Abstract

Post-bariatric hypoglycemia (PBH) is a metabolic complication of individuals with obesity who have undergone bariatric surgery, characterized by rapid glycemic excursions followed by hypoglycemic events usually occurring 1–3 h post-meal. Without an approved pharmacotherapy, dietary modifications are essential for managing PBH, with continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices emerging as crucial tools for capturing postprandial glucose responses that can guide intervention strategies to prevent PBH. The effectiveness of such interventions is based on the availability of rich datasets, containing both CGM and meal data. However, meal information is often incomplete, being its manual recording burdensome and prone to user-related errors. In response, we proposed a template match algorithm (TMA) for the retrospective identification of unreported meals using CGM data only. TMA relies on a similarity score calculated between a post-prandial glycemic curve template and the glycemic trace of interest. Our study demonstrates promising results: TMA correctly identifies 1237 out of 1340 meals, generating 208 false positives within a dataset of 20 PBH subjects monitored in free-living conditions for nearly 50 days, yielding a median F1-score of 0.90. The effectiveness of TMA enables its use to enhance data quality in long-term studies involving PBH patients, facilitating the development of new approaches to manage PBH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) is one of the most commonly practiced bariatric surgery procedure1,2 and a highly effective treatment for obesity with numerous demonstrated health benefits3,4. However, a large proportion of operated individuals experience postprandial hypoglycemia5, a condition often referred to as post-bariatric hypoglycemia (PBH). Usually, PBH occurs 1–3 h after food intake, especially when a high amount of carbohydrates is ingested. It is characterized by a post-prandial hypoglycemic episode, defined as a post-prandial glucose of < 54 mg/dL as suggested by the International Hypoglycemia Study Group6. PBH can manifest with autonomic (e.g., trembling, anxiety, palpitations, sweating) and neuroglycopenic symptoms (e.g., fatigue, concentration difficulties, confusion, vision changes)7, and can be dangerous in the short terms causing seizures, loss of consciousness and even death. Although PBH is well-documented in the scientific literature5,7,8,9, its exact pathophysiological mechanisms remain under active investigation.

Eating behavior, especially the timing and frequency of meals, is of great interest in this context, as post-surgery eating patterns are known to change significantly9. Moreover, dietary adjustments are a cornerstone in managing PBH, especially in the absence of approved pharmacotherapy. Their goal is to mitigate glycemic spikes and excessive insulin secretion, thereby reducing the frequency and severity of hypoglycemia episodes and improving safety for these individuals. However, accurate self-logging of food intake, which is key for clinicians to tune dietary adjustments, can be burdensome and prone to user-related errors, often resulting in incomplete and biased data, particularly in long-term studies. This difficulty highlights the need for reliable methods for determining meal timing, which can have significant applications in both clinical and research settings, to understand the glycemic response to meals and develop strategies for preventing and managing PBH.

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) sensors can be a crucial instrument in this context10. These minimally-invasive devices measure blood glucose concentration every 1–5 min for several days and provide real-time data to users via mobile applications, thus enabling continuous monitoring of glucose fluctuations. By offering detailed insights into glycemic patterns, CGM sensors can help identify key events, such as postprandial glucose responses. In individuals with PBH, meal-related hypoglycemia is typically preceded by rapid rises in glucose levels, leading to large glucose spikes7. This particular setting represents a suitable use case for template-matching algorithms (TMA), which are widely used in signal processing and have demonstrated strong performance in detecting specific patterns within complex datasets11,12,13, offering a potential solution for meal detection.

In this work we present a TMA designed to retrospectively identify unreported meals in CGM data from individuals with PBH, thus enabling the enrichment of datasets, and improving their completeness and reliability. Addressing the challenge of missing meal information could enable a deeper understanding of meal behavior, post-meal glucose responses, and hypoglycemia patterns, which plays a critical role for developing effective strategy, e.g., dietary ones, to improve PBH management. The algorithm, which relies on CGM data only, was developed, validated and tested on a dataset comprising 3,698 meals from 20 subjects diagnosed by PBH, recorded in free-living conditions. To evaluate the efficacy of our approach, we conducted a comparative analysis against a baseline naive approach based on glycemia information and the state-of-art algorithm for PBH meal detection integrated into the hypoglycemia prediction framework proposed by Laguna-Sanz14.

