Abstract

Water pollution from the industrial dyes is a serious hazard to ecosystems, and addressing this issue is a significant challenge. To address these issues, we are fabricated BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02 to 0.06) by sol-gel auto-ignition (SGA) technique. Several characterizations were used to scrutinize the structural, optical, photocatalytic, and magnetic traits of the produced samples. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) of the sample revels the hexagonal crystal structure. The field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) of both samples reveal the existence of agglomerated grains showing hexagonal shapes. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses confirm the oxidation state of every element present in the synthesized nanomaterials. The specific surface area was found to be 1.069 m2/g for BDF1 and 1.466 m2/g for BDF3. The band gap of the BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 samples are found 2.16, 2.12, and 1.99 eV. The photocatalytic efficacy of the catalysts was examined by removal of the CR in natural light. A notable degradation efficiency of 89.29% are achieved by the BDF3 catalyst within 90 minutes under natural sunlight irradiation. The results demonstrate a straightforward and efficient approach for producing photocatalytic materials that are highly effective for the elimination of dye pollutants in wastewater treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pollution of the aquatic ecosystem has escalated into a progressively critical issue. As a consequence of the extensive advancement of the pharmaceutical1, agricultural, and textiles sectors2, a plethora of chemical substances, including antibiotics, pesticides, and dyes infiltrates aquatic habitat3. Synthetic dyes are frequently undervalued as the environmental pollutants because of their minimal concentrations present within aquatic ecosystems4. The Sustainable Development Goal 6 emphasises the importance of sanitation and clean water for improving human health, promoting social growth and economic, and protecting environments5. Their presence can be attributed to extensive production and numerous applicative domains. Dyes are extensively utilized across various industries, including textile, food, tannery, and cosmetic manufacturing, with additional applications in the pharmaceutical sectors6,7. Globally, around 10,000 different textile dyes are produced, amounting to over 700,000 tons annually. Among these, the azo, anthraquinone, and phthalocyanine dyes are particularly significant in the textile industry8. In terms of human health, past research by environmentalists and ecotoxicologists has shown that consuming contaminated water with synthetic dyes can lead to the genotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic effects. Dyes are generally classified into three categories: anionic, non-ionic, and cationic named as methylene blue9, crystal violet10, methyl orange11, Rhodamine B12. This is one of the reasons that the environmental contaminations are widespread use of direct dyes, especially azo dyes, which greatly contaminate streams and surface runoffs. One of the most used synthetic anionic azo dye is congo red (CR), also known by its scientific name benzidinediazo-bis-1-naphthylamine-4-sulfonic acid13. This dye contains the 2-azo (-N = N-) chromophores and SO3H attached to benzene structures and is also known as an acidic diazo dye. The molecular structure of CR is linearly symmetrical, featuring a hydrophobic core of two phenyl rings linked by a diazo bond. These phenyl rings are further connected to the two charged naphthalene units with sulfonic and amino groups. CR is water-soluble and exhibits a distinct color in aqueous solution due to its azo structure. In a basic medium, it appears red, while in an acidic medium, it turns blue, as it is a diazo dye. Upon the cleavage of its azo bonds, the CR can produce amine derivatives, such as benzidine. CR is commonly used in industries, printing, textiles, paper, leather, cosmetics, and pulp. Notably, CR possesses excellent traits including, the thermal, optical, and chemical stability because of the persistent aromatic composition. This feature emphasizes the pressing need to address its environmental impact, as does its detrimental impacts on aquatic wildlife and human health. CR negatively impacts human health, causing a range of diseases that can be life-threatening due to its cytotoxic carcinogenic, and mutagenic traits. It particularly affects organs such as the skin, eyes, reproductive and respiratory systems. Benzidine, a toxic metabolite of CR, triggers allergic reactions and is a known carcinogen, specifically linked to bladder cancer, where it binds covalently to cellular macromolecules, inhibiting their activity. The aromatic rings of this dye make them tough to natural degradation, allowing them to persist in the environment for extended periods, causing harmful effects on both fauna and flora. Therefore, treating water contaminated with CR is very crucial.

Various conventional dye removal techniques have been proposed to eliminate the CR dye from the water, like coagulation–flocculation, adsorption, ion exchange, ultrasound irradiation, photocatalysis14, and mineralisation15. Most of the physical and biological processes, exhibit limitations in their capacity to eradicate all types of dyes, particularly reactive dyes16. These specific dyes possess multiple functional groups, which facilitate the formation of robust bonds with the substrate, thereby impeding the degradation process. Consequently, an advanced oxidation technique is employed to eliminate the dyes that resist removal through conventional approaches17,18. Within the framework of Advance oxidation process (AOP), the photocatalysis is a potential technique for the removal of toxins via oxidative mechanisms. In the photocatalytic process, the application of light sources and catalysts is instrumental in enhancing the degradation kinetics of the organic pollutants19. Photocatalysis is generally classified into 2 types: (1) Homogeneous photocatalysis, where both the reactant and catalyst exist in the identical phase, and in heterogeneous, the reactant and catalyst are in different phases. Heterogeneous photocatalysis is beneficial for dye removal in the wastewater due to its numerous benefits20. One key advantage is the ease of recovering and reusing photocatalysts, making heterogeneous systems more cost-effective and sustainable for the large-scale use21. Moreover, the heterogeneous photocatalysis offers higher efficiency and selectivity, as the solid catalyst interacts directly with the dye molecules, leading to more complete degradation and fewer side reactions22. Additionally, heterogeneous photocatalysis reduces the risk of effluent contamination with catalyst residues, helping to meet environmental regulatory standards23.

Ferrites have received substantial interest due to their diverse uses and types across various technological and industrial sectors. They are divided into four main categories: hexagonal (MFe12O19), garnet (M3Fe5O12), orthogonal (MFeO3), and spinel (AB2O4), where M typically represents elements like Sr, Pb or Ba24. Among these, the hexaferrites have garnered particular interest for applications in the sensors, biomedical fields, catalysis, and permanent magnets, primarily due to their remarkable magnetic and optical characteristics. Hexaferrites have been extensively studied worldwide because of functional roles based on their magnetic properties. Today, hexaferrites are widely acknowledged for their effectiveness in the various wastewater treatment processes, particularly for the pollutant removal through the photocatalysis25. As catalysts, the hexaferrites are highly effective owing to their ease of regeneration, stability, affordable, and ability to absorb the visible light with appropriate band gap (1.1 to 2.3 eV)26. The magnetic nature of the barium hexaferrite also helps in its easy recovery from the system. This helps in reducing the residual concentration of material in the treated water. This property makes the hexaferrite an attractive option for photocatalytic degradation. Moreover, in a study done by Alvino et al. (2020), they found that presence of barium hexaferrite has a little impact on the microbial growth, which means that the possibility of these materials to disturb the microbial balance in environment is low. But they also found that the barium hexaferrite have some adverse toxic impact on C. elegans27. This means that at higher concentration the barium hexaferrite might have some adverse effect but this problem can be countered by utilizing its magnetic nature and removing it from the treated water28.

