Abstract

As intelligent cockpits rapidly evolve towards “proactive natural interaction,” traditional rule-based user behavior inference methods are facing scalability, generalization, and accuracy bottlenecks, leading to the development and deployment of functions oriented towards pseudo-demands. Effectively capturing and representing the hidden associative knowledge in intelligent cockpits can enhance the system’s understanding of user behavior and environmental contexts, thereby precisely discerning real user needs. In this context, knowledge graphs (KGs) have emerged as an effective tool, enabling the retrieval and organization of vast amounts of information within interconnected and interpretable structures. However, rapidly and flexibly generating domain-specific KGs still poses significant challenges. To address this, this paper introduces a novel knowledge graph construction (KGC) model, GLM-TripleGen, dedicated to analyzing the states and behaviors within intelligent cockpits. This model aims to precisely mine the latent relationships between cockpit state factors and behavioral sequences, effectively addressing key challenges such as the ambiguity in entity recognition and the complexity of relationship extraction within cockpit data. To enhance the adaptability of GLM-TripleGen to the intelligent cockpit domain, this paper constructs an instruction-following dataset based on vehicle states and in-cockpit interaction behaviors, containing a large number of prompt texts paired with corresponding triple labels, to support model fine-tuning. During the fine-tuning process, the Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) method is employed to effectively optimize model parameters, significantly reducing training costs. Extensive experiments demonstrate that GLM-TripleGen outperforms existing state-of-the-art KGC methods, accurately generating normalized cockpit triple units. Furthermore, GLM-TripleGen exhibits exceptional robustness and generalization ability, handling various unknown entities and relationships with minimal generalization processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As intelligent cockpits swiftly transition from “passive functional responses” to “proactive natural interaction”1, the functionalities within the cockpit continue to evolve, increasing in complexity. This evolution leads to increasingly diverse behavioral patterns within the cockpit, with the relationships between actions being more concealed. Traditional cockpit development, which utilizes rule-oriented scenario descriptions and intent reasoning, suffers from limited scalability, weak generalization capabilities, and restricted accuracy2,3,4. These issues often prevent the cockpit systems from adapting to new or unknown user behaviors and environmental changes, making it difficult to discern the true needs of drivers and passengers, thus affecting the overall system performance and user experience. In contrast, the development of intelligent cockpits driven by big data analytics of driver behaviors, by deeply exploring the spatiotemporal causal relationships between vehicle states and driver behavior sequences, effectively captures and represents hidden associative knowledge within the cockpit, thereby accurately depicting real user needs5,6. Insights into sparse associative data within the cockpit provide essential, high-quality support for downstream tasks such as behavior analysis, intent prediction, and personalized recommendations5,7,8,9,10. However, the original cockpit data are vast and complex, with intricate relationships that are not easily discernible, making the extraction of high-value information directly from them still a challenge.

KGs, as a powerful method for structured knowledge representation, systematically integrate and analyze cockpit data, effectively uncovering complex associations and behavioral patterns hidden within the data. Currently, KGs are extensively applied in fields such as information extraction11, recommendation systems12,13,14, natural language question answering15,16, and search engine optimization17. KGs utilize the triple form (entity 1, relationship, entity 2) to represent knowledge, revealing the relationships between entities. Essentially, they form a vast structured semantic network, designed to store and represent large-scale information18. Constructing cockpit KGs not only enables the systematic unveiling of complex relationships within cockpit data, helping developers better understand behavior patterns and potential needs within the cockpit, but also, through techniques19,20 such as graph vectorization or graph embedding, transforms the structured information in the KGs into low-dimensional vector representations. These representations can then provide accurate factual knowledge for downstream cockpit tasks, further improving task accuracy.

The key task in constructing KGs is to extract valuable information from semi-structured or unstructured data sources within specific or open domains, and express this information in a formalized triple format, thereby building the corresponding semantic network. Early methods21,22 of KGC typically employed specific rules or clustering techniques to extract information, or used pipeline models23,24 to sequentially identify entities and predict relationships between them. With the significant advances in deep learning within fields such as natural language processing (NLP), KGC techniques have seen substantial enhancement and support. This is primarily reflected in the use of deep learning models to effectively handle critical tasks such as named entity recognition25,26 and relationship extraction27,28, significantly improving the automation and accuracy of KGC. Furthermore, to effectively reduce redundancy and errors in processing, end-to-end deep learning models, such as those based on the Transformer architecture29, can simultaneously identify entities and their interrelationships in text29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, enhancing the synergy and accuracy of information extraction. Additionally, Open Information Extraction (OpenIE)35,40,41,42 enhances the depth and breadth of KGC by automatically identifying and extracting relationships and entities from a wide range of unstructured public data.

However, despite the many advantages brought by deep learning, these models often require large amounts of annotated data for training43, which can be difficult and costly to obtain, especially in specialized or data-scarce domains. One of the main reasons why the public application of KGs in the cockpit domain is not widespread is the lack of relevant data. Generative large language models (LLMs), with their exceptional semantic understanding and strong generalization capabilities, can maintain high performance in limited data environments. This reduces the need for domain-specific adaptations and effectively compensates for the lack of information in data-scarce areas42,44,45,46. This provides important support for the rapid construction, accuracy improvement, and dynamic updating of KGs, greatly expanding the construction approaches for cockpit KGs.

Therefore, this paper proposes a novel KGC model, GLM-TripleGen, for analyzing cockpit data and extracting normalized triple units. Unlike existing methods, GLM-TripleGen is the first to apply a LLM in the domain of cockpit KGC. The model leverages the powerful semantic understanding and generalization capabilities of LLMs, and fine-tunes with a small amount of domain-specific data to enhance its adaptability to specific cockpit environments. This enables efficient identification of cockpit-related entities and the generation of reasonable relationship descriptions. To ensure the model’s inference output aligns with the actual cockpit situations, a high-quality cockpit instruction-following dataset was constructed based on original data collected from actual vehicles, which was used for model fine-tuning. During fine-tuning, an adapter-based approach was employed to optimize model parameters, significantly reducing training costs. Furthermore, the innovation of the GLM-TripleGen model lies in its effective integration of multi-source heterogeneous information from cockpit data, including driver behavior, vehicle states, and environmental perception data, to construct comprehensive and accurate KGs.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

This paper constructs a novel cockpit instruction-following dataset. This dataset contains a large number of interpretable prompt texts and triple labels. The prompt texts reflect real driver behaviors and vehicle state factors, while the triple labels present hidden associative knowledge between vehicle states and behavior sequences in a structured manner. The dataset combines the general capabilities of LLMs with the prior knowledge of human experts. By accessing the GPT-4 model via the OpenAI official chat completion API, the dataset enables batch generation of triple labels, offering high consistency and interpretability.

-

The paper innovatively proposes a KGC model for intelligent cockpits, named GLM-TripleGen. This model comprises three main components: textual data encoding, an LLM backbone, and structured decoding, which specialized for cockpit KGC. The GLM-TripleGen model is fine-tuned on the cockpit instruction-following dataset, utilizing adapter methods to efficiently optimize model parameters. This approach not only reduces training costs but also effectively addresses key challenges such as ambiguity in entity recognition and complexity in relationship extraction within cockpit data.

-

Extensive experimental results on the specialized cockpit instruction-following dataset demonstrate that GLM-TripleGen surpasses existing state-of-the-art KGC methods. It can accurately generate normalized cockpit triple units, exhibiting exceptional performance in extracting and constructing structured knowledge relevant to the cockpit environment. Furthermore, numerous experiments on public information extraction datasets show that GLM-TripleGen can handle various unknown entity relationships with minimal generalization processing, displaying outstanding robustness and generalization capabilities.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: First, the “Related works” section summarizes the state-of-the-art in KGC and the latest advancements in using large models for KGC. Next, the “Problem definition” section defines the research problems addressed in this paper. This is followed by the “GPT-assisted instruction-following dataset construction” section, which details the construction process of the cockpit instruction-following dataset based on the GPT-4 model and human expert prior knowledge. The “Methodology” section then introduces the methodological model architecture and describes the process of fine-tuning LLMs to enhance their ability to construct cockpit KGs. Subsequently, the “Experiments” section presents and analyzes the experimental results and provides visualizations of the KG. Finally, the “Conclusion” section summarizes the study and proposes future research directions.

