Abstract

Urban infrastructure, particularly in ageing cities, faces significant challenges in maintaining building aesthetics and structural integrity. Traditional methods for detecting diseases on building exteriors, such as manual inspections, are often inefficient, costly, and prone to errors, leading to incomplete assessments and delayed maintenance actions. This study explores the application of advanced deep learning techniques to accurately detect diseases on the exterior surfaces of buildings in urban environments, aiming to enhance detection efficiency and accuracy while providing a real-time monitoring solution that can be widely implemented in infrastructure health management. The research implemented a deep learning model that improves feature extraction and accuracy by integrating DenseNet blocks and Swin-Transformer prediction heads, trained and validated using a dataset of 289 high-resolution images collected from diverse urban environments in China. Data augmentation techniques improved the model’s robustness against varying conditions. The proposed model achieved a high accuracy rate of 84.42%, a recall of 77.83%, and an F1 score of 0.81, with a detection speed of 55 frames per second. These metrics demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in accurately identifying complex damage patterns, such as minute cracks, even within noisy urban environments, significantly outperforming traditional methods. This study highlights the potential of deep learning to transform urban maintenance strategies by offering a practical solution for the real-time detection of diseases on building exteriors, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of urban infrastructure monitoring and contributing to improved maintenance practices and timely interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urban infrastructure maintenance is critical to ensuring the safety, functionality, and aesthetics of cities1,2. As urban areas grow and age3, building maintenance becomes increasingly challenging4. Traditional inspection methods, relying heavily on manual labour5,6, are time-consuming, costly, and prone to human error7,8,9,10. These methods also often require access to hard-to-reach areas, posing risks to workers and leading to incomplete assessments6. Given these limitations, there is a pressing need for more efficient, accurate, and scalable inspection methods5,11.

Recent advances in deep learning have provided powerful tools for automating the detection of structural issues12. Deep learning models, particularly those based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are well-suited for image analysis tasks, such as identifying cracks, corrosion, and other forms of damage on building exteriors13. These models can process large volumes of image data, recognising patterns that may indicate structural defects14. Unlike traditional methods that struggle with variability in lighting, angles, and backgrounds, deep learning models learn from diverse datasets15,16, enabling them to adapt to various conditions encountered in real-world environments17,18,19.

One of the most widely used frameworks for object detection in this context is the You Only Look Once (YOLO) algorithm10. Initially developed in 2015, this algorithm introduced a novel approach to object detection by framing it as a single regression problem rather than a multi-stage process9,10. This innovation significantly reduced the computational complexity of object detection, allowing for real-time processing of images20,21. Over the years, several versions of this algorithm have been released, each improving upon the last in terms of performance and capability15,22,23,24,25,26.

This study leverages a specific version of this object detection framework to automate the detection of structural diseases in building exteriors. The goal is to create a system that can quickly and accurately identify issues from images captured by drones or other imaging devices, significantly enhancing the speed and efficiency of building inspections. The choice of this framework is driven by its ability to perform real-time detection, its effectiveness in identifying objects at multiple scales, and its suitability for tasks requiring both speed and accuracy.

However, applying this technology to building inspections is not without challenges. Variability in the appearance of structural defects, influenced by factors such as lighting conditions, weather, and material properties, requires the model to be trained on a diverse dataset that reflects these variations9,17. The potential for false positives and negatives remains a concern, particularly when features like shadows or reflections are misinterpreted as defects27. Addressing these issues requires careful model training, validation, and post-processing techniques to refine predictions28.

The primary objective of this study is to demonstrate the effectiveness of deep learning in automating the detection of structural diseases in building exteriors. By focusing on practical applications, such as integrating this technology with drone-based imaging systems, the research aims to contribute to more efficient and accurate methods of building maintenance. The findings will provide insights into how these advanced technologies can support urban infrastructure management, offering scalable solutions that improve the safety and longevity of buildings.

In summary, this study not only explores the application of deep learning for structural health monitoring but also addresses the challenges associated with deploying these technologies in real-world settings. By overcoming these challenges, the research aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of building inspections, ultimately contributing to safer and more sustainable urban environments.

Literature review

The rapid evolution of deep learning technologies has led to transformative breakthroughs across numerous domains29,30,31, exemplified by a range of pioneering studies currently under review related to this research32,33. These studies, characterised by their diversity in application, collectively highlight the vast potential of deep learning in tackling complex detection and classification challenges through innovative adaptations of neural network architectures34,35.

With the continuous improvement of computer technology and GPU computing power, target recognition technology based on deep learning has been widely used in intelligent transportation, healthcare, and industrial identification36. Represented by the R-CNN algorithm37, the traditional two-stage type target detection algorithm detection process is too cumbersome, which seriously affects the efficiency of target detection, so improving the speed of target detection has become an urgent problem that needs to be solved. One-stage type algorithms came into being, which enhances traditional target detection algorithms need first to train the region proposal network (RPN) network and then train the cumbersome steps of the key region detection network, which greatly improves the operation speed of the target detection model, the most representative of which is the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series of algorithms, the algorithm to improve the strategy is to abstract the detection task as a regression problem, avoiding the previous algorithm to detect the task of the cumbersome operation of the task is completed in two steps38, but the relative accuracy of the corresponding is lost. With the deepening of the research, the YOLO series algorithms have introduced the fifth version, YOLOv5, which has an improvement in speed and accuracy compared with the previous generations, and a total of four variant algorithms have been derived according to the different network depths and widths8,9,10,39.

