Abstract

The dietary glycemic index (GI) reflects post-prandial plasma glucose generation rate, with higher-GI foods rapidly increasing blood sugar. Prenatal consumption of high-GI foods is associated with offspring risk for obesity and metabolic disorders. The impact of prenatal dietary GI exposure on infant neurodevelopment remains unclear. Maternal dietary intake, percent adiposity, and insulin resistance were prospectively assessed during the second and third trimesters in a sample of women with healthy, singleton pregnancies (N = 302). Infant negative affect was prospectively assessed at six months using observer ratings (Still Face Paradigm) and caregiver-reports (Infant-Behavior Questionnaire-Revised). Structural equation models assessed the independent effects of second and third trimester maternal dietary GI, adiposity, insulin resistance on infant negative affect, adjusted for relevant covariates. Higher third, but not second, trimester dietary GI was associated with increased observer-rated infant negative affect (β = 0.14, p = .04) and with higher caregiver-reported infant sadness (β = 0.17, p = .01), suggesting a programming effect of prenatal dietary GI on infant neurodevelopment. Targeted interventions that decrease dietary GI in later pregnancy may prove more effective for optimizing infant behavioral health compared to longer-term changes needed to alter metabolic state. Identifying modifiable early contributors to infant negative affect supports proactive strategies for mitigating future psychopathology risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The intrauterine environment has enduring consequences for infant development1,2, with growing evidence suggesting that prenatal environmental factors influence fetal brain development and thus shape infant temperament and behavioral trajectories3,4,5,6,7. Negative affect (NA)—the range of negative emotions indicating distress, discomfort, or dissatisfaction8—is a temperament trait of particular interest due to its emergence during early infancy as an indicator of socioemotional development9. Sustained and intense temperamental NA is associated with anxiety disorders, depression, and other psychological conditions10,11,12,13. Mounting evidence suggests that high infant NA is an early indicator of psychological vulnerability to later developmental psychopathology14. Prenatal nutrition and maternal metabolic state, including pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational weight gain (GWG), have been associated with child neurodevelopmental outcomes15, with infants born to mothers with higher pre-gravid BMIs exhibiting increased NA16, as well as difficulties with emotional regulation later in life17,18. Pre-gravid BMI and higher GWG are also associated with infant risk for neuropsychiatric disorders19,20,21, including risk for autism22,23,24,25, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)22,26, and affective disorders26,27,28. However, the mechanisms underlying the associations between maternal BMI and child neurodevelopment are unclear and have not been fully examined. Differences in prenatal nutrition29, exposure to different metabolic hormones (i.e. insulin15 and adipokines30), and increased exposure to chronic inflammation31 have all been postulated to play a role. [Note. In this work, the term ‘maternal’ is used to refer to individuals who are pregnant or have given birth to a child. We acknowledge that it may not fully describe the experiences of all individuals who fulfill the role of birthing parents].

Fetal exposure to hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia is also associated with neurodevelopmental consequences32,33,34. As fetal glucose requirements increase over the course of a typical pregnancy, maternal glucose uptake is naturally restricted to ensure adequate glucose availability for the fetus35. Upregulation of pancreatic processes leads to concomitant increases in maternal insulin secretion36. The effects of high glucose exposure and maternal insulin resistance on fetal body composition and cardiometabolic outcomes are well-documented37,38,39,40. Growing evidence suggests that prenatal exposure to hyperglycemia, as in gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), is associated with an increased risk for neuropsychiatric disease in offspring41, including risk for autism42,43 and ADHD44,45.

While emerging evidence indicates that chronic maternal metabolic conditions such as obesity and insulin resistance may influence infant temperament, the impact of acute metabolic events—specifically maternal post-prandial glucose surges—on infant neurodevelopment is understudied. Unlike chronic hyperglycemia, transient post-prandial spikes in glucose and increased variability in plasma glucose levels may pose a different set of challenges and possible risks to the developing fetus, potentially triggering rapid alterations in fetal insulin levels and metabolic responses, the effects of which may extend to the developing brain. One study examining the role of post-prandial glucose exposure on fetal brain activity using fetal magnetoencephalography (fMEG) in healthy pregnancies showed that fetuses of pregnant women with insulin resistance (but not GDM) had longer brain response latencies to auditory stimuli following an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), when compared to fetuses of pregnant women with greater insulin sensitivity46. Another study by the same group showed that the fetuses of pregnant women with GDM had slower post-prandial responses to auditory stimuli (measured by fMEG following an OGTT), when compared to fetuses from non-GDM pregnancies undergoing the same evaluation47.

Adequate prenatal nutrition is essential for supporting fetal development and reducing risk for cardiometabolic disease48,49,50 and psychopathology51. Conversely, certain prenatal dietary patterns are associated with increased offspring risk for disease52 and disorder16. Preclinical evidence suggests that prenatal dietary patterns high in saturated fats and sugar may have programming effects on offspring temperament53,54,55,56. There is growing evidence for prenatal dietary programming of neurodevelopment in humans57. For example, fetal exposure to prenatal diets high in total and saturated fats is associated with lower surgency and orienting/regulation at four-months58. Similarly, in contexts of higher prenatal stress, prenatal diets with lower omega-3:omega-6 ratios were linked to lower orienting/regulation in six-month-olds59, while prenatal diets low in antioxidants were linked to higher NA in 30-month-olds60. Together, these findings suggest that prenatal dietary patterns play a critical role in programming infant temperament.

The glycemic index (GI) is an indicator of diet quality that measures the amount and timing of post-prandial blood glucose release caused by individual foods61. Notably, results from other studies suggest that maternal pre-gravid BMI may not be associated with the GI, indicating its distinct contribution to the fetal environment62,63. Primarily derived from maternal carbohydrate intake, glucose is a significant energy source for the growing fetus, particularly the developing brain64. Diets high in refined carbohydrates have a higher GI, leading to sharper post-prandial glucose peaks, which may exacerbate the metabolic burden on the developing fetal brain. Higher-GI diets are linked to increased obesity and metabolic disorder risk in adults65,66 and emerging evidence suggests that fetal exposure to higher-GI diets during gestation is correlated with alterations in infant birthweight, body fat composition, and risk for metabolic disorders67,68,69,70. The consequences of higher-GI prenatal diets on infant neurobehavioral development are less well-understood. However, recent evidence shows that offspring exposed to maternal periconceptual diets with a high glycemic load ([GL] a metric that considers both the quality of the carbohydrate [as in the GI] and the quantity or portion size of the carbohydrate) exhibit more caregiver-reported signs of anxiety and inhibition as toddlers (approximately 14 months)71. These findings highlight the potential long-term consequences of maternal prenatal dietary patterns on infant temperament. Earlier work suggests that a three-day average for prenatal dietary GI is predictive of maternal plasma glucose concentrations62. In the present study, we collect three days of dietary GI in the second trimester and three days of dietary GI in the third trimester (six total), allowing us to examine the trimester-specific effects of dietary GI on offspring temperament development. Several recent reviews point out that the maternal prenatal diet is a modifiable risk factor72,73. However, despite its potential to inform intervention methods, to our knowledge, the association between maternal prenatal dietary GI and temperament in infancy has not been previously examined.

Prior to probing mechanistic effects and developing dietary interventions for optimizing the intrauterine environment, the independent effects of prenatal diet, adiposity, and insulin resistance require clarification. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), a powerful statistical tool for examining the distinct contributions of many factors to an outcome, we examined the following:

-

1.

Research Question 1: What are the distinct contributions of prenatal maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and insulin resistance on infant NA?

-

2.

Research Question 2: How does the prenatal timing of maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and insulin resistance influence infant NA?

To answer these questions, we estimated two SEMs (one examining maternal variables captured in the second trimester, the other examining maternal variables captured in the third trimester). Each model simultaneously accounted for the effects of prenatal maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and insulin resistance on infant NA at six months.