Related works

Intelligent cockpit and knowledge graph

With the rapid development of intelligent cockpit technology, cockpit functionalities continue to evolve, and cockpit data is becoming increasingly complex, encompassing a vast amount of unstructured and semi-structured information, including sensor data, user behavior records, and external environmental information1. Processing and analyzing the large volume of unstructured data generated by the cockpit forms the foundation for downstream tasks such as driver state analysis, behavior analysis, intent prediction, and personalized recommendations5,7,8,9,10.

Traditional rule-driven data response methods typically rely on a set of predefined and fixed rules, resulting in singular or limited linear mapping relationships. For example, Chang et al.2 proposed a simple rule where the system automatically activates the vehicle’s warning lights when signs of drowsiness or fatigue are detected in the driver, thereby enhancing driving safety. Similarly, PATEO Corporation3,4 has developed a scene-aware dynamic adaptation technology that intelligently recommends corresponding services based on the current context, such as suggesting navigation and seat adjustments during boarding, recommending music playback during commutes, and remotely activating the air conditioning when leaving the office after work. However, this rule-based approach often fails to fully leverage contextual information and struggles to effectively mine and utilize the deeper, latent connections between data.

In contrast, KGs can flexibly adapt to and represent various types of data relationships and attributes, transforming the latent associations in cockpit data into explicit semantic networks, thereby significantly enhancing the structured and dimensional interconnectivity of the data47. Currently, KGs have seen preliminary applications in the automotive sector, primarily focusing on anomaly detection and fault diagnosis, such as engine fault diagnosis and intelligent prediction48,49. For instance, Tang et al.48 and Xu et al.49 have constructed KGs in the realm of automotive engine faults, deeply exploring common issues between devices and guiding engine fault diagnosis and repair from both data and knowledge perspectives. This approach helps address challenges such as the lack of experience among repair personnel and insufficient quantitative factual evidence during engine maintenance.

Additionally, Sun et al.5 proposed the idea of building KGs from collected user, vehicle, and environmental data to establish user-centered intent prediction models and dialogue scenarios. Sheng et al.50 pointed out that introducing KGs in intelligent cockpits can not only meet user needs in specific contexts but also provide an enhanced user experience beyond expectations. Yang et al.6 designed a KG-driven task-oriented dialogue model using in-vehicle dialogue data to improve the response quality of intelligent cockpit dialogue systems. Thus, it is evident that constructing KGs can transform scattered, unstructured raw cockpit data into structured, interpretable graphical databases, facilitating in-depth exploration and analysis of driver behaviors and vehicle states.

Knowledge graph construction

In the early stages of KGC, researchers primarily relied on extracting patterned knowledge from textual data to create KGs. Early milestones in this field, such as TextRunner21 and KnowItAll22, used specific rules or clustering methods to extract information. However, these methods often lacked sufficient background knowledge, leading to an inability to effectively distinguish or aggregate different knowledge entities. Moreover, traditional rule-based information extraction systems required extensive feature engineering and additional expert knowledge. To address these issues, researchers proposed constructing knowledge structures by dividing the tasks into subtasks. A classic example23,24 involves first identifying and linking entities, followed by coreference resolution to unify different expressions referring to the same entity, and finally extracting the relationships between entities. This approach builds KGs in a systematic logical order, but each subtask may require different techniques and algorithms, making the overall process complex and time-consuming.

In recent years, breakthroughs in deep learning within fields such as NLP have injected new momentum into KGC techniques, significantly advancing their development. Wei et al.37 proposed a novel cascade binary tagging framework named CasRel, which prioritizes the extraction of head entities and then simultaneously extracts relationships and tail entities. Wang et al.38 introduced a one-stage joint extraction model, TPLinker, which transforms the joint extraction task into a tag pair linking problem and introduced a novel handshake tagging scheme. Sui et al.39 proposed a non-autoregressive parallel decoding method, which can directly output the final predicted set of triples in one go. Additionally, Nayak et al.30 introduced a decoding method based on the Pointer Network, achieving efficient and accurate extraction and recognition of relational triples from text. Zeng et al.36 proposed an end-to-end joint extraction model based on the Copy Mechanism, named CopyRE, within a Sequence-to-Sequence (Seq2Seq) learning framework, although the entity prediction part of this model was not stable enough. To address this issue, Zeng et al.35 later introduced a multitask learning framework equipped with the Copy Mechanism, CopyMTL, allowing the model to predict multi-label entities. However, models based on the Copy Mechanism and using Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) as encoders/decoders struggle to capture long-distance dependencies in text. Ye et al.29 proposed a contrastive triple extraction model based on the generative Transformer, which enhances the credibility of the generated triples. Lu et al.34 proposed a unified text-to-structure generative information extraction model. Despite these methods achieving good results and generating high-quality KGs, they are often limited by predefined sets of entities and relationships or depend on specific ontologies and usually struggle to handle ambiguous contextual information.

With the rapid development of generative LLMs, society is undergoing an unprecedented transformation. Through training on vast amounts of text data, these models demonstrate a profound understanding of human language and powerful generative capabilities, particularly in key technical fields such as NLP, data analysis, machine translation, and content generation51. Agrawal et al.52 and Wei et al.53 point out that pre-trained language models possess extensive and robust general knowledge, enabling them to leverage advanced NLP techniques to identify and extract complex patterns and relationships within textual data, thereby distilling valuable information54,55,56. This not only showcases their immense potential in handling structured and unstructured data but also provides strong support for the in-depth analysis and understanding of large-scale text collections.

Trajanoska et al.57 created a pipeline for automatically generating KGs from raw text, suggesting that using LLM models can improve the accuracy of KGC from unstructured text. Ashok and Lipton58 proposed PromptNER, an algorithm for few-shot and cross-domain named entity recognition, which generates potential entity lists by prompting LLMs. Xu et al.59 designed an automated annotation process that includes schema design, information extraction, and KG completion using LLMs and prompt engineering. Carta et al.60 proposed a zero-shot general KGC scheme by iteratively prompting GPT-3.5. Wang et al.61 pre-trained language models on a series of task-agnostic corpora to generate structure from text, further fine-tuning on specific tasks to enhance training effectiveness.

Although the aforementioned prompt-based KGC methods using LLMs are fast, efficient, and do not require updating model parameters, their effectiveness is limited by the generalization capabilities of pre-trained models and the design of prompt templates62. When handling complex and multi-layered relationships, these methods often fall short and struggle to accurately adapt to the data patterns and semantic requirements of specific domains. To address these challenges, this paper leverages the structured knowledge extraction capabilities of large models and proposes a novel KGC model, GLM-TripleGen. By constructing a cockpit instruction-following dataset and generating an adapter, the model can effectively analyze the latent relationships between driver behaviors and vehicle state factors, thereby capturing both explicit and implicit knowledge within cockpit data. This approach resolves the challenges of information extraction and understanding in scenarios with sparse cockpit-associated data.

Problem definition

During driving, occupants inevitably interact with the vehicle. This paper employs event tracking technology to collect a large amount of human-vehicle interaction behavior data, combined with extensive vehicle state data from the CAN bus, resulting in a vast yet internally disconnected dataset of cockpit data. To enhance the value and usability of this data, we propose a model named GLM-TripleGen, aimed at revealing the implicit relationships and semantic connections between the data, thereby transforming the complex raw data into a logical and interpretable knowledge network of vehicle states and user behavior sequences. This network supports deeper analyses and applications, such as scene understanding, intent prediction, and personalized service recommendations in downstream tasks.

