Abstract

Urban expansion and changes in land use/land cover (LULC) have intensified in recent decades due to human activity, influencing ecological and developmental landscapes. This study investigated historical and projected LULC changes and urban growth patterns in the districts of Multan and Sargodha, Pakistan, using Landsat satellite imagery, cloud computing, and predictive modelling from 1990 to 2030. The analysis of satellite images was grouped into four time periods (1990–2000, 2000–2010, 2010–2020, and 2020–2030). The Google Earth Engine cloud-based platform facilitated the classification of Landsat 5 ETM (1990, 2000, and 2010) and Landsat 8 OLI (2020) images using the Random Forest model. A simulation model integrating Cellular Automata and an Artificial Neural Network Multilayer Perceptron in the MOLUSCE plugin of QGIS was employed to forecast urban growth to 2030. The resulting maps showed consistently high accuracy levels exceeding 92% for both districts across all time periods. The analysis revealed that Multan’s built-up area increased from 240.56 km2 (6.58%) in 1990 to 440.30 km2 (12.04%) in 2020, while Sargodha experienced more dramatic growth from 730.91 km2 (12.69%) to 1,029.07 km2 (17.83%). Vegetation cover remained dominant but showed significant variations, particularly in peri-urban areas. By 2030, Multan’s urban area is projected to stabilize at 433.22 km2, primarily expanding in the southeastern direction. Sargodha is expected to reach 1,404.97 km2, showing more balanced multi-directional growth toward the northeast and north. The study presents an effective analytical method integrating cloud processing, GIS, and change simulation modeling to evaluate urban growth spatiotemporal patterns and LULC changes. This approach successfully identified the main LULC transformations and trends in the study areas while highlighting potential urbanization zones where opportunities exist for developing planned and managed urban settlements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global urbanization has reached unprecedented levels, with the world’s urban population surpassing 4.7 billion in 2023 and projected to increase by an additional 2.8 billion by 2050. This rapid urban growth is particularly pronounced in developing nations like Pakistan, where cities are expanding at an extraordinary pace due to rural–urban migration, natural population growth, and economic development1,2,3. The accelerated urbanization process has profound implications for land use patterns, natural resource consumption, and environmental sustainability, often leading to unplanned development and environmental degradation4,5,6. This urban transformation presents significant challenges for sustainable development, particularly in regions where urban expansion directly competes with agricultural productivity and natural ecosystems.

In Pakistan, urban expansion has been especially dramatic, with the urban population growing from 28% in 1990 to over 37% in 2020, and expected to reach 50% by 20502,7,8,9. Significant socio-economic changes, including industrialization, increased commercial activities, and shifts in traditional living patterns have accompanied this urbanization trend10,11,12. The rapid pace of urban growth has often outpaced planning capabilities, leading to informal settlements, inadequate infrastructure, and environmental stress13,14,15. These challenges are particularly evident in medium-sized cities, which often lack major metropolitan areas’ resources and planning capacity but face similar urbanization pressures.

The districts of Multan and Sargodha, located in Punjab province, represent significant agricultural and commercial hubs experiencing rapid urbanization that threatens traditional land use patterns and ecological balance16,17,18. Multan, known as the 'City of Saints,' has historical significance and is a major agricultural trade centre. At the same time, Sargodha, famous for its citrus production, is an important agricultural and military hub. Both cities are experiencing rapid spatial expansion, driven by population growth, economic development, and changing land use patterns11,19,20,21,22,23. The transformation of these historically agricultural regions into expanding urban centers presents unique challenges for sustainable development and environmental conservation.

The conversion of land use/land cover (LULC) in these regions stems from multiple interacting factors, including population growth, industrial development, changing economic priorities, and shifts in agricultural practices24,25,26,27. These transformations affect local ecosystems and agricultural productivity and influence regional climate patterns, water resources, and social dynamics. The loss of agricultural land to urban development is particularly concerning in Punjab province, which serves as Pakistan’s agricultural heartland and plays a crucial role in national food security. Understanding and managing these changes is essential for balancing urban development and agricultural preservation.

Recent technological advancements in remote sensing and cloud computing have revolutionized our ability to monitor and analyze urban growth patterns. The Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform, combined with machine learning algorithms and Geographic Information Systems (GIS), offers powerful tools for processing large volumes of spatial data and detecting LULC changes across temporal scales28,29. These technologies enable more accurate assessments of urban expansion trends and support evidence-based decision-making in urban planning. Integrating cloud computing platforms with traditional remote sensing techniques has enhanced our ability to process and analyze large-scale temporal data sets, making it possible to track urban growth patterns with unprecedented accuracy and detail.

The application of advanced classification algorithms, particularly Random Forest (RF) models, has significantly improved our ability to detect and categorize LULC changes30,31,32,33. When combined with cellular automata and artificial neural networks, these machine-learning approaches provide robust frameworks for analyzing historical patterns and projecting future urban growth scenarios. Incorporating these technologies into urban planning processes significantly advances our ability to understand and manage urban expansion.

Previous studies in Pakistan have examined urban growth patterns in major metropolitan areas like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. Still, comprehensive analyses of medium-sized cities like Multan and Sargodha remain limited. These cities are particularly interesting cases as they represent rapidly growing urban centers in predominantly agricultural regions, where the balance between urban development and agricultural preservation is crucial for regional food security and economic stability3,34,35,36. The unique characteristics of these cities, including their historical significance, agricultural importance, and current development trajectories, make them valuable case studies for understanding urban expansion patterns in agricultural regions.