In the current study, we assessed infant NA using both observer ratings and caregiver reports. Assessing NA in both contexts is essential for gaining a comprehensive understanding of infant NA, as observer ratings and caregiver reports of this temperament dimension convey distinct information74. Observer reports offer an unbiased perspective, minimizing the influence of contextual factors, while caregiver ratings provide insights into the nuances of behavior within the familial setting. By utilizing both assessment methods, we capture a fuller spectrum of infant behavior, accounting for variations across contexts and ensuring a more holistic interpretation of temperament traits. Additionally, we adopt a fine-grained approach to infant temperament assessment, including carefully examining specific NA temperament domains, a key direction in identifying the specific emotional processes essential to understanding precursors of psychopathology75. Given evidence from preclinical53,54,55,56 and human studies16 that maternal dietary quality and adiposity may have distinct programming effects on infant sadness (propensity to display unhappiness or distress) and fear (distressed reaction to novel or unfamiliar situations), the sadness and fear domains of NA were of specific interest in this study.

Methods

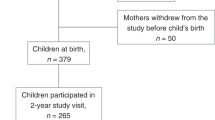

Data came from an ongoing, prospective longitudinal study examining the influence of maternal perinatal nutrition, adiposity, and metabolic state on infant neurodevelopment76,77. Participants were recruited beginning in 2018 at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU). Participants reported their dietary intake, completed an in-laboratory body composition assessment, and provided a fasting blood sample during the second (24–26 weeks’ gestation) and third (37–39 weeks’ gestation) trimesters. When infants were approximately six months old, caregivers completed infant temperament questionnaires and infants were observed for expressions of emotional regulation including NA, as part of a standardized battery of tests. See Fig. 1 for a study timeline. This study was conducted according to Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and was approved by the OHSU Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study timeline. Three 24-hour dietary recalls were conducted at each trimester (six total), as well as two body composition scans per trimester (four total) using air displacement plethysmography. A fasting blood sample was obtained during the second and third trimester (two total) from which HOMA-IR values were derived. Six months following delivery of infants, caregivers completed the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R) and infants were assessed using the Still Face Paradigm to determine infant temperament tendencies and propensities for negative affect.

Participants

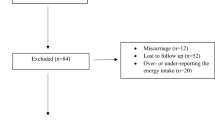

The present study included 302 participants. All pregnancies occurred between 2018 and 2021. Exclusionary criteria included: multiples pregnancies, known fetal anomaly or genetic condition affecting brain development or behavior, current substance use, use of medications affecting inflammation or with teratogenic effects, history of second- or third-trimester pregnancy loss and medical conditions affecting inflammation or confounded with obesity (e.g., Diabetes Type I/II, cancer, kidney disease, polycystic ovarian syndrome, bariatric surgery history, autoimmune diseases). See detailed recruitment information in Supplemental Methods and in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Measures

Dietary glycemic index

Prenatal dietary intake was measured by six unannounced, non-consecutive 24-hour recalls during the second and third trimester (3 recalls/trimester). Trained dietitians conducted recalls via the multi-pass method to record participant food and drink intake during the previous day78. The recalls were conducted over a two-week period, including two weekdays and one weekend day. The Nutrition Data System for Research software (NDSR, versions 2018–2020; University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota) was used to calculate the daily GI values for each participant by comparing the foods reported during recall to published sources79. Methods for assigning GI values to foods with unpublished values are described elsewhere80,81. All interviewers completed a training program and met qualification standards established in the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute Bionutrition Unit for using the NDSR software. All the GI values are expressed in relation to glucose (glucose = 100). The average GI values for the second and third trimesters were computed by summing the GI values of all foods reported on each recall day within a trimester and then averaging within each trimester. The second and third trimester GI averages were used in analyses.

Adiposity

Air displacement plethysmography was utilized via the BodPod® Body Composition tracking system (Life Measurement, Inc.) to measure second and third trimester body fat82,83. Participants fasted overnight and prior to testing and avoided exercise for three hours prior to testing. Participants wore skin-tight clothing and a swimming cap for testing. Following standard procedures, two 60-second measures were collected during both the second and third trimesters and the two measures were averaged within each trimester. As body fluid increases during pregnancy84, estimates of fat and lean mass were adjusted according to a validated equation85 and the adjusted second and third trimester pregnancy percent fat mass averages were utilized in analyses.

Insulin resistance

Fasting blood samples (44 mLs) captured via venipuncture during the second and third trimester were assayed for plasma glucose (mg/dL, colorimetric method—Stanbio Laboratories Inc., Boerne, TX 78006; mean coefficients of variation [%CV]; inter-assay: 2.8%, intra-assay: 1.5%, range: 20–450 mg/dL) and insulin (mU/L, commercially-available ELISA kits—Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden; %CV: inter-assay: 6.1%, intra-assay: 2.9%, range: 1-200 mU/L). The degree of maternal insulin resistance was calculated as the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance [HOMA-IR86), using the following equation: HOMA-IR = [fasting insulin (mU/L) x fasting glucose (mg/dL)] / 405. Extreme HOMA-IR scores (values > 6 SD above the mean) for two participants at each timepoint were excluded due to suspected non-fasting.

Infant outcomes

Observer ratings of negative affect: Still-Face Paradigm

Infant NA was assessed using the Still-Face Paradigm (SFP), a validated observational measure87 of infant distress during short-term disruptions in caregiver-infant interactions88. Blinded coders scored infants’ facial, vocal, and bodily distress during the Still Face episode of the SFP and the proportion of facial, vocal, and bodily distress exhibited by infants was calculated. Intensity modifiers (high, medium, low) were utilized to capture the intensity of SFP reactions. To focus on more pronounced reactions and allow for examination of heightened distress, the high- and medium-intensity codes were collapsed into a single category termed “medium-high” intensity to capture peak reactivity, as has been done previously89. See detailed coding information in the Supplementary Methods.

Prior to hypothesis testing, results from a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported considering the medium-high intensity distress measures (facial, vocal, and bodily distress) together as a latent variable representing overall infant NA (all loadings > 0.76, ps < 0.0001). See detailed information in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1.

Caregiver ratings of negative affect: Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised

Maternal reports of infant NA were measured using the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R). The IBQ-R is a widely-used, standardized instrument designed to explore the behavioral characteristics and temperament ratings of 3–12 month-olds8. Given their alignment with the dimensions of NA observed in the SFP and their value in identifying tendencies toward internalizing distress90, we focused our analyses solely on the sadness and fear subscales. The sadness subscale (α = 0.80) includes six items regarding behaviors reflecting sadness in infants, including questions regarding how often infants cry, show a gloomy facial expression, whimper or whine, or appear sad, downcast, or unhappy. The fear subscale (α = 0.92) includes six items regarding behaviors indicative of fear in infants, including becoming startled, displaying shyness, and avoiding novel situations. See detailed IBQ-R information in the Supplementary Methods.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic occurring during data collection for this study, we shifted to remote data collection methods76 after pandemic onset and continued to offer remote options after pandemic restrictions were relaxed. Thus, location of assessment (remote or in-person) and perceived stress during pregnancy (Perceived Stress Scale91) were considered in all analyses. See Covariates section below for details. Notably, a review of medical records indicated that no participants tested positive for COVID-19 during pregnancy.