The core task of KGC is to generate structured triple units. This process primarily involves identifying behavioral and state entities from pre-processed textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{T}}}\), as well as inferring the logical relationships that connect these entities, thereby constructing meaningful knowledge relationships. In this work, the input for KGC consists of formal, interpretable textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{T}}}\) derived from the original cockpit data, along with a segment of instructional text \({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{I}}}\) designed to guide the LLM. The output is structured triple data \({\varvec{{G}}}\):

where \({F}_{GLM}(\cdot )\) represents the triple construction function. The instructional text \({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{I}}}\) contains the task goal \({\varvec{{x}}}_{\varvec{{goal}}}\), input description \({\varvec{{x}}}_{\varvec{{in}}}\), and output instruction \({\varvec{{x}}}_{\varvec{{out}}}\):

Textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{T}}}\) is represented as a collection of the current vehicle states \({\varvec{{s}}}_{n_{obs}}\) and a directed sequence of behaviors \({\varvec{{h}}}_{(n_{obs}-j):n_{obs}}\):

where the current vehicle states \({\varvec{{s}}}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) is represented as the vehicle state during the \(n_{obs}\)-th behavior \({\varvec{{h}}}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) in the i-th driving interval:

The current vehicle states \({\varvec{{s}}}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) includes, but is not limited to, the current vehicle speed \({v}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\), gear \({g}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\), key switch states \({k}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\), engine states \({e}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\), environment temperature \({t}_{env,n_{obs}}^{i}\), air conditioning switch states \({a}_{o/f,n_{obs}}^{i}\), air conditioning temperature \({a}_{temp,n_{obs}}^{i}\), and air conditioning mode \({a}_{mode,n_{obs}}^{i}\), among others.

The behavior sequence \({\varvec{{h}}}_{(n_{obs}-j):n_{obs}}^{i}\) records the temporal attributes \({h}_{t,n_{obs}}^{i}\), general behavior attributes \({h}_{g,n_{obs}}^{i}\), and detailed behavior attributes \({h}_{d,n_{obs}}^{i}\) of the driver’s current behavior \({\varvec{{h}}}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) and the previous j behaviors:

The triple output \({\varvec{{G}}}\) represents a set of key information extracted from the input textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\), consisting of m structured triples, formally expressed as:

where \(u_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}=(h_{k,n_{obs}}^{i},r_{k,n_{obs}}^{i},t_{k,n_{obs}}^{i})\) is defined as the k-th triple element in the set \({\varvec{{G}}}\), represented as comprising two entities \(h_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}\) (head entity) and \(t_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}\) (tail entity), along with a relation \(r_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}\) characterizing the relationship between these two entities.

It is noteworthy that a vast amount of raw behavioral data is collected over several different driving intervals. Additionally, because real driving behavior sequences are not uniformly distributed over time, this paper utilizes an event-driven behavior recording method, whereby one driving interval comprises \(N_{evt}\) actions.

The problem is defined as follows: By integrating multi-dimensional cockpit data, a uniform, standardized textual structure centered around driver behavior is formed, which is then concatenated with carefully designed instructional text. Using GPT-4, triple labels are generated to construct a cockpit instruction-following dataset. Building upon this foundation, the dataset is used to fine-tune a LLM and incorporate adapters to automate the extraction and construction of triple information from textual data, thereby constructing a KG, as shown in Fig. 1.

GPT-assisted instruction-following dataset construction

Due to the scarcity of cockpit data, publicly available proprietary datasets for constructing cockpit KGs are virtually non-existent. This section aims to construct a cockpit instruction-following dataset based on the GPT model and human knowledge through two main parts: textual data preprocessing and triple labels generation, as shown in Fig. 2. This dataset can be used to fine-tune the GLM-TripleGen model, enabling it to automatically extract and construct triples from textual data.

Textual data preprocessing

Cockpit data is foundational for constructing KGs in the cockpit domain. However, raw cockpit data is often disorganized and cryptic, with relationships between data points being obscure and difficult to discern, which complicates the extraction of useful information. Therefore, appropriate and effective data processing is essential for building a cockpit instruction-following dataset, significantly enhancing the data’s quality and usability. This paper standardizes data formats through attribute definition, enriches data dimensions via data augmentation, and removes redundant information through noise cleaning. These preprocessing steps substantially improve data quality and consistency, thereby maximizing the extraction and utilization of information.

Data attribute definition

The raw data is organized into collections consisting of numerous key-value pairs, where each key corresponds to a specific data item. These data items typically appear in formats such as numbers, strings, or arrays, which are not easily interpretable and thus inconvenient for direct input into LLMs. Therefore, this paper initially defines the attributes of the raw data to achieve a standardized representation.

-

(1)

State attribute definition In state data, information such as gear position \({g}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\), engine states \({e}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\), and in-vehicle air conditioning states (including air conditioning switch \({a}_{o/f,n_{obs}}^{i}\) and mode \({a}_{mode,n_{obs}}^{i}\), etc.) is typically discrete, predefined, and finite, making it suitable for direct use in representing KG nodes:

$$\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{aligned} g_{n_{obs}}^{i}&\in \{\text {Park, Reverse, Neutral, Drive,} \ldots , \text {Brake}\} \\ e_{n_{obs}}^{i}&\in \{\text {Shutdown, Dragging, Running}\} \\ a_{o/f,n_{obs}}^{i}&\in \{\text {ON, OFF}\} \\ a_{mode,n_{obs}}^{i}&\in \{\text {Front Vent, Bi-Level, Floor Vent,} \ldots , \text {Defrost}\} \end{aligned} \right. \end{aligned}$$(7)However, data such as vehicle speed \({v}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) and temperature (\({t}_{env,n_{obs}}^{i}\), \({a}_{temp,n_{obs}}^{i}\), etc.) are continuous and variable, possessing inherent complexity and unpredictability. If each possible value were to be treated as an independent entity, it could lead to issues such as an explosion of nodes in the KG. Therefore, this study employs a discretization approach, whereby continuous variables are divided into finite intervals, and each interval is assigned a specific grade label, thereby mapping continuous variables to finite discrete variables.

This paper employs a series of statistical analysis methods to ensure the scientific validity and practicality of the interval division. By analyzing the overall distribution of the data, observing the frequency distribution characteristics, and integrating practical application demands and expert experience, an initial interval division strategy is determined. Subsequently, each interval undergoes descriptive statistical analysis, such as calculating means, medians, and standard deviations, to assess the representativeness and consistency of the intervals. Finally, the boundaries of the intervals are adjusted as needed to optimize the division and ensure the rationality of the intervals.

Taking vehicle speed \({v}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) (measured in kilometers per hour, km/h) as an example, the discretization process simplifies the representation of data, thereby effectively controlling the complexity of the KG:

$$\begin{aligned} v_{n_{obs}}^{i} = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \text {Idle Vehicle Speed} & \text {if } v = 0 \\ \text {Ultra-Low Speed} & \text {if } v \in (0, 10] \\ \text {Low Speed} & \text {if } v \in (10, 20] \\ \text {Medium-Low Vehicle Speed} & \text {if } v \in (20, 40] \\ \text {Medium Vehicle Speed} & \text {if } v \in (40, 60] \\ \text {Medium-High Vehicle Speed} & \text {if } v \in (60, 90] \\ \text {High Vehicle Speed} & \text {if } v \in (90, 120] \\ \text {Ultra-High Vehicle Speed} & \text {if } v \in (120, +\infty ) \\ \text {Default} & \text {else.} \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(8)Additionally, another typical example is the temperature attribute, which includes environment temperature, cockpit temperature, air conditioning temperature, etc. This work aims to discretize these into a finite number of nodes to facilitate the construction of the KG. Based on the distribution of the data and expert experience, this paper applies a more detailed division for the middle temperature range, while adopting a broader division strategy for low and high temperature areas. This is because the human body is more sensitive to subtle changes within the moderate temperature range (18 to 28 degrees Celsius); slight fluctuations in temperature can significantly affect the comfort and operational performance of the occupants. Thus, a finer division of the middle temperature interval can more accurately reflect human perception differences of temperature, enhancing the scientific validity and practicality of the KG. Conversely, in the extreme low and high temperature regions, where human perception changes are relatively gradual or already beyond the body’s comfort range, a broader division simplifies data processing and enhances model efficiency.

-

(2)

Behavior attribute definition This study decomposes complex behaviors into two levels: general attributes and detailed attributes. General attributes represent the basic category or type of behavior, while detailed attributes provide additional information about specific contexts or conditions.

