Abstract

Retinal cone photoreceptors are specialized neurons that capture light to begin the process of daylight vision. They occur as individual cells (i.e., single cones), or as combinations of structurally linked cells, such as the double and triple cones found in the retinas of non-eutherian vertebrates. These different morphological cone types form mosaics of varying regularity, with single and double cones patterned as nearly perfect lattices in the retinas of many bony fishes (teleosts) and some geckos. Although double cones were first reported over 150 years ago, how they form (i.e., whether from coalescing single cones, or from structurally linked cone progenitors) remains uncertain. In turn, whether there is a general vertebrate sequence in appearance of morphological cone types and mosaics is unknown. Here, the developing retinas of seven species of teleosts were examined revealing that only single cones, arranged in hexagonal-like mosaics, were present at the earliest stages of photoreceptor differentiation. Double cones arose from coalescing single cones and the formation of multi-cone type mosaics (such as the square mosaic, where each single cone is surrounded by four double cones) followed different dynamics depending on whether the species was altricial or precocial. Single cones were therefore the primordial cells from which all multi-cone types arose and hexagonal-like mosaics preceded other mosaic patterns. Based on observations from transitional retinas, we propose a model for mosaic transformation from hexagonal to square. The double cones of fishes and those of land vertebrates constitute an example of convergent evolution to achieve the elliptical waveguide structure, likely for improved spatio-temporal resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For many animals, vision is essential to capture prey, avoid predators, select mates, and navigate the environment. Vision starts with the absorption of light by photoreceptors in the retina and its transduction into electrical signals that the brain can interpret1. In vertebrates, there are two major classes of photoreceptors: rods and cones. Rods are single, tubular cells that are highly sensitive to light and operate in dim environments. Cones occur as single or linked cells, have somas that exhibit variable cross sections, and operate in bright light conditions1,2. Whereas all rods in an animal typically express the same visual pigment (the protein-chromophore complex that absorbs light), cones often express different visual pigments and mediate high resolution colour vision2,3.

Cones form mosaics over the retinal surface that vary in regularity and cell composition. In the human foveola, for instance, single cones are patterned in a hexagonal lattice where each cell is surrounded by an average of six neighbours4,5. In many teleost fishes and some geckos, single and double cones (Fig. 1A–C) form patterns that vary with species, retinal location and developmental stage (Fig. 1C–E)6,7,8,9,10. Although double cones range widely in their morphology, from unequal (principal and accessory) members to equal (twin) cones, and with variable contact surface2,8,11,12,13,14, some key aspects can be used to define them. Double cones consist of two cells that are structurally connected along a common partition made of two parallel apposing membranes and exhibiting an approximately elliptical cross section at the level of the inner segment. This definition is more extensive than what has been considered a double cone before (e.g., two coupled cone cells12). It removes from contention what we have previously termed pseudo-double cones15, which are paired cones that dissociate into individual cells upon retinal extraction, as occurs with some cyprinid12 and sucker15 retinas when isolated for microspectrophotometry recordings. Fully differentiated, light-adapted fish double cones typically exhibit 1 sub-surface cisterna running parallel to the plasma membrane of each member16,17,18 and, at least in one cyprinid fish, the tench, Tinca tinca, double cones are electrically coupled19. The source of adhesion between double cone members at the level of the common partition is mostly unknown though junction-like structures have been reported in the chicken20,21 and in zebrafish22. In the latter, Crumbs proteins take part in cell adhesion and Crumbs 2b localizes to junctional regions between cones including the double cone partition22,23.

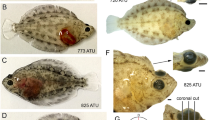

Retinal morphology and cone patterning during early photoreceptor differentiation. (A) Radial light micrograph of the retina of sablefish 97 days post-fertilization (dpf) following yolk-sac absorption. The relative position of cones in this developing retina was characteristic of all species studied except for the zebrafish. A red arrow points to the adjoining membrane complex between two members of a double cone (dc). (B) Schematic of the two morphological cone types [single cone (sc) and double cone] present in (A). (C) Tangential light micrograph of the retina in (A) showing the disposition of cones at the level of the inner segment ellipsoid. The lower part of the figure shows a square mosaic, where each single cone is flanked by four double cones. The area within the white rectangle diverges from the square mosaic pattern. (D, E) Radial (D) and tangential (E) light micrographs of the zebrafish retina at 15 dpf. The three cone types [double cone, long single cone (lsc), and short single cone (shsc)] occupy different tiers of the photoreceptor layer (D). The mosaic (E) spans double cone myoids to single cone outer segments. Ultrastructure details of the retinas from 97 dpf sablefish and 15 dpf zebrafish (panels A, C,D, E) are shown in Fig. 2. (F) Electron micrographs showing the disposition of single cones during their early morphological differentiation [the inner segment contains endoplasmic reticulum (er) and, when present, mitochondria (m)]. The mosaic schematics represent approximate tracings of cones, which are darkened. Each blue polygon links a cone’s immediate neighbours. (G, H) Micrographs and associated mosaic schematics of embryo or young larvae of the four altricial (G) and three precocial (H) species examined. The last column in each set of panels shows magnified views of the apposing plasma membranes between single cones (opposing white arrowheads); all are radial views except for the Senegalese sole panel. The white rectangle (asterisk) within the Atlantic halibut half-panel is magnified to its right. Days post-fertilization of the samples in (F–H) are indicated to the right of the panels. c connecting cilium, cn cone nucleus, cos cone outer segment, cpe cone pedicle, dcos double cone outer segment, hc horizontal cell, is inner segment, lcel long cone ellipsoid, lcos long cone outer segment, n nucleus, nu nucleus of retinal pigment epithelium cell, olm outer limiting membrane, os outer segment, pg pigment granule, rn rod nucleus, ros rod outer segment, rpe retinal pigment epithelium, rs rod spherule, shcel short cone ellipsoid. The magnification bar at the bottom left of (B) = 10 μm for (A–D) and 7.5 μm for (E). The magnification bar on the bottom right of each electron micrograph in (F–H) = 0.5 μm.

The most prevalent cone lattices in adults of non-mammalian species are the square, where each single cone is surrounded by four double cones (Fig. 1C), and the row, where rows of single cones alternate with those of double cones8. Mosaics are believed to improve all aspects of visual function including colour discrimination, spatial acuity, and motion detection6,8,24, and computer simulations have shown that the accuracy of neural image representation increases with mosaic regularity25,26. Despite the purported importance of cone mosaics and the discovery of the square lattice over 150 years ago27, how double cones and their mosaics arise remains debated. Likewise, whether there is a general progression in vertebrate cone mosaic development has not been investigated.

Studies of retinal development in fishes have suggested two alternative mechanisms of double cone formation that appear to correlate with precocial versus altricial development. These two categories refer to the pace of development whereby precocial species develop more rapidly and are generally self-sufficient sooner. In regards to the retina, precocial species develop cones and rods in short succession16,28 whereas the appearance of these two photoreceptor types is more staggered in altricial species29,30,31,32. The first mechanism of double cone formation, proposed for guppy, Poecilia reticulata, and zebrafish, Danio rerio, involves direct development from structurally linked progenitor cells16,28. The second, advanced for fishes that undergo a prolonged metamorphosis, like flatfishes, proposes coalescence of differentiated single cones17,18,29,30,31. Ultrastructure observations from a few marine fishes have shown single cones linking together through the development of a multi-layer membrane complex as the larval hexagonal lattice is replaced by a square mosaic17,18,33. Such observations for altricial species17,29,30,31,32 are not mirrored in precocial species16,34,35,36. In the latter, double cones and rods seem to appear at the same time or shortly after the first single cones, but lack of detailed ultrastructural observations prevents determination of double cone morphological origin or any associated changes in mosaic patterning.

It has also been suggested that different mosaic programs are initiated in the peripheral, circumferential germinal growth zone of the retina (ora serrata) as the eye of some fish species grows30,37,38. How cone and mosaic formation may differ between peripheral and central retina in these species is also unknown. Beyond fishes, the structural mechanisms of double cone formation have not been studied. In the chicken, Gallus gallus, however, the principal member of the double cone starts to differentiate at least 20 h before the accessory member39, suggesting that they are not the product of a single final mitotic event in which the daughter cells fail to separate completely. Instead, they appear to arise from different progenitors (as per zebrafish double cones)40 and coalesce later-on to form the mature double cone. This research was undertaken to determine the morphological origins of multi-cone types (e.g., the double cone) and associated mosaics in several bony fish (teleost) species, and to reveal whether there is a general vertebrate sequence in mosaic formation.

