Abstract

In recent years, concerns about the environment and the depletion of fossil fuels have encouraged the incorporation of electric vehicle technology in the automotive market. As the increasing usage and growth of electric vehicles (EVs) along with the advancement of power electronic converters significantly impact the power quality of the electrical grid. This paper addresses a new ongoing power quality issue known as supraharmonics, which occurs in the frequency range of 2 to 150 kHz due to electric vehicle chargers. Among various levels of EV chargers, DC fast chargers have become more popular in recent years for quick charging of batteries. The charging time of the EV mainly depends on the optimized selection of the DC-DC converter implemented in the charging circuit. The effective use of a DC-DC converter should increase battery performance and lifespan. Consequently, this work investigates the supraharmonic emissions produced by a DC fast charging station with four number of chargers connected to an electrical distribution system. Several DC/DC converter topologies in EV fast chargers were designed and developed using MATLAB/Simulink software. The simulation has been carried out to analyze the supraharmonic emission from the designed converter topologies in different operating conditions. The results of the simulations have been analyzed for comparative analysis of supraharmonic emission from different converter topologies. Finally, from the analysis, a suitable converter topology with reduced supraharmonic emission has been suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transportation sector has a significant influence on the economy and environment of a country. The primary mode of transportation in the world is an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle. Due to the fact that internal combustion engines (ICEs) use fossil fuel and produce carbon dioxide (CO2), their increasing use is having a negative impact on both the environment and people. Electric vehicles have been developed as a result of the pollutants from internal combustion engines, which have caused climate change1. An important consideration is the power source for charging. Electric vehicles (EVs) can be charged by both the electrical grid and renewable energy sources. Hence, power electronic-based converters play an important role in providing charging facilities for electric vehicles2. Therefore, the rise of electric vehicles and improvements in power converter topology have created new challenges in the modern power system that have an impact on power quality3. In the modern power system, a recently identified power quality issue is known as supraharmonics (SH). Supraharmonics refers to distortions in voltage or current waveforms that occur within the frequency range of 2 to 150 kHz. Due to its adverse effects, the analysis of supraharmonic emissions has become a significant research area in recent years4,5. This emission leads to diverse effects on power distribution systems such as malfunctioning of sensitive loads, light flickering, audible noise generation, control circuit malfunctions, and undesired tripping of current devices6.

The SH emission generated by electrical loads may flow through the nearby devices and affects the functioning of the corresponding equipment7. PV inverters, Electric Vehicle (EV) chargers, street lights, converters in wind energy conversion systems, and power line communication (PLC) are the sources of SH emission8,9. In different countries, the frequency range employed for power line communication is in the SH range and it acts as an intentional source of SH emission. Power electronic converters among other sources are considered to be unintentional sources of supraharmonic emission10. Generally, supraharmonic emission has been classified into two types: primary and secondary emissions11. Load-flow models developed for traditional harmonics are not sufficient to develop a mathematical model of supraharmonic emissions12. Figure 1 illustrates the simple and ideal model proposed by Tim Slangen et al. to describe the primary and secondary supraharmonic emissions. In Fig. 1 the ISH1 and ISH2 depict the supraharmonic current of devices 1 and 2 respectively. Z1 and Z2 are the internal device impedances of devices 1 and 2, respectively, and Zg is the grid impedance. I1 is the primary emission of device 1 and I12 is the secondary emission of device 1.

THD is the term proposed by IEEE 519 to measure traditional harmonics. The term THD13,14,15 is defined as to quantification of the waveform distortion by taking the square root of the sum of the squares of individual harmonic components and dividing it by the RMS voltage of the fundamental frequency. Despite there being no specific standards for supraharmonic emissions, international standardizing organizations like the IEC and IEEE are giving serious attention to addressing this issue16. A number of informative standards were suggested by different working groups17. Informative standards, such as the European Standard EN-50065-1, provide guidelines for supraharmonic emissions from PLCs. Meanwhile, International Standards CISPR 15 and CISPR 14 − 1 define emission limitations for induction cooktops and lighting systems in the frequency range of 9–150 kHz, respectively. However, normative standards for intentional and unintentional sources of SH have yet to be established18,19. Several studies investigated the occurrence of supraharmonic emission from numerous sources using different measurement standards12,20,21,22,23.

