuspended in 500 µL 4% PBS and characterized (see below) as fresh samples. They were then stored in − 80 °C until use for protein extraction. All centrifuge steps were performed at 4 °C.

The average EV size and concentration were evaluated using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) (Nanosight NS300), and the polydispersity index (PDI) was calculated from NTA data as PDI = (Standard Deviation)2 / (Mean Particle Size)2. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Nanoparticle size and size distribution were also measured using dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique using the Zetasizer Nano S90 (Malvern, Worcestershire, United Kingdom), using low volume cuvettes (BRAND®) in the Zetasizer. Z-Average (mean hydrodynamic size), PDI, size distribution by intensity were recorded. The zeta potential was measured using the ZetaPlus instrument (Brookhaven Instrument Corp., Holtsville, NY).

Western blot

EVs and cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (PI89900, ThermoFisher) with Protease Inhibitor cocktail. Protein samples of EVs and cell lysates were analyzed for total protein concentration using the micro-BCA protein (Thermo Fisher Catalogue# 23235). Approximately 10 µg of total protein associated with EVs and 20 µg of whole cell lysate protein were loaded on 4–12% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX Stain-Free™ Protein Gels, (Biorad, catalogue #4568094) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (BioRad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris buffer saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST). The EV markers were probed with primary antibodies; rabbit monoclonal -TSG101 (1:1000, abcam, ab125011), rabbit polyclonal Syntenin (1:1000, abcam ab19903), rabbit monoclonal CD81 (1:1000, abcam, ab109201). Membranes were washed in TBST at least 5 times every 10 min and were treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies anti-rabbit HRP (1:10000, Cell Signaling, 7074 S). Membranes were developed using ECL prime Western blot detection (GE healthcare) and visualized using the ChemiDocTM XRS + System (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

20 µl of EVs were deposited onto freshly negative glow discharged carbon film 200 Mesh cu TEM grids (agar Scientific) for 30 min. The EVs were negatively stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate and observed with a FEI Tecnai TM G2 Spirit BioTwin 120 kV Cryo-TEM. Images were captured at 17,500x, 25,000x and 28,500x magnification.

Periodic disturbance mixer fabrication

The periodic disturbance mixer (PDM) microfluidic device was fabricated using soft lithography, as shown before54. In brief, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was degassed and poured onto SU-8 with the PDM design on it. The mold was kindly provided by Dr. Anas Alazzam from Khalifa University. After a second degas step, the PDMS was cured at 65 °C for 4 h. Then the PDMS was peeled off and inlets and outlets pierced with a biopunch. Finally, the PDMS element was bonded to a microscope slide (Globe Scientific Inc., Mahwah, NJ), after treating both the PDMS and the glass with oxygen plasma (Glow Research, Tempe, AZ). Tygon tubing and PEEK tubing were used to connect the device ports to syringes.

Liposome production and characterization

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), cholesterol (CHOL), dihexadecyl phosphate (DHP), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), 2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOTAP) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) was purchased from Echelon Biosciences (Salt Lake City, UT, USA).

Ethanol 96%, EMPROVE® EXPERT, Pur-A-Lyzer™ dialysis units and Syringe filters Millex-LG 0.20 μm were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St-Louis, MO, USA). Masterflex tubes and the Ultrasonic Cleaner were purchased from Cole-Parmer (Antylia Scientific, Vermont Hills, IL, USA). 10mL syringes with Luer-Lok®Tip were bought from BD (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Syringe pumps 11 Elite and Pico Elite were bought from Harvard Apparatus Canada (Saint-Laurent, QC, Canada) and EcoTherm HS40 hot plate was bought from Torreyy Pines (Carlsbad, CA, USA). SP-DiIC183 purchased from Invitrogen™ (Waltham, MA, USA) was used to dye the liposomes.

Liposomes were produced as follows. For anionic liposomes, the lipid mixture used was DMPC 50% molar ratio, CHOL 40–50% molar ratio and DHP 0–10% molar ratio. The DHP% was progressively increased at the expense of CHOL to evaluate its effect on the zeta potential and the size. A total of six lipid formulations were explored, ranging from 0 to 10% molar ratio of DHP.

For cationic liposomes, the lipid mixture used was DSPC 25% molar ratio, DOPE 12.5% molar ratio, CHOL 37.5–57.5% and DOTAP 5–25%. The DOTAP% was progressively increased at the expense of CHOL to evaluate its effect on the zeta potential and the size. A total of four lipid formulations were explored, ranging from 0 to 25% molar ratio of DOTAP.

Lipid concentration in the PDMS microfluidic chip was set at 10 mM, with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as the aqueous solvent. The flow rate ratio (FRR) was maintained at 1:1 between the lipid and aqueous phases, while the total flow rate (TFR) was 18 mL/h, controlled by the LipoSynthesis software as previously described55. The organic phase, consisting of lipid components mixed according to the established molar ratio, was prepared by sonication in ethanol at 45 °C for 15 min. Liposomes were collected at the outlet of the microfluidic chip, diluted in deionized water or Milli-Q® water to reach a final lipid concentration of 0.4 mM, and subjected to overnight dialysis against 4% PBS to achieve consistency in the solvent composition. Characterization of liposomes was performed using DLS, with three replicates per formulation to ensure measurement accuracy.

Design of experiment and surface response methodology

A design of experiment (DoE) approach using response surface modeling (RSM) was employed to build a quadratic model that predicts the size and surface charge of the liposomes. The three-factor circumscribed central composite rotatable (CCCR) design was created on Minitab® 19 to explore the effects of FRR, TFR and lipid percentage (DHP% for anionic and DOTAP% for cationic) on liposome Z-average and zeta potential.

Cellular uptake

Live cell imaging (Incucyte® S3) was used to assess the cellular uptake in real time, collecting five images per well with an interval of 2 h, for 24–48 h after treatment with liposomes. The cells were seeded in 96-well plates 24–48 h prior to the treatment with liposomes, with a density of 2500 cells per well. The red channel (excitation range 567–607 nm and emission range 622–704 nm) tracked the adherence and uptake of the dyed liposomes by IHH.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) (BD LSRFrotesa™) (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was used to quantitatively measured the cellular uptake. The cells’ nuclei were dyed using NucBlue™ from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). 100,000 to 300,000 IHH were seeded per well in 6-well plates and grown for 24 h prior to being exposed to 1e5-1e10 liposomes/cell (amount indicated in each experiment). After incubating for 24 h, the cells were fixed by detaching them and incubating them in paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature.

Confocal microscopy was also conducted to image liposome uptake by IHH. 10,000 cells were seeded in a 4-well Ibidi µ-Slide Poly-L-Lysine treated plates (Munich, Germany). Cells nuclei were dyed using NucBlue™, when required, cells lipid membrane were labeled with PKH67. Liposomes were labelled with dyes added in the lipid phase during the liposome synthesis in the microfluidic chip. Unbound free dyes were removed by dialysis performed overnight dialysis at 4 °C in 4% PBS. Cells were imaged LSM780 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), using an oil immersion objective (63x). The media was removed, and cells were fixed using paraformaldehyde 4%. The FlowJo™ Software was used to gate our samples, meaning that a specific region of the signal was selected for the analysis.