The present study aims to evaluate urban growth patterns and LULC changes in Multan and Sargodha districts using an integrated approach combining cloud computing, GIS, and predictive modeling. This research addresses several critical gaps in our understanding of urban expansion in medium-sized Pakistani cities and provides valuable methodological insights through the application of advanced technological tools37,38,39. The objectives are to: (i) identify and classify LULC patterns using multi-temporal satellite imagery, (ii) analyze the dynamics of LULC changes from 1990 to 2020, and (iii) model potential urban growth scenarios up to 2030.

The significance of this research extends beyond the immediate study areas, offering insights into the challenges and opportunities of managing urban growth in agricultural regions throughout South Asia. By combining historical analysis with future projections, this study provides valuable information for urban planners and policymakers managing urban expansion while preserving essential agricultural lands and natural resources. The findings will contribute to our understanding of urbanization processes in developing countries and support the development of more sustainable urban growth strategies in similarly situated regions.

Materials and methods

Study area

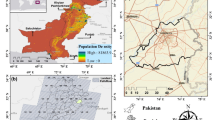

The districts of Multan and Sargodha comprise the study area and are situated in Punjab Province, Pakistan (Fig. 1). These districts represent significant urban and agricultural centers in the region, each with distinct geographical and socio-economic characteristics. Multan district lies between 30°11′52" N latitude and 71°28′11" E longitude, covering an area of approximately 3,720 km2. Located in southern Punjab, it ranges in elevation from 100 to 150 m above sea level, characterized by a predominantly flat topography with occasional gentle undulations33,40. The climate is arid to semi-arid, featuring extreme temperature variations. Summer temperatures frequently exceed 45 °C, while winters are mild with temperatures ranging from 4 to 20 °C. The district receives an average annual rainfall of 186 mm, predominantly during the monsoon season (July to September). Multan’s population reached 4.75 million in 2020, with a growth rate of 2.3% annually (PBS, 2020). The district is renowned for its agricultural production, particularly cotton, wheat, and mangoes, which form the backbone of its economy.

Sargodha district is between 32°08′00" N latitude and 72°40′00" E longitude, encompassing an area of 5,854 km2. The district is in central Punjab, with elevations ranging from 150 to 200 m above sea level. The topography is generally flat, interspersed with areas of mild relief. The climate is semi-arid, characterized by hot summers and mild winters. Average summer temperatures range from 35 to 42 °C, while winter temperatures typically vary between 6 and 21 °C (Fig. 1). Annual precipitation averages 410 mm, with the majority occurring during the monsoon season. The district’s population was recorded at 3.7 million in 2020, growing at an annual rate of 2.1% (PBS, 2020). Sargodha is particularly famous for its citrus production, earning it the title of "Pakistan’s Citrus Capital." Both districts are experiencing significant urban expansion, primarily driven by population growth, rural–urban migration, and economic development. Approximately 46% of Multan’s population and 31% of Sargodha’s population reside in urban areas. The urban centers in both districts serve as critical regional hubs for commerce, education, and administrative functions. These developments often occur in high-risk zones or on productive agricultural land, raising concerns about food security and sustainable urban development. The conversion of agricultural land to urban uses, coupled with increasing population pressure, underscores the importance of understanding and managing urban growth patterns in these historically agricultural regions.

Software and spatial data

The spatial data for this study were acquired from multiple authoritative sources. Base cartographic data, including hydrographic networks and contour lines, were obtained from the Survey of Pakistan’s geodatabase portal (https://www.surveyofpakistan.gov.pk/). Transportation network data were sourced from the National Highway Authority of Pakistan (https://nha.gov.pk/). Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data with 30 m resolution were acquired from NASA’s Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). The primary remote sensing data consisted of annual collections of Landsat 5 TM imagery (for 1990, 2000, and 2010) and Landsat 8 OLI imagery (for 2020), accessed through the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. The analysis utilized several software platforms: QGIS with the MOLUSCE plugin for spatial analysis and future predictions, ArcGIS 10.8 for advanced spatial processing, and the GEE platform for cloud-based image processing and classification. Additional processing was performed using custom Python scripts for data preparation and analysis.

Methodological processing

The methodology followed a systematic approach comprising three main phases (Fig. 2). The first phase involved satellite image preprocessing and LULC classification. The second phase focused on analyzing LULC changes across different time periods. The final phase involved modeling future urban growth scenarios for 2030.

Classification of vegetation land use and land cover

Satellite image preprocessing

Initial preprocessing began with compiling training areas for each LULC class within the study regions. Five distinct classes were identified and ground-truthed using GPS receivers: (i) agricultural land (including cropland and orchards), (ii) water bodies, (iii) built-up area, (iv) barren land, and (v) vegetation cover. Satellite imagery processing was conducted in GEE, utilizing Landsat 5 collections (ID: LANDSAT/LT05/C01/T1_SR) for historical data (1990, 2000, and 2010) and Landsat 8 (ID: LANDSAT/LC08/C01/T1_SR) for 2020. Image selection prioritized scenes with minimal cloud cover and optimal seasonal timing for land cover discrimination. Cloud masking was implemented using the C Function of Mask (CFMask) algorithm to remove cloud contamination and shadows. To enhance classification accuracy, four vegetation indices were calculated:

Vegetation indices calculation

The following spectral indices were computed to improve land cover classification, explained in Table 1.

These indices were incorporated into the classification process to improve discrimination between different land cover types, particularly between built-up areas and bare soil and between various vegetation types.

