Abstract

This study evaluated the antioxidant and antibacterial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil synthesized using a green method. The analyses were conducted with three replications using a completely randomized methodology. The means were compared using Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of 5% using SPSS version 22 statistical software. In the microbial test, the antimicrobial property of zinc oxide nanoparticles with cumin essential oil was significantly higher than that of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil in both disc diffusion and microbroth dilution methods (p < 0.05). In addition, zinc oxide nanoparticles with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil had the most significant effect on Candida Albicans yeast, then on the gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, and finally on the gram-negative Escherichia coli bacteria. Zinc oxide nanoparticles combined with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil showed a better result than B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil in measuring the amount of total phenolic compounds (p < 0.05). In the test of particle size and dispersion index, there was a significant difference in the samples (p < 0.05). The lowest particle size and particle size dispersion index were related to the sample of zinc oxide nanoparticles with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given the growing concerns surrounding the side effects and disadvantages of chemical preservatives, medicinal plants, and natural compounds can be employed as alternatives for the preservation of food, the attainment of natural antiseptic and antimicrobial agents, and the prevention of the formation of harmful by-products. This practice is increasingly prevalent globally1. Due to the escalating resistance of bacteria to antibiotics and their side effects, the use of medicinal plants and plant essences has gained attention2. Currently, antibacterial substances serve a wide range of applications in medicine and industry3. Natural antimicrobial materials are harmless to humans and other organisms, do not pollute the environment, and are economically viable in terms of their organic and natural composition. Researchers believe that plant essences, or aromatic extracts, have significant potential as biological antibacterial agents and as replacements for chemical substances3.

Studies have demonstrated that the efficacy of certain natural plant essences can surpass that of synthetic materials in some instances. However, their major limitation is their high volatility and consequent instability. One of the best solutions to address this issue is the application of nanotechnology, which significantly enhances the stability and effectiveness of the desired compound4. Nanotechnology enables the fabrication and design of materials with novel properties and characteristics, with dimensions ranging from 1 to 100 nanometers5. Research has shown that nanotechnology can offer numerous advantages in antimicrobial materials, including reduced consumption of antimicrobials, increased efficiency, high environmental compatibility, and improved quality6.

Today, many nanoparticles are synthesized via chemical or physical methods. However, concerns have arisen due to the use of hazardous chemicals, their toxicity, and the resulting environmental damage7. There are various methods for nanoparticle production, including chemical, sonochemical, and electrochemical processes, microwave-assisted synthesis, and green synthesis8. The green synthesis method has gained a special place in research. It is a relatively new and largely unconventional method inspired by biological processes introduced to minimize or eliminate hazardous chemicals in nanoparticle production9. In this method, biological systems, which are safe and environmentally friendly, are used for nanoparticle synthesis10. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles offers more advantages over other physical processes as biological processes inspire it and are relatively inexpensive, eco-friendly, and sustainable. It also has pharmaceutical and biomedical applications and can be easily scaled up. Most importantly, these processes can be conducted at normal pressure and relatively low temperatures11. Due to their smaller size, zinc oxide nanoparticles easily traverse body tissues and the blood-brain barrier, reaching various organs such as the heart, brain, kidneys, and other organs via saliva blood flow. Zinc oxide nanoparticles are compatible with body tissues and have extensive medical applications, including effective drug delivery to target cells and tumor eradication12. Hosseini and Haji Aghajani (2018)13 examined the green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using apple fruit and investigated their antimicrobial effects. The results estimated the average particle size of zinc oxide at 10 nanometers. The nanoparticles synthesized using apple extract showed significant antimicrobial properties against Candida Albicans, with a halo diameter of 26 millimeters observed. Rajiv (2013)14 explored the use of cow chamomile plants for the synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles. The process involved mixing plant leaf extract with zinc nitrate and heating. The resulting zinc oxide nanoparticles were spherical and hexagonal, ranging in size from 22 to 90 nm. Studies on their antifungal activities confirmed their effectiveness against various fungal diseases. Moreover, in agriculture, these nanoparticles can selectively inhibit the growth of weeds and destroy harmful bacteria and fungi. Rafiei et al. (2018)15 assessed the green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Eucalyptus melliodora leaves. The results showed that the aqueous leaf extract could produce zinc oxide nanoparticles from zinc sulfate and indicated that these nanoparticles exhibited more potent antibacterial effects compared to both the aqueous E. melliodora extract and zinc sulfate itself.

Various plants can be studied in the synthesis of nanoparticles that have various therapeutic and medical properties and are used as herbal medicine. Nowadays, scientists have been led to use plants in nanoparticles, which can increase the effectiveness of these plants16.

Iranian black caraway, scientifically known as Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch., belongs to the celery family (Apiaceae) and falls under the flowering plant division of dicots, subclass Rosidae, and order Apiales. The Apiaceae family comprises 423 genera and 3,000 species17. Black caraway is an entirely glabrous herbaceous perennial plant with a bulbous, spherical, irregular root and a short subterranean stem. The stem, ranging from 40 to 60 cm in height, is grooved, erect, and branched with a straight, forked root.

Several chemical constituents found in B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch., such as cuminaldehyde, γ-terpinene-7-al, γ-terpinene, and p-cymene, have demonstrated significant pharmacological effects that include anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidant activities18.

Various methods are employed to extract the essential oil from black caraway, with steam distillation being the most common technique in the plant oil industry19.

The primary concentration of essential oil is found in the fruit, although other parts, such as the leaves, stems, roots, and flowers, also contain essential oils20. After the extraction of black caraway oil, the residue, containing 14–21% fat and 20% protein, serves as an appropriate feed for poultry19. In a study aimed at identifying the compounds present in black caraway oil, 16 components were detected, accounting for 99.36% of the oil’s composition. The study reported the highest percentages of oil from three compounds: gamma-terpinene (37.98%), cuminaldehyde (11.48%), and alpha-methyl-benzyl methanol (25.55%)20.

