Abstract

This research combines scaled model experiments with theoretical analysis to investigate the impact of underground utility tunnels (UUTs) on foundation bearing capacity and to examine the interaction between soil-rock composite strata and the stress-strain responses of the tunnel. The findings indicate that UUTs alter the foundation mechanism by reducing soil depth, streamlining the load transfer path, and causing stress to converge at the tunnel’s top. Additionally, the results reveal that the influence range of the tunnel on both sides is approximately 1.5 times its width and remains unaffected by the position of load application, the tunnel’s burial depth, or the width of the composite stratum. Moreover, when the width of the soil-rock composite stratum equals the width of the tunnel, the tunnel experiences a laterally flexural stress state. Within this specific stratum context, the central axis area of the tunnel roof and the connection with the side panels represent the core sensitive areas for crack initiation and propagation. In the failure scenario, the tunnel roof displays typical characteristics of fracture and depression, with the damage degree decreasing from the load center towards both ends. Meanwhile, the side panels do not exhibit characteristics of plastic deformation. This research provides a theoretical framework for the design, construction, and maintenance of UUTs, emphasizing its practical significance in engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As China’s urbanization process continues to advance, the scale of cities is experiencing a significant expansion, with urban population density, economic activity intensity, and resource flow demand reaching unprecedented levels. Urban infrastructure, as the critical support system for city operations, is of great significance, yet the rapid development has led to frequent failures of urban underground infrastructure (UUT) due to aging, limited design capacity, and planning that does not meet modern urban needs1,2. Once pipes break or clog, road excavation for repair is often unavoidable, which not only damages road structures and affects traffic but also poses a risk to the stability of nearby buildings and may trigger secondary disasters3,4. This contrasts sharply with the modern city’s stringent requirements for the efficient, convenient, and safe operation of infrastructure, severely limiting the effective performance of urban functions.

In soil-rock composite strata, the erosive action of water flow on the fissures of soluble rocks within the tunnel can lead to significant damage. When soil erosion occurs, the UUT structure is subjected to high stress and bending deformation, which severely compromises the safety of the UUT structure and the stability of the foundation5,6. In recent years, numerous scholars have focused on investigating the impact of soil-rock composite stratum on the mechanical response and failure modes of UUTs, accumulating a certain amount of research results in this field. Regarding the influence of composite stratum on the stability of UUTs, previous studies have revealed several key findings, as follows:

In terms of the influence of composite stratum characteristics, many studies have shown that heterogeneous soil layers and soft-hard inclined contact strata play a crucial role in the stability of tunnel structures. For example, according to the reports by Darli et al. and He et al., due to the uneven distribution of soil pressure in the heterogeneous area and the difference in acceleration response of the integrated tunnel structure within the area, the tunnel structure often remains under high stress conditions at the boundary of the heterogeneous soil layer, accompanied by significant bending deformation7,8. The study by Abate, Grasso et al. found that when tunnels pass through areas characterized by strong heterogeneity, the bending moments along the tunnel exhibit a significant non-uniform distribution, and significant bending moment peaks can be observed at points of discontinuity in soil stiffness, with the peak increasing with the increase in impedance ratio9. Additionally, Li et al. determined through research that the influence range of the soil section and the maximum settlement of the ground surface of shield tunneling are respectively greater than those of the rock Sect10. Regarding the impact of ground fissures, the situation where UUTs cross ground fissures has an undeniable effect on the performance of the structure. Studies by Deng et al., Yan et al., and Zhang et al. have pointed out that uneven settlements at the ends of ground fissures induce bending and twisting deformation in the structure11,12,13,14. Moreover, Hu et al. ’s research indicates that the shear compression on the fault plane during fault motion is the main cause of the longitudinal through-cracks in the tunnel lining when the tunnel crosses an active fault15. Specifically, when the fissure intersects the underground structure at right angles, the failure mode is characterized by extrusion; in the case of oblique intersection, torsional shear effects lead to twisting and tensile-extrusion failure modes16. However, the study by Li et al. showed that there was no significant correlation between the intersection angle and the vertical displacement or damage degree of UUTs17. Furthermore, Wu et al. revealed that with the increase in fault displacement, UUT structures experience overall deformation and joint expansion, leading to a significant decrease in tunnel waterproofing performance18. Overall, in the field of research related to soil-rock composite stratum, previous studies have mainly focused on the characteristics of composite stratum and the impact of ground fissures on the stress-strain response mechanism and stability of tunnel structures, while the exploration of the intrinsic mechanisms of the impact of underground integrated tunnel structures on bearing capacity in composite stratum is still insufficient, and the depth of research needs further expansion.

In terms of the impact of loads on the performance of UUTs, the study by Sharma et al. (2001) argued that while the enhancement of tunnel structure stiffness can reduce the displacement and deformation of the structure to some extent, the bending moments of the structure will significantly increase at the same time14. The study by Rakitin and Xu focused on heavy truck loads, finding that even when the soil cover depth is 4 m, the bending moments induced by such loads are still far greater than those induced by the self-weight of the overlying soil19. Malhotra et al. found that the presence of buried pipelines has a negligible impact on the performance of foundations when the depth is below a certain critical value20. Additionally, the study by Qiu et al. innovatively proposed the concept of a staggered assembly structure of composite stratum and conducted prototype bending tests, with the results showing that the failure of the structure originated from the cracking of the stiffer regions, leading to a redistribution of the structure’s stiffness21. In the academic research of the past, many scholars have conducted extensive and in-depth explorations around the impact of load location, size, and soil cover depth on the stress response of UUT structures, and have achieved corresponding. However, based on the current research status, in the specific geological condition of soil-rock composite stratum, when structures are subjected to loads, research on the intrinsic mechanisms of the impact of UUTs on stress-strain responses and the limit failure modes under complex conditions is still relatively scarce, which undoubtedly limits the perfection of the theoretical system in this field and the efficient implementation of engineering practices.