Results

The identification of unreported meals in the CGM traces has been performed by resorting to the template matching technique, a well-established methodology that measures similarity between two signals (the detailed strategy is described in section “The template matching procedure”). Briefly, TMA identifies portions of CGM data which are “similar enough” to a pre-established personalized template of the post-prandial glycemic response. Indeed, if the similarity measure is above a patient-specific threshold TH, to be tuned, a post-prandial period is detected, as well as the meal timing. Despite its long history of application, to the best of our knowledge, its specific utilization for meal detection from CGM data remains unexplored.

The data used for TMA development came from 20 PBH subjects monitored for almost 2 months in free-living conditions. Participants were instructed to annotate into an electronic diary the information regarding meals (i.e., the timing of the meal and whether it contained more or less than 30 grams of carbohydrates), from now on referred to as self-reported meals. More details about the dataset can be found in section “Dataset”.

Once identified the personalized TH (for details see section “Threshold optimization”), the performance of TMA has been assessed on a test set by measuring: i) true positives (TPs), indicating those meals identified by TMA which were actually reported by the subjects; ii) false positives (FPs), i.e., meals identified by TMA which were not meal events; iii) false negatives (FNs), indicating that TMA did not detect meals which were actually reported; and, when possible iv) true negatives (TNs), indicating that TMA did not detect meals when the subjects did not report them. Then, we calculated recall, precision and F1-score (see Eq. (1)) to evaluate the performance of TMA:

In the following paragraphs, we will walk the reader through the different scenarios we developed for providing a comprehensive assessment of the proposed algorithm. In the “ideal scenario”, we investigated the potentiality of TMA by assessing its ability to distinguish among regions of CGM data comprising meals vs regions without meals, manually selected prior the development of TMA. Once established its functionality in this setting, we move one step further by applying the proposed detection methodology on the entire CGM trace, in the so-called “real-world scenario”.

TMA performance in the ideal scenario

The first objective is to assess TMA ability to distinguish whether a meal is present or not within the CGM trace. To this aim, we partitioned CGM data in regions, namely region-of-interest (ROI). In particular, we considered: (1) meal ROIs, portions of CGM data where a meal is reported by the patient, and (2) no-meal ROIs, portions of CGM data where no meals have been ingested. For more details on how these regions have been extracted we refer the reader to section “Pre-processing of data”. The dataset resulted in a total of 2075 meal ROIs and 733 no-meal regions, which have been opportunely divided into train and test sets based on a 60:40 proportion (see Section “Train/Test split”).

In terms of classification performance, the algorithm considers one ROI at a time, and the similarity score between the template and the CGM trace within the ROI is calculated. In case of meal ROIs, if the score is above the personalized threshold, the meal is classified as TP, otherwise it is classified as FN. Regarding no-meal ROIs, if the score is above the threshold, the trace is classified as FP, otherwise it classified as TN.

The train set has been used for identifying the patient-specific THs, reported in Table 1 (see “ideal scenario”): the large variability of optimal TH among subjects (3.24 [2.64–5.00]\(\cdot 10^{3}\), median [25\(^{\rm th}\)–75\(^{\rm th}\) percentile]; minimum value: 0.98 \(\cdot 10^3\), maximum value 1.08 \(\cdot 10^4\)) further supports our choice to personalize TMA. Train set performance with optimal TH values results in a median F1-score of 0.99. This value, obtained in ideal scenario we designed, can be considered as the theoretical upper bound performance that can be achieved by TMA, thus proving that TMA stands as a suitable approach for the identification of unreported meals.