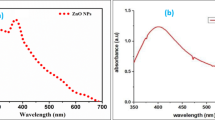

Asefian & Ghavam (2024)21 analyzed the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from the extract of the three plants Yarrow (A. wilhelmsii), Chamomile (M. chamomilla), and C. Turmeric (C. longa); moreover, it pledges to measure the antibacterial activity against some variants causing a skin rash. The results showed a color alteration from light yellow to dark brown and the formation of silver nanoparticles. The absorption peak with the wavelength of approximately 450 nm resulting from the Spectrophotometry analysis confirmed the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. The presence of strong and wide peaks in FTIR indicated the presence of OH groups. The SEM results showed that most synthesized nanoparticles had a spherical angular structure and their size was about 10 to 20 nm. The highest inhibition power was demonstrated by silver nanoparticles synthesized from the extract combined from all three species against Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis (23 mm) which had a performance far more powerful than the extract.

Ghavam (2023)22, investigated the antibacterial potential of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Nepeta sessilifolia Bunge and Salvia hydrangea DC. ex Benth. extracts from the natural habitats of Iran’s Rangelands. Based on the results of UV-Vis spectroscopy, silver nanoparticles synthesized from N. sessilifolia and S. hydrangea had distinct absorption peaks at wavelengths of 407 to 424 nm and 414 to 415 nm, respectively. The crystalline nature of these synthetic silver nanoparticles was confirmed by XRD. FESEM analysis showed that the size of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles from N. sessilifolia and S. hydrangea extracts were 10–50 nm and 10–80 nm, respectively, and were cubic. The results of diffusion in agar showed that the largest diameter of the growth inhibition zone belonging to the synthetic silver nanoparticles from both extracts of N. sessilifolia (~ 26.00 mm) and S. hydrangea (~ 23.50 mm) was against Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus. The most vigorous killing activity by synthetic silver nanoparticles from N. sessilifolia extract was against Klebsiella pneumoniae with a value of 250 µg/mL, two times stronger than rifampin.

The increasing use of chemical preservatives in food is one of the problems in the food industry today, and the use of such substances is directly related to the increasing prevalence of dangerous diseases such as cancer. Finding a way to eliminate chemical preservatives or at least reduce their consumption of food while maintaining its quality is of significant importance. Therefore, this study aimed to green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) using the essential oil of the Iranian B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. plant and investigating their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.

Materials and methods

Materials

The seeds of the Iranian B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. plant were obtained from Bojnord city and were approved by the botanical department of Jahad Keshavarzi Center of Natural Resources of North Khorasan province. All chemicals were purchased from Merck, Germany.

Methods

Extraction of Iranian B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil

The essential oil was extracted by distillation with water and using a clevenger machine23.

Percent of essential oil

The weighing method was used to determine the amount of essential oil. First, a clean, small glass container that had reached a constant weight in the oven was weighed. Then, B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil, which was separated from the Clevenger device, was poured into the containers. Then, the container containing essential oil was reweighed, and the amount of essential oil was obtained from the difference between the primary weight (weight of glass) and secondary weight (weight of glass and essential oil), which was expressed as a percentage of weight per hundred grams of dry matter20.

Dentification of compounds in Iranian B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil

A Coi

led chromatograph with a spectrometer (Thermoquest-Finnigan company, model (Trace) equipped with a 60 cm long DB column, 0.25 mm inner diameter, and 0.25 m thin layer thickness was used to analyze and identify essential oil compounds. Then, Wiley version 7 and NIST version 1.7 software were used to identify the compounds and search for valid libraries24.

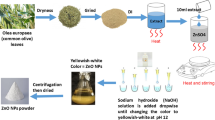

Preparation of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) along with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil

Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) were synthesized using a green synthesis approach to minimize environmental impact and avoid toxic chemicals. The process utilized eco-friendly precursors, including B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil, 6% aqueous zinc nitrate, 2 M sodium bicarbonate, and distilled water. First, 10 mL of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil, selected for its natural reducing and stabilizing properties, was mixed with zinc nitrate in a reaction flask. Gradually, 18 mL of 2 M sodium bicarbonate solution was added to adjust the pH and initiate the reduction process. The reaction mixture was stirred under a controlled temperature of 80 °C for 3 h, ensuring the completion of nanoparticle formation. The color change from light brown to cream indicated the successful synthesis of ZnONPs. Subsequently, the solution was filtered using a Buchner funnel and repeatedly washed with a 1:3 ethanol-distilled water mixture to remove impurities. The precipitate was initially dried at 80 °C for 20 h and then calcined at 500 °C for 3 h to enhance crystallinity and eliminate residual organic compounds, yielding pure white ZnONPs25.

Determination of particle size, particle size dispersion index, and zeta potential of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil

Particle size was measured based on the average volume diameter of the capsules, particle size dispersion index, and zeta potential based on the surface electric charge of the particle at room temperature with a dynamic light diffraction device (Malvern, ZEN3600, UK).

Electron microscope observation

The shape and size of zinc oxide containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil were investigated using a scanning electron microscope (LEO - Germany. Co-Model. VP1450) (SEM). For this purpose, the obtained white powder was mixed with 96% alcohol and sonicated for 15 min, and a drop of it was photographed by SEM after drying by placing a gold coating on it26.

Antimicrobial power of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil

The studied microorganisms, including microbial strains of Escherichia coli (PTCC 1399), Staphylococcus aureus (PTCC 1431), and Candida albicans (PTCC 5027) yeast, were obtained from the Medicinal Plants Research Institute of North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences. DMSO was obtained from Merck, Germany. In this research, Nutrient Broth (N.B) was used as the liquid culture medium for bacteria, and Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) was used for yeast.

Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles

Investigating the antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil was investigated using disk diffusion and microbroth dilution methods.

Disc diffusion method

The Kirby Bauer disk diffusion method was used to measure the antibacterial effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil27.

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) by microbroth Dilution method and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil

First, 0.2 g of the test nanoparticles were dissolved in 2 cc (0.5 cc DMSO and 1.5 cc Mueller Hinton broth), resulting in a concentration of 100 mg/mL. Subsequently, serial dilutions were performed in tubes, each containing 1 cc of Mueller Hinton broth, with the concentration of each subsequent tube being half that of the previous one (100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125, 1.562, 0.781, 0.390, 0.195 mg/mL). A total of 200 µl of these concentrations of nanoparticles (prepared in Mueller Hinton broth) were then transferred to the wells of a 96-well plate. A 0.5 McFarland standard microbial suspension was diluted tenfold to achieve an opacity equivalent to 1.07 × 107 bacteria, and 20 µl was added to each well. The 96-well plate was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After this period, 50 µl of Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) reagent was added to all the wells, and the plate was incubated again for 3 h. The first concentration at which no red color developed was designated as the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). To determine the Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC), 10 µl or a loop from all wells where no red color formed were transferred to plates containing Mueller Hinton agar. After 24 h of incubation at 25 °C, the first concentration at which no growth was observed was considered the MBC28.

Antioxidant activity

DPPH radical scavenging assay

To conduct the test, 50 µl of various concentrations (1, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mg/mL) were added to 5 mL of 0.004% DPPH solution in methanol. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the optical absorption of the samples was measured at 517 nm against a blank. The percentage of radical scavenging activity was calculated using Eq. 129.

AI%: percentage of free radical inhibition.

AControl: absorbance of the control solution at 517 nm.

ASample: absorbance of the sample solution at 517 nm.

Reducing power

The antioxidant activity of the samples at various concentrations (25, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 mg/mL) was assessed based on their Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) capability30. About 100 µl of the samples were mixed with 100 µl of the resulting solution, followed by the addition of 3 mL of FRAP reagent to evaluate the antioxidant activity. The absorbance of the solutions at 593 nm relative to the control (comprising 100 µl of distilled water with 3 mL of FRAP reagent) was measured. The iron reduction capability of the sample was calculated by placing the absorbance values in the equation related to the standard curve of divalent iron cation.

Determination of total phenolic content

The total amount of phenolic compounds in extracts was analyzed using the Folin-Ciocalteu method31. The Folin assay was performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in triplicate within a completely randomized design. Mean comparisons were performed using Duncan’s multiple range test at a 5% significance level with SPSS version 22. Additionally, charts were created using Excel 2013.

Results and discussion

The chemical analysis results of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil by GC/MS

The separation and identification of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil components were carried out using gas chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Fig. 1). Identifying the essential oil’s constituents was achieved through retention indices and mass spectra analysis, compared with standard mass spectra available in computerized libraries and reputable references (Tables 1 and 2). The average yield of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil across three replicates was approximately 2.81% ± 0.02, featuring a distinct amber-yellow color and fragrance. This study revealed that B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil contains 22 components. Among these, thymol (11.33%), para-cymene (17.17%), gamma-terpinene (15.14%), and cuminaldehyde (25.78%) were identified as key phenolic compounds. These components are known for their antibacterial and antioxidant properties, which likely contributed to the observed bioactivities32. In general, phenolic compounds potentially disturb the function of bacterial cell membranes which causes retardation of growth and multiplication of bacteria. Further phenolic compound involved in adhesion binding, protein and cell wall binding, enzyme inactivation, and intercalation into the cell wall and/or DNA during inactivation of pathogens33.

Azizi et al. (2009)34 examined the components present in wild and cultivated B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oils from the Khorasan region. The results indicated that 35 compounds were identified, accounting for approximately 95% of the essence. The wild type had a higher oil percentage than the cultivated type, although no significant differences in essence components between the two types were observed. In both types of essence, gamma-terpinene had the highest percentage, followed by cuminaldehyde, gamma-terpinene-7-al, and para-cymene35. Karim et al. (1977)35 also investigated the components of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil. Their findings demonstrated that the oil content in Pakistani B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil was 3.5–7.1%, with the main components being gamma-terpinene (19.8–28.9%), cuminaldehyde (14.8–22.5%), alpha-terpinene 7-al (4.8–7.2%), and gamma-terpinene 7-al (3.11–5.2%).

Oroojalian et al. (2009)36 studied the chemical constituents of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. and their antibacterial activity against S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, B. cereus, E. coli, and S. enteritidis. The results indicated that the principal identified components, in essence, were gamma-terpinene, cumin aldehyde, gamma-terpinene-7-al, and p-cymene. These compounds are known to disrupt bacterial cell membranes, leading to leakage of cellular contents and bacterial death37.

Gram-negative bacteria were more resistant to the essence. The highest antibacterial activity of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essence was against Bacillus cereus, followed by S. aureus and L. monocytogenes. Furthermore, the antibacterial effects of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. were attributed to high percentages of gamma-terpinene and cuminaldehyde36.

Takayuki et al. (2007)38 explored the antifungal effects of volatile compounds of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. on Fusarium oxysporum. The findings showed that B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essence comprises seven volatile compounds, namely gamma-terpinene, limonene, p-cymene, beta-pinene, alpha-pinene, cuminaldehyde, and myrcene, with cuminaldehyde being the primary antifungal component. Additionally, the antioxidant activity can be attributed to gamma-terpinene and p-cymene, which act as radical scavengers, preventing lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the significant role of phenolic compounds in essential oils39,40.