Results and discussion

Development of morphological cone types and mosaics

To explore the morphological origins of multi-cone types, the earliest stages of photoreceptor differentiation were characterized in four altricial (Atlantic halibut, Hippoglossus hippoglossus; Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis; sablefish, Anopoploma fimbrium; European anchovy, Engraulis encrasicolus) and three precocial (rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss; threespine stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus; zebrafish) teleost species (Table 1; Figs. 1 and 2). All developed rods and various cone types which, in the light-adapted retina, overlapped outer segments (the ciliary processes that house the visual pigments) radially (Fig. 1A–C), though zebrafish cones could be strongly tiered (Fig. 1D,E). Regardless of species, at the start of inner segment ellipsoid formation, only single cones were present, and these were primarily distributed in hexagonal-like mosaics (blue polygons, Fig. 1F), though cone cross sectional shapes varied with species. In altricial species, differentiated single cones persisted as the only photoreceptor type, arranged in hexagonal lattices, during the early larval period, prior to active prey hunting (Fig. 1G). This was only the case for precocial species prior to hatching (only the connecting cilium, which gives rise to the outer segment, had started to form in some cones at this stage, Fig. 1H). Neighbouring single cones abutted inner segments (opposing white arrowheads, Fig. 1G,H) with no signs of subsurface cisternae below the plasma membranes, in contrast to their presence as part of mature double cone partitions16,17,18 (Fig. 2). More importantly, there was no sign of any ellipsoid cross section that was elliptical (let alone having a central partition), the most obvious characteristics of double cones.

Ultrastructure of photoreceptors from the retinas of 97 dpf sablefish and 15 dpf zebrafish with emphasis on double cone partitions and junction-like regions. (A) Tangential electron micrograph of the juvenile sablefish retina showing the elliptical and circular profiles of double cones (dc) and single cones (sc), respectively. Black arrowheads point to partitioning membranes of double cones. The area within the white rectangle is magnified in (B). (B) Double cone ellipsoid showing “decorated” plasma membranes with minute electron-dense globular structures on either side. The area within the pink rectangle shows part of the partition that is similar to the junction-like processes identified in zebrafish22; electron-dense filaments (dark extensions between the two membranes) appear to link them together. (C) Radial view of a multi-layer double cone partition in the central retina of 15 dpf zebrafish. (D) Radial view of a “paired cone” from the peripheral retina of 15 dpf zebrafish near the circumferential growth zone showing two singular membranes apposed together (opposing white arrowheads). The area within the white rectangle is magnified in (E). (E) The apposing membranes are not “decorated” or show any signs of structural connectivity. (F) Radial micrograph of multiple cones from the central retina spanning the nuclear to myoid/proximal ellipsoid region of 15 dpf zebrafish. Black arrowheads point to multi-layered double cone partitions. Müller glia form electron-dense junctions with photoreceptors at the proximal myoid region constituting the outer limiting membrane (olm); these junctions appear to form a continuous membrane under light microscopy, hence the historical misnomer. The area within the white rectangle is magnified in (G). (G) Magnified view of two junctions between Müller glia (Mg) and cone photoreceptors. er endoplasmic reticulum, m mitochondria, n nucleus, os outer segment, pg pigment granule. The magnification bar on the bottom right of each electron micrograph = 0.5 μm.

The lone presence of single cones and their hexagonal-like patterning at the earliest stages of photoreceptor differentiation appear common between teleosts and tetrapods with double cones such as amphibians41 and birds42. Comparison of mosaics from larval teleosts with those of embryonic chicken, pre-metamorphic African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis) tadpole, and adult human (Homo sapiens) revealed similar mean neighbour numbers (Fig. 3). This suggests a universal program for vertebrate cone mosaic development that begins with single cones arranged in hexagonal-like mosaics. Near-neighbour spatial analyses further demonstrated that the mosaics of teleosts were more regular than those of chicken and frog, and that only altricial fishes (e.g., Atlantic halibut) and human showed higher order (lattice-like) periodicity in their mosaics, as conveyed by the clumping of data into periodic foci in the autocorrelation plots8,43. Accordingly, the regularity of the hexagonal lattice was similar for these two species (Fig. 3).

Spatial analysis of representative retinal mosaics from the central retina of Atlantic halibut, zebrafish, chicken, African clawed frog and human. The developmental stages shown are: 96 days post-fertilization (dpf) (start of metamorphosis, Atlantic halibut)22; 8 dpf (zebrafish), embryonic day 16 (chicken)32, stage 45 pre-metamorphic tadpole (African clawed frog)31; adult (human)4. Only single cones could be discerned in the micrographs. The number of near neighbours was statistically the same between species (2nd panel row; ANOVA, F4,719 = 3.03, p = 0.017; SNK and Tukey HSD p = 0.064). Nearest neighbour analyses of cone centroids (3rd and 4th panel rows) illustrate the near neighbours of a single cone, including its nearest neighbour in red, and their frequency distribution [statistics (in µm) are the mean nearest neighbour distance, its standard deviation (SD), the minimum (min) and maximum (max) nearest neighbour distances, and the regularity (reg) index = mean/SD]. The Voronoi domain analyses (5th and 6th panel rows) show the Voronoi tessellation of single cone domains and their frequency distribution [statistics (in µm2) are the mean area (domain), its standard deviation (SD), the minimum (min) and maximum (max) areas, and the regularity index = mean/SD]. The autocorrelograms (7th panel row) and associated density recovery profiles (8th panel row) show that only the Atlantic halibut and human mosaics are lattices, i.e., exhibit higher order periodicity. The ER is the effective radius (or exclusion zone) which represents the size of the null region at the centre of the autocorrelogram. The ER for each species corresponds, approximately, to the mean inner segment ellipsoid cone diameter, as would be expected from the tight cone packing. The chicken micrograph is part of Fig. 4, 2nd panel, in the publication: Bruhn, S.L. & Cepko, C.L. Development of the pattern of photoreceptors in the chick retina. J. Neurosci. 16, 1430–1439 (1996). The copyright license is: © 1996 Society of Neuroscience 0270–6474/96/161,430–10$05.00/0. The African clawed frog micrograph is part of Fig. 4A in the publication: Chang, W.S. & Harris, WA. Sequential genesis and determination of cone and rod photoreceptors in Xenopus. J. Neurobiol. 35, 227–244 (1998). The copyright license is: 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. CCC 0022-3034/98/030227-18. The human fovea centre (foveola) micrograph is part of Fig. 1B in the publication: Curcio, C.A., Sloan, K.R., Kalina, R.E. & Hendrickson, A.E. Human photoreceptor topography. J. Comp. Neurol. 292, 497–523 (1990). The copyright license is: © 1990 WILEY-LISS, INC.

Following the start of metamorphosis (a process during which the larva develops into a juvenile), single cones in the central retina of altricial species began coalescing and altering the hexagonal lattice (Fig. 4). Adjacent plasma membranes started to become multi-layered (black arrowheads) by incorporating sub-surface cisternae (double white arrowheads) that linked to form parallel cytoplasmic membranes (Fig. 4A–C,G–L). This process occurred independently at multiple contacts between neighbouring cones (Fig. 4E,F,K,L), with the earliest incidences occurring at the level of the inner segment myoid (Fig. 4B,C). Coincidently, some cones started to change ellipsoid cross-section from hexagonal to pentagonal (black asterisk) via the development of a flatter common surface with a neighbour (Fig. 4A,M). At this stage, cytoplasmic protrusions between neighbouring cones were also common resulting in cog-like deformations of adjacent plasma membranes (black circle, Fig. 4A). As metamorphosis progressed, the hexagonal lattice transformed into a mosaic of varying regularity, depending on species (Fig. 4D,N,O,Q,R). Although there was a general trend toward the square mosaic in all species except for the anchovy (Fig. 4S), individual single cones could be seen surrounded by 3 double cones in triangular formation (Fig. 4O) and groups of 2–3 single cones could be flanked by 6–8 double cones (Fig. 4D,N)29,30,31. In the Atlantic halibut, a random mosaic of single, double and triple cones also develops in a restricted area of centrodorsal retina30,31. This process involves simultaneous linkage of multiple neighbouring cones and the formation of triple cones by a similar process to that described for double cones (Fig. 5). Together, these observations and the lack of differentiating cone progenitors at this stage of development in flatfishes29,37,44 argue for coalescence of single cones as the source of multi-cone types and the progressive transformation of the hexagonal lattice into a square mosaic.