In recent years, the photocatalytic properties of M-type hexaferrite have garnered significant attention, particularly through the adding of Ba2+ and Fe3+ ions by various divalent and trivalent cations. Incorporating rare earth elements can altering the photocatalytic traits of nanoferrites. The unique traits of these elements, like their larger ionic radii and localized 4f electrons, contribute to the enhanced photocatalytic performance. According to the literature, doping hexaferrites with rare earth elements has been shown to degrade the various dyes effectively. In an analysis by Bibi et al., Ba1 − xNdxFe12−yCuyO19 was produced using a micro-emulsion technique. The magnetic behaviour of the prepared material shows easily remove and reuse in photocatalysis. Photocatalytic activities (PCA) of both the samples were compared through evaluating their degradation efficiencies of methyl green dye. The co-doped sample exhibited a degradation efficiency of 92.6% for MG dye, as compared to 37.4% for undoped sample. Furthermore, after five cycles, the co-doped samples only showed a 2% reduction in the photocatalytic efficiency, indicating its potential for long-term reuse29.

A wide variety of synthetic methodologies for fabrication of spinel nanomaterials can be identified, including (SGA), hydrothermal30, solid-state, microemulsion, green synthesis, etc. Among these methodologies, the SGA process emerges as the most distinguished approach. This process confers a variety of advantages, such as cost-effective precursors, minimalistic equipment requirements, and low temperature synthesis. This method utilizes a self-propagating combustion reaction that significantly improved the efficacy of material production31. Utilizing the sol-gel process, the researchers have found that it enables better mixing of starting materials, leading to the enhanced chemical homogeneity and improved properties in the resulting materials32. In this approach, the characteristic of the resulting material depends on the factors like, starting precursor, pH and type of fuel used for starting the reaction. In this process the starting precursor generally consists of water-soluble salts like nitrates, and for the fuel the most prominent choice is the citric acid. Citric acid (C6H8O7) is widely used because it serves as both a chelating and capping agent. Citric acid initiates the exothermic reaction and serves as the fuel in the combination. Its play 2 important roles in the SGA: (1) it produces carboxylic groups to equally distribute ions, and (2) it acts as a fuel for self-combustion, leading in more effective discharge of volatile compounds. Although the sol-gel process is primarily used at laboratory scale for research purposes, some studies have also shown the wide scale potential of the SGA technoque. The reliability of this approach in producing highly crystalline material could help greatly in maintaining the quality of the produced material. Barlaf et al., (2021) discussed the utilization of sol-gel approach for preparing different types of material over different aspects and conditions33. In another study by Ma et al., (2015) the scalability of the sol-gel was discussed and its potential to be used for large scale production of nanomaterial was discussed. These study demonstrate that sol-gel approach could prove beneficial for large scale nanomaterials production34.

The motive of this paper is to prepare the Dy3+-substituted barium hexaferrites of composition, BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06) via SGA for the breakdown of the CR dye. The structural, magnetic, photocatalytic, and optical traits were carefully studied. The prepared nanoferrites were used as the photocatalyst to eliminate the toxic CR through a photocatalysis under the natural sunlight, aiming at wastewater treatment.

Experimental

Material used

SGA technique was employed to fabricate BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02–0.06) nano-ferrites utilizing AR graded (> 99%) chemicals like barium (Merck), ferric (SimSon), dysprosium nitrate (Alfa Aesar), and citric acid (C6H8O7, SimSon). For the gelation the ethylene glycol (from Rankem) was used and to maintained the pH the ammonia (from SimSon) solution was used. The Congo Red dye was obtained from Central Drug House in New Delhi.

Fabrication of BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02,0.04, and 0.06) nano-ferrites

The dysprosium-doped barium hexaferrite, BaDyxFe12−xO19 (where x = 0.02, 0.04, and 0.06), was made via the SGA methodology. Individual solutions containing stoichiometric amounts of C6H8O7, and metal nitrate, were prepared in 80 millilitres of distilled water. A magnetic stirring apparatus equipped with a heated plate was employed to agitate these solutions at a 40 °C till a homogeneous solution was attained. Then, the C6H8O7 solution was integrated into the nitrates solution and agitated at 50 °C. Thereafter, a dropwise addition of NH3 solution was conducted to achieve neutralization of the resultant solution. Following this, ethylene glycol was introduced as a gel precursor into the aforementioned solution. At 50 °C, the mixture was agitated until the evaporation causes the generation of a gel. The resultant material was subjected to heating at 100 °C on a hot plate to yield a blackish ash residue. This ash residue was then finely ground utilizing a mortar and pestle, followed by calcination for 5 h at 1150 °C within a muffle furnace. Ultimately, the calcined material was prepared for an analysis of its microstructural, magnetic, optical, and photocatalytic traits.

Figure 1 illustrates schematic representation delineating the fabrication process of BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02 to 0.06) hexaferrites. Herein, BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02), BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.04), and BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.06) are termed as BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3, respectively.

Characterization

XRD of Bruker D8 was utilized to explore the structural traits. For the optical analysis, FTIR (PerkinElmer), XPS (NEXSA Surface analysis by Thermo Scientific) and RAMAN (RAM HR evolution via Horiba) were utilized. FESEM (JSM IT 800- Jeol) was employed to examine morphology of ferrite nanoparticles. The UV-Visible-NIR spectrophotometer (LAMBDA 750) from USIC-BDU was used to determine the band gap of the samples. The materials surface analysis was investigated by BET surface analyser (Anton par). VSM (Microsense, USA) was utilized for the magnetic analysis.