CCK8 assay

2500 cells were seeded per well in a 96-well plate. One day after, culture media was refreshed with liposomes added and cell confluence and liposome uptake were tracked by Incucyte® S3 over 24 h Then, 10 µL of CCK8 reagent (Dojindo Laboratories) was added to each well and incubated with the cells at 37 °C for 2 h. Absorbance at 450 nm was read by a plate reader (Tecan Infinite Pro 200). To account for the variation of differential cell growth over the two days since seeding, absorbance level was normalized to the last confluence scan by live cell imaging (Incucyte® S3).

Statistical tools

EV and liposome characteristics were assessed using ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The DoE and the RSM were produced using Minitab. It was assumed the variance is only dependent on the center point. The RSM used a quadratic model. The terms in the model were assessed using ANOVA to identify the goodness of fit and term significance. Only terms with p < 0.05 were kept.

Results

Heterogeneity of EVs in cancer lines

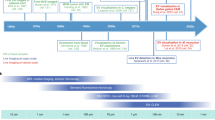

To build a synthetic model based on the characteristics of cancer EVs, we first sought to characterize the physicochemical properties of EVs derived from several cancer cell lines. To do this, we used a panel of well-characterized human cancer cell lines of distinct origins (PC-3, A-549, Hela, MP41, and OMM2.5; Table 1). A human fibroblast cell line (BJ) was used as non-cancer reference cell lines. Following the guidelines set by the 2018 International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV)56and Minimal Information for Studies on EVs (MISEV) 202357, EVs were isolated by ultracentrifugation and characterized as routinely performed in our laboratory35,58 (Fig. 2; Table 2). By NTA, the EV samples size ranged from 107.1 to 161 nm (Fig. 2A), and the calculated PDI from 0.13–0.27 (Fig. 2B). Details on the NTA parameters (script, camera level, temperature, and number of videos) is shown in Supplementary Table S1, and the NTA plots are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. DLS analysis revealed a size ranging from 152 to 355 nm (Supplementary Figure S2A) and a polydispersity index from 0.26 to 0.52 (Supplementary Figure S2B). Zeta potential was found to be −25 mV to −6 mV (Fig. 2C). The productivity (EVs/cell/h) isolated from culture media varied between cell lines from 0.02 to 7.01 EVs per cell per hour (Fig. 2D). Western blot was also performed to confirm the expression of EV markers (CD81, Syntenin and TSG101; Fig. 2E) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to visualize the EVs (Fig. 2F). As expected, we see a larger average size when measured by DLS as compared to NTA, as previously described59. In our experience, DLS measurement of size is highly dependent on concentration of particles, with a higher Z-average result from more diluted samples, such as EVs (Supplementary Figure S3).

Cell-derived extracellular vesicles were characterized from a panel of cancer and non-cancer cell lines. (A) Average EV diameter (nm) was assessed by NTA. (B) PDI was calculated from NTA as (Standard Deviation)2 / (Mean Particle Size)2. (C) Zeta potential was calculated by electrophoretic mobility and (D) EV/cell/h productivity by NTA. (E) Western blot was performed for common EV markers CD81, syntenin and TSG101. (F) TEM was used to visualize the EVs (concentrations provided for each sample as particles/mL). Table 2 shows the corresponding detailed description of the obtained values. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

EV-mimicking anionic liposome production using the PDM for reproducible and high throughput production

We utilized a periodic disturbance micromixer (PDM) microfluidic chip to produce bioinspired liposomes in a range of size and zeta potential like the characterized EVs (Fig. 3). This method resulted in liposome formulations within the range of 90–222 nm with zeta potential ranging from anionic (−47 mV) to neutral (−1 mV), at a production throughput of up to 41 mL/h and yielding a concentration of 1 × 1012 particles per mL. This translated to 1000x more concentrated liposomes as their natural occurring counterparts. The curvilinear paths in the PDM microchannels enable the creation of Dean vortices that rapidly mix the aqueous and the organic solvent in milliseconds in a uniform way (laminar flow) allowing reproducible and control-sized liposomes.

Zeta potential modulation

Several parameters, such as lipid composition, affect the Z-average and zeta potential of liposomes60,61. Here, we sought to determine the experimental parameters that affect zeta potential in anionic liposomes. As expected, the zeta potential highly depends on the formulation of liposomes. For anionic liposomes, the DHP% was used as a factor in our experimental approach. Initial formulation was DMPC: CHOL 1:1, (DMPC% remained constant while CHOL% is reduced to accommodate the DHP%). With the goal to modulate the physicochemical parameters of liposomes with DHP%, the DHP molar ratio progressively increased, at the expense of the CHOL ratio%, which decreased from 50 to 40%. Changing the ratio of the negatively charge lipid DHP yielded a significant difference between the sample groups (p-value < 0.0001). Supplementary Figure S4A showcases the change of zeta potential as the DHP% increases. The percent of DHP had no impact on the Z-average and PDI (Supplementary Figure S4B).

Liposome modeling optimized by central circumscribed composite design (CCCR)

To mimic EV physiochemical properties, we created a statistical model that connected the production parameters or factors (lipid formulations and flow rates) with the final liposome properties (size, PDI and zeta potential). Our group has previously demonstrated the use of response surface modeling (RSM) using 2-factors to model size in a PDM62. PDM-based liposome production proved to be reproducible and yield monodispersed to low polydispersed populations. Inspired by our previous design of experiment approach62, here we expanded the model to include the zeta potential by adding the anionic lipid (DHP) at different concentrations at the expense of CHOL in the DMPC: CHOL mixture. As a result, we obtained a three-dimensional experimental space. Using RSM we were able to model zeta potential and Z-average (diameter) by controlling TFR, FRR and DHP%.

The three-factor central circumscribed composite design (CCCR) was used to optimize liposome preparation considering these three key parameters (Supplementary Figure S5). The experimental design included 6 axial points (red), 8 cubic points (blue), and 1 central point (yellow), each with at least 3 replicates to ensure the reliability of the results. The table (Supplementary Figure S5) shows the coded value, as well as the parameters for TFR (total flow rate), FRR (flow ratio), and DHP% (dihydrogen phosphate percentage). For example, the coded value 1.68, 0, 0 corresponds to FRR = 12, TFR = 27.50 mL/h, and DHP% = 5.

To optimize the design, 47 preparation cycles were performed (Supplementary Table S2), with each cubic and axial point repeated three times, and the central point repeated five times. A quadratic model was then applied to predict liposome diameter and zeta potential, discarding terms without sufficient statistical significance to improve model accuracy. The 47 samples were produced randomly according to the Minitab® DoE.

This rotatable surface response model, particularly the CCCR, yielded a quadratic equation for each response and identified the significant factors influencing the size and surface charge of the liposomes. The R2 predicted accounts for the future responses: 79.77% for the zeta potential and 65.20% for the Z-average (Fig. 4A and B). The analysis of variance identified the FRR and DHP% as influential factors for the zeta potential and TFR and FRR were significant for Z-average. The lipid composition (DHP%) did not affect the size (p-value = 0.516) and the TFR did not affect the zeta potential (p-value = 0.972). These results are congruent with past studies62. The quadratic equations obtained for each response are shown below:

Contour plots responses for diameter and zeta potential for anionic liposomes.(A) Diameter response before dialysis in function of FRR and TFR. (B) Zeta potential in function of FRR and DHP% before dialysis. (C) Diameter response after dialysis in function of FRR and TFR (D) Zeta potential in function of FRR and DHP% after dialysis. (E) Response and R-squared value for the conditions before dialysis and after dialysis.