Souri et al. (2008)20 demonstrated that B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essence contains 16 compounds, which together constitute 99.36% of the total essence. In this study, the compounds with the highest percentages in the essence were gamma-terpinene (38.98%), cuminaldehyde (11.48%), and alpha-methyl-benzene methanol (2.55%).

Particle size, particle size distribution, and zeta potential

Particle size, particle size distribution, and zeta potential are presented in Table 3. As observed in Table 3, the largest and smallest particle sizes and distributions, respectively, pertain to the B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil sample and the zinc oxide nanoparticle sample containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil. The lower parameters in the zinc oxide nanoparticle sample containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil indicate a uniform distribution of compounds, thus demonstrating better stability. In contrast, higher parameters suggest a non-uniform distribution and a lack of solution homogeneity.

The addition of essential oils reduces particle size, likely due to the physicochemical properties, solubility, polarity, and molecule size of the active compounds. Active compounds in the essential oil, possessing charged groups, can establish hydrogen or ionic bonds with the polar head of phosphatidylcholine. Additionally, the hydrophobic nature of the active compound can embed within the phospholipid monolayer and bond with its hydrocarbon chain. In essence, the interaction between phosphatidylcholine and essential oil components influences particle size15. Particle size is an essential criterion for determining stability, encapsulation efficiency, and active compound release15 Smaller particle sizes are significant for several reasons, including higher bioavailability, increased colloidal stability, better solubility in aqueous environments, and more precise solutions with less turbidity41. Particle size distribution is a molecular parameter typically used to assess the uniform distribution of molecule sizes42 and is an essential predictor of the hydrodynamic volume and rheological properties of biopolymers in aqueous media, as well as for the homogeneity and molecular weight distribution of biopolymers43. The size of microcapsules for food applications should be less than 100 μm to prevent oral sensitization to food substances and to maintain product integrity, particle size distribution must also be limited44. Particle size distribution is a crucial index for determining the stability of nanocarriers. Values higher than 0.3 indicate a heterogeneous system, whereas values below 0.3 suggest a homogeneous and uniform system. Particle size distributions of the samples are less than 0.3, indicating a homogeneously produced system15. In Rafiee et al. (2017)15 regarding producing nanoliposomes containing polyphenolic compounds of pistachio, it was observed that the particle size distribution was less than 0.3, and they also reported the particles as uniform and homogeneous.

Oroojalian et al. (2009)36 investigated the chemical components of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil and their antibacterial activity against S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, B. cereus, E. coli, and S. enteritidis. The results indicated that the primary constituents identified in the essential oil were gamma-terpinene, cuminaldehyde, gamma-terpinene-7-al, and p-cymene. Gram-negative bacteria exhibited greater resistance to the essential oil. The most potent antibacterial activity of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil was observed against B. cereus, followed by S. aureus and Listeria monocytogenes. Additionally, the antibacterial effects of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. were attributed to high percentages of gamma-terpinene and cuminaldehyde. Takayuki et al. (2007)38 assessed the antifungal effects of volatile compounds in B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil against Fusarium oxysporum. The study revealed that B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil comprised seven volatile compounds, namely gamma-terpinene, limonene, p-cymene, beta-pinene, alpha-pinene, cuminaldehyde, and myrcene, with cuminaldehyde being the primary antifungal component38. Souri et al. (2008)20 demonstrated that B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil contains 16 components, accounting for 99.36% of the total essence. In this study, the highest percentages of the essence were related to three components: gamma-terpinene (38.98%), cuminaldehyde (11.48%), and alpha-methyl-benzene methanol (25.55%).

In a colloidal system, the potential difference between the immobile ionic layer and the mobile layer (diffuse layer) in the ionic atmosphere around charged particles is called zeta potential45. Zeta potential serves as the optimal indicator for determining the electrical status of particle surfaces; it reflects the accumulation of charge in the immobile layer and the intensity of opposite ion adsorption on the particle surface. A higher zeta potential enhances the electrostatic repulsive force, subsequently increasing the physical stability of the system46. Various factors, including pH, ionic strength, and the type and concentration of polysaccharide macromolecules, affect the surface charge and zeta potential47. As observed in Table 3, negative zeta potentials were noted in both samples. The presence of zeta potential on the surface of nanoparticles acts as an electrical barrier, creating a repulsive phenomenon that promotes physical stability and dispersion of particles48. Keivaninahr et al. (2019)49 reported zeta potentials of nanoliposomes containing cinnamon essence ranging from − 10.9 to -17.4 mv. They indicated that the negative charge on phosphatidylcholine increased with higher essence concentrations. Results pertaining to the zeta potential of nanoliposomes containing beta-carotene, produced using grape seed oil and squalene with surfactants Tween 20 and 80, also demonstrated excellent physical stability in both oil and surfactant types, with an average zeta potential below − 30 millivolts50.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of zinc oxide nanoparticles

The SEM image of zinc oxide nanoparticles is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen, the micrographs showed that the network formation occurred in the ZnO nanoparticles, and it was clearly shown that the aggregation took place.

Determining antimicrobial property

Investigating the antimicrobial effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil by disc method

In this study, the diameter of the growth inhibition zone in millimeters was determined for two bacterial strains and one yeast strain using zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil by the disk diffusion method (Table 4; Fig. 3).

As shown in Table 4, the antimicrobial activity of the zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil showed a significant increase compared to the essential oil alone (p < 0.05). The inhibition zones were as follows:

Gentamicin < C. albicans < S. aureus < E. coli.