Recently, Electric vehicles have become a growing sector due to minimizing the usage of fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions. In compliance with the Paris Climate Agreement, many nations have limited the use of gasoline- and diesel-powered cars24. For instance, Norway and the Netherlands have committed to prohibiting the sale of gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles by 2025 and 2030, respectively25. Several governments, including India, have developed several programmes, regulations, and subsidies to encourage the use of EVs worldwide. China, Norway, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Iceland, and Sweden are some of the countries that have large e-mobility industries26. The government of India expects that by 2050, e-mobility would have completely replaced traditional modes of transportation27. Also, the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) hopes to have an EV charging station installed every 40 to 60 km along 35,000 to 40,000 km of national highways28. As a result of this scenario, the power quality of the electrical network is impacted by the non-linear properties of EV chargers. Hence the power system is expected to be affected by more supraharmonic emissions in the near future.

EVs can be charged through different methods such as wireless charging method, wired charging method, and battery swapping method. The most common EV charging technique is the wired or conductive charging method. Electric Vehicle Charging Stations can be either AC or DC charging stations. AC Level-1, AC Level-2, and DC fast or Level-3 charging are conductive types of EV charging levels classified by The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) and the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE). Normal or slow charging is referred to as Level 1, semi-quick charging is referred to as Level 2, fast charging is referred to as Level 3, and ultra-fast charging is referred to as Level 4. Level 3 off-board chargers are frequently used in commercial charging stations as public charging stations29,30,31.

Table 1 depicts the power output and charging duration of different chargers. Level 1 and level 2 chargers can take several hours to fully charge a battery, while level 3 DC fast charging stations have the capacity to charge large batteries in under 30 min, as indicated in Table 1. Achieving long-range travel by vehicle requires frequent recharging as well as quick charging32. In this account, the fast-charging station is desired to successfully incorporate electric vehicles and transform full electrical transportation. The extensive usage of EV fast charging stations increases the power demand on the electrical network as well as creates power quality issues in the grid33,34,35. Hence this paper evaluates the supraharmonic emission from Level 3 EV fast chargers.

A Level 3 DC fast charging station comprises a front-end rectifier and a DC-DC converter circuit. Both the AC-DC converter and DC-DC converter of the EV charger emit supraharmonics. In this analysis, the DC-DC converter has been considered as test equipment. A number of DC-DC converter topologies are available for DC Fast Chargers (DFC)36. The DC-DC converter is classified into isolated and non-isolated converters. Non-isolated DC-DC converters are employed for EV fast chargers with low to moderate power levels. In the absence of a transformer or components for galvanic isolation, they are simpler in design and occupy less space as compared to isolated converters. Fewer components in non-isolated types of converters lead to cost reduction and easier implementation. Isolated DC-DC converters are used in high-power EV chargers. As it requires additional components for isolation, this type of converter is complicated in structure and expensive37.

A lot of research is ongoing to analyze supraharmonic emissions. In the field of electric vehicles, the following works were done by the researchers to identify SH emissions. Dilini Darmawardana et al.38investigated the supraharmonic emissions due to DC fast chargers and Level 1 onboard chargers. The author stated that the characteristics of both the charger and the vehicle influence the high-frequency emissions. Tim Slangen et al.12 examine the behaviour of supraharmonic emissions from various EVs connected to a medium voltage grid. According to the authors, DC fast chargers are the primary source of SH. The authors also inferred that the distribution transformers act as a medium for supraharmonic emissions from the low voltage side to the medium voltage side. Fuqiang Chen et al.39 measured supraharmonic emissions from five EV chargers that had different power ratings located across two different countries. According to the authors switching frequency of the EV chargers has a significant impact on the supraharmonic frequency. Bernhard Grasel et al.40 analyzed the SH emission from the bidirectional EV charging station. The author describes the primary emission of SH emission coming from the charging station and discovers that supraharmonic emission interferes with the operation of the devices. Tim Slangen et al.41 analyzed two 175 kW fast charging stations and observed supraharmonic emission from the chargers. The author proposed the distribution of supraharmonic emission in the grid about the magnitude of the DC voltage of the charger. The author arrived at the conclusion that the DC output of the charger mainly influences the supraharmonic emission. Tim Streubel et al.42 evaluated three different level 2 chargers in three distinct locations. According to scientists, SH emission interrupts EV batteries from charging. Tim Slangen et al.43 studied the DC fast chargers, and it was found that when the number of active chargers rises, the total supraharmonic current also rises. This increase is unpredictable because the emissions are time-varying.