Photocatalytic degradation study

The degradation ability of the fabricated BaDyxFe12−xO19 ferrite nanoparticles was tested using CR dye as the pollutant. Experiments were done under controlled conditions to see how well the ferrite nanoparticles degraded the dye35. These tests were performed out with different pH values between 1.5 and 9.5 to find the best pH for maximal breakdown. Different concentrations of ferrite nanoparticles, ranging from 15 mg to 75 mg, were evaluated in 0.1 L of a 10 milligram/liters CR solution. For 90 minutes, the sunlight was served as the source of illumination. Samples of the reaction mixture were taken every 15 minutes during the photocatalytic studies. During analysis, 3 mL of the supernatant were taken out at each phase. This was an essential step in measuring the degradation progression over time. UV-VIS analysis was applied to evaluate the CR dye absorption in these samples both before and after they were exposed to sunlight. By comparing the starting and end dye concentrations, these measurements were utilized to examine the photocatalytic productivity of hexaferrites36. The formula was utilized to calculate the dye degradation efficiency37:

Where \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{o}}\) represents the initial amount of the CR, and \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}\) is the amount of CR at a specific period.

Results and discussions

X-ray diffraction analysis

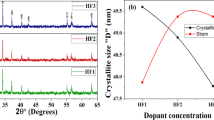

The XRD plot of prepared BaDyxFe12−xO19 exhibit in Fig. 2(a). The peaks were found at (110), (008), (112), (107), (114), (203), (205), (206), (217), (2011), and (220) for all samples. These peak positions provide the hexagonal phase of the fabricated material. The peaks detected in the patterns align well with (JCPDS 84–0757), indicating that the samples possess a P63/mmc symmetry38. No additional peaks were detected, demonstrating the purity of the attained phase. The M-type hexagonal ferrite exhibited high crystallinity, as evidenced by the sharp and well-defined Bragg peaks. Various structural parameters, including the unit cell volume (Vcell), lattice constants ‘a’ and ‘c,’ strain (ε), c/a ratio, X-ray density (dx), and crystallite size (D) were computed from XRD were shown in Table 1. The “D” of prepared samples was find using the most prominent (114) peak, applying the equation provided below:

Here K is the Scherrer constant, β is FWHM, λ wavelength, and θ is Bragg’s angle. The ε was also find by the formula:

The results indicated a consistent reduction in “D” from 39.66 to 25.05 nm as the concentration of Dy increased. This might be due to the larger ionic radii of Dy3+ related to Fe3+, causing to lattice distortion upon doping. The internal stress resulting from this distortion hinders the evolution of grains39. The microstrain is rises with doping. The Fig. 2(b) shows that with the increasing dopant content, the strain was found to be increasing which resulted in decreasing crystallite size, this implies the strain present is of compressive nature. A relative relation of strain with D is illustrated in Fig. 2(b).

The other structural parameter such as (a and c), (Vcell) and (dx) were find by Eqs. (3), (4) and (5):

In this context, d represents the interplanar spacing, while ‘a’ and ‘c’ denote the lattice constants, and (hkl) are the Miller indices. Here, n = 2, N is Avogadro’s number, and M stands for the molecular weight. As the concentration of Dy3+ increases, “a” stays nearly constant, whereas ‘c’ depicts an upward trend. This indicates that the c-axis experiences more significant changes compared to the a-axis, because of bigger ionic radii of Dy3+ related to Fe3+, as shown in Table 1. Additionally, the Vcell increases with Dy3+ doping. The “c/a” ratio, which lies from 3.93 to 3.94, confirms that the synthesized materials retain an M-type hexaferrite structure, as this ratio is below the threshold of 3.98.

To verify the purity of material, the Rietveld refinement was performed by FullProf software. The refinement findings, shown in Fig. 3, reveal a close match between (Y computed) and (Y observed), with a goodness-of-fit value less than 2 for all samples. This confirms the successful formation of a pure phase in all synthesized samples.

FESEM and grain size analysis

The morphology of the BaDyxFe12−xO19 hexaferrite was examined via FESEM. Figs. 4(a) and (c) show the FESEM pictures of BDF1 and BDF3 samples, correspondingly. The images reveal the hexagonal-like structure characteristic of Dy-doped barium hexaferrite. Agglomeration is noticed, which can be relevant to the magnetic behaviour of the BDF1 and BDF3 due to weak Van der Waals forces, contributing to the clustering of grains. While smaller grains are distinctly divided by well-defined boundaries, larger grains exhibit soft agglomeration due to interactions among the adjacent particles. The grains appear randomly scattered and tend to coalesce into agglomerates. The grain size for all the samples was computed by ImageJ software. For BDF1, the calculated average grain size is 126.98 nm, while for BDF3, it is 252.52 nm, as display in Figs. 4 (b) and (d). The difference in grain size observed in FESEM images as compared to the D size is because the grains are composed of multiple crystallites, making the grain size larger. Furthermore, the grain size increases with calcination, as the high temperature promotes grain growth.

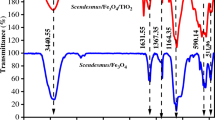

FTIR study

The material’s functional groups were identified via FTIR technique. Ferrites can be regarded as crystals with continuous bonding, where atoms are linked to their closest neighbours via, the covalent, ionic or van der waals interactions20. The spectra of Dy-substituted BaDyxFe12−xO19 were recorded in 500–4000 cm−1. The peaks in the 1000–400 cm−1 range indicate the existence of ferrite in the crystal. The specific bands for the different compositions, BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3, are represented in Fig. 5. The characteristic FTIR peaks of the synthesized material were identified at 537.59–542.13, 565.43–572.58, 892.89–895.32, and 1062.74–1066.03 cm−1 (v1, v2, v3, and v4). Table 2 shows the positions of the absorption bands based on the Dy doping levels. The absorption bands near 537.59–542.13 cm−1 (v1) and 565.43–572.58 cm−1 (v2) correspond to the bonds among metal and oxygen in tetrahedral sites. Meanwhile, the bands around 892.89–895.32 cm−1 (v3) and 1062.74–1066.03 cm−1 (v4) are ascribed to Ba–O and Dy–O–Dy vibrations40. The introduction of Dy3+ ions has been observed to cause a shift in the peaks toward higher wavenumbers. This change might be caused by the combination of smaller ions with greater ones, potentially resulting in an expansion of the lattice parameters in the samples. Consequently, it is inferred that these bands are related to the vibrations between the M-O ions at the voids within the structure of the synthesized nanomaterials.