For example, in the processed behavior “Stop playing music, applicable to Bluetooth music,” “Stop playing music” can be considered a general attribute \(h_{g,n_{obs}}^{i}\), describing a basic action. In contrast, “applicable to Bluetooth music” serves as a detailed attribute \(h_{d,n_{obs}}^{i}\), providing a specific application context, that is, the music being stopped is played via Bluetooth. Similarly, in the interaction “Adjust the air conditioning blowing level, set to level 3,” “Adjust the air conditioning blowing level” and “level 3” are regarded as the general attribute \(h_{g,n_{obs}'}^{i}\) and detailed attribute \(h_{d,n_{obs}'}^{i}\), respectively. This hierarchical division not only helps clarify the hierarchical relationships of behaviors but also makes the parsing and understanding of behaviors more systematic and modular.

Furthermore, considering that in KGs, time nodes precise to the second can lead to an explosion of nodes and a dilution of their referential value, this study divides time into intervals or periods \(t_{perd,n_{obs}}^{i}\). Additionally, it includes information such as the day of the week on which the behavior occurred \(t_{week,n_{obs}}^{i}\) and the duration since the driver boarded \(t_{dura,n_{obs}}^{i}\). This duration \(t_{dura,n_{obs}}^{i}\) is a key indicator for measuring driver behavior and car usage habits. Analyzing the relationship between the duration since the driver boarded and other behavior attributes is of significant value for understanding driver behavior and predicting travel needs.

$$\begin{aligned} h_{t,n_{obs}}^{i}=\{t_{perd,n_{obs}}^{i},t_{week,n_{obs}}^{i},t_{dura,n_{obs}}^{i}\} \end{aligned}$$(9)where \(t_{dura,n_{obs}}^{i} = \{\text {Getting ready to use the vehicle, Within 5 mins, 5 to 10 mins, 10-20 mins,} \ldots \}\), in this context, “Getting ready to use the vehicle” refers to a brief period right after boarding the vehicle, such as within 100 seconds. Such a subdivision helps in precisely tracking the driver’s behavior patterns at different stages, providing accurate data support for optimizing in-vehicle system designs and enhancing the driving experience.

Table 1 Examples of state attributes converted to behavior attributes.

Data augmentation

Due to limitations in technology and other factors, the collected state data and behavior data often fail to fully reflect the complexities of the driving environment. That is, the existing behavior attributes and state attributes are not sufficient to comprehensively characterize cockpit behaviors and their associated states. Therefore, in the study of cockpit data, the interconversion between states and behaviors becomes particularly important.

-

(1)

Conversion from state attributes to behavior attributes The existing behavior attributes primarily reflect the driver’s use of the cockpit’s infotainment systems (such as radio, music, calls, navigation, voice commands, and settings) and adjustments to the air conditioning, but they lack capture of behaviors like seat adjustments, door operations, and window controls. However, these data can be obtained from state attributes. For instance, the state of the seat slide motor can represent the behavior of adjusting the seat forwards or backwards, and the state of the door can indicate the driver’s action of opening or closing the door, as detailed in Table 1. By converting state attributes into behavior attributes, it is possible to supplement and refine the definition of behavior attributes, thereby more comprehensively capturing and understanding the driver’s behavior patterns and the vehicle’s usage:

$$\begin{aligned} {\varvec{{h}}}_{conv}^{i} = f_{conv}^{s \rightarrow h}({\varvec{{s}}}_{h,conv}^{i}) \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(f_{conv}^{s \rightarrow h}(\cdot )\) represents the function for converting states to behaviors, and \({\varvec{{h}}}_{conv}^{i}\) denotes the behavior data derived from the specific state data \({\varvec{{s}}}_{h,conv}^{i}\).

-

(2)

Conversion from behavior attributes to state attributes Similar to the conversion from state to behavior attributes, the existing state attributes are primarily limited to the vehicle’s driving states and body states, lacking descriptions of the states of in-cockpit equipment, which can be gleaned from behavior attributes. For example, actions such as starting or continuing music playback can indicate that the music state is ’on’, while stopping or pausing music playback or the end of the driving trip can represent the music state being ’off’. Common state attributes that can be derived from such conversions also include radio, telephone, navigation, and driving scenarios. By analyzing the driver’s behavior data, the usage states of these devices can be inferred, thereby enriching the state attributes:

$$\begin{aligned} {\varvec{{s}}}_{conv}^{i} = f_{conv}^{h \rightarrow s}({\varvec{{h}}}_{s,conv}^{i}) \end{aligned}$$(11)where \(f_{conv}^{h \rightarrow s}(\cdot )\) represents the function that converts behavior to state attributes, while \({\varvec{{s}}}_{conv}^{i}\) denotes the state attributes derived from the specific behavior attributes \({\varvec{{h}}}_{s,conv}^{i}\).

By mutually converting specific behavior attributes and state attributes, it is possible to effectively fill the gaps in existing attribute definitions. Additionally, this reciprocal conversion and comprehensive utilization of data greatly enrich the understanding of the cockpit environment, enabling the extraction of meaningful behavior and state patterns from originally scattered and isolated data points.

Data denoising

This study employs rule-based constraints for data deduplication and compression, effectively reducing data redundancy. This method allows for the extraction of the most crucial information from a vast amount of raw data, ensuring the accuracy and practicality of the data.

The main rules include the following three categories:

-

Redundancy removal This refers to deleting duplicate data under the same data point and excluding invalid or low-value data. Specific rules are as follows:

-

If the same behavior is repeated continuously for 5 seconds, only the first instance is retained.

-

When a user continuously adjusts the in-vehicle air conditioning temperature or mode, only the last setting is retained.

-

Exclude behavior categories with a frequency lower than 5%.

-

- ...

-

-

Game theory rules (conflict resolution) When logical conflicts, violations of facts, or time misalignment occur between successive operations, the operation that best fits the actual situation should be chosen. For example, if a driver’s action (e.g., turning on the air conditioning) is incorrectly recorded as occurring after the next event (e.g., adjusting the air conditioning blowing level), the timestamp should be adjusted or aligned to resolve the logical contradiction and time misalignment, ensuring the correct sequence of operations.

-

Forward filling For missing data, use subsequent values or infer missing values based on surrounding data to ensure the continuity and integrity of the data flow. Specific rules are as follows:

-

If the environmental temperature value at a certain point is invalid (e.g., out of range), the subsequent valid data can be used to fill in the missing value.

-

If speed data is missing at a certain point, use the speed data from previous and subsequent time points to perform interpolation and fill in the missing value.

-

...

-

-

Redundancy removal This refers to deleting duplicate data under the same data point and excluding invalid or low-value data. Specific rules are as follows:

-

If the same behavior is repeated continuously for 5 seconds, only the first instance is retained.

-

When a user continuously adjusts the in-vehicle air conditioning temperature or mode, only the last setting is retained.

-

Exclude behavior categories with a frequency lower than 5%.

-

...

-

-

Game Theory Rules (Conflict Resolution): When logical conflicts, violations of facts, or time misalignment occur between successive operations, the operation that best fits the actual situation should be chosen. For example, if a driver’s action (e.g., turning on the air conditioning) is incorrectly recorded as occurring after the next event (e.g., adjusting the air conditioning blowing level), the timestamp should be adjusted or aligned to resolve the logical contradiction and time misalignment, ensuring the correct sequence of operations.

-

Forward Filling: For missing data, use subsequent values or infer missing values based on surrounding data to ensure the continuity and integrity of the data flow. Specific rules are as follows:

-

If the environmental temperature value at a certain point is invalid (e.g., out of range), the subsequent valid data can be used to fill in the missing value.

-

If speed data is missing at a certain point, use the speed data from previous and subsequent time points to perform interpolation and fill in the missing value.

-

...

-

Additionally, with over 30 existing state attributes, comprehensively summarizing all state attributes for each behavior description would make the text overly cumbersome. The presence of numerous state items unrelated to the behavior would increase the understanding difficulty and processing burden for large models. This study employs state reduction techniques, retaining only those state attributes that are closely related to specific behaviors. This not only reduces data complexity but also minimizes the interference of irrelevant state information on model performance, thereby more accurately capturing the key correlations between behaviors and states. Effective state reduction should consider the characteristics of the behavior and contextual needs, choosing to analyze state attributes that are highly relevant to it, thus ensuring the accuracy and practicality of the analysis results.

where \(f_{match}^{s \downarrow }(\cdot )\) represents the state matching function.