Random forest (RF) classification

The RF classification algorithm was implemented within the GEE platform to classify the multi-temporal imagery. The RF classifier was selected for its robust performance in land cover classification and ability to handle complex terrain and spectral mixing. The classification process utilized 500 trees and incorporated both spectral bands and derived indices45,46. Training data for each class were collected using a stratified random sampling approach, with a minimum of 200 training points per class47,48. The classification scheme included five LULC categories: agricultural land, water bodies, built-up areas, barren land, and vegetation cover. A minimum mappable unit of 0.5 hectares was established for consistency across all temporal classifications32.

Land use land cover change dynamics

LULC change analysis was conducted for 1990–2000, 2000–2010, and 2010–2020. Change detection utilized cross-tabulation matrices to quantify transitions between land use classes. The annual rate of change was calculated using the standardized FAO Eq. 1:

where: \(r\) = annual rate of change \(A1\) = area at initial time \(A2\) = area at final time \(t\) = number of years between measurements. Additionally, net changes, gains, and losses for each LULC class were calculated to understand the dynamics of land cover transformation49.

Modeling of future urban growth scenarios

Future urban growth prediction employed an integrated approach combining Cellular Automata (CA) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) within the MOLUSCE plugin of QGIS. The modeling process incorporated five key variables: (i) distance to existing urban areas, (ii) distance to major roads, (iii) distance to water bodies, (iv) slope, and (v) elevation.

These variables were selected based on their demonstrated influence on urban growth patterns in similar studies and their relevance to the local context of Multan and Sargodha50.

The modeling process involved several key steps to ensure accurate projections of future urban growth. First, spatial variables were prepared and standardized by converting them to a common spatial resolution. Next, transition potential maps were generated using a MLP-ANN. The ANN was trained on 10,000 sample points with a learning rate of 0.01, momentum of 0.05, 10 hidden layers, and 1000 training iterations24,51. Following the generation of transition potential maps, a CA model was implemented to allocate changes based on the transition probabilities spatially52,53.

Validation of the model was conducted using historical data to assess its accuracy. Finally, the validated model was employed to project future urban growth patterns up to the year 2030. This systematic approach ensures robust and reliable forecasts that can inform urban planning and policy development. Model validation was performed using historical data from 2010–2020 to assess prediction accuracy54. The validated model was then used to project urban growth patterns to 2030, incorporating current growth trends and spatial constraints. The entire methodological framework was designed to ensure reproducibility and reliability in analyzing historical LULC changes and projecting future urban growth scenarios for both study areas55,56.

Results

Land use and land cover classification

The multi-temporal analysis of LULC changes from 1990 to 2020 revealed significant transformations in both districts (Table 2). In Multan, vegetation cover maintained dominance but showed notable fluctuations, initially increasing from 71.02% (2596.50 km2) in 1990 to 80.15% (2,930.16 km2) in 2000, before gradually declining to 74.34% (2717.61 km2) in 2020. This pattern suggests a period of agricultural expansion followed by urban encroachment. Built-up areas demonstrated a consistent growth trajectory, nearly doubling from 6.58% (240.56 km2) in 1990 to 12.04% (440.30 km2) in 2020, with a notable peak of 14.89% (544.41 km2) in 2010. The temporary decline in built-up areas between 2010 and 2020 may be attributed to the redevelopment of older urban areas and the reclassification of some degraded urban spaces (Fig. 3).

Barren land in Multan showed the most dramatic changes, decreasing substantially from 20.75% (758.71 km2) in 1990 to 11.12% (406.62 km2) in 2020, with the most significant reduction occurring between 1990 and 2000. This trend indicates barren areas’ conversion to agricultural use or urban development. Water bodies, while occupying a relatively small portion of the total area, showed interesting variations, ranging from a minimum of 0.69% (25.25 km2) in 2000 to a maximum of 2.50% (91.29 km2) in 2020, reflecting both climatic variations and water management practices. Sargodha district exhibited distinct LULC transformation patterns. Vegetation cover showed more pronounced fluctuations than Multan, increasing from 68.38% (3938.68 km2) in 1990 to a peak of 82.85% (4776.63 km2) in 2000, before settling at 77.74% (4486.78 km2) in 2020. This pattern suggests more dynamic agricultural practices and land use changes. Built-up areas displayed a unique non-linear growth pattern, starting at 12.69% (730.91 km2) in 1990, decreasing to 6.73% (387.65 km2) in 2010, before experiencing rapid expansion to 17.83% (1029.07 km2) in 2020. This unusual pattern may reflect urban renewal programs and the redevelopment of older urban areas during the intermediate period.

The accuracy assessment of the LULC classification (Table 3) demonstrated robust reliability across all temporal classifications. Multan maintained consistently high accuracy metrics, with Overall Accuracy (OA) values ranging from 0.93 to 0.97 and Kappa Coefficient indices between 0.89 and 0.95. The highest accuracy was achieved in 1990 (OA: 0.97, Kappa: 0.95), while 2000 showed slightly lower but still excellent metrics (OA: 0.93, Kappa: 0.89). Sargodha exhibited similar high accuracy levels, with OA values between 0.88 and 0.97 and Kappa indices ranging from 0.82 to 0.95, with peak accuracy in 2000 (OA: 0.97, Kappa: 0.82).

Land use and land cover change dynamics

The transformation analysis (Table 4) revealed complex patterns of urban expansion in both districts. In Multan, the conversion of shrubland and grassland to urban areas showed a progressive increase from 80.16 ha in 1990–2000 to 531.93 ha in 2000–2020, representing a 564% increase over this period. This trend is projected to moderate, with conversions decreasing to 357.11 ha during 2020–2030. The persistence of urban areas demonstrated strong consolidation, increasing from 200.48 ha in the initial period to an expected 1,105.40 ha in 2020–2030, indicating a maturing urban landscape.