In 2022, multiple graph learning neural networks (MGLNN) were introduced as a novel semi-supervised learning framework that leverages numerous graph structures to enhance graph data representation and classification40. This approach significantly diverges from traditional methods that predominantly focus on single graph data, offering a comprehensive solution that integrates multiple graph learning with graph neural networks’ representation capabilities. The ingenuity of MGLNN lies in its versatility, accommodating any specific graph neural network (GNN) model to handle multiple graphs, thereby broadening its applicability across various datasets and domains41. The empirical evidence showcases MGLNN’s superiority in semi-supervised classification tasks, marking a significant stride towards exploiting the synergistic potential of multiple graphs in deep learning.

DenseSPH-YOLOv5, another detection model, ventures into infrastructure damage detection, a critical concern for ensuring the safety and longevity of civil structures42. This study enhances feature extraction capabilities by incorporating DenseNet blocks and Swin-Transformer prediction heads and introduces an attention mechanism to refine detection accuracy in complex and noisy environments. Integrating these advanced components into the YOLOv5 framework demonstrates a notable improvement in detection performance, as evidenced by the model’s precision and efficiency on the RDD-2018 dataset. This work represents a pivotal step towards automating damage detection in real-world applications, offering a solution to a traditionally labour-intensive and error-prone task18,43.

Apart from that, the rapid advancement in computational algorithms and their applications across various domains has significantly contributed to addressing complex problems in energy management35, health diagnostics44, and cybersecurity45,46. Notably, integrating optimisation algorithms and machine learning techniques has enhanced efficiency, security, and decision-making processes8,22,25,37,38,47,48,49,50,51,52. This part synthesises findings from recent studies, illustrating the breadth of applications and highlighting the challenges and solutions proposed within these areas.

Several research gaps can be identified and addressed by the proposed technique. Traditional methods for inspecting building exteriors are labour-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to human error, often resulting in misdiagnosis or overlooked damages42,53,54,55. Existing approaches also lack real-time detection capabilities28,47,56, which limits their effectiveness for timely intervention and management. Additionally, most prior research and applications of detection algorithms focus on large-scale public structures, with limited attention to urban environments where building facades are more varied and complex35,43. There is also a need to improve feature extraction and accuracy in these detection algorithms57, especially in settings with high variability in background and lighting. Furthermore, existing models often struggle to generalise across different surface defects, leading to missed detections or false positives in complex scenarios58,59,60.

The proposed technique addresses these gaps using the YOLOv5 detection algorithm, enhanced with DenseNet blocks and Swin-Transformer prediction heads, to improve feature extraction and add an attention mechanism, allowing more accurate detection in complex environments. This approach provides a solution for real-time detection and classification of building surface defects, overcoming the limitations of manual inspections. It also improves generalisation in multi-target and multi-class detection cases, reducing missed detections or false positives. The technique offers a scalable approach that can be applied in diverse urban settings, supporting comprehensive building quality management and structural health monitoring.

Materials and methods

This research utilises literature review, field investigation, and experimental methods to develop and validate a model for real-time detection of exterior building diseases using the YOLOv5 algorithm. A comprehensive review of existing studies from sources such as the China Knowledge Network, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Elsevier Science Direct, ResearchGate, and Scopus was conducted to analyse the current state of research in this field, leading to the selection of the YOLOv5 algorithm for its capability in real-time disease detection.

A dataset was collected using mobile devices in Longhua District, Shenzhen, Longgang District, Shenzhen, Luhe County, Shanwei, and Yuexiu District, Guangzhou, China. These images were captured under various environmental conditions to ensure diversity and robustness in the training data. Permissions for data collection were obtained from property owners, and all procedures adhered to ethical guidelines.

The dataset was manually labelled and enhanced through data augmentation techniques to improve model robustness. The YOLOv5-based disease detection model was trained on the “JiuTian Bison” cloud GPU platform. Model performance was evaluated using precision, recall, F1 score, mean average precision (mAP), and frames per second (FPS). The enhanced dataset and optimised model components demonstrated effective identification, localisation, and classification of exterior surface diseases. Validation using field data confirmed the model’s performance.

Data sources and processing

Specifically, the data used to train the model came from two channels, the Internet and field collection, totalling 495 images, of which a total of 206 images were collected through the Internet keyword search. A total of 289 images were collected in the field using a mobile device, and the image data were obtained in Longhua District, Shenzhen City, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Luhe County, Shanwei City, and Yuexiu District, Guangzhou City in China. Part of the data is shown in Fig. 1.

Since machine learning requires a large amount of data, the dataset needs to be enhanced to boost the data before training the data61. Data enhancement processing is divided into two categories: one is to generate a new image based on the existing image by scaling, panning, rotating, splicing, and transforming the colour61,62; the second is to add noise interference information in the image25, such as adding mosaics or colour blocks to form the interference, to enhance the model’s generalisation ability. This experiment uses the Mosaic data enhancement method before the model training respectively, the collected data for random angle rotation, random ratio cropping, random scaling, multi-image splicing, HSV(hue, saturation, lightness) adjustment, add mosaic and other data enhancement operations, data enhancement schematic shown in Fig. 2.

As for the data labelling phase, this experiment adopts the training strategy of supervised learning, so data labelling is required before inputting data for model training. This research uses Colabeler to annotate the categories and bounding boxes of the collected image data. Colabeler is a tool designed for annotating image data63,64, supporting both category labelling and bounding box annotations65, commonly used in preparing datasets for computer vision tasks63,66. The schematic diagram of data labelling is shown in Fig. 3. The category labelling is divided into two categories, namely, cracks (labelled as “cracks”) and exterior wall damage (labelled as “exterior wall damage”). After the data labelling work was completed, the code was randomly divided into three categories according to the ratio of 8:1:1: training dataset, validation dataset (val), and test dataset (test). To ensure the rigour of the experiment, the validation set is used to validate the model after training the model based on the training set, adjusting the parameters several times to train and obtain multiple models, and then selecting the best-performing model from each model through performance evaluation, and finally testing the model using the test set.