\(zeta \, potential\:=\:-27.60+6.54\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}-6.89\text{D}\text{H}\text{P}-0.36{\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}}^{2}+0.25{\text{D}\text{H}\text{P}}^{2}\)

\(Z-average\:=\:270.5-24.92\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}-1.206\text{T}\text{F}\text{R}+2.332{\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}}^{2}\)

Optimization of model by adding dialysis

The changes in FRR produce a difference in the concentration of ions in the final sample which alters the surface charge of the liposomes (Supplementary Table S2). The zeta potential measures the surface charge of the liposomes at the slipping plane which is highly affected by the ionic strength of the solvent63. To address this, the samples were dialyzed against 4% PBS to standardize the concentration of ions. After characterization by DLS, a new model was obtained (Fig. 4C, D and E and Supplementary Figure S6). Dialysis significantly affects physicochemical properties of anionic liposomes (Supplementary Table S3 and S4).

The dialysis step improved the R2 predicted for the zeta potential (86.71%) but not for the Z-average (64.31%). The factors influencing both responses remained the same:

\(Dialyzed \,zeta\, potential \:=3.20-0.695*FRR-8.523*DHP+0.4338*{DHP}^{2}\)

\(Z-average \:=240.5-21.34*FRR-1.034*TFR+1.164\:{FRR}^{2}\)

Targeted vs. actual liposome parameters mimicking EVs

The statistical model enabled us to get the factors (production parameters) required to manufacture bioinspired liposomes with size and zeta potential in the range of EVs. In Table 3, we show the different formulations examples and the targeted values, as well as the margin of error for them. We achieved a size error that is on average 4.85 nm with a standard deviation of 10.34 nm. On the other hand, for the zeta potential, we had an average error of 4.9 mV with a standard deviation of 3.5 mV. The results are in accordance with the R-square predicted from the previous section.

The zeta potential of the resulting liposomes was controlled by changing the concentration of DHP% following the previously described model. The zeta potential of the resulting nanoparticles was set to go from neutral to anionic. The range was established based on the assumption, to the knowledge of the authors, that the existence of cationic natural occurring EVs has not been proved42.

Model expanded for cationic liposomes

While EVs have a negative zeta potential due to their surface moieties42, further exploration of the experimental space was made, and a three-factor RSM, specifically the same CCCR approach, on cationic liposomes was built. Cationic liposomes, although different from natural EVs, play a crucial role in the delivery of nucleic acids for gene therapy and drug delivery. Their importance lies in several key features: (i) Their ability to form stable complexes with negatively charged nucleic acids, ensuring their protection against degradation. (ii) Their positive charge that promotes interaction with cell membranes, thus improving cellular uptake and transfection efficiency. (iii) The possibility of adjusting their lipid composition to optimize their physicochemical properties and delivery efficiency64. (iv) The ability of some cationic liposomes, especially those containing fusogenic lipids such as DOPE, to facilitate endosomal escape65. These features make cationic liposomes particularly interesting for various therapeutic applications, from mRNA-based vaccination to anticancer drug delivery. Although they are not natural EVs, the study of cationic liposomes can provide valuable insights into intracellular delivery mechanisms and inspire the development of hybrid delivery systems combining the advantages of synthetic liposomes and natural EVs.

In this context, four lipids, DSPC, DOPE, DOTAP and CHOL were used in the synthesis of liposomes. The formulation used to build the cationic response surface model was DSPC: CHOL: DOPE: DOTAP in molar ratios ranging from 5 to 25% DOTAP and 57.5–37.5% CHOL, and constant DOPE (12.5%) and DSPC (25%).

The positively charged lipid DOTAP is utilized to modulate the zeta potential of the cationic liposomes since the effect of DOTAP and the zeta potential has been widely studied in the past53,61. As shown in Supplementary Figure S7A, DOTAP% significantly impacted zeta potential. In contrast, the z-average was not impacted by DOTAP%, although interestingly, the PDI was impacted (Supplementary Figure S7B).

As for anionic liposomes, 47 preparation cycles were performed to optimize the design for cationic lipids (Supplementary Table S5), with each cubic and axial point repeated three times, and the central point repeated five times.

Using the same methodology (CCCR), the control parameters were FRR, TFR and percentage of the charged lipid DOTAP%. The R2 predicted accounts for the future responses: 78.90% for the zeta potential and 10.64% for the Z-average (Fig. 5A and B). The three-factor cationic model quadratic equations obtained for each response are shown below.

Contour plots responses for diameter and zeta potential for cationic liposomes. (A) Diameter response before dialysis in function of FRR and TFR after dialysis. (B) Zeta potential in function of FRR and DOTAP% before dialysis. (C) After dialysis. (D) Response and R-squared value for the conditions before dialysis and after dialysis.

\(zeta\,potential \:=\:15.81-1.505\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}+2.698\text{D}\text{O}\text{T}\text{A}\text{P}-0.0625{\text{D}\text{O}\text{T}\text{A}\text{P}}^{2}\)

\(Z-average\:=\:278.5-46.9\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}+3.016{\text{F}\text{R}\text{R}}^{2}\)

As with anionic liposomes, the samples were dialyzed against 4% PBS to standardize the concentration of ions. Dialysis significantly affects physicochemical properties of cationic liposomes (Supplementary Table S3 and S6). After characterization by DLS, a new model was obtained (Fig. 5C and D and Supplementary Figure S8). The dialysis step improved the R2 predicted for the Z-average (36.53%) but not for the zeta potential (54.77%). The three-factor cationic model quadratic equations after dialysis are shown below.

\(Dialyzed\,zeta\,potential\:=11.78-05FRR+2.9DOTAP-0.1FR{R}^{2}-{0.1DOTAP}^{2}\)

\(Dialyzed\,Z-average\:=415.8-474FRR-1.1TFR-8.7DOTAP+2.1FR{R}^{2}+FRR*DOTAP\)

Dialysis revealed that all three factors (DOTAP, FRR and TFR) are significant factors for the size response. The R-squared obtained for this cationic model without and with dialysis is given in Fig. 5.

Assessment of EV-like liposome internalization by human cells

We previously demonstrated the uptake of cancer cell EVs by human cells in vitro within 6 h35. Here to demonstrate the uptake of cancer cell-derived EVs over time, we used live cell imaging to monitor uptake of SP-DiIC183 (red) labelled EVs isolated from MP41 cells. We used immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) as recipient cells because these cells are important components of the liver microenvironment, the most common site of metastasis by solid tumors. Indeed, we validated that EVs are internalized by IHH cells over 44 h of tracking (Fig. 7).

Cellular uptake of EVs is shown over 44 h. (A) IHHs were treated with MP41 cell-derived EVs at a concentration of ~ 105 EVs per cell and visualized by live cell imaging (Incucyte) over 44 h. Control indicates a buffer-only control stained and purified in the same method as MP41 EVs. (B) Images were captured at 12, 24 and 44 h. EVs were labeled with SP-DiIC183 (red).