In summary, prior research has primarily concentrated on the intrinsic characteristics of composite strata, the stress-strain response mechanisms of tunnel structures influenced by ground fissures, and the resultant impact on structural stability. Nevertheless, the mechanisms through which underground integrated culverts influence the bearing capacity of composite strata remain poorly understood, necessitating further investigation to elaborate on this aspect. Furthermore, a notable insufficiency exists in the current research concerning the effects of variations in factors such as soil layer widths within composite strata on the bearing capacity and response mechanisms of UUTs.

This study takes the UUT project in Liuzhou City as an example, uses the DJM electric-hydraulic servo loading system to conduct experimental testing on UUT scaled models under different working conditions, and performs corresponding numerical simulations to reinforce experimental results, aiming to investigate the impact of UUT on the ultimate bearing capacity of the foundation, with a particular focus on the effects of the deformation, mechanical characteristics evolution, and limit failure modes of UUT structures in karst areas due to different width red clay layers and weathered limestone composing the soil-rock composite strata, providing critical reference for the design and construction of UUT.

Methods

Model design of indoor experiments

This research is anchored in the UUT project in Liuzhou City, a project distinguished by its unique engineering characteristics and geological conditions. Notably, the project’s route necessitates traversing beneath a railway, thereby significantly complicating and challenging the project’s implementation. Geologically, the strata beneath the elevation of the UUT’s bottom surface exhibit a diverse composition, consisting primarily of hard plastic red clay, strongly weathered dolomite, and moderately weathered dolomite. This heterogeneity endows the affected section with a composite soil-rock foundation. Based on relevant engineering judgment standards, the aforementioned stratum conditions can serve as the foundation bearing layer for the project’s standard sections or nodes, offering a certain level of bearing and supporting capacity to the structure. The intricate and specialized geological conditions form the real-world backdrop that has spurred the project’s related research and experiments, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

This experiment is grounded in the UUT project in Liuzhou City, focusing on scaled model tests. Wu et al. study revealed that the deformation laws, spatial distribution of failure cracks, and failure modes of scaled models with varying scaling ratios are largely consistent in critical aspects18. Furthermore, research indicates that to mitigate boundary effects on test outcomes, the side length of the model box should be at least three times the side length of the UUT22,23,24. The model box used in this indoor test measures 1500 mm×1000 mm×1300 mm (L×W×H). The prototype single-chamber UUT’s cross-sectional dimensions are 5,200 mm×6,700 mm (W×H), with a wall thickness of 400 mm. Consequently, the chosen model scaling ratio is 1:20, resulting in a scaled model cross-sectional size of 260 mm×335 mm (W×H) and a wall thickness of 20 mm.

The UUT model material was a custom microparticle concrete25,26. This material possesses mechanical properties akin to those of concrete used in real engineering projects, allowing the scaled model to accurately reflect the mechanical characteristics of the actual UUT structure, particularly in terms of stress responses. As a result, the test results derived from this model are more valuable for reference. The material parameters are detailed in Table 1. Additionally, the model similarity ratio was designed in accordance with similarity theory, as presented in Table 2.

Note

Generated using DJI Terra 2.1.2 (Official website: https://www.dji.com/cn).

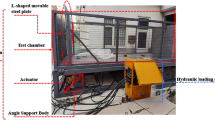

Methods of model tests

According to the design specifications and engineering requirements, the foundation bearing stratum for the UUT project is designed to utilize hard plastic red clay, strongly weathered dolomite, or medium weathered dolomite as the primary bearing layer. These materials exhibit sufficient mechanical strength to ensure structural stability and load-bearing capacity, thereby eliminating the need for replacement measures. However, if the actual geological conditions indicate the presence of residual soil, plain fill soil, soft plastic red clay, or other soil layers with inadequate mechanical properties, appropriate ground improvement measures will be implemented to enhance the foundation’s stability and meet the required bearing capacity standards. In the indoor model test, two independent and complete concrete piers were constructed to simulate the rock, with red clay from the engineering site filling the space between the piers and being compacted. This soil-rock composite stratum with varying soil layer widths was simulated by adjusting the relative position of the two concrete piers. A drainage sand cushion (1 cm thick) was then placed above the composite stratum, followed by the placement of the UUT in the designated position within the layered backfill soil. The thickness of the soil layer over the pipe corridor was 225 mm, and a gravel layer (50 mm thick) was laid on top of the soil. The test setup is depicted in Figs. 2 and 3. To account for the model’s symmetry, the midspan section and longitudinal axis of the utility tunnel were used as the symmetry axis for instrument placement. The earth pressure cell was positioned on one side of the UUT, and strain gauges were uniformly mounted at the midspan, as illustrated in Fig. 2(b). To investigate the UUT’s impact on foundation bearing capacity and the composite stratum’s influence on the UUT ‘s mechanical properties, two variables were considered: the utility tunnel and the width of the soil layer. The test conditions are detailed in Tables 3, and the Composite stratum is shown in Fig. 4. A pretest was conducted in accordance with the standard geotechnical test method before the formal test. During this pretest, the UUT was placed on the rock foundation as a sample. The results indicated that the model’s ultimate bearing capacity was 100 kN, and the loading levels were graded at 1/10 increments of the ultimate bearing capacity for the formal test.

Establishment and verification of the ABAQUS numerical model

To investigate the intrinsic mechanism by which the length of soil layers in an Soil-rock composite stratum influences the mechanical response of a comprehensive pipeline gallery, this study builds upon previous indoor model tests and employs the ABAQUS2024 (Abaqus Learning Edition, https://www.3ds.com/edu/education/students/solutions/abaqus-le/) finite element software to create a corresponding three-dimensional model. Care was taken during the construction of the numerical model to maintain consistency with the dimensions of the indoor model test, with the goal of accurately replicating the actual testing scenario to ensure the reliability of subsequent simulation analyses. In the numerical simulation phase, the soil is modeled as a uniform and isotropic medium, and the Mohr-Coulomb model is selected to describe its mechanical behavior. The model’s boundary conditions are defined as follows: the top surface is designated as a free surface, enabling free deformation; normal constraints are imposed on the four sides (front, back, left, and right) to limit displacement in their respective directions; and the bottom surface is fixed to maintain its position. The contact between the pipeline gallery and the soil is defined using the penalty contact method, with a friction coefficient of 0.35 between the soil and the UUT surface to accurately represent their interaction. The model is meshed using the C3D8R element to achieve a balance between calculation accuracy and efficiency. The three-dimensional model of the UUT is presented in Fig. 5, and the material parameters for the numerical model are detailed in Table 4.