Development of the double cone partition membrane complex in the central retina of altricial fishes. (A–F) Electron micrographs showing mosaics at early (A) and late (D) metamorphosis of Atlantic halibut, with corresponding cones in radial view (B, C and E, F). Opposite white arrowheads point to apposing membranes between two cones (A–C, E,F). Black arrowheads indicate a multi-layered section of apposing membranes (A, C–F) and double white arrowheads point to individual sub-surface cisternae (F). The black circle in (A) shows a cog-like protrusion of one cone into another and the black asterisk indicates a cone ellipsoid with pentagonal morphology; cp., calyceal process. The double black arrowhead in (D) indicates two single cones likely to become a double cone. The white rectangles in (B) and (E) are magnified in (E) and (F), respectively. (G–P) Micrographs illustrating similar double cone partition formations in Senegalese sole (G-L) and sablefish (M–P). (G–L) The retina of metamorphosizing Senegalese sole shows many single cones that are linked (black arrowheads, G); the white asterisk indicates one of three cones linked in series. The white and black rectangles in (H) are magnified in (I) and (J), respectively; the white rectangle in (K) is magnified in (L). (M–P) The sablefish mosaic during early (M) and late (N) metamorphosis showing pentagonal morphology of a cone ellipsoid (black asterisk) altering the hexagonal lattice (M), and apposition of membranes between double and single cones. (O) Single cone showing contacts (1–6) between its hexagonal faces and three surrounding double cones. (P) Magnified view of a double cone membrane partition being formed. (Q–T) Cone mosaics in the larval anchovy (Q, R) and details of the triple cone (S, T) in the juvenile. The apposing membrane complexes between central (ce) and lateral (lat) cones show multiple sub-surface cisternae (double white arrowheads, T). (U) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and corresponding fluorescence images of cryosections from Atlantic halibut incubated with a mouse monoclonal antibody against α-tubulin (yellow fluorescence). Hexagonal mosaic units shown in blue. Yellow and green arrowheads point to fluorescence of plasma membranes of single cones and external membranes of double cones, respectively. Red arrowheads indicate double cones without partition fluorescence; double yellow arrowheads point to double cone partial partition fluorescence. Same structures are indicated in corresponding DIC and fluorescence images. c connecting cilium, is inner segment, m mitochondria, n nucleus, os outer segment, pg pigment granule, ros rod outer segment. The magnification bar on the bottom right of each electron micrograph in (A–T) = 0.5 μm. The magnification in (U) = 5 μm holds for all panels.

Formation of multi-cone types, including triple cones, in the centro-dorsal retina of Atlantic halibut undergoing metamorphosis. (A–D) Tangential (A, B) and radial (C, D) micrographs illustrating the first stages of multilayer partition complex formation between neighbouring cones. The white rectangles in (A, C) are magnified in (B, D), respectively. Opposing white arrowheads indicate apposing plasma membranes between cones without sub-surface cisternae. Multilayered regions of apposing plasma membranes are indicated with black arrowheads and individual sub-surface cisternae with double white arrowheads. (E–J) As metamorphosis progresses, more complex patterns appear that include linkage of four cones (E, G) via multilayer partitions at different stages of assembly (F). The white rectangle in (E) is magnified in (F). Developing triple cones (t) (H) form by adhesion of three single cones through the establishment of multi-layered partitions (I, J) by incorporation of sub-surface cisternae, in a similar process to that described for double cone formation. The white and black rectangles in (H) are magnified in (I) and (J), respectively. cp. calyceal process, is inner segment, m mitochondria, os outer segment, sc single cone. The magnification bar on the bottom right of each electron micrograph = 0.5 μm.

These conclusions were further supported by patterns of α-tubulin binding to single cones versus developing double cones (Fig. 4U). Tubulins are found radially, as part of microtubules, along the perimeter of the inner segment of cones, adjacent to the plasma membrane, but not along double cone partitions45. In pre-metamorphic retinas, α-tubulin was prominent at the inner to outer segment boundary, with punctuated yellow fluorescence along the inner segment periphery revealing the calyceal processes (i.e., the finger-like extensions of the inner segment plasma membrane that surround the base of the outer segment; yellow arrowheads, Fig. 4U)46. In transitional mosaics, double cones showed partial (double yellow arrowheads) to no (red arrowheads) fluorescence along the common partitioning membrane complex (Fig. 4U). As tubulins and calyceal processes surround single cones, but only the external (non-common) surfaces of double cones45,46, this variation in partition fluorescence could only have arisen from coalescing single cones and not from structurally-linked progenitors, which would lack partition fluorescence. Accordingly, as single cones coalesced, the calyceal processes became absorbed along the common partition surface and its fluorescence progressively disappeared, leaving only the external surface fluorescence (green arrowhead, Fig. 4U).

The mechanism by which the hexagonal lattice transforms into a square lattice is unknown. By mapping individual cones of Atlantic halibut from transitional mosaics (Fig. 6A,B) to the hexagonal matrix (Fig. 6C) based on near neighbour morphology and contacts, double cone formation appeared to follow an approximate pattern of neighbour linkage (area within yellow rectangle, Fig. 6C). Application of this motif onto the hexagonal lattice (Fig. 6D) led to a rudimentary square mosaic which, upon rotation and translation of its elements, would result in the square lattice (Fig. 6E). Single blue (SWS2 opsin expressing) cones form such a pattern in transition areas where the hexagonal lattice is transforming into a square mosaic and the tilt in cone axons betrays their lateral displacement31. The abundant cog-like cytoplasmic contacts between neighbouring cones, perhaps enhanced by coupling of calyceal processes (right-most schematic in Fig. 6E), may provide the traction for rotation given an initial force that could be intrinsic (e.g., changes in cone shape)47,48 and/or extrinsic (e.g., retinomotor movements, which start around the time of active foraging)49.

Model of mosaic reorganization from hexagonal to square. (A) Light (DIC) micrograph of an area of Atlantic halibut retina transitioning from hexagonal lattice (upper right, blue polygon) to square mosaic (lower left). Members of a double cone are linked by a red line. (B) Schematic reconstruction of the cones in (A) based on cone shape and contacts. (C) Transposition of cone patterns in (B) to the hexagonal matrix. The cones encased within the yellow rectangle illustrate a repeat link pattern for double cone formation. (D) Application of the pattern in (C) to the hexagonal matrix showing single cones in blue and double cones as red ellipses. (E) Model illustrating rotation of repeat pattern in (D) (top) to form the square mosaic in post-metamorphic Atlantic halibut (bottom), potentially involving forces acting on the “cog-like” protrusions between cones and the intercalating calyceal processes (middle).

Coalescence of single cones to form double cones and the square mosaic was also observed in precocial species, though the process was much more rapid and any hexagonal-like patterning was brief and highly divergent from a lattice (Fig. 7). Both in rainbow trout and threespine stickleback, developing double cones were visible in the embryo within one day of single cone appearance, often forming a rudimentary square mosaic (Fig. 7A–D,L,M). As was the case with altricial species, partitions became multi-layered at different points of contact between joining double cone members (Fig. 7E,G–K,N) through the incorporation of subsurface cisternae (Fig. 7B,F,P). As the square mosaic continued forming (Fig. 7G), cytoplasmic protrusions between neighbouring cones became apparent (Fig. 7H,I) as did variations from the square mosaic pattern (Fig. 7E,N,O). The square mosaic unit of rainbow trout and, to a lesser extent, that of threespine stickleback, comprised single cones positioned both at the centre (blue asterisk, at the hypothetical intersection of double cone partitions) and corner locations (red asterisk, facing neighbouring double cone partitions) (Fig. 7G,J).