In this work, we mainly analyze the supraharmonic emission from electric vehicle chargers. Most of the supraharmonic emission studies in the literature concentrated on the overall topology of the EV charger. At the same time, the distortion effects caused by the DC-DC converters used in Level 3 chargers are not fully discussed. Therefore, this work mainly focuses on supraharmonic emissions by both non-isolated and isolated type DC-DC converters-based EV chargers. In this paper, the SEPIC converter, Cuk converter, Flyback converter, and Full bridge converter are the non-isolated and isolated DC-DC converters chosen respectively for the analyses. Both types of converters are designed for the same power ratings to charge the EV battery of 150Ah. All the designed converters for the charging infrastructure have been simulated using MATLAB Simulink software. This study identifies high-frequency harmonics within the 2 kHz to 5 kHz range, which is in the range of SH emission. The results of the simulation have been discussed for the level of supraharmonic emissions emitted by different DC-DC converter topologies operated in coordination mode and single mode. This paper is structured as follows Sect. 2 explains the methodology and also discusses the design parameters for developing DC-DC converters of the EV fast chargers. Section 3 presents the simulation output and is followed by a comprehensive discussion of the results obtained from the simulation. Section 4 presents the experimental results of the prototype and Sect. 5 concludes with the outcomes of the proposed system.

Methodology

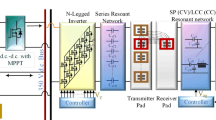

Figure 2 shows the block diagram of the proposed work, it includes an EV fast charging station and a 3-phase linear load. The charging station contains four fast charging outlets that are connected to the distribution system. The primary objective of this research is to investigate the frequency range of supraharmonic emissions from EV charging stations as well as the Total Harmonic current Distortion (THD) from the whole setup. A three-phase supply taken from the grid with a line voltage of 440 V is connected to the charging station. A common alternating current (AC) bus is employed to efficiently distribute power among the EV chargers and the linear load. A two-stage conversion charging module has been designed and implemented for the DFC. In the first stage, an AC-DC converter is used to convert AC to DC. The second step of the EV charger is the DC-DC converter, which controls and adjusts the voltage to meet the requirements of the EV battery charger.

Using this setup, the measurement of supraharmonic emission has been performed in the frequency domain. Anne Grevener et al.44 proposed the term Total Supraharmonic Current (TSHC) index for calculating the supraharmonic emission. The total supraharmonic current (TSHC)44,45is calculated using Eq. (1) by considering the minimum frequency (fmin) and maximum frequency (fmax) as 2 kHz and 150 kHz respectively and Is is the RMS current value.

In this paper, the spectrum analyzer tool in MATLAB software has been used to analyze the supraharmonic emission.

Design of Front-End AC-DC converter

The front-end AC-DC converter has been chosen as an active three-phase bridge rectifier to supply the DC voltage to the DC-DC converter. A 25MVA distribution transformer provides a 440-volt, 50 Hz, three-phase alternating current (AC) supply to the converter. As mentioned in Table 1, the power rating of a Level 3 fast charger is generally, in the range of 50 kW to 350 kW. Accordingly, each fast charger as shown in Fig. 1 has been designed with a power rating of 80 kW to charge a 150Ah battery. Therefore, the front-end converter with a 90 kW output power has been developed for each of the EV chargers. The topology of the designed four different types of EV chargers is supplied by the same type of front-end converter. The simulation circuit of the front-end converter has been depicted in Fig. 3.