YOLOv5 network model training

For experimental configuration, YOLOv5 network model training consumes a lot of video memory, so the experiment uses the “JiuTian Bison” cloud GPU platform for training and uses Jupyter to write the code and then debug and run it on the server. The configuration of the experiment is shown in Table 1.

Moreover, a hyperparameter is an artificially defined tuning parameter in machine learning whose role is to help train a more scientific and efficient model67, and the hyperparameters of this experiment are shown in Table 2. In this experiment, this research chose the Adam optimiser to dynamically adjust the learning rate at each stage of training, which can accelerate the convergence of the model and quickly obtain the global optimal solution due to the addition of momentum. Machine learning usually adopts annealing training strategy24, that is, use a more extensive learning rate at the beginning of training, and gradually decay the learning rate in training to find the optimal solution as soon as possible, so this experiment sets the initial learning rate to a larger value of 0.01, and uses a learning rate momentum of 0.937 to adjust dynamically to avoid the model from being challenging to converge, and at the same time, in order to prevent overfitting, this experiment also sets the weight decay coefficient, which is 0.0005; due to the use of momentum, it can accelerate the model convergence and obtain the global optimal solution quickly; because of the cloud GPU computing power, its memory can afford a single multi-data training, so this experiment will set the training batch to 16, that is, each training will be 16 pictures data into the network; finally, in order to ensure that the model training effect, this experiment will be set to 300 rounds of training rounds.

Flow chart for the proposed technique based on the YOLOv5 target detection algorithm

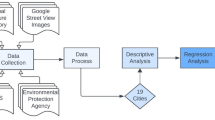

The flowchart for the proposed technique based on the YOLOv5 target detection algorithm outlines the end-to-end process for detecting building surface diseases (Fig. 4). This process involves five main phases: pre-processing, model training, evaluation and optimisation, detection and classification, and real-world deployment.

In the pre-processing phase, mobile devices collect images from diverse urban environments. Data augmentation techniques such as scaling, panning, rotating, and noise addition are applied to enhance model robustness. The images are then manually labelled using software tools to identify categories like cracks and exterior wall damage, then splitting the labelled dataset into training, validation, and test sets.

During the model training phase, this study configures the YOLOv5 algorithm with an overview of its evolution and enhancements over previous versions, including specific architecture setups across layers (Input, Backbone, Neck, and Head) tailored to building disease detection. Hyperparameters like learning rate and batch size are optimised to facilitate efficient model training, and the model is iteratively trained to minimise loss through multiple adjustments of weights and biases.

The evaluation and optimisation phase assesses model performance based on precision, recall, F1 score, mean average precision (mAP), and frames per second (FPS). The model is tested on the validation set for parameter fine-tuning and selection of the best-performing model. It is then evaluated on the test set to confirm its applicability in real-world scenarios.

In the detection and classification phase, incoming images are pre-processed to meet the model’s input requirements. The model predicts bounding boxes around disease-prone areas on building exteriors, with each prediction accompanied by a confidence score. Non-maximum suppression (NMS) is then applied as a post-processing step to refine detection results and minimise overlapping predictions.

Finally, in the real-world deployment phase, the model is adapted for various real-world applications, including integration with drones or mobile devices. Continuous performance monitoring helps identify any need for retraining with updated data. A feedback loop further refines the model by incorporating new data and feedback, supporting ongoing improvement in accuracy and efficiency.

This flowchart thus captures the comprehensive process from data collection to real-world deployment, encompassing continuous performance monitoring and model enhancement to ensure robust detection capabilities. Additional implementation details are provided in the Pseudo Code in Appendix 1.

Results

The Results section systematically evaluates the model’s performance, beginning with a model performance comparison that benchmarks YOLOv5 against other YOLO versions and popular detection models. This comparison highlights YOLOv5’s balance between detection speed and accuracy, making it ideal for real-time building inspection tasks. Following this, quantitative performance metrics such as detection rate, recall, F1 score, mAP, and FPS are discussed, demonstrating the model’s accuracy and efficiency. The section concludes with qualitative results and analysis, showcasing YOLOv5’s effectiveness in real-world scenarios, including its capability to accurately identify building diseases across various multi-target and multi-category detection challenges.

Model performance comparison

The data in Table 3 illustrates the comparative performance of YOLOv5 against other YOLO versions and widely recognised object detection models, sources from13,20,26,31,43,68,69,70,71,72,73. While newer models such as YOLOv7 and YOLOv8 offer marginally higher precision and recall, YOLOv5 achieves a balanced performance with a detection speed of 55 FPS, which is significantly higher than traditional models (e.g., Faster R-CNN at 10 FPS and SSD at 22 FPS), while maintaining high accuracy and recall rates. This balance makes YOLOv5 especially suited for tasks requiring frequent, real-time detection, such as building exterior inspections.

Model performance evaluation

To ensure the scientific nature of the experiments, after the model training is completed, the method of indicator analysis is applied to evaluate the model performance according to the two dimensions of detection accuracy and detection speed, respectively.

Regarding detection accuracy, four indicators, namely, detection rate, recall rate, F1 score51, and mAP, are mainly used to evaluate the model’s accuracy.

-

(1)

Precision. Precision is the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples to the number of positive samples in a specific category of prediction results, which is usually used to evaluate the model’s prediction accuracy71,73. Its calculation formula is shown in Eq. 1.

$$Precision=\frac{TP}{TP+FP}$$(1)In formula (1), TP indicates the positive samples correctly predicted in the prediction results, and FP indicates the incorrect prediction of negative samples as positive in the prediction results.