After TH optimization, TMA performance has been evaluated on the test set. The results are shown in Table 1 (see “ideal scenario”) in terms of median [25\(^{\rm th}\)–75\(^{\rm th}\) percentile] for recall, precision, and F1-score, and as total number for TN. The results in the ideal scenario, where the algorithm is fed only with CGM regions containing self-reported meals (meal ROIs) and no-meal periods (no-meal ROIs), are promising: TMA detected 691 self-reported meals out of 714, ensuring a median recall of 0.97 within the subjects. It correctly classified 232 no-meal regions out of the total as TN, misclassifying only 8 no-meal regions as FP and resulting in a median precision of 1.00. The median F1-score, derived from these values, is 0.98.

Besides the detection of postprandial period, TMA allowed to identify the timing of meal intake (for details see section “Meal timing estimation”). To this end, we evaluated the time difference between the time of meal reported by the patient and the time of meal estimated by TMA. Approximately, the time estimation error is about 5 min, meaning that TMA is also able to accurately identify the timing of meal intake.

TMA performance in real-world scenario

Based on the encouraging results achieved in the ideal scenario, we moved a step further. Unlike the previous analysis, which evaluated only meal ROIs and no-meal ROIs, in the real-world scenario TMA is applied to the entire glycemic trace, thus mirroring the practical use of the algorithm. In daily-life setting, missing CGM values, spurious oscillations of glucose levels due to time-varying drift in sensor accuracy15, compression artifacts, and consecutive meals within a short time interval can lead to false and erroneous detections, challenging the robustness of the developed approach. Additionally, as previously stated, a critical issue which negatively influences the training and a fair assessment of TMA is the presence of unreported meals. To this end, the original data logged by the patients were supplemented with accurate meal information manually reported via visual inspection by two clinicians and an expert in the field, all of whom were blinded to the TMA development and assessment process. This process identified 1623 unreported meals, bringing the total to 3698 events when combined with the patient-reported meals. The identified portions of data are referred to as unreported-meal ROIs and are described in detail in section “Pre-processing of data”.

As in the previous scenario, the evaluation considers one meal at a time and calculates the similarity score between the template and the CGM trace. If the score is above the personalized threshold, the meal is classified as TP; otherwise it is classified as FN. Since the whole trace is considered in this case, any peak in the similarity score that does not correspond to a meal is classified as FP.

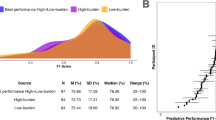

The train set has been newly used to identify patient-specific TH values, which are reported in Table 1 (see “real-world scenario”). The new optimized threshold results in a larger median value compared to the previous optimized one (5.29\(\cdot 10^{3}\) vs 3.24\(\cdot 10^{3}\) for real-world and ideal scenarios, respectively). This can be partially expected as real data poses several issues besides unreported meals, such as glucose fluctuation due to, e.g., exercise, stress and hormones, and sensor noise. Since TH is optimized maximizing F1-score, as explained in section “Threshold optimization”, a higher value of TH can be explained as the effort of the optimization process in balancing TPs and FPs, trying to account for a low number of FPs. Train set performance results in a F1-score of 0.89, which now accounts for 2358 meal ROIs. The training procedure can also be visualized in Figure 1: each line corresponds to the training phase of a specific subject, while the red dots identify the best performance (in the train set) obtained in terms of F1-score. The operative points satisfactorily approach the ideal one, in the upper-right corner (red star), for which both precision and recall are equal to one. Of note, in two out of 20 patients, TMA yielded lower F1-scores in the training set due to a 31% average reduction in precision, primarily driven by increased false positives likely caused by noisier CGM data.

As regards test set performance, now calculated on 1340 meals, Table 1 (see “real-world scenario”) displays them in terms of median [25th–75th percentile] of recall, precision and F1-score: in the real-world scenario TMA results in a median F1-score of 0.90, detecting 1237 meals out of 1340, counting 0.78 FPs/day. Median recall and precision result in 0.92 and 0.87, respectively.