The output voltage of a three-phase bridge rectifier has been calculated by using Eq. 2, where V0 is the output DC voltage, VS is the supply voltage, and α is the firing angle. The firing angle(α) has been modified to obtain the desired output voltage of the front-end rectifier. The switches of the front-end converter have been triggered at a firing angle (α) 53° to obtain the desired direct current output voltage of 620 V.

Design of non-isolated and isolated DC-DC converters

This section describes the design of DC-DC converter topologies utilized in the proposed work. Basicly, the DC-DC converters have been classifed into isolated and non isolated type of converters. The type of DC-DC converters employed for the EV charger application can be determined by the specific needs of the EV charger, safety considerations, size limits, cost considerations, and converter characteristics. Both non isolated and isolated type of DC-DC converter have been chosen in this work to analyse the SH emission. All the converters used in this work have been designed for an output power of 80 kW to charge a 550 V, 150 Ah lithium-ion battery. These converters have been designed to provide the 550 V DC voltage required for battery charging from the 620 V input DC voltage.

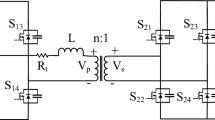

Figure 4(a) illustrates the Cuk converter, named after its inventor, which can either step up or step down the input voltage. Its operation is similar to the conventional buck-boost converter and includes an active switch, diode, inductors, and capacitors. Figure 4(b) shows the SEPIC converter, a non-isolated DC-DC converter topology that can also step up or step down the input voltage while maintaining a positive output polarity. It consists of an active switch and five passive components. Figure 4(c) and 4(d) depict the isolated DC-DC converters, such as the full-bridge and flyback converters. The full-bridge DC-DC converter topology includes a high-frequency inverter, a center-tapped transformer, a diode rectifier, and a filter circuit. In this work, a unidirectional full-bridge converter is used to design the charger topology. This topology reduces switching losses and efficiently handles high power levels. The flyback converter consists of a switch, transformer, diode, and capacitor. It is known for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to both step up and step down voltage. It is commonly used in low- to medium-power applications. Both the full-bridge and flyback converters provide electrical isolation between the input and output via a transformer.

Passive components are essential in ensuring efficient power conversion and reliable operation of the converter. The passive components employed in all the converters are the inductor and the capacitor, which smooth the input voltage and control the output to the appropriate value.

The size of the passive components used in the circuit has been calculated based on the switching frequency of each converter topology. Table 2 shows the design formulas to choose the value of L and C parameters of the DC-DC converters36,37. A Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) pulse generator is used to control the switching of the converters, it produces appropriate switching pulses to operate the converter. The Proportional Integral (PI) controller has been implemented in the work and it continuously examines the output voltage of the converter and modifies the control signal to keep the desired voltage level.

Simulation results and discussion

Figure 5 shows the general simulation circuit of a DC Fast charging station proposed in this work. The whole EV charging set up along with linear load modeled and simulated in MATLAB/Simulink/Simscape software. The charging station and linear load have power ratings of 320 kW and 10 kW, respectively. Table 3 shows the key specifications of the proposed simulation setup. The frequency spectrum of the current signal has been examined to analyze the supraharmonic emissions at the point of common coupling (PCC) using single-sided spectrum analyzer.

The entire simulation set-up has been used to investigate the features and behaviour of the supraharmonic emissions under the following four operating conditions.

Condition 1: A single EV charger module connected to the grid and operated at different switching frequency.

Condition 2: Multiple EV charger modules connected sequentially to the grid with the same topology.

Condition 3: Multiple EV charger modules with different topologies connected simultaneously to the grid, operating at the same switching frequency.

Condition 4: Multiple EV charger modules with different topologies connected simultaneously to the grid, each operating at different switching frequencies.

The inductance and capacitance values for the DC-DC converters have been calculated and Table 4 summarizes these values at different switching frequencies. It illustrating the relationship between the switching frequency and the required component sizing for optimal converter operation.