Raman study

Raman spectroscopy offers insights into a material’s molecular vibrations, aiding in the analysis of its bonding and chemical structure. Figure 6 displays the Raman spectrum of BaDyxFe12−xO19 nanoferrites between 100 and 800 cm− 1. The spectra for the BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 reveal the existence of E1g, E2g, and A1g bands. Raman active modes were observed at 168–170, 179–181, 208–209, 331–334, 407–410, 461–466, 521–524, 612–614, and 680–683 cm−1, which closely match the known Raman modes of M-type hexaferrites. The modes at 168–170 and 179–181 cm−1 show the E1g symmetry due to the movement of spinel blocks, while the Raman active mode at 208–209, cm−1 is likely associated with M − O vibrations at octahedral (2a) sites39. The peaks at 331–334 and 407–410 cm−1 are associated with E2g and E1g symmetries, respectively, and are likely linked to the vibrations of octahedral 12k site. The peaks at 461–466, 521–524, and 612–614 cm−1 correspond to A1g symmetry, attributed to the vibrations at the octahedral (12k), octahedral (12k + 2a), and octahedral (4f2) sites41, . The mode at 680–683 cm− 1 shows the A1g symmetry at trigonal bipyramidal site at 2b site42,43,44. The shift in band position, as shown in Table 3, is attributed to the substitutions of Dy³⁺ ions at the octahedral sites42,45.

Magnetic study

The magnetic behaviour of the BaDyxFe12−xO19 hexaferrite are measured at ambient temperature via VSM with an applied magnetic field of ± 20 kOe. The M-H loop of the BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 specimens are demonstrated in Fig. 7(a). The hysteresis loop predicts the hard magnetic nature of fabricated specimens. By using the hysteresis loop different magnetic parameters are calculated such as coercivity (Hc), magnetization (Ms), and retentivity (Mr). Similarly, the magnetic moment (nB), and squareness ratio (Mr/Ms) are also computes by using the equations given below:

M is the molecular weight of the samples, and 5585 is the conversion factor obtained from Bohr magneton and Avogadro’s number. Fig. 7(b) depict the close view of the loop. According to the literature, the magnetic behaviour of the hexaferrite is influenced by the distribution of cations with in the crystal structure. In Table 4, a significant change in Ms was observed: as x increases from 0.02 to 0.04, Ms rises from 53.29 to 59.26 emu/g, but declines at x = 0.06. This variation in Ms is likely because of substitution of Dy3+ ions into the 4f2 and 4f1 crystallographic sites which tends to increase the Ms. This is because these sites typically involve spin-down moments. Conversely, in BDF3 sample, the Dy3+ ions occupy 12k, 2b, and 2a sites, which predominantly involve spin-up moments. This results in overall decline in magnetization. However, Mr increases from 28.91 to 32.12 emu/g when x rises from 0.02 to 0.04, before gradually decreasing to 24.95 emu/g at x = 0.06. Figure 7(c) illustrates how the concentrations of dysprosium affect the Hc, Ms, Mr, and nB of BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 nanohexaferrites.

The average saturation magnetization was calculated using the M vs. 1/H2 plot illustrated in Fig. 7(d). The coercivity is dependent on the factors like grain size, strain, and magnetic anisotropy. The material Hc is influenced by grain size, showing an inverse relation. The increase in grain size from 126.98 to 252.52 nm causes the values of Hc to fall from 2707.98 kOe at x = 0.02 to 3760.36 kOe at x = 0.04, followed by a slight decrease to 3562.08 kOe at x = 0.06. This suggests significant stability in the coercivity of the synthesized samples46. A single-domain magnetic structure is present in hexaferrite when the Mr/Ms value is greater than 0.5, whereas a multi-domain structure is suggested by an Mr/Ms value less than 0.5. The BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 samples in the current investigation had SR values of 0.54, 0.54, and 0.53, respectively.

XPS analysis

XPS is a surface-analysis technique that helps in determining the oxidation state and elemental composition of materials. A graph of intensity versus binding energy enables identification of the material’s elemental composition. Additionally, shifts in the binding energy of atoms with the same oxidation state can reveal variations in their local coordination environments. Figures 8(a) and 9(a) present the XPS spectra that were analyzed to understand the chemical structure of BDF1 and BDF3 samples. The spectra for the BDF1 sample (Fig. 8(a)) show peaks corresponding to Fe2p, Ba3d, Dy4d, C1s, and O1s, proving the existence of these elements in the samples. The BDF3 sample exhibits the similar peaks, indicating a comparable elemental composition. The binding energies recorded for the elements, as listed in Table 5, confirm the single-phase nature of BaDyxFe12−xO19 hexaferrite, free from impurities of other phases. Figsures 8(b) and 9(b) display the spectra of the Ba3d for both BDF1 and BDF3 samples. The peak of Ba3d is divided into two sub-peaks: Ba 3d3/2 and Ba 3d5/2, appearing at 779.47 eV and 794.78 eV, respectively is due to spin-orbital coupling. The spectra were collected within the 770 eV to 800 eV range, and the peaks confirming the presence of Ba2+ in the sample47. The Fe2p spectra for both BDF1 and BDF3 samples is depicted in Figs. 8(c) and 9(c). Due to the spin and orbital interaction, the peak is divided into 2-components: Fe 2p1/2 and Fe 2p3/2. The Fe 2p3/2 peak is divided into 2-distinct components, at 709.90 eV and 711.38 eV, which are ascribed to Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions, individually. Additionally, peak seems at 718.43 eV is the satellite. Also, the Fe 2p1/2 peak exhibits 2-separate components at 723.44 eV and 726.04 eV, corresponding to Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions. The satellite peak at 732.59 eV also observed.

Additionally, the highly defined oxygen 1s photoelectron peaks for both samples are shown in Figs. 8(d) and 9(d). The oxygen 1s peak is divided into 2- different peaks at 529.47 and 530.86 eV. The peak at 529.47 eV is related with metal oxide bonding, specifically O2− lattice oxygen, while peak at 530.86 eV indicates the existence of additional oxygen species and impurities at the material’s surface within the oxygen lattice.

The C1s peak, observed in both samples, suggests the presence of surface carbon due to environmental impurities. Figures. 8(e) and 9(e) display the XPS spectra of the C1s peak for BDF1 and BDF3. This peak is commonly utilized as a reference for determining binding energies. Additionally, a detailed examination of the Dy 4d peaks for both BDF1 and BDF3 samples is shown in Figs. 8(f) and 9(f). The Dy 4d peak is divided into two sub-peaks: Dy4d5/2 and Dy4d3/2. The peaks at approximately 155.2 eV and 152.64 eV assign to the 4d3/2 and 4d5/2 states, individually, signifying that Dy is present in the Dy3+ state48.