-

(2)

Recall. Recall is the ratio of the number of correctly predicted positive samples to the number of actual positive samples in the prediction results of a specific category, which is usually used to evaluate the model’s ability to check the whole, and the higher the recall indicates the higher the precision of the detection method52. Its calculation formula is shown in Eq. 2.

$$Recall=\frac{TP}{TP+FN}$$(2)In Eq. (2), TP indicates the positive samples correctly predicted in the detection results, and FN indicates the incorrect prediction that the positive samples are predicted as negative samples in the detection results.

-

(3)

F1 score: The F1 score is the average of the reconciliation of the detection rate and the recall rate, which is a kind of index used to measure the precision of the dichotomous classification model in statistics74, which takes into account the precision rate and the recall rate of the model, and takes the value of 0–1, and the closer the value is to 1, which represents the better the results of the model. Its calculation is shown in Eq. 3.

$$F1score=\frac{2\times Precision\times Recall}{Precision+Recall}$$(3)Equation (3) Prescision denotes the check accuracy and recall rates.

-

(4)

mAP@0.5 (mean Average Precision, loU = 0.5). mAP@0.5 sets the threshold of lOU to 0.5 and then calculates the average detection rate of each type of target, which is used to represent the overall detection effect of the model and its calculation formula is shown in Eq. 4.

$$mAP=\frac{1}{n}\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}A{P}_{i}$$(4)

In Eq. (4), AP is the area enclosed by the plotted coordinate axes, indicating the average accuracy of each category, and n is the number of categories.

The iterative training of the model initially exhibits oscillations in the performance indicators, generally showing an upward trend. After 265 training iterations, the model stabilizes, allowing for the output to be visualized in a line chart, as depicted in Fig. 5, illustrating metrics such as accuracy, recall, F1 score, and mAP@0.5. After iterative training, the model’s detection rate reaches 84.42%, the recall rate reaches 77.83%, and the F1 score is 0.81, mAP@0.5yields 82.56%, which shows that the model has considerable precision when trained with small samples, and can be applied to the task of inspecting the exterior surfaces of buildings in real-world scenarios by increasing the dataset for training in the future.

In terms of detection speed, Frame Per Second (FPS) is used to evaluate the detection efficiency of the model, and the FPS value is found by calculating the total detection time of a certain number of test images and then averaging them75. Using 1429 images fed into the trained network model for detection, a total of 25.43 s, calculated that the model detection speed of 55 frames per second, that is, 55 images per second, can be detected; in summary, it can be learned that the model can be trained to achieve the real-time detection of the external surface of the building disease, the future can be mounted on the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) and other equipment using sensors for the detection of building disease work.

Detection results and analysis

The images of building facades collected in the field are passed into the trained model for detection, and some of the detection results are shown in Fig. 6. The rectangular anchor box indicates the range and location of the building facade disease, the label above the rectangular anchor box is the category to which the building facade disease belongs, and the value next to the label is the confidence score, which indicates the credibility of the detection results. It can be seen that the model has a specific recognition ability for building exterior surface diseases in single-target detection scenarios. Cracks and exterior wall damage can be detected and categorised, and the bounding box accurately locates the range and location of building exterior surface diseases in the image. The model can also recognise building exterior surface diseases at a long distance; the detection results also show the model has a strong anti-jamming ability. The detection results also show that the model has a strong anti-interference ability, and cracks obscured by similarly shaped objects, such as electric wires and tree branches, can also be recognised without false detection.

To further validate the model’s ability to detect diseases on the exterior surface of the building, this paper also sets up a multi-target detection scene and a multi-category target detection scene. The multi-target detection scene detection results are shown in Fig. 7, which shows that when there are multiple building diseases in the image, the model can also locate and classify the diseases in a short time. However, in the multi-target detection scene of the exterior wall damage, the model generalisation ability is general, which shows that the exterior wall damage is confused with the background of a similar colour, leading to misdetection and the whole piece of tile falling off this kind of regular shape of the exterior wall damage is easy to miss detection. This is because the building’s facade can be easily damaged. The reason for this is that the building facade is more complex than the surface background of a single material, more interference information76, and the building facade damage has a variety of morphology; adding more types of facade damage image data for training will be able to solve this problem.

In the actual detection scene, some cracks and exterior wall damages have symbiosis, and their boundaries are sticky. Some exterior wall damages are developed from cracks, and there is a certain degree of similarity between them in colour, which makes it difficult to distinguish between them. The results of this model are shown in Fig. 8, which shows that the model can complete the task of classifying diseases on the exterior surface of the building in the multi-category detection scene. When the cracks are symbiotic with the damage on the exterior wall, the model can use the rectangular anchor box with different colours to separate the boundaries of the two to achieve the localisation of the various categories of diseases in the image.

Discussion

This study presents an advancement in applying deep learning techniques for detecting structural diseases in building exteriors. By employing the YOLOv5 model, the research demonstrates an approach to a traditionally labour-intensive and error-prone task. Integrating advanced computational methods enhances the accuracy and efficiency of disease detection, paving the way for innovative strategies in urban maintenance.

The YOLOv5-based model developed in this study achieved results, including an accuracy rate of 84.42%, a recall rate of 77.83%, a class average precision of 82.56%, and an F1 score of 0.81, with the capability to process 55 images per second. These metrics represent a substantial improvement over manual inspection methods, showcasing the model’s ability to deliver high-precision real-time detection. Incorporating DenseNet blocks and Swin-Transformer prediction heads has further improved the model’s feature extraction capabilities, particularly in accurately detecting minute cracks and complex damage patterns in noisy urban environments.