Next, we wanted to demonstrate that liposomes can be uptaken by the same recipient cells in a similar timeframe. To assess uptake, EV-like liposomes (149 nm, −12mV) were labelled using SP-DiIC183 (red) dye and incubated with IHH (labeled in green). To identify the adequate concentration of liposomes to evaluate the cellular uptake, fluorescent imaging and Incucyte were used to evaluate the cellular uptake by recipient cells (IHH). To identify the optimal time frame, liposome and cell concentration, we performed a time course analysis by fixing cells at different time points (0, 3, 6 and 12 h). While a few puncta are observed after 3 h, labeled liposomes were consistently present in anionic liposomes after 6 h, as shown in Fig. 7 for a concentration of 107 liposomes per cell.

Cellular uptake of anionic liposomes is shown over 12 h. IHHs were treated with 107liposomes per cell and visualized by confocal microscopy at the indicated time points. IHH membranes were labeled with PKH67 (green), while the nuclei were labeled win NucBlue™ (blue). Liposomes (149 nm, −12mV) were labeled with SP-DiIC183 (red).

To determine the effect of charge on uptake, we also compared the uptake on IHH using anionic, neutral and cationic liposomes. Using a concentration of 105 liposomes per cell, we can see significantly more uptake by smaller, more positively charged liposomes, as expected (Fig. 8A, B).

Cellular uptake of liposomes is shown over 24 h. (A) IHHs were treated with 105 liposomes per cell and visualized by live cell imaging on Incucyte. IHH membranes were labeled with PKH67 (green), while the nuclei were labeled win NucBlue™ (blue). Liposomes are labeled with SP-DiIC183 (red). (B) Red fluorescence of liposomes (2.5e13/mL), represented as red fluorescence area (µm2), of one cationic (56 nm and + 41mV) and 2 anionic liposomes (Anionic 1 = 89 nm and − 26mV; Anionic 2 = 157 nm and − 26mV) over 24 h of treatment on IHH. Data was shown as mean of quadruplicated wells +/-SD. Representative images of cellular uptake of corresponding liposomes at 24 h. Scale bar = 400 μm. (C) Cellular metabolic activity post 24 h of liposomes uptakeusing a the CCK8 assay for cells treated at 109 liposomes/cell. Data was shown as mean of the absorbance (450 nm) normalized to confluence (%) of quadruplicated wells +/-SD. **: p< 0.01.

Cationic liposomes have been previously demonstrated to induce cell toxicity66,67. A CCK8 assay was used to assess the metabolic activity of the recipient cells to determine toxicity. Metabolic analysis at different concentrations showed anionic liposomes did not have a major effect on IHH metabolic activity, however, cationic liposomes did affect the metabolic rate of CCK at high concentrations (109 liposomes per cell) Fig. 8C).

Size and zeta potential impact uptake of individual and combination of liposome populations

To exert their effect, EVs must first be internalized by recipient cells, where they can then transfer cargo and modulate cellular behavior35,36,39. While EV size and zeta potential are important factors when characterizing EVs42,43 their role in cellular uptake has not been fully identified. Therefore, we next sought to determine the effect of size and zeta potential in uptake using our synthetic model. IHHs were incubated with liposomes of different sizes and zeta potentials that reproduce the physicochemical parameters of naturally occurring EV.

To investigate the influence of zeta potential, four different formulations were prepared. The zeta potential of the resulting liposomes was controlled by changing the concentration of DHP following the previously described model, while maintaining a similar size. As expected, there was an increase in uptake by both IHH with increasing zeta potential (less negative) as shown by flow cytometry (Fig. 9A and B). Among liposomes of a particular zeta potential (~ −25mV), smaller liposomes (~ 90 nm) showed a higher uptake by IHHs, shown by flow cytometry (Fig. 9C and D). This sheds light on the role of size of the nanoparticle when interacting with the cellular surface: liposomes sharing a similar composition and surface charge but differing in size will show a different uptake by cells.

Effect of size and zeta potential on uptake in individual and combination liposome populations. Flow cytometry was used to measure fluorescently labeled liposomes with A) different zeta potentials (similar size), quantified in B, and with C) different sizes (similar zeta potential), quantified in D, on immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) at 24 h after liposome treatment. E) Microscopy images showing IHH uptaking different populations of liposomes with different sizes, zeta potentials, and fluorescent label as shown in the Table. Representative images at 24 h post liposome treatment. Liposome modelling EV subpopulations. Cells were treated with 107 liposomes/cell. Liposome membrane incorporated with 14:0 Liss Rhod PE (red) or 14:0 NBD PE (green). Blue: Hoechst stain for cell nucleus.

EVs are known for their high heterogeneity. Indeed, there is growing research on EV subpopulations in terms of different sizes21,22, lipid profiles19,20, and surface markers68,69. While our liposomes are homogenous–in contrast to heterogenous EV populations–the goal of studying individual EV components requires a homogenous system so that other parameters are controlled. However, to demonstrate that our model can be adapted to study combinational effects seen in heterogenous EV populations, we created different EV-like liposome formulations that modeled different EV subpopulations and labeled each with a different fluorescent tag Fig. 9E). Indeed, when added on IHHs, we saw differential uptake by the same cells, with smaller EVs being uptaken preferentially by most cells, as demonstrated here Fig. 9C and D) and previously70.

Discussion

EVs are key mediators of cell-cell communication and have been shown to play a role in tumor progression and metastasis. This heterogeneity of EVs, both in terms of size, composition and function, represents a major challenge for understanding their precise role in tumor progression. This, along with lengthy isolation procedures with low yield, make it difficult to study the unique characteristics of EVs that may be contributing to their function in physiological conditions and in pathologies like cancer. To overcome these obstacles, synthetic vesicles (SVs), which are EV-mimetics synthesized de novo from molecular components or made as hybrid entities57, have emerged as a promising area of research71,72,73. These SVs can be categorized based on their synthesis methods – “top down”, shearing of cells into nanoparticles; “bottom up”, synthesis of bioinspired liposomes by mixing individual biomolecules; and “hybrid”, fusion of EVs and liposomes. Reviewed by Li et al., EV mimetic vesicles have a mean size ranging from 80 to 1000 nm and a negative zeta potential, with DLS and NTA being the most used techniques for particle characterization73. Notably, EV mimetics have been shown to enhance particle yield by over one hundred times, compared to EV isolates74,75,76. EV mimetic SVs leveraged the strengths of EVs and liposomes, exhibiting high biocompatibility, customizability, and scalability. They hold high potential for a variety of biomedical applications, such as tumor targeting, gene delivery, and regenerative medicine71,72,73.