Development of the double cone partition membrane complex in the central retina of precocial fishes, and comparison with peripheral retina. (A–K) Electron micrographs from embryonic [two days (A, B) and one day (C, D) prior to hatching] and yolk sac embryo (15 days post hatching) rainbow trout. White rectangles in (A, C,J) are magnified in (B, D,K), respectively. Prior to outer segment formation, some apposing membranes between single cones become multi-layered (black arrowhead, B) and square mosaic formation is visible (C). Following outer segment appearance (E–K), cone patterning can vary from the square mosaic (e.g., 6 double cones surrounding a single cone, E) as double cone recruitment of sub-surface cisternae continues (double white arrowheads, F). The square mosaic unit contains both centre (blue asterisk) and corner (pink asterisk) single cones (G, J) with prominent intrusions of the plasma membrane between inner segment ellipsoids (black circles, H,I) and filopodial (f) contacts between myoids of neighbouring cones and Müller glia (Mg) (K). (L–P) Micrographs from threespine stickleback at hatching (L, M) and upon yolk absorption (N–P). The white rectangle in (L) is magnified in (M). (L, M) Primordial double cones and square mosaic units prior to outer segment formation. (N–P) Variable mosaic patterns, including 5 double cones surrounding a single cone (white rectangle, O), among square mosaic units with only centre cones (blue asterisk, N). (P) Incorporation of sub-surface cisternae (double white arrowheads) at different contact sites, from multi-layered (black arrowhead) to devoid of cisternae (opposite white arrowheads), between members of a double cone. (Q–AA) Micrographs from zebrafish larvae at 8 days post-fertilization (dpf, Q-W) and 15 dpf (X–AA). Short single (UV) cones (shcos) are vitreally displaced with respect to other cone types at 8 dpf (Q, V). Most cones abut plasma membranes lacking sub-surface cisternae (opposite white arrowheads, S) and cog-like cytoplasmic protrusions at regions of contact are common (black circles, R), perhaps due to interlocking calyceal processes (white rectangle shows calyceal processes in a no contact zone, R). Some cones start developing multi-layer partition membranes (black arrowheads, T,U) by amalgamation of sub-surface cisternae (double white arrowheads, W) becoming double cones (U, V). At 15 dpf, the mosaic remains hexagonal-like (X) and long single cones are displaced vitreally with respect to double cones (Y), whose partitions continue to incorporate sub-surface cisternae (double white arrowheads, Z) as opposed to contacts involving single cones (opposite white arrowheads, AA). (A’–K’) Micrographs from the peripheral growth zone in juvenile/adult retina. The ora serrata of juvenile (post-metamorphic) Atlantic halibut shows cone nuclei in hexagonal formation (blue hexagon, A’) whereas nearby differentiated cones are arranged in a square mosaic with varying numbers of corner cones (pink asterisks, B’). Deviation from a square lattice is common (C’) and single cones link with neighbours by forming multi-layered partitions (D’,E’) to become double cones (F’). Adult Atlantic halibut shows double cones with similar partition characteristics (G’). The peripheral retinas of juvenile European anchovy (H’), rainbow trout (I’) and 15 dpf zebrafish (J’,K’) show but single cones without subsurface lamellae near the undifferentiated ora serrata. Rods appear after the first cones (J’). The white rectangle in (J') is magnified in (K'). c connecting cilium, cos cone outer segment, dcos double cone outer segment, er endoplasmic reticulum, lcos long cone outer segment, m mitochondria, n nucleus, olm outer limiting membrane, os outer segment, pg pigment granule, rpe retinal pigment epithelium, r rod, ros rod outer segment, sc single cone, shcos short cone outer segment. The magnification bar on the bottom right of each electron micrograph = 0.5 μm.

The zebrafish showed very different cone patterning to other species though the process of double cone formation remained similar (Fig. 7Q–AA). At 4 days post fertilization (dpf), the outer segments of short single (ultraviolet (UV)-sensitive) cones were absent and all cones occupied the same layer radially (Fig. 1H). By 8 dpf, two tiers of cones were present: a population of single cones near the retinal pigment epithelium where multi-layered inner segment membrane complexes were starting to appear, and a vitreally-displaced population (the UV cones) with the largest outer segments (Fig. 7Q–U)50. As partitions became more complex (Fig. 7T–W), through recruitment of sub-surface cisternae (Fig. 7W), one member of the double cone pair became slightly displaced from the other along its length (Fig. 7V). By 15 dpf (Fig. 7X–AA), the mosaic remained hexagonal-like (Figs. 1E and 7X), but the three morphological cone types (double cones, long and short single cones) were radially tiered (Figs. 1D and 7Y–AA), as in the adult34.

Our results for zebrafish may help to clarify the structural origin of double cones in this species. An early study using the zpr-1 antibody (against arrestin-3a) showed exclusive binding to double cones in adult zebrafish28. This antibody labelled a small patch of cells in the ventral retina of the 2 dpf larva, shortly after the final photoreceptor mitotic division. By 54 h post-fertilization (pf), or about 6 h before first outer segment appearance, the stained and unstained cells formed a pattern supposedly reminiscent of the adult lattice28. This interpretation, however, is incongruent with more recent work showing that the adult lattice only appears between 20 and 36 dpf38. Some of the rounded cells labelled by zpr-1 at 54 h pf were thought to be separated by a fissure, suggesting that they were a pair of cells joined together28. In contrast, our observations of 4 dpf larvae show no conjoint cells and no evidence of an elliptical cross section reminiscent of a double cone. Our observations are, instead, in line with another structural study that reported only single cones at 8 dpf and discernable double cones at 12 dpf34. The zpr-1 label at 54 h pf28 corresponds, in our opinion, to the single cell circular profiles in our micrographs and suggest close proximity between such related cells (presumably, they are individual double cone members that have not linked yet).

The general process of double cone formation observed in the developing central retina of the embryo/larva of all species could differ from that in the peripheral growth zone of the juvenile30,37,38. In the ora serrata of post-metamorphic Atlantic halibut, prior to inner segment myoid development, cone nuclei displayed a hexagonal pattern (blue polygon, Fig. 7A’). Areas proximal to the undifferentiated (proliferation) zone of the ora serrata showed single cones linking to form double cones (Fig. 7B’) via a similar process of multi-layer partition development (Fig. 7D’–F’; also observed in the reproductive adult, Fig. 7G’), with deviations from the square mosaic (Fig. 7C’) as seen in the central retina (Fig. 4). Nonetheless, the presence of occasional corner cones and rapid square mosaic assembly (Fig. 7B’) suggested a more precise program resembling that of rainbow trout and threespine stickleback (Fig. 7A–P). Corner cones disappear from the peripheral retina of juvenile trout and other salmonid fishes as the square mosaic forms and may play a role in its formation51. Radial images from the peripheral retina of juvenile European anchovy (Fig. 7H’), rainbow trout (Fig. 7I’) and 15 dpf zebrafish (Fig. 7J’,K’) showed only single cones near the proliferating germinal zone. This evidence indicates a similar process of double cone formation in the periphery of the juvenile/adult to that in the central retina but with dynamics that resemble those of precocial retinas. The latter may represent an accelerated version of altricial retinal development with modifications for corner cone presence, or a completely novel program that improves mosaic regularity by patterning of cone progenitors into square or row lattices a priori.

Potential functions of cones and mosaics

Except for the European anchovy, which develops specialized axially dichroic photoreceptors to sense the polarization of light52, likely for prey capture53, the formation of double cones and the square mosaic shortly before active prey hunting in the other species suggests a function in motion detection6,8,16,33,54,55. At hatching, oviparous larvae rely fully on their yolk sac for nutrition at a time when they are drifting in the ocean (altricial species) or largely immobile under rock or vegetation cover (precocial species). In these scenarios, a hexagonal mosaic of highly packed single cones with long outer segments and overwhelming expression of a single visual pigment tuned to the prevalent downwelling spectrum29,31,56 should maximize photon catch and achromatic detection of objects, such as the shadows of overhead predators. This system would, in addition, monitor environmental light to establish posture and swim depth, as observed for Atlantic halibut larva57. As the yolk sac is absorbed, this mosaic could also detect flashes of light scattered by prey microorganisms located immediately in front of the fish, mediating first feeding50. In support of this, action spectra derived from feeding experiments using the northern anchovy, Engraulis mordax, larva show a single peak (at 530 nm) function58 matching that from the ventro-temporal retina (foveal location containing one visual pigment)59 of the juvenile derived from optic nerve recordings59,60. Upon completion of yolk sac absorption, hunting prey becomes critical for survival requiring high resolution detection of targets and their tracking. In diurnal teleosts, this seems to require double cones and their chromatically regular mosaic lattices.

In general, the presence of double cones in vertebrate retinas appears linked to diurnal species requiring high resolution spatio-temporal perception for critical aspects of survival such as detection of food in spectrally complex environments. Eutherian vertebrates do not have double cones and the spectral composition of their mosaics is not as regular as that of teleosts, reptiles, or birds10,24,26,29,31,38,51,61,62,63. Yet these species, like human, show comparable or better visual capabilities to those of non-eutherian vertebrates26. The visual performance of humans suggests that alternative information processing strategies in the retina and brain64 compensate for the absence of double cones and chromatic lattices.

Double cones are elliptical waveguides that should improve spatio-temporal resolution

The double cones of chicken and anole lizard have different evolutionary lineage from those of zebrafish65. Based on this, and the presence of a double cone in non-eutherian land vertebrates that is absent in the retinas of ancient extant vertebrates, such as lampreys66, lungfishes66,67, coelacanth68 (Latimeria chalumnae), and sturgeons69, it has been argued that the double cones of fishes are not true double cones, but a linkage of single cones70. Although our findings are congruent with the idea that double cones arise from coalescing single cones in fishes, we do not agree with the statement that double cones in fishes are not true double cones for two main reasons. First, regardless of lineage, both double cone types (terrestrial and aquatic) have the cross-sectional morphology of elliptical waveguides and this extends to the packing of organelles (mitochondria and/or oil droplets) near the partitioning membrane to concentrate light propagation in the centre of the waveguide while providing polarization sensitivity71. Second, from a developmental perspective, it has not been shown that the land vertebrate double cone does not have similar ontogeny to the zebrafish double cone, i.e., that it does not originate from different precursor cells that link afterwards, at least prior to the appearance of the adult mosaic as shown in this manuscript. If the double cones of land vertebrates had different lineage from other fishes such as goldfish, Carassius auratus, which appears to show a full complement of “ancestral” single cones (UV, S, M and L) and various double cones11, and the ontogeny were different (perhaps the tetrapod double cone arises from linked progenitor cells, though presently unsupported from scant chicken data39), then there may be a case to rename fish double cones.