Point validation analysis (Table 5) provided additional insights into classification accuracy. In Multan, built-up areas showed consistent identification across all periods, with 16 validation points confirming the classification accuracy. The vegetation class demonstrated the highest stability in validation, with 150 points consistently identifying vegetated areas across all time periods. Water bodies and barren land showed more variable validation results, reflecting the dynamic nature of these land cover types (Fig. 4).

Sargodha’s urban transformation patterns were more intensive and complex. The conversion of shrubland and grassland to urban areas increased from 167.98 ha in 1990–2000 to 302.35 ha in 2000–2020, showing a more moderate 80% increase compared to Multan. However, the persistence of urban areas showed remarkable growth, increasing from 172.06 ha to a projected 871.98 ha, indicating more stable urban development patterns. Forest conversion to urban areas consistently declined, decreasing from 37.91 ha in 1990–2000 to an expected 5.16 ha in 2020–2030, suggesting improved forest conservation measures.

Urban growth orientation and patterns

Directional urban growth analysis (Table 6) revealed distinct spatial expansion patterns unique to each district. In Multan, the southeastern sector emerged as the primary growth direction, with urban area increasing dramatically from 26 km2 in 1990 to 283 km2 in 2030, representing a 988% increase. The eastern sector showed steady expansion from 52 km2 to 114 km2 (119% increase), while the southwestern sector accelerated growth from 29 km2 to 223 km2 (669% increase). The western and northwestern sectors also showed substantial growth but at more moderate rates.

The temporal progression of growth directions in Multan showed three distinct phases:

-

1990–2000: Dominated by eastern and western expansion

-

2000–2010: Emergence of strong southeastern growth

-

2010–2020: Multi-directional growth with southeastern dominance

Sargodha exhibited a more balanced directional growth pattern, with significant expansion in multiple directions. The northeastern sector showed the most dramatic growth, increasing from 40 km2 to 248 km2 (520% increase). The northern sector demonstrated similar strong growth from 19 km2 to 152 km2 (700% increase). The eastern sector maintained a steady growth from 32 km2 to 187 km2 (484% increase). This multi-directional growth pattern suggests more planned and distributed urban expansion than Multan’s more concentrated development (Fig. 5).

Future urban growth scenarios

The 2030 projections (Table 7) indicate divergent urban growth trajectories for the two districts. Multan’s urban area is projected to experience a slight contraction to 433.22 km2 by 2030, representing a 1.6% decrease from 2020 levels. This projection suggests a potential stabilization of urban growth and possible densification rather than spatial expansion. The decreased growth rate may be attributed to physical constraints, improved urban planning policies, or the saturation of easily developed land.

In contrast, Sargodha shows a projected dramatic increase to 1,404.97 km2 by 2030, representing a 36.5% increase from 2020. This substantial growth projection reflects the district’s more distributed development pattern and available land. The spatial distribution of this projected growth, derived from the directional analysis, suggests that Sargodha’s urban expansion will continue to follow a multi-nucleated pattern, with significant growth along transportation corridors and in peripheral areas (Fig. 6).

The validation metrics support the reliability of these projections, with both districts showing consistently high classification accuracy throughout the historical analysis period. Integrating multiple accuracy assessment methods, including point validation and statistical indices, provides robust support for the projected scenarios. These projections offer valuable insights for urban planners and policymakers in managing future urban growth and its associated challenges in both districts.

Discussion

Urban growth is a significant driver influencing LULC changes across Pakistan, and our analysis of the Multan and Sargodha districts reveals complex patterns of urban expansion and land transformation that merit detailed examination. The observed changes reflect broader regional trends while exhibiting distinct local characteristics that provide valuable urban planning and management insights.

Temporal dynamics of urban growth

Multan and Sargodha’s contrasting urban growth patterns reflect different development trajectories shaped by local socio-economic factors and geographic constraints. Multan’s urban expansion, characterized by an increase from 240.56 km2 in 1990 to 440.30 km2 in 2020, follows patterns similar to those observed in other historical cities in South Asia. This growth rate aligns with studies from comparable cities like Lahore, which experienced a 167% increase in urban areas between 1990 and 202057. However, Multan’s projected stabilization by 2030 (433.22 km2) suggests a maturing urban system, possibly influenced by geographic constraints and improved planning interventions58. Sargodha’s more dramatic urban transformation, particularly the rapid expansion from 387.65 km2 in 2010 to 1,029.07 km2 in 2020, represents a different urban growth model. This pattern more closely resembles the explosive growth seen in emerging secondary cities across developing nations59. The projected increase to 1,404.97 km2 by 2030 suggests continuing urbanization pressure, comparable to trends observed in rapidly growing secondary cities in India and Bangladesh. The contrast between these two districts highlights the diversity of urban development patterns within Pakistan’s urban system.

Land use transformation patterns

The conversion of agricultural and natural landscapes to urban areas reveals concerning trends in both districts. In Multan, the significant reduction in barren land from 20.75 to 11.12% between 1990 and 2020 indicates intensive land transformation, often preceding urban development. This pattern mirrors trends observed in other agricultural regions experiencing rapid urbanization, such as India’s Punjab region, where similar losses of agricultural buffer zones have been documented.

Sargodha’s more complex transformation pattern, including the fluctuation in built-up areas and the dramatic reduction in barren land from 17.46 to 1.50%, suggests a more dynamic land use system60. The preservation of vegetation cover at 77.74% by 2020 indicates a more successful balance between urban growth and agricultural conservation than other rapidly urbanizing districts in Pakistan. This success may offer valuable lessons for regional planning policies.