Covariates

Covariates were considered based on their potential to influence maternal dietary or metabolic health during pregnancy, infant behavioral outcomes, or maternal temperament ratings7,91,92,93,94,95,96. Maternal age at last menstrual period was considered (M = 31.94 years, range = 17.84–40.28 years), along with parity. Parity values in our sample included 0 (n = 170, 56.3%), 1 (n = 91, 30.1%), 2 (n = 24, 7.9%), 3 (n = 7, 2.3%), and 4 (n = 2, 0.7%), or Unknown (n = 17, 5.6%) and were categorized into primiparous (n = 170, 56.3%) or multiparous (n = 124, 41.1%). Eight participants (2.6%) had missing or unreported parity data. Maternal race and ethnicity were also considered. Participants identified as Asian (n = 24, 7.9%), Black (n = 4, 13.2%), Multiracial (n = 32, 10.6%), Native American (n = 3, 0.9%), Pacific Islander (n = 1, 3.3%), White (n = 235, 77.7%), Other (n = 2, 0.7%) or Missing/Not Reported/Unknown (n = 10, 3.3%). Participants also reported whether they identified as Hispanic (n = 25, 8.3%), non-Hispanic (n = 277, 9.2%), with 9 participants (3.0%) missing data. Given the low rates of specific racial/ethnic groups, race and ethnicity were combined and categorized into White, non-Hispanic (n = 221, 73.2%) or racial/ethnic minority (n = 81, 26.8%) for analyses. Prenatal stress, measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)97 during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, was also considered as a covariate. Synthetic insulin use (Yes = 15, 5.05%; No = 279, 92.4%) was also considered. As two participants reported metformin use during pregnancy, a combined variable of prenatal synthetic insulin/metformin use was used as a covariate in analyses, with twenty-four participants (7.9%) having missing or unreported data. We also considered self-reported prenatal vitamin use, with any prenatal vitamin supplementation in the second or third trimester (Yes = 270, 89.4%; No = 9, 3.0%) considered as a covariate in analyses. Twenty-three participants (7.6%) had missing or unreported prenatal vitamin use data. Participants self-reported information about their socioeconomic status at enrollment and at 37-weeks’ gestation, including total household income, via the following question, “Which of these categories best describes your total combined family income for the past 12 months?” Categories included: 1 = Less than $5000, 2=$5,000 through $11,999, 3=$12,000 through $15,999, 4=$16,000 through $24,000, 5=$25,000 through $34,000, 6=$35,000 through $49,999, 7=$50,000 through $74,000, 8=$75,000 through $99,999, 9=$100,000 through $199,999, 10=$200,000 through $299,999, 11=$300,000 and greater. The mean value from each of these brackets was calculated and divided by the number of people living in the household and used in analyses. For those reporting $300,000 and greater (n = 17, 5.6%), $300,000 was used in calculations. For those reporting less than $5,000 (n = 2, 0.7%), $5,000 was used in calculations.

Infant birthweight was captured at delivery and birthweight percentiles were considered in analyses. Infants in our study were classified as being at or below the 10th percentile (n = 21, 7.0) or at or above the 90th percentile (n = 39, 12.9%), based on recommendations provided by the World Health Organization98. All other infants’ birthweights were between the 10th and 90th percentile (n = 237, 78.5%). Birthweight percentiles were missing for five individuals (1.7%). All postnatal assessments occurred when infants were approximately six months of age (Mage: 6.39 months, SD: 0.55 months; Mode: 6.01 months; Range: 5.32–9.17 months); however, due to the range, infant age at assessment was considered as a covariate. Observational assessments of infant temperament were conducted either in-laboratory (n = 90, 29.8%) or remotely over video conferencing software (n = 160, 53.0%). Thus, we considered assessment location as a covariate in all analyses involving the SFP. The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)99 was used to capture maternal mood at six months post-delivery and maternal CES-D score at six months post-delivery was included as a covariate in all models examining maternal-reports of infant NA. Analyses also considered infant feeding practices at six months assessed at via the Infant Feeding and Sleeping Questionnaire100 (e.g., Are you currently breastfeeding or feeding your child pumped breast milk?; Yes: n = 226, 74.8% of sample). Forty-six participants (15.2%) had missing or unreported data for this variable.

Sensitivity analyses: Gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis and dietary glycemic load

A subset of participants was diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM; Yes: n = 27, 8.9%). While primary analyses incorporated prenatal use of synthetic insulin (a recommended GDM-management strategy101), we conducted sensitivity analyses covarying GDM diagnosis status. The predictor variables considered in this sensitivity analysis remained consistent with the primary analyses, including maternal adiposity, HOMA-IR, and dietary GI captured during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

To examine whether portion size, in addition to carbohydrate quality, contributes to infant NA, we also conducted sensitivity analyses incorporating second and third trimester maternal dietary GL in place of dietary GI. Other predictor variables remained consistent with the primary analyses, including maternal adiposity and HOMA-IR during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy.

Analytic strategy

A major goal of this study was to examine the unique contributions of each focal predictor (maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and HOMA-IR) on infant NA. One challenge associated with disentangling these unique effects is that these metrics of maternal metabolic state are typically correlated with one another. To address this, we elected to test our hypotheses using structural equation modeling (SEM), a statistical framework that allowed us to estimate the intercorrelations among focal variables while simultaneously examining their unique effects on infant NA. Models were estimated using Mplus (v.8; Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2021) using the robust maximum likelihood estimator, which can accommodate non-normal data by adjusting standard errors using the Huber-White sandwich estimator. Missing data were addressed using full information maximum likelihood (FIML), consistent with best practices for handling missing data102. This allowed us to utilize all available data in our analyses (N = 302). Model fit was assessed by examining the comparative fit index (CFI; adequate fit was considered as CFI ≥ 0.90), the Tucker Lewis index (TLI; adequate fit was considered as TLI ≥ 0.90), the standard root mean square residual (SRMR; adequate fit was considered as SRMR ≤ 0.05), and the root mean squared error of the approximation (RMSEA; adequate fit was considered as RMSEA ≤ 0.08)103,104. The Mplus cluster command was used to account for non-independent observations (i.e., participants who were followed across multiple pregnancies; n = 5).

Candidate covariates included maternal age, parity, minoritized race/ethnicity, prenatal stress, synthetic insulin/metformin use, prenatal vitamin use, household income (adjusted for household size), infant birthweight percentiles, and age at six-month assessment, SFP assessment location, maternal CES-D score at six months The following approach was used to address our research questions:

-

1.

Bivariate Correlations, t-Tests, ANOVA, and Covariate Selection. Bivariate correlations examined the associations among focal variables. Associations between focal variables and candidate continuous covariates were assessed using bivariate correlations, while t-tests were used to compare continuous focal variables across dichotomous categorical covariates. For covariates with more than two categories, comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA. Covariates with significant associations (p < .05) with prenatal adiposity, dietary GI, HOMA-IR values, or infant NA were incorporated into models used to test our research questions.

-

2.

Research Questions 1 and 2: Research Question 1 (What are the distinct contributions of prenatal maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and insulin resistance on infant NA?) was addressed using an SEM in which observer ratings of infant NA as well as caregiver-reported infant sadness and fear were simultaneously regressed on maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and HOMA-IR during pregnancy. Dietary GI, adiposity, and HOMA-IR were allowed to covary. Covariates identified in Step 1 were included in this model, with paths estimated from each covariate to dietary GI, adiposity, HOMA-IR, and infant NA. To address Research Question 2 (How does the prenatal timing of maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and insulin resistance influence infant NA?), models were run twice: once considering second trimester variables and again considering third trimester variables. Given its direct role in influencing HOMA-IR, prenatal use of synthetic insulin use was included in all models. To preserve model parsimony, for all other candidate covariates, non-significant paths from covariates were removed from final models.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Demographic information and descriptive statistics appear in Table 1.

Bivariate correlations

Second trimester HOMA-IR was positively correlated with observer ratings of infant NA at six months (r = .20, p = .01) and caregiver rated infant fear from the IBQ-R (r = .23, p = .003). Caregiver rated infant sadness from the IBQ-R was correlated with greater third trimester GI (r = .14, p = .04). See Table 2 for detailed correlations between focal variables and continuous covariates.

T-tests and ANOVA

Comparisons of focal variables (e.g., second and third trimester adiposity [% body fat mass], dietary GI, and HOMA-IR values, as well as infant NA and the sadness and fear subscales) were conducted using t-tests for two-category covariates and one-way ANOVA for covariates with three categories. Detailed comparisons are provided in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Tables 2–5.