Operating condition 1: In this case, either an isolated or non-isolated type EV charger module with a linear load is connected to the electrical distribution system individually. The DC-DC converter has been configured with a switching frequency of 10 kHz. The Cuk, Sepic, full-bridge, and flyback converter-based EV chargers have been simulated separately, and the resulting spectrums have been shown in Fig. 6a–d, respectively. Comparing Fig. 6a–d, it has been seen that chargers made with either isolated or non-isolated converters generate supraharmonics more prevalent between the frequency range of 3–6 kHz. The emission band has been seen to slightly varies when the topology of the DC-DC converter is modified. Furthermore, when an EV charger is connected without a linear load, the spectrum of supraharmonic emission is observed to be the same as with the linear load. For each type of charger, the TSHC has been quantified and it has been shown in Fig. 7(a). It is clear from Fig.7(a) that the SEPIC converter-based charger emits more SH than other types of converters. Furthermore, the chargers have been operated with various switching frequency and the results have been examined. It has been identified that when operating at a higher switching frequency, there is no substantial change in the SH emission range of occurrence but an increase in the value of TSHC, as illustrated in Fig. 7 (b). Table 5 illustrates the total harmonic distortion of the charger, obtained in this operating condition.

Operating condition 2: In this operating condition, the consequences of connecting multiple EV chargers one by one to the distribution system have been analysed. All the chargers have been designed with similar topologies and operated at the same switching frequency. In order to accomplish this, CUK converter-based chargers that operate at the same switching frequency have been connected to the grid along with the linear load. When connecting a single charger with the DC fast charging station, the emission band appears between 3 and 6 kHz and peaks around 5 kHz. When charging two EVs simultaneously, the SH emission band is present between 3.5 and 4.5 kHz and is most prominent at 4 kHz. The emission ranges from 3 kHz to 3.5 kHz when three chargers are turned on, with 3.5 kHz acting as the center frequency. In the case of four chargers, the SH emission ranges between 2.5 and 3 kHz, and the concentrated frequency is decreased to approximately 2.9 kHz. The simulation results of the DC fast charging station with 1, 2, 3, and 4 number of chargers are shown in Fig. 8a,d respectively. Simultaneous operation of multiple EV chargers with the same topology connected to the distribution system results in the center frequency of the SH emission shifted from higher to lower frequency range.

Additionally, the same operation has been examined with different converters, and the simulation result for the same has been shown in Fig. 9(a). It has been observed from the simulation results that the supraharmonic frequency has been shifted to a lower value for all four different types of DC-DC converter-based chargers. Further from the results, it is identified that the SEPIC converter-based charger the occurrence of SH emission is in lower frequency range. Figure 9(b) presents the amount of total supraharmonic current for chargers operating at the same switching frequency, as well as for those operating at the different switching frequency.

The results clearly depicts that the supraharmonic emission increases with the number of active devices. Furthermore, research indicates that the frequency range of occurrence of supraharmonic emissions have been reduced when multiple chargers with the same topology are operated simultaneously at the different switching frequency. Table 6 shows the amount of THD obtained when increasing the number of EV chargers activated one by one. It has been identified that when four EV chargers were connected, the THD level increased and reached 27.26%.

Operating condition 3

In this operating condition, four EV distinct chargers are interconnected to the distribution grid simultaneously have been examined. Each charger has been designed to operate at the same switching frequency. Two isolated and two non-isolated DC-DC converters are chosen in this case and operated at a 10 kHz switching frequency. Under this operating condition, the spectrum of the DC fast charging station obtained is shown in Fig. 10(a), which indicates that supraharmonic emission occurs between 1.5 kHz and 3 kHz. Further it has been identified that the peak frequency distortion happens at 2.4 kHz.

According to the simulation results, the incidence of the supraharmonic emission band shifts to a lower frequency band. Also, the amount of TSHC has quantified as 34.73 mA from the simulation results. Comparing the SH emissions from four chargers with the same converters and different converters is shown in Fig. 10(b). It clearly indicates that the TSHC has been reduced when employing different topological converters in the same switching frequency. Also, the THD level is obtained for this configuration as 28.92% which is higher than operating 4 chargers with the same topological converters.