S. aureus also showed a more significant antimicrobial effect and larger inhibition zone compared to E. coli when exposed to the zinc oxide nanoparticles, which can be attributed to the more excellent resistance of gram-negative bacteria’s cell walls to the penetration of foreign substances compared to gram-positive bacteria. Moreover, the diameters of the inhibition zones produced by the zinc oxide nanoparticles were significantly different from those of the positive control sample, gentamicin (p < 0.05).

Soleymani et al. (2010)51, in a study on the interaction effects and antibacterial activity of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil against several gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, reported that the disk diffusion results of this essential oil were better than those of the antibiotics oxacillin, ampicillin, erythromycin, and vancomycin on the E. coli strain used in the research. In addition, the MIC and MBC of this essential oil on E. coli were 0.0015 and 0.0031 mg/mL, respectively. Another finding was the synergistic effect of this essential oil on the antibiotic’s gentamicin and ampicillin against E. coli.

Examination of the antimicrobial power of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. Essential oil by microbroth Dilution method

The results comparing the effects of MIC and MBC on zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil are shown in Tables 5 and 6; Figs. 4 and 5.

As Table 5 indicates, significant differences were observed in the MIC effects on the studied bacteria (p < 0.05). Zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil had the most significant impact at a concentration of 3.125 mg/mL on C. albicans, followed by S. aureus at a concentration of 6.25 mg/mL and then on E. coli at a concentration of 12.5 mg/mL, which can be attributed to the resistance of gram-negative bacteria’s cell walls to the penetration of foreign substances compared to gram-positive bacteria. In the microbroth dilution method, zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil affected C. albicans at a concentration of 6.25 mg/mL, followed by S. aureus at a lower concentration of 12.5 mg/mL, and the bactericidal effect on E. coli was at a concentration of 25 mg/mL. The zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil showed a better bactericidal effect (MBC) compared to B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil alone (Table 6).

Based on the research, gram-positive bacteria exhibit greater sensitivity to the plant extract under study, aligning with previous research outcomes regarding both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria52. The heightened sensitivity of gram-positive bacteria to chemical substances, essential oils, and plant extracts is due to structural differences in their cell walls. Gram-positive bacteria possess a mucopeptide-rich cell wall, whereas gram-negative bacteria have only a thin mucopeptide layer and primarily consist of lipoprotein and lipopolysaccharide. Gram-negative bacteria are surrounded by an outer membrane that renders them more resistant to antibacterial agents52. The degradation of the cell wall leads to the leakage of cellular contents and, consequently, cell death. The efficacy of these compounds depends on the dosage and duration of exposure. Higher concentrations accelerate the destruction of microorganisms, thereby requiring a longer duration to achieve a similar antibacterial effect at lower doses52. The enhanced antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil compared to the essential oil alone can be attributed to synergistic and physicochemical mechanisms. ZnO-NPs generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, which disrupt microbial structures and functions. When combined with the essential oil’s bioactive components, such as cuminaldehyde and gamma-terpinene, this effect is amplified, targeting membrane integrity and metabolic pathways53. ZnO-NPs also enhance the penetration and bioavailability of the essential oil compounds, facilitating their interaction with microbial cells54. Additionally, ZnO-NPs interact electrostatically with negatively charged microbial membranes, while the essential oil’s hydrophobic compounds further destabilize the membrane, leading to leakage of intracellular contents. Together, these mechanisms, including increased ROS generation, cause oxidative stress and structural damage, resulting in improved antimicrobial efficacy55,56. Moradi et al. (2024)57 reported that Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Thymus daenensis Celak against wound causing microbes. The results indicated that synthesized silver nanoparticles demonstrated good inhibitory activity against baumannii (12.00 mm) and Gram-positive bacteria like S. epidermidis (22.00 mm) and S. aureus (21.67 mm). On the other hand, the findings indicated that the MIC value of synthesized silver nanoparticles against Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Serratia marcescens was 250 µg/mL, which was 6 times stronger than T. daenensis extract.

The ethanolic extract of Makhlaseh “in vitro” showed a considerable antibacterial effect against Enterobacter aerogenes, E. coli, Shigella flexneri as the gram-negative bacteria and Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes as the gram-positive bacteria. using Makhlaseh extracts as a natural antibacterial composite “in vitro” have significant antibacterial ability over the studied strains58 .

Guzman et al. (2012)59 showed that the smaller the size of the nanoparticles, the more pronounced their antibacterial properties due to differences in the minimum inhibitory concentration and minimum bactericidal concentration among various synthesized nanoparticles. The specific size and morphology of nanoparticles enable them to damage and breach the cytoplasmic membrane, affecting the cellular respiratory chain and the DNA and RNA, thereby exhibiting high antimicrobial activity59.

Soleymani et al. (2010)51 indicated that the MIC B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil against S. aureus and E. coli was 0.0125 and 0.0015 mg/mL, respectively, and the MBC was 0.025 and 0.0031 mg/mL. Oroojalian et al. (2010)36. also confirmed that Persian cumin and green cumin essential oils possess synergistic activity against Gram-positive bacteria and enhanced activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Moreover, gram-negative pathogens, including E. coli, exhibit more excellent resistance compared to other microorganisms. Additionally, the MIC of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil against S. aureus and E. coli was 0.75 and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively, indicating higher resistance in E. coli. Furthermore, they reported the MBC of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil against these two bacteria to be 0.75 and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively. The presence of some of the phytochemical components like saponins, tannins and phenolic compounds have been attributed to the antibacterial activity of the crude drugs observed. The presences of these bioactive components in the crude drugs have been linked to their activities against disease causing microorganisms and also offering the plants themselves protection against infection by pathogenic microorganisms60.

Determination of antioxidant activity

The amount of DPPH free radical trapping

Figure 6 DPPH free radical scavenging power of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil. *Means in a column followed by the different superscripts are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 by Duncan test.