The application of this model to building disease detection underscores its adaptability and scalability across various urban settings, indicating its potential for widespread implementation in infrastructure maintenance and safety inspections. The findings highlight the potential of deep learning technologies to revolutionise urban infrastructure maintenance, allowing municipalities and property management companies to allocate resources more efficiently and ensure timely repairs, thereby extending the lifespan of buildings.

Moreover, YOLOv5 offers a compelling combination of efficiency and adaptability10,. Unlike more complex newer models, YOLOv5 retains a streamlined architecture that reduces computational complexity and memory usage, making it ideal for deployment on resource-constrained devices such as drones, embedded systems, and mobile platforms42. This simplification enhances portability and flexibility, allowing for broader and more cost-effective deployment in various urban maintenance scenarios.

The YOLOv5 model also exhibits strong robustness in complex environments, particularly in urban settings where it effectively detects fine-grained features such as tiny cracks and subtle damage patterns10. Its adaptability to diverse backgrounds and materials is crucial for building exterior disease detection, where variability is often high. Furthermore, YOLOv5’s general-purpose nature makes it suitable for a wide range of object detection tasks, from infrastructure monitoring to disaster management, without frequent retraining or fine-tuning, thus reducing development and maintenance costs.

In contrast to newer models like YOLOv7 and YOLOv8, which may offer marginally higher performance metrics72,73,77,78,79, YOLOv5 excels in scenarios where a balance of speed, accuracy, and resource efficiency is paramount. Its architecture facilitates rapid deployment, ease of use, and consistent performance across various environments, making it particularly valuable for large-scale, real-time urban infrastructure monitoring and other related applications. The model’s ability to deliver high detection accuracy with lower computational demands ensures that it remains a practical choice for cities and organisations aiming to implement efficient and scalable inspection processes.

Additionally, the model’s effectiveness in real-time applications reduces the reliance on manual inspections, which are often time-consuming, costly, and prone to human error. By automating the detection process, YOLOv5 significantly enhances the reliability and speed of building inspections. It is a valuable tool for municipalities and property managers, especially in ageing urban areas where timely detection and intervention are critical to preventing further deterioration and reducing maintenance costs.

As for weaknesses and limitations, one of the notable limitations of the proposed YOLOv5-based model is its generalisation ability in highly diverse urban environments. While the model demonstrates robust performance in detecting common diseases like cracks and exterior wall damage, its accuracy may vary across architectural styles and materials that are not well-represented in the training dataset. This variation can lead to increased false positives or negatives in scenarios where the exterior surface features significantly differ from those the model has been trained on.

Additionally, the model’s performance is contingent upon the quality and resolution of input images. In real-world scenarios, images captured under suboptimal conditions (e.g., low light, adverse weather, or varying distances) may impede the model’s ability to detect and classify diseases accurately. This sensitivity underscores the need for high-quality data collection protocols, which may not always be feasible in practical applications.

Another limitation involves the computational resources required for processing large datasets and maintaining real-time detection capabilities. While the model is optimised for efficiency, deploying it on lower-end hardware or integrating it into mobile platforms for on-site inspections may present challenges. This aspect is crucial for scalability and broader adoption in building maintenance workflows.

Regarding potential areas for improvement, future work could explore incorporating more diverse image data to enhance the model’s generalisation capabilities, covering a broader spectrum of building styles, materials, and conditions80,81,82. Employing advanced data augmentation techniques that simulate various environmental factors could also improve the model’s resilience to real-world variations10,36,61,70,83.

Improving the model’s robustness to suboptimal image conditions could involve integrating additional pre-processing steps or leveraging more sophisticated image enhancement algorithms53,71,84,85,86,87,88. Exploring the potential of recent advancements in low-light image processing and adverse weather condition adaptation could yield significant improvements in detection accuracy under challenging conditions.

Addressing the computational resource limitation necessitates further optimisation of the model’s architecture for deployment on edge devices57,89,90. Research into model quantisation, pruning, and developing lightweight versions of the YOLOv5 algorithm could facilitate more efficient real-time processing and expand the model’s applicability to mobile or drone-based inspection systems91.

While the proposed YOLOv5-based model represents a significant advancement in detecting diseases on the exterior surfaces of buildings, acknowledging these limitations and pursuing targeted improvements will be essential for realising its full potential. By addressing these areas, future model iterations may achieve greater accuracy, robustness, and accessibility, further contributing to urban maintenance and safety inspections.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the efficacy of utilising deep learning techniques in detecting diseases on the exterior surfaces of buildings, offering a solution to a traditionally labour-intensive and error-prone task. By integrating advanced computational methods, this approach significantly enhances the accuracy and efficiency of disease detection, paving the way for innovative strategies in urban maintenance.

The YOLOv5-based model developed in this study achieved results, including an accuracy rate of 84.42%, a recall rate of 77.83%, a class average precision of 82.56%, and an F1 score of 0.81, with the capability to process 55 images per second. These metrics substantially improve manual inspection methods, showcasing the model’s ability to deliver high-precision, real-time detection. Incorporating DenseNet blocks and Swin-Transformer prediction heads has further improved the model’s feature extraction capabilities, particularly in accurately detecting minute cracks and complex damage patterns in noisy urban environments.

The application of this model to building disease detection underscores its adaptability and scalability across various urban settings, indicating its potential for widespread implementation in infrastructure maintenance and safety inspections. The findings of this study highlight the potential of deep learning technologies to revolutionise urban infrastructure maintenance, allowing municipalities and property management companies to allocate resources more efficiently and ensure timely repairs, thereby extending the lifespan of buildings.