Participants with a GDM diagnosis exhibited significantly higher adiposity (second trimester: p < .001, third trimester: p < .001), higher dietary GI (second trimester: p = .02, third trimester: p = .04), and higher HOMA-IR values (second trimester: p < .001, third trimester: p < .001), compared to those without a GDM diagnosis. Similarly, compared to those not using synthetic insulin, participants using synthetic insulin had higher adiposity (second trimester: p < .001, third trimester: p < .001), higher dietary GI (second trimester: p = .03, third trimester: p = .004), and higher HOMA-IR values (second trimester: p = .01, third trimester: p < .001). Compared to those who continued breastfeeding at six months postpartum, participants who discontinued breastfeeding had higher adiposity (second trimester: p < .001, third trimester: p = .002), higher third trimester dietary GI (second trimester: p = .14, third trimester: p < .001), and higher second trimester HOMA-IR values (second trimester: p < .001, third trimester: p = .64). Infants tested remotely during the SFP exhibited higher NA, compared to those tested in the laboratory (p < .001).

Maternal adiposity, dietary GI, and HOMA-IR and infant NA

Observer-rated and caregiver-reported infant NA was first regressed on second trimester maternal HOMA-IR, dietary GI, and adiposity and then again on third trimester variables. All final models fit the data adequately. Results from final models are detailed below.

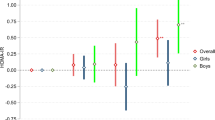

Second trimester variables and Observer-Reports and Caregiver-Ratings of infant NA

The second trimester model fit the data adequately (χ²(df = 20) = 32.52, p = .04; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.05). After accounting for the intercorrelations among second trimester adiposity, dietary GI, and HOMA-IR, as well as between observer-rated infant NA and caregiver-reported infant fear sadness and fear, there was a significant association between second trimester HOMA-IR and caregiver-reported infant fear at six months (β = 0.27, [95% CI: 0.09, 0.46], p = .003). Second trimester PSS, synthetic insulin and/or metformin use, and SFP assessment location were retained as covariates in the final model. See Fig. 2 for details. There were no other significant associations between second trimester HOMA-IR and other measures of infant NA (Observer-reported NA: β = 0.23, p = .11; Sadness subscale: β=-0.003, p = .98). There were no significant associations between second trimester adiposity on infant NA (Observer-reported NA: β=-0.06, p = .54; Sadness subscale: β=-0.10, p = .37; Fear subscale: β=-0.01, p = .88) or between second trimester dietary GI and infant NA (Observer-reported NA: β = 0.05, p = .36; Sadness subscale: β = 0.07, p = .31; Fear subscale: β = 0.05, p = .47).

Second trimester HOMA-R predicts caregiver-reported infant fear at six months (N = 302). Results from structural equation model testing the independent effects of second trimester maternal adiposity, dietary glycemic index, and homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) on observer and caregiver ratings of infant NA at six months. This model fit the data adequately (Model fit statistics: χ²(df = 20) = 32.52, p = .04; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.95; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.05). Second trimester HOMA-IR independently predicted caregiver-reported infant fear at six months (β = 0.27, [95% CI: 0.09, 0.46], p = .003). Final model estimates were adjusted for second trimester perceived stress scale (β = 0.24, [95% CI: 0.11, 0.36], p < .0001), synthetic insulin and/or metformin use (βs > -0.08, ps < 0.61), and assessment location (β = 0.24, [95% CI: 0.10, 0.37], p = .001). *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Third trimester variables and Observer-Reports and Caregiver-Ratings of infant NA

The third trimester model fit the data adequately (χ²(df = 29) = 61.58, p = .001; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.91; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.06). After accounting for the intercorrelations among third trimester adiposity, GI, and HOMA-IR, as well as between observer-rated infant NA and caregiver-reported infant fear sadness and fear, there was a significant association between third trimester dietary GI and observer-ratings of NA at six months (β = 0.14, [95% CI: 0.01, 0.27], p = .04). There was also a significant association between third trimester dietary GI and caregiver-reported infant sadness at six months (β = 0.17, [95% CI: 0.04, 0.29], p = .01). Maternal age, third trimester PSS, synthetic insulin and/or metformin use, infant age at NA testing, and SFP assessment location were retained as covariates in the final model. See Fig. 3 for details. There were no significant associations between third trimester dietary GI and caregiver-reported infant fear (β=-0.04, p = .64). There were no significant associations between third trimester adiposity and infant NA (Observer-reported NA: β=-0.11, p = .12; Sadness subscale: β=-0.004, p = .97; Fear subscale: β = 0.10, p = .26) or third trimester HOMA-IR and infant NA (Observer-reported NA: β = 0.04, p = .50; Sadness subscale: β=-0.17, p = .20; Fear subscale: β = 0.01, p = .93).

Third trimester dietary glycemic index predicts observer-reported infant negative affect and caregiver-reported infant sadness at six months (N = 302). Results from structural equation model testing the independent effects of third trimester maternal adiposity, dietary glycemic index (GI), and homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) on observer and caregiver ratings of infant NA at six months. This model fit the data adequately (χ²(df = 29) = 61.58, p = .001; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.91; SRMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.06). Third trimester dietary GI independently predicted observer-ratings of NA at six months (β = 0.14, [95% CI: 0.01, 0.27], p = .04). There was also an association between third trimester dietary GI and caregiver-reported infant sadness at six months (β = 0.17, [95% CI: 0.04, 0.29], p = .01). Final model estimates were adjusted for maternal age (β = -0.14, [95% CI: -0.27, -0.01], p = .04), perceived stress scale (β = 0.16, [95% CI: 0.04, 0.28], p = .01), synthetic insulin and/or metformin use (βs > 0.12, ps < 0.21), infant age at NA testing (β = -0.16, [95% CI: -0.29, -0.04], p = .01), and assessment location (β = 0.25, [95% CI: 0.11, 0.39], p = .0001). *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Sensitivity analyses examined whether these effects survived considering whether participants were diagnosed with GDM (n = 27). Results were consistent in significance, magnitude, and direction with the main models reported. See Supplementary Results and Supplementary Tables 6–7 for detailed results. Sensitivity analyses also examined whether the observed effects were associated with portion size by assessing the association between maternal dietary GL on infant NA. Results from these models were non-significant. See Supplementary Results and Supplementary Tables 8–9 for detailed results.

Discussion

Maternal diet and metabolic health during pregnancy exert profound programming effects on offspring developmental trajectories, including future psychopathological risk29,33,105. Identifying the distinct programming roles of maternal prenatal nutrition, body composition, and insulin sensitivity on infant risk for neurodevelopmental disorders is critical for identifying key intervention targets and timepoints, and necessarily requires the consideration of their complex interplay. Here, we examined the associations between prenatal maternal dietary GI, adiposity, and HOMA-IR and infant NA, an early risk factor for future psychopathology. We sought to disentangle the unique contributions of each factor on infant NA at six months. Our findings revealed a significant link between higher third trimester dietary GI and increased infant NA, an association observed in both maternal-reports of infant sadness, a fine-grained temperament domain of NA, and observer-ratings of infant behavioral NA, underscoring the robustness of this effect. These same associations were not observed for variables captured in the second trimester, suggesting a potential sensitive period for when dietary GI-related fetal programming of infant NA occurs.

Accumulating preclinical53,54,55,56 evidence and evidence from human studies16 suggests that maternal dietary quality and adiposity may have programming effects on infant NA, and particularly, on high rates of sadness and fear, which are associated with later psychopathology106. Caregiver-reported measures in this study suggested that prenatal high-GI diet’s effects on infant NA may be specific to infant sadness, suggesting that offspring exposed to higher-GI prenatal diets may have broad tendencies toward future internalizing disorders.