BET analysis

BET study is used to analyse the specific surface area of the prepared samples and to explain the physical adsorption of molecules on a solid surface21. The study is carried out via the N2 adsorption-desorption isotherm. The isothermal adsorption curves for the BDF1 and BDF3 samples are presented in Fig. 10. This graph indicates the existence of macropores and mesopores in the sample. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms for the sample suggests that, based on the IUPAC classification, it falls under group IV. The specific surface area was determined via isothermal adsorption model as follows:

Here (Po / P) represents the relative pressure, V is the adsorption volume, C is a constant, and Vm is volume. By plotting 1/[V(Po/P)−1] against Po/P using data at various relative pressures, a linear fit can be applied to the resulting curve49. The specific surface area was increased with Dy-doping. The specific surface area was found to be 1.069 m2/g for BDF1 and 1.466 m2/g for BDF3. The higher surface area enhances the photocatalysis because, as the surface to volume ratio increases the number of active sites also increases. This leads to greater number of interactions between the catalyst and the pollutants. Thus, the enhanced surface area aids in photocatalytic degradation.

Band gap analysis

Using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer, we studied how the BaDyxFe12−xO19 hexaferrites absorb the light within 200–800 nm. The absorbance plot in Fig. 11 showed that adding dysprosium ions to the BaFe12O19 structure significantly improved their photocatalytic abilities. However, when dysprosium ions are added, they create electron trap and defects that decrease recombination. This occurs as a result of the doped materials’ enhanced charge carrier separation and ability to absorb photogenerated electrons. This process reduces the Eg, making it easier to take in visible light and produce the electron-hole pairs required for photocatalysis50. The Eg of the nanoferrite were computed via Tauc plots51. This method uses the following equation:

where \(\:{\upnu\:}\) is the frequency of photon’s, h is Planck’s constant, \(\:{\upalpha\:}\:\)is the absorption coefficient, K is a proportionality constant, and the band gap energy is denoted by Eg. The exponent n varies based on transition, where (n = 1, 4) for the direct and indirect transitions. When dysprosium ions were added, the band gap decreased and which is good for photocatalytic applications. Specifically, BaDy0.06Fe11.94O19 with the highest concentration of dopants reduction in Eg to 1.99 eV. The other two samples, BaDy0.02Fe11.98O19 and BaDy0.04Fe11.96O19 had Eg of 2.16 eV and 2.12 eV, respectively show in Fig. 12. Doping reduces the band gap, which increases photocatalytic activity. A material with a narrower band gap absorbs photons with lower energy, such as visible light, which is widely present in the environment. This absorption leads to more efficient generation of electron-hole pairs that are vital for breaking down pollutants like CR dye52,53.

Photocatalytic study

In order to examine the efficiency of Dy-doped hexaferrite nanoparticles, the study investigated the breakdown of CR through photocatalysis in the sunlight. To remove organic contaminants as much as possible, parameters include pH and catalyst dose must be optimized53,54.

Impact of pH

The pH level significantly affects the elimination of the CR depicted in Fig. 13. Degradation is faster in acidic conditions (pH = 1.5) due to the ionization of dye molecules, which enhances interaction with the catalyst and promotes efficient breakdown. In alkaline conditions, degradation slows down because of repulsion among the dye particles and catalysts55,56,57.

Impact of catalyst dose

This investigation examined how different ferrite nanoparticles dosages affect the elimination of CR. Raising the catalyst does to 30 milligram enhanced dye degradation. Beyond this dosage, no significant improvement was observed, as shown in Fig. 14. Thus, 30 mg was found to be the optimal amount. Higher dosages increase the number of active sites and radicals and enhancing degradation. But, excessive catalyst amounts reduce light penetration and limiting further efficiency gains37,54.

Kinetics analysis

The study examines the degradation efficiency of CR by BaDyxFe12-xO19 nanoparticles doped with dysprosium ions. Three different ferrite nanoparticles were fabricated and tested for their degradation activity. The degradation percentages of dye achieved were 84.36%, 86.47%, and 89.29% for the BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 samples, respectively within 90 min. By a pseudo-1st-order kinetic model, the photodegradation kinetics were analysed, which revealed that the degradation rate varies with concentration of dye at any given time, depict in Fig. 15. The formula employed is36:

Where, \(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{a}\text{p}\text{p}}\)is the apparent pseudo-1st -order rate constant, \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{O}}\:\)is the initial amount and \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{t}}\) is the amount at time t of the CR. The model effectively describes the degradation of CR through these ferrite nanoparticles. The rate constants for the degradation were 0.016, 0.017, and 0.019 min− 1 for BDF1, BDF2, and BDF3 samples, respectively. Findings exhibited that the absorbance of the CR decreased significantly over time, indicating effective degradation. The maximum degradation rate was seen at 3.5 pH, with BDF3 sample showing the best performance. This sample reduced the dye concentration by up to 89.29% within 90 minutes of natural sunlight exposure. In contrast, lower degradation rates were observed at alkaline pH levels56,58,59. Additionally, increasing the ferrite nanoparticles dosage improved the degradation efficiency with 30 mg achieving the most significant reduction in dye concentration. These results confirm that doping BaFe12O19 with dysprosium ions enhances its photocatalytic activity, particularly under acidic pH conditions. The conclusions show the potential of BaDyxFe12−xO19 nanoferrite as the effective photocatalysts for the environmental pollutant degradation conditions. Many research studies have extensively documented photocatalytic degradation process36,54.

Many studies have extensively documented the photocatalytic degradation process36,54. During photocatalysis, the photocatalyst absorbs light energy with a frequency greater than its bandgap. This energy excites electrons from the valence band to the conduction band and creating positive holes in the valence band. Figure 16 illustrates this process. The positive holes react with water molecules to form hydroxyl radicals, while the excited electrons react with oxygen molecules to produce superoxide radicals. These reactive oxygen species, including both superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, then interact with the dye molecules, causing them to break down and lose their original structure60.

Table 6 presented data showing how incremental changes in Dy concentration led to variations in surface area, which affected the availability of active sites for photocatalytic reactions. It also illustrated how band gap alterations influenced the light absorption capacity and the efficiency of electron-hole pair generation. By correlating these changes with observed photocatalytic performance, the table provided a clear and concise overview of the relationship between Dy concentration and the material’s photocatalytic efficiency. This comprehensive analysis enhanced the understanding of the mechanisms driving the improvements in photocatalytic activity. Table 7 presents a comparative table of photocatalytic degradation of CR dyes.