A new name, however, would disregard the structural and optical similarities between both types of double cones and their likely common function. The double cone seems to be a prime example of convergent evolution to achieve the elliptical waveguide form which likely increases spatio-temporal resolution by sensing the polarization of light71. An analogous example of evolutionary convergence would be the axially-oriented lamellae of cone photoreceptors in the polarization area of some anchovies59 and the microvillar disposition of retinular cells in the polarization area of insects72; these systems represent another strategy (orientation-dependent differential absorption) for polarization discrimination. In the case of vertebrate double cones, their outer segments (containing visual pigments with absorbance in the middle to long wavelengths) should enhance the waveguide’s polarization detection performance as polarization sensitivity increases when the wavelengths propagated approach the waveguide’s cross-sectional dimensions71 (in other words, by comparison, UV and short wavelengths would not be as efficient to generate polarization contrast). Their array disposition could be exploited by summation of outputs from like-oriented double cones by second order neurons such as ON bipolars. If more than one polarization element is present (like the two double cones with cross sections perpendicular to each other, as in the majority of diurnal fishes that have been examined8), then their summed array outputs could be subtracted to produce a much greater contrast signal than achievable by a single element or orthogonal pair. This is functionally analogous to the phased arrays73 used as receivers in engineering applications permitting exquisite motion detection. In this regard, the zebrafish is not representative of the majority of fishes as its singular orientation of the double cone would produce lower polarization contrasts at the local array level (though arrays with slightly different orientations of double cones along nearby “retinal spokes” could be compared). Although polarization vision in vertebrates is marred with controversy (except for the case of anchovies)59, it is very likely that the inconsistent results are due to a lack of proper illumination/stimulation procedures and insufficient resolution of the measuring techniques, which would obscure the double cone effect in polarization detection and, by consequence, spatio-temporal resolution. Enhancement of motion perception by the double cone elliptical structure over what could be achieved by other means, such as colour contrast from comparing outputs of chromatically diverse single cones, is indirectly supported by the foraging performance of small pelagic fishes, including guppy and threespine stickleback, on zooplankton55. Their performance is equally efficient under light backgrounds that only activate double cones, and this is likely based on achromatic motion perception55, the same function surmised for bird double cones74.

Evolution of cones and functionality

Our observations combined with those of others66,76 support an additional perspective regarding cone evolution and function (Fig. 8) that fits within the hypothesis of photoreceptors as feature detectors leading to colour vision as a by-product75. We postulate the ancient “primordial” vertebrate photoreceptor layer to consist of a single photoreceptor type with a combination of rod and cone attributes (e.g., long cylindrical outer segment, rapid phototransduction components, cone-like pedicle) as found in some extant ancient vertebrates like lampreys and lungfishes66,67. This photoreceptor would be patterned in hexagonal lattice, as per the photoreceptors of lampreys and lungfishes66, and would house an L visual pigment with maximum sensitivity around 560 nm, in accordance with the first chromophore-binding opsin to appear (LWS)76, and the exclusive presence of hydroretinal chromophore in marine fish retinas60. This achromatic retina would maximize photon catch (sensitivity) to extract basic features like changes in luminance for detecting targets (likely using ON and OFF pathways for background objects and prey/predators, respectively) as well as motion. It would also be able to monitor changes in daylight to establish swim depth. Today’s marine fish larvae seem to follow this retinal model by exclusive or overwhelming expression of one visual pigment peaking around 520 nm56, but based on RH2 opsins29,30,31,32 (which evolved later on; the purported order of opsin appearance from most ancient to most recent is: LWS, SWS1, SWS2, RH2, and RH1)76.

Evolution of photoreceptors and mosaics in fishes. Proposed scheme postulating a primordial retina with a single photoreceptor having a combination of cone/rod attributes and housing a long wavelength (L) visual pigment based on LWS opsin and retinal chromophore. Over time, complexity in photoreceptor structure and function was incorporated via the appearance of multiple opsin types as well as diversification of morphology and biochemical (e.g., phototransduction) components. The schematic only intends to show the chronological evolutionary appearance of opsin families. The number of photoreceptor types and the repertoire of expressed opsins and other biochemical attributes would vary with species, as exemplified by the photoreceptor diversity among today’s lampreys66. The appearance of double cones must have conferred a great ecological advantage (likely in improvement of spatio-temporal resolution) such that, with the exception of some anchovies, all diurnal teleosts that have been examined possess them, and the majority exhibit a square mosaic lattice. The opsin composition of the square lattice (which may or not comprise corner cones) is variable among fishes, with double cones typically consisting of M/L, M/M, or L/L members. Some fishes have these three chromatic combinations but in different ratios, potentially compartmentalized in different regions of the retina and subserving different functions. The same applies to single cones, which are typically UV or S, though L types have been reported in cyprinids11 and freshwater sunfishes (genus Lepomis) have only M types89. Cone-to-rod and rod-to-cone transmutations have been an ongoing phenomenon through evolutionary time as fishes (and other vertebrates) occupy new photic environments.

The appearance of SWS1 allowed for two information channels, receiving input from opposite regions of the spectrum to dissociate feature extraction75. Whereas the LWS (red) channel could achieve the spatio-temporal resolution for deciphering background objects and distance, the SWS1 (UV) channel specialized in low resolution detection of “white flashes” from nearby objects such as swimming zooplankton50, conspecific turns (shoaling behaviour)77, and territorial communication (as occurs in some present-day sucker species78). Additionally, it would have provided a means to assess overall UV intensity in the environment, which would help in preventing UV radiation damage79. We hypothesize that subsequent evolution of SWS2 and RH2 opsins allowed for enhanced detection of foreground and background features, respectively. These opsin families, which together span most of the visual spectrum in surface waters15,80, especially as longer wavelength subtypes evolved, progressively took over feature functions from the opsins subserving the spectrum extremes (SWS1 and LWS) and allowed for better matched photoreceptor complements with depth80. In fact, vision based on overwhelming expression of SWS2 and RH2 opsins is so widespread30,32,81,82 that at least one species, the Atlantic cod, has lost SWS1 and LWS from its genome altogether (though this species has a pelagic, planktivorous early life history)32. In ancestral vertebrates, SWS1 and LWS opsins could then be re-purposed for additional, novel functions (some as part of developing colour vision circuits)75 such as detection of sexual and territorial signals at close range (e.g., in present day fishes: the nuptial red throat of sticklebacks83, the UV markings on the faces of cichlids84, the “white” eye flash of suckers78) as well as oviposition sites (the sea raven, Hemitropterus americanus, chooses yellow-pink covered sponges to deposit its eggs82).

The importance of the UV cone for foreground visual tasks probably waned rapidly as SWS2 opsins appeared. In support of this, most life-long zooplanktivorous fishes (including rainbow trout, freshwater sunfishes, perch, and some cichlids) rapidly lose their UV cones by apoptosis and/or switching SWS1 for SWS2 during the larval/early juvenile period85,86,87,88,89. In fact, juvenile sunfishes only have a single M (RH2 opsin) cone surrounded by four L/L (LWS opsin) double cones forming the square lattice89,90. And likely, as in rainbow trout, all of these species comprise a prominent OFF pathway, anchored on M cone input91, that is used for hunting by silhouetting prey. Ultraviolet (SWS1 opsin) cones have also undergone a process of miniaturization and developmental pruning over evolutionary time, such that there are relatively few (compared to other cone types), if any, in post-larval retinas and their outer segments are much smaller than those of other cone types2,11,14,15,30,80,85,86,87,88, further supporting a progressively diminishing role in visual function. The zebrafish appears to be the exception as UV cone outer segments are wider at the base than those of other cone types and they are retained into adulthood34,38. However, even in this species, the adult devoid of SWS1 opsin may have similar predation success to wild type fish92 (an earlier study93 investigating this topic did not account for the less regular double cone mosaic of the “lots of rods” fish used94 where most UV cones are replaced by rods).