TMA comparison vs state-of-art strategies

Once obtained the final version of personalized TMA, we compared its performance with the state-of-art methodologies described in section “Comparators”: a naive approach based on glycemic information (nGly) and an algorithm already published in the literature (LS). Table 2 shows the results in terms of median [25th–75th percentile] of recall, precision and F1-score.

Compared to other methodologies, TMA results in higher recall and precision: median recall of 0.92 vs 0.67 and 0.69; and median precision of 0.87 vs 0.81 and 0.79 for TMA, nGly and LS, respectively. The naive algorithm and the state-of-art exhibit comparable performances, both yielding a median F1-score of 0.71. However, they generate 236 and 254 FP, and 471 and 463 FN, respectively, calculated overall the 20 subjects. In contrast, TMA enhances their F1-score by +0.19, resulting in 208 FP and 103 FN.

Discussion

An effective management of post-bariatric hypoglycemia requires a comprehensive understanding of disease’s key aspects, such as meal behavior, post-meal glucose responses, and hypoglycemia patterns, which depends on the availability of high-quality data containing that relevant information. In this study, we introduce a personalized template match-based algorithm for offline identification of unreported meals in patients who underwent RYGB surgery. TMA can be employed as a valuable pre-processing step to enhance data quality in long-term studies, particularly when patients struggle to manually record each meal, and can also be used to enrich existing datasets lacking meal information. By improving the completeness and reliability of these datasets, TMA can facilitate the development of tailored strategies for PBH management.

Initially, we evaluated the ability of TMA to distinguish whether or not a meal is present in a selected portion of the CGM trace (“ideal scenario”). Our findings confirm the suitability of the template matching technique for this specific task, achieving a median F1-score of 0.98 in the test set. Specifically, TMA accurately classified 97% of self-reported meals, while only misclassifying 0.03% of no-meal ROIs. In the “real-world scenario”, a deterioration of TMA performance is expected, as real data poses several challenges. Here, to simulate the application of TMA in a practical scenario, we evaluated the algorithm considering the entire CGM trace (the test set comprised 266 days, i.e., 76,608 CGM samples). Under these conditions, TMA successfully detected 545 out of 590 unreported meals, demonstrating its ability to discern meals among glucose fluctuations not necessarily associated with a meal. TMA also ensures to correctly detect 92% of the total meals generating only 0.78 FP/day. Comparing TMA with other available methodologies, TMA outperformed state-of-art methodologies in terms of both correct identification of unreported meals and generation of false positives, achieving better recall, precision and F1-score than nGly and LS. For an accurate and objective estimation of meal timing, we evaluated it solely in the ideal-scenario, where meal ingestion time was self-reported by the individual. As a matter of fact, the real-world scenario also includes unreported meals, manually labeled via visual inspection by clinicians and expert users, whose meal timing is unknown. Focusing only on meals reported by the users in the ideal-scenario, TMA provides precise meal timing estimation, with a mean time error of approximately 5 min. Achieving such a small error was expected given the offline application of TMA.

Due to the large intra-individual variability characterizing PBH population, a key element of TMA is personalization. It is realized by taking into account two key elements: the post-prandial response template and the meal detection threshold TH that is used to detect a meal. TMA personalization is essential to tailor the specific subject and to achieve accurate performances within the described framework. However, to create the individualized template and to tune the personalized TH some pilot data are necessary. At least two weeks of monitored glucose data should be used to retrieve the detection threshold TH, and the patient must report five meals to create their specific template. Although the overall results demonstrate that the proposed TMA outperforms all state-of-art comparators, preliminary data availability may impose some burden on clinical trial design and existing dataset pre-processing. Therefore, this issue must be kept in mind. Nonetheless, as reported in “Supplementary material”, the less demanding version of TMA which uses a population template and population-tuned TH, also achieved promising results compared to the state-of-art. Specifically, this version showed median F1-score, recall and precision of 0.86, 0.90, and 0.86, respectively (vs, 0.71, 0.67, and 0.81 of nGly and 0.71, 0.69, and 0.79 of LS). This version can thus be used at first glance, while recording data from which, subsequently, retrieve the information necessary to customize the algorithm.