In this work, we sought to develop a novel synthetic model to mimic cancer EVs, which could be used to study the effects of individual and combinations of EV characteristics on cellular uptake. This represents a new application of EV mimetics, with the goal of uncovering the role of EVs in cancer processes. This innovative approach aims to overcome the limitations inherent in the study of natural EVs, including their low yield and heterogeneity. To meet this goal, we first sought to have a comprehensive understanding of the physicochemical properties of naturally derived EVs. We analyzed an array of EVs derived from different cell lines by multiple techniques, including TEM, DLS, Nanosight, and Zetaview. Our analysis revealed technique-dependent variations in measurements. Particularly, we noticed a significant discrepancy in size characterization, with DLS reporting much larger sizes (152 to 355 nm) compared to Nanosight (107.1–161 nm). We observed that DLS measurement of size is highly dependent on the concentration of the nanoparticles, with a higher Z-average resulted from more diluted samples, suggesting that it may not be suitable for the characterization of low concentrated samples like EVs. Further validation with TEM, Nanosight, and Zetaview indicated a consensus of size between 100 and 200 nm for isolated small EVs. This in-depth characterization allowed us to establish a solid baseline for the design of our biomimetic liposomes. We then created EV-like liposomes by reproducing size and zeta potential and assessed their internalization by recipient cells. We successfully modeled EV size using liposomes within the range of 90–222 nm with zeta potential ranging from anionic (−47 mV) to neutral (−1 mV). We then also applied the same methodology to synthesize cationic liposomes, as these are important in the field of drug delivery, demonstrating the versality of our approach for other biomedical applications.

We produced liposomes using a bottom-up approach using a periodic disturbance micromixer, as previously demonstrated by our group55,62,77,78. Furthermore, our rational design approach, based on a DoE and an RSM, represents a significant advance in the production of synthetic vesicles mimicking EVs. Specifically, our mathematical modeling approach relies on a DoE and a RSM. This methodology allowed us to systematically optimize the lipid composition and production conditions to obtain liposomes with the desired properties. We showed that we can effectively reproduce size and zeta potential by modulating flow conditions and lipid formulation. The EV-like liposomes produced in this work have concentrations at least 1000 higher than naturally occurring EVs and they are produced in minutes compared to days for natural EVs. Second, our approach allows precise control of physicochemical properties, which is crucial to study the impact of specific parameters on cellular uptake. Moreover, we overcome technical challenges associated with studying natural occurring EVs that enables us to study one variable at a time which is not possible with heterogenous populations. The developed methodology will allow us to progressively mimic specific EV parameters that will allow us to both create bioinspired therapeutics and study cancer biology mechanisms with selective tools.

The selection of phospholipids for our liposomal formulations is based on established biophysical and functional considerations. DMPC DOPE and DOPS are synthetic lipids that we used as analogs of major lipid classes found in typical EV lipid compositions. DMPC is a synthetic analog of naturally occurring phosphatidylcholine (PC), which is one of the most abundant lipid classes in EVs. While EVs naturally contain PC with varying acyl chain lengths (e.g., POPC, DPPC), synthetic versions like DMPC are often used in liposome and LNP formulations due to their well-defined properties and stability. DMPC and DSPC were chosen for their distinct transition temperatures (Tm) (24 °C and 55 °C, respectively)79,80, and as phospholipids, they represent the major lipid family found in EVs, making them ideal candidates for biomimetic formulations. The presence of cholesterol at high ratios (37.5–57.5%) is justified by its crucial role in membrane stiffening and structural stability of vesicles81,82,83. This stiffening is particularly important for DMPC liposomes that naturally exhibit increased fluidity at 37 °C. DOPE was incorporated into the cationic formulation for its fusogenic properties84that promote cellular internalization, while DHP and DOTAP allow to modulate negative and positive charges, respectively. These composition choices make it possible to obtain biomimetic liposomes with controlled physicochemical properties, particularly in terms of membrane rigidity and surface charge, two parameters that directly influence cellular internalization85. The progressive modulation of the DHP (0–10%) and DOTAP (5–25%) ratios to the detriment of cholesterol makes it possible to systematically study the impact of the charge on cellular uptake while maintaining sufficient structural stability.

While nanoparticle uptake is not entirely dictated by size and charge potential, we demonstrate that these parameters significantly impact cellular uptake. The zeta potential is described as the charge at the slipping which differs from the electric surface potential itself. Our model can therefore reproduce the zeta potential of natural EVs in terms of interaction with the physiological environment. This ability to faithfully reproduce the zeta potential is important, especially because the electrostatic interactions between cell membrane and nanoparticle have been shown to influence cellular uptake and biodistribution86, indicating that potential gradient is an important factor for the nanoparticle-cell interaction.

While our bottom-up synthesis of liposomes enables precise control over size, charge, and composition, it is acknowledged that top-down and hybrid approaches facilitate the production of biomimetic SVs with preserved membrane proteins, allowing for selective targeting and enhanced interactions with recipient cells. Various synthesis methods have been developed to generate biomimetic SVs, including extrusion, sonication, freeze-thaw cycles, and homogenization for cell-derived nanovesicles, as well as thin-film hydration and microfluidics for bottom-up synthesis73,87. Each approach presents distinct advantages and limitations, contributing to advancements in disease targeting, diagnostics, and fundamental research73,87. For instance, Balboni et al. (2024) demonstrated the potential of glioblastoma-derived cell membrane nanovesicles in boron neutron capture therapy, highlighting the advantages of maintaining cell-specific membrane properties88. Other groups have also produced EV-like SVs using different approaches71, providing new perspectives to overcome the limitations of natural EVs. Heng Chng et al. (2023) conducted a comparative study demonstrating that cell derived nanovesicles, produced by shearing cells through membrane filters, exhibit significant similarities to natural EVs in terms of size, proteomic and lipidomic composition, and miRNA profile89. This method increased the yield by at least 15-fold compared to natural EVs, thus offering a potential solution to the low yield problem often encountered with natural EVs. Other groups have explored “bottom-up” approaches to create synthetic EVs. For example, De La Pena et al. (2009) created artificial EVs by coating liposomes with MHC Class I/peptide complexes and a selected specific range of ligands to activate T cells90. Molinaro et al. (2018) produced liposomes loaded with leukocyte membrane proteins, which extended the circulation time of the biomimetic SVs, as well as achieved targeting of inflammation91. Finally, Sakai-Kato (2020) imitated EVs released from HepG2 (a liver cancer cell) by fabricating liposomes with a similar lipid composition, stiffness, and surface charge92. The liposomes were made using the thin film hydration method. They subsequently studied how HeLa cells were responding and absorbing these liposomes. Another interesting innovation is the development of hybrid vesicles. Zhou et al. (2021) created hybrid lipid nanovesicles (LEVs) by fusing EVs with liposomes93. This approach improved the transfection efficiency of siRNAs up to seven-fold, opening new possibilities for gene therapy. Surface modification of EVs is another strategy that has gained importance. Lim et al. (2022) used glycometabolic engineering to modify the surface of EVs with azide moieties, allowing specific targeting of CD44-overexpressing tissues94. This approach offers new possibilities for precise targeting of EV-based therapies.

In this dynamic research context, our work stands out and contributes significantly to the field by developing a mathematical model to optimize the production of biomimetic liposomes. This approach offers several unique advantages1: Precise control: our model allows fine tuning of physicochemical properties, including size and zeta potential, which is not easily achievable with other methods2. Reproducibility: the use of a DoE and response surface model ensures high reproducibility in the production of biomimetic liposomes3. Efficiency: our method produces liposome concentrations significantly higher than those of natural EVs, in just a few minutes4. Versatility: the model can be adapted to mimic different types of EVs, providing a flexible platform for various applications in cancer research and therapeutics, and5 Mechanistic study: our approach allows for studying the impact of specific parameters on cellular uptake, which is not possible with heterogeneous populations of natural EVs. Thus, by combining these advantages, our work opens new perspectives for the understanding of intercellular communication mechanisms in cancer and the development of targeted EV-based therapies. It fills an important gap between studies on natural EVs and the development of highly controlled biomimetic drug delivery systems.