Directional growth and spatial planning implications

The directional analysis of urban growth reveals important patterns with significant planning implications. Multan’s predominantly southeastern expansion (from 26 to 283 km2) follows transportation corridors and topographic constraints, a pattern common in historically established cities. However, this concentrated growth direction may lead to urban management challenges, including traffic congestion and service delivery inefficiencies, similar to those observed in other rapidly growing South Asian cities59,61. Sargodha’s more balanced directional growth, with significant expansion in multiple directions (northeast: 40 km2 to 248 km2, north: 19 km2 to 152 km2), represents a potentially more sustainable model of urban development. This pattern allows for more efficient infrastructure distribution and may reduce pressure on any single sector of the city60. The multi-directional growth pattern also provides more significant opportunities for planned development and the integration of green spaces, similar to successful urban planning models implemented in other developing regions.

Environmental and agricultural implications

The transformation of land use patterns in both districts raises significant environmental and agricultural concerns. In Multan, reducing vegetation cover and converting agricultural land to urban uses threatens the region’s agricultural productivity. This trend is particularly concerning given Punjab’s role as Pakistan’s agricultural heartland and the increasing challenges of food security in the face of climate change62. Sargodha’s relatively better preservation of vegetation cover offers a potential model for balancing urban growth with agricultural preservation. However, the projected urban expansion to 1,404.97 km2 by 2030 may pose new challenges to this balance. The experience of both districts underscores the need for integrated urban–rural planning approaches that protect agricultural resources while accommodating necessary urban growth.

Methodological insights and planning applications

The high accuracy levels achieved in our classification (OA > 92%) validate the methodological approach and provide reliable foundations for planning applications. Integrating multiple data sources and advanced classification techniques offers a robust framework for monitoring urban growth in similar contexts63,64. The successful application of the Random Forest classifier, combined with multiple vegetation indices, demonstrates the potential for replicating this approach in other rapidly urbanizing regions.

Planning and policy implications

The findings from this study offer critical insights for urban planning and policy, emphasizing the need for tailored approaches to managing growth. The contrasting urban expansion patterns in Multan and Sargodha highlight the necessity of distinct strategies for consolidation and redevelopment policies for Multan and frameworks to manage rapid expansion for Sargodha65. The significant conversion of agricultural lands into urban areas calls for stronger protection measures to preserve prime agricultural zones, especially in peri-urban regions. Additionally, the identified directional growth patterns should guide infrastructure planning, ensuring that new developments are well-supported by transportation and public utilities in rapidly growing sectors66. Lastly, reducing natural land cover underscores the urgent need for integrated green space planning and environmental conservation measures to promote sustainable urban development.

Future challenges and opportunities

Both districts face significant challenges in managing urban growth while ensuring environmental and agricultural sustainability. The projected growth patterns highlight several key areas requiring immediate attention. Transportation infrastructure will be a crucial focus, particularly in Multan’s southeastern sector, where concentrated growth may lead to congestion and accessibility issues if careful transportation planning is not implemented. The increased urban density could hinder mobility and economic activities without proper road networks and public transit systems. Moreover, environmental sustainability remains a pressing concern as continued loss of vegetation cover and natural areas poses risks to biodiversity, air quality, and overall urban livability. Innovative approaches to urban greening, such as green belts, rooftop gardens, and the preservation of natural ecosystems, will be essential to mitigate these impacts67.

In addition, maintaining agricultural productivity amid expanding urban areas will be increasingly critical, especially in Sargodha, where rapid growth is projected. With agriculture being a vital component of the local economy, urban planners must balance accommodating new development and preserving fertile agricultural land. Strategies such as controlled urban sprawl and promoting vertical growth could help preserve valuable farmland. Lastly, social integration will require targeted interventions to address the challenges of different growth patterns in both districts. Ensuring equitable access to social services, education, healthcare, and employment opportunities across expanding urban areas will be key to fostering cohesive and inclusive communities. Addressing these multifaceted challenges will be essential for promoting sustainable urban development in Multan and Sargodha.

Research limitations and future directions

While this study provides valuable insights into urban growth patterns and their environmental implications, several limitations and areas for future research emerge that could enhance the robustness of future analyses. One key limitation is the temporal resolution of the data used. More frequent temporal sampling could offer a finer-grained understanding of land use changes, allowing researchers to capture rapid urban transitions and short-term fluctuations in land cover more accurately68. Additionally, the study lacks an in-depth integration of socioeconomic factors, which significantly drive urban growth. Incorporating detailed socioeconomic data, such as population density, economic activities, and infrastructure development, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying drivers of land use changes69. This approach would allow for a more nuanced analysis of the relationship between human activities and urban expansion, contributing to more targeted policy recommendations.

Another area for improvement is the incorporation of climate change projections in future research. Urban growth impacts local climates and is influenced by broader climatic changes. Including climate projections could help researchers better understand the long-term environmental implications of urbanization and identify strategies to enhance urban resilience to climate-related risks, such as heatwaves, flooding, and water scarcity. Furthermore, future studies could focus on evaluating the effectiveness of existing planning policies in managing urban expansion. Assessing current policies’ performance in controlling urban sprawl and preserving agricultural lands and natural resources would offer valuable lessons for future management strategies. This could guide policymakers in revising or introducing new regulations to promote sustainable urban development.

Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of urban growth patterns, and LULC changes in the Multan and Sargodha districts of Pakistan from 1990 to 2030, utilizing an integrated approach combining cloud computing, GIS, and predictive modelling. Through the analysis of five distinct LULC classes, the research revealed significant transformations in both districts’ urban landscapes. The classification achieved consistently high accuracy levels exceeding 92% with robust Kappa indices, validating the reliability of the analytical approach and providing a solid foundation for urban growth projections. The multi-temporal analysis demonstrated contrasting patterns of urban expansion between the two districts. Multan’s built-up area increased from 240.56 km2 (6.58%) in 1990 to 440.30 km2 (12.04%) in 2020, showing a concentrated growth pattern primarily in the southeastern direction. In contrast, Sargodha experienced more dramatic growth from 730.91 km2 (12.69%) to 1,029.07 km2 (17.83%) during the same period, exhibiting a more balanced multi-directional expansion. Despite these transformations, vegetation cover remained the dominant land use type in both districts, though its extent fluctuated due to urban expansion and agricultural intensification.

Future projections for 2030 reveal divergent growth trajectories for the two districts. Multan’s urban area is expected to stabilize around 433.22 km2, suggesting a maturation of its urban development pattern. In contrast, Sargodha is projected to experience continued rapid expansion, reaching 1,404.97 km2 by 2030. These distinct growth patterns highlight the need for tailored urban management strategies for each district’s unique development challenges and opportunities. The conversion of agricultural and natural landscapes to urban areas emerged as a significant concern, particularly in peri-urban zones, emphasizing the importance of balanced development approaches that protect essential agricultural resources.

These findings provide valuable insights for urban planners and policymakers managing urban expansion while preserving essential agricultural lands and natural resources in Pakistan’s growing cities. The study demonstrates the importance of integrated planning approaches that balance development needs with environmental conservation, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions. The methodology and results can serve as a framework for similar analyses in other developing regions facing comparable challenges of managing urban growth while maintaining environmental and agricultural sustainability.

In the future research should focus on incorporating more detailed socioeconomic factors, climate change impacts, and policy effectiveness evaluations to enhance further our understanding of urban growth dynamics in these rapidly evolving regions. Integrating these additional factors would provide even more comprehensive insights for sustainable urban development planning, helping to ensure the long-term viability of both urban and agricultural systems in Pakistan’s evolving landscape.

Data availability

Data available upon request to the corresponding author (sajidjalwan@gmail.com).

References

Asif, M. et al. Modelling of land use and land cover changes and prediction using CA-Markov and Random Forest. Geocarto Int. 38, (2023).

Asif, M., Kazmi, J. H. & Tariq, A. Traditional ecological knowledge based indicators for monitoring rangeland conditions in Thal and Cholistan Desert, Pakistan. Environ. Challenges 13, 100754 (2023).

Bokhari, R. et al. Land subsidence analysis using synthetic aperture radar data. Heliyon vol. 9 at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14690 (2023).

Zhao, Z. et al. Comparison of three machine learning algorithms using google earth engine for land use land cover classification. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 92, 129–137 (2024).

Tariq, A. & Mumtaz, F. Modeling spatio-temporal assessment of land use land cover of Lahore and its impact on land surface temperature using multi-spectral remote sensing data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 23908–23924 (2022).

Barboza, E. et al. Analyzing urban expansion and land use dynamics in Bagua grande and chachapoyas using cloud computing and predictive modeling. Earth Syst. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-024-00470-5 (2024).

Ullah, N. et al. Geospatial analysis and AHP for flood risk mapping in Quetta, Pakistan: A tool for disaster management and mitigation. Appl. Water Sci. 14, 236 (2024).

Tariq, A. & Qin, S. Spatio-temporal variation in surface water in Punjab, Pakistan from 1985 to 2020 using machine-learning methods with time-series remote sensing data and driving factors. Agric. Water Manag. 280, 108228 (2023).

Hao, Z. et al. Multitemporal analysis of urbanization-driven slope and ecological impact using machine-learning and remote sensing techniques. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 18, 1876–1895 (2025).

Aslam, R. W., Shu, H. & Yaseen, A. Monitoring the population change and urban growth of four major Pakistan cities through spatial analysis of open source data. Ann. GIS 1–13 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1080/19475683.2023.2166989.

Aslam, R. W. et al. Monitoring landuse change in Uchhali and Khabeki wetland lakes, Pakistan using remote sensing data. Gondwana Res. 129, 252–267 (2024).

Gulshad, K., Szydłowski, M., Yaseen, A. & Aslam, R. W. A comparative analysis of methods and tools for low impact development (LID) site selection. J. Environ. Manage. 354, 120212 (2024).

Wang, N. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of rangeland transformation using machine learning algorithms and remote sensing data. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 94, 106–118 (2024).

Aslam, R. W., Shu, H., Yaseen, A., Sajjad, A. & Abidin, S. Z. U. Identification of time-varying wetlands neglected in Pakistan through remote sensing techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 74031–74044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-27554-5 (2023).

Aslam, R. W. et al. Wetland identification through remote sensing: Insights into wetness, greenness, turbidity, temperature, and changing landscapes. Big Data Res. 100416 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bdr.2023.100416.

Naz, I., Ahmad, I., Aslam, R. W., Quddoos, A. & Yaseen, A. Integrated assessment and geostatistical evaluation of groundwater quality through water quality indices. Water 16, 63 (2023).

Lingye, T. et al. Assessment of urban environmental quality by socioeconomic and environmental variables using open-source datasets. Trans. GIS https://doi.org/10.1111/tgis.13250 (2024).