The appearance of double cones in jawed teleosts seems to have catapulted a change in mosaics favouring the square mosaic. Most marine fishes and at least some freshwater fishes95 with protracted larval development retained the ancestral hexagonal mosaic prior to metamorphosis, when a rudimentary (potentially achromatic) retina is sufficient for their limited behavioural repertoire. However, faster developing (precocial) fishes incorporated double cones early on during development and, in the majority, this was accompanied by patterning into a square lattice (the zebrafish being the notable exception), affirming the advantage of the double cone as an elliptical structure. We surmise that this advantage is primarily to enhance spatio-temporal resolution by incorporating polarization sensing, which would improve motion detection, something that evolved de novo with the appearance of double cones in non-eutherian vertebrates.

Methods

Animals and husbandry

All fish were raised from the fertilized egg and were the direct progeny of wild stock except for the zebrafish, which originated from Dr. Deborah Stenkamp’s laboratory at the University of Idaho (USA). Samples were collected from the embryonic egg stage, prior to eye formation, to the juvenile stage, characterized by active prey hunting and external morphology resembling the adult (Table 1). Eyes were also obtained from reproductive adults of several species following culling at hatcheries. Fish were euthanized by Tricaine Methanesulfonate (TMS) overdose. Specimens were collected during the light phase of their circadian rhythm and were light-adapted for at least 2 h prior to euthanasia. All holding and experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with Canadian Council for Animal Care guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care committees of Simon Fraser University (protocol # 1126B-10) and the University of Victoria (protocol # 2017-005). The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Rainbow trout originated from the Vancouver Island Trout hatchery (Duncan, British Columbia, Canada) where fertilized eggs were raised in the dark and yolk-sac embryos were progressively exposed to hatchery light from fluorescent light tubes (λ: 350–750 nm; irradiance: 4.5 × 1018 photons m− 2 s− 1; 14:10 h light: dark cycle) starting toward the end of yolk sac absorption, when active feeding commenced. Fish then experienced natural daylight. Water temperature was 10º C. Sablefish were raised in 5.4º C water at the Golden Eagle hatchery (Saltspring Island, British Columbia, Canada). Fertilized eggs remained in the dark until hatching, after which the larvae and juveniles experienced LED “white” light (λ: 400–700 nm, irradiance: 5.1 × 1016 photons m− 2 s− 1). Atlantic halibut were sampled from the Scotian Halibut Ltd hatchery (Clark’s Harbour, Nova Scotia, Canada) where they were raised in 7.5º C water under hatchery illumination (λ: 350–750 nm; irradiance: 1.2 × 1015 photons m− 2 s− 1; 14:10 h light: dark cycle). Senegalese sole fertilized eggs were collected from surface waters of the Cantabrian Sea and transported to the Spanish Institute of Oceanography (Santander, Cantabria, Spain) where they were raised in 18.5º C water under a similar light regime to that described for Atlantic halibut. European Anchovies were collected from the Gulf of Gascoigne and raised in 20º C water at the IFREMER (L’Houmeau, Charente-Maritime, France) in incubators equipped with fluorescent tubes (14:10 h light: dark cycle). Marine threespine stickleback were raised from fertilized eggs in the aquatic facility of the Zoology Department at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) in 17º C water (16:8 h light: dark cycle) under fluorescent tubes. The zebrafish originated from a dedicated facility in the Biology Department at the University of Idaho with water at 28.5º C and illumination provided by fluorescent tubes (14:10 h light: dark cycle). Fertilized eggs of rainbow trout, Atlantic halibut, sablefish, and threespine stickleback were obtained by artificial spawning of broodstock.

EPON histology

The entire bodies of euthanized embryos/larvae, and the eyecups (eye without iris and lens) of juveniles/adults, were fixed in primary fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.08 M PBS, pH = 7.4) at 4ºC for a minimum of 72 h. These were then rinsed in 0.08 M PBS and post-fixed in secondary fixative (1% osmium tetroxide in 0.08 M PBS) for 1 h at 4ºC. The tissue was then dehydrated through a series of solutions of increasing ethanol concentration, infiltrated with mixtures of propylene oxide and EPON resin, and embedded in 100% EPON resin. Sections were obtained to show tangential or radial views of the central retina, illustrating the photoreceptor mosaic or photoreceptors along their lengths, respectively. Tangential and radial views of the peripheral retina (circumferential growth zone) were also obtained from select juvenile and adult specimens. Sections, 1–2 μm thick, were stained with Richardson’s solution (1:1 mixture of 1% Azure II in dH2O and 1% Methylene blue in 1% NaB4O7) and photographed with an E-600 Nikon microscope equipped with a DXM-100 digital camera. The objective used was a Plan/Apo 60X/1.40 and the field of view was further amplified 1.5-2x with an optical tourette on the microscope. Thin (75 nm) sections were obtained, in parallel, to examine the ultrastructure of photoreceptors. Thin sections were collected on 200 μm copper grids, stained with 5% uranyl acetate in 50% ethanol, followed by 5% lead citrate, and viewed with a transmission electron microscope (JEOL). Representative images are based on examination of at least 6 specimens per species and developmental stage.

Immunohistology

Whole bodies of larvae were fixed (4% paraformaldehyde in 0.08 M PBS, pH 7.4) at 4 oC for at least 72 h. Following several rinses in 0.08 M PBS, the tissue was cryoprotected in sucrose solution (25% sucrose, 20% optimal cutting temperature [OCT] medium in 0.08 M PBS) and embedded in 100% OCT medium (Cedar Lane Laboratories). The resulting blocks were cryosectioned in 7–10 μm steps to reveal tangential or radial views of the eyes. Sections were deposited on poly-L-lysine coated slides and used for immunohistochemical detection of α-tubulin. This involved blocking the sections with a 1:20 solution of normal donkey serum: PBTA (PBTA: 0.5% bovine serum albumin in 0.08 M PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.1% sodium azide) overnight at 4 °C, followed by another overnight incubation in a PBTA solution containing mouse monoclonal antibody sc-32293 (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) against α-tubulin of avian origin (1:200). After several rinses in PBTA, sections were incubated in donkey antimouse Cy 3 antibody (1:200 in PBTA) (Jackson Immunoresearch) overnight at 4 °C. Parallel, control experiments were conducted without the primary or secondary antibodies and showed only minimal background fluorescence, as expected from the fixative31. Slides were mounted with 5% n‐propyl‐gallate in glycerol and photographed with the E-600 Nikon microscope equipped for Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) and fluorescence imaging.

Spatial analyses of cone topography

Digital micrographs of tangential sections from the central retina of larvae, each covering a 28 × 28 μm2 area, were analyzed with Photoshop (Adobe Systems) to count the number of near neighbours and extract the X-Y coordinates (centroids) of every cone in the field of view. Published micrographs from African clawed frog tadpole41, embryonic chicken42, and adult human4 were analyzed in the same way except that the tadpole area was 79 × 79 μm2. The coordinates were imported into a customized Matlab program that computed the Delauney tessellation of the field, from which the nearest neighbour distance of each individual cell was determined, as was their Voronoi domain area (i.e., the area surrounding each cell that encloses the territory closer to that cell than to any of the neighbours)43. Each analysis excluded “border cells”, i.e., those with uncertain nearest neighbour distances or Voronoi domain areas. In each case, the regularity index was defined as the mean divided by the standard deviation.

To assess whether the cone distributions analyzed had higher order (lattice-like) periodicity, a spatial auto-correlation analysis was carried out that examined the positioning of each cell with respect to all other cells across the mosaic. The Density Recovery Profile was derived from each autocorrelogram, providing a plot of the mean density of cells as a function of distance from each cell. The autocorrelogram permits the detection of higher order patterning and the Density Recovery Profile provides a measure of the exclusion zone surrounding each cell where other like-cells are less likely to be found than at further distances43.

Statistical analysis

One way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey HSD and Student-Newman-Keuls post-hoc tests were used to compare near-neighbour numbers between mosaics of different species at α = 0.05 level of significance.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper.

References

Ebrey, T. & Koutalos, Y. Vertebrate photoreceptors. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 20, 49–91 (2001).

Hárosi, F. I. Novales Flamarique, I. Functional significance of the taper of vertebrate cone photoreceptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 139, 159–187 (2012).

Bartel, P., Yoshimatsu, Y., Janiak, F. K. & Baden, T. Spectral inference reveals principal cone-integration rules of the zebrafish inner retina. Curr. Biol. 6, 5214–5226 (2021).

Curcio, C. A., Sloan, K. R., Kalina, R. E. & Hendrickson, A. E. Human photoreceptor topography. J. Comp. Neurol. 292, 497–523 (1990).