Future research will explore the proposed model’s scalability across different urban landscapes and architectural styles. Efforts will also be directed toward refining the model for deployment on edge devices and drones, enabling on-site inspections and real-time monitoring. Acknowledging the model’s limitations in handling diverse environments and suboptimal imaging conditions, subsequent studies will enhance its generalisation capabilities by expanding the training dataset with more varied images and employing more sophisticated data augmentation techniques to simulate real-world conditions.

Data availability

The data relevant to this paper have been included within the Supporting Information files. Further information may be obtained from the first author (You Chen, chenyou13277035613@gmail.com) with the university’s consent (Universiti Sains Malaysia).

References

Yang, S. et al. Assessing the impacts of rural depopulation and urbanization on vegetation cover: Based on land use and nighttime light data in China, 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 159, 111639 (2024).

Wu, X. & Zhang, Y. Coupling analysis of ecological environment evaluation and urbanization using projection pursuit model in Xi’an, China. Ecol. Indic. 156, 111078 (2023).

Chen, Y., Yin, X. & Lyu, C. Circular design strategies and economic sustainability of construction projects in china: The mediating role of organizational culture. Sci. Rep. 14, 7890 (2024).

Wang, Y., Zhao, N., Chen, K. & Wu, C. Intensification of compound temperature extremes by rapid urbanization under static and dynamic Urban-rural division: A comparative case study in Hunan Province, Central-South China. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168325 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Return migration and in-situ urbanization of 79 migrant sending counties in China: Characteristic and driving factors. J. Rural Stud. 104, 103155 (2023).

Létourneau, V. et al. Hunting for a viral proxy in bioaerosols of swine buildings using molecular detection and metagenomics. J. Environ. Sci. 148, 69–78 (2025).

Zhang, P. & Li, D. EPSA-YOLO-V5s: A novel method for detecting the survival rate of rapeseed in a plant factory based on multiple guarantee mechanisms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 193, 106714 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Underwater scallop recognition algorithm using improved YOLOv5. Aquac. Eng. 98, 102273 (2022).

Guo, G. & Zhang, Z. Road damage detection algorithm for improved YOLOv5. Sci. Rep. 12, 15523 (2022).

Xiang, W. et al. Road disease detection algorithm based on YOLOv5s-DSG. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2737315/v1 (2023) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2737315/v1.

Liu, Q. et al. Porphyrin/phthalocyanine-based porous organic polymers for pollutant removal and detection: Synthesis, mechanisms, and challenges. Environ. Res. 239, 117406 (2023).

Sarkar, C., Gupta, D., Gupta, U. & Hazarika, B. B. Leaf disease detection using machine learning and deep learning: Review and challenges. Appl. Soft Comput. 145, 110534 (2023).

Yi, Z., Yongliang, S. & Jun, Z. An improved tiny-yolov3 pedestrian detection algorithm. Optik 183, 17–23 (2019).

Fergusson, M. et al. Validation of a multiplex-tandem RT-PCR for the detection of bovine respiratory disease complex using Scottish bovine lung samples. Vet. J. 303, 106058 (2024).

Wang, C.-Y. & Liao, H.-Y. M. YOLOv1 to YOLOv10: The fastest and most accurate real-time object detection systems. http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.09332 (2024).

Bochkovskiy, A., Wang, C.-Y. & Liao, H.-Y. M. YOLOv4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.10934 (2020).

Cong, P. et al. A visual detection algorithm for autonomous driving road environment perception. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 133, 108034 (2024).

Wang, T.-W. et al. Brain metastasis tumor segmentation and detection using deep learning algorithms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 190, 110007 (2024).

Gowthami, S., Reddy, R. V. S. & Ahmed, M. R. Exploring the effectiveness of machine learning algorithms for early detection of Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Meas. Sens. 31, 100983 (2024).

Ma, W., Guan, Z., Wang, X., Yang, C. & Cao, J. YOLO-FL: A target detection algorithm for reflective clothing wearing inspection. Displays 80, 102561 (2023).

Muksit, A. A. et al. YOLO-Fish: A robust fish detection model to detect fish in realistic underwater environment. Ecol. Inform. 72, 101847 (2022).

Luo, X., Wu, Y. & Wang, F. Target detection method of UAV aerial imagery based on improved YOLOv5. Remote Sens. 14, 5063 (2022).

Zhou, K. et al. Evaluation of BFRP strengthening and repairing effects on concrete beams using DIC and YOLO-v5 object detection algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 411, 134594 (2024).

Liu, X., Wang, T., Yang, J., Tang, C. & Lv, J. MPQ-YOLO: Ultra low mixed-precision quantization of YOLO for edge devices deployment. Neurocomputing 574, 127210 (2024).

Li, G., Song, Z. & Fu, Q. A new method of image detection for small datasets under the framework of YOLO network. In 2018 IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC) 1031–1035 (IEEE, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/IAEAC.2018.8577214.

Wang, C.-Y., Yeh, I.-H. & Liao, H.-Y. M. YOLOv9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. http://arxiv.org/abs/2402.13616 (2024).

Chen, H. & Guan, J. Teacher-student behavior recognition in classroom teaching based on improved YOLO-v4 and internet of things technology. Electronics 11, 3998 (2022).

Zhou, Z., Yan, L., Zhang, J. & Yang, H. Real-time tunnel lining crack detection based on an improved You Only Look Once version X algorithm. Georisk. Assess. Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohazards 17, 181–195 (2023).

Ji, S.-J., Ling, Q.-H. & Han, F. An improved algorithm for small object detection based on YOLO v4 and multi-scale contextual information. Comput. Electr. Eng. 105, 108490 (2023).