Finally, it is important to note that our approach is distinct from commercial fabrication for EV-based therapeutics exists, such as by Codiak, where EVs are produced in bioreactors and modified using scaffold proteins on an industrial scale95. Their approach is suitable for drug delivery and therapeutics but less so for the purpose of studying natural EV properties. Similarly, lipid-based nanoparticles, such as liposomes, have been widely studied as a drug delivery system for therapeutics96. However, their potential as a tool to study natural EV biology is not well recognized. Our work fills this gap by demonstrating the value of biomimetic liposomes not only as potential drug delivery vehicles, but also as models to elucidate fundamental mechanisms of EV-mediated intercellular communication in the context of cancer.

However, while our model offers many advantages, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. For example, it does not yet reproduce the full complexity of natural EVs, particularly in terms of lipid, protein and RNA content. The next steps in our research will aim to incorporate these more complex components to further improve the fidelity of our biomimetic liposomes. Ongoing efforts to conduct comprehensive lipidomic and proteomic analyses, for example, will help to us to better mimic the composition of EVs for both biological discovery and as potential EV-based therapeutics.

Conclusion

Our study presents a novel approach to model cancer EVs using biomimetic liposomes. This method overcomes the limitations inherent in the study of natural EVs, including their heterogeneity and low yield. By accurately reproducing the size and zeta potential of EVs, we demonstrated that these parameters play a crucial role in cellular uptake, even in the absence of a complex protein corona. Our model opens new perspectives for the study of intercellular communication mechanisms in cancer and the development of targeted therapies. Future research can build on this foundation to integrate additional biological components, such as EV lipid and proteins, refining our understanding of the complex interactions between EVs and recipient cells. This promising approach could revolutionize our understanding of cancer biology and pave the way for new therapeutic strategies.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- EVs:

-

Extracellular vesicles

- FAVS:

-

Fluorescence-activated vesicle sorting

- TFF:

-

Tangential flow filtration

- DoE:

-

Design of experiment

- RSM:

-

Response surface methodology

- IHH:

-

Immortalized human hepatocytes

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- PDI:

-

Polydispersity index

- NTA:

-

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

- PVDF:

-

Polyvinylidene fluoride

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

- PDM:

-

Periodic disturbance mixer

- PDMS:

-

Polydimethylsiloxane

- CHOL:

-

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), cholesterol

- DHP:

-

Dihexadecyl phosphate

- DSPC:

-

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOTAP:

-

2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOPE:

-

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- FRR:

-

Flow rate ratio

- TFR:

-

Total flow rate

- CCCR:

-

Circumscribed central composite rotatable

- ANOVA:

-

One-way analysis of variance

- ISEV:

-

International Society for Extracellular Vesicles

- MISEV:

-

Minimal Information for Studies on EVs

- SVs:

-

Synthetic vesicles

- PC:

-

Phosphatidylcholine

- CDNs:

-

Cell-derived nanovesicles

- LEVs:

-

Hybrid lipid nanovesicles

- RBCEVs:

-

Red blood cell-derived vesicles

References

Abels, E. R. & Breakefield, X. O. Introduction to extracellular vesicles: biogenesis, RNA cargo selection, content, release, and uptake. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 36 (3), 301–312 (2016).

Jeppesen, D. K. et al. Reassessment Exosome Composition Cell. ;177(2):428–45e18. (2019).

Kahlert, C. et al. Identification of Double-stranded genomic DNA spanning all chromosomes with mutated KRAS and p53 DNA in the serum exosomes of patients with pancreatic Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 289 (7), 3869–3875 (2014).

Thakur, B. K. et al. Double-stranded DNA in exosomes: a novel biomarker in cancer detection. Cell. Res. 24 (6), 766–769 (2014).

Lee, T. H. et al. Barriers to horizontal cell transformation by extracellular vesicles containing oncogenic H-ras. Oncotarget 7 (32), 51991–52002 (2016).

Bellingham, S. A., Coleman, B. M. & Hill, A. F. Small RNA deep sequencing reveals a distinct MiRNA signature released in exosomes from prion-infected neuronal cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (21), 10937–10949 (2012).

Tsering, T. et al. EV-ADD, a database for EV-associated DNA in human liquid biopsy samples. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 11 (10), e12270 (2022).

Tsering, T., Nadeau, A., Wu, T., Dickinson, K. & Burnier, J. V. Extracellular vesicle-associated DNA: ten years since its discovery in human blood. Cell. Death Dis. 15 (9), 668 (2024).

Liang, B. et al. Characterization and proteomic analysis of ovarian cancer-derived exosomes. J. Proteom. 80, 171–182 (2013).

Thery, C. et al. Proteomic analysis of dendritic cell-derived exosomes: a secreted subcellular compartment distinct from apoptotic vesicles. J. Immunol. 166 (12), 7309–7318 (2001).

Tauro, B. J. et al. Two distinct populations of exosomes are released from LIM1863 colon carcinoma cell-derived organoids. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 12 (3), 587–598 (2013).

Zaborowski, M. P., Balaj, L., Breakefield, X. O. & Lai, C. P. Extracellular vesicles: composition, biological relevance, and methods of study. Bioscience 65 (8), 783–797 (2015).

Spinelli, C., Adnani, L., Choi, D. & Rak, J. Extracellular vesicles as conduits of Non-Coding RNA emission and intercellular transfer in brain tumors. Noncoding RNA ;5(1). (2018).

Di Vizio, D. et al. Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am. J. Pathol. 181 (5), 1573–1584 (2012).

Cocucci, E. & Meldolesi, J. Ectosomes and exosomes: shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell. Biol. 25 (6), 364–372 (2015).

van Niel, G., D’Angelo, G. & Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (4), 213–228 (2018).

Boireau, W. & Elie-Caille, C. [Extracellular vesicles: definition, isolation and characterization]. Med. Sci. (Paris). 37 (12), 1092–1100 (2021).

Tian, Y. et al. Quality and efficiency assessment of six extracellular vesicle isolation methods by nano-flow cytometry. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 9 (1), 1697028 (2020).

Hussey, G. S. et al. Lipidomics and RNA sequencing reveal a novel subpopulation of nanovesicle within extracellular matrix biomaterials. Sci. Adv. 6 (12), eaay4361 (2020).

Elmallah, M. I. Y. et al. Lipidomic profiling of exosomes from colorectal cancer cells and patients reveals potential biomarkers. Mol. Oncol. (2022).

Lázaro-Ibáñez, E. et al. DNA analysis of low- and high-density fractions defines heterogeneous subpopulations of small extracellular vesicles based on their DNA cargo and topology. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 8 (1), 1656993 (2019).

Crescitelli, R. et al. Subpopulations of extracellular vesicles from human metastatic melanoma tissue identified by quantitative proteomics after optimized isolation. J. Extracell. Vesicles ;9(1). (2020).

Ciardiello, C., Leone, A. & Budillon, A. The crosstalk between Cancer stem cells and microenvironment is critical for solid tumor progression: the significant contribution of extracellular vesicles. Stem Cells Int. 2018, 6392198 (2018).