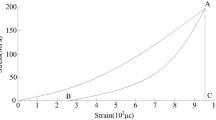

Figure 6 presents the load-settlement curves for the indoor model test and finite element simulation conducted under Condition 1. Comparative analysis reveals a strong correlation between the load-settlement curve produced by the finite element model and the results from the indoor model test. This observation underscores the robust effectiveness of the developed finite element numerical model, which accurately captures the mechanical behavior of the UUT during the indoor test. This capability offers a reliable foundation for further investigating the mechanical properties of the UUT in Soil-rock composite stratum.

Theoretical analysis of the model

The force analysis of the UUT is based on the beam model of the elastic foundation and Winkler’s hypothesis. In this analysis, the rock within the soil-rock composite stratum is assumed to behave as a rigid body, while the tunnel is modeled as an elastic-plastic body. The soil is represented as a soil spring with a specific stiffness. Furthermore, the tunnel is treated as an infinite underground structure. In this experiment, the vertical and horizontal displacements of the tunnel are constrained by several factors, including friction, soil gravity, and the dead weight of the tunnel. Thus, the loading structure of the UUT can be simplified as a multispan (unequal spans) continuous beam structure, as shown in Fig. 7. The distribution of the bending moment of the UUT section in the Composite stratum is described as follows. The maximum bending moment of the tunnel section is located in the middle of the span, and the maximum shearing force is located at the junction between the rock and soil. In addition, the shear force and midspan bending moment at the junction between the rock and soil increase gradually with increasing soil layer width in the Composite stratum. Taking the UUT and composite stratum as a whole, the difference in the structure and stiffness of the tunnel in the foundation will lead to the difference between the settlement rate and final settlement amount of the soil above the tunnel and those of the soil on both sides of the tunnel. In addition, the bending normal stress of the top and bottom plate of the UUT is transmitted through the shear surface at the joints of the top, bottom plate and web plate. Combined with the analysis of the model stress and bending moment diagrams, it can be seen that the increase of the bending moment and displacement of the UUT will lead to faster cracking of the bottom plate, as shown in Fig. 7. After cracking of the tunnel’s bottom plate, the structural stiffness will decrease rapidly, and the deflection of the tunnel (i.e., the macro performance) will increase further27. Combined with the shear deformation theory of concrete beams, the relationship between the maximum deflection ω of the UUT and the full section bending and main body shear deformation is as expressed as follows.

Based on the classical theory of bimodal displacement the equilibrium equation at the UUT section can be expressed as follows.

Here, ω is the deflection of the center line of the section, θ is the bending angle of the shear deformation of the section, φ is the average shear strain, D is the bending stiffness, and C is the shear strength.

In addition, in the theoretical analysis of the model, the UUT can be considered a rectangular cross-section beam with a wall of equal thickness. In the infinite point of the UUT, it is believed that the section cannot be warped freely and is in a constrained torsion state when there is a strong transverse diaphragm at the end of the section. In this case, the normal stress generated by the warping of the UUT section further worsens the deformation of the tunnel, as shown in Fig. 8. In summary, the macro effects of the composite strata on the foundation are shown as a decrease in foundation bearing capacity and an increase in deflection of the UUT. However, the ultimate bearing capacity of the foundation, the stress and deformation of an UUT and the ultimate failure mode of the structure need to be further studied quantitatively through tests.

Results

Foundation bearing capacity analysis

Figure 9 illustrates the P-S curve for the foundation under static loading. The curve delineates three distinct stages of stress and deformation: the elastic compaction stage, the elastoplastic stage, and the failure stage. P0 denotes the proportional limit, while Pµ represents the ultimate load. Under the test conditions presented, P0 is 40 kN and Pµ is 80 kN, as depicted in Fig. 9. A detailed analysis of the P-Scurve and the earth pressure distribution diagram reveals that the UUT has a pronounced effect on the foundation’s bearing capacity. It enhances the foundation’s bearing capacity and significantly reduces the compression settlement rate, findings that align with Wang’s research27. Observing the P-S curve further, it becomes evident that when the load exceeds 30 kN, the slopes of the P-S curves with and without the UUT exhibit a distinct divergence. This trend intensifies as the load increases, with a notable separation at 40 kN, where the foundation settlement is reduced by 17% due to the presence of the utility tunnel. At a load of 80 kN, the reduction in foundation settlement is even more substantial, reaching 29.3%.

The vertical earth pressure in the direction of the vertical tunnel provides an intuitive demonstration of the principle by which the utility tunnel alters the foundation bearing mechanism, as depicted in Fig. 10. The soil pressure distribution illustrates that the internal stress distribution of the foundation changes before and after the tunnel’s presence, with a significant increase in load at the tunnel roof and a decrease in earth pressure at the soil positions on both sides of the tunnel compared to the condition without the tunnel. At a load of 40 kN, the earth pressure at the tunnel roof increases by 57.04 kPa relative to the no-tunnel condition. The earth pressure on both sides of the tunnel decreases by 16.16 kPa, and at the h/2 position of the tunnel, it decreases by 12.5 kPa. Notably, an interesting phenomenon occurs at the h/2 plane of the tunnel under working conditions. The earth pressure at the edge of the tunnel’s side plate is the minimum, and it gradually increases with increasing distance from the side plate, eventually stabilizing.