Situ, Z. et al. A transfer learning-based YOLO network for sewer defect detection in comparison to classic object detection methods. Dev. Built Environ. 15, 100191 (2023).

Alruwaili, M., Siddiqi, M. H., Atta, M. N. & Arif, M. Deep learning and ubiquitous systems for disabled people detection using YOLO models. Comput. Hum. Behav. 154, 108150 (2024).

Liu, J. & Jin, Y. A comprehensive survey of robust deep learning in computer vision. J. Autom. Intell. 2, 175–195 (2023).

Venugopal, V., Nath, M. K., Joseph, J. & Das, M. V. A deep learning-based illumination transform for devignetting photographs of dermatological lesions. Image Vis. Comput. 142, 104909 (2024).

Behrad, F. & Saniee Abadeh, M. An overview of deep learning methods for multimodal medical data mining. Expert Syst. Appl. 200, 117006 (2022).

Jimenez-Mesa, C. et al. Applications of machine learning and deep learning in SPECT and PET imaging: General overview, challenges and future prospects. Pharmacol. Res. 197, 106984 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Dig information of nanogenerators by machine learning. Nano Energy 114, 108656 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Weed identification in soybean seedling stage based on optimized faster R-CNN algorithm. Agriculture 13, 175 (2023).

Liu, J. & Wang, X. Tomato diseases and pests detection based on improved Yolo V3 convolutional neural network. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 898 (2020).

Liang, H. & Song, T. Lightweight marine biological target detection algorithm based on YOLOv5. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1219155 (2023).

Jiang, B., Chen, S., Wang, B. & Luo, B. MGLNN: Semi-supervised learning via multiple graph cooperative learning neural networks. Neural Netw. 153, 204–214 (2022).

Sutanto, H. Transforming clinical cardiology through neural networks and deep learning: A guide for clinicians. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 49, 102454 (2024).

Roy, A. M. & Bhaduri, J. DenseSPH-YOLOv5: An automated damage detection model based on DenseNet and swin-transformer prediction head-enabled YOLOv5 with attention mechanism. Adv. Eng. Inform. 56, 102007 (2023).

Ren, R. et al. FPG-YOLO: A detection method for pollenable stamen in ‘Yuluxiang’ pear under non-structural environments. Sci. Hortic. 328, 112941 (2024).

Chakraborty, C., Bhattacharya, M., Pal, S. & Lee, S.-S. From machine learning to deep learning: Advances of the recent data-driven paradigm shift in medicine and healthcare. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 7, 100164 (2024).

Aljehane, N. O. et al. Golden jackal optimization algorithm with deep learning assisted intrusion detection system for network security. Alex. Eng. J. 86, 415–424 (2024).

Dehghani, M. et al. Blockchain-based securing of data exchange in a power transmission system considering congestion management and social welfare. Sustainability 13, 90 (2020).

Niu, Y., Lu, M., Liang, X., Wu, Q. & Mu, J. YOLO-plum: A high precision and real-time improved algorithm for plum recognition. PLoS ONE 18, e0287778 (2023).

Sanborn, A. N., Griffiths, T. L. & Navarro, D. J. Rational approximations to rational models: Alternative algorithms for category learning. Psychol. Rev. 117, 1144–1167 (2010).

Mazen, F. M. A., Seoud, R. A. A. & Shaker, Y. O. Deep learning for automatic defect detection in PV modules using electroluminescence images. IEEE Access 11, 57783–57795 (2023).

Veeranampalayam Sivakumar, A. N. et al. Comparison of object detection and patch-based classification deep learning models on mid- to late-season weed detection in UAV imagery. Remote Sens. 12, 2136 (2020).

Tan, L., Huangfu, T., Wu, L. & Chen, W. Comparison of RetinaNet, SSD, and YOLO v3 for real-time pill identification. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 21, 324 (2021).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 10, e0118432 (2015).

Cai, Y. et al. Rapid detection of fish with SVC symptoms based on machine vision combined with a NAM-YOLO v7 hybrid model. Aquaculture 582, 740558 (2024).

Ahmed, A., Imran, A. S., Manaf, A., Kastrati, Z. & Daudpota, S. M. Enhancing wrist abnormality detection with YOLO: Analysis of state-of-the-art single-stage detection models. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 93, 106144 (2024).

Abuhassna, H. et al. Development of a new model on utilizing online learning platforms to improve students’ academic achievements and satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 17, 38 (2020).

Sandhya, & Kashyap, A. A novel method for real-time object-based copy-move tampering localization in videos using fine-tuned YOLO V8. Forensic Sci. Int. Digit. Investig. 48, 301663 (2024).

Cheung, T., Schiavon, S., Parkinson, T., Li, P. & Brager, G. Analysis of the accuracy on PMV–PPD model using the ASHRAE global thermal comfort database II. Build. Environ. 153, 205–217 (2019).

Zhang, B., Li, Z.-G., Tong, P. & Sun, M.-J. Non-uniform imaging object detection method based on NU-YOLO. Opt. Laser Technol. 174, 110639 (2024).

Razmjooy, N., Sheykhahmad, F. R. & Ghadimi, N. A hybrid neural network—world cup optimization algorithm for melanoma detection. Open Med. 13, 9–16 (2018).

Ghadimi, N. A hybrid neural network-gray wolf optimization algorithm for melanoma detection. Biomed. Res. 28, 3408–3411 (2017).

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 6, 60 (2019).

Kim, J.-H., Kim, N., Park, Y. W. & Won, C. S. Object detection and classification based on YOLO-V5 with improved maritime dataset. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 10, 377 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Detecting occluded and dense trees in urban terrestrial views with a high-quality tree detection dataset. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–12 (2022).