That the third, but not second, trimester dietary GI was associated with infant NA highlights the importance of considering timing effects when examining prenatal maternal dietary influences on infant neurodevelopment107,108. The timing and impact of maternal dietary GI on fetal neurodevelopment are especially pertinent as maternal glucose serves as the primary fuel source to the fetal brain64. The unique metabolic demands of the third trimester may create an environment in which higher-GI diets exert more pronounced effects on infant development109. The fetal brain may have heightened vulnerability to nutritional influences during the third trimester due to its substantial energy requirements throughout this period109. The third trimester is a period of rapid maturation, including synaptogenesis and synaptic refinement110,111. This interpretation is supported by the increased nutrient demands during the third trimester112, including for polyunsaturated fatty acids and choline, both of which are critical for brain development113,114. In contrast, the second trimester is marked by neurogenesis and neuronal migration110, including rapid growth of fetal white matter, deep subcortical structures, and the cerebellum115, potentially laying the neural groundwork as a precursor to the more intricate aspects of emotional regulation. We note our finding of a significant effect of second, but not third, trimester HOMA-IR on caregiver-reported infant fear at six months, which may suggest that the various aspects of infant temperament, and domains of NA in particular, are impacted differentially by maternal metabolic health factors at different times during pregnancy.

The distinction between insulin resistance, reflecting chronic glycemic control116, and dietary GI, reflecting plasma glucose concentrations following specific food intake117 is crucial. Both adiposity and insulin resistance may result from chronic high GI food consumption; however, chronic but steady increases in insulin resistance and accumulation of adipose tissue may allow for gradual fetal adaptation to the intrauterine environment, whereas frequent glucose exposure fluctuations from higher-GI diets118 may present a less optimal fetal environment, leading to distinct programming effects on the fetus.

Our findings contribute to mounting evidence that maternal diet during the periconceptual and perinatal periods plays a critical programming role in infant and toddler temperament and behavioral outcomes58,59,60,71. Previous research demonstrated that higher maternal dietary GL at a single timepoint surrounding conception was associated with reductions in toddler socioemotional functioning measured using the Infant-Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment71. We extend these findings in our study by repeatedly measuring maternal dietary GI throughout pregnancy using six 24-hour dietary recalls and identifying an association between third trimester maternal dietary GI and infant caregiver-rated and observer-reported NA at six months. Taken together, these studies suggest that the glycemic quality of the maternal diet during these key periods has programming effects on offspring neurodevelopmental health, with maternal consumption of a more glycemic periconceptual and prenatal diet associated with increased risk for offspring developmental psychopathology.

Beyond glycemic measures, other components of the prenatal maternal diet are emerging as important to infant temperament and behavioral health, While pregnant women’s self-reported 24-hour total dietary fat intake did not appear to influence caregiver-reported NA, it was associated with lower orienting/regulation and surgency in four month olds58. In addition to the total amount of fat consumed, evidence highlights the importance of the type of fatty acid consumed, with higher maternal dietary omega-3:omega-6 ratio captured via a FFQ early in pregnancy linked to higher caregiver-reported infant orienting/regulation at six months old, but only in contexts of higher maternal prenatal stress59. Higher plasma concentrations of omega-3 fatty acids during the third trimester are also associated with lower infant NA at six months, measured via maternal-reports and observer-ratings16. Furthermore, maternal dietary antioxidant consumption has also been linked to child behavior, with higher consumption of dietary antioxidants measured via FFQ in early pregnancy associated with higher caregiver-reported surgency (e.g., vitamin C and selenium) and caregiver-reported effortful control (e.g., vitamin C) in 30-month-olds60. The same study found that an association between prenatal stress and caregiver-reported NA in offspring was exacerbated among children of mothers with lower prenatal antioxidant intake.

Mechanistic studies in animal models further underscore that maternal dietary patterns (especially diets high in fat and sugar) influence offspring susceptibility to depressive- or anxiety-like phenotypes53,56,119. Taken together, these studies emphasize the important role of maternal prenatal diet composition in programming offspring temperament and behavioral health, with specific dietary components appearing to differentially affect offspring neurodevelopmental domains throughout the phases of pregnancy, underscoring the role of maternal diet as a key, modifiable factor in fetal programming of emotional development and regulation.

It is important to consider what the dietary GI reflects. The dietary GI reflects how quickly the blood glucose increases following the consumption of an individual food. Notably, our use of a three-day average of the dietary GI during pregnancy is supported by prior work that shows that the dietary GI is predictive of important markers of maternal carbohydrate metabolism, including both plasma glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c])62, a form of hemoglobin chemically linked to glucose, representing the average blood glucose over the prior 2–3 months120. In non-pregnant samples, studies show that the dietary GI is also predictive of other glycemic response indicators121. Prior work also indicates that the prenatal dietary GI is associated with infant birth outcomes62. Dietary GI is associated with fluctuations in blood glucose118, which might have unique implications for fetal development.

Another measure of glycemic impact is the dietary GL, which adjusts for serving size and the span of the blood glucose increase. We found that maternal prenatal dietary GI but not GL in the third trimester was predictive of infant NA at six months (Supplementary Results and Supplementary Tables 8–9), suggesting that the glycemic nature of the food consumed has developmental programming effects on the fetus, rather than the serving size or the numbers of calories of the glycemic foods consumed. Prior work shows that maternal dietary GL has a weaker association with glycosylated hemoglobin in pregnant women and does not have an association with plasma glucose or with infant birth outcomes62. However, this may not offer a full explanation, as the aforementioned study examining the role of maternal dietary GL on offspring socioemotional development showed that higher maternal periconceptual dietary GL was associated with anxiety and inhibition in toddlers71. It is worth noting, however, that in this prior study only a single capture of maternal dietary GL was utilized, and was calculated using a food frequency questionnaire concerning eating habits during the last menstrual period before pregnancy, which may be a limited representation of the day-to-day maternal diet. It is also possible that this discrepancy in findings between maternal dietary GI in our study and maternal dietary GL in the previous study is due to participant difficulties in accurately recalling and/or reporting portion sizes, as opposed to simply recalling the specific foods they consumed, limiting the fidelity of the dietary GL measure. Discrepancies between study outcomes when assessing dietary GI versus dietary GL may also be explained by studies in pregnant women show that there is a chronic underreporting of daily energy intake, particularly among women with higher BMIs122,123. Dietary GI and GL have also been associated with methylation of different genes in cord blood124, which may result in different pathways toward similar temperament and behavioral outcomes, offering another potential explanation of these findings.

Consideration of the precise molecular mechanisms underlying these associations is needed. One compelling mechanism is inflammation, with higher-GI foods triggering an inflammatory response via repeatedly elevating maternal blood glucose concentrations and impacting fetal neurodevelopment125. Alternatively, or in addition, oxidative stress may result from fluctuating maternal blood glucose levels126,127, leading to cellular damage and potential consequences for the developing fetal brain. Dietary influences on cord blood DNA methylation patterns124 may also indicate cascading epigenetic effects on infant neurodevelopment. Another interesting possibility is that the maternal prenatal diet may alter the maternal microbiome, which may have programming effects on infant temperament, as in two recent studies128,129.

Study strengths include our use of objective measures including repeated, nutritionist-conducted 24-hour recalls (three days in the second and third trimesters [six total]), BodPod® assessment of adiposity, and determining HOMA-IR from blood samples captured within two weeks of the other measures. Our data collection procedures allowed us to examine trimester-specific effects, resulting in the findings that second trimester HOMA-IR predicts infant fear, while third trimester dietary GI predicts infant NA, highlighting the need for more studies examining the timing of prenatal influences on infant neurodevelopment. Another strength is our use of a three-day average to measure prenatal dietary GI which has been previously shown to be predictive of glucose measured in maternal plasma62. Previous evidence indicates that prenatal dietary GI influences neonatal body composition outcomes, with neonates of mothers who consumed low-GI diets giving birth to infants with lower weights69. The data presented in this study extend these findings by examining the influence of prenatal dietary GI on infant neurodevelopmental outcomes in six months olds. Our study also incorporated longitudinal dietary data from the second and third trimesters, as well as infant feeding practices at six months (74.8% of infants were still breastfed at six months). SEM is a strong analytic approach used to disentangle each predictor’s independent contributions while controlling for confounding covariates130. Furthermore, by incorporating well-established methods of assessing objective (SFP)87,88 and subjective (IBQ-R) NA8, we comprehensively assessed infant temperament, bolstering the findings.