The level of antioxidant activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil based on the level of DPPH free radical trapping is as follows:

BHT > Zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil > B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil.

The assessment of antioxidant activity through the DPPH free radical scavenging method is conducted in the absence of other free radicals, which leads to a color change in the medium. This change can be quantitatively measured with a spectrophotometer. The DPPH radical is stable, and the basis of this method is that the DPPH radical acts as an electron acceptor from a donating molecule, such as an antioxidant, resulting in the medium changing from purple to yellow. Consequently, the absorbance intensity at 517 nanometers decreases, allowing the antioxidant properties to be determined through spectrophotometric measurements61.

Reducing power

Figure 7 Effect of different concentrations of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing Bunium persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil and BHT on reducing power. *Means in a column followed by the different superscripts are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 by Duncan test.

As observed in Fig. 7, at all concentrations, zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil exhibit significantly greater reducing power than the essential oil alone (p < 0.05). However, this test indicated that both B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil and zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil possess antioxidant properties that facilitate the reduction of trivalent iron ions to divalent iron ions, potentially terminating radical chain reactions, thus demonstrating their antioxidant characteristics. The level of antioxidant activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil is described based on the reducing power method:

BHT > Zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil > B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil.

Haghirosadat et al. (2015)64 investigated the antioxidant effect of the essential oils of three plants, B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch., green cumin, and zenian, and concluded that all three have antioxidant properties.

Total phenolic content

Figure 8 Total phenol of zinc oxide nanoparticles. *Means in a column followed by the different superscripts are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05 by Duncan test.

The equation related to the standard curve of gallic acid to calculate the number of phenolic compounds is Y = 0.0038 X + 0.0044 (R2 = 0.9926). As shown in Fig. 8, the sample of zinc oxide nanoparticles containing B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil is significantly more than the sample of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil (P < 0.05). The useful effects of phenolic composition such as anticancer, antimutagenic and heart protective attributed, also the synthetic antioxidants being suspected to toxicity, have led to numerous studies for the extraction of these composition from natural resources65.

Conclusion

This study examined the antimicrobial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles in conjunction with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil. The results demonstrated that the antimicrobial efficacy of zinc oxide nanoparticles with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil was significantly greater than that of B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil alone in both the disk diffusion and microbroth dilution methods (p < 0.05). Additionally, the zinc oxide nanoparticles combined with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil had the most significant effect on C. albicans, followed by the gram-positive bacterium S. aureus, and finally on the gram-negative bacterium E. coli. The combination of zinc oxide nanoparticles with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil exhibited superior results compared to the essential oil alone in measuring the total phenolic content (p < 0.05). In the particle size and particle size distribution index tests, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05), with the smallest particle size and particle distribution index pertaining to the sample of zinc oxide nanoparticles combined with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil. Therefore, zinc oxide nanoparticles combined with B. persicum (Boiss.) B. Fedtsch. essential oil may serve as promising sources for the provision of natural resources with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Syed, I. & Sarkar, P. Ultrasonication-assisted formation and characterization of geraniol and carvacrolloaded emulsions for enhanced antimicrobial activity against food-borne pathogens. Chem. Pap. 1(1), 1–14 (2018).

Singha, R., Sonib, S. K., Patela, R. P. & Kalrab, A. Technology for improving essential oil yield of Ocimum Basilicum L. (sweet basil) by application of bioinoculant colonized seeds under organic field conditions. Ind. Crops Prod. 45, 335–342 (2013).

Frewer, L. J., Norde, W., Fischer, A. R. H. & Kampers, F. W. H. Nanotechnology in the Agri-Food sectorimplications for the future. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH Co. KGaA 75–87 (2011).

Rachmawati, H., Budiputra, D. K. & Mauludin, R. Curcumin nanoemulsion for transdermal application: Formulation and evaluation, drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 015(4), 560–566 (2015).

Govindaraju, K., Tamilselvan, S., Kiruthiga, V. & Singaravelu, G. Biogenic silver nanoparticles by Solanum torvum and their promising antimicrobial activity. J. Biopest. 3, 394–399 (2010).

Akhilesh, D., Bini, K. B. & Kamath, J. V. Review on span-60 based non-ionic surfactant vesicles (niosomes) as novel drug delivery. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Biomed. Sci. 3, 6–12 (2012).

Nadagouda, M. N., Hoag, G., Collins, J. & Varma, R. S. Green synthesis of Au nanostructures at room temperature using biodegradable plant surfactants. Cryst. Growth Des. 9, 4979–4983 (2009).

Dobrucka, R. & Długaszewska, J. Biosynthesis and antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles using Trifolium pratense flower extract. Saudi J. In: Biol. Sci. (2015).

Zhang, D. et al. Powder Part. J. 28, 116 (2010).

Gandhi, R. R., Suresh, J., Gowri, S. & Sundrarajan, M. Adv. Sci. Lett. 18, 234 (2012).

Zhou, H., Fan, T. & Zhang, D. Chem. Sus Chem. 4, 1344 (2011).

Nagajyothi, P. et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized using Polygala tenuifolia root extract. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 146, 10–17 (2015).

Hosseini, F. S. & Haji Aghajani, Z. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using Apple fruit and investigation its antimicrobial effects. Sci. Res. Appl. Biology. 29(18), 39–44 (2018).

Rajiv, P., Rajeshwari, S. & Venckatesh, R. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 112, 384 (2013).

Rafiee, B., Ghani, S., Sadeghi, D. & Ahsani, M. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using eucalyptus mellidora leaf extract and evaluation of its antimicrobial effects. J. Babol Univ. Med. Sci. 20(10), 28–35 (2018).