To further enhance TMA, the personalized template could be adapted over time using a run-to-run policy by integrating self-reported meals and recent subject-specific dynamics. Additionally, behavioral factors, such as usual meal times and composition, could improve the differentiation between meals. These refinements can be helpful to better identify unreported meal which are temporally close, addressing a critical aspect of this TMA version. These will be the objective of future investigations, along with the expansion of the current dataset and the creation of a user-friendly graphic interface that integrates TMA, aiming to facilitate accessibility for doctors and engineers, which will easily have access to suggestion for unreported meal positions. Nevertheless, the simplicity of the algorithm proposed in this work is essential to underscore its intrinsic potential-a potential that is supported by the presented results. Another possible application of TMA can be its adaptation to individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D), where unreported meal detection remains a significant challenge, contingent on adequate methodology adjustments. While real-time use in T1D insulin therapy would require further development, exploring its offline application to this population’s data will be part of our future work.

As a conclusive remark, the pre-processing steps detailed in our study, which involved both clinicians and experts in the field, as explained in section “Pre-processing of data”, were necessary for providing a fair assessment of the proposed methodology but are not required for a real-world application of TMA, which is designed to be used directly on CGM traces.

Methods

The template matching procedure

The template matching technique is extensively utilized in both image and signal processing to localize and identify patterns by means of a similarity score between a template and a target signal11,12,13. Typically, the similarity measure between two signals, represented as x of length N and t of length M (\(M < N\)), is assessed using cross-correlation. In the case of finite discrete real signals, cross-correlation is defined as:

Figure 2 represented an illustrative example of how the template matching algorithm works. Figure 2a shows an example of post-prandial period, used as template of the shape we want to detect, i.e., t. Figure 2b shows the functioning of TMA: the top panel shows the sensor glucose trace (x in Eq. 2), and the post-prandial periods we want to detect through TMA (target events) highlighted by the red dashed area. The bottom panel shows the similarity measure computed between x and t. The red dotted line indicates the threshold (TH) above which the algorithm identifies an event (post-prandial periods). In the top panel, the red dots indicates where TMA suggest to locate the detected meal (see section “Meal timing estimation”). As explained in the following paragraph, the identification of TH requires an optimization procedure.

(a) Example of post-prandial curve template. (b) Example of template matching algorithm for meal detection functioning. In the top panel, the glucose trace and the target events, i.e., the post-prandial curves, highlighted with the red area, are reported, along with the estimated meal time (red dots). In the bottom panel, the similarity score between the glucose time-series and the template is displayed. As explained in section “Evaluation”, when a local maximum in the cross-correlation exceeds a threshold (bottom panel, red dotted line), a post-prandial curve is detected, and the meal timing is retrieved as detailed in section “Meal timing estimation”.

The computation of the cross-correlation can be viewed as the output of a linear time-invariant moving-average filter applied on the glucose trace. More specifically, the order of the filter is denoted by M and the coefficients \(b_j, j=1,2,...M\) are the samples of the template: \(b_1\) corresponds to the last sample \(t_M\), \(b_2\) corresponds to the second last \(t_{M-1}\), until \(b_M\) which correspond to template’s first sample \(t_1.\)

Following a comparison process with TH, the filter outputs y(n), i.e., the cross-correlation between the signals, identifies the presence or absence of the desired waveform. Therefore, a crucial step of this methodology is the identification of a suitable template.

Personalized template

Considering the large variability of individuals’ responses to food intake, the design of a personalized template of post-prandial glucose profile is preferable. Defining a robust and representative template is a challenging task16. To this aim, we selected for each patient, five post-meal periods such that: (1) post-prandial glucose dynamics are aligned with the physiological expectation that, after a meal, glucose level increase and is followed by a sharp decrease to low glucose concentrations, (2) there are no missing data on CGM readings, (3) the are no artifacts due to mechanical sensor compression, and iv) each period starts from the euglycemic range. The five post-prandial curves were aligned based on their peak values and then averaged to simulate a typical response to carbohydrate intake, as shown in Fig. 3a: as a result, the template (black dotted line) is computed where a sample from each curve is available. In Fig. 3b, the personalized templates retrieved for each subjects are reported.