Alrasheed, N. et al. Evaluation of deep learning techniques for content extraction in Spanish colonial notary records. In 23–30 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3475720.3484443

Wang, C. et al. A systematic method to develop three dimensional geometry models of buildings for urban building energy modeling. Sustain. Cities Soc. 71, 102998 (2021).

Qu, E. Z., Jimenez, A. M., Kumar, S. K. & Zhang, K. Quantifying nanoparticle assembly states in a polymer matrix through deep learning. Macromolecules 54, 3034–3040 (2021).

Stefenon, S. F., Seman, L. O., Klaar, A. C. R., Ovejero, R. G. & Leithardt, V. R. Q. Hypertuned-YOLO for interpretable distribution power grid fault location based on EigenCAM. Ain Shams Eng. J. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2024.102722 (2024).

Tan, L., Lv, X., Lian, X. & Wang, G. YOLOv4_Drone: UAV image target detection based on an improved YOLOv4 algorithm. Comput. Electr. Eng. 93, 107261 (2021).

Tang, Z., Lu, J., Chen, Z., Qi, F. & Zhang, L. Improved Pest-YOLO: Real-time pest detection based on efficient channel attention mechanism and transformer encoder. Ecol. Inform. 78, 102340 (2023).

Sun, Y., Zheng, W., Du, X. & Yan, Z. Underwater small target detection based on YOLOX combined with MobileViT and double coordinate attention. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 11, 1178 (2023).

Zhu, L., Li, X., Sun, H. & Han, Y. Research on CBF-YOLO detection model for common soybean pests in complex environment. Comput. Electron. Agric. 216, 108515 (2024).

Ajitha Gladis, K. P., Madavarapu, J. B., Raja Kumar, R. & Sugashini, T. In-out YOLO glass: Indoor-outdoor object detection using adaptive spatial pooling squeeze and attention YOLO network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 91, 105925 (2024).

Tian, Y. et al. MD-YOLO: Multi-scale Dense YOLO for small target pest detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 213, 108233 (2023).

Liu, T., Zhang, H., Long, H., Shi, J. & Yao, Y. Convolution neural network with batch normalization and inception-residual modules for Android malware classification. Sci. Rep. 12, 13996 (2022).

Benenson, R., Mathias, M., Timofte, R. & Van Gool, L. Pedestrian detection at 100 frames per second. In 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2903–2910 (IEEE, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2012.6248017.

Tang, P., Huber, D., Akinci, B., Lipman, R. & Lytle, A. Automatic reconstruction of as-built building information models from laser-scanned point clouds: A review of related techniques. Autom. Constr. 19, 829–843 (2010).

Jia, Y., Fu, K., Lan, H., Wang, X. & Su, Z. Maize tassel detection with CA-YOLO for UAV images in complex field environments. Comput. Electron. Agric. 217, 108562 (2024).

Zhang, Q., Li, Y., Zhang, Z., Yin, S. & Ma, L. Marine target detection for PPI images based on YOLO-SWFormer. Alex. Eng. J. 82, 396–403 (2023).

Li, Q., Shao, Z., Zhou, W., Su, Q. & Wang, Q. MobileOne-YOLO: Improving the YOLOv7 network for the detection of unfertilized duck eggs and early duck embryo development - a novel approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 214, 108316 (2023).

Shi, Q. et al. Manipulator-based autonomous inspections at road checkpoints: Application of faster YOLO for detecting large objects. Def. Technol. 18, 937–951 (2022).

Wang, S. & Hao, X. YOLO-SK: A lightweight multiscale object detection algorithm. Heliyon 10, e24143 (2024).

Koga, S., Hamamoto, K., Lu, H. & Nakatoh, Y. Optimizing food sample handling and placement pattern recognition with YOLO: Advanced techniques in robotic object detection. Cognit. Robot. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogr.2024.01.001 (2024).

Dulf, E.-H., Bledea, M., Mocan, T. & Mocan, L. Automatic detection of colorectal polyps using transfer learning. Sensors 21, 5704 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. Ship imaging trajectory extraction via an aggregated you only look once (YOLO) model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 130, 107742 (2024).

Wu, L. et al. The YOLO-based multi-pulse lidar (YMPL) for target detection in hazy weather. Opt. Lasers Eng. 177, 108131 (2024).

Oreski, G. YOLO*C—adding context improves YOLO performance. Neurocomputing 555, 126655 (2023).

Kang, L., Lu, Z., Meng, L. & Gao, Z. YOLO-FA: Type-1 fuzzy attention based YOLO detector for vehicle detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 237, 121209 (2024).

Li, H., Wu, D., Zhang, W. & Xiao, C. YOLO-PL: Helmet wearing detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv4. Digit. Signal Process. 144, 104283 (2024).

Hakim, M., Omran, A. A. B., Ahmed, A. N., Al-Waily, M. & Abdellatif, A. A systematic review of rolling bearing fault diagnoses based on deep learning and transfer learning: Taxonomy, overview, application, open challenges, weaknesses and recommendations. Ain Shams Eng. J. 14, 101945 (2023).

Ai, D., Jiang, G., Lam, S.-K., He, P. & Li, C. Computer vision framework for crack detection of civil infrastructure—A review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 117, 105478 (2023).

Kheddar, H., Hemis, M., Himeur, Y., Megías, D. & Amira, A. Deep learning for steganalysis of diverse data types: A review of methods, taxonomy, challenges and future directions. Neurocomputing 581, 127528 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C.: Conceptualisation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualisation, Writing original draft. D.L.: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Li, D. Disease detection on exterior surfaces of buildings using deep learning in China. Sci Rep 15, 8564 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92112-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92112-7