Earth pressure analysis

In this study, the analysis of data from various test conditions revealed several significant experimental phenomena. Notably, the peak pressure at the roof position under different conditions follows a specific order, from highest to lowest: rock foundation with UUT > Composite stratum 2 > Composite stratum 1 > rock foundation without UUT, as depicted in Fig. 11. Similarly, the peak pressure at the bottom plate exhibits a corresponding sequence: rock foundation without UUT > rock foundation with UUT > Composite stratum 1 > Composite stratum 2, as illustrated in Fig. 12. The variation in peak pressures between the roof and bottom plates across different conditions is closely tied to the stratigraphic conditions and the presence of the UUT. For instance, the inherent bearing characteristics of the rock foundation, combined with the influence of the UUT, lead to a change in the peak roof pressure when the UUT is present. Additionally, the distinct structural compositions of the Composite stratum further modulate the pressure response, resulting in the observed pressure magnitude order.

Further analysis indicates that under the conditions of Composite stratum 1 and 2, the vertical pressure distribution on the UUT bottom plate follows a distinctive pattern. Notably, as the distance from the load center increases, the pressure initially rises before gradually decreasing, with the peak pressure occurring precisely at the interface between the UUT and the rock, suggesting stress concentration at that point. Specifically, when the load is 80kN, the pressure peak in Composite stratum 1 is 76.82 kPa, and in Composite stratum 2, it is 73.33 kPa, which underscores the variations in stress concentration and pressure distribution across different Composite stratum scenarios, as depicted in Fig. 12. Additionally, the soil pressure on both the top and bottom plates of the gallery stabilizes at a distance of 257 mm from the UUT center. This stability is not coincidental. The analysis of vertical soil pressure patterns suggests that the UUT’s influence extends approximately 1.5 times the width of the UUT, and it is important to note that this influence range is independent of the load magnitude or the nature of the Composite stratum.

Moreover, the UUT’s presence significantly influences soil pressure changes at the roof, characterized by an increase in peak pressure and a shift in the rate of pressure decrease along the UUT’s length to a linear decline before stabilization. To clarify this, at an 80kN load, the peak pressures at the gallery’s roof are 173.49 kPa with the UUT and 279.90 kPa without it. At 130 mm from the loading plate center, the pressures are 127.9 kPa with the UUT and 172.17 kPa without it, and at 260 mm, they are 49.82 kPa with the UUT and 81.22 kPa without it. Similarly, at an 80kN load, the UUT’s presence results in the soil pressure reduction rate curves at the gallery’s bottom plate showing an approximately linear decrease along the UUT’s length, with slopes of −76.38 and − 8.83, as depicted in Fig. 12. This sequence of data variations underscores the UUT’s influence on soil pressure changes across the gallery and offers a critical foundation for our comprehensive investigation of the mechanical behavior within the entire testing system.

Structural deformation analysis of UUT

The total strain of the UUT exhibits a linearly proportional increase with changes in load, as visually depicted in Fig. 13(a). The figure illustrates that data points corresponding to each working condition are closely aligned with their respective fitted lines, accurately reflecting the linear relationship. At a total strain of 20 mm, the rock foundation condition exhibits a load of 62.50 kN, while the composite stratum 1 and 2 conditions correspond to loads of 38.46 kN and 54.05 kN, respectively28. This suggests that the width of the soil layer in composite strata significantly influences the UUT’s foundation bearing capacity during operation. Consequently, in the context of engineering geological safety risk assessment, the soil layer width is a critical factor that warrants careful consideration. Further analysis of Fig. 13(a) reveals that the slope of the curve-fitting line corresponds to the change in total strain of the UUT under equivalent load increments across different working conditions. Specifically, the slope of the fitted line for the composite stratum 1 condition (0.52) is notably greater than that for the rock foundation (0.32) and composite stratum 2 (0.37), suggesting a higher susceptibility to deformation in the UUT structure under the composite stratum 1 condition.

A comparative analysis of the hoop strain in the UUT’s central cross-section within both rock foundation and composite strata allows for a more profound examination of the influence of composite strata on UUT strain. To mitigate the risk of sudden changes due to the UUT exceeding controlled variables during testing, the hoop strain under a load of 38.46 kN was investigated, with details provided in Fig. 13(b). The figure reveals that while the deformation patterns of the UUT’s top, bottom, and side plates are broadly consistent across different working conditions, there are marked differences in the extent of deformation for the top and bottom plates. The ranking of total strain and top plate strain of the UUT, from highest to lowest across conditions, is: composite stratum 1 > composite stratum 2 > rock foundation. Specifically, the peak top plate strain is 2,300 μm in the composite stratum 1, 2,060 μm in the composite stratum 2, and 1,930 μm in the rock foundation. Similarly, the order of bottom plate strain is: composite stratum 2 > composite stratum 1 > rock foundation. These findings suggest that managing the top plate strain is crucial for controlling the UUT’s overall structural deformation. Consequently, this factor must be thoroughly considered during the UUT’s structural design and the development of auxiliary protective measures. The strain distribution depicted in Fig. 13(b) offers critical design insights, particularly when designing the top plate structure, necessitating reference to the figure’s top plate strain data to ensure structural integrity and prevent failure due to excessive top plate strain.

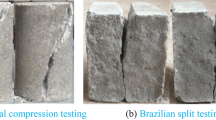

Ultimate failure mode of UUT structure

The crack distribution map for the indoor model UUT reveals a uniform distribution along the vertical axis of the UUT’s top and bottom plates within the range of −0.3 W to 0.3 W, as well as at the interface between the top and side plates, as depicted in Figs. 14, 15, 16 and 17. These cracks extend along the length of the UUT, exhibiting a pattern of increased width in the middle and reduced width at the ends. Nonetheless, the UUT’s crack distribution and cracking extent under the three distinct working conditions display unique attributes. For instance, under rock foundation conditions, the widest crack is situated along the central axis of the top and bottom plates, with a maximum difference in crack width between the plates of only 0.15 mm. This suggests that the tensile stress difference between the plates is relatively minor throughout the UUT’s overall stress process, as illustrated in Fig. 14. The rock foundation facilitates the maximum transmission of compressive stress through the side plates and the lateral support function of the top and bottom plates. For the composite stratum 2 condition, the UUT’s crack distribution characteristics are akin to those observed under rock foundation conditions. However, the maximum crack width at the vertical axis of the UUT’s top plate reaches 2.3 mm, while the bottom plate’s maximum crack width is 1.0 mm, accompanied by a notable increase in the gap at the junction between the top and side plates, as shown in Fig. 16. In the Composite stratum 1, the maximum crack width at the connection between the top and side plates is 2.2 mm, with a phenomenon of transverse cracks extending towards the side plate, as depicted in Fig. 15.