Threshold optimization

Once the template has been identified, the cross-correlation between the template and the sensor glucose trace can be computed. Post-prandial periods are detected in the sensor glucose trace if the cross-correlation between the two signals (the template and the glucose trace) exceeds a certain threshold value, denoted as TH.

To select a suitable TH for each subject, we conducted a grid-search approach, exploring a range from the minimum to the maximum value of the cross-correlation of each specific subject, and choosing the value of TH that maximize the F1-score on the train set. The optimized TH is then used on the test set.

Meal timing estimation

After the detection of a post-prandial period, the TMA allowed us to provide an estimate of the timing of meal intake. As a matter of fact, the local maximum of the similarity score is achieved when the template is overlapping the postprandial period. This means that the meal ingestion has occurred \(\tau\) min before the peak of the similarity score, with \(\tau\) equals to half of the size of the proposed template.

Evaluation

TMA performance was evaluated as the ability to detect meals events. In particular, this process unfolds as follow. For each meal, self-reported ones for the ideal scenario and a combination of self-reported and unreported ones for the real-world scenario, the algorithm considers the time window from 15 min before the meal to 2 h after the meal. This specific post-prandial window has been accurately chosen, consistently with the literature7, to address potential errors in the reported meal timing while ensuring the complete inclusion of the post-prandial curve. The subsequent step includes searching for an eligible peak, defined as a local maximum in the cross-correlation within the defined window and above TH. For each meal region, we count:

-

a TP if an eligible peak is present, indicating a match between the detected meal and the actual meal reported in the data;

-

a FN if a meal had been reported but no eligible peak is present, thus not detected by TMA.

In the ideal scenario, TN and FP are calculated within the no-meal regions. For each of them, we count:

-

a FP if at least one eligible peak is present in the region, accounting for a false meal detection by TMA;

-

a TN otherwise.

In the real-world scenario, where the entire trace was considered, FP were counted for each peak in cross-correlation above TH when the subject did not report a meal. From TP, FP and FN, we calculated the aggregated metrics of recall, precision and F1-score, already introduced in Eq. (1).

Of note, as highlighted in Fig. 2, TMA necessitates of a burn-in phase to well-calculate the cross-correlation. Indeed, this signal is characterized to an initial transitional phase where its values lack reliability, as they are computed without considering the entire template (the reader can imagine the template gradually sliding over the target signal from the left). This clearly occurs at the beginning of the signal, but the same problem occurs when the signal is interrupted by some missing values: more details on how we dealt with this issue are reported in “Pre-processing of data”.

Dataset and pre-processing

Dataset

The dataset used in the present work derives from an observational study (NCT05212207) conducted at the University Hospital of Bern (Switzerland). The study included individuals aged 18 years or older (age: 52 [43.0–61.8] years, 76.5% female, post-surgery BMI: 24.7 [24.7–27.7] kg/m2; median [25\(^{th}\)–75\(^{th}\) percentile]) who had undergone RYGB and had confirmed PBH. Key exclusion criteria included other causes of hypoglycemia, pregnancy or lactation. Full details on the data collection are reported in17. The study was approved was approved by the Ethics Committee Bern (Kantonale Ethikkommission für die Forschung Bern, 3010-Bern, Switzerland, Project ID 2021-02086) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the principles of Good Clinical Practice, and the local legal requirements. Participants provided written informed consent prior to study-related procedures.

Participants were instructed to wear and calibrate a blinded Dexcom G6 sensor (Dexcom, Inc., San Diego, CA) while keeping an electronic diary with information such as meals, sleep, and activity for 50 days, recorded in free-living conditions.