Triple labels generation

Inspired by the recent success of the GPT model in text annotation tasks63,64, this paper proposes the construction of cockpit instruction-following dataset using ChatGPT/GPT-4 and prompt engineering. This approach primarily leverages prompt engineering to bridge the gap between the model’s general capabilities and the specific needs of application scenarios. Through carefully designed instructional text, the large model’s task analysis and reasoning capabilities are effectively stimulated, enabling the model to capture and represent the latent associative knowledge within the cockpit effectively within the given contextual information.

In the previous section, this paper utilized the CAN bus monitoring functions \(F_{dect}(\cdot )\) and cockpit event tracking functions \(F_{track}(\cdot )\) from the tool library to extract vehicle state data and cockpit interaction behavior data, respectively. Through processing these data, the interaction behavior information \({\varvec{{h}}}_{(n_{obs}-j):n_{obs}}^{i}\) of the driver within the cockpit and specific vehicle state factors \({\varvec{{s}}}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) are embedded into fixed sentence formats to form textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\) that represents the context of the current interaction behavior.

To generate high-quality cockpit triple labels, this section aims to meticulously design instructional text \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{I}}}}=\{{\varvec{{x}}}_{goal},{\varvec{{x}}}_{in},{\varvec{{x}}}_{out}\}\) that matches the corresponding textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\) . Here, \({\varvec{{x}}}_{goal}\) represents the task goal, which is used to guide the direction and logic of the LLM’s processing. The input description \({\varvec{{x}}}_{in}\) is used to briefly explain what specific information will be input to the LLM, essentially providing a concise introduction to the textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\) to help the model understand the main content and inherent logic of the text. The output instruction \({\varvec{{x}}}_{out}\) includes constraints and expectations for the LLM’s outputs, encompassing restrictions on the range of entity extraction, guiding the model’s reasoning direction, and specifying the type and format of triples to be generated. These components collectively define how the system should respond and operate during user interaction, ensuring the accuracy and consistency of information during the interaction process. Subsequently, the instructional text \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{I}}}}\) and textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\) are concatenated to form the input for constructing the cockpit instruction-following dataset.

To efficiently and batch-generate triple labels, this paper utilizes the official chat completion API to interact with the GPT-4 model by submitting a series of messages. Each message is assigned a specific role, allowing for responses that are consistent with the dialogue thread. The commonly used three roles are system, user, and assistant, corresponding to the instructional text \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{I}}}}\), textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\), and triple output \({\varvec{{G}}}\) of this paper, respectively. This step includes two objectives:

-

Appropriate entity representation, aimed at accurately identifying and understanding the information contained within text mentioning entities, ensuring that the model can extract key data points from complex contexts.

-

Rational relationship and triple descriptions, aimed at precisely constructing and articulating the relationships between entities, facilitating the generation of logically coherent and structurally clear triples.

The triple labels generated need to undergo validation before they can become part of the dataset. Classic methods for assessing the quality of information generated by artificial intelligence involve human evaluators who judge and annotate the system’s outputs. In this study, human expertise plays a highly effective role in assessing the quality and correctness of the generated triples. Additionally, human evaluators can supplement the completeness of the triples, such as identifying missing or incomplete entities. During the manual annotation process, triples are marked as correct based on two factors: (i) the description of the entity is accurate, intuitive, and relevant to the input text, and (ii) it must accurately represent a real and reasonable relationship, meaning the triple conforms to real-world logic. Some representative examples are as follows:

-

Triple (Adjust the front passenger’s seat heating level, in the environment of, Temperature in the range (− 5,0]); Evaluation: incorrect. This fails to meet criterion (i), as the description of the entity is ambiguous. In the input textual data, information on temperature includes environment temperature, cockpit temperature, and air conditioning set temperature. However, in this triple, the specific attribution of the temperature is not clearly expressed.

-

Triple (No Direct Sunlight, facilitates, Adjust the air conditioning blowing mode); Evaluation: incorrect. This does not satisfy criterion (ii), as the relationship between “No Direct Sunlight” and “Adjust the air conditioning blowing mode” is not directly relevant or logically strong. This description fails to clearly demonstrate a reasonable causal relationship between the two.

-

Triple (Drivers Seat Heating OFF, leads to, Adjust the air conditioning blowing mode); Evaluation: incorrect. This fails to meet criterion (ii), as similarly, there is no causality between “Driver’s Seat Heating OFF” and “Adjust the air conditioning blowing mode.” The expressed relationship lacks correspondence in real-life situations and is not supported by practical logic.

Building on the steps described, this paper utilized the GPT-4 model to generate over 26K pairs of cockpit data texts and triple labels, facilitating the construction of the cockpit instruction-following dataset as shown in Figure 3. Within the triple units \(u_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}\), entities \(h_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}\) and \(t_{k,n_{obs}}^{i}\) should be strongly related to the current vehicle states \({\varvec{{s}}}_{n_{obs}}^{i}\) and directed behavior sequences \({\varvec{{h}}}_{(n_{obs}-j):n_{obs}}^{i}\). The relationships between entities should be inferred based on contextual information, such as examples in the output instructions \({\varvec{{x}}}_{out}\), descriptions in the textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\), and expansions inspired by GPT-4’s reasoning. This dataset accurately records the driver’s operational behaviors in different state scenarios and structured hidden knowledge, which can be used to fine-tune the GLM-TripleGen model, thus aiding in the construction of the cockpit KG.

Methodology

Model architecture

The GLM-TripleGen model architecture consists of three main components: textual data encoding, lightweight fine-tuning of the LLM backbone adapter, and structured decoding of triple labels, as shown in Figure 4. Initially, through the textual data encoding layer, instructional text \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{I}}}}\) and textual data \({\varvec{{X}}}_{{\varvec{{T}}}}\) are transformed into a format that can be processed by the LLM. Subsequently, by integrating adapters into the LLM backbone, GLM-TripleGen is effectively tailored to the cockpit triple extraction task. Finally, by incorporating rules or templates in the decoding process, the model’s intermediate representations are converted into normalized triple outputs.

-

(1)

Textual data encoding The input to GLM-TripleGen consists of information such as vehicle state factors and cockpit behavior sequences, referred to as instructional-text data \(({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{I}}} \oplus {\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{T}}})\). Initially, a text tokenizer \(f_{\varphi }(\cdot )\) is used to transform the text input into a series of text tokens that the model can understand, known as input tokens \({\varvec{{I}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\):

$$\begin{aligned} {\varvec{{I}}}_{\varvec{{L}}} = f_{\varphi }({\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{I}}} \oplus {\varvec{{X}}}_{\varvec{{T}}}) \end{aligned}$$(13) -

(2)

Lightweight fine-tuning of LLM backbone adapter This paper employs LoRA as an adapter to perform lightweight fine-tuning on the pretrained language model. The core idea of LoRA fine-tuning is to maintain the complexity and universality of the LLM while introducing low-rank matrix updates to effectively modify and optimize key parameters of the model. This method allows for localized adjustments to specific layers of the model without the need to retrain the entire network, thereby rapidly adapting to new tasks or data environments while reducing the consumption of training resources.