Operating condition 4: In this operating condition, four DC-DC converter topologies operating at four different switching frequencies have been examined for its supraharmonic emission levels. The same configuration which is used to test the condition 3 has been used for this condition alsoFig. e 11(a) shows the spectrum of condition 4 anFig. 11(b) depicts the comparison between TSHC of operating conditions 3 & 4.

The spectrum in Fig. 11(a) indicates that supraharmonic emission in condition 4 occurs in the frequency range of 1.5 kHz to 3 kHz, which is identical as the different converters operating at the same switching frequency. Also, the simulation results shows that the peak distortion is observed below 2.5 kHz. Figure 11(b) illustrates that the supraharmonic level further decreased when employing different topological converters operating in different switching frequency. The amount of THD obtained for this operating condition is 30.20% which is higher than the other three operating conditions.

Summary of the simulation results

The purpose of this study is to investigate and comprehend the behaviour and performance of the suggested system through simulation-based analysis in MATLAB/Simulink. Table 7. provides the summary of the results obtained from the simulation. It clearly indicates that the supraharmonic emission from the EV chargers is influenced by the number of chargers connected to the distribution system, converter topology, and switching frequency.

Finally, the result comparison between the four conditions is shown in Figure 12.

Conclusion

A 320 kW EV fast charging station configuration considering both with and without a three-phase linear load has been proposed in this paper to analyse the SH emission and THD in the distribution system. The complete model is designed by using MATLAB/Simulink/Simscape software. Supraharmonic emission on the distribution system due to the EV fast charger has been analyzed in this work. Four different operating conditions have been implemented and analyzed the level of supraharmonics in the distribution system. The simulation results revealed that the SH emissions from the chargers connected to the distribution system are influenced by the chosen charger topology and the number of chargers activated. Based on the simulation results, it has been concluded that when connecting a larger number of chargers for charging the vehicle simultaneously can be effective due to the reduced range of occurrence of the supraharmonic emission in the distribution system. Further from the simulation results, when all the converters operate in different switching frequency, the THSC has been reduced to a lower value compared to the other operating conditions. However, in this case, the total harmonic distortion increased somewhat compared to the chargers operated at condition 3. Finally, this paper concludes that the supraharmonic emission due to a charging station with a different type of chargers with different switching frequency can effectively mitigate the supraharmonic emission in the distribution system. A hardware prototype will be developed as part of future research in order to strengthen the robustness and applicability of these findings. In addition, the future study of this work is to incorporate various levels of electric vehicle (EV) chargers into the grid simultaneously, as well as examine the harmonic effects caused by their interaction. This investigation will focus on finding supraharmonic distortions caused by various charging levels, analyzing their cumulative impact on grid stability and ensuring optimal power quality.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Srivastava, A., Manas, M. & Dubey, R. K. Electric vehicle integration’s impacts on power quality in distribution network and associated mitigation measures: a review. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science vol. 70 Preprint at (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-023-00193-w

Maroti, P. K., Padmanaban, S., Bhaskar, M. S., Ramachandaramurthy, V. K. & Blaabjerg, F. The state-of-the-art of power electronics converters configurations in electric vehicle technologies. Power Electron. Devices Compon. 1, 100001 (2022).

Ronanki, D., Kelkar, A. & Williamson, S. S. Extreme fast charging technology—prospects to enhance sustainable electric transportation. Energies (Basel) 12, (2019).

Alfalahi, S. T. Y. et al. Supraharmonics in power grid: identification, standards, and measurement techniques. IEEE Access. 9, 103677–103690 (2021).

Rönnberg, S. Propagation of Supraharmonics in the Low Voltage Grid 2 to 150 KHz. (2017).

Waniek Christian, W., Thomas, Myrzik Johanna, M. A., Meyer, J. & Schegner Peter. &. Supraharmonic interactions between multiple devices within different local low-voltage grid structures. International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’18) 1, 316–319 (2018).

Waniek, C., Wohlfahrt, T., Myrzik, J. M. A., Meyer, J. & Schegner, P. Supraharmonic interactions between multiple devices within different local low voltage grid structures. Renew. Energy Power Qual. J. 1, 316–319 (2018).