Aslam, R. W., Naz, I., Shu, H., Yan, J. & Tariq, A. Multi-temporal image analysis of wetland dynamics using machine learning algorithms. J. Environ. Manage. 370, 122490 (2024).

Aslam, R. W. et al. Machine learning-based wetland vulnerability assessment in the sindh province ramsar site using remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 16, 928 (2024).

Chaoyong, W. et al. SAR image integration for multi-temporal analysis of Lake Manchar Wetland dynamics using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 14, 26669 (2024).

Quddoos, A., Muhmood, K., Naz, I., Aslam, R. W. & Usman, S. Y. Geospatial insights into groundwater contamination from urban and industrial effluents in Faisalabad. Discov. Water 4, 50 (2024).

Feng, L. et al. Exploring rangeland dynamics in Punjab, Pakistan: Integrating LULC, LST, and remote sensing for ecosystem analysis (2000–2020). Rangel. Ecol. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2024.09.008 (2024).

Naz, I. et al. Integrated geospatial and geostatistical multi-criteria evaluation of urban groundwater quality using water quality indices. Water 16, 2549 (2024).

Tariq, A. & Shu, H. CA-Markov chain analysis of seasonal land surface temperature and land use landcover change using optical multi-temporal satellite data of Faisalabad, Pakistan. Remote Sens. 12, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12203402 (2020).

Singh, S. & Rai, P. K. Application of earth observation data for estimation of changes in land trajectories in Varanasi District, India. J. Landsc. Ecol. Republic) 11, 5–18 (2018).

Mohiuddin, G. & Mund, J.-P. Spatiotemporal analysis of land surface temperature in response to land use and land cover changes: A remote sensing approach. Remote Sens. 16, 1286 (2024).

Tariq, A., Shu, H., Siddiqui, S., Imran, M. & Farhan, M. Monitoring land use and land cover changes using geospatial techniques, a case study of Fateh Jang, Attock, Pakistan. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 14, 41–52. https://doi.org/10.24057/2071-9388-2020-117 (2021).

Tan, J., Yu, D., Li, Q., Tan, X. & Zhou, W. Spatial relationship between land-use/land-cover change and land surface temperature in the Dongting Lake area, China. Sci. Rep. 10, 9245 (2020).

Maskooni, E. K., Naghibi, S. A., Hashemi, H. & Berndtsson, R. Application of advanced machine learning algorithms to assess groundwater potential using remote sensing-derived data. Remote Sens. 12, 2742 (2020).

Luo, M. et al. Improving forest above-ground biomass estimation by integrating individual machine learning models. Forests 15, 975 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Annual wetland mapping in metropolis by temporal sample migration and random forest classification with time series landsat data and google earth engine. Remote Sens. 14, 3191 (2022).

Cutler, R. et al. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 88(11), 2783–2792 (2007).

Arshad, A., Mirchi, A., Vilcaez, J., Umar Akbar, M. & Madani, K. Reconstructing high-resolution groundwater level data using a hybrid random forest model to quantify distributed groundwater changes in the Indus Basin. J. Hydrol. 628 (2024).

Lu, L. et al. Spatiotemporal variation of surface urban heat islands in relation to land cover composition and configuration: A multi-scale case study of Xi’an, China. Remote Sens. 12, 2713 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Analysis on decoupling between urbanization level and urbanization quality in China. Sustainability 12, 6835 (2020).

Faichia, C. et al. Using RS data-based CA–Markov model for dynamic simulation of historical and future LUCC in vientiane, Laos. Sustainability 12, 8410 (2020).

Rwanga, S. S. & Ndambuki, J. M. Accuracy assessment of land use/land cover classification using remote sensing and GIS. Int. J. Geosci. 08, 611–622 (2017).

Mahboob, M. A., Atif, I. & Iqbal, J. Remote sensing and GIS applications for assessment of urban sprawl in Karachi, Pakistan. Sci. Technol. Dev. 34, 179–188 (2017).

Fang, Y. et al. Assessment of the hydrodynamics role for groundwater quality using an integration of GIS, water quality index and multivariate statistical techniques. J. Environ. Manage. 273, 111185 (2020).

Ullah, H. et al. Geo-spatial analysis and modelling of water borne diseases in District Multan. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 12, 1–15 (2021).

Defries, R. S. & Townshend, J. R. Ndvi-derived land cover classifications at a global scale. Int. J. Remote Sens. 15, 3567–3586 (1994).

Huete, A. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 25, 295–309 (1988).

Rocha, A. V. & Shaver, G. R. Advantages of a two band EVI calculated from solar and photosynthetically active radiation fluxes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 149, 1560–1563 (2009).

Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 27, 3025–3033 (2006).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Prasad, A. M., Iverson, L. R. & Liaw, A. Newer classification and regression tree techniques: Bagging and random forests for ecological prediction. Ecosystems 9, 181–199 (2006).

Ullah, S., Qiao, X. & Tariq, A. Impact assessment of planned and unplanned urbanization on land surface temperature in Afghanistan using machine learning algorithms: A path toward sustainability. Sci. Rep. 15, 3092 (2025).

Ullah, S., Qiao, X. & Abbas, M. Addressing the impact of land use land cover changes on land surface temperature using machine learning algorithms. Sci. Rep. 14, 18746 (2024).

Ullah, S., Abbas, M. & Qiao, X. Impact assessment of land-use alteration on land surface temperature in Kabul using machine learning algorithm. J. Spat. Sci. 1–23 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1080/14498596.2024.2364283.

Sayemuzzaman, M. & Jha, M. K. Modeling of future land cover land use change in North Carolina using Markov chain and cellular automata model. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 7, 295–306 (2014).