As shown in Fig. 5, this paper utilizes ChatGLM3-6B65 as the model backbone, which is composed of multiple transformer layers and possesses excellent instruction-following capabilities. In this work, LoRA is integrated into each transformer’s linear layers, specifically including the Group Query Attention (GQA) layer and the Feed-Forward Network (FFN) layer. The input tokens \({\varvec{{I}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\) are first processed through the GQA layer, where LoRA serves as an additional module integrated into each attention matrix, namely the query matrix \({\varvec{{Q}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\), key matrix \({\varvec{{K}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\), and value matrix \({\varvec{{V}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\). LoRA modifies these matrices using a down-projection matrix \({\varvec{{A}}}\) and an up-projection matrix \({\varvec{{B}}}\). During training, the input and output dimensions of the GQA layer remain unchanged, and the linear transformation matrices for each attention matrix are frozen. Only the newly added down-projection matrix \({\varvec{{A}}}\) and the up-projection matrix \({\varvec{{B}}}\) are involved in training, where \({\varvec{{A}}}\) is initialized using a random Gaussian distribution and \({\varvec{{B}}}\) using a zero matrix. The computation of the entire GQA mechanism is as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} & {GroupQueryAttn}({\varvec{{Q}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}},{\varvec{{K}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}},{\varvec{{V}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}})={Concat}(head_{1},\ldots ,head_{h}){\varvec{{W}}}^{\varvec{{o}}} \end{aligned}$$(14)$$\begin{aligned} & \begin{aligned} head_h =&Attn({\varvec{{Q}}}_{\varvec{{L}}},{\varvec{{K}}}_{\varvec{{L}}},{\varvec{{V}}}_{\varvec{{L}}})=softmax(\frac{{\varvec{{Q}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}{\varvec{{K}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}){\varvec{{V}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\\&\text {where}\, {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} {\varvec{{Q}}}_{\varvec{{L}}} = ({\varvec{{W}}}_{h}^{q}+{\varvec{{B}}}_{h}^{q}{\varvec{{A}}}_{h}^{q}){\varvec{{Y}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\\ {\varvec{{K}}}_{\varvec{{L}}} = ({\varvec{{W}}}_{h}^{k}+{\varvec{{B}}}_{h}^{k}{\varvec{{A}}}_{h}^{k}){\varvec{{Y}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\\ {\varvec{{V}}}_{\varvec{{L}}} = ({\varvec{{W}}}_{h}^{v}+{\varvec{{B}}}_{h}^{v}{\varvec{{A}}}_{h}^{v}){\varvec{{Y}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\end{array}\right. } \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(15)where \({\varvec{{W}}}_{h}^{q}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},d_k)}\), \({\varvec{{W}}}_{h}^{k}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},d_k)}\) and \({\varvec{{W}}}_{h}^{v}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},d_v)}\) are the linear transformation matrices of query matrix \({\varvec{{Q}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\), key matrix \({\varvec{{K}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\) and value matrix \({\varvec{{V}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}\) for each attention head \(\textit{head}_{h}\). \({\varvec{{A}}}_{h}^{q}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},r)}\), \({\varvec{{A}}}_{h}^{k}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},r)}\) and \({\varvec{{A}}}_{h}^{v}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},r)}\) are the down-projection matrices. \({\varvec{{B}}}_{h}^{q}\in \mathbb {R}^{(r,d_k)}\), \({\varvec{{B}}}_{h}^{k}\in \mathbb {R}^{(r,d_k)}\) and \({\varvec{{B}}}_{h}^{v}\in \mathbb {R}^{(r,d_v)}\) are the up-projection matrices, with \(r\ll min(d_{model},d_{k/v})\). \({\varvec{{W}}}^{\varvec{{o}}}\in \mathbb {R}^{(hd_v,d_{model})}\) is the output transformation matrix.

Subsequently, a residual connection and Root Mean Square (RMS) Normalization operation are applied to obtain \({\varvec{{S}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\):

$$\begin{aligned} {\varvec{{S}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}=RMSNorm({\varvec{{I}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}+GroupQueryAttn({\varvec{{Q}}}_{\varvec{{L}}},{\varvec{{K}}}_{\varvec{{L}}},{\varvec{{V}}}_{\varvec{{L}}})) \end{aligned}$$(16)Next, \({\varvec{{S}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\) passes through the FFN layer \(\textit{rFFN}(\cdot )\), which consists of two fully connected layers and a SwiGLU activation function. LoRA is integrated into these two fully connected layers using the same training method as described above. Specifically, the weight matrices of the two fully connected layers are frozen, and only the down-projection matrix \({\varvec{{A}}}\) and up-projection matrix \({\varvec{{B}}}\) are trained. Following another residual connection and RMS Normalization operation, the output of this transformation layer \({\widetilde{{\varvec{{I}}}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\) is obtained:

$$\begin{aligned} & rFFN({\varvec{{S}}}_{\varvec{{L}}})=({\varvec{{W}}}_2^f+{\varvec{{B}}}_2^f{\varvec{{A}}}_2^f)\cdot SwiGLU(({\varvec{{W}}}_1^f+{\varvec{{B}}}_1^f{\varvec{{A}}}_1^f){\varvec{{S}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}) \end{aligned}$$(17)$$\begin{aligned} & {\widetilde{{\varvec{{I}}}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}=RMSNorm({\varvec{{S}}}_{\varvec{{L}}}+rFFN({\varvec{{S}}}_{\varvec{{L}}})) \end{aligned}$$(18)where \({\varvec{{W}}}_{1}^{f}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},d_{ff})}\) is the weight matrix of the first fully connected layer and \({\varvec{{W}}}_{2}^{f}\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{ff},d_{model})}\) is the weight matrix of the second fully connected layer. \({\varvec{{A}}}_1^f\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{model},r)}\) and \({\varvec{{A}}}_2^f\in \mathbb {R}^{(d_{ff},r)}\) are the down-projection matrices. \({\varvec{{B}}}_1^f\in \mathbb {R}^{(r,d_{ff})}\) and \({\varvec{{B}}}_2^f\in \mathbb {R}^{(r,d_{model})}\) are the up-projection matrices, with \(r\ll min(d_{model},d_{ff})\).

\({\widetilde{{\varvec{{I}}}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\) will then be used as the input token for the next transformer layer, repeating the above operations. Finally, after passing through multiple transformer layers enhanced with LoRA, the generated intermediate representation tokens from the LLM backbone are obtained, denoted as \({\varvec{{T}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\):

$$\begin{aligned} {\varvec{{T}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}=\sum _{L=1}^{n}({Transfomer}({\varvec{{I}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}))^{L} \end{aligned}$$(19)where \({\varvec{{T}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\) contains all reasoning information required for the current task.

-

(3)

Triple labels structured decoding After obtaining the intermediate representation tokens \({\varvec{{T}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}\) generated by the LLM backbone, the ChatGLM3-6B’s default text detokenizer \(f_{\tau }(\cdot )\) is used to decode them into human-readable language. This decoding process first extracts relevant entities and relationships from the intermediate representation, then combines this information into triple form according to a predefined template, ensuring the generated triple labels are both accurate and consistent. The output triples \({\varvec{{G}}}\) are structured as a series of data entries containing two entities and a relationship representing the connection between them. This structured decoding method enables the model to accurately identify the head entity, relationship, and tail entity, using contextual information for logical alignment, thereby producing triples rich in semantic information. The entire structured decoding process is represented as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} {\varvec{{G}}}=f_{\tau }({\varvec{{T}}}_{{\varvec{{L}}}}) \end{aligned}$$(20)By converting complex textual data into a structured form that is easier to process and analyze, the system can perform information retrieval, relationship extraction, and knowledge inference more effectively, thereby enhancing the data’s utility and value. Additionally, by structuring the data, the system can more easily identify patterns and trends within the data, supporting the capability to handle complex queries and improving the analytical precision of semantic search.

Model training

The training of GLM-TripleGen is divided into two phases: (1) Pre-training, which aims to train the model on a large-scale corpus to capture the fundamental structure and semantics of language, thereby enhancing the model’s general capabilities; (2) Fine-tuning, which aims to help the model learn how to generate logical and factual knowledge representations based on specific input conditions, improving GLM-TripleGen’s specialized ability to construct KGs in the cockpit domain.

Pre-training The pre-training in this study is primarily based on the BookCorpus45 and the Wikipedia dataset used by BERT66. Additionally, the pre-training corpus encompasses documents from various sources, including web pages, books, and research papers. The mixed use of these documents aims to enhance the diversity of the training data. The pre-training data covers a broad range of topics and is not specifically designed for constructing cockpit domain KGs. Through this approach, the study ensures that the model has a broad knowledge base and strong generalization capabilities. This ensures that when learning new tasks, the model can effectively integrate new information while maintaining the stability of its existing knowledge structure.