Upon reaching the UUT’s ultimate load, the top plate exhibited a final failure mode characterized by an inverted parabolic shape, fracturing into multiple pieces and separating horizontally from the side plates. In the longitudinal direction, the degree of damage to the top plate decreased gradually from the load center to the ends, with some adhesion observed between the ends of the top plate and the side plates. Comparison of the UUT’s side plate spacing before and after ultimate failure revealed no significant change, indicating that the side plates did not undergo plastic deformation towards the interior of the UUT under these conditions, as shown in Fig. 17.

Analysis of numerical simulation results

To facilitate a more intuitive understanding of the impact of the UUT on the pressure distribution within the foundation soil, this study extracted the vertical stress cloud map for the tunnel’s mid-span section under a load of 40 kN, as depicted in Fig. 18. Figure 18(a) illustrates a pronounced uneven settlement between the soil above the tunnel and the adjacent soil, with the settlement difference diminishing as the distance from the tunnel increases. Figure 18(b) further reveals a significant soil arching effect at the tunnel’s top plate, with a notably higher load concentration at the interface between the top plate and the side plates compared to the centerline of the top plate.

Analysis of the Mises stress cloud maps presented in Fig. 19(a) indicates that under rock foundation conditions, the stress on the side plates of the tunnel is uniformly distributed, with the peak stress reaching 1.17 MPa. In contrast, under Soil-rock composite stratum conditions, the tunnel’s bottom plate at the rock-soil interface exhibits varying degrees of stress concentration. In particular, in the case of Composite stratum 1, the peak stress of the tunnel structure can reach 1.78 MPa, while in Composite stratum 2, it is 2.57 MPa. Notably, in Composite stratum 1, the top plate also sustains a significant concentrated stress, ranking second only to the bottom plate at 1.61 MPa, as illustrated in Fig. 19(b) and (c). This suggests that the stress distribution in Composite stratum 1 is relatively uneven from a macro perspective. Comparative analysis of the structural stress profiles between Composite stratum 1 and 2 reveals that both exhibit peak stresses at the bottom plate, with stress levels decreasing towards the middle of the top plate. The green low-stress areas extend and connect, forming an arch-like pattern. Furthermore, in Composite stratum 1, the constraint forces at the ends of the structure are significantly greater than those in Composite stratum 2 and the rock foundation, with stress values at the tunnel ends reaching 225.7 kPa.

Discussion

In the context of the ongoing development of urban infrastructure, the use of UUTs has expanded significantly. Nevertheless, the intricate interactions between UUTs and their foundations have emerged as a critical scientific issue that necessitates further investigation. Key questions include the impact of UUTs on foundation bearing capacity, their influence on load transfer paths and stress-strain state changes across various strata (particularly composite strata), and how these effects reciprocally impact engineering design and structural stability. These aspects are in need of more comprehensive research. In light of these considerations, this study utilizes meticulously designed scaled model tests, complemented by theoretical analysis and ABAQUS numerical simulations, to explore the soil-rock composite strata as a focal point. It aims to delve into the effects of UUTs on foundation bearing capacity, the role of composite strata in the stress-strain response of UUTs, and the impact of the length of the soil-rock composite strata on UUT structure and foundation bearing capacity. The objective is to accurately elucidate the complex interaction dynamics, thereby offering a scientific foundation and practical guidance for the design, construction, and maintenance of UUT.

The impact of UUTs on foundation bearing capacity is a multifaceted process involving the interplay of various factors. The reduction in soil layer depth, the decrease in the depth of stress diffusion, and the simplification of the load transfer path collectively modify the foundation’s mechanical response under loading. These modifications not only augment the foundation’s bearing capacity but also result in a substantial alteration of the stress distribution pattern. Notably, at the UUT’s top plate, stress concentration is marked, characterized by a substantial increase in vertical soil pressure at the tunnel’s crown and an accelerated rate of stress transfer to the foundation, significantly affecting the overall stability of the foundation-UUT system, as depicted in Figs. 11 and 19(b).

Under rock foundation conditions, the load transfer path of the UUT can elucidate the reasons behind its influence on foundation bearing capacity. The presence of the UUT introduces an additional load transfer stage, necessitating that the load traverse the UUT before reaching the rock layer, indicating that the UUT serves as a transmission medium in the load distribution process. This alteration in the load transfer sequence significantly affects the accumulation and dissipation of stresses within the soil-rock system, as illustrated in Fig. 18(a). The UUT’s influence on the load transfer path is particularly evident by an increase in the rate of vertical soil pressure decrease within a 257 mm radius from the UUT’s center (approximately 1.5 times the tunnel’s width), an effect that is independent of the load magnitude and the specific conditions of the Composite stratum. Furthermore, the UUT affects the uniformity of the vertical pressure distribution at the bottom plate, with the slopes of the vertical pressure fitting curves before and after the tunnel’s presence being − 76.38 and − 8.83, respectively, as shown in Fig. 12. These observations indicate that the UUT plays a pivotal role in the distribution of loads within the strata, thereby influencing the stability and performance of the entire foundation-UUT structure.