Thomas, T. & Michael, P. A. A review of high frequency emission in 2-150 kHz range. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 9, 132 (2020).

Frydlewicz, W., Michalec, Ł., Kostyła, P., Kaczorowska, D. & Sikorski, T. Influence of the supply voltage variation on the conducted emission in the frequency range up to 150 khz injected into the power grid by CFL and LED Lamps—Case study. Appl. Sci. 2024. 14, 2590 (2024).

Espín-Delgado, Á., Rönnberg, S., Sudha Letha, S. & Bollen, M. Diagnosis of supraharmonics-related problems based on the effects on electrical equipment. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 195, (2021).

Bollen j, M. H., Rönnberg, S. K., Schwanz, D., Nakhodchi, N. & Ravindran, V. Harmonics and Wind Power Installations. CIRED Conference 20–23 (2021).

Slangen, T., van Wijk, T., Ćuk, V. & Cobben, S. The propagation and interaction of supraharmonics from electric vehicle chargers in a low-voltage grid. Energies (Basel) 13, (2020).

Shmilovitz, D. On the definition of total harmonic distortion and its effect on measurement interpretation. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery 20, (2005).

Rash, A. Harmonics-what are they. how to measure them and how to solve the problem (in connection with Standards. in Proceedings of 19th convention of electrical and electronics engineers in Israel vol. 1 83–86 (1996).

Blooming, T. M., Asheville, E. E., Carolina, N. & Carnovale, D. J. APPLICATION OF IEEE STD 519–1992 HARMONIC LIMITS.

Rönnberg, S. K. et al. On waveform distortion in the frequency range of 2 kHz–150 kHz—Review and research challenges. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 150, 1–10 (2017).

Khokhlov, V., Meyer, J., Grevener, A., Busatto, T. & Ronnberg, S. Comparison of measurement methods for the frequency range 2-150 kHz (Supraharmonics) based on the present standards framework. IEEE Access. 8, 77618–77630 (2020).

Mendes, T. M. et al. Comparative analysis of the measurement methods for the supraharmonic range. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 118, (2020).

Li, K., Zhao, W., Li, S. & Huang, S. Supraharmonics measurement based on colored noise suppressed matrix pencil method. IEEE Access. 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3311258 (2023).

Slangen, T., van Wijk, T., Cuk, V. & Cobben, J. The Harmonic and Supraharmonic Emission of Battery Electric Vehicles in the Netherlands. in International Conference on Smart Energy Systems and Technologies (SEST) 1–6 (2020).

An, Z., Shen, M. & Wang, T. Supraharmonics Measurement Based on Hybrid Online Measurement and Offline Analysis. in 5th International Conference on Energy, Electrical and Power Engineering, CEEPE 2022 1095–1099 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/CEEPE55110.2022.9783359

Salles, R. S., De Oliveira, R. A., Rönnberg, S. K. & Mariscotti, A. Data-driven assessment of VI diagrams for inference on pantograph quantities waveform distortion in AC railways. Comput. Electr. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2024.109730 (2024).

Kuwalek, P., Bracale, A., Sikorski, T. & Rezmer, J. Synchronized approach based on empirical fourier decomposition for accurate assessment of harmonics and specific supraharmonics. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2024.3406850 (2024).

International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2023: Catching up with Climate Ambitions. www.iea.org. (2023).

Andrii & Bosak Alla Bosak & Leonid Kulakovskyi. Impact of EV Chargers on Total Harmonic Distortion in the Distribution System Network. (2019).

International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2022 Securing Supplies for an Electric Future. www.iea.org/t&c/. (2022).

Sudhendu Sinha, J. & Joseph Teja (NITI Aayog). &. Transforming Trucking in India (Pathways to Zero-Emission Truck Deployment). (2022). https://rmi.org/insight/transforming-trucking-in-india/

Prof, Z. & Rather Mr. Angshu Nath, Ms. Dhanuja Lekshmi & Prof. Rangan Banerjee (IIT Bombay & NITI Aayog). Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure and Its Grid Integration in India. (2021).