Specifically regarding meals, participants were asked to log the time of ingestion and whether the meal contained more or less than 30 grams of carbohydrates. For TMA development, only sensor glucose data and meal timing information were utilized.

Pre-processing of data

To test algorithm’s performance in the ideal scenario, which includes segments with self-reported meals and portions without meals, thus under controlled conditions, some pre-processing steps were necessary.

First, we maximized the portions of data uninterrupted by missing values. For this, short sequences of missing CGM data (<30 min) were interpolated, preserving the natural glucose behavior; and remaining signal sequences without a minimum amount of glucose data were discarded, which could potentially lead to the exclusion of some meals. This was necessary to maximize the portion of cross-correlation calculated considering the overlap of the entire template, as mentioned previously in section “Evaluation”.

In Table 3 the amount of glucose data, the number of self-reported meals and the number of missing values regions before and after the first step of pre-processing are reported as median [25th–75th percentile].

For the second step, we selected the first 20 subjects with at least 14 monitoring days. This duration was deemed reasonable as it allowed for dataset division into train and test sets, crucial for optimizing the parameter used by TMA and testing its performance.

Due to the intrinsic uncertainty of patient-logged entries, which can lead to missing information, timing inaccuracies, and incorrect logs, the establishment of a reliable ground truth is necessary for an accurate assessment of TMA. For this reason, clinicians and experts in the field manually labelled by visual inspection three distinct regions within the glucose traces: (1) ROIs for self-reported meal, capturing the post-prandial period of a patient self-reported meal (mean duration: 200 min); (2) ROIs for unreported meal, capturing the post-prandial period of an unreported meal (mean duration: 194 min); and (3) ROIs for no-meal, representing sections of glucose data without any self-reported or unreported meals (mean duration: 315 min). Each ROI for unreported meals had also its supposed time of ingestion flagged for reference.

An example of the three ROIs is graphically shown in Fig. 4.

This resulted in data from 20 subjects with 41.5 [28.4–45.0] of monitoring days median [25th–75th percentile] and a total of 2075 self-reported meals (84 [47–145] per subject), 1623 flagged unreported-meals (71 [44–129]) and 733 no-meal regions (36 [23–43]) for the development and testing of the TMA. Among the 3698 total meals, the glucose nadir was observed, on average, 122 min after the meal, with a mean value of 72 mg/dL. A total of 586 meals were followed by PBH, with a nadir observed at 120 min after the meal, aligning with the literature7, and an average glucose level of 45 mg/dL.

Meal ROI and no-meal ROI were used for the evaluation of the ideal scenario, whereas the combination of meals from meal ROIs and unreported meal ROIs was utilized for the evaluation of the real-world scenario.

When calculating the cross-correlation between the glucose trace and the template, zero-phase digital filtering was applied to the CGM data to reduce noise while ensuring minimal phase distortion and preserving the natural characteristics of the signal.

Train/Test split

To determine the optimal personalized TH for meal detection, we partitioned the dataset into train and test sets.

Initially, for the analysis under ideal conditions, we divided each glucose trace in a 60:40 proportion based on the number of self-reported meals, thus ensuring a balanced number of meals in train and test sets. It was ensured that the split occurred at the first missing value available, preserving the integrity of long sequences of glucose data. As we expanded our considerations to include labelled unreported meals, thus in the real-world scenario, we re-calibrated the train/test split. This time, it followed a 60:40 ratio calculated from the combined count of self-reported and unreported meals, flagged during the pre-processing second step.

In Table 4 some details of the splits are reported.