Reusability study

Reusability of the catalysts plays a major role in determining its cost efficacy and reliability61.The reusability of BaDy0.02Fe11.98O19, BaCo0.04Fe11.96O19 and BaDy0.06Fe11.94O19 ferrite nanoparticles examined for five repeated cycles. The findings, depicted in Fig. 17, indicated no substantial decline in the CR dye breakdown efficiency. After 5 cycles, the reductions in efficiency were 5.77%, 6.05%, and 5.49% for the respective ferrite nanoparticles. The minor reduction in catalytic activity is because some loss of the catalyst while magnetic separation, washing, and drying. Despite this, the results show that BDF3 ferrite nanoparticles maintain high degradation efficiency. They demonstrate excellent reusability and stability over repeated cycles. This makes them highly suitable for long-term practical applications. Their consistent performance reduces the need for frequent replacement and enhancing their economic viability. These features establish BDF3 ferrite nanoparticles as an effective and sustainable option for environmental applications.

Conclusion

The Dy-doped BaDyxFe12−xO19 (x = 0.02–0.06) was synthesised by SGA approach. The XRD substantiates the presence of hexagonal phase with ‘D’ in the range of 25.05 to 39.66 nm. FESEM data indicate the hexagonal structure with a grain size of 126.98 and 252.52 nm for the BDF1 and BDF3 samples. As the Dy increases, the crystallite size decreases. FTIR spectra shows the band position at 537.59-542.13, 565.43-572.58, 892.89-895.32, and 1062.74-1066.03 cm− 1 represent the M-O stretching at the tetrahedral, presence of Ba-O, and presence of Dy-O-Dy band. The VSM was employed for the examination of the magnetic traits. The findings show that Ms, and Mr decrease as Dy-doping increases. Additionally, the surface area increases with Dy-doping are found to be 1.069 for BDF1 and 1.466 m2/g for BDF3 samples. The improved surface area enhance the photocatalysis due to the presence of more active sites. The photocatalytic efficiency was identified by observing the decomposition of CR in natural sunlight. A high CR degradation efficiency of 89.29% is demonstrated during 90 minutes of natural sunlight irradiation. The finding demonstrates a simple yet effective way for producing extremely efficient catalysts for dye degradation in treating wastewater.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed in this research are accessible from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ansari, S. A. et al. Emerging NiO–rGO nanohybrids for antibiotic pollutant degradation under visible-light irradiation. Surf. Interfaces. 40, 103078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfin.2023.103078 (2023).

Vidhya, N. et al. Hydrothermally synthesized TiO2-doped MnO2 nanocomposites for electrochemical and photocatalytic activity. Nano. 2450143. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793292024501431 (2024).

Vidhya, N. et al. Hydrothermally synthesized TiO2-Doped MnO2 nanocomposites for electrochemical and photocatalytic activity. Nano 2450143 https://doi.org/10.1142/S1793292024501431 (2024).

Shaterian, M., Enhessari, M., Rabbani, D., Asghari, M. & Salavati-Niasari, M. Synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of LaMnO3 nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 318, 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.03.087 (2014).

de Carvalho Marques, M., Mohamed, A. A. & Feitosa, P. Sustainable development goal 6 monitoring through statistical machine learning – Random forest method. Clean. Prod. Lett. 8, 100088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clpl.2024.100088 (2025).

Ali Ansari, S. et al. Novel furfural-complexed approach to synthesizing carbon-Doped ZnO with breakthrough photocatalytic efficacy. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.08.014 (2024).

Jasrotia, R. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of malachite green pollutant using novel dysprosium modified Zn–Mg photocatalysts for wastewater remediation. Ceram. Int. (2022).

Tkaczyk, A., Mitrowska, K. & Posyniak, A. Synthetic organic dyes as contaminants of the aquatic environment and their implications for ecosystems: A review, sci. Total Environ. 717, 137222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137222 (2020).

Jasrotia, R. et al. Photocatalytic dye degradation efficiency and reusability of Cu-substituted Zn-Mg spinel nanoferrites for wastewater remediation. J. Water Process. Eng. 48, 102865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2022.102865 (2022).

Jasrotia, R. et al. Robust and sustainable Mg1-xCexNiyFe2-yO4 magnetic nanophotocatalysts with improved photocatalytic performance towards photodegradation of crystal Violet and Rhodamine B pollutants. Chemosphere 294, 133706 (2022).

Ansari, S. A. Elemental semiconductor red Phosphorus/ZnO nanohybrids as high performance photocatalysts. Ceram. Int. 49, 17746–17752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.02.140 (2023).

Li, Q., Yue, Q. Y., Sun, H. J., Su, Y. & Gao, B. Y. A comparative study on the properties, mechanisms and process designs for the adsorption of non-ionic or anionic dyes onto cationic-polymer/bentonite. J. Environ. Manage. 91, 1601–1611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.001 (2010).

Patel, H. & Vashi, R. T. Removal of congo red dye from its aqueous solution using natural coagulants. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 16, 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscs.2010.12.003 (2012).

Jafarinejad, A., Salavati-Niasari, M., Monsef, R. & Bashiri, H. Flower-shaped magnetically recyclable ZnS/ZnIn2S4/Fe2O3 nanocomposites towards decolorization of colored pollutants. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 48, 3440–3455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.10.227 (2023).

Harja, M., Buema, G. & Bucur, D. Recent advances in removal of congo red dye by adsorption using an industrial waste. Sci. Rep. 12, 6087. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10093-3 (2022).

Karami, A. et al. Microwave synthesized erbium vanadate nano-photocatalyst: application for enhanced degradation of contaminated water. Int. J. Hydrog Energy. 48, 8499–8513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.12.017 (2023).

Ansari, S. A., Ansari, M. O. & Cho, M. H. Facile and scale up synthesis of red Phosphorus-Graphitic carbon nitride heterostructures for energy and environment applications. Sci. Rep. 6, 27713. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27713 (2016).

Salavati-Niasari, M., Salemi, P. & Davar, F. Oxidation of cyclohexene with tert-butylhydroperoxide and hydrogen peroxide catalysted by Cu(II), Ni(II), Co(II) and Mn(II) complexes of N,N′-bis-(α-methylsalicylidene)-2,2-dimethylpropane-1,3-diamine, supported on alumina. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 238, 215–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2005.05.026 (2005).