Drawing on the theory of additional stress, the soil arching effect provides further insight into the stress redistribution and load transfer mechanisms within the foundation. The combination of the vertical settlement cloud map in Fig. 18(a) and the vertical stress cloud map in Fig. 18(b) explains the stable rate of decrease in vertical soil pressure beyond the 1.5 times the UUT width. Initially, the tunnel induces significant differential soil settlement, intensifying stress concentration at the crown and slowing the rate of load reduction in depth and horizontally. Secondly, the soil arching effect redistributes the load to the soil on either side of the tunnel, reducing the load on the soil at the edge of the side plates and thus altering the soil settlement pattern. Thirdly, the pronounced soil arching effect near the tunnel leads to uneven soil settlement, whereas the effect diminishes and the differential settlement decreases as one moves away from the tunnel. Compared with the research findings of Yang et al. and Wang et al., their study only pointed out that during the process of soil settlement and deformation, the relative displacement of the UUT and the shearing effect on both sides of the UUT might have a certain impact29,30. However, our research has gone a step further. We have conducted more in-depth explorations on the specific mechanism of UUTs and their interactions with the foundation under different stratum conditions, thus providing a more comprehensive and thorough understanding of this phenomenon.

Theoretical analysis reveals that as the width of the soil layer within the composite stratum increases from zero to twice the width of the UUT, the internal structure of the UUT undergoes a series of distinct stress state transitions, including pure shear, lateral bending, and pure bending. Specifically, under the conditions of the composite stratum 1, the UUT structure exhibits a stress state that is more akin to lateral bending, which impairs the full utilization of the reinforcement’s tensile capacity, resulting in a less favorable mechanical condition. The strain conditions observed in the UUT structure under various loads, as depicted in Fig. 10, and the characteristics of the ultimate failure crack propagation, as shown in Fig. 15, provide further validation for this analysis. Concurrently, numerical simulations indicate that the central low-stress regions of the Composite stratum 1 and 2 extend and connect to form an arch-like structure, with stress peaks localized at the bottom plate, as illustrated in Fig. 19. Notably, the top plate of the UUT in the Composite stratum 1 also sustains significant concentrated stress, and the constraint forces at both ends of the structure are substantially greater than those in the Composite stratum 2 and rock foundation. This aligns with the theoretical analysis of stress state changes within the composite stratum and suggests that the UUT structures of the uneven foundations 1 and 2 are subject to different stress state stages.

As the soil layer width in the composite stratum expands to twice the UUT width, its internal structure sequentially experiences the aforementioned stress state transitions. Understanding the underlying causes of these transitions is crucial for the present study. The analysis indicates that in the Composite stratum 1, stress concentration at the interface between rock and soil layers leads to a substantial shear stress at the structure’s base. External loads or deformation incoordination result in high stress at the structure’s top due to overall deformation, leading the stress state of the Composite stratum 1 to favor lateral bending. In the Composite stratum 2, the green low-stress area extends and connects to form an arch-like structure, with no significant stress concentration observed at the top plate. This suggests a stress state that is transitioning towards lateral bending, as depicted in Fig. 19(c).

Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates that side walls are the primary components for vertical load transfer, while the top and bottom plates contribute to load transfer by leveraging the compressive strength of concrete and the tensile strength of reinforcement. This provides valuable insights into the structural mechanics of the UUT. The synergistic action of these components is essential for maintaining the lateral support of the UUT structure. In the UUT’s ultimate failure state, the spacing between the side walls remains relatively unchanged before and after failure, indicating that the UUT structure’s stiffness and the support from surrounding dense soil are effective, as shown in Fig. 17(a). This finding is significant for evaluating the UUT’s structural integrity under extreme load conditions and can guide the design of reinforcement measures to enhance the UUT’s resistance to failure.

The research outcomes underscore the substantial impact of the soil layer width in the Composite stratum on the UUT’s internal stress distribution. This highlights the importance of considering the interaction between the UUT structure and the soil during design. As the soil layer width increases, the UUT structure transitions from pure shear, lateral bending, and pure bending states, demonstrating the UUT’s adaptability to varying soil conditions and its enhanced mechanical performance. The dynamic behavior of the UUT within the composite stratum underscores the necessity of a comprehensive understanding of soil-tunnel interaction for optimizing design and ensuring the UUT’s long-term performance. Recognizing these stress state changes aids in predicting potential failure modes and implementing preventive measures during construction and operation phases.

Within the confines of this indoor model experiment framework, the crack distribution of the UUT exhibits a consistent pattern, predominantly localized within the interval of −0.3 W to 0.3 W. These cracks are predominantly observed along the vertical axis of the UUT’s top and bottom plates and at the interface between the top and side plates, extending along the UUT’s length. Figures 14 and 15, and 16provide visual representation. The crack distribution zones observed in this study are consistent with the prone-to-cracking zones reported in the findings of Wang et al., and this consistency is primarily attributed to the geometric configuration of the UUT structure and the distribution characteristics of the overlying load31,32. Building on this foundation, this research explores the influence of Composite stratum on the crack propagation features of culvert structures. Notably, the crack width demonstrates a trend of being wider in the middle and narrower at the ends along the UUT’s longitudinal axis. Additionally, the degree of crack development on the top plate is notably greater than on the bottom plate. From a structural mechanics standpoint, this distribution pattern suggests significant variations in stress conditions across different regions of the UUT under load. The top plate, as the primary structural component bearing the upper load and external forces, experiences a more intricate stress process and a more pronounced stress concentration, leading to more extensive crack formation and propagation. This observation underscores the UUT’s uneven load transfer and force response characteristics, offering a foundation for a comprehensive investigation into its mechanical behavior. Conversely, experimental results under composite stratum 2 conditions, while sharing some similarities with rock foundation conditions in terms of crack distribution, also reveal notable disparities, Fig. 15 illustrates these differences. Notably, the maximum crack width at the vertical axis of the top plate reaches 2.3 mm, whereas the maximum crack width at the bottom plate is only 1.0 mm. Moreover, there is a discernible trend of increased gap at the junction between the top and side plates. This suggests that the unique stratigraphic characteristics of composite stratum 2 result in the top plate being in a less favorable stress state when subjected to loads, thereby increasing its susceptibility to significant cracking. Concurrently, the connection areas between the side plate and the top plate are also more prominently affected. This indicates that composite stratum 2 is less effective in stress coordination compared to the rock foundation, exacerbating localized stress imbalances and negatively impacting structural integrity.