Farhan, M. et al. Predicting land use land cover dynamics and land surface temperature changes using CA-Markov-Chain models in Islamabad, Pakistan (1992–2042). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 1–18 (2024).

Mohamed, A. & Worku, H. Simulating urban land use and cover dynamics using cellular automata and Markov chain approach in Addis Ababa and the surrounding. Urban Clim. 31, 100545 (2020).

Abdul Rahaman, S., Aruchamy, S., Balasubramani, K. & Jegankumar, R. Land use/land cover changes in semi-arid mountain landscape in Southern India: A geoinformatics based Markov chain approach. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. - ISPRS Arch. 42, 231–237 (2017).

Ullah, S., Khan, M. & Qiao, X. Examining the impact of land use and land cover changes on land surface temperature in Herat city using machine learning algorithms. GeoJournal 89, 225 (2024).

Sang, L., Zhang, C., Yang, J., Zhu, D. & Yun, W. Simulation of land use spatial pattern of towns and villages based on CA–Markov model. Math. Comput. Model. 54, 938–943 (2011).

Farhan, M. et al. Predicting land use land cover dynamics and land surface Temperature changes using CA-Markov-chain models in Islamabad, Pakistan (1992–2042). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 17, 16255–16271 (2024).

Shirazi, S. A. & Kazmi, S. J. H. Analysis of population growth and urban development in Lahore-Pakistan using geospatial techniques: Suggesting some future options. South Asian Stud. 29, 269–280 (2014).

Waseem, M., Mutahir Ullah Ghazi, S., Ahmed, N., Ayaan, M. & Kebede Leta, M. Rainwater harvesting as sustainable solution to cope with drinking water scarcity and urban flooding: A case study of public institutions in Lahore, Pakistan. CivilEng 4, 638–656 (2023).

Khan, M. K., Naeem, K., Huo, C. & Hussain, Z. The nexus between vegetation, urban air quality, and public health: An empirical study of Lahore. Front. Public Heal. 10, 1–21 (2022).

Khanum, F., Chaudhry, M. N. & Kumar, P. Characterization of five-year observation data of fine particulate matter in the metropolitan area of Lahore. Air Qual. Atmos. Heal. 10, 725–736 (2017).

Riaz, O., Ghaffar, A. & Butt, I. Modelling Land use Patterns of Lahore (Pakistan) using remote sensing and GIS. Glob. J. Sci. Front. Res. H Environ. Earth Sci. 14, 24–30 (2014).

Iram, A., Rasool, L., Shahzad, F. & Saeed, Y. Impact of urban sprawl on public health: An analysis of Lahore—Pakistan. World Appl. Sci. J. 20, 80–86 (2012).

Zia, S. M., Shirazi, S. A. & Alam, R. Temporal analysis of temperature trends in the metropolitan area of Lahore, Pakistan. Pak. J. Sci. 66, 83–88 (2014).

Jabeen, F., Ali, Z. & Maharjan, A. Assessing health impacts of winter smog in lahore for exposed occupational groups. Atmosphere (Basel). 12, 1–14 (2021).

Mahmood, K. et al. Groundwater Levels Susceptibility To Degradation in Lahore Metropolitan. Depression 25, 123–126 (2000).

Muhammad, A. M., Zhonghua, T., Dawood, A. S. & Earl, B. Evaluation of local groundwater vulnerability based on DRASTIC index method in Lahore, Pakistan. Geofísica Int. 54, 67–81 (2015).

Ali, M. et al. A study of aerosol properties over Lahore (Pakistan) by using AERONET data. Asia-Pacific J. Atmos. Sci. 50, 153–162 (2014).

Jiang, Z. & Xu, C. Policy incentives, government subsidies, and technological innovation in new energy vehicle enterprises: Evidence from China. Energy Policy 177, 113527 (2023).

Arima, E. Y., Simmons, C. S., Walker, R. T. & Cochrane, M. A. Fire in the Brazilian Amazon: A spatially explicit model for policy impact analysis. J. Reg. Sci. 47, 541–567 (2007).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their invaluable comments for improving the quality of the manuscript. We are grateful to USGS for providing free-of-cost satellite imagery. The authors acknowledge the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R951), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AZ: Conceptualization; methodology; software; validation, formal analysis; investigation; AT, AQ, IN and RWA, SU, MAW.: resources; AT, and RWA.: data curation; ATEB, IN and AQ; writing original draft preparation.; AZ, MAW, SU AT and AQ.: writing review and editing; visualization, AT; supervision, MAW and SU; project administration, SU.; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Software

Maps and spatial analyses in this study were generated using ArcGIS version 10.8 (Esri Inc., Redlands, CA, USA; https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/about-arcgis/overview).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, A., Tariq, A., Quddoos, A. et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of urban expansion and land use dynamics using google earth engine and predictive models. Sci Rep 15, 6993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92034-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92034-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Satellite-Based Assessment of Urban Air Pollution Dynamics in Arak City with Implications for Public Health Risk

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2026)

-

Modeling and predicting land use and land cover changes using remote sensing in tropical coastal ecosystems of southern Peru

Environmental Sciences Europe (2025)

-

Explore sustainable practices in landscape construction and enhance the environmental and cultural sustainability of characteristic towns

GeoJournal (2025)

-

Examining the relationship among land surface temperature (LST), land use/land cover (LULC) and spectral indices in Kunar Province, Afghanistan

GeoJournal (2025)

-

The inheritance and regional differences of traditional national sports from the perspective of cultural and historical geography

GeoJournal (2025)