Umar, A., Ibrahim, A. A., Ansari, S. A. & Alhamami, M. A. M. Synthesis of zinc oxide sheets for improved photocatalytic performance. J. Nanoelectron Optoelectron. 19, 712–715. https://doi.org/10.1166/jno.2024.3629 (2024).

Salavati-Niasari, M. Host (nanocavity of zeolite-Y)–guest (tetraaza[14]annulene copper(II) complexes) nanocomposite materials: synthesis, characterization and liquid phase oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 245, 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2005.09.046 (2006).

Salavati-Niasari, M. Zeolite-encapsulation copper(II) complexes with 14-membered Hexaaza macrocycles: synthesis, characterization and catalytic activity. J. Mol. Catal. Chem. 217, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2004.02.022 (2004).

Ansari, S. A., Ansari, S. G., Foaud, H. & Cho, M. H. Facile and sustainable synthesis of carbon-doped ZnO nanostructures towards the superior visible light photocatalytic performance. New. J. Chem. 41, 9314–9320. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6NJ04070E (2017).

Khan, S., Noor, T., Iqbal, N. & Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic dye degradation from textile wastewater: A review. ACS Omega. 9, 21751–21767. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c00887 (2024).

Amiri, M., Pardakhti, A., Ahmadi-Zeidabadi, M., Akbari, A. & Salavati-Niasari, M. Magnetic nickel ferrite nanoparticles: green synthesis by Urtica and therapeutic effect of frequency magnetic field on creating cytotoxic response in neural cell lines. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 172, 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.08.049 (2018).

Jamshaid, M. et al. Engineering of Pr3 + doped M type PbFe12O19 hexaferrites to enhance photocatalytic degradation of nicotine. Chem. Phys. 581, 112264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemphys.2024.112264 (2024).

Jamshaid, M. et al. Facile synthesis of Yb3+-Zn2 + substituted M type hexaferrites: structural, electric and photocatalytic properties under visible light for methylene blue removal. Chem. Phys. Lett. 805, 139939 (2022).

Alvino, L. et al. Toxicity evaluation of barium ferrite nanoparticles in bacteria, yeast and nematode. Chemosphere 254, 126786 (2020).

Bibi, F. et al. Evaluation of structural, dielectric, magnetic and photocatalytic properties of Nd and Cu co-doped barium hexaferrite. Ceram. Int. 47, 30911–30921 (2021).

Bibi, F. et al. Evaluation of structural, dielectric, magnetic and photocatalytic properties of Nd and Cu co-doped barium hexaferrite. Ceram. Int. 47, 30911–30921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.274 (2021).

Salavati-Niasari, M., Loghman-Estarki, M. R. & Davar, F. Controllable synthesis of nanocrystalline cds with different morphologies by hydrothermal process in the presence of thioglycolic acid. Chem. Eng. J. 145, 346–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2008.08.040 (2008).

Mohammed, I. et al. Review on Y-type hexaferrite: synthesis, characterization and properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 16, 100416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100416 (2023).

Kurian, M. & Nair, D. S. Effect of Preparation conditions on nickel zinc ferrite nanoparticles: A comparison between sol–gel auto combustion and co-precipitation methods. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 20, S517–S522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jscs.2013.03.003 (2016).

Borlaf, M. & Moreno, R. Colloidal sol-gel: A powerful low-temperature aqueous synthesis route of nanosized powders and suspensions. Open. Ceram. 8, 100200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceram.2021.100200 (2021).

Ma, Q., Xu, Q., Tsai, C. L., Tietz, F. & Guillon, O. Sol–Gel method for Large-Scale production of nanopowders: Preparation of Li1.5Al0.5Ti1.5(PO4)3 as an example. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 99, 410–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/jace.13997 (2016).

Polley, K., Kundu, R. & Bera, J. Adsorption and sunlight-induced photocatalytic degradation of Methyl blue by BaFe 12 O 19 ferrite particles synthesised through co-precipitation method. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 103, 2038–2057. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2021.1887165 (2023).

Al-Farraj, E. S. & Abdelrahman, E. A. Efficient photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye using facilely synthesized and characterized MgAl 2 O 4 nanoparticles. ACS Omega. 9, 4870–4880. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.3c08485 (2024).

Riyanti, F., Nurhidayah, N., Purwaningrum, W., Yuliasari, N. & Hariani, P. L. MgFe2O4 magnetic catalyst for photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye in aqueous solution under visible light irradiation: 10.32526/ennrj/21/20230002, environ. Nat. Resour. J. 21, 322–332 (2023).

Sözeri, H., Mehmedi, Z., Kavas, H. & Baykal, A. Magnetic and microwave properties of BaFe12O19 substituted with magnetic, non-magnetic and dielectric ions. Ceram. Int. 41, 9602–9609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2015.04.022 (2015).

Kanwal, S. et al. Study of structural, spectral and dielectric properties of dy substituted Sr2Co2Fe12-xDyxO22 Y-type hexaferrites via sol-gel auto-combustion method for microwave absorption application. Mater. Chem. Phys. 322, 129558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2024.129558 (2024).

Mohammed, I., Mohammed, J., Carol, T. T. & Srivastava, T. A. K. Effect of Dy3+-Cu2 + doping on structural, magnetic and electromagnetic properties of Co2Y-type hexaferrite. Ceram. Int. 49, 16467–16476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.02.008 (2023).

Kumar, S. et al. Lattice strain mediated dielectric and magnetic properties in La doped barium hexaferrite. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 473, 312–319 (2019).

Mohammed, J. et al. Magnetic, Mössbauer and Raman spectroscopy of nanocrystalline Dy3+-Cr3 + substituted barium hexagonal ferrites. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 585, 412115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2020.412115 (2020).

Rana, K., Thakur, P., Tomar, M., Gupta, V. & Thakur, A. Investigation of Cobalt substituted M-type barium ferrite synthesized via co-precipitation method for radar absorbing material in Ku-band (12–18 GHz), Ceram. Int 44, 6370–6375 (2018).

Jasrotia, R. et al. Effect of rare Earth (Nd3+) metal doping on structural, morphological, optical and magnetic traits of Zn–Mg nano-ferrites. J. Rare Earths (2022).