In the context of Composite stratum 1, the UUT exhibits distinct features, such as a maximum crack width of 2.2 mm at the connection between the top and side plates, cracks extending from the center to both side plates, and longitudinal connections at the bottom plate and side plate junctions, as depicted in Fig. 15. These observations confirm that under the extreme conditions of composite stratum 1, the UUT’s top, bottom, and side plates are vulnerable to damage under load. This suggests that the unique geological conditions of composite stratum 1 render the connection areas as weak points within the UUT structure. During load transfer, stress is challenging to disperse and coordinate effectively in these areas. Upon exposure to a large load, the connection areas are the first to exceed their bearing limits, resulting in structural damage and posing a significant threat to the overall stability of the UUT. This aligns with the patterns observed in Fig. 19(b) of the numerical simulation. This underscores the importance of reinforcing the design and optimizing the mechanical properties of the structural connection areas under the conditions of composite stratum 1, which is of considerable engineering importance for ensuring the UUT’s safe operation under complex geological conditions.

Upon reaching the ultimate load state, the top plate exhibits an ultimate failure shape characterized by an inverted parabola, fracturing into multiple pieces and separating horizontally from the side plates. Observing along the longitudinal axis, the degree of damage decreases gradually from the load center to the ends, with some adhesion observed between the top and side plates at the ends. Figure 17 illustrates this. This distinctive failure shape vividly illustrates the complex stress failure process and stress release mechanism of the top plate under the ultimate load. Concurrently, a comparison of the spacing between the UUT’s two sides reveals no significant change before and after the ultimate failure. This indicates that under the ultimate failure conditions, the side plate does not undergo significant plastic deformation towards the interior of the UUT. This suggests that the side plate maintains a degree of structural stability under the ultimate load, yet also implies that the top plate bears the majority of the destructive energy during the ultimate stress phase. This further highlights the differentiated response mechanisms of the UUT’s various components under ultimate stress conditions and clearly identifies the structure’s weak points under such conditions, providing substantial experimental evidence for in-depth research into the UUT’s ultimate bearing capacity and failure modes.

The analysis of the UUT’s impact on foundation bearing capacity, stress state variations, and load transfer mechanisms highlights several critical considerations for engineering design. Initially, engineers must account for the influence range of the UUT and its effects on the foundation when designing the UUT under similar geological conditions. This may necessitate the implementation of suitable foundation reinforcement measures within the affected area to guarantee that the bearing capacity aligns with design specifications. Additionally, the stress state changes of the UUT structure within various strata, particularly composite strata, merit attention. Adapting the reinforcement layout and material selection to anticipated stress conditions can enhance the UUT’s structural performance and longevity.

Moreover, the role of different structural components in load transfer and the stability offered by backfill soil necessitates the optimization of the design for side plates, top plate, and bottom plate. Enhancing their synergy and interaction can bolster the UUT’s overall structural integrity. For instance, ensuring adequate connections and reinforcement between side plates and other components can facilitate load distribution and mitigate potential damage.

Conclusion

This study examines the impact of the UUT on the foundation’s bearing capacity, the role of composite strata in the stress-strain response of the UUT, and the influence of the length of the rock-composite strata on the structure’s ultimate failure mode. The following key conclusions are presented:

(1) The mechanism by which the UUT influences the foundation’s bearing capacity is a complex interplay of various factors. The reduction in soil depth, the decrease in stress diffusion depth, and the simplification of the load transfer path collectively modify the foundation’s mechanical behavior. This not only enhances the foundation’s bearing capacity but also results in a significant shift in the stress distribution pattern. Notably, the influence range of the UUT is independent of the load magnitude and the width of the soil layer, and soil pressure stabilizes at a distance of 1.5 times the UUT’s width from its center.

(2) Alterations in the soil layer width can impact the load transfer path, thereby affecting the foundation’s bearing capacity and the overall stability of the structure. When the width of the soil in the composite strata equals the width of the UUT structure, the UUT’s bearing capacity is at its minimum. Under these conditions, the UUT structure bends laterally under the combined action of shear and bending forces. It is important to note that during the loading process, the composite strata do not alter the overall trend of the UUT’s strain. However, the impact is primarily observed in the deformation of the top and bottom plates, with the deformation of the top plate being the most critical factor influencing the UUT’s overall deformation.

(3) Within the composite strata, the central axis of the UUT’s top plate and the junction between the top and side plates are crucial in the formation and propagation of cracks. Specifically, cracks are prone to develop from the central axis of the top plate towards the side plate. In the ultimate failure state, the UUT assumes a shape characterized by an inverted parabolic indentation, with the vertical axis of the top plate serving as the primary fracture surface. Concurrently, the top plate breaks horizontally into multiple segments, separating from the side plate. Despite the complex failure conditions, the side plate, due to its inherent stiffness and the effective support from the surrounding dense soil, does not exhibit plastic deformation towards the UUT’s interior or exterior.

Data availability

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.

References

Qian, Q., Chen, X. & Situation Problems and countermeasures of utility tunnel’ development in China and abroad. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 02, 191–194 (2007).

Canto, P. J. & Curiel, E. J. Assessing governance issues of urban utility tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 33, 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2012.08.007 (2013).

Valdenebro, J. V. & Gimena, F. N. Urban utility tunnels as a long-term solution for the sustainable revitalization of historic centres: the case study of Pamplona-Spain. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 81, 228–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2018.07.024 (2018).

Luo, Y., Alaghbandrad, A., Genger, T. K. & Hammad, A. History and recent development of multi-purpose utility tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 103, 103511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103511 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. An experimental study on the corrosion characteristics of the karst tunnel engineering area in Southwest China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 4047–4061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-018-1411-6 (2018).

Wang, S. Uneven settlement design and construction technology of underground integrated pipe gallery. Building Technol. Dev. 46, 22–24 (2019).

Darli, C. M., Aiping, T., Delong, H. & Jiqiang, Z. Large scale shaking table model test and analysis on seismic response of utility tunnel in non-homogeneous soil. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 20, 505–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11803-021-2035-6 (2021).