Fine-tuning The fine-tuning of GLM-TripleGen is conducted using the cockpit instruction-following dataset constructed for this study, to facilitate the task of constructing cockpit KGs. Given that the output of GLM-TripleGen is in natural language, cross-entropy loss \(\Gamma (\theta )\) is used to supervise the model’s inferential outputs. The definition of cross-entropy loss \(\Gamma (\theta )\) is as follows:

where \(\theta\) represents the trainable parameters, the optimization of these parameters will directly influence the model’s performance on specific tasks.

Experiments

This section conducts an extensive experimental evaluation of GLM-TripleGen on a proprietary cockpit instruction-following dataset and publicly available information extraction datasets, providing a series of qualitative analyses and quantitative results to more comprehensively understand GLM-TripleGen’s performance and capabilities across various cockpit scenarios.

Experimental setup

-

(1)

Implementation details During the pre-training phase, GLM-TripleGen was trained for one epoch on relevant datasets with a batch size of 128, distributed across 8 A100 (40G) GPUs. In the fine-tuning phase, to ensure good generalization performance during training and effectively reduce overfitting, this study employed cross-validation to analyze the training and validation loss curves. The entire cockpit instruction-following dataset was divided into a training set and a test set, with a ratio of 4:1. During the training process, 5-fold cross-validation was used on the training data to ensure stable performance of the model across different data subsets. The model was ultimately evaluated on an independent test set to ensure a fair comparison with other methods.Additionally, to avoid overfitting during fine-tuning, the AdamW optimizer was used to update the loss function, with an initial learning rate set to 5e-5. To effectively adjust the learning rate during training, a cosine annealing strategy was employed, which gradually reduces the learning rate according to a cosine function to help the model approach the global optimum more smoothly. Given the model’s large parameter size, the LoRA fine-tuning method was adopted to optimize the parameter size and reduce training costs. The rank of the dimensionality reduction projection matrix was set to 8, and the scaling factor was set to 16. The target modules were the linear layers within the LLM backbone. Fine-tuning was conducted on each GPU with a batch size of 2 per batch over 5 epochs. The entire fine-tuning process was completed on 4 L20 (48G) GPUs.

-

(2)

Evaluation metrics To quantitatively assess the performance of GLM-TripleGen in constructing cockpit KGs, this study employs two distinct types of evaluation metrics: conventional metrics incorporating human expert prior knowledge and metrics based on NLP.

Firstly, to ensure a fair comparison with other methods, this study employs conventional evaluation metrics that incorporate human expert prior knowledge, including accuracy, recall, and the F1 score. Based on the classic entries of a confusion matrix, the model-generated triples that accurately reflect the relationships between valid entities are designated as true positives (TP). Triples incorrectly generated by the model are labeled as false positives (FP). False negatives (FN) refer to the correct triples that exist but were not identified and generated by the model:

$$\begin{aligned} & P=\frac{TP}{TP+FP} \end{aligned}$$(22)$$\begin{aligned} & R=\frac{TP}{TP+FN} \end{aligned}$$(23)$$\begin{aligned} & F_{1}=\frac{2 \cdot P \cdot R}{P+R} \end{aligned}$$(24)Secondly, to measure the consistency of the model outputs with human standards, this study also introduces evaluation metrics based on NLP, including BLEU-4, ROUGE-N, and ROUGE-L. These metrics are primarily used to assess the quality of text generated by the model, particularly in terms of grammatical coherence and content accuracy.

-

BLEU-4 This metric is widely used in language generation tasks, primarily by assessing the quality of the text through the similarity between the n-grams of the generated text and the n-grams in the reference text:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {BLEU-4} = BP \cdot e^{\left( \sum _{n=1}^{N} \omega _n \log (p_n) \right) } \end{aligned}$$(25)where BP stands for brevity penalty (BP). \(p_n\) represents the precision of matches for each n-gram, from 1 to N, where N is typically set to 4. \(\omega _n\) indicates the weight given to the precision of each n-gram, and in BLEU-4, these weights are usually distributed equally.

-

ROUGE-N This metric emphasizes the extent to which the generated text covers key information found in the reference text, reflecting the completeness of the generated content. ROUGE-N focuses on recall, which is the frequency with which n-grams from the reference text appear in the generated text:

$$\begin{aligned} \text {ROUGE-N} = \frac{c_{n\text {-gram}}^{\text {gen}}}{c_{n\text {-gram}}^{\text {ref}}} \end{aligned}$$(26)where \(c_{n\text {-gram}}^{\text {gen}}\) represents the number of specific n-grams in the generated text that match those in the reference text, and \(c_{n\text {-gram}}^{\text {ref}}\) is the total number of those n-grams in the reference text.

-

ROUGE-L This metric evaluates the coherence and logical order of information based on the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS). Unlike relying on exact n-gram matches, it assesses the similarity between the generated text and the reference text by identifying the longest sequence of elements that appear in both texts, regardless of their order.

$$\begin{aligned} \text {ROUGE-L} = \frac{(1 + \lambda ^2) \cdot P_{\text {LCS}} \cdot R_{\text {LCS}}}{\lambda ^2 P_{\text {LCS}} + R_{\text {LCS}}} \end{aligned}$$(27)where \(P_{\text {LCS}}\) represents the proportion of the LCS relative to the length of the generated text; \(R_{\text {LCS}}\) represents the proportion of the LCS relative to the length of the reference text (i.e., the standard triple text in the test set); \(\lambda\) represents the harmonic balancing factor, which is typically set to 1.

-

Comparison with baseline methods

To demonstrate the superior performance of GLM-TripleGen in constructing cockpit KGs, this paper compares the GLM-TripleGen model with GPT-3.567, Deepstruct61, and Vicuna1.568,69 models on the cockpit instruction-following dataset. The results, as shown in Table 2, indicate that in the specific domain of the cockpits, GLM-TripleGen performs exceptionally well, achieving an accuracy rate of up to 95.86% in the triple generation task, which is 3.51% higher than the second-best method. It also reaches a recall rate of 93.67%, far surpassing other methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in extracting cockpit triples. Moreover, in terms of content generation, GLM-TripleGen achieves outstanding results with BLEU-4 and ROUGE-L scores of 93.56% and 93.20%, respectively, significantly outperforming the other models.

Additionally, to demonstrate the generalization capability of the GLM-TripleGen model, this paper conducts tests using public datasets. Table 3 presents the testing results of GLM-TripleGen on the WebNLG70 and NYT datasets65, along with performance comparisons with other methods29,30,35,36,37,38,39. The results show that GLM-TripleGen also performs excellently on public datasets. In the two public datasets, it achieved accuracy rates of 94.2% and 93.7%, and recall rates of 93.6% and 93.3%, respectively, surpassing existing state-of-the-art KGC models. In comparisons with these models, GLM-TripleGen benefits from the extensive knowledge and understanding capabilities of LLMs. This allows it to utilize its general reasoning ability to automatically extract and generate semantically rich relationships from textual data, even when the subject-predicate-object structures are not completely intact, greatly enhancing the accuracy of triple construction.

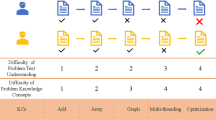

Ablation study

The ablation study aims to explore the impact of removing or modifying specific model components on the performance of the model. This paper validates the effectiveness and optimized design of the method through ablation studies. In the GLM-TripleGen model, two modules are particularly critical: text data preprocessing and text instruction construction. This study focuses on analyzing the specific impacts of these two modules on the performance of the GLM-TripleGen model.

Ablation of the textual data preprocessing module This module is responsible for cleaning and standardizing raw text data to meet the requirements for model processing. In the experimental setup for ablation of this module, the study directly inputs unprocessed textual data into the model to evaluate the impact of preprocessing steps on data quality and the accuracy of final outputs.

Ablation of the text instruction construction module This module is significant for building specific text instructions based on task requirements, guiding the model to effectively extract information. In the experiment where this module is removed, the study eliminates the use of custom instructions, and the model must rely solely on its fundamental understanding capabilities to perform the task.