Kadam: Structural, mechanical, dielectric properties… Google Scholar, (n.d.). https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Structural%2 C%20mechanical%2 C%20dielectric%20properties%20and%20magnetic%20interactions%20in%20Dy%203-substituted%20CoCuZn%20nanoferrites&publication_year=2020&author=R.%20Kadam (Accessed 19 Aug 2024).

Xue, Y. et al. Fabrication and magnetic performance of rare-earth dysprosium doped Ca-Mg hexaferrite nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 168, 112984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112984 (2024).

Suganya, M. et al. Electrochemical studies of novel X-Type barium hexaferrite nanoplatelets for supercapacitor applications. J. Supercond Nov Magn. 35, 915–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10948-021-06138-9 (2022).

Chanda, S., Maity, R., Saha, S., Dutta, A. & Sinha, T. P. Double perovskite nanostructured Dy2CoMnO6 an efficient visible-light photocatalysts: synthesis and characterization. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 99, 600–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-021-05605-y (2021).

Yang, Z. et al. Preparation of M-type barium ferrite submicron absorbing powder by one-step high-temperature ball milling and its particle structure regulation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 610, 172519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmmm.2024.172519 (2024).

Dhanda, N., Thakur, P. & Thakur, A. Green synthesis of cobalt ferrite: A study of structural and optical properties. Mater. Today Proc. 73, 237–240. (2023).

Mohsin, T. B., Islam, S. A., Tonni, T. T. & Rhaman, M. M. Analysis of conductivity and band-gap energy of bismuth ferrite nanoparticles as prospective photovoltaic material. Mater. Today Proc. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214785323004200 (Accessed 29 July 29 2024) (2023).

Fatima, G. et al. Mn-doped BaFe12O19 nanoparticles synthesis via micro-emulsion route: solar light-driven photo-catalytic degradation of CV, MG and RhB dyes and antibacterial activity. Mater. Res. Bull. 168, 112491 (2023).

Sudhakaran, A., Sudhakaran, A. & Sivasenthil, E. Investigating structure, elasticity, morphology, composition, and optical behavior of Al-doped BaFe12O19/CoZnFe2O4 hybrid composite. J. Mater. Res. 38, 1239–1253. https://doi.org/10.1557/s43578-022-00879-6 (2023).

Yadav, P., Dhariwal, N., Kumari, M., Kumar, V. & Thakur, O. P. Enhanced degradation of Congo-red dye by Cr3 + doped α-Fe2O3 nano-particles under sunlight and industrial wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 343, 140208 (2023).

Ali, N. et al. Photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye from aqueous environment using Cobalt ferrite nanostructures: development, characterization, and photocatalytic performance. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 231, 50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-020-4410-8 (2020).

Bessy, T. C. et al. Efficient antibacterial activities and photocatalytic degradation of congo red dye by CuxMg0.8 – xFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by combustion method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 34, 518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-023-09906-6 (2023).

Dinesh, A. et al. Sol–gel combustion synthesis and photocatalytic dye degradation studies of rare Earth element Ce substituted Mn–Zn ferrite nanoparticles. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 18, 5280–5289 (2022).

Boulahbel, H. et al. Enhanced photodegradation of congo red dye under sunlight irradiation by Pn NiFe2O4/TiO2 heterostructure. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 154, 110921 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Impact of Gd3 + doping on structural, electronic, magnetic, and photocatalytic properties of MnFe2O4 nanoferrites and application in dye-polluted wastewater remediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 30, 18820–18842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23420-y (2022).

ur Rahman, M. I. et al. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of a carbon quantum Dot/CaFe 2 O 4 hybrid nanocomposite for carcinogenic congo red dye degradation. RSC Adv. 13, 14461–14471 (2023).

Rashid, M. et al. Solar-light-driven and magnetically recoverable doped nano-ferrite: an ideal photocatalyst for water purification applications. Opt. Mater. 135, 113192 (2023).

Bahgat, M., Khedr, M. H. & Abdel-Moaty, S. A. Reduction kinetics, photocatalytic activity and magnetic properties of CoFe2 O4 /BaFe12 O19 core/shell nanoparticles. Mater. Technol. 22, 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355507X236641 (2007).

Behura, R., Sakthivel, R. & Das, N. Synthesis of Cobalt ferrite nanoparticles from waste iron ore tailings and spent lithium ion batteries for photo/sono-catalytic degradation of congo red. Powder Technol. 386, 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2021.03.066 (2021).

Kousar, T. et al. Facile synthesis of graphene anchored rare earth doped mixed metal ferrite nanorods: A potential candidate for Azo dye mineralization. J. Rare Earths. 42, 907–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jre.2023.07.002 (2024).

Kirankumar, V. S., Hardik, B. & Sumathi, S. Photocatalytic degradation of congo red using copper substituted Cobalt ferrite, IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 263, 022027. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/263/2/022027 (2017).

Hussain, M. et al. Influence of transition metal (Cu) and rare Earth metal (Dy) co-doping on spinel zinc ferrite (Cu0.1Dy0.08Zn0.9Fe1.92O4) for improved photocatalytic degradation of industrial effluents. J. Alloys Compd. 1010, 177242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2024.177242 (2025).

Ramakrishnan, R., Kalaivani, S., Amala Infant Joice, J. & Sivakumar, T. Photocatalytic activity of multielement doped TiO2 in the degradation of congo red. Appl. Surf. Sci. 258, 2515–2521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.10.085 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R391) at King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for the valuable support to this research. Guangxi Science and Technology Program (No. AA24010001, Research Project for Young and Middle-aged Teachers in Guangxi Universities (No. 2024KY0624).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. wrote the entire paper and conducted the data investigation; S.G., KS.N., J.M., and J.A., N.L., and S.M.A. given the resources and characterization; J.P. did review and editing; A.V. curated the data; X. Y. contributed with funding, B.L. contributed in the revision and R.J. supervised the full work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Himanshi, Makasana, J., Ganesan, S. et al. Insights into the enhanced photocatalytic degradation of congo red using advanced BaDyxFe12−xO19 catalytic hexamaterials. Sci Rep 15, 8978 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92145-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92145-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sol-gel fabricated Cu0.6Zn0.4-xCoxFe2O4 spinel ferrite based nano catalysts for green hydrogen generation

Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology (2025)

-

Magnetically Separable and Recyclable Fe3O4/HCl-Activated Kaolin/AgNPs Composite for Sustainable Photocatalytic Degradation of Congo Red

Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials (2025)