Sawides, L., de Castro, A. & Burns, S. A. The organization of the cone photoreceptor mosaic measured in the living human retina. Vis. Res. 132, 34–44 (2017).

Lyall, A. H. Cone arrangements in teleost retinae. Q. J. Microsc Sci. 98, 189–201 (1957).

Engstrom, K. Cone types and cone arrangements in teleost retinae. Acta Zool. 44, 179–243 (1963).

Frau, S., Novales Flamarique, I., Keeley, P. W., Reese, B. E. & Muñoz-Cueto, J. A. Straying from the flatfish retinal plan: cone photoreceptor patterning in the common sole (Solea solea) and the Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). J. Comp. Neurol. 528, 2283–2307 (2020).

Dunn, R. F. Studies on the retina of the gecko, Coleonyx variegatus. II the rectilinear visual cell mosaic. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 16, 672–684 (1966).

Loew, E. R., Govardovskii, V. I., Röhlich, P. & Szél, A. Microspectrophotometric and immunocytochemical identification of ultraviolet photoreceptors in geckos. Vis. Neurosci. 13, 247–256 (1996).

Stell, W. K. & Hárosi, F. I. Cone structure and visual pigment content in the retina of the goldfish. Vis. Res. 16, 647–657 (1976).

Downing, J. E. G., Djamgoz, M. B. A. & Bowmaker, J. K. Photoreceptors of a cyprinid fish, the roach: morphological and spectral characteristics. J. Comp. Physiol. A 159, 859–868 (1986).

Novales Flamarique, I. & Hawryshyn, C. W. The common white sucker (Catostomus commersoni): a fish with ultraviolet sensitivity that lacks polarization sensitivity. J. Comp. Physiol. A 182, 331–341 (1998).

Novales Flamarique, I. & Hárosi, F. I. Photoreceptors, visual pigments and ellipsosomes in the killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus: a microspectrophotometric and histological study. Vis. Neurosci. 17, 403–420 (2000).

Novales Flamarique, I. & Hárosi, F. I. Photoreceptor morphology and visual pigment content in the retina of the common white sucker (Catostomus commersoni). Biol. Bull. 193, 209–210 (1997).

Kunz, Y. W., Ennis, S. & Wise, C. Ontogeny of the photoreceptors in the embryonic retina of the viviparous guppy, Poecilia reticulata P. (Teleostei). Cell. Tissue Res. 230, 469–486 (1983).

Shand, J., Archer, M. A. & Collin, S. P. Ontogenetic changes in the cone photoreceptor mosaic in a fish, the black bream, Acanthopagrus butcheri. J. Comp. Neurol. 412, 203–217 (1999).

Shand, J., Archer, M. A. & Cleary, N. T. Retinal development of West Australian dhufish, Glaucosoma hebraicum. Vis. Neurosci. 18, 711–724 (2001).

Marchiafava P. L. Cell coupling in double cones of the fish retina. Proc. R. Soc. B 1243, 211–215 (1985).

Nishimura, Y., Smith, R. L. & Shimai, K. Junction-like structure appearing at apposing membranes in the double cone of chick retina. Cell. Tissue Res. 218, 113–116 (1981).

Günther, A. et al. Double cones and the diverse connectivity of photoreceptors and bipolar cells in an avian retina. J. Neurosci. 41, 5015–5028 .

Zou, J., Wang, X. & Wei, X. Crb apical polarity proteins maintain zebrafish retinal cone mosaics via intercellular binding of their extracellular domains. Dev. Cell 22, 1261–1274 (2012).

Hao, Q. et al. Crumbs proteins stabilize the cone mosaics of photoreceptors and improve vision in zebrafish. J. Gen. Genom. 48, 52–62 (2021).

Kram, Y. A., Mantey, S. & Corbo, J. C. Avian cone photoreceptors tile the retina as five independent, self-organizing mosaics. PLoS ONE 5, e8992 (2010).

French, A. S., Snyder, A. W. & Stavenga, D. G. Image degradation by an irregular retinal mosaic. Biol. Cybern 27, 229–233 (1977).

Brainard, D. H. Color and the cone mosaic. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 1, 519–546 (2015).

Eigenmann, C. H. & Shafer, G. D. The mosaic of single and twin cones in the retina of fishes. Am. Nat. 34, 109–118 (1900).

Larison, K. D. & Bremiller, R. Early onset of phenotype and cell patterning in the embryonic zebrafish retina. Development 109, 567–576 (1990).

Hoke, K. L., Evans, B. I. & Fernald, R. D. Remodeling of the cone photoreceptor mosaic during metamorphosis of flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus). Brain Behav. Evol. 68, 241–254 (2006).

Bolstad, K. Novales Flamarique, I. Photoreceptor distributions, visual pigments and the opsin repertoire of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus). Sci. Rep. 12, 8062 (2022).

Bolstad, K. Novales Flamarique, I. Chromatic organization of cone photoreceptors during eye migration of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus). J. Comp. Neurol. 531, 256–280 (2023).

Valen, R. et al. The two-step development of a duplex retina involves distinct events of cone and rod neurogenesis and differentiation. Dev. Biol. 416, 389–401 (2016).

Ahlbert, J. B. Ontogeny of double cones in the retina of perch fry (Perca fluviatilis. L., Teleostei). Acta Zool. 54, 241–254 (1973).

Branchek, T. & Bremiller, R. The development of photoreceptors in the zebrafish, Brachydario rerio. I structure. J. Comp. Neurol. 224, 107–115 (1984).

Schmitt, E. A. & Kunz, Y. W. Retinal morphogenesis in the rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. Brain Behav. Evol. 34, 48–64 (1989).

Schmitt, E. A. & Dowling, J. E. Early retinal development in the zebrafish, Danio rerio: light and electron microscopic analyses. J. Comp. Neurol. 404, 515–536 (1999).

Mader, M. M. & Cameron, D. A. Photoreceptor differentiation during retinal development, growth, and regeneration in a metamorphic vertebrate. J. Neurosci. 24, 11463–11472 (2004).

Allison, W. T. et al. Ontogeny of cone photoreceptor mosaics in zebrafish. J. Comp. Neurol. 518, 4182–4195 .

Morris, V. B. Time differences in the formation of the receptor types in the developing chick retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 151, 323–330 (1973).

Suzuki, S. et al. Cone photoreceptor types in zebrafish are generated by symmetric terminal divisions of dedicated precursors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 15109–15114 (2013).

Chang, W. S. & Harris, W. A. Sequential genesis and determination of cone and rod photoreceptors in Xenopus. J. Neurobiol. 35, 227–244 (1998).

Bruhn, S. L. & Cepko, C. L. Development of the pattern of photoreceptors in the chick retina. J. Neurosci. 16, 1430–1439 (1996).

Reese, B. E. & Keeley, P. W. Design principles and developmental mechanisms underlying retinal mosaics. Biol. Rev. 90, 854–876 (2015).

Bejarano-Escobar, R. et al. Eye development and retinal differentiation in an altricial fish species, the senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis, Kaup 1858). J. Exp. Zool. B 314, 580–605 (2010).

Pagh-Roehl, K., Wang, E. & Burnside, B. Posttranslational modifications of tubulin in teleost photoreceptors cytoskeletons. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 11, 593–610 (1991).

Sharkova, M., Aparicio, G., Mouzaaber, C., Zolessi, F. R. & Hocking, J. C. Photoreceptor calyceal processes accompany the developing outer segment, adopting a stable length despite a dynamic core. J. Cell. Sci. 137, jcs261721 (2024).

Salbreux, G., Barthel, L. K., Raymond, P. A. & Lubensky, D. K. Coupling mechanical deformations and planar cell polarity to create regular patterns in the zebrafish retina. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002618 (2012).

Nunley, H. et al. Defect patterns on the curved surface of fish retinae suggest a mechanism of cone mosaic formation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 16, e1008437 (2020).

Kunz, Y. W. Cone mosaic in a teleost retina: changes during light and dark adaptation. Experientia 36, 1371–1374 (1980).

Yoshimatsu, T., Schröder, C., Nevala, N. E., Berens, P. & Baden, T. Fovea-like photoreceptor specializations underlie single UV-cone driven prey capture in zebrafish. Neuron 107, 320–337 (2020).

Novales Flamarique, I. et al. Disrupted eye and head development in rainbow trout with reduced ultraviolet (SWS1) opsin expression. J. Comp. Neurol. 529, 3013–3031 (2021).

Kondrashev, S. L., Gnyubkina, V. P., Valentina, P. & Zueva, L. V. Structure and spectral sensitivity of photoreceptors of two anchovy species: Engraulis japonicus and Engraulis encrasicolus. Vis. Res. 68, 19–27 (2012).