After each ablation experiment, this paper compares the outputs of the model without the specific module to those of the complete model to assess the importance of each module. As shown in Table 4, the removal of any module leads to a significant

decrease in performance, confirming the critical role and necessity of these two modules. Reducing steps in the cockpit textual data preprocessing leads to a substantial decrease in the accuracy of information extraction. Specifically, the presence of noise and inconsistencies in unprocessed text greatly increases the difficulty for the model to identify key information, thereby affecting the quality and completeness of the generated triples. Moreover, the experimental results also show that without the text instruction construction module, the model’s outputs become more generalized and lack specificity, especially when required to perform complex queries or data extractions based on specific instructions. The absence of clear guidance makes it difficult for the model to focus on task-relevant information, leading to the generation of broader and more ambiguous results.

In a comprehensive comparison, although the removal of both modules significantly weakens the model’s performance, the absence of textual data preprocessing has an especially severe impact on the results. This underscores the importance of high-quality input data in ensuring efficient and accurate information extraction in the construction of cockpit domain KGs.

Interpretability analysis

Interpretability analysis is crucial for understanding the model’s decision-making process and improving the model’s trustworthiness in specific tasks. This paper primarily studies the interpretability of the model from two aspects: training and inference, which are the main methods of interpretability analysis71, as shown in Figure 6. The training strategy enhances the model’s interpretability by influencing weight distribution and revealing feature interactions within the model, while in the inference process, techniques such as Chain of Thought (CoT) reasoning provide structured and interpretable outputs. Table 5 shows the impact of adjusting fine-tuning parameters and removing CoT prompting techniques on model performance.

-

(1)

LoRA fine-tuning strategy The LIMA model72 demonstrated that foundational knowledge and generalization capabilities are established during pre-training, and targeted fine-tuning enhances interpretability by refining rather than overhauling core knowledge. In this study, we use the LoRA approach to build a dedicated adapter for KGC. Since LoRA fine-tuning focuses only on adjusting specific layers and feature representations, it reduces the model’s parameter space, making the model’s behavior more traceable. By analyzing the parameters adjusted by LoRA and the learned feature representations, a clearer understanding can be gained of how the model constructs the cockpit KG based on input data, particularly in how it handles relationships between different entities and the reasoning process, thus improving the model’s interpretability.

-

(2)

CoT prompting technique CoT reasoning has become a powerful technique for enhancing the interpretability of reasoning tasks71. The CoT prompting method significantly improves the performance of LLMs when handling complex tasks73. Although LLMs excel at generating human-like responses, they lack transparency in the reasoning process, making it difficult for users to assess the credibility of the model’s responses, especially for tasks that require detailed reasoning74. To mitigate the opacity of the LLM reasoning process, this study enhances the prompts with comprehensible content, which can include domain-specific insights, contextual information, and step-by-step reasoning chains. During the LLM’s response process, the model reveals its decision-making process in reasoning, thus improving the interpretability of the prediction results.

Specifically, the LLM is defined as \(f_\theta\), and the input prompt is defined as \(X=\{x_c, y_c, x_g\}\), where \(x_c\) and \(y_c\) are example question-answer pairs provided for in-context learning, and \(x_g\) represents the question to be solved. The model’s output can be expressed as \(y_g = \arg \max _Y p_\theta (Y | x_c, y_c, x_g)\). However, this approach does not provide transparency in the reasoning process. In the CoT prompting method introduced in this paper, in addition to the question-answer pairs, an additional reasoning explanation \(e_c\) is introduced. The structured reasoning chain provided by \(e_c\) helps the model understand how to derive the correct answer from the input question. Given the input, the model will output not only \(y_g\) but also the generated explanation \(e_g\):

$$\begin{aligned} {e_g, y_g = \arg \max _Y p_\theta (Y | x_c, e_c, y_c, x_g).} \end{aligned}$$(28)This approach incorporates the reasoning chain into the model’s input, making the model’s output not only the answer but also the reasoning process that supports it, providing higher transparency and interpretability.

-

(3)

Interactive explanation Interactive explanation, as a method of interpretability analysis71, differs from traditional static interpretability approaches by providing more flexible and dynamic forms of explanation, as shown in Fig. 6. Interactive explanation allows developers or users to obtain customized explanations of the model through specific instructions or queries. The model can provide specific and precise explanations based on the user’s input and the particular context, rather than offering fixed, predefined results.

Complexity analysis

This paper comprehensively considers both the model’s performance and architecture, evaluating its complexity from two aspects.

Base model This paper uses ChatGLM3-6B as the backbone model, which is built on multiple Transformer layers and has a large number of parameters. The complexity mainly lies in the computation overhead of the attention mechanism and feedforward network in each Transformer layer. Due to the depth and the large number of parameters in the Transformer layers, the model’s complexity increases significantly in terms of computation and memory usage.

Adapter This paper uses the LoRA fine-tuning strategy to construct an adapter specifically for cockpit KGC. LoRA adapts the model by introducing low-rank matrices. Compared to full-parameter fine-tuning, LoRA only involves updating the low-rank matrices when adjusting parameters, significantly reducing the number of parameters that need to be optimized during training. The low-rank matrices help reduce the model’s complexity by limiting the matrix’s expressive power, meaning that LoRA can flexibly adjust the model’s complexity by controlling the rank and scaling factor of the adapter. Specifically, the rank

of the adapter determines the upper limit of the model’s representational capability. Smaller rank values effectively reduce the model’s complexity, while the scaling factor affects the magnitude of the model weight adjustments. By appropriately selecting the rank and scaling factor, model complexity can be controlled without sacrificing performance. In this paper, the rank of the dimensionality reduction projection matrix is set to 8, and the scaling factor is set to 16. As shown in Table 5, experimental tests indicate that a rank of 8 strikes a balance between model complexity and expressive capability, and a scaling factor of 16 helps control the adjustment magnitude of the low-rank matrix, making the model more stable during fine-tuning.

Through thoughtful design and optimization, this paper effectively controls the complexity of the model while ensuring performance, especially with the fine-tuning strategy of the adapter, which significantly reduces the computational burden during training and inference.

In-context learning versus fine-tuning

In-context learning and fine-tuning are two popular strategies for guiding LLMs to perform specific tasks. Although the fine-tuning approach in this study has shown excellent performance, it has also sparked discussions about whether in-context learning could achieve similar results. To explore this, the paper designed a contextual learning experiment. In this setup, the model is provided with sample prompts about cockpit information and expected triple outputs, testing its performance without direct parameter adjustments. The outcomes are then compared with those from the fine-tuning approach.

As shown in Table 6, the fine-tuning strategy significantly outperforms the in-context learning strategy across all metrics. This is primarily because fine-tuning, by directly optimizing the model’s internal parameters, is better able to adapt to the specific linguistic patterns and data structures of the cockpit domain. Although in-context learning offers a certain level of flexibility without substantial modifications to the model, its performance is limited by the model’s current knowledge and understanding capabilities. Furthermore, the limited context observation window restricts its effectiveness in handling specialized and complex domain information.

This experiment demonstrates that although in-context learning does not rely on extensive resources and can quickly adapt to new environments, fine-tuning is clearly more effective for tasks that require deep customization and highly precise semantic understanding, such as extracting triples in the cockpit domain.

Visualization & qualitative analysis

To visually demonstrate the construction process and practical value of the cockpit KG, Figure 7 provides an interactive example from a specific driving scenario. This example reveals the interactive behaviors taken by the driver in a particular context and the vehicle states at that time, extracting key information in the form of triples. This showcases the model’s clear understanding of these specific interaction scenarios, effectively revealing the inherent logic of complex interactions. Specifically, GLM-TripleGen is deployed on the cloud, where it can receive real-time vehicle data from the vehicle terminal,

perform inference, generate new triples, and dynamically update the existing KGs. Through detailed examples, it is observable how the system accurately extracts key information from complex interaction data and converts it into structured triples, which is central to KGC. Each triple closely captures the main elements of the driving scenario, thus providing a clear framework for understanding and analyzing driving behaviors.

After successfully identifying entities and extracting relationships, this study imports the generated cockpit triples into a Neo4j database for triple data storage and knowledge visualization, thereby constructing cockpit domain KGs. As shown in Figure 8, the KG primarily displays high-frequency entities and relationships related to the in-vehicle air conditioning system. In the graph, deep blue represents action entities, light blue represents state entities, and the size of the nodes indicates the frequency of occurrence of the entities.

Conclusion