Limitations should also be considered. First, as the observed effects were relatively small in magnitude, these findings should be replicated in larger samples. Future research should explore the underlying mechanisms and long-term implications of these associations, including considering the role of the postnatal diet, which has important implications for infant development105. Future studies specifically examining perinatal dietary trajectories from conception through the postpartum period are warranted to better characterize the timing effects of nutrition on child temperament and behavior. Future work may benefit from using continuous glucose monitoring during pregnancy as a tighter measure of the daily fluctuations in blood glucose to further clarify the associations between the prenatal dietary GI and infant temperament development. Future studies evaluating the contributions of the prenatal dietary GI and GL on offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes may also benefit from using more frequently assessed dietary recalls, using dietary recalls assessed at other times during the periconceptual or perinatal period, or using weighed food diaries as alternatives.

In conclusion, this study underscores the significance of maternal dietary quality during pregnancy, particularly third trimester dietary GI, in optimizing infant neurodevelopmental health. Clinically, maternal body composition and pancreatic physiology may represent more challenging intervention targets, unlike the glycemic nature of the diet itself, which may be more readily modifiable131. Developing targeted dietary interventions that involve exchanging high-GI foods for lower-GI replacements may be a feasible means of enhancing infant neurodevelopmental health and well-being. To the extent that infant NA is associated with future psychopathology, our findings represent important preliminary evidence for the third trimester as a critical window for maternal dietary quality to exert programming effects on infant temperament and point to the dietary GI as a potential intervention target for reducing risk for future psychiatric concerns. These findings have implications for clinical practice and public health and highlight the value of recommending maternal dietary modifications at specific pregnancy stages.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available via the National Institute of Mental Health Data Archive (https://nda.nih.gov/), collection C2996.

References

Barker, D. J. P. The developmental origins of adult disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 23, 588S–595S (2004).

Lau, C., Rogers, J. M., Desai, M. & Ross, M. G. Fetal programming of adult disease: implications for prenatal care. Obstet. Gynecol. 117, 978–985 (2011).

Gartstein, M. A. & Skinner, M. K. Prenatal influences on temperament development: the role of environmental epigenetics. Dev. Psychopathol. 30, 1269–1303 (2018).

Nolvi, S. et al. Maternal prenatal stress and infant emotional reactivity six months postpartum. J. Affect. Disord. 199, 163–170 (2016).

Gustafsson, H. C. et al. Maternal prenatal depression predicts infant negative affect via maternal inflammatory cytokine levels. Brain. Behav. Immun. 73, 470–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.06.011 (2018).

Werner, E. et al. Higher maternal prenatal cortisol and younger age predict greater infant reactivity to novelty at 4 months: an observation-based study. Dev. Psychobiol. 55, 707–718 (2013).

Baibazarova, E. et al. Influence of prenatal maternal stress, maternal plasma cortisol and cortisol in the amniotic fluid on birth outcomes and child temperament at 3 months. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38, 907–915 (2013).

Gartstein, M. A. & Rothbart, M. K. Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behav. Dev. 26, 64–86 (2003).

Nigg, J. T. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 47, 395–422 (2006).

Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M. & Hooe, E. S. Relations of positive and negative affectivity to anxiety and depression in children: evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 71, 465 (2003).

Gartstein, M. A. & Bateman, A. E. Early manifestations of childhood depression: influences of infant temperament and parental depressive symptoms. Infant Child. Development: Int. J. Res. Pract. 17, 223–248 (2008).

Grant, V. V., Bagnell, A. L., Chambers, C. T. & Stewart, S. H. Early temperament prospectively predicts anxiety in later childhood. Can. J. Psychiatry. 54, 320–330 (2009).

Keenan, K. Emotion dysregulation as a risk factor for child psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 7, 418 (2000).

Kostyrka-Allchorne, K., Wass, S. V. & Sonuga‐Barke, E. J. Research review: do parent ratings of infant negative emotionality and self‐regulation predict psychopathology in childhood and adolescence? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 61, 401–416 (2020).

Edlow, A. G. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenat. Diagn. 37, 95–110 (2017).

Gustafsson, H. C. et al. Increased maternal prenatal adiposity, inflammation, and lower omega-3 fatty acid levels influence child negative affect. Front. NeuroSci. 13, 1035 (2019).

Robinson, M. et al. Pre-pregnancy maternal overweight and obesity increase the risk for affective disorders in offspring. J. Dev. Origins Health Disease. 4, 42–48 (2013).

Rodriguez, A. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and risk for inattention and negative emotionality in children. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 51, 134–143 (2010).

Kong, L., Norstedt, G., Schalling, M., Gissler, M. & Lavebratt, C. The risk of offspring psychiatric disorders in the setting of maternal obesity and diabetes. Pediatrics 142, e20180076 (2018).

Rivera, H. M., Christiansen, K. J. & Sullivan, E. L. The role of maternal obesity in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. Front. NeuroSci. 9, 194. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2015.00194 (2015).

Chen, S. et al. Rates of maternal weight gain over the course of pregnancy and offspring risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. BMC Med. 21, 108 (2023).

Andersen, C. H., Thomsen, P. H., Nohr, E. A. & Lemcke, S. Maternal body mass index before pregnancy as a risk factor for ADHD and autism in children. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 27, 139–148 (2018).

Getz, K. D., Anderka, M. T., Werler, M. M. & Jick, S. S. Maternal Pre-pregnancy body mass index and autism spectrum disorder among offspring: A Population‐Based Case–Control study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 30, 479–487 (2016).

Su, L. et al. Association between gestational weight gain and autism spectrum disorder in offspring: a meta-analysis. Obesity 28, 2224–2231 (2020).

Windham, G. C. et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain in relation to autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disorders in offspring. Autism Res. 12, 316–327 (2019).

Pugh, S. et al. Gestational weight gain, prepregnancy body mass index and offspring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and behaviour at age 10. BJOG: Int. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 123, 2094–2103 (2016).

Van Lieshout, R. J., Robinson, M. & Boyle, M. H. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and internalizing and externalizing problems in offspring. Can. J. Psychiatry. 58, 151–159 (2013).

Tore, E. C. et al. Gestational weight gain by maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and childhood problem behaviours in school-age years: a pooled analysis of two European birth cohorts. Matern. Child Health J. 24, 1288–1298 (2020).

Bordeleau, M., Fernandez de Cossio, L., Chakravarty, M. M. & Tremblay, M. È. From maternal diet to neurodevelopmental disorders: a story of neuroinflammation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 14, 612705 (2021).

Sullivan, E. L. et al. Adipokines measured during pregnancy and at birth are associated with infant negative affect. Brain. Behav. Immun. 120, 34–43 (2024).

van der Burg, J. W. et al. The role of systemic inflammation linking maternal BMI to neurodevelopment in children. Pediatr. Res. 79, 3–12 (2016).

Chen, S., Zhao, S., Dalman, C., Karlsson, H. & Gardner, R. Association of maternal diabetes with neurodevelopmental disorders: autism spectrum disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability. Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 459–474 (2021).

e Silva, R. N. A. et al. Associations of maternal diabetes during pregnancy with psychiatric disorders in offspring during the first 4 decades of life in a population-based Danish birth cohort. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2128005–e2128005 (2021).

Lotfi, N., Hami, J., Hosseini, M., Haghir, D. & Haghir, H. Diabetes during pregnancy enhanced neuronal death in the hippocampus of rat offspring. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 51, 28–35 (2016).

Lain, K. Y. & Catalano, P. M. Metabolic changes in pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 50, 938–948 (2007).

Sonagra, A. D., Biradar, S. M., Dattatreya, K. & DS, J. M. Normal pregnancy-a state of insulin resistance. J. Clin. Diagn. Research: JCDR. 8, CC01 (2014).

Lowe, W. L. et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcome Follow-up study (HAPO FUS): maternal gestational diabetes mellitus and childhood glucose metabolism. Diabetes Care. 42, 372–380. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-1646 (2019).