Desrochers, L. M., Antonyak, M. A. & Cerione, R. A. Extracellular vesicles: satellites of information transfer in Cancer and stem cell biology. Dev. Cell. 37 (4), 301–309 (2016).

Vader, P., Breakefield, X. O. & Wood, M. J. Extracellular vesicles: emerging targets for cancer therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 20 (7), 385–393 (2014).

Becker, A. et al. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: Cell-to-Cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell. 30 (6), 836–848 (2016).

Peinado, H. et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 18 (6), 883–891 (2012).

Skog, J. et al. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell. Biol. 10 (12), 1470–1476 (2008).

Al-Nedawi, K. et al. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat. Cell. Biol. 10 (5), 619–624 (2008).

Keller, S. et al. Systemic presence and tumor-growth promoting effect of ovarian carcinoma released exosomes. Cancer Lett. 278 (1), 73–81 (2009).

Ramteke, A. et al. Exosomes secreted under hypoxia enhance invasiveness and stemness of prostate cancer cells by targeting adherens junction molecules. Mol. Carcinog. 54 (7), 554–565 (2015).

Hsu, Y. L. et al. Hypoxic Lung-Cancer-Derived extracellular vesicle MicroRNA-103a increases the oncogenic effects of macrophages by targeting PTEN. Mol. Ther. 26 (2), 568–581 (2018).

Baroni, S. et al. Exosome-mediated delivery of miR-9 induces cancer-associated fibroblast-like properties in human breast fibroblasts. Cell. Death Dis. 7 (7), e2312 (2016).

Su, M. J., Aldawsari, H. & Amiji, M. Pancreatic Cancer cell Exosome-Mediated macrophage reprogramming and the role of MicroRNAs 155 and 125b2 transfection using nanoparticle delivery systems. Sci. Rep. 6, 30110 (2016).

Tsering, T. et al. Uveal Melanoma-Derived extracellular vesicles display transforming potential and carry protein cargo involved in metastatic niche Preparation. Cancers (Basel) ;12(10). (2020).

Abdouh, M. et al. Oncosuppressor-Mutated cells as a liquid biopsy test for Cancer-Screening. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 2384 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. Genetically engineered extracellular vesicles harboring transmembrane scaffolds exhibit differences in their size, expression levels of specific surface markers and Cell-Uptake. Pharmaceutics 14 (12), 2564 (2022).

De Jong, O. G. et al. Drug delivery with extracellular vesicles: from imagination to innovation. Acc. Chem. Res. 52 (7), 1761–1770 (2019).

Abdouh, M. et al. Colorectal cancer-derived extracellular vesicles induce transformation of fibroblasts into colon carcinoma cells. J. Experimental Clin. Cancer Res. 38 (1), 257 (2019).

Mulcahy, L. A., Pink, R. C. & Carter, D. R. F. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 3 (1), 24641 (2014).

Mathieu, M., Martin-Jaular, L., Lavieu, G. & Théry, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell Biol. 21 (1), 9–17 (2019).

Midekessa, G. et al. Zeta potential of extracellular vesicles: toward Understanding the attributes that determine colloidal stability. ACS Omega. 5 (27), 16701–16710 (2020).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Towards defining reference materials for measuring extracellular vesicle refractive index, epitope abundance, size and concentration. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 9 (1), 1816641 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat. Cell. Biol. 20 (3), 332–343 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Leveraging nature’s nanocarriers: Translating insights from extracellular vesicles to biomimetic synthetic vesicles for biomedical applications. Sci. Adv. 11, eads5249. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ads5249 (2025).

Leung, A. W. Y., Amador, C., Wang, L. C., Mody, U. V. & Bally, M. B. What drives innovation: the Canadian touch on liposomal therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 11 (3), 26 (2019).

Jahn, A., Vreeland, W. N., Gaitan, M. & Locascio, L. E. Controlled vesicle Self-Assembly in microfluidic channels with hydrodynamic focusing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (9), 2674–2675 (2004).

Zhigaltsev, I. V. et al. Bottom-Up design and synthesis of limit size lipid nanoparticle systems with aqueous and triglyceride cores using millisecond microfluidic mixing. Langmuir 28 (7), 3633–3640 (2012).

Belliveau, N. M. et al. Microfluidic synthesis of highly potent Limit-size lipid nanoparticles for in vivo delivery of SiRNA. Mol. Therapy Nucleic Acids. 1 (8), e37 (2012).

Hood, R. R., Vreeland, W. N. & DeVoe, D. L. Microfluidic remote loading for rapid single-step liposomal drug Preparation. Lab. Chip. 14 (17), 3359–3367 (2014).

Webb, C. et al. Using microfluidics for scalable manufacturing of nanomedicines from bench to GMP: A case study using protein-loaded liposomes. Int. J. Pharm. 582, 119266 (2020).

Lopez, R. R. et al. Parametric study of the factors influencing liposome physicochemical characteristics in a periodic disturbance mixer. Langmuir 37 (28), 8544–8556 (2021).

Smith, M. C., Crist, R. M., Clogston, J. D. & McNeil, S. E. Zeta potential: a case study of cationic, anionic, and neutral liposomes. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409 (24), 5779–5787 (2017).

López, R. R. et al. Parametric Study of the Factors Influencing Liposome Physicochemical Characteristics in a Periodic Disturbance Mixer. Langmuir. (2021).

López, R. R. et al. C, et al. The Effect of Different Organic Solvents in Liposome Properties Produced in a Periodic Disturbance Mixer: Transcutol®, a potential organic solvent replacement. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces2020.

Thery, C. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 7 (1), 1535750 (2018).

Welsh, J. A. et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): from basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 13 (2), e12404 (2024).

Pessuti, C. L. et al. Characterization of extracellular vesicles isolated from different liquid biopsies of uveal melanoma patients. J. Circ. Biomark. 11, 36–47 (2022).

Filipe, V., Hawe, A. & Jiskoot, W. Critical evaluation of nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) by nanosight for the measurement of nanoparticles and protein aggregates. Pharm. Res. 27 (5), 796–810 (2010).

van der Koog, L., Gandek, T. B. & Nagelkerke, A. Liposomes and extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems: A comparison of composition, pharmacokinetics, and functionalization. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 11 (5), e2100639 (2022).

Soema, P. C., Willems, G-J., Jiskoot, W., Amorij, J-P. & Kersten, G. F. Predicting the influence of liposomal lipid composition on liposome size, zeta potential and liposome-induced dendritic cell maturation using a design of experiments approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 94, 427–435 (2015).

López, R. R. et al. Surface response based modeling of liposome characteristics in a periodic disturbance mixer. Micromachines 11 (3), 235 (2020).

Forest, V. & Pourchez, J. Preferential binding of positive nanoparticles on cell membranes is due to electrostatic interactions: A too simplistic explanation that does not take into account the nanoparticle protein Corona. Mater. Sci. Engineering: C. 70, 889–896 (2017).

Dey, A. K. et al. Tuning the immunostimulation properties of cationic lipid nanocarriers for nucleic acid delivery. Front. Immunol. 12, 722411 (2021).

Ewert, K. K. et al. Cationic liposomes as vectors for nucleic acid and hydrophobic drug therapeutics. Pharmaceutics ;13(9). (2021).