Comparators

We compared the performance of the TMA to two other meal detection algorithms. We selected a naive approach (nGly) based on glycemic values and glucose rate of change (ROC), i.e., glycemia first derivative calculated over the previous 15 min. Meals are detected when sensor glucose values exceeds 150 mg/dL with positive ROC. nGly is characterized by a shut-off period of 40 min when a meal is detected. In addition, we implemented the sole approach for meal detection in the PBH population (that is integrated into an hypoglyceamia prediction framework) and was proposed by Laguna-Sanz et al.14 (LS). The algorithm detects a meal if the last three samples of ROC (calculated using a four-sample moving-average filter exceeds 1 mg/dL/min.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT05250271, NCT05212207) are available upon reasonable request to their principal investigator: Lia Bally, Prof. Dr. med. et phil., Department of Diabetes, Endocrinology, Nutritional Medicine and Metabolism, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern (Lia.Bally@insel.ch). The code used for reproducing the results of this manuscript is available at https://github.com/elisapellizzari/TMA.

References

Colquitt, J. L., Pickett, K., Loveman, E. & Frampton, G. K. Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2014).

Angrisani, L. et al. Ifso worldwide survey 2016: primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes. Surg. 28, 3783–3794 (2018).

Wolfe, B. M., Kvach, E. & Eckel, R. H. Treatment of obesity: weight loss and bariatric surgery. Circ. Res. 118, 1844–1855 (2016).

Schauer, P. R. et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 641–651 (2017).

Ilesanmi, I. et al. Roux-en-y gastric bypass increases glycemic variability and time in hypoglycemia in patients with obesity and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 44, 614–617 (2021).

I. H. S. Group. Glucose concentrations of less than 3.0 mmol/l (54 mg/dl) should be reported in clinical trials: a joint position statement of the american diabetes association and the europian association for the study of diabetes. Diabetrs Care 40, 155–157 (2017).

Salehi, M., Vella, A., McLaughlin, T. & Patti, M.-E. Hypoglycemia after gastric bypass surgery: current concepts and controversies. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabol. 103, 2815–2826 (2018).

Svane, M. S. et al. Postprandial nutrient handling and gastrointestinal hormone secretion after roux-en-y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy. Gastroenterology 156, 1627–1641 (2019).

Suhl, E., Anderson-Haynes, S.-E., Mulla, C. & Patti, M.-E. Medical nutrition therapy for post-bariatric hypoglycemia: practical insights. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 13, 888–896 (2017).

Cummings, C. et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in patients with post-bariatric hypoglycemia reduces hypoglycemia and glycemic variability. Diabetes Obesity Metabolism (2023).

Brunelli, R. & Poggiot, T. Template matching: matched spatial filters and beyond. Pattern Recogn. 30, 751–768 (1997).

Hashemi, N. S., Aghdam, R. B., Ghiasi, A. S. B. & Fatemi, P. Template matching advances and applications in image analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.07231 (2016).

Niennattrakul, V., Srisai, D. & Ratanamahatana, C. A. Shape-based template matching for time series data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 26, 1–8 (2012).

Laguna-Sanz, A. J. et al. Design and clinical evaluation of a novel low-glucose prediction algorithm with mini-dose stable glucagon delivery in post-bariatric hypoglycemia. Diabetes Technol. Therapeut. 20, 127–139 (2018).

Facchinetti, A. et al. Modeling the glucose sensor error. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 61, 620–629 (2013).

Centracchio, J., Parlato, S., Esposito, D., Bifulco, P. & Andreozzi, E. Ecg-free heartbeat detection in seismocardiography signals via template matching. Sensors 23, 4684 (2023).

Tripyla, A. et al. Relationship between symptom perception and postprandial glycemic profiles in patients with postbariatric hypoglycemia after roux-en-y gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes Care 46, 1792–1798 (2023).

Funding

The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B. and D.H. conceived the studies, recruited participants and collected the data; E.P., F.P., and A.F. designed the case of study; E.P. and F.P. developed the algorithm; E.P. implemented the algorithm; E.P., F.P., G.C., S.F, D.H., and A.F. analysed the results; E.P. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; E.P., F.P., G.C., E.I., S.F., D.H., L.B., and A.F. have critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript. L.B. and A.F. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pellizzari, E., Prendin, F., Cappon, G. et al. Automatic identification of unreported meals from continuous glucose monitoring data in individuals after bariatric surgery using a template matching algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 7797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92275-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92275-3