Sauder, K., Hockett, C., Ringham, B., Glueck, D. & Dabelea, D. Fetal overnutrition and offspring insulin resistance and β-cell function: the exploring perinatal outcomes among children (EPOCH) study. Diabet. Med. 34, 1392–1399 (2017).

Lima, R. A. et al. The importance of maternal insulin resistance throughout pregnancy on neonatal adiposity. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 35, 83–91 (2021).

Hamilton, J. K. et al. Maternal insulin sensitivity during pregnancy predicts infant weight gain and adiposity at 1 year of age. Obesity 18, 340–346 (2010).

Rodolaki, K. et al. The impact of maternal diabetes on the future health and neurodevelopment of the offspring: a review of the evidence. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1125628 (2023).

Sacks, K. N. et al. Prenatal exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for long-term neuropsychiatric morbidity of the offspring. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 215, 380 (2016). e381-380. e387.

Xiang, A. H. et al. Maternal type 1 diabetes and risk of autism in offspring. Jama 320, 89–91 (2018).

Nomura, Y. et al. Exposure to gestational diabetes mellitus and low socioeconomic status: effects on neurocognitive development and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 166, 337–343 (2012).

Xiang, A. H. et al. Maternal gestational diabetes mellitus, type 1 diabetes, and type 2 diabetes during pregnancy and risk of ADHD in offspring. Diabetes Care. 41, 2502–2508 (2018).

Linder, K. et al. Maternal insulin sensitivity is associated with oral glucose-induced changes in fetal brain activity. Diabetologia 57, 1192–1198 (2014).

Linder, K. et al. Gestational diabetes impairs human fetal postprandial brain activity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 100, 4029–4036 (2015).

Pool, L. R. et al. Childhood risk factors and adulthood cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. J. Pediatr. 232, 118–126 (2021).

Salam, R. A. et al. Effects of lifestyle modification interventions to prevent and manage child and adolescent obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 12, 2208 (2020).

Carolan-Olah, M., Duarte‐Gardea, M. & Lechuga, J. A critical review: early life nutrition and prenatal programming for adult disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 24, 3716–3729 (2015).

Monk, C., Lugo-Candelas, C. & Trumpff, C. Prenatal developmental origins of future psychopathology: mechanisms and pathways. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 15, 317–344 (2019).

Sen, S. et al. Associations of prenatal and early life dietary inflammatory potential with childhood adiposity and cardiometabolic risk in project Viva. Pediatr. Obes. 13, 292–300 (2018).

Sullivan, E. L. et al. Chronic consumption of a high-fat diet during pregnancy causes perturbations in the serotonergic system and increased anxiety-like behavior in nonhuman primate offspring. J. Neurosci. 30, 3826–3830 (2010).

Thompson, J. R. et al. Exposure to a high-fat diet during early development programs behavior and impairs the central serotonergic system in juvenile non-human primates. Front. Endocrinol. 8, 164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00164 (2017).

Thompson, J. R. et al. Maternal diet, metabolic State, and inflammatory response exert unique and long-lasting influences on offspring behavior in non-human primates. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2018.00161 (2018).

Mitchell, A. et al. Maternal Western-style diet reduces social engagement and increases idiosyncratic behavior in Japanese macaque offspring. Brain. Behav. Immun. 105, 109–121 (2022).

Borge, T. C., Aase, H., Brantsæter, A. L. & Biele, G. The importance of maternal diet quality during pregnancy on cognitive and behavioural outcomes in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 7, e016777 (2017).

Gustafsson, H. C., Kuzava, S. E., Werner, E. A. & Monk, C. Maternal dietary fat intake during pregnancy is associated with infant temperament. Dev. Psychobiol. 58, 528–535 (2016).

Brunst, K. J. et al. Effects of prenatal social stress and maternal dietary fatty acid ratio on infant temperament: does race matter? Epidemiol. (Sunnyvale Calif) 4. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1165.1000167 (2014).

Lipton, L. R. et al. Associations among prenatal stress, maternal antioxidant intakes in pregnancy, and child temperament at age 30 months. J. Dev. Origins Health Disease. 8, 638–648 (2017).

Wolever, T. M., Jenkins, D., Jenkins, A. L. & Josse, R. G. The glycemic index: methodology and clinical implications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 54, 846–854 (1991).

Scholl, T. O., Chen, X., Khoo, C. S. & Lenders, C. The dietary glycemic index during pregnancy: influence on infant birth weight, fetal growth, and biomarkers of carbohydrate metabolism. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159, 467–474 (2004).

Hasbullah, F. Y. et al. Factors associated with dietary glycemic index and glycemic load in pregnant women and risk for gestational diabetes mellitus. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 71, 516–524 (2020).

Rao, P. S., Shashidhar, A. & Ashok, C. In utero fuel homeostasis: lessons for a clinician. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metabol. 17, 60 (2013).

Hu, F. B. et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 345, 790–797 (2001).

Willett, W., Manson, J. & Liu, S. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76, 274S–280S (2002).

Horan, M. K. et al. Maternal nutrition and glycaemic index during pregnancy impacts on offspring adiposity at 6 months of age—analysis from the ROLO randomised controlled trial. Nutrients 8, 7 (2016).

Maslova, E. et al. Maternal glycemic index and glycemic load in pregnancy and offspring metabolic health in childhood and adolescence—A cohort study of 68,471 mother–Offspring dyads from the Danish National birth cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 73, 1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0316-6 (2019).

Moses, R. G. et al. Effect of a low-glycemic-index diet during pregnancy on obstetric outcomes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 84, 807–812 (2006).

Okubo, H. et al. Maternal dietary glycemic index and glycemic load in early pregnancy are associated with offspring adiposity in childhood: the Southampton women’s survey. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 100, 676–683 (2014).

Alick, C. L. et al. Periconceptional maternal diet characterized by high glycemic loading is associated with offspring behavior in NEST. Nutrients 13, 3180 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Maternal dietary patterns and pregnancy outcome. Nutrients 8, 351 (2016).

Abu-Saad, K. & Fraser, D. Maternal nutrition and birth outcomes. Epidemiol. Rev. 32, 5–25 (2010).

Stifter, C. A., Willoughby, M. T. & Towe-Goodman, N. Agree or agree to disagree? Assessing the convergence between parents and observers on infant temperament. Infant Child. Development: Int. J. Res. Pract. 17, 407–426 (2008).

Gartstein, M. A. & Hancock, G. R. Temperamental growth in infancy: demographic, maternal symptom, and stress contributions to overarching and fine-grained dimensions. Merrill-Palmer Q. 65, 121–157 (2019).

Gustafsson, H. C. et al. Innovative methods for remote assessment of neurobehavioral development. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 52, 101015 (2021).

Wood, E. K. et al. The association between food desert severity, socioeconomic status, and metabolic state during pregnancy in a prospective longitudinal cohort. Sci. Rep. 13, 7197 (2023).

Conway, J. M., Ingwersen, L. M. & Moshfegh, A. J. Acurracy of dietary recal using the USDA 5-step multiple pass method in a multi-ethnic Populaiton: an observational validation study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 104(4), 595–603 (2003).

Foster-Powell, K., Holt, S. H. & Brand-Miller, J. C. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76, 5–56 (2002).

Flood, A. et al. Methodology for adding glycemic load values to the National Cancer Institute diet history questionnaire database. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 106, 393–402 (2006).

Olendzki, B. C. et al. Methodology for adding glycemic index and glycemic load values to 24-hour dietary recall database. Nutrition 22, 1087–1095 (2006).

Fields, D. A., Hunter, G. & Goran, M. I. Validation of the BOD POD with hydrostatic weighing: influence of body clothing. Int. J. Obes. 24, 200–205 (2000).

Fields, D. A., Higgins, P. B. & Radley, D. Air-displacement plethysmography: Here to stay. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metabolic Care. 8, 624–629 (2005).

Marshall, N. E. et al. Comparison of multiple methods to measure maternal fat mass in late gestation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 1055–1063. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.113464 (2016).