Manokari, M. & Shekhawat, M. S. Biogenesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using aqueous extracts of Hemidesmus indicus (L.) R. Br. Int. J. Res. Stud. Microbiol. Biotechnol. (IJRSMB). 1, 20–24 (2015).

Smith, J. & Brown, L. Chemical composition and therapeutic potential of Bunium persicum: A review. J. Med. Plants Stud. 10 (4), 123–135 (2022).

Bansal, S., Malhotra, E. V. & Joshi, P. B. Compounds and Biological Activities of Black Cumin (Elwendia persica (Boiss.) Pimenov & Kljuykov). Living reference work entry.1–18 (20203).

Zargari, A. Medicinal plants. Tehran Univ. Publications. 2, 509–515 (1996).

Souri, E., Amin, G., Farsam, H., & Barazandeh Tehrani, M. Screening of antioxidant activity and phenolic content of 24 medicinal plant extracts. Daru 16, 83–87 (2008).

Asefian, S. & Ghavam, M. Green and environmentally friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles with antibacterial properties from some medicinal plants. BMC Biotechnol. 24, 5 (2024).

Ghavam, M. Antibacterial potential of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Nepeta sessilifolia bunge and Salvia hydrangea DC. ex Benth. Extracts from the natural habitats of Iran’s rangelands. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 23, 299 (2023).

Shafei, M., Sharifan, A. & Aghazade Meshki, M. Composition of essential oil of Ziziphora clinopodioides and its antimicrobial activity on Kluyveromyces Marxianus. Food Technol. Nutr. 9(1), 101–108 (2021).

Sefidkan, F. & Pourmirzaei, A. & Darvish Zeidabadi, D. Investigating the effects of environmental factors on changes in the amount of black Bunium persicum essential oil in Kerman. Final report, Ministry of Jihad, Agriculture and Natural Resources of Kerman province. (2014).

Al-Garni, T., Abduh, A. Y., Al-Kahtani, N. & Aouissi, A. A. Synthesis of Zno nanoparticles by using Rosmarinus officinalis extract and their application for methylene bleu and crystal Violet dyes degradation under sunlight irradiation. 2021040038. (2021). https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202104.0038

Karimi, N., Behbahani, M., Dini, G. & Razmjou, A. Green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles using extract of edible and medicinal plant (Allium jesdianum). Razi J. Med. Sci. 25(9), 1–7 (2018).

Dar, J. S., Rauf Tak, I., Ganai, A., Dawood, M. & B. & Phytochemical studies on the extract and essential oils of Artemisia dracunculus L. (Tarragon). Afr. J. Plant. Sci. 8(1), 72–75 (2014).

Dinani, N. J., Asgary, A., Madani, H., Naderi, G. & Mahzoni, P. Hypo cholesterolemic and antiatherosclerotic effect of Artemisia aucheriin hyper cholesterolemic rabbits. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 23(3), 321–325 (2010).

Tsai, T. H., Chien, Y. C., Lee, C. W. & Tsai, P. J. In vitro antimicrobial activities against cariogenic Streptococci and their antioxidant capacities: A comparative study of green tea versus different herbs. Food Chem. 110(4), 859–864 (2008).

Benzie, I. F. F. & Strain, J. J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Methods Enzymol. 299, 15–27 (1999).

Mao, C-F. & Chen, J. C. Interchain association of locust bean gum in sucrose solutions: an interpretation based on thixotropic behavior. Food Hydrocoll. 20, 730–739 (2006).

Escobar, A., Perez, M., Romanelli, G. & Blustein, G. Thymol bioactivity: A review focusing on practical applications. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 1;13(12):9243-69 (2020).

Kauffmann, A. C. & Castro, V. S. Phenolic compounds in bacterial inactivation: a perspective from Brazil. Antibiotics 24(4), 645 (2023).

Azizi, A. & Davareenejad, G. H. Essential [boiss.]il content and constituents [boiss.]f black Zira ([boiss.]unium persicum [Boiss.] [boiss.]. Fedtsch.) from Iran during field cultivation (Domestication). J. Essent. Oil Res. 21 (2009).

Karim, A., Pervez, M. & Bhatty, M. K. Studies on the essential oils of the Pakistani species of the family umbelliferae, part 10. Bunium Persicum Boiss (1977).

Oroojalian, F., Kasra-Kermanshahi, R., Azizi, M. & Bassami, M. R. Phytochemical composition of the essential oils from three Apiaceae species and their antibacterial effects on food-borne pathogens. Food Chem. 120, 765–770 (2009).

Kovačević, Z. et al. Natural solutions to antimicrobial resistance: The role of essential oils in poultry meat preservation with focus on Gram-Negative Bacteria. Foods 3(23), 3905 (2024).

Takayuki, S., Mami, S., Azizi, M. & Yoshiharu, F. Antifungal effects of volatile compounds from black Zira (Bunium Persicum) and other spices and herbs. J. Chem. Ecol. 33, 2123–2132 (2007).

Bansal, S. et al. A comprehensive review of Bunium persicum: A valuable medicinal spice. Food Reviews Int. 17(2), 1184–1202 (2023).

Shahsavari, N., Barzegar, M., Sahari, M. A. & Naghdibadi, H. Antioxidant activity and chemical characterization of essential oil of Bunium persicum. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 63, 183–188 (2008).

Babazadeh, A., Ghanbarzadeh, B. & Hamishehkar, H. Phosphatidylcholine-rutin complex as a potential nanocarrier for food applications. J. Funct. Foods. 33, 134–141 (2017).

Kang, J. et al. New studies on gum Ghatti (Anogeissus latifolia) part I. Fractionation, chemical and physical characterization of the gum. Food Hydrocoll. 25, 1984–1990 (2011).

Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential – What they are and what they are not? J. Controlled Release. 235, 337–351 (2016).

Kaushik, R., Swami, N., Sihag, M. & Ray, A. Isolation and characterization of wheat gluten and its regeneration properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52(9), 5930–5937 (2015).

Deepa, V., Sridhar, R., Goparaju, A., Reddy, P. & Murthy, P. Nanoemulsified ethanolic extract of Pyllanthus Amarus scham & Thonn ameliorates ccl4 induced hepatotoxicity in Wistar rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 50, 785–794 (2012).

Khoshmanzar, M., Ghanbarzadeh, M., Hamishehkar, H., Soti-Khiabani, M. & Rezaei Makaram, R. Investigating factors affecting particle size, zeta potential and permanent rheological properties in a colloidal system containing sodium capacaragin-casetinate nanoparticles. JRIFST 4, 272–255 (2012).

Timilsena, Y., Adhikar, R., Kasapi, S. & Adhikar, B. Molecular and functional characteristics of purified gum from Australian Chia seeds. Carbohydr. Polym. 1–35 (2015).

Patil, G. B., Patil, N. D., Deshmukh, P. K., Patil, P. O. & Bari, S. B. Nanostructured lipid carriers as a potential vehicle for carvedilol delivery: application of factorial design approach. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 44(1), 12–19 (2016).

Keivaninahr, F. et al. Investigation of physicochemical properties of essential oil loaded nanoliposome for enrichment purposes. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 105, 282–289 (2019).

Lacatusu, I., Badea, N., Ovidiu, O., Bojin, D. & Meghea, A. Highly antioxidant carotene-lipid nanocarriers: synthesis and antibacterial activity. J. Nanopart. Res. 14(6), 1–16 (2012).

Soleymani, N., Sattari, M., Sepehriseresht, S., Daneshmandi, S. & Derakhshan Evaluation of reciprocal pharmaceutical effects and antibacterial activity of Bunium persicum essential oil against some gram positive and gram negative bacteria. Iran. J. Med. Microbiol. 4(1 and 2), 26–34 (2010).

Burt, S. Essential oils: their antibacterial properties and potential application in foods. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 94, 223–253 (2004). (2004).

Dobre, A. A. Antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles loaded with essential oils. Pharmaceutics 15, 2470 (2023).

Kalaba, M. H., El-Sherbiny, G. M., Ewais, E. A., Darwesh, O. M. & Moghannem, S. A. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) by Streptomyces baarnensis and its active metabolite (Ka): a promising combination against multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens and cytotoxicity. BMC microbiology. 9;24(1):254 (2024).

Solanki, R. et al. Nanomedicines as a cutting-edge solution to combat antimicrobial resistance. RSC Adv. 14(45), 33568–33586 (2024).

Dejene, B. K. Biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticle-functionalized fabrics for antibacterial and biocompatibility evaluations in medical applications: A critical review. Mater. Today Chem. 1, 42:102421 (2024).

Moradi, H., Ghavam, M. & Ghanbari, A. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Thymus Daenensis Celak against Wound Causing Microbes (Waste Biomass Value, 2024).

Alizadeh, B. & Imani Fooladi, A. A. Antibacterial activities, phytochemical analysis and chemical composition Makhlaseh extracts against the growth of some pathogenic strain causing poisoning and infection. Microb. Pathog. 114, 204–208 (2018).

Guzman, M., Dille, J. & Godet, S. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nano-particles against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomedicine 8, 37–45 (2012).

Pavithra, P. et al. Antibacterial activity of plants used in Indian herbal medicine. Int. J. Green. Pharm. 4(1), 22–29 (2010).

Dong, X., Hu, Y., Li, Y. & Zhou, Z. The maturity degree, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Eureka lemon [Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f.]: A negative correlation between total phenolic content, antioxidant capacity and soluble solid content. Sci. Hort. 243, 281–289 (2019).

Behbahani, B. A., Noshad, M. & Falah, F. Study of chemical structure, antimicrobial, cytotoxic and mechanism of action of Syzygiumaromaticum essential oil on foodborne pathogens. Potravinarstvo 13, 875 (2019).

Iqbal, S., Younas, U., Chan, K. W., Zia-Ul-Haq, M. & Ismail, M. Chemical composition of Artemisia annua L. leaves and antioxidant potential of extracts as a function of extraction solvents. Molecules 17, 6020–6032 (2012).

Haghiroalsadat, F., Azhdari, M., Oroojalian, F., Omidi, M. & Azimzadeh, M. The chemical assessment of seed essence of three native medicinal plants of Yazd Province (Bunium premium, Cuminum cyminum, Trachyspermum Copticum) and the comparison of their antioxidant properties. J. Shahid Sadoughi Univ. Med. Sci. 22(6), 1592–1603 (2015).

Alizadeh Behbahani, B., Shahidi, F., Yazdi, F. T., Mortazavi, S. A. & Mohebbi, M. Antioxidant activity and antimicrobial effect of Tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus) extract and chemical composition of its essential oil. J. Food Meas. Charact. 11, 847–863 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NA design and carried out the experiment, and FO and VH contributed in framing the article. EM supervised the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akhtari, N., Mahdian, E., Oroojalian, F. et al. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles green synthesized with Bunium persicum essential oil. Sci Rep 15, 12117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92224-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92224-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Phytogenic Synthesis of Chitosan-Doped Zinc Oxide Nano Composites Using Annona muricata Linn: Evaluation of Antibacterial, Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Activities

Biomedical Materials & Devices (2025)

-

Biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles from halophilic soil extracts exhibiting antioxidant and antibacterial activities

Discover Environment (2025)