Cui, S. et al. Correlation of the cytotoxic effects of cationic lipids with their headgroups. Toxicol. Res. (Camb). 7 (3), 473–479 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Cationic liposomes induce cytotoxicity in HepG2 via regulation of lipid metabolism based on whole-transcriptome sequencing analysis. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 19 (1), 43 (2018).

Komarova, E. Y. et al. Hsp70-containing extracellular vesicles are capable of activating of adaptive immunity in models of mouse melanoma and colon carcinoma. Sci. Rep. ;11(1). (2021).

Zhang, D. X. et al. αvβ1 integrin is enriched in extracellular vesicles of metastatic breast cancer cells: A mechanism mediated by galectin-3. J. Extracell. Vesicles ;11(8). (2022).

Choi, D. et al. Mapping subpopulations of Cancer Cell-Derived extracellular vesicles and particles by Nano-Flow cytometry. ACS Nano. 13 (9), 10499–10511 (2019).

Rosso, G. & Cauda, V. Biomimicking extracellular vesicles with fully artificial ones: A rational design of EV-BIOMIMETICS toward effective theranostic tools in nanomedicine. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 9 (11), 5924–5932 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Programming assembly of biomimetic exosomes: an emerging theranostic nanomedicine platform. Mater. Today Bio. 22, 100760 (2023).

Li, Y. J. et al. Artificial exosomes for translational nanomedicine. J. Nanobiotechnol. 19 (1), 242 (2021).

Wu, J. Y. et al. Exosome-Mimetic nanovesicles from hepatocytes promote hepatocyte proliferation in vitro and liver regeneration in vivo. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 2471 (2018).

Goh, W. J. et al. Bioinspired Cell-Derived nanovesicles versus exosomes as drug delivery systems: a Cost-Effective alternative. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 14322 (2017).

Jang, S. C. et al. Bioinspired exosome-mimetic nanovesicles for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutics to malignant tumors. ACS Nano. 7 (9), 7698–7710 (2013).

Lopez, R. R. et al. Numerical and experimental validation of mixing efficiency in periodic disturbance mixers. Micromachines (Basel) ;12(9). (2021).

López, R. R. et al. T, Parametric Study of the Factors Influencing Liposome Physicochemical Characteristics in a Periodic Disturbance Mixer. Langmuir. XX ed p. XX. (2020).

Lombardo, D. & Kiselev, M. A. Methods of liposomes preparation: formation and control factors of versatile nanocarriers for biomedical and nanomedicine application. Pharmaceutics ;14(3). (2022).

Liu, P., Chen, G. & Zhang, J. A review of liposomes as a drug delivery system: current status of approved products, regulatory environments, and future perspectives. Molecules ;27(4). (2022).

Doole, F. T., Kumarage, T., Ashkar, R. & Brown, M. F. Cholesterol stiffening of lipid membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 255 (4–5), 385–405 (2022).

Pohnl, M., Trollmann, M. F. W. & Bockmann, R. A. Nonuniversal impact of cholesterol on membranes mobility, curvature sensing and elasticity. Nat. Commun. 14 (1), 8038 (2023).

Nakhaei, P. et al. Liposomes: structure, biomedical applications, and stability parameters with emphasis on cholesterol. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 9, 705886 (2021).

Paliwal, S. R., Paliwal, R. & Vyas, S. P. A review of mechanistic insight and application of pH-sensitive liposomes in drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 22 (3), 231–242 (2015).

Amarandi, R. M., Ibanescu, A., Carasevici, E., Marin, L. & Dragoi, B. Liposomal-Based formulations: A path from basic research to Temozolomide delivery inside glioblastoma tissue. Pharmaceutics ;14(2). (2022).

Khadke, S., Roces, C. B., Cameron, A., Devitt, A. & Perrie, Y. Formulation and manufacturing of lymphatic targeting liposomes using microfluidics. J. Control Release. 307, 211–220 (2019).

Mondal, J. et al. Hybrid exosomes, exosome-like nanovesicles and engineered exosomes for therapeutic applications. J. Control Release. 353, 1127–1149 (2023).

Balboni, A. et al. Human glioblastoma-derived cell membrane nanovesicles: a novel, cell-specific strategy for Boron neutron capture therapy of brain tumors. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 19225 (2024).

Chng, W. H. et al. Extracellular vesicles and their mimetics: A comparative study of their Pharmacological activities and immunogenicity profiles. Pharmaceutics 15 (4), 1290 (2023).

De La Pena, H. et al. Artificial exosomes as tools for basic and clinical immunology. J. Immunol. Methods. 344 (2), 121–132 (2009).

Molinaro, R. et al. Design and development of biomimetic nanovesicles using a microfluidic approach. Adv. Mater. 30 (15), e1702749 (2018).

Sakai-Kato, K., Yoshida, K., Takechi-Haraya, Y. & Izutsu, K. I. Physicochemical characterization of liposomes that mimic the lipid composition of exosomes for effective intracellular trafficking. Langmuir 36 (42), 12735–12744 (2020).

Zhou, X. et al. Tumour-derived extracellular vesicle membrane hybrid lipid nanovesicles enhance SiRNA delivery by tumour-homing and intracellular freeway transportation. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 11 (3), e12198 (2022).

Lim, G. T. et al. Bioorthogonally surface-edited extracellular vesicles based on metabolic glycoengineering for CD44-mediated targeting of inflammatory diseases. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 10 (5), e12077 (2021).

Dooley, K. et al. A versatile platform for generating engineered extracellular vesicles with defined therapeutic properties. Mol. Ther. 29 (5), 1729–1743 (2021).

Allen, T. M. & Cullis, P. R. Liposomal drug delivery systems: from concept to clinical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv Rev. 65 (1), 36–48 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Centre for Applied Nanomedicine (CAN) at the RI-MUHC, led by Dr. Janusz Rak. We are grateful to members of his team, Nadim Tawil and Laura Montermini, for helping with training and experiments. We would also like to acknowledge Paola Rojas-Gutierrez from the laboratory of Dr. Larry Lands for providing training on DLS. We would like to thank Dr. Xin Su for assisting in confocal imaging. Finally we thanks Dr. Anas Alazzam from Khalifa University for providing the mold for the PDM.

Funding

We acknowledge the support of the Government of Canada’s New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRF) [NFRFE-2019-01587] to JVB. The study was also supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (to JVB [#190179]) and by National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (to VN [#177808]). Salary support was provided by Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS) (to JVB [#312831] and AB [#330312]), Canadian Graduate Scholarship (to TF [#476766]). TT received fundings from FRQS [#344929] with additional support from Gaden Phodrang Foundation, McGill University internal studentship and Fiera capital prize from the MUHC Foundation. YC received Master’s and PhD awards from the FRQS (#306252, #330509).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RL and CZ led the experimental work and contributed to manuscript writing. YC, TT, PB, ND, AE, TF, and AB contributed to experiments and manuscript writing. ND and KD analyzed data, created figures and drafted the manuscript. IS and CM provided scientific input. VN conceptualized the project, supervised students/staff and reviewed the manuscript. JVB conceptualized the project, acquired funding, supervised students/staff and drafted and reviewed the manuscript. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

López, R., Ben El Khyat, C., Chen, Y. et al. A synthetic model of bioinspired liposomes to study cancer-cell derived extracellular vesicles and their uptake by recipient cells. Sci Rep 15, 8430 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91873-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91873-5