Van Raaij, J., Peek, M., Vermaat-Miedema, S. H., Schonk, C. M. & Hautvast, J. New equations for estimating body fat mass in pregnancy from body density or total body water. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 48, 24–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/48.1.24 (1988).

Wallace, T. M., Levy, J. C. & Matthews, D. R. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 27, 1487–1495 (2004).

Mesman, J., van IJzendoorn, M. H. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. The many faces of the Still-Face paradigm: A review and meta-analysis. Dev. Rev. 29, 120–162 (2009).

Tronick, E., Als, H., Adamson, L., Wise, S. & Brazelton, T. B. The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. J. Am. Acad. Child. Psychiatry. 17, 1–13 (1978).

Wagner, N. J. et al. Parenting and cortisol in infancy interactively predict conduct problems and callous–unemotional behaviors in childhood. Child Dev. 90, 279–297 (2019).

Hankin, B. L. et al. Understanding comorbidity among internalizing problems: integrating latent structural models of psychopathology and risk mechanisms. Dev. Psychopathol. 28, 987–1012 (2016).

Polanska, K. et al. Maternal stress during pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes of children during the first 2 years of life. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 53, 263–270 (2017).

Attali, E. & Yogev, Y. The impact of advanced maternal age on pregnancy outcome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 70, 2–9 (2021).

Cohen, A., Pieper, C. F., Brown, A. J. & Bastian, L. A. Number of children and risk of metabolic syndrome in women. J. Women’s Health. 15, 763–773 (2006).

Bentley-Lewis, R. et al. Effect of race/ethnicity on hypertension risk subsequent to gestational diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Cardiol. 113, 1364–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.411 (2014).

Feldman, R. et al. Maternal depression and anxiety across the postpartum year and infant social engagement, fear regulation, and stress reactivity. J. Am. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 48, 919–927 (2009).

Weissman, M. M. et al. Depressed mothers coming to primary care: maternal reports of problems with their children. J. Affect. Disord. 78, 93–100 (2004).

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T. & Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 24(4), 385–396 (1983).

World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr. Suppl. 450, 76–85 (2006).

Radloff, L. S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401 (1977).

Thompson, A. L. et al. Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite 53, 210–221 (2009).

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 130, e17–e37. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002159 (2017).

Graham, J. W. Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 60, 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530 (2009).

Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 21, 230–258 (1992).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Li, M., Francis, E., Hinkle, S. N., Ajjarapu, A. S. & Zhang, C. Preconception and prenatal nutrition and neurodevelopmental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 11, 1628 (2019).

Gustafsson, H. C. et al. Early development of negative and positive affect: implications for ADHD symptomatology across three birth cohorts. Dev. Psychopathol. 33, 1837–1848 (2021).

Jaimes, C. et al. In vivo characterization of emerging white matter microstructure in the fetal brain in the third trimester. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 41, 3177–3185 (2020).

Wilson, S. et al. Development of human white matter pathways in utero over the second and third trimester. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e2023598118 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Metabolic profiling of pregnancy: cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. BMC Med. 14, 1–14 (2016).

Ouyang, M., Dubois, J., Yu, Q., Mukherjee, P. & Huang, H. Delineation of early brain development from fetuses to infants with diffusion MRI and beyond. Neuroimage 185, 836–850 (2019).

Tau, G. Z. & Peterson, B. S. Normal development of brain circuits. Neuropsychopharmacology 35, 147–168 (2010).

Butte, N. F., Wong, W. W., Treuth, M. S., Ellis, K. J. & Smith, E. O. B. Energy requirements during pregnancy based on total energy expenditure and energy deposition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79, 1078–1087 (2004).

Cortés-Albornoz, M. C., García-Guáqueta, D. P., Velez-van-Meerbeke, A. & Talero-Gutiérrez, C. Maternal nutrition and neurodevelopment: A scoping review. Nutrients 13, 3530 (2021).

Caudill, M. A., Strupp, B. J., Muscalu, L., Nevins, J. E. & Canfield, R. L. Maternal choline supplementation during the third trimester of pregnancy improves infant information processing speed: a randomized, double-blind, controlled feeding study. FASEB J. 32, 2172 (2018).

Andescavage, N. N. et al. Complex trajectories of brain development in the healthy human fetus. Cereb. Cortex. 27, 5274–5283 (2017).

Wilcox, G. Insulin and insulin resistance. Clin. Biochemist Reviews. 26, 19 (2005).

Levitan, E. B. et al. Dietary glycemic index, dietary glycemic load, blood lipids, and C-reactive protein. Metabolism 57, 437–443 (2008).

Galgani, J., Aguirre, C. & Díaz, E. Acute effect of meal glycemic index and glycemic load on blood glucose and insulin responses in humans. Nutr. J. 5, 1–7 (2006).

Gawlińska, K. et al. Maternal dietary patterns are associated with susceptibility to a depressive-like phenotype in rat offspring. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 47, 100879 (2021).

Eyth, E. & Naik, R. Hemoglobin A1c. (2019).

Fabricatore, A. N., Ebbeling, C. B., Wadden, T. A. & Ludwig, D. S. Continuous glucose monitoring to assess the Ecologic validity of dietary glycemic index and glycemic load. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 94, 1519–1524 (2011).

McGowan, C. & McAuliffe, F. Maternal nutrient intakes and levels of energy underreporting during early pregnancy. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 906–913 (2012).

Nowicki, E. et al. Predictors of measurement error in energy intake during pregnancy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173, 560–568 (2011).

Küpers, L. K. et al. Maternal dietary glycemic index and glycemic load in pregnancy and offspring cord blood DNA methylation. Diabetes Care. 45, 1822–1832 (2022).

Kim, Y., Chen, J., Wirth, M. D., Shivappa, N. & Hebert, J. R. Lower dietary inflammatory index scores are associated with lower glycemic index scores among college students. Nutrients 10, 182 (2018).

Quagliaro, L. et al. Intermittent high glucose enhances apoptosis related to oxidative stress in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: the role of protein kinase C and NAD (P) H-oxidase activation. Diabetes 52, 2795–2804 (2003).

Wright, E. Jr, Scism-Bacon, J. & Glass, L. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: the role of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 60, 308–314 (2006).

Dawson, S. L. et al. Maternal prenatal gut microbiota composition predicts child behaviour. EBioMedicine 68, 103400 (2021).

Cao, Y. et al. Prenatal gut microbiota predicts temperament in offspring at 1–2 years. Biol. Res. Nurs. 26(4), 569–583 (2024).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Guilford, 2023).

Marshall, N. E. et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: lifelong consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226, 607–632 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (ELS and JTN, Grant Number: R01 MH117177), (JTN and ELS, Grant Number: R01 MH124824), (HCG, Grant Number: K01 MH120507). The project was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant Numbers: UL1 TR002369 and TL1 TR002371), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant Number: T32 AA007468), and by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (Grant Number: K12 AR084221). The funders played no role in the writing of this manuscript, or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. None of the data have been previously published. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Prenatal And Child Health (PEACH) study research staff that collected the data represented in the study. We would also like to express our appreciation to the participants in the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.W., H.C.G. and E.L.S.; methodology, E.K.W., J.C.A., J.T.N., H.C.G., and E.L.S.; formal analysis, E.K.W., H.C.G., and E.L.S.; resources, J.T.N., H.C.G., and E.L.S.; data curation, E.K.W., O.N., J.C.A., A.E., A.H., H.C.G., and E.L.S. writing—original draft preparation, E.K.W.; writing—review and editing, O.N., J.C.A., A.E., A.H., J.T.N., H.C.G., and E.L.S.; visualization, E.K.W.; supervision, E.L.S.; project administration, J.T.N., H.C.G., and E.L.S.; funding acquisition, E.K.W., J.T.N., H.C.G., and E.L.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wood, E.K., Nomura, O., Ablow, J.C. et al. Higher prenatal dietary glycemic index in the third trimester of pregnancy is associated with infant negative affect at 6 months. Sci Rep 15, 8357 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91886-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91886-0