Novales Flamarique, I. Swimming behaviour tunes fish polarization vision to double prey sighting distance. Sci. Rep. 9, 944 (2019).

Orger, M. B. & Baier, H. Channeling of red and green cone inputs to the zebrafish optomotor response. Vis. Neurosci. 22, 275–281 (2005).

Zukoshi, R. & Savelli, I. Novales Flamarique, I. Foraging performance of two fishes, the threespine stickleback and the Cumaná Guppy, under different light backgrounds. Vis. Res. 145, 31–38 (2018).

Evans, B. I., Hárosi, F. I. & Fernald, R. D. Photoreceptor spectral absorbance in larval and adult winter flounder. Vis. Neurosci. 10, 1065–1071 (1993).

Novales Flamarique, I. A novel function for the pineal organ in the control of swim depth in the Atlantic halibut larva. Naturwissenschaften 89, 163–166 (2002).

Bagariano, T. & Hunter, J. R. The visual feeding threshold and action spectrum of northern anchovy (Engraulis mordax) larvae. CalCOFI Rep. 24, 245–254 (1983).

Novales Flamarique, I. A vertebrate retina with segregated colour and polarization sensitivity. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20160058 (2016).

Savelli, I. & Novales Flamarique, I. Variation in opsin transcript expression explain intraretinal differences in spectral sensitivity of the northern anchovy. Vis. Neurosci. 35, e005.

Peichl, L. Diversity of mammalian photoreceptor properties: adaptations to habitat and lifestyle? Anat. Rec. 287, 1001–1012 (2005).

Sajdak, B. et al. Noninvasive imaging of the thirteen-lined ground squirrel photoreceptor mosaic. Vis. Neurosci. 33, e003 (2016).

Choi, J., Joisher, H. N. V., Gill, H. K., Lin, L. & Cepko, C. Characterization of the development of the high-acuity area of the chick retina. Dev. Biol. 511, 39–52 (2024).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Origins of direction selectivity in the primate retina. Nat. Comm. 13, 2862 (2022).

Tommasini, D., Yoshimatsu, T., Baden, T. & Shekhar, L. Comparative transcriptomic insights into the evolutionary origin of the tetrapod double cone. BioRxiv (2025).

Collin, S. P., Davies, W. L., Hart, N. S. & Hunt, D. M. The evolution of early vertebrate photoreceptors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 364, 2925–2940 (2009).

Appudurai, A. M., Hart, N. S., Zurr, I. & Collin, S. P. Morphology, characterization and distribution of retinal photoreceptors in the South American (Lepidosiren paradoxa) and spotted African (Protopterus dolloi) lungfishes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 4, 78 (2016).

Locket, N. A. Retinal structure in Latimeria chalumnae. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 493–521 (1973).

Silman, A. J., Beach, A. K., Dahlin, D. A. & Loew, E. Photoreceptors and visual pigments in the retina of the fully anadromous green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostrus) and the potadromous pallid sturgeon (Scaphirhynchus albus). J. Comp. Physiol. A 191, 799–811 (2005).

Baden, T. From water to land: evolution of photoreceptor circuits for vision in air. PLoS Biol. 22, e3002422 .

Rowe, M. P., Engheta, N., Easter, S. S. & Pugh, E. N. Graded-index model of a fish double cone exhibits differential polarization sensitivity. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 11, 55–70 .

Labhart, T. Can invertebrates see the e-vector of polarization as a separate modality of light? J. Exp. Biol. 219, 3844–3856 (2016).

McManamon, P. F. et al. Optical phased array technology. Proc. IEEE 84, 268–298 (1996).

Lind, O., Chavez, J. & Kelber, A. The contributions of single and double cones to spectral sensitivity in budgerigars during changing light conditions. J. Comp. Physiol. A 200, 197–207 (2014).

Baden, T. Ancestral photoreceptor diversity as the basis of visual behaviour. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1–13 (2024).

Hagen, J. F. D., Roberts, N. S. & Johnston, R. J. Jr The evolutionary history and spectral tuning of vertebrate visual opsins. Dev. Biol. 493, 40–66 (2023).

Rowe, D. M. & Denton, E. J. The physical basis for reflective communication between fish, with special reference to the horse mackerel, Trachurus trachurus. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 352, 531–549 .

Novales Flamarique, I., Mueller, G. A., Cheng, C. L. & Figiel, C. R. Communication using eye roll reflective signalling. Proc. R. Soc. B 274, 877–882 (2007).

Guggiana-Nilo, D. A. & Engert, F. Properties of the visible light phototaxis and UV avoidance behaviors in the larval zebrafish. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 160.

Savelli, I., Novales Flamarique, I., Iwanicki, T. & Taylor, J. S. Parallel opsin switches in multiple cone types in the starry flounder retina: tuning visual pigment composition for a demersal life style. Sci. Rep. 8, 4763.

Musilova, Z. & Cortesi, F. The evolution of the green-light-sensitive visual opsin genes (RH2) in teleost fishes. Vis. Res. 206, 108204 (2023).

Collins, B. A. & MacNichol, E. F. Jr. Morphological observations and microspectrophotometric data from photoreceptors in the retina of the sea raven, Hemitropterus americanus. Biol. Bull. 167, 437–444 (1984)

Novales Flamarique, I., Bergstrom, C., Cheng, C. L. & Reimchen, T. E. Role of the iridescent eye in stickleback female mate choice. J. Exp. Biol. 216, 2806–2812 (2013).

Siebeck, U. E., Parker, A. N., Sprenger, D., Mäthger, L. M. & Wallis, G. A species of reef fish that uses ultraviolet patterns for covert face recognition. Curr. Biol. 210, 407–410 (2010).

Cheng, C. L., Novales Flamarique, I., Härosi, F. I., Rickers-Haunerland, J. & haunerland, N. H. Photoreceptor layer of salmonid fishes: transformation and loss of single cones in juvenile fish. J. Comp. Neurol. 495, 213–235 .

Cheng, C. L. & Novales Flamarique, I. Chromatic organization of cone photoreceptors in the retina of rainbow trout: single cones irreversibly switch from UV (SWS1) to blue (SWS2) light sensitive opsin during natural development. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 4123–4135 (2007).

Carleton, K. L. et al. Visual sensitivities tuned by heterochronic shifts in Opsin gene expression. BMC Biol. 6, 22 (2008).

Loew, E. R. & Wahl, C. M. A short-wavelength sensitive cone mechanism in juvenile yellow perch, Perca flavescens. Vis. Res. 31, 353–360 (1991).

Novales Flamarique, I. & Hawryshyn, C. W. No evidence of polarization sensitivity in freshwater sunfish from multi-unit optic nerve recordings. Vis. Res. 37, 967–973 (1997).

Dearry, A. & Barlow, R. B. Circadian rhythms in the green sunfish retina. J. Gen. Physiol. 89, 745–770 (1987).

Novales Flamarique, I. & Wachowiak, M. Functional segregation of retinal ganglion cell projections to the optic tectum of rainbow trout. J. Neurophysiol. 114, 2703–2717 (2015).

Lu, K. et al. Role of short-wave-sensitive 1 (sws1) in cone development and first feeding in larval zebrafish. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 49, 801–813 (2023).

Novales Flamarique, I. Diminished foraging performance of a mutant zebrafish with reduced population of ultraviolet cones. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. 283, 2016058 (2016).

Alavarez-Delfin, K. et al. Tbx2b is required for ultraviolet photoreceptor cell specification during zebrafish retinal development. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 2023–2028 (2009).

Zhang, R. et al. Retinal development in mandarinfish Siniperca chuatsi and morphological analysis of the photoreceptor layer. J. Fish. Biol. 95, 903–917 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Tristan Robbins and Tony Andrychuk (Vancouver Island Trout hatchery), Swarajpal Randhawa and Briony Campbell (Golden Eagle Sablefish hatchery), David García Valcarce (Spanish Institute of Oceanography), Marie Laure Bégout (IFREMER, L’Houmeau), Ruth Frey and Deborah Stenkamp (University of Idaho), Carling Gerlinsky and Dolph Schluter (University of British Columbia), and previous staff at Scotian Halibut Ltd for help will collections of specimens. We also thank Brent Gowen (University of Victoria) for assistance with electron microscopy. This research was funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grants RGPIN-2018-05722 and RGPAS-2018-522696 to I.N.F.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.N.F. conceived the study and carried out the electron microscopy; L.A.G. and I.N.F. performed the histology, analyzed results and drafted the figures; I.N.F. wrote the manuscript, L.A.G. commented on it, and both authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Novales Flamarique, I., Grebinsky, L.A. Single cones give rise to multi-cone types in the retinas of fishes. Sci Rep 15, 7823 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91987-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91987-w