Hao, K. et al. Asymmetric deformation characteristics and mechanical behavior for tunnels in soft-hard inclined contact strata under high geo-stress: a case study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-022-02784-y (2022).

Abate, G., Grasso, S. & Massimino, M. R. Effect of soil heterogeneity on seismic tunnel lining forces. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 168, 107849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2023.107849 (2023).

Li, J., Liu, A. & Xing, H. Study on ground settlement patterns and prediction methods in Super-Large-Diameter shield tunnels constructed in composite strata. Appl. Sci. 13, 10820. https://doi.org/10.3390/app131910820 (2023).

Deng, B., Li, X., Li, P., Tian, J. & Li, J. Rationality determination method and mechanical behavior of underground utility tunnels in a ground fissure environment. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 81, 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02497-8 (2021).

Deng, B., Li, P., Li, X., Tian, J. & Zhi, B. Mechanical behavior of underground pipe gallery structure considering ground fissure. J. Mt. Sci. 19, 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-021-6867-3 (2022).

Yan, Y. et al. Failure analysis and deformation mechanism of segmented utility tunnels crossing ground fissure zones with different intersection angles. Eng. Fail. Anal. 139, 106456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2022.106456 (2022).

Sharma, J. S., Hefny, A. M., Zhao, J. & Chan, C. W. Effect of large excavation on deformation of adjacent MRT tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 16 (2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0886-7798(01)00033-5 (2001).

Hu, H., Lan, Y., Liu, Y. & Qiu, W. Experimental study on the damage performance and forced response of concrete lining in fault-crossing tunnel. Sci. Rep. 14, 2120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52318-7 (2024).

Zhang, D., Hu, Z., Lu, G., Wang, R. & Ren, X. Experimental study on deformation mechanism of a utility tunnel in a ground fissure area. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020 (6758978). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6758978 (2020).

Li, F. et al. The Effect of Intersection Angle on the Failure Mechanism of Utility Tunnel. Advances in Civil Engineering 8864676. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8864676 (2020).

Wu, X., Nie, C., Li, D., Qiu, F. & Tang, Y. Structural Response of a Prefabricated Utility Tunnel Subject to a Reverse Fault. Buildings 12(8), 1086. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12081086

Rakitin, B. & Xu, M. Centrifuge modeling of large-diameter underground pipes subjected to heavy traffic loads. Can. Geotech. J. 51, 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2013-0253 (2014).

Malhotra, M., Sahu, V., Srivastava, A. & Misra, A. K. Experimental and numerical investigation of the effect of pre-existing utility tunnel on the bearing capacity of shallow footing in sandy soils. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 18, 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1108/jedt-04-2019-0102 (2019).

Qiu, Y., Feng, K., He, C., Zhang, L. & Wang, C. Investigation of the ultimate bearing capacity of a staggered assembly segmental lining for an urban gas transmission tunnel. Sustainable Cities Soc. 48, 101551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101551 (2019).

Chen, Z., Liu, Z., Sun, K. & Wu, B. Measurement error analysis and test verification of scaled model mixed simulation test. J. Building Struct. 38, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.14006/j.jzjgxb.2017.08.018 (2017).

Zhang, L., Wang, J., Kaliakin, V. N. & Tang, Y. Load-bearing characteristics of square footing on geogrid-reinforced sand subjected to repeated loading. J. Cent. South. Univ. 27, 920–936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11771-020-4341-y (2020).

Wang, J., Zhang, L., Tang, Y. & Huang, S. B. Influence of reinforcement-arrangements on dynamic response of geogrid-reinforced foundation under repeated loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 274, 122093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.122093 (2021).

Silva, A. C., Barcarji, E., Virgens, J. P. & Tassi, A. d. A. Microconcreto de Alto Desempenho: propriedades e comportamento de Pilar à Flexão normal Composta. Matéria (Rio De Janeiro). 23 (03), e12161. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-707620180003.0495 (2018).

Zhang, C., Zhang, J., Ren, Q., Xu, J. & Wang, B. Study on the material properties of microconcrete by dynamic model test. Materials 15 (10), 3432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15103432 (2022).

Gu, X., Xu, Y. & Zhang, W. Study on Stiffness Deterioration of RC Beams after Cracking. Structural engineer 21(05), 22–25. (2005). https://doi.org/10.15935/j.cnki.jggcs.2005.05.005

GB 51354 – 2019. Technical Standard for Operation, Maintenance and Safety of Urban Underground Utility Tunnels (Standardization Administration of China, 2019).

Yang, Z., Li, Y. & Yang, R. Analysis on cracks of Cast-in-Place utility tunnel induced by uneven settlement: a case study ofutility tunnel of Fuzhou Southeast freeway. Tunn. Constr. 41, 2098–2105 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Research on natural foundation bearing capacity and foundation pit settlement of prefabricated utility tunnel. Adv. Civil Eng. 2022 (5361199). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5361199 (2022).

Wang, S., Jierula, A., Wang, P. & Zhao, Y. Mechanical behaviors of easy cracking zones of precast rectangular utility tunnels. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15, e00648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00648 (2021).

Yang, W. et al. Deformation mechanism and mechanical behavior of tunnel within contact zone: a case study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 5657–5673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-021-02255-w (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power Doctoral Innovation Fund (No. BCJJ202418), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52468047), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (No. 2022GXNSFDA035081), the High-Level Innovation Team and Outstanding Scholars Program of Guangxi Institutions of Higher Learning of China (Gui Jiao Ren Cai [2020] 6). Sincere gratitude is extended to Dassault Systèmes for the support provided by ABAQUS 2024 (Abaqus Learning Edition) in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Paper revision and polishing, Z.C. and J.W.; laboratory experiment, Z.L. and Y.T.; paper writing, Z.C.; literature research, Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, Z., Wang, J., Lin, Z. et al. Influence of soil-rock composite stratum on mechanical response and failure modes of underground utility tunnel. Sci Rep 15, 7731 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91893-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91893-1