Khan, W., Ahmad, A. & Ahmad, F. & Saad Alam, M. A Comprehensive Review of Fast Charging Infrastructure for Electric Vehicles. Smart Science vol. 6 256–270 Preprint at (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/23080477.2018.1437323

Ullah, I. et al. Electric vehicles charging infrastructure planning: a review. Int. J. Green. Energy. 21, 1710–1728 (2024).

Singh, A. R. et al. Electric vehicle charging technologies, infrastructure expansion, grid integration strategies, and their role in promoting sustainable e-mobility. Alexandria Eng. J. 105, 300–330 (2024).

Gnann, T. et al. Fast charging infrastructure for electric vehicles: today’s situation and future needs. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 62, 314–329 (2018).

Levinson, R. S. & West, T. H. Impact of public electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 64, 158–177 (2018).

Mariscotti, A. Harmonic and supraharmonic emissions of Plug-In electric vehicle chargers. Smart Cities. 5, 496–521 (2022).

Yousuf, A. K. M., Wang, Z., Paranjape, R. & Tang, Y. An In-Depth exploration of electric vehicle charging station infrastructure: A comprehensive review of challenges, mitigation approaches, and optimization strategies. IEEE Access. 12, 51570–51589 (2024).

Chakraborty, S. et al. DC-DC converter topologies for electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and fast charging stations: state of the Art and future trends. Energies (Basel) 12, (2019).

Geetanjali & Shrivastava, A. DC-DC Converters for Electric Vehicles with Power Quality Improvement. in 5th International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Communication, Computer Technologies and Optimization Techniques, ICEECCOT 2021 - Proceedings 529–535 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEECCOT52851.2021.9707975

Darmawardana, D. et al. Analysis of High Frequency (Supraharmonics)Emissions Caused by Electric Vehicle Charging. 19th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP) 1–6 (2020).

Chen, F. et al. Survey of Harmonic and Supraharmonic Emission of Fast Charging Stations for Electric Vehicles in China and Germany. in CIRED 2021 Conference 1151 (2021).

Grasel, B., Baptista, J., Tragner, M., Leonhartsberger, K. & Keusch, G. Supraharmonic Emissions of a bidirectional electric vehicle charging station - A research methodology based on tests at reconstructed distribution grid. in IEEE 4th International Conference on Power and Energy Applications, ICPEA 2021 51–59 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021). (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPEA52760.2021.9639320

Slangen, T., Uk, V., Cobben, S. & De Jong, E. Characterization of Supraharmonic Emission from High-Power Electric Vehicle Chargers. CIRED workshop on E-mobility and power distribution systems (2022).

Streubel, T., Kattmann, C., Eisenmann, A. & Rudion, K. Characterization of supraharmonic emission from three different electric vehicle charging infrastructures in time and frequency domain. Energies (Basel) 15, (2022).

Slangen, T., Ćuk, V. & Cobben, S. Summation of supraharmonic currents (2–150 kHz) from EV fast charging stations. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 220, (2023).

Grevener, A., Meyer, J., Rönnberg, S., Bollen, M. & Myrzik, J. Survey of supraharmonic emission of household appliances. in CIRED - Open Access Proceedings Journal vol. 2017 870–874Institution of Engineering and Technology, (2017).

Espín-Delgado, A., Rönnberg, S. K. & Bollen, M. H. J. Uncertainties in the quantification of supraharmonic emission: variations over time. Renew. Energy Power Qual. J. 18, 36–41 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Department of Science & Technology, Government of India for financial support vide reference no. DST/WISE-PhD/ET/2023/60 under the ‘WISE Fellowship for Ph.D.’ programme to carry out this research work. The authors would like to acknowledge the SASTRA Deemed to be University, Thanjavur, India for the facilities provided to carry out this research work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Supraja Rajkumar: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Dr. R. Balasubramanian: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.Dr. K Parkavi Kathirvelu: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajkumar, S., Balasubramanian, R. & Kathirvelu, K.P. A comparative analysis of supraharmonic emission by DC fast chargers used for electric vehicle charging. Sci Rep 15, 7992